Sam Quinones's Blog, page 7

December 6, 2016

Jury Duty and Ray

Late last week, I was put on a jury to decide whether a man with schizophrenia ought to remain in a mental hospital under a conservatorship, one consequence of which is that he would be forced to take his medication.

I was an alternate, meaning my function was to hear the evidence and be there should one of the jurors be unable to continue. It was a short, though slow-moving trial. I fought drowsiness through parts of it, mostly because the courtroom was so quiet and trials often get bogged down in minutiae.

Listening to three psychiatrists talk about his mental illness was interesting. What struck me were the terms used to describe the symptoms: disorganized thought, delusions of grandeur, inability to perceive reality or form sentences that make sense. “Poverty of thought” was another that intrigued me. So was “lack of insight.” Seems like these terms could describe us all from time to time.

On Monday, the man I’ll call Ray took the witness stand. He didn’t want this conservatorship. In quiet tones and flat affect, he told us he would take his meds if he were released, that he knew he was schizophrenic. He had a shaved head, a Fu Manchu and tiny tattoos of crosses on his temples near his eyes.

We had seen him shambling in and out of the courtroom each day with attendants from the mental hospital, arms not moving by his side, mouth always slightly open under the mustache. We hadn’t yet heard him speak. Now he was talking to us in terms that seemed to make sense.

Then without any change of tone or expression, he began telling us that he was also a NASA engineer. That, though he was 27, he had received a PhD from El Camino Community College in the 1980s. That he was an astronaut, a pilot who flew for Continental Airlines, which his father owned. That he had millions of dollars in the bank, owned an apartment complex, had a twin brother, that police chloroformed him and shaved his eyebrows.

He went on for about 10 minutes, a forlorn figure, lost in the tangle of his mind.

At one point, the bailiff walked over with some tissue for a woman on the jury who was crying.

The prosecutor, not given to expression, kept on asking questions of Ray with an agonized look on his face, wanting us to see the person and the reason we were there – that seeing real mental illness was necessary to do our job.

“This is a sad case,” he said.

I imagined Ray trying to take care of his basic needs – bathing, food. I couldn’t picture it. I imagined him on the street in some confrontation with police who would naturally see him as a menace, unaware of his illness. This collision would end badly — one that, even as he died, he wouldn’t understand. That was easier to see.

As a society, I believe, we have abdicated our responsibility for the mentally ill. Preferring not to pay taxes to do what we should, washing our hands of them. A few blocks from the courthouse are encampments of homeless people, some probably as ill and deluded as Ray. We have left it to police on the streets to be our frontline mental health professionals. Then we complain that officers have performed incorrectly when that combustible situation predictably goes wrong. That’s our fault.

My fellow dozen jurors, after a reasonable amount of debate in a room by themselves, determined that Ray qualified for the conservatorship, keeping him in the hospital, which is what I would have done.

Then, with the judge’s thanks, we all turned in our jurors badges and dispersed into Los Angeles.

The post Jury Duty and Ray appeared first on .

December 2, 2016

One Mother

On Facebook, I read the simple account – I’ve broken it out into four lines – from a mother from Kentucky. I’ve posted her story, and then the comments that followed:

I lost my son in August,

and my Daughter day after thanksgiving

the only two children I had

oh it’s so hard.

COMMENTS

I have no words. I’m sorry just doesn’t seem to be enough. May

you find the strength you need to carry you through.

I’m so sorry, I lost 2 sons in three years.if i can help you add me as a friend.hugs

may God give you the strength to survive the loss of both of your children. Hugs and prayers to you mom

may God give you the strength to survive the loss of both of your children. Hugs and prayers to you mom

So very sorry for your loss prayers and hugs to sister momma I have lost two sons and no words to heal your pain

We lost my oldest nephew Joe on 7/5/16, it is terrible and sad and I’m so glad for this group. You are not alone sister

November 24, 2016

Many Thanks

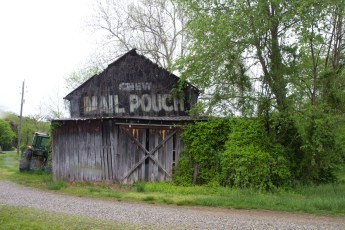

I’m a reporter with an earring, from L.A., a Berkeley grad who doesn’t go to church. In the last year, I’ve spent a lot of time in small American towns, meeting people from fairly traditional, church-going places in the Midwest.

On paper, on social media, or on 24-hour cable news, we would seem to have little to share.

Yet in these places, meeting these people, I’m struck by how much we have in common. This may sound trite, but it is true. The commonality is there if you want to look for it. Not that hard to find when you look someone in the eye.

At each place, I’ve had the great privilege of talking with folks about their lives, their jobs. I’ve been struck by the intensity of feeling of the people with whom I’ve spoken, hugging folks I didn’t know. I remember a paramedic telling me of saving overdosing addicts, and of a chamber of commerce president telling me how many people couldn’t pass drug screens. I remember a grandfather in Portsmouth who wouldn’t let my hand go as he told me how he was raising his granddaughter, that his daughter was in prison. Many had lost children, and many others were cautious yet happy that their children were doing well now.

It is a humbling and powerful thing to be brought so quickly into the intimate lives of strangers, and I hope more than anything that I’ve been up to the responsibility.

Today, I want to say how thankful I am to the people I’ve met in those places – Peoria, Van Wert, Scottsburg, Logan, South Shore, Marysville, Portsmouth, Marion, Huntington, Albuquerque, Medford, Zanesville, Knoxville, Covington, Chillicothe – for their warmth and hospitality and, above all, their willingness to share a bit of their stories with a guy from out of town.

These are not towns typically on most authors’ book tour itinerary, and I feel so lucky that I was able to get there.

I’ve met folks at conferences of associations I didn’t know existed two years ago: Kentucky Association of Counties, National Association of Community Health Centers, Indiana Hospital Association, Ohio Association of School Nurses, Illinois Rural Hospital Association, Oregon Narcotics Officers Association, West Virginia Medical Association, National Association of Medicaid Directors, and the Iowa Association of County Medical Examiners, among them.

Meeting people at these conferences has been a real light of the last year as well. The Kentucky Association of Counties a couple weeks ago was an amazing event, as the state has 120 counties for four million people. So it was really like a small-town convention. Folks with strong Kentucky accents and me with my earring – yet I felt so welcome, and their reception to what I had to say was overwhelming.

I’m thankful for my family, who has been so important in all that’s happened. They were able to accompany me on a trip to Chillicothe, Ohio, which we’ll never forget.

I’m thankful that my wife and I are in good health, happy with our lives. My daughter is a cheerful, intelligent girl, healthy and polite to others. My wife and I are thankful for that.

It’s been a good, full year and I hope it was for you, too.

Happy Thanksgiving.

The post Many Thanks appeared first on .

November 21, 2016

Donald Trump & Opiates in America

This fall I traveled a lot to Heartland areas to talk about a book I’d written about opiate addiction in America, and this provided me with a close view of the rise of Donald Trump’s candidacy.

The areas where I spoke were particularly hard hit by narcotic abuse — rural Michigan, southern Indiana, West Virginia, Kentucky, and several towns in rural Ohio.

The prevalence of Trump/Pence yard signs in these areas, particularly by mid-October, was stunning. As I traveled, it seemed palpable, this connection between Trump support and opiate addiction.

Not that there weren’t other reasons people supported him. A suffocating political correctness on the left is another factor in his appeal, I believe.

But nothing darkens your view of your present and future prospects quite as thoroughly as addiction to opiates (pills or heroin) in your family, on your street, or in your town. With opiates comes a fatalism and negativity that clouds a town or a family’s feeling about its world, even as unemployment falls and the economy improves.

In theory, addiction knows no race. In reality, though, our national opiate scourge is almost entirely white. Very few non-whites are among the newly addicted to prescription pain pills, then heroin. In three years of book research, I met one.

Though this scourge has affected every region of the country, it is felt most intensely in rural, suburban – Heartland – areas of America where Donald Trump did extraordinarily well.

Some of these areas did not fully rebound from the Great Recession of 2007 (southern Ohio). Others fared much better (North Carolina). A common denominator, I think political scientists will find, is that in these areas since the last presidential election the incidence of opiate addiction spread, grew deadlier, more public, and went from pain pills to heroin. In southern Ohio, where heroin has hit like pestilence, particularly Appalachia, Trump trounced his opponent in counties that Mitt Romney barely won four years earlier – though unemployment in many of these counties is at its lowest level in years, sometimes decades.

Shannon Monnat, a rural sociologist and demographer at Penn State I talked with, found strong correlations between suicides and fatal drug overdoses in counties where Trump’s increase was larger that the share of the vote compared to Romney’s four years earlier – this in six Rust Belt states, another half-dozen state in New England and all or part of the eight states comprising Appalachia.

One place I spoke was Hocking County (pop. 28,000). Hocking has lost coal mining jobs in recent years, though its unemployment rate dropped this fall to 4.5 percent, the lowest in more than 20 years. (It hit 14 percent in 2010.) But Hocking has also grown far more aware of its pill/heroin problem. Overdose deaths are up. Its drug court is among the first in the state to use Vivitrol, the opiate blocker. Trump earned 66 percent of the vote in the county Romney carried with 49 percent four years ago.

Opiate addiction – to pain pills or heroin — is the closest thing to enslavement that we have in America today. It is brain-changing, relentless, and unmercifully hard to kick. Children who complain at the slightest household chore while sober will, once addicted, march like zombies through the snow for miles, endure any hardship or humiliation, for more dope.

In many of these regions, folks were unprepared for it and, what’s more, believed they had done nothing to deserve it. Kids with no criminal record, star athletes, pastors’, cops’, and mayors’ kids all got addicted. Parents who’d imagined some glowing life script for their newborns years before were, as those kids reached young adulthood, confronted instead by late-night collect calls from jail, lying, stealing, conniving and that child’s body seemingly occupied by a mutant beast. Then came a felony record. Suddenly parents were co-signing for apartments, providing money and transportation for their addicted beloved, now 24, to take a GED class.

Though the number of actual addicts is small, the epidemic’s political impact has been substantial.

First because the states where the epidemic is most intense were crucial to the victor – whoever it was going to be.

Also, though, the opiate addiction rippled far beyond each individual addict. Addiction colored the lives of siblings, grandparents, uncles and aunts, friends and neighbors, pastors, teachers. As parents lost their fear of speaking out in the last two years, the problem emerged from the shadows, media coverage expanded, and now everyone for miles around was aware of it. County budgets buckled. Merchants saw theft increasing.

In several counties I visited, employers reported that more than half their job applicants couldn’t pass a drug screen. So though unemployment numbers fell, a good chunk of that was because many people were too hooked to seek work. Imagine what that does to a county’s productivity, and its buoyancy of spirit. It explains how a declining unemployment rate could create not optimism, but the foreboding that seemed to motivate many voters.

People also grew to understand that virtually all our heroin comes from or through Mexico – which is why it is cheaper and more potent than ever in our history. That did nothing to engender love for our southern neighbor in regions that had lost factories as well as kids. Nor did it make them feel that we have a serious and modern partner in Mexico when it comes to criminal justice and law enforcement.

This story plays out today with intensity in several of the states crucial to Trump’s victory – Ohio, North Carolina, Pennsylvania. It does the same in states he was assumed to win: West Virginia, Oklahoma, Utah, Kentucky, Indiana, Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and others. That these states – largely rural, religious, and white – are now our heroin beltways amounts to a stunning change in our national culture and one that most people in those areas became aware of only recently.

Equally stunning is that New York, California and Illinois – including New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, once our heroin hotspots – are well down the list of states ranked by addiction rates. Hillary Clinton won each of them.

In many of the most affected regions, moreover, people, by and large, have taken as self-evident Ronald Reagan’s dictum that “government is the problem” — the starkest threat to personal freedom. The private sector and the free market are, therefore, to be exalted; government starved. (This despite a deep reliance on government programs: Medicaid, Medicare, SSI, SSDI, worker’s compensation, food stamps, welfare, farm subsidies, etc.) Confederate flags and 2nd Amendment bumper stickers were common amid the Trump signs I saw.

The irony is that behind this drug plague is a story of how the private sector introduced the most serious widespread threat to personal freedom in America today – opiate addiction. All profits from the massive prescribing of narcotic pain pills have accrued to the private sector, mainly pharmaceutical companies; all costs of addiction to those pills, and then heroin, are borne by  the public sector. Indeed, for years, about the only people fighting the opiate scourge, my research showed, were government employees: cops and prosecutors, public health nurses and CDC statisticians, county social workers, judges and ER doctors, DEA agents, coroners and others.

the public sector. Indeed, for years, about the only people fighting the opiate scourge, my research showed, were government employees: cops and prosecutors, public health nurses and CDC statisticians, county social workers, judges and ER doctors, DEA agents, coroners and others.

The Sackler family, which owns Purdue Pharma, the company that makes OxyContin, has been estimated by Forbes magazine to be now one of the country’s wealthiest, with an estimated net worth of $14 billion, due to $35 billion in sales of the drug since it was released in 1996.

All this, I believe, helps explain the reception to Donald Trump’s populist message – including rejection of free trade and other sacred cows of Republican elites and conservative theorists. (“Worst Election Ever” proclaimed a post-election article from the conservative Hoover Institution.)

In these areas, too, the “throw away the key” approach to drug addiction was unquestioned dogma until the opiate scourge. That is changing. Democrats may still not get elected in a region like northern Kentucky, for instance, but Republicans who talk only tough on crime now have a hard time there, too – so harsh is the pill and heroin problem.

It’s likely that many of the regions where Trump enjoyed such support will require massive investment in drug treatment before they can be great again. (Ohio Gov. John Kasich realized that and went around his Republican-led state legislature a couple years ago to mandate Medicaid coverage for all Ohioans — largely because it gave people coverage for drug treatment.)

Will such an investment come from a president whose election seems to have so much to do with the opiate epidemic, yet who appears to have thought little about how to expand drug treatment?

How will people in these areas react to dismantling Obamacare, which provides coverage for addiction treatment that they didn’t have before?

In counties where half of job applicants fail drug screens, will the chambers of commerce line up to do away with the system?

Like so much that sprang from those Heartland yard signs, I guess we’ll see.

The post Donald Trump & Opiates in America appeared first on .

November 18, 2016

Community and CEOs

Folks who have heard me speak know that that community-building behavior by CEOs is something I admire and long for more of, nowadays particularly. Jack Brown, CEO of Stater Bros. Markets, is now my

hero.

A story in today’s LA Times reports the death of Mr. Brown, though folks in Southern California will recognize his com pany as a household brand name. We lived near a Stater Bros. Market when we were growing up and shopped there all the time.

pany as a household brand name. We lived near a Stater Bros. Market when we were growing up and shopped there all the time.

Sadly, before his death, I was unaware of Brown’s story, of his philanthropy and decision to not move the company HQ from its base in San Bernardino, a tough town that didn’t need any more companies leaving. He founded the Boys and Girls club of San Bernardino and the Children’s Fund of San Bernardino.

Too often CEOs have their own wealth lining in mind. I’m reminded of the behavior of the CEO of Wells Fargo, who oversaw a lot of unethical stuff, then fired the mid-level folks who were allegedly ordered to perpetrate it, then retired with a $124 million paycheck.

The story of U.S. capitalism over the last generation or two is replete with guys behaving in this way. Shredded communities are the result. So is, if you ask me, our national opiate epidemic.

Communities, seems to me, are built by many people. But an important part of that are the decisions made by company owners and managers. Those decisions can crush, or enliven, a community. Too often, in the recent history of our country, it’s the former.

Sounds like Jack Brown retired fairly wealthy for doing the right thing. That’s the way it should be.

The post Community and CEOs appeared first on .

November 8, 2016

24-Hour News – Just Like Heroin

24-Hour News is just like heroin.

We pretend we’re informed by it. In reality, we know that each network is a dealer in the drug of outrage. Each provides little information or depth. Instead they concoct a diet of heat, alarm, frenzy. Above all, they provide us a drenching isolation that separates us from our fellow Americans.

One sign of a heroin addict is that he forsakes family, old friends and community to hang out with others who use and sell dope. They talk about dope constantly and don’t understand those who don’t find that topic endlessly fascinating.

That’s what 24-Hour News has done to us, and our body politic. Forced us into little bubbles of people, all of whom think and talk alike and don’t understand anyone in the other bubbles who don’t think and talk like them. We all know this is true.

Which is why I say 24-Hour News is just like heroin.

So this election day, after we vote, let’s do another civic duty: Let’s all turn off 24-hour news, and talk radio, too, for that  matter.

matter.

For good! Just block them all. Easy to do by clicking here. Each station. CNN, FOX, MSNBC, Headline News. The problem is the format, not the network itself.

24-Hour News assumes that every issue has only two sides to it, and we can neatly know what they are, and that once a position is staked out, we cannot waver from it. It picks and pricks at some topics well beyond any presumed responsibility of informing the public is fulfilled. Yet somehow it does this while rarely providing any deep or nuanced understanding. And other issues is doesn’t touch at all.

It Monday-morning-quarterbacks public servants and elected officials to death.

All because it has to fill that time.

Meanwhile, these networks bundle most issues into five-minute, in-between-the-commercials, pre-digested packets. I’ve been on several of these and I now boycott them. I was on a CNN segment once that discussed the Mexican drug war – in six minutes with two other guests. We cannot possibly learn a thing about that very important issue in so short a time.

24-Hour News is one of the most corrosive influences on our democracy. Doping it. Distracting it. Numbing it. Lowering our standards for what “news” is and how much participation is actually required of us to preserve a functioning republic.

Never has 24-Hour News failed us more harmfully than in this presidential campaign. Its anchors spent most of the pre-convention months analyzing incessantly whether Candidate X had a pathway to the nomination. The horse race is all those networks cared about. It was a narcotic that had us all distracted.

We need real journalism. We got junk food. We needed deep discussions of complicated issues. We got yammering, blather, screeching and babble – usually designed to make us feel outraged at everyone else and confirmed in the righteousness of our own behavior and thinking.

In other words, we got dope.

For that’s what heroin does to an addict: convinces him that the path he’s on is the right one and no other is conceivable.

As Americans, we spend a lot of time worrying about what we consume, avoiding processed foods, cigarettes, sodas.

Why don’t we have the same concern for our civic consumption?

Some who block 24-Hour News may suffer withdrawals at first. Shiver and shake and not be able to sleep. But that’ll pass. My bet is they’ll emerge with a fresher, brighter outlook on life. They won’t be angry or outraged at their fellow Americans all the time.

Another thing: Recovering addicts find life without dope to be complicated without that Silver Bullet to remove their worries. So, too, might folks recovering from 24-Hour News.

Just as heroin takes our cares away, the 24-Hour News Syndrome relieves us of the tough work involved in being Americans. We don’t actually have to strive to develop an opinion when 24-hour News provides it to us.

So we will have to develop our own opinions without the help of an anchor and a 5-minute expert there to enrage us and keep us tuned in through the upcoming commercial break. It may mean reading more. A wider range of opinion or news stories. Books or magazine articles. But the last place to find real information on anything worth knowing about is at a five-minute snippet of yammering talking heads. We know this is true.

But if Americans are exceptional, it’s through this work required of us in citizenship, civic participation, and in being accountable for our political and consumer choices. This is the job description of being an American, seems to me.

“A Republic, if you can keep it,” said Ben Franklin to the woman who asked what the Constitutional Convention had just created.

We got away from that, from what’s best about America. We opted for easy – easy solutions to pain, quick and easy answers to complicated problems, easy substitutes to civic participation. Convenience and comfort over all else.

In doing so, we rid ourselves of things so essential that they have no price … and in return we have been invaded by cheap crap.

So today, Be An American!

Please go vote!

Then come home and block every 24-hour new station on your TV.

We need to keep this Republic for a while.

The post 24-Hour News – Just Like Heroin appeared first on .

October 26, 2016

Cab Calloway High School

Tomorrow (Thursday) I’ll be speaking at Cab Calloway High School of the Arts in Wilmington, Delaware.

The speech is open to the public and I’ll be talking about opiate addiction, America and Dreamland. Delaware, like so many parts of the country, is awash in opiate addiction and all its consequences.

But I love the idea that the school is named for Cab Calloway, an orchestra leader I’ve loved since I was a kid and first heard “Minnie the Moocher” (I was in junior high, I think). Here he is with the Nicholas Brothers, stunning tap dancers.

The school’s first board president was his daughter, Cabella Calloway. He had moved to Delaware shortly before the school was founded in 1992 and was involved in its formation before his death in 1994.

By the way, the school’s marching band has won the championship in its area six of the last seven years. Nice! Next Sunday, they’re in Hershey PA competing in the Atlantic Coast Tournament of Bands.

Good luck to the Cab Calloway High School Marching Band! A name like that, you better win! How could you not?

I’d love to see a marching band named for Cab Calloway.

The post Cab Calloway High School appeared first on .

October 16, 2016

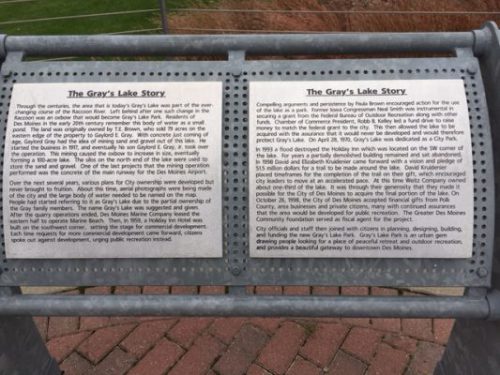

Gray’s Lake and Grandparents’ Stories

My grandmother, Paula Brown, was a gadfly in Des Moines, Iowa, fighting McDonald’s garish golden arches and trying to save old buildings. Because of her, my mother didn’t allow us to eat at McDonald’s. I didn’t have my first Big Mac until I was 12 and it didn’t do much for me. (I think I’ve had three or four – the sum total of all McDonald’s burgers of any kind I’ve had in my life.)

I spent a day last week in Des Moines, Iowa, where I spoke to a convention of county Medical Examiners.

It was my first time in the city since I was 14. We went on several cross-country car trips from California to D es Moines when I was a kid.

es Moines when I was a kid.

My grandfather owned an engineering company.

My grandmother also fought, successfully, to preserve what’s known as Gray’s Lake, south of downtown Des Moines, and keep it from commercial development and motor boats.

I suspect most folks in Des Moines are happy she did. She’s mentioned on a plaque at the lake.

The city has clearly put some energy into preserving the lake and its surroundings, while making it useful to folks. It’s now a park – a beautiful, quiet part of the city, with a bike path and footpath around it, rowboats and a small concession stand. People, one fellow told me, use Gray’s Lake relentlessly in Des Moines.

I’m proud that she did that. I’m betting most people would love something like Gray’s Lake – free of speedboats and Applebee’s – as part of their town.

Made me think of heritage. My grandfather fought in Patton’s Army during World War II. That’s on my mother’s side.

A few months ago, my daughter and I went to NYC and to Ellis Island and found records of the man I believe is my grandfather on my dad’s side. Lauraino Quinones is the spelling we found – a fellow from Spain, born in 1900, who took a boat from the Dominican Republic and landed in Ellis Island in 1922.

The real spelling of my grandfather’s name was Laureano, so I don’t know if this is his record, but everything else matches up.

He had a story out of a novel. He was born an illegitimate son in 1900 in a small Atlantic Coast village in Spain. His mother, whose husband had abandoned her years before, left the boy with uncles and fled to Argentina to escape the scandal and was never heard from again.

He grew up with no one, I suppose, and when he was 20 he joined the Spanish merchant marine, jumped ship in Puerto Rico, cut sugar cane for two years, and then in about 1922 or so, made his way to NYC, and eventually to Allentown, Pennsylvania, where in due course he met my grandmother, Elena Matracino, from a large family of Italian immigrants.

He worked in a brewery and she in a sewing factory. They both died before I was born.

But I love those stories – I’m connected to Italian and Spanish peasants, Oklahoma farmers, somewhere in there we’re supposed to be related to Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, and there is, I’m told, some Cherokee Indian as well.

All of that got mixed and mashed and, as it should, was turned into something else, new in America.

The post Gray’s Lake and Grandparents’ Stories appeared first on .

October 9, 2016

Judge Moses’ Court

I was in the town of Logan, Ohio last week, at the tail end of my speaking tour through Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky and Indiana.

Logan, pop. 7,000, is an Appalachian coal town in the county of Hocking, about 40 miles southeast of Columbus in the farmland off of state Highway 33.

The morning after my talk, I spent an hour in the town’s drug court, which is now dedicated entirely to people with opiate addictions trying to expunge criminal records and keep their recovery going.

The court is run by Judge Fred Moses, who in this court looks and sounds more like a social worker. He asks each client about his or her recovery, job prospects, children – confers with prosecutors and probation and social workers. The idea behind drug court is that clients must get into addiction recovery, begin to repair their lives, before any record expunging takes place.

What struck me was, first, that there were such a court at all in a town like Logan. And then that all the 10 or so clients I met that day were addicted to opiates, heroin mostly.

All but one started into addiction on pain pills. A few began using them after they were prescribed the pills for some medical reason. Others began using them recreationally. But all of them got into their addiction because of the pervasive, massive supply of these pills that were, and are, available.

In Logan, according to a recovering addict I spoke with (whose interview I’ll post later), pain pills and benzodiazapines, and the insistence with which clients demand them, have made docs unimaginative it seems. At least, pills appear to be many physicians’ immediate go-to response.

Judge Moses has most of his clients on Vivitrol, the opiate blocker, paid for by Medicaid, which, in Ohio, has been available to anyone since 2014. This is due to a Republican governor, John Kasich, who expanded coverage to all Ohioans, largely, from what I understand, to give people without insurance access to addiction treatment – so big was the state’s problem.

Without that, Vivitrol would be too expensive for Hocking County. Sitting there that day, I wondered if at some point every heroin addict in America will have to be on Vivitrol.

Judge Moses’ drug court is a standing testament to how opiate addiction is changing minds in rural areas. I suppose there was a time when the idea of giving a drug to combat drug addiction was viewed askance in Hocking County. But this addiction is different and requires different response. Hence Vivitrol.

What also struck me, though, was that this scourge spread across the country largely due to the private sector – pharmaceutical companies and doctors, urging the aggressive prescribing of narcotic painkillers.

There’s a role we all have, as American health consumers, in what’s taken place, and it’s an important one. But it’s striking to me how this began due to the private sector – not underground drug traffickers – and how the profits have accrued to the private sector.

Yet dealing with the collateral damage has been charged almost entirely to the public sector: ERs, public health departments, cops, prosecutors, jails … and drug court, like the one run by Judge Fred Moses in the small town of Logan, Ohio.

I wish his clients well, as I do the town of Logan itself, where I met a lot of nice people (and received this Proclamation), and which now must battle this kind of persistent, costly addiction along with all the other issues facing small-town, rural America.

The post Judge Moses’ Court appeared first on .

October 3, 2016

Dr. Procter’s House

I’m speaking today in a mansion near Portsmouth Ohio built by a doctor named David Procter – known around here as `The Godfather of the Pill Mill’ – whose story I told in Dreamland.

A reader I’ll call Karen, who grew up in Portsmouth, wrote to me a while ago:

“For some reason I feel compelled to tell you that Dr. Procter was the catalyst that destroyed my family.

The house, in South Shore, Kentucky on the Ohio River, has been converted to a  drug rehabilitation clinic run by a company called Recovery Works.

drug rehabilitation clinic run by a company called Recovery Works.

Karen:

“My dad worked at the prison as a guard. He hurt his back, falling from a ladder during some sort of training assignment.

“I only knew that my dad got hurt at work, and [Procter] was his doctor. And that my mom hated him with a passion. I can remember going to his office and my mom coming out so upset. I found later that it was because she would go there and beg him to stop giving my dad pills. Lines out the door. I can still remember my mom and my aunt and my grandmother in the car discussing all the people.

___

Pharmaceutical companies and pain specialists viewed the pain-pill revolution that transformed American medicine as a boon to doctors. They sold the opiate painkiller pill as a way of addressing the lack of time doctors had with patients, and pain patients in particular.

That doctors accepted them so readily tells us how serious were the time pressures they felt.

The more you prescribed them, though, the more the pills became a curse – just like morphine molecule they contained. They wore down a doctor. A doctor known as an easy touch was soon overwhelmed with patients who filled his waiting room, waving cash in front of him, insisting. Soon he was accepting only cash – addicted to it, accepting the lies his patients told him, believing too that nothing was wrong.

From this emerged the medical mutation known as the Pill Mill. Nothing showed the corrosive effects of for-profit medicine like the pill mill.

David Procter was notorious in Portsmouth for prescribing large amount of pain pills to patients, with almost no diagnosis.

___

“The day my parents marriage finally ended, was the day my mother threw all of my dad’s pills Down The Gutter and he removed the manhole cover and crawled down to get them. I remember her taking her wedding ring off then and telling him that she wanted a divorce. His head was literally sticking out of the manhole. Sad time.” Karen

___

David Procter was a product of that, I believe.

He had come in 1977, and been beloved. Amid economic decline, doctors held the key to life strategies like worker’s comp and SSI. Procter became the quickest doc around in preparing worker’s comp papers.

In 1988, the Kentucky Board of Medical Licensure investigated him for the first time. Those reports seem to describe a man losing his bearings but still trying to maintain some semblance of medical and moral rectitude, still looking for second opinions and trying to find alternatives to pills for his pain patients.

Ten years later, a second investigation, and that doctor had vanished.

In the interim, OxyContin and the Pain Revolution had come. Jobs were gone, Main Street was an empty shell. Ohio River towns had lost huge population. Dreamland pool had closed.

As a doctor in a desperate place, he had been unaccountable for too long and grown corrupt, the Kentucky public record documents. Now, investigators found a man who extorted sex for pills from vulnerable and addicted women, who preyed on girls tormented about abortions. His waiting room was a corral of drug addicts, all there with eyes downcast, desperate. He stayed open well past his posted business hours. His records were shoddy or nonexistent.

After a car accident, he began hiring doctors with drug and alcohol problems to run his clinics. This is what gave him lasting importance to this story, for those doctors in turn left to start their own pain clinics.

The problem metastasized like a cancer. Procter became the Ray Kroc of the Pill Mill.

__

Drugs have hit my family hard. My uncle’s stepdaughter and her daughter were both murdered in Lucasville. They still haven’t found their murderers. The daughter was a beautiful sixteen-year-old girl who didn’t deserve anything that she got. Apparently her mother was selling Oxycontin. My aunt’s step-daughter is doing life right now for murdering another girl in a town near Portsmouth. I have two uncles who both died of heroin overdoses in the last 6 years.

And some of my friends from high school, their daughter has been missing for about 6 years. Due to drugs as well, I’m sure of it. I could go on and on. I’m so glad that I left that area in 1989 and made a better life for myself. However the county that I am living in and have been living in for 27 years is starting to feel the sting. It’s happening. Karen

___

David Procter eventually went to prison for 12 years. He was released in 2014 and, being Canadian, was  deported. He leaves behind a strange painting of a monkey looking into a mirror, with Dr. Procter’s reflection looking back at him, and a seven-bedroom, six-bath, seven-car mansion on 34 acres that is now occupied by 16 addicts working on their recovery.

deported. He leaves behind a strange painting of a monkey looking into a mirror, with Dr. Procter’s reflection looking back at him, and a seven-bedroom, six-bath, seven-car mansion on 34 acres that is now occupied by 16 addicts working on their recovery.

____

My dad OD’d in 2009, but he really died years before. He was a good dad once. I’m glad that I have those happy memories.

I know Procter’s house well. We always called it the house that pills built. Beautiful place. Fitting that it’s now a rehab. Karen

The post Dr. Procter’s House appeared first on .