Alex Kudera's Blog, page 133

August 21, 2013

1909

In the basement stacks, I chance upon Jillian Weise's

The Amputee's Guide to Sex

and the first poem I turn to, "The Scar On Her Neck," mentions the year 1909 in its fourth two-line stanza: "Appolinaire was held captive/ in 1909, on suspicions he stole/ the Mona Lisa."

I don't recall F. D. Reeve mentioning this tidbit in his 1909 course, but I'm sure he would have appreciated it.

Anyway, I was down there, at the bottom of Cooper Library where literature is known to dwell, trying to hunt down some of Reeve's writing as well as the Harry Mathews novel he'd recommended to me twenty-two years ago. As it turned out, Clemson doesn't own a copy of The Sinking of Odradek Stadium or the Reeve I was most interested in, his Robert Frost in Russia , but I did find a Reeve edited Great Soviet Short Stories as well as Harry Mathews's far more recent My Life in CIA . It all came full circle when it turned out the only slim volume of Harry Mathews on the shelf had as it series editor Clemson's own Frank Day, a professor whose status was "emeritus" when I shared an office with him for half a semester during in the spring of 2008, my second semester in the South.

Alas, now it's time to leave poetry and fiction writing and get back to the basic business of business writing. My life in general ed. . .

I don't recall F. D. Reeve mentioning this tidbit in his 1909 course, but I'm sure he would have appreciated it.

Anyway, I was down there, at the bottom of Cooper Library where literature is known to dwell, trying to hunt down some of Reeve's writing as well as the Harry Mathews novel he'd recommended to me twenty-two years ago. As it turned out, Clemson doesn't own a copy of The Sinking of Odradek Stadium or the Reeve I was most interested in, his Robert Frost in Russia , but I did find a Reeve edited Great Soviet Short Stories as well as Harry Mathews's far more recent My Life in CIA . It all came full circle when it turned out the only slim volume of Harry Mathews on the shelf had as it series editor Clemson's own Frank Day, a professor whose status was "emeritus" when I shared an office with him for half a semester during in the spring of 2008, my second semester in the South.

Alas, now it's time to leave poetry and fiction writing and get back to the basic business of business writing. My life in general ed. . .

Published on August 21, 2013 19:25

August 19, 2013

F. D. Reeve

The spectacular intellectual as polyglot and bricoleur, Professor F. D. Reeve, passed away this summer. He was one of my favorite professors and personalities at Wesleyan University, and in the spring of 1991, I was fortunate enough to be enrolled in his 1909 class. Against the common catalog of course titles such as "classical philosophy," "modern poetry," and "Soviet literature," this was probably the most creative idea for a class I'd ever encountered.

The conceit of the seminar was that everything assigned, and there was too much good stuff to list here, was either written in 1909 or concerned that year or its neighbors, the turn of the century, etc. A main theme of the class was that despite American and French revolutions that had occurred over 100 years previously, the turn of the century was when class boundaries truly began to dissolve and the "Western world" moved into a distinctly more egalitarian period. Of course, Professor Reeve had a sense of humor about such sweeping period divisions, and his humor was partly why the once-a-week seminar was fun to attend.

So it's with some irony then, that for financial reasons, concerning money, if not class exactly, I had to graduate in seven semesters and shove almost seven course credits (equivalent to twenty-one credits at most schools) into that final season of Wes. For this reason, I certainly couldn't read every three- to five-hundred pager included on his book-a-week syllabus, but Professor Reeve did say all kind of unusual things when we'd meet, and a couple readings I enjoyed were Carl Schorske's Fin-De-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture and Roger Shattuck's The Banquet Years.

F. D. Reeve was indeed Superman's father, or I should say that the actor Christopher Reeve was his son. Reeve Sr. was a larger than life figure and the kind of prolific talent who wrote novels, poetry, criticism, and then did translation in his spare time. Yes, quantity and range of publication should not be seen as everything, but with all overworked adjunct issues aside, Dr. Reeve was the sort of fellow who could make the rest of us walking into classrooms and calling ourselves "professors" feel somewhat like we're merely pretending, and our ranks are no doubt full of folks too scared or dishonest to admit as much. (This is one reason I always tell students to call me "Alex" unless that makes them uncomfortable.)

Around the time I was in Reeve's class, most likely summer of 1990 or 1991, he appeared at the Borders Book Shop in Philadelphia, the old one at 1727 Walnut Street off Rittenhouse Square and gave on-the-spot translation of a famous Russian poet. That Borders would be where I first worked after college, and those bookselling years were when I did my most substantial drafting of Cartoon Bubbles from a City Underwater, at the time titled The Appendix on Spark Park Poops (indeed!). Although I was reading a lot of fiction by John Barth, T.C. Boyle, and Don Delillo, I'd also dabble in philosophy, "critical theory," history, and the rest of it, so I enjoyed the fact that the old Borders had a copy of Reeve's The White Monk: an essay on Dostoevsky and Melville on the shelf. The policy soon changed, but when I worked there in the early nineties, Borders would procure a single copy of thousands of academic books, not merely the Michel Foucaults as Vintage paperbacks or Simon Schamas with glossy pages and photos, and the store was its own incredible contemporary library.

Before I drift too far from Reeve, I wanted to mention that Professor Licht from The Betrayal of Times of Peace and Prosperity is not Professor Reeve (and the Ward campus is not Wesleyan), but if I'm not mistaken, Superman's dad did bring a bottle of white wine and Dixie cups to our last seminar meeting, and so he is in a way an inspiration for my fictional character although he didn't say or do anything that Herr Licht does or says in my story.

I took reading courses almost exclusively as an undergrad, mainly history, political philosophy, and literature, and I handed in fiction three times for assignments, and he is one of two professors to be quite encouraging with his comments (the third fellow regretted that I wasn't funny). Anyone who has had me as a teacher, read me as a blogger, or spoken to me on the phone might appreciate that although Reeve's comments were generally positive, he suggested I hold off on the "ramblin'" and also that I read The Sinking of The Odradek Stadium by Harry Matthews. For whatever reason, I never read the book, but in honor of Reeve's passing, I'll try to do so this school year.

I hope I return to this and clean it up, maybe make the words conform more to the mood or moment of obituary, but for now, here is more information about Professor Reeve's life and work, and here is a Wesleyan Connection notice and writing from Wesleyan's current king of the MOOC, I mean president. (Roth's course on "The Modern and the Postmodern" seemed to be a free, fantastic online course I toyed with enrolling in even as I wondered about its negative economic impact on the rest of us knowledge cogs.) I learned of Reeve's passing somewhere on the homepage of The New York Times, but at the time of this writing I was unable to find that obituary.

Thank you, F. D. Reeve.

The conceit of the seminar was that everything assigned, and there was too much good stuff to list here, was either written in 1909 or concerned that year or its neighbors, the turn of the century, etc. A main theme of the class was that despite American and French revolutions that had occurred over 100 years previously, the turn of the century was when class boundaries truly began to dissolve and the "Western world" moved into a distinctly more egalitarian period. Of course, Professor Reeve had a sense of humor about such sweeping period divisions, and his humor was partly why the once-a-week seminar was fun to attend.

So it's with some irony then, that for financial reasons, concerning money, if not class exactly, I had to graduate in seven semesters and shove almost seven course credits (equivalent to twenty-one credits at most schools) into that final season of Wes. For this reason, I certainly couldn't read every three- to five-hundred pager included on his book-a-week syllabus, but Professor Reeve did say all kind of unusual things when we'd meet, and a couple readings I enjoyed were Carl Schorske's Fin-De-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture and Roger Shattuck's The Banquet Years.

F. D. Reeve was indeed Superman's father, or I should say that the actor Christopher Reeve was his son. Reeve Sr. was a larger than life figure and the kind of prolific talent who wrote novels, poetry, criticism, and then did translation in his spare time. Yes, quantity and range of publication should not be seen as everything, but with all overworked adjunct issues aside, Dr. Reeve was the sort of fellow who could make the rest of us walking into classrooms and calling ourselves "professors" feel somewhat like we're merely pretending, and our ranks are no doubt full of folks too scared or dishonest to admit as much. (This is one reason I always tell students to call me "Alex" unless that makes them uncomfortable.)

Around the time I was in Reeve's class, most likely summer of 1990 or 1991, he appeared at the Borders Book Shop in Philadelphia, the old one at 1727 Walnut Street off Rittenhouse Square and gave on-the-spot translation of a famous Russian poet. That Borders would be where I first worked after college, and those bookselling years were when I did my most substantial drafting of Cartoon Bubbles from a City Underwater, at the time titled The Appendix on Spark Park Poops (indeed!). Although I was reading a lot of fiction by John Barth, T.C. Boyle, and Don Delillo, I'd also dabble in philosophy, "critical theory," history, and the rest of it, so I enjoyed the fact that the old Borders had a copy of Reeve's The White Monk: an essay on Dostoevsky and Melville on the shelf. The policy soon changed, but when I worked there in the early nineties, Borders would procure a single copy of thousands of academic books, not merely the Michel Foucaults as Vintage paperbacks or Simon Schamas with glossy pages and photos, and the store was its own incredible contemporary library.

Before I drift too far from Reeve, I wanted to mention that Professor Licht from The Betrayal of Times of Peace and Prosperity is not Professor Reeve (and the Ward campus is not Wesleyan), but if I'm not mistaken, Superman's dad did bring a bottle of white wine and Dixie cups to our last seminar meeting, and so he is in a way an inspiration for my fictional character although he didn't say or do anything that Herr Licht does or says in my story.

I took reading courses almost exclusively as an undergrad, mainly history, political philosophy, and literature, and I handed in fiction three times for assignments, and he is one of two professors to be quite encouraging with his comments (the third fellow regretted that I wasn't funny). Anyone who has had me as a teacher, read me as a blogger, or spoken to me on the phone might appreciate that although Reeve's comments were generally positive, he suggested I hold off on the "ramblin'" and also that I read The Sinking of The Odradek Stadium by Harry Matthews. For whatever reason, I never read the book, but in honor of Reeve's passing, I'll try to do so this school year.

I hope I return to this and clean it up, maybe make the words conform more to the mood or moment of obituary, but for now, here is more information about Professor Reeve's life and work, and here is a Wesleyan Connection notice and writing from Wesleyan's current king of the MOOC, I mean president. (Roth's course on "The Modern and the Postmodern" seemed to be a free, fantastic online course I toyed with enrolling in even as I wondered about its negative economic impact on the rest of us knowledge cogs.) I learned of Reeve's passing somewhere on the homepage of The New York Times, but at the time of this writing I was unable to find that obituary.

Thank you, F. D. Reeve.

Published on August 19, 2013 07:51

August 10, 2013

44

Another thing I liked about Dan Fante's Point Doom is that the narrator is 44 years old when the action takes place. It made me feel like a bit less of a failure, reading about this other 44-year-old who can barely stay sober and off his mom's couch. (It should be noted that I'm writing this from a soft chair in my mother's living-room area although that isn't my permanent residence.)

Also, I'm almost certain there was a 44-year-old lurking in the shadows of the next novel I read, Dave Newman's gritty and delightful Raymond Carver Will Not Raise Our Children , but I don't think it was Richard, a background character and officemate who I could relate to somewhat in his sensitivity to the meanness of an aggressive student (I should say, thankfully, no student has ever thrust a pen at my head). I also just found this great review of that book that mentioned Fante and his buddy Mark SaFranko in the first paragraph.

My daughter knows I'm 44, and for fun, she told a 66-year-old that I was 88.

Also, I'm almost certain there was a 44-year-old lurking in the shadows of the next novel I read, Dave Newman's gritty and delightful Raymond Carver Will Not Raise Our Children , but I don't think it was Richard, a background character and officemate who I could relate to somewhat in his sensitivity to the meanness of an aggressive student (I should say, thankfully, no student has ever thrust a pen at my head). I also just found this great review of that book that mentioned Fante and his buddy Mark SaFranko in the first paragraph.

My daughter knows I'm 44, and for fun, she told a 66-year-old that I was 88.

Published on August 10, 2013 22:02

July 29, 2013

Kerouac, Fante, a few others dropped in without supporting detail

So I'm thirty-five pages from the end of Point Doom, the serial-killer novel I had to step back from, and twenty-six pages from the end of The Dharma Bums, the Kerouac does Zen and backpacking I sought safety in, and I just remembered that the two have also intersected within the text, and this could be another reason Fante drove me back to Kerouac.

Early on the gritty SoCal AA mystery, Fante's protagonist notes:

Jack Kerouac once wrote that "the only people for me are the mad ones. . . who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn burn burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars."

That's crap, but thanks, Jack. For the last few years in New York I'd tried to be one of Jack's people. In my spare time I wrote a book of poems and, before he died, I had even worked with my dad, Jimmy Fiorella, and coauthored a couple of screenplays, but eventually I discovered the truth about Kerouac, that crap, and those people: most of them wind up in the bughouse or with a mouthful of broken teeth and a jar of Xanax. Or worse. They wind up OD'd and dead. (13)

Fante has a point about romanticizing alcoholism, drug abuse, unemployment, homelessness, and the rest of gritty reality that sets in when the candles burn down and away, but Kerouac of The Dharma Bums seems much more "chill" that this famous quotation suggests.

At this point, I must confess I took a break from "typing" this blog (et tu, Capote), and returned to the Kerouac, and so I'm now within twenty pages of the end.

Alas, I took two breaks, and now I'm finished the book. For the most part, I liked the mood of the book and the descriptions of nature, and even the wild, all-night party sections were okay although I'd recommend Pynchon's V for that kind of party scene.

Okay, back to Fante and then maybe Norman Rush, Philip Roth, or David Lodge comes next. These slightly higher-brow writers are ones I've also enjoyed reading in 2013, and this summer, I also read and liked very much the afore-dissed Truman Capote's "Children on their Birthdays."

Sorry I meander and weave and provide so little detail.

Early on the gritty SoCal AA mystery, Fante's protagonist notes:

Jack Kerouac once wrote that "the only people for me are the mad ones. . . who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn burn burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars."

That's crap, but thanks, Jack. For the last few years in New York I'd tried to be one of Jack's people. In my spare time I wrote a book of poems and, before he died, I had even worked with my dad, Jimmy Fiorella, and coauthored a couple of screenplays, but eventually I discovered the truth about Kerouac, that crap, and those people: most of them wind up in the bughouse or with a mouthful of broken teeth and a jar of Xanax. Or worse. They wind up OD'd and dead. (13)

Fante has a point about romanticizing alcoholism, drug abuse, unemployment, homelessness, and the rest of gritty reality that sets in when the candles burn down and away, but Kerouac of The Dharma Bums seems much more "chill" that this famous quotation suggests.

At this point, I must confess I took a break from "typing" this blog (et tu, Capote), and returned to the Kerouac, and so I'm now within twenty pages of the end.

Alas, I took two breaks, and now I'm finished the book. For the most part, I liked the mood of the book and the descriptions of nature, and even the wild, all-night party sections were okay although I'd recommend Pynchon's V for that kind of party scene.

Okay, back to Fante and then maybe Norman Rush, Philip Roth, or David Lodge comes next. These slightly higher-brow writers are ones I've also enjoyed reading in 2013, and this summer, I also read and liked very much the afore-dissed Truman Capote's "Children on their Birthdays."

Sorry I meander and weave and provide so little detail.

Published on July 29, 2013 12:34

July 26, 2013

they aren't "mooching"

CNN had the audacity to post this "mooching millennial" headline on the homepage in the Business section just below an image of and article on Detroit's new 444 million-dollar arena (yes, that Detroit, the bankrupt one). Even if by some miracle this isn't largely corporate welfare funded by taxpayers, the paring of these two headlines is gruesome. An entire generation, our 18 to 34-year-olds are taking on the greatest college debt in our history, facing a tough job market, and thus many are forced to live at home, and yet they are labeled as "mooching." Closer to home, our kids in South Carolina are facing higher tuition each year while the Governor receives two years of stadium suite space valued at $58,000.

It never ends.

Published on July 26, 2013 19:17

July 24, 2013

Russell Banks on Jack Kerouac

I'm rereading Jack Kerouac's The Dharma Bums, the only Kerouac I read as a young man, and because it did not make much of an impression, I didn't return to him to try

On the Road

until twenty years later. The return was mainly because I'd begun teaching a course called "contemporary literature" and felt obliged to have some familiarity with Kerouac and The Beats.

In my current couple weeks of accidental single-parenting, I'm finding The Dharma Bums to be surprisingly enjoyable and a welcome escape, this reading about younger writers with the time and energy to run screaming down mountains, in this case, Matterhorn.

Anyway, via a tweet, I just chanced upon this Russell Banks interview response from The Paris Review (Summer, 1998):

INTERVIEWER You began to write in the 1960s. How did that decade influence you? Did you meet any notable figures?

RUSSELL BANKS Yes, I met Kerouac. It must have been 1967, a year or two at the most before he died. I got a call from a pal in a bar in town, The Tempo Room, a local hangout—Jack Kerouac is in town with a couple of other guys and he wants to have a party. I said, Yeah, sure, right. He said, No, really. I was the only guy in this crowd with a regular house. So Jack Kerouac showed up with a troupe of about forty people he had gathered as he went along and three guys who he insisted—and I think they indeed were—Micmac Indians from Quebec. Kerouac, like a lot of writers of the open road, didn’t have a driver’s license. He needed a Neal Cassady just to get around; this time he had these crazy Indians who were driving him to Florida to be with his mother. They all ended up crashing for the weekend. He had just received his advance for what turned out to be his last book and was spending it like a sailor on leave. He brought with him a disruptiveness and wild disorder, and moments of brilliance too. I could see how attractive he must have been when he was young, both physically and intellectually. He was an incredibly beautiful man, but at that age (he was about forty-five) the alcohol had wreaked such destruction that it left him beautiful only from the neck up. Also, you could see why they called him Memory Babe—he would switch into long, beautiful twenty-minute recitations of Blake or the Upanishads or Hoagy Carmichael song lyrics. Then he would phase out and turn into an anti-Semitic, angry, fucked-up, tormented old drunk—a real know-nothing. It was comical, but sad. There were a lot of arguments back and forth, then we would realize that no, he’s just a sad, old drunk; I can’t take this stuff seriously. Eventually he would realize it himself and he would back off and turn himself into a senior literary figure and say, I can’t take that stuff seriously either. Every time he came forward, he would switch personas, and you would go bouncing back off him. It was a very strange and strenuous weekend. And very moving. It was the first time I had seen one of my literary heroes seem fragile and vulnerable.

In my current couple weeks of accidental single-parenting, I'm finding The Dharma Bums to be surprisingly enjoyable and a welcome escape, this reading about younger writers with the time and energy to run screaming down mountains, in this case, Matterhorn.

Anyway, via a tweet, I just chanced upon this Russell Banks interview response from The Paris Review (Summer, 1998):

INTERVIEWER You began to write in the 1960s. How did that decade influence you? Did you meet any notable figures?

RUSSELL BANKS Yes, I met Kerouac. It must have been 1967, a year or two at the most before he died. I got a call from a pal in a bar in town, The Tempo Room, a local hangout—Jack Kerouac is in town with a couple of other guys and he wants to have a party. I said, Yeah, sure, right. He said, No, really. I was the only guy in this crowd with a regular house. So Jack Kerouac showed up with a troupe of about forty people he had gathered as he went along and three guys who he insisted—and I think they indeed were—Micmac Indians from Quebec. Kerouac, like a lot of writers of the open road, didn’t have a driver’s license. He needed a Neal Cassady just to get around; this time he had these crazy Indians who were driving him to Florida to be with his mother. They all ended up crashing for the weekend. He had just received his advance for what turned out to be his last book and was spending it like a sailor on leave. He brought with him a disruptiveness and wild disorder, and moments of brilliance too. I could see how attractive he must have been when he was young, both physically and intellectually. He was an incredibly beautiful man, but at that age (he was about forty-five) the alcohol had wreaked such destruction that it left him beautiful only from the neck up. Also, you could see why they called him Memory Babe—he would switch into long, beautiful twenty-minute recitations of Blake or the Upanishads or Hoagy Carmichael song lyrics. Then he would phase out and turn into an anti-Semitic, angry, fucked-up, tormented old drunk—a real know-nothing. It was comical, but sad. There were a lot of arguments back and forth, then we would realize that no, he’s just a sad, old drunk; I can’t take this stuff seriously. Eventually he would realize it himself and he would back off and turn himself into a senior literary figure and say, I can’t take that stuff seriously either. Every time he came forward, he would switch personas, and you would go bouncing back off him. It was a very strange and strenuous weekend. And very moving. It was the first time I had seen one of my literary heroes seem fragile and vulnerable.

Published on July 24, 2013 03:28

July 22, 2013

pay

Ending on Isaac Sweeney's career progress seemed a bit too beyond the pessimistic pale of this blog, so I thought I'd return to my usual doom and gloom with this alternet piece on privatizing to reduce wages among janitors and cafeteria workers at charter schools.

This common tactic, that leads to downward pressure on wages for all "nonessential personnel," was something I noticed even in the 1990s, and it has always bothered me. Maybe the new healthcare law solves this problem, but for now, for most of my adult life, I've lived in a country where we tolerate food workers without access to healthcare serving school children. You don't have to be a "skilled professional" in any field to see how an illness exacerbated by lack of timely medical treatment could be far more expensive to society once hundreds of kids also become sick.

Although Philly.com posted this video on how absurd it is to use an 80-hour work week to teach employees how to budget money, they were also kind enough to post the good news on wages by using the distorting mean instead of median, so with a straight-faced headline they let us know that the "average American worker" earns $1,000 bucks a week. A good clarifying comment notes that we only have 100 million full-time workers (in a population over 300 million), and the median pay among them is in fact $763. I "googled" to follow that back to its source, the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Somewhere along the surf, I also stumbled upon the fact that within the private sector, one in four makes less than ten dollars an hour, and many more of us live desperately, terrified we could sink back under that modest level (400 bucks for a 40-hour work week before any taxes, housing, food, transportation, or healthcare costs are taken out).

If this is America in recovery. . .

This common tactic, that leads to downward pressure on wages for all "nonessential personnel," was something I noticed even in the 1990s, and it has always bothered me. Maybe the new healthcare law solves this problem, but for now, for most of my adult life, I've lived in a country where we tolerate food workers without access to healthcare serving school children. You don't have to be a "skilled professional" in any field to see how an illness exacerbated by lack of timely medical treatment could be far more expensive to society once hundreds of kids also become sick.

Although Philly.com posted this video on how absurd it is to use an 80-hour work week to teach employees how to budget money, they were also kind enough to post the good news on wages by using the distorting mean instead of median, so with a straight-faced headline they let us know that the "average American worker" earns $1,000 bucks a week. A good clarifying comment notes that we only have 100 million full-time workers (in a population over 300 million), and the median pay among them is in fact $763. I "googled" to follow that back to its source, the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Somewhere along the surf, I also stumbled upon the fact that within the private sector, one in four makes less than ten dollars an hour, and many more of us live desperately, terrified we could sink back under that modest level (400 bucks for a 40-hour work week before any taxes, housing, food, transportation, or healthcare costs are taken out).

If this is America in recovery. . .

Published on July 22, 2013 03:01

July 21, 2013

Holic and Sweeney

Within the last week, my copies of Nathan Holic's American Fraternity Man and Isaac Sweeney's

Same Track, Different Track

arrived by mail.

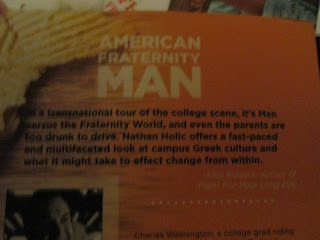

Holic's fast-paced novel has an absolutely fantastic cover, and of course, I was excited to see this blurb on the back:

Both writers are full-time teachers now, but both have paid their adjunct dues, and in different ways continue to support the cause of the more tangentially employed among us. For Atticus Review, Nathan has delivered six sets of graphic frames for

Fight for Your Long Day

, and Isaac continues to write about adjunct issues and more for

The Chronicle of Higher Education

. More or less, what we have are two early 30-somethings with small children working constantly to survive but also thinking of the less fortunate of higher education, whether they're instructors or students. I've already skimmed Isaac's book, and although I'd call most of what I read a nonfictional summary and assessment of how he fought his way out of the adjunct's life to land a full-time tenure-track job at a community college, in this telling, there is plenty of implied advice for adjuncts trying to do the same. Two key points from Isaac's experience are 1) apply early and often, many more jobs than you'd think would be necessary (this rings true as I remember a recent PhD comp/rhet grad applied to more than 100 positions to land one tenure-track job at a four-year school), and 2) also play to your strength during the teaching demonstration. For his TT campus visit, Isaac used a lesson he'd taught many times before, and he nailed it. For many of us, easier said than done, yes, indeed.

Both writers are full-time teachers now, but both have paid their adjunct dues, and in different ways continue to support the cause of the more tangentially employed among us. For Atticus Review, Nathan has delivered six sets of graphic frames for

Fight for Your Long Day

, and Isaac continues to write about adjunct issues and more for

The Chronicle of Higher Education

. More or less, what we have are two early 30-somethings with small children working constantly to survive but also thinking of the less fortunate of higher education, whether they're instructors or students. I've already skimmed Isaac's book, and although I'd call most of what I read a nonfictional summary and assessment of how he fought his way out of the adjunct's life to land a full-time tenure-track job at a community college, in this telling, there is plenty of implied advice for adjuncts trying to do the same. Two key points from Isaac's experience are 1) apply early and often, many more jobs than you'd think would be necessary (this rings true as I remember a recent PhD comp/rhet grad applied to more than 100 positions to land one tenure-track job at a four-year school), and 2) also play to your strength during the teaching demonstration. For his TT campus visit, Isaac used a lesson he'd taught many times before, and he nailed it. For many of us, easier said than done, yes, indeed.

Holic's fast-paced novel has an absolutely fantastic cover, and of course, I was excited to see this blurb on the back:

Both writers are full-time teachers now, but both have paid their adjunct dues, and in different ways continue to support the cause of the more tangentially employed among us. For Atticus Review, Nathan has delivered six sets of graphic frames for

Fight for Your Long Day

, and Isaac continues to write about adjunct issues and more for

The Chronicle of Higher Education

. More or less, what we have are two early 30-somethings with small children working constantly to survive but also thinking of the less fortunate of higher education, whether they're instructors or students. I've already skimmed Isaac's book, and although I'd call most of what I read a nonfictional summary and assessment of how he fought his way out of the adjunct's life to land a full-time tenure-track job at a community college, in this telling, there is plenty of implied advice for adjuncts trying to do the same. Two key points from Isaac's experience are 1) apply early and often, many more jobs than you'd think would be necessary (this rings true as I remember a recent PhD comp/rhet grad applied to more than 100 positions to land one tenure-track job at a four-year school), and 2) also play to your strength during the teaching demonstration. For his TT campus visit, Isaac used a lesson he'd taught many times before, and he nailed it. For many of us, easier said than done, yes, indeed.

Both writers are full-time teachers now, but both have paid their adjunct dues, and in different ways continue to support the cause of the more tangentially employed among us. For Atticus Review, Nathan has delivered six sets of graphic frames for

Fight for Your Long Day

, and Isaac continues to write about adjunct issues and more for

The Chronicle of Higher Education

. More or less, what we have are two early 30-somethings with small children working constantly to survive but also thinking of the less fortunate of higher education, whether they're instructors or students. I've already skimmed Isaac's book, and although I'd call most of what I read a nonfictional summary and assessment of how he fought his way out of the adjunct's life to land a full-time tenure-track job at a community college, in this telling, there is plenty of implied advice for adjuncts trying to do the same. Two key points from Isaac's experience are 1) apply early and often, many more jobs than you'd think would be necessary (this rings true as I remember a recent PhD comp/rhet grad applied to more than 100 positions to land one tenure-track job at a four-year school), and 2) also play to your strength during the teaching demonstration. For his TT campus visit, Isaac used a lesson he'd taught many times before, and he nailed it. For many of us, easier said than done, yes, indeed.

Published on July 21, 2013 16:55

July 18, 2013

A Day in the Life

It's possible that my day-in-the-life adjunct's novel is partly the inspiration for Lee Kottner's newish project of encouraging part-time faculty to post their daily lives as blogs.

So far, for contributions, Migrant Intellectual is back after months of archive hibernation, and Brianne Bolin posted a touching one about adjuncting while raising a special-needs child. Both Baum and Bolin focus in part on how the contingent life adversely impacts physical and mental health, and it should be noted you could be part-time and overworking anywhere, not only in academia, to experience these negative impacts.

On a related note, Isaac Sweeney, the publisher of my commencement-angst e-story (it's 35 pages) has his new nonfiction out on his transition from adjunct to full-time community-college faculty. It's called Same Track, Different Track , and here's the mostly memoir's first sentence quoted from the Amazon Book Description:

"I was never supposed to be where I am today. In academia, the route to the tenure track has on it a terminal degree, publications in peer-reviewed journals, and other what-everybody-else-has-done things.”

Bottomline? There's something odd about the America we share in where one adjunct without a terminal degree gets a community-college TT while others with similar qualifications scramble for cash and courses as they cannot even get an annual guarantee of work. Alas, as with houses and cars, our American lives are largely negotiated and navigated on an individual basis; that's what I know to be true.

The whole situation is also a reminder that I have to be grateful for all I have in this world, and highly aware of possible dishonesty if I'm going to claim it's been "earned."

So far, for contributions, Migrant Intellectual is back after months of archive hibernation, and Brianne Bolin posted a touching one about adjuncting while raising a special-needs child. Both Baum and Bolin focus in part on how the contingent life adversely impacts physical and mental health, and it should be noted you could be part-time and overworking anywhere, not only in academia, to experience these negative impacts.

On a related note, Isaac Sweeney, the publisher of my commencement-angst e-story (it's 35 pages) has his new nonfiction out on his transition from adjunct to full-time community-college faculty. It's called Same Track, Different Track , and here's the mostly memoir's first sentence quoted from the Amazon Book Description:

"I was never supposed to be where I am today. In academia, the route to the tenure track has on it a terminal degree, publications in peer-reviewed journals, and other what-everybody-else-has-done things.”

Bottomline? There's something odd about the America we share in where one adjunct without a terminal degree gets a community-college TT while others with similar qualifications scramble for cash and courses as they cannot even get an annual guarantee of work. Alas, as with houses and cars, our American lives are largely negotiated and navigated on an individual basis; that's what I know to be true.

The whole situation is also a reminder that I have to be grateful for all I have in this world, and highly aware of possible dishonesty if I'm going to claim it's been "earned."

Published on July 18, 2013 09:12

July 15, 2013

Fante and Holic

A nice reason to be back in South Carolina is to receive a couple paperbacks in the mail.

I've been a fan of the Fantes, father and son, since finding Dan's Chump Change as a Sun Dog trade paperback years ago, so although the serial-killer angle is a bit beyond my usual, I was excited to open my preordered Point Doom . I'm already 250 pages into it, and so far, the book is a page turner with some good SoCal AA and car-sales grit and satire to it.

Also, workaholic Nathan Holic's American Fraternity Man is due to arrive at my place in a few days, and I'm proud to say that this Greek satire will be the first novel I see with my blurb on the back cover.

I've been a fan of the Fantes, father and son, since finding Dan's Chump Change as a Sun Dog trade paperback years ago, so although the serial-killer angle is a bit beyond my usual, I was excited to open my preordered Point Doom . I'm already 250 pages into it, and so far, the book is a page turner with some good SoCal AA and car-sales grit and satire to it.

Also, workaholic Nathan Holic's American Fraternity Man is due to arrive at my place in a few days, and I'm proud to say that this Greek satire will be the first novel I see with my blurb on the back cover.

Published on July 15, 2013 13:08