Stephen Templin's Blog, page 18

June 23, 2014

SEAL Training 13: For Whom the Bell Tolls

We hadn’t returned the bell to the SEAL instructors, but that was only Round One. We paddled north through the night to Hotel Del Coronado, the resort hotel—we wouldn’t be checking in. Outside the surf zone, we looked to shore for our signal. An instructor flashed our boats the red and green light signals. The first boat crew went in, followed by the others. Then it was my boat crew’s turn.

We hadn’t returned the bell to the SEAL instructors, but that was only Round One. We paddled north through the night to Hotel Del Coronado, the resort hotel—we wouldn’t be checking in. Outside the surf zone, we looked to shore for our signal. An instructor flashed our boats the red and green light signals. The first boat crew went in, followed by the others. Then it was my boat crew’s turn.We caught a good wave going in and paddled hard to stay on it. As we neared the big black boulders, it seemed like waves hit us from three different directions. Our speed kept the water from knocking us around, but we slammed into the rocks hard and fast. Bodies flew out of the boat like Pop-Tarts out of a toaster.

The instructors taught us to never get between the boat and the rocks—which is right where Martinez and I ended up. Our boat stood straight up, the stern jammed down between two boulders. Water had filled the boat. My classmate and I pushed while the others pulled from the other side. It was like trying to move a dead elephant.

The first wave came, sandwiching the two of us between the boulder and the dead elephant. The ocean’s force came so powerfully that all my pushing meant nothing. It knocked the rest of my crew off their feet, smashing them onto the rocks. Someone fell into the ocean. The others who could regain their footing helped pull him out.

Another wave came. I didn’t even try to resist. It pressed the boat against my chest so hard that I knew it would pop.

As the wave receded, our boat leader said, “Pull!”

Martinez and I tried to push the boat off us while our classmates on the other side pulled. Then the wave came again. It squeezed every particle of breath out of me. I could feel my rib cage on the edge of snapping. So this is how I die. Maybe it sounds strange, but I felt calm about dying there.

Instead of fighting the ocean, my classmates braced for the crash—after the wave washed over, they pulled on the boat like madmen. Martinez and I pushed with everything we had—and then some. Finally we broke the boat free. I was so happy to be alive, that I had forgotten all about Hell Week and being cold.

We reached the beach to the greeting of an instructor: “Are you enjoying your vacation?”

“HOOYAH!”

“Drop!”

We did pushups ‘til our arms felt like falling off. A young couple from the Hotel Del had been on the beach for an early morning stroll when they came over to view the festivities. The woman wore a neon orange sweater. Tears streamed down her face. It struck me as ironic—we were the ones who should be crying.

The last boat crew came in. A third of their boat hung deflated, shredded by the rocks. They thought they were finished, but an instructor sent them back out in the ocean again. The next time, they’d come back with only about a third of the boat—this time the crew started to go back out again, but the instructor stopped them.

The instructors didn’t even try to fight us for the bell this time. But the game was far from over…

Published on June 23, 2014 07:06

June 16, 2014

SEAL Training 12: Breakout--No Bell Hell Week

What if we stole the bell during Navy SEAL Hell Week? When a SEAL trainee has had enough, he is supposed to ring a bell when he wants to withdraw from training. More students drop out of training during Hell Week than any other time. But my class was determined not to lose one teammate during the infamous week.

What if we stole the bell during Navy SEAL Hell Week? When a SEAL trainee has had enough, he is supposed to ring a bell when he wants to withdraw from training. More students drop out of training during Hell Week than any other time. But my class was determined not to lose one teammate during the infamous week.One evening, in our barracks, located on the beach of Coronado, California, some of my classmates slept while others remained awake in their beds. In my rack (bed), I slept soundly wearing my BDU's (Battle Dress Uniform) and combat boots. I awoke to the sound of a metal click in the head (restroom). My room was black, except for the sudden flash of an M-60 machine gun coming from the head. The noise assaulted my ears. I saw my classmates crawling out the door, so I crawled out with them.

"Move, move, move!" an instructor yelled.

Outside on the grinder, artillery simulators exploded in the night air: an incoming shriek followed by a boom. Machine guns rattled. A machine pumped a blanket of fog over the ground. Green chemlights decorated the outer perimeter. Water hoses sprayed us. A swarm of instructors yelled at us. An instructor blew his whistle, Tweet. We dove to the ground, crossed our legs, covered our ears with our hands, and opened our mouths. I could smell cordite in the air—I loved the odor—it smelled like show time. This was Breakout, the beginning of Hell Week.

Tweet, tweet. We low-crawled to the sound of the whistle.

Tweet, tweet, tweet. We stood up.

The whistle drills continued between the explosions and the chatter of automatic rifles. Each time the whistle blew twice, we crawled toward the sound, and I could feel the asphalt begin to rub the skin off my knees and elbows. Of the three whistle sounds, I quickly learned to hate tweet, tweet more than one or two whistles. Finally the whistle blew three times and we stood up.

Instructor Blah stood on a platform, calmly speaking into the bullhorn. "GET IN FORMATION!"

We hurried into a formation made up of boat crews.

"ON-YOUR-BACKS-ON-YOUR-FEET-ON-YOUR-STOMACHS!"

The commands were too fast, impossible to follow.

"YOU PEOPLE ARE NOT WORKING TOGETHER! DROP AND PUSH 'EM OUT!"

We did pushups.

"GIVE ME A MUSTER, MR. MARK," Instructor Blah said. The artillery simulators and machine guns filled the air with thunder.

Our class officer, Mr. Mark, said, "Boat Leaders report!"

The members in my boat crew and I counted off and reported to our boat leader. He and the other boat leaders reported to Ensign B, "All present, sir!"

"Any day now, Mr. Mark," Instructor Blah said.

Mr. Mark reported, "All present…"

Instructor Blah raised his eyebrows. "All present?"

"Yes. All present."

"DROP!" Blah said in the megaphone.

We all dropped to the pushup position.

"YOU PEOPLE HAVE GIVEN ME A FALSE MUSTER!" Instructor Blah's voice kept the same monotone. "ONE OF YOUR MEN IS MISSING!"

From the pushup position, Mr. Mark said, "Boat Leaders, give me a muster!"

The explosions and machine gun fire became louder. Maintaining the pushup position, my boat leader walked on his hands to each of us to make sure all of us were present.

One of the other boat crew leaders reported, "Seaman N. is missing, sir!"

Mr. Mark reported, "Seaman Nelson is missing..."

"FIRST YOU TOLD ME, ALL PRESENT! NOW YOU TELL ME, SEAMAN NELSON IS MISSING! WHICH IS IT?"

"Seaman Nelson is missing," Ensign Mark said.

Three instructors brought out Seaman N., took off his blindfold, gag, and plasticuffs. Seaman N. returned to his boat crew.

"They kidnapped me," Seaman Nelson said. In all the noise and confusion of Breakout, no one noticed he was missing.

Instructor Blah calmly said, "NO SEAL HAS EVER BEEN CAPTURED AS A PRISONER OF WAR! BUT YOU LEFT SEAMAN NELSON BEHIND, DIDN'T YOU? PUSH 'EM OUT!"

We did pushups until our arms collapsed. Then we did calisthenics. During the jumping jacks, Senior Chief sprayed a water hose inches from my face, directly up my nose. I counted off as best I could: "One, two, three, one! One, two, three, two!" My words became more and more gargled, and I gagged a couple times. I was happy to be out of the pushup position and happy not to be doing whistle drills, but I hid my emotions: no pain, no joy. Eventually, Senior Chief got bored and moved on to someone else.

Tweet. Prostrated body, crossed legs, covered ears, opened mouths.

Tweet, tweet. Low-crawl.

Tweet, tweet. Low-crawl.

Our bloody knees and bloody elbows crawled across the merciless asphalt. As we neared the beach, I sped up, so I could crawl on the soft sand instead of the black hardtop. When I realized where we were headed—the cold ocean—I slowed down, not in a hurry to get wet. I had to be careful not to go too slow, and receive special attention from the instructors. Stay with the group.

We left the chaotic sounds of instructors shouting, machine guns shooting, and artillery shells exploding behind us. Most of the instructors had faded away. Only a handful remained.

Hell Week had barely begun, and it had already reduced us to our most basic animal instincts for survival. Eventually, we reached the water line crawling on our hands and knees.

A different instructor held the megaphone, "PREPARE FOR SURF TORTURE!"

"HOOYAH!" we said. I don't know where the sudden burst of spirit came from, but it lifted us. We formed a line, facing the instructor, and we locked arms.

"YOU HAVE SOMETHING THAT BELONGS TO THE INSTRUCTORS AND WE WANT IT BACK!"

"HOOYAH!" At that moment, I thought we were more proud than we had ever been as a class since the first day of training. The instructors thought they could break us, but we thought they couldn't. We were in control. We had something they wanted, and they weren't going to get it.

"TAKE THREE STEPS BACKWARDS AND SIT DOWN!"

"HOOYAH!" Our voices shouted out louder than ever. Arms locked, we sat down in frigid water up to our necks, but the water didn't seem so cold. We were fighting back.

"YOU GIVE US THE BELL, AND THE INSTRUCTORS WILL TAKE IT EASIER ON YOU! YOU DON'T GIVE US THE BELL, AND THIS IS GOING TO BE THE WORST HELL WEEK EVER!"

"HOOYAH!" Waves of water crashed over us.

"YOU HAVE STOLEN GOVERNMENT PROPERTY! THAT'S A FEDERAL OFFENSE!"

"HOOYAH!" We smiled. Some of us were laughing. The more the instructor asked for the bell, the more our spirits lifted.

"YOU WILL ALL END UP IN THE BRIG IF YOU DON'T RETURN OUR BELL!"

We sang to the tune of "Take me Out to the Ball Game."

Take me out to the surf zone,

Take me out to the sea,

Make me do pushups and jumping jacks,

I don't care if I never get back,

For it's root, root, root for the SEAL teams,

If we don't pass, it's a shame,

For it's one, two, three rings your out

Of the old BUD/S game!

We yelled: "HOOYAH!"

The instructor stood silent.

Each successive wave hammered us, sapping the warmth from our bodies and push-pulling at our locked arms. Our butts scraped forward and back across broken seashells and rocks.

We started to shiver, and our arms began to weaken.

The instructor said, "IF YOU QUIT NOW, YOU CAN HAVE A BLANKET AND A HOT CUP OF COCOA! WITH MELTED MARSHMALLOWS!"

I retreated into my own private world of cold and pain—the quiet told me that my classmates were doing the same. We shorter guys sat deeper in the water than the others. Petty Officer L., the Ranger veteran of Grenada, who had completed half of Hell Week in an earlier class, shivered more than anyone.

The waves broke our human chain once. Then again. And again and again. Soon most of us were separated. I knew this couldn't go on forever. I knew the instructors carefully calculated the air temperature, water temperature, and wind speed, so they knew the maximum amount of time they could expose us to the cold without killing us.

They wanted their bell, and we weren't going to give it to them. The battle of wills had just begun...

Published on June 16, 2014 06:05

June 9, 2014

SEAL Training 11: From Circus to Medal of Honor

How did a SEAL trainee go from circus to Medal of Honor recipient? In BUD/S training, those of us who couldn’t keep up on a run were gathered up for the greatest show on earth—the circus of pain. The circus performers had to jump into the ocean then roll along the beach—saltwater helps the sand cling to every orifice and crack of the body—rubbing like sandpaper. Each circus performer did calisthenics until every major muscle in their body ached. Some guys left the circus by ringing out (quitting). Some got out by trying harder. But others, even though they gave more than 110% effort, found themselves in the circus after every run because better than their best still wasn’t good enough. While most of the class took a break after finishing on time, the circus played on… I think a lot of guys will agree with me when I say that I have the greatest respect for the circus performers who worked harder than everyone else and somehow managed to finish Hell Week. More than the gazelles running ahead, more than the fish in front, more than the O-Course monkeys, these underdogs were the toughest. One of the most famous of these circus performers was Thomas Norris.

How did a SEAL trainee go from circus to Medal of Honor recipient? In BUD/S training, those of us who couldn’t keep up on a run were gathered up for the greatest show on earth—the circus of pain. The circus performers had to jump into the ocean then roll along the beach—saltwater helps the sand cling to every orifice and crack of the body—rubbing like sandpaper. Each circus performer did calisthenics until every major muscle in their body ached. Some guys left the circus by ringing out (quitting). Some got out by trying harder. But others, even though they gave more than 110% effort, found themselves in the circus after every run because better than their best still wasn’t good enough. While most of the class took a break after finishing on time, the circus played on… I think a lot of guys will agree with me when I say that I have the greatest respect for the circus performers who worked harder than everyone else and somehow managed to finish Hell Week. More than the gazelles running ahead, more than the fish in front, more than the O-Course monkeys, these underdogs were the toughest. One of the most famous of these circus performers was Thomas Norris.Norris wanted to join the FBI, but got drafted instead. He joined the Navy to become a pilot, but his eyesight disqualified him. So he volunteered for SEAL training, where he often fell to the rear on runs and swims—there was talk about firing him. Norris didn’t give up—he became a SEAL.

In Vietnam, 1972, two pilots of a surveillance aircraft went down deep in enemy territory where over 30,000 NVA (North Vietnamese Army) prepared for an Easter offensive. In the most expensive rescue attempt of the Vietnam War, 14 people were killed, eight aircraft downed, two rescuers captured, and two more rescuers stranded in enemy territory. The air rescue became impossible. Lieutenant Norris led a five-man Vietnamese SEAL patrol and located one of the pilots, returning him to the FOB (Forward Operating Base). The NVA retaliated with a rocket attack on the FOB, killing two of the Vietnamese SEALs and others.

Norris and his three remaining Vietnamese SEALs failed once to rescue the second pilot. Because of the impossibility of the situation, two Vietnamese SEALs worried about their lives for another rescue attempt. Norris decided to take Vietnamese SEAL, Nguyen Van Kiet, to make another attempt—failing.

On April 12th, about 10 days after the plane had been shot down, Norris got a report of the pilot’s location. He and Kiet disguised themselves as fishermen and paddled their sampan upriver into the foggy night. They located the pilot at dawn on the river bank hidden under vegetation, helped him into their sampan, and covered him with bamboo and banana leaves. A group of enemy on the land spotted them but couldn’t get through the thick jungle as fast as Norris’ team could paddle on the water. When they arrived near the FOB, an NVA patrol spotted the rescuers and poured heavy machine gun fire down on them. Norris called in an air strike to keep the enemy’s heads down. And a smoke screen to blind them. Norris and Kiet took the pilot into the FOB where Norris gave him first aid until he was evacuated. Lieutenant Thomas Norris received the Medal of Honor. Kiet received the Navy Cross, the highest award given to a foreign national.

About six months after Norris rescued a pilot in Vietnam, he faced the jaws of adversity again. Lieutenant Norris chose Petty Officer Michael Thornton for a mission. Thornton selected two Vietnamese SEALs: Dang and Quan. And one shaky Vietnamese officer was assigned to the team. Carrying AK-47’s and lots of bullets, they rode a South Vietnamese Navy junk (U.S. Navy ships were unavailable) up the South China Sea, launched a rubber boat from the junk, and then patrolled on land to gather intelligence. The junk had inserted them too far north. Norris walked the point with Thornton on rear security and the Vietnamese SEALs between them. During their patrol, they realized they were in North Vietnam. While hiding in their day layup position, the Vietnamese SEAL officer, without consulting Norris or Thornton, ordered the two Vietnamese SEALs to do a poorly designed prisoner snatch on a two-man patrol, alerting the enemy to their presence.

Thornton knocked out one of the enemy patrol with his rifle butt, so he couldn’t alert the nearby village. But the other enemy escaped alerting about 50 to 75 NVA (North Vietnamese Army). Thornton said, “We got trouble.” The SEALs bound the knocked out enemy then when he became conscious, Dang interrogated him.

Norris and Dang shot the enemy. Norris used the radio on Dang’s back to call for naval gunfire support: coordinates, positions, types of rounds needed… The Navy operator on the other end (his ship under enemy fire) seemed new at his job, unfamiliar with fire support for ground troops. Norris put down the phone to shoot more enemy. When he got back on the radio, his call had been transferred to another ship, under enemy fire and unable to help. Norris and Quan moved back while firing at the enemy.

Thornton put the Vietnamese lieutenant on the rear while he and Quan defended the flanks. Thornton shot several NVA, took cover, rose in a different position, and shot more enemy. Although Thornton knew the enemy popped up from the same spot each time, they didn’t know where Thornton would pop up from or how many people were with him. While maneuvering back, he shot through the sand dune, hitting the heads hiding in the same positions where they ducked.

After about five hours of fighting, Norris connected with a ship that could help: Newport News.

The enemy threw a Chicom (Chinese communist) grenade at Thornton. Thornton threw it back. The enemy threw it again. Thornton threw it back. When the grenade came back the fifth time, Thornton dove for cover. The grenade exploded. Six pieces of shrapnel struck Thornton’s back. He heard Norris call to him, “Mike, buddy, Mike, buddy!” But Thornton stayed quiet. About four enemy ran over Thornton’s position—he shot all four. Two fell on top of him and the other two fell backwards. Up to that point, he had taken out about 33 enemy. “I’m all right!” Thornton called. “It’s just shrapnel.”

The enemy became quiet. Now they had the 283rd NVA battalion helping them outflank the SEALs.

The SEALs began to leapfrog. Norris laid down cover fire so Thornton, Quan, and Tai could retreat. Then Thornton and Dang would do the same while Norris and his team moved back. Norris brought up a LAW rocket to shoot when an NVA shot him in the face with an AK-47, knocking him off a sand dune. Norris tried to get up to return fire but passed out.

Dang ran back to Thornton. Two rounds hit the radio Dang carried on his back.

“Where’s Tommy?” Thornton asked.

“He’s dead.”

“Are you sure?”

“He got shot in the head.”

“Are you sure?”

“I saw him when he fell.”

“Stay here. I’ll go back and get Tommy.”

“No, Mike. He’s dead. They’re all coming.”

“Y’all stay here.”

Thornton ran about 500 yards to Norris’ position through a hail of enemy fire. He killed several NVA getting next to Norris’ body. The bullet had entered the side of Norris’ fhead, and blown out the front of his forehead. Thornton thought his buddy was dead. He threw his body on his shoulders in a fireman’s carry and grabbed Norris’ AK. Thornton had already used up eight grenades, his LAW rockets, and was down to one or two magazines of ammo.

Suddenly, the first round from the Newport News came in like a mini Volkswagen flying through the air. When it exploded, it threw Thornton down a 20-30 foot dune. Norris’ body flew over Thornton. If he wasn’t dead, he’s dead now, for sure. Thornton got up and went to pick up Thornton.

“Mike, buddy,” Thornton said.

“The SOB’s alive.”

Thornton picked him up, put him on his shoulders, and took off running. Dang and Quan gave cover fire.

The Navy artillery round had bought them some time, but the time was up. Enemy rounds came at the SEALs again.

Thornton reached Dang and Quan’s position. “Where’s Tai?”

When Thornton went back to get Norris, the Vietnamese lieutenant, Tai, had disappeared into the water.

“When I yell one, Quan I want you to lay down a base of fire,” Thornton said. “When I yell two, Dang you lay down a base of fire. Three, I’ll lay down a base of fire. And we’ll leapfrog back to the water.”

As they got to the water’s edge, Thornton fell. He didn’t know at the time, he’d been shot through his left calf. He picked up Norris and carried him under his arm. In the water, he felt a floundering movement—he had Norris’ head under the water. Thornton got his buddy’s head above water. Norris’ life vest was tied to his leg, SOP (Standard Operating Procedure) for Team 2 SEALs, so Thornton put his vest on Norris, using it to keep both of them afloat.

Quan fluttered in the water, the right side of his hip shot off. Thornton grabbed him, and Quan hung onto Norris’ life preserver. Kicking out to sea, Thornton could see bullets travelling through the water: Good Lord, don’t let any of those hit me.

“Do we got everybody?” Norris asked. He could see Quan and Dang but not the officer. Pushing down on Thornton, he saw Tai, far out to sea. Norris blacked out, again.

After swimming well out of the enemy’s range of fire, Thornton and the two Vietnamese SEALs saw the Newport News leave. With bodies scattered over the ground, the ship thought the SEALs were dead.

Quan and Dang asked, “What do we do, now?”

“Swim south,” Thornton said. He put two 4X4 battle dresses on Norris’ head, but they couldn’t cover all of the wound. Norris was going into shock.

Other SEALs, in a junk searching for their buddies, found Tai and debriefed him. Then they found Norris, Thornton, Dang, and Quan. Thornton radioed the Newport News for pickup.

Onboard the Newport News, Thornton carried Norris to medical. The medical team cleaned up Norris as best they could, but the doctor said, “He’s never going to make it.”

Norris was medevaced to Da Nang. From there, they flew him to the Philippines.

For Thornton’s actions, he received the Medal of Honor.

Norris survived, proving the doctor wrong. He was transferred to the Bethesda, Maryland Naval Hospital. After years of major surgeries, he had lost part of his skull and his eye.

The Navy retired Norris, but the only easy day was yesterday. Norris returned to his childhood dream: becoming an FBI agent. In 1979, he requested a disability waiver. FBI Director William Webster said, “If you can pass the same test as anybody else applying for this organization, I will waiver your disabilities.” Of course, Norris passed.

In the FBI, Norris tried to become a member of the FBI’s newly forming Hostage Rescue Team (HRT). But the FBI’s bean counters and pencil pushers didn’t want to allow a one-eyed man on the HRT. HRT founder, Danny Coulson, said, “We’ll probably have to take another Congressional Medal of Honor winner with one eye if he applies. But I’ll take the risk.” Norris became an assault team leader. After 20 years with the FBI, he retired.

Notes: Medal of Honor info from Pritzker Military Library: (Danny Coulson quote from his book, No Heroes.)

Published on June 09, 2014 01:14

June 7, 2014

June 2, 2014

SEAL Training 9: Drownproofing

I’d always thought drowning is one of the worst ways to die. The sun lay buried in the horizon, as my class marched double-time through the Naval Amphibious Base at Coronado, California. Wearing the same camouflage uniforms, all of us sang out in cadence looking confident, but the song of our voices was hollow.

I’d always thought drowning is one of the worst ways to die. The sun lay buried in the horizon, as my class marched double-time through the Naval Amphibious Base at Coronado, California. Wearing the same camouflage uniforms, all of us sang out in cadence looking confident, but the song of our voices was hollow.Wake up, wake up, N.A.B.

We’ve been up since half past three

Runnin’, swimmin’ all day long

That’s what makes a tadpole strong

Whooyah hey, runnin’ day

Whooyah hey, easy day

Our anxieties manifested themselves as lingering mists from our warm breath hitting the winter air. The noise of our combat boots struck the black asphalt with melancholy.

Most of the men in my Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) class were about 21 years old—I was only 19. Together we were a smorgasbord of life: Egyptian army officer, MIT graduate, surfer punk, etc. Each of us had different reasons for becoming Navy SEALs: show patriotism, become king of the surfers, etc. But on that cool winter’s morning, we all had one thing in common: dread.

We arrived at the pool located at Building 164 and stripped down to our UDT swim shorts. The SEAL instructors watched us with shark eyes. We grouped ourselves in pairs with our swim buddies.

My swim buddy asked, “Do you want to go first or should I?”

“I want to get this over with,” I said.

We stood at the deep end of the pool. Goose bumps pricked our flesh as each of our partners tied us up with high strength cord. My partner tied my feet together.

“Tie it good,” I said. “I don’t want to have to do this twice.”

After finishing the knot, he proceeded to tie my hands behind my back.

Stoneclam wore his khaki UDT (Underwater Demolition Team) shorts and a dark blue t-shirt. The t-shirt had a thin yellowish-gold border on the sleeves. Two cartoon-like figures were on the left breast: a frog holding a burning stick of dynamite in its hand and a seal carrying a knife in its mouth. Written in small, yellowish-gold letters were the words: UDT/SEAL Instructor. Kneeling down on one knee, he touched the water reverently as if to consecrate it for us. He climbed up to the lifeguard chair and took his ritualistic position. “You are all going to love this. Drown-proofing is one of my favorites. Sink or swim, sweet peas.”

Half of my class stood at the edge of the deep end with our feet tied together and hands tied behind our backs. Our swim-buddies stood behind us. Instructors were joking, but it was all a peripheral blur to me.

I can’t let them get inside my head. Focused on calming my respiration and heartbeat.

Instructor Stoneclam said, “When I give the command, the bound men will hop into the deep end of the pool. You must bob up and down twenty times, float for five minutes, swim to the shallow end of the pool, turn around without touching the bottom, swim back to the deep end, do a forward and backward somersault underwater, and retrieve a face mask from the bottom of the pool.

“If your ropes come undone, you must start over from the beginning. If your ropes come undone a second time, you fail. If you break your ropes, you pass—but don’t try it. I only know of one student who ever broke his ropes. We’ll be watching you to make sure no one cheats.”

Standing on the edge of the pool, I should have realized how abnormal all this was. Just doing all that bobbing and swimming and somersaults without my hands and feet tied would be hard enough. My mind focused on how peaceful the water was. My breathing and heart rate slowed.

Instructor Stoneclam’s dark eyes probed us. “First group, enter the water.”

The smooth surface of the water broke as we jumped in. A flurry of thoughts assaulted me: panicking, suffocating, drowning. Block the negative. Be calm. Avoid the negative. The heated pool is warm. Focus on the warmth. Become one with the water. My classmates and rose and sank at different heights and depths. Some touched the bottom and were already rising to the surface. A negative thought wrestled with me: the guys at the top are going to breathe while I’m still down here. I waited helplessly for my feet to touch the bottom. Wait for the breath. Slow it down. Control the rhythm. I imagined soft ballet music. My toes touched the concrete bottom. Don’t shoot out of the water like a missile and draw the attention of the instructors. I gently pushed off. I wanted air, but I couldn’t think about it. My head cleared the surface. I heard screams and saw splashing on the other side of the pool. I closed my eyes and filled my ears with ballet music. My mouth formed a tight circle, sucking a bite of oxygen straight to my lungs.

I sank slowly to the bottom. The instructors can’t touch me here. The water is my haven. Pushing off from the bottom again, I opened my eyes and continued to imagine ballet music as my classmates and I continued to rise and fall in our new haven. The Egyptian officer smiled, looking like a brown, oversized water lily. Priest, the surf-punk, made a goofy face at me and wiggled his body like some sort of wacky water worm as he rose upward. I smiled, bobbing up and down in the water wearing my pink tutu.

On one of my trips to the surface, I looked over to the commotion at the other side of the pool. One of my classmates thrashed the water trying to get to the edge of the pool. “Help me, I’m drowning! Ahggh!”

Instructor Stoneclam used the lifesaving pole to push him away from the edge, “If you were drowning, you wouldn’t be telling me about it.”

The panicked guy bit the pole.

I got my bite of air and sank down. When I came back up, the panicked student was being helped out of the pool—he had enough of training.

After bobbing, I floated for five minutes. Next, I began my dolphin kick along the length of the pool. Keep it slow. Keep the rhythm. I kicked then turned my head to breathe—side-stroke style. Kick-and-breathe, kick-and-breathe. I reached the shallow end of the pool and began making a dolphin-turn right. Parsons was turning left, aimed for a head-on collision course with me. If either of us touched the bottom of the pool, we’d fail. I became anxious and started to lose my rhythm. Parsons dove underneath me as we made our turn. Our bodies scraped each other, but neither of us touched the bottom of the pool. I became more anxious.

I dolphined my way back to the deep end. There I bobbed once. I did my forward somersault. I still hadn’t recovered my breathing rhythm after the near-collision with Priest. Most of my classmates had already finished their forward and backward somersaults. Nineteen face masks lay on the bottom of the pool. One-by-one the masks disappeared as each of my buddies grabbed a mask with their teeth and rose to the surface, completing their job. I was the last one in the pool. I could feel Instructor Stoneclam’s eyes on me.

I did the backward somersault. My breathing and movement became uncoordinated. The threat of failure attacked me. My chlorine-saturated eyes frantically searched the blurry bottom for a face mask. I spotted one mask on the bottom at the far end of the pool. I can’t make it that far. Suddenly, my blurred vision caught sight of a mask down to my left. My feet touched the bottom—my toes only inches away. I dropped to my knees. I tried to lean over to grab the mask with my teeth. But I had swallowed too much air during my somersaults, and my body floated up before I could bite the mask. My body stopped halfway up. There was no air in my lungs to float me to the top and too much air in my stomach to allow me to sink to the bottom. The taste of chlorine made me want to vomit.

Fear stepped aside to let discouragement make its entrance. Discouragement was infinitely more powerful than fear. I felt myself shrinking. I heard voices—my classmates cheering me on. They seemed so far away. I was too weak. I failed. Discouragement smashed me, destroying every particle of human energy from me. The hammer of discouragement rose high in the air, preparing to make its final blow. But I didn’t want it to end this way. I didn’t want to fail.

I started to get angry. Angry at fear and discouragement. Angry at Instructor Stoneclam. Angry at anything that would get in my way from succeeding—including myself. My spirit exploded. Its heat and power rumbled through me. The shockwave overwhelmed my senses.

My feet kicked rapidly, propelling me upward. I surfaced with half of my body shooting out of the water. I flipped like an angry fish and dove head first into the water, frantically kicking my tied feet.

I shot down at the mask, and my forehead smashed into the floor, stopping me. I twisted my head around and clenched the black strap with my teeth. I kicked and wiggled without oxygen, managing to move head-first toward the top. My head felt so dizzy.

Complete the mission. I struggled halfway to the surface. My body was heavy. My peripheral vision became grey. I kicked harder. Every part of me craved oxygen as the grey circle around my vision became smaller, darker. My body started to tingle. I felt like I was losing consciousness—getting harder and harder to focus on anything.

I managed to poke my head out of the water. Madly, my feet kept kicking. Some classmates started to applaud.

“Shut up!” Instructor Stoneclam barked.

I refused to stop kicking unless Stoneclam told my swim buddy to help me out, and I refused to let go of the mask. Instructor Stoneclam studied me leisurely. I sucked air and water through my teeth. I figured he could either let my buddy help me out from the pool, or Stoneclam could rescue me when I became unconscious and sank to the bottom. Either way, I wasn’t going to let go of the mask.

Instructor Stoneclam told my swim buddy, “Pull him out.”

I felt incredible relief as my partner and another student pulled me out. The ground felt strange, and I had to sit down because my legs didn’t support me well. My classmates untied my hands. I felt like a fish, not knowing what to do with my hands except flap the kinks out of my wrists. My head ached. Steam rolled off my wet body.

An instructor told me, “I’ve never seen anyone pull their mask out like that. You’ll have to explain your technique.”

The other instructors smiled.

Instructor Stoneclam barked, “Next!”

I helped tie my swim buddy’s feet and hands.

“Second group, enter the water,” Instructor Stoneclam said.

I no longer thought drowning was one of the worst ways to die. Drownproofing replaced my old fear with a new one: failure without trying everything I can do to succeed.

Published on June 02, 2014 11:20

May 21, 2014

SEAL Team Six vs. Delta Force: Running and Gunning

When SEAL Team Six operators run with a rifle, they're often running "muzzle up." In contrast, Delta operators usually run "muzzle down." Which is better? In the next two videos, Kyle Defoor (SEAL Team Six) and Paul Howe (Delta Force) discuss their views:

I've used both techniques, and environmental awareness is critical: don't aim at anything you don't wish to destroy/kill. If I'm loading onto a boat, I don't want to put a hole in the deck. Likewise, if I'm loading onto a helo, I don't want to put a hole in a main rotor blade. Both muzzle up and muzzle down can be used to run fast as is seen with Defoor's example above and Pat McNamara's (Delta) example below:

SEALs have been using "muzzle up" since Vietnam:

Even so, Vietnam SEALs also used muzzle down. Another important factor to consider is training: follow the rules of the instructor/range. If the instructor is a SEAL, muzzle up will probably be allowed more, but if the instructor is a Delta operator, he'll probably expect much of your movement to be with the muzzle down. When in Rome, don't piss off your instructor. In summary, situational awareness and safety are key in deciding whether to go muzzle up or muzzle down.

Even so, Vietnam SEALs also used muzzle down. Another important factor to consider is training: follow the rules of the instructor/range. If the instructor is a SEAL, muzzle up will probably be allowed more, but if the instructor is a Delta operator, he'll probably expect much of your movement to be with the muzzle down. When in Rome, don't piss off your instructor. In summary, situational awareness and safety are key in deciding whether to go muzzle up or muzzle down.

P.S. Dalton Fury (Delta) was kind enough to add Kyle Lamb's (Delta) remarks to the discussion, so I posted the video here while I try to figure out how to enable links in the Comments:

I've used both techniques, and environmental awareness is critical: don't aim at anything you don't wish to destroy/kill. If I'm loading onto a boat, I don't want to put a hole in the deck. Likewise, if I'm loading onto a helo, I don't want to put a hole in a main rotor blade. Both muzzle up and muzzle down can be used to run fast as is seen with Defoor's example above and Pat McNamara's (Delta) example below:

SEALs have been using "muzzle up" since Vietnam:

Even so, Vietnam SEALs also used muzzle down. Another important factor to consider is training: follow the rules of the instructor/range. If the instructor is a SEAL, muzzle up will probably be allowed more, but if the instructor is a Delta operator, he'll probably expect much of your movement to be with the muzzle down. When in Rome, don't piss off your instructor. In summary, situational awareness and safety are key in deciding whether to go muzzle up or muzzle down.

Even so, Vietnam SEALs also used muzzle down. Another important factor to consider is training: follow the rules of the instructor/range. If the instructor is a SEAL, muzzle up will probably be allowed more, but if the instructor is a Delta operator, he'll probably expect much of your movement to be with the muzzle down. When in Rome, don't piss off your instructor. In summary, situational awareness and safety are key in deciding whether to go muzzle up or muzzle down.P.S. Dalton Fury (Delta) was kind enough to add Kyle Lamb's (Delta) remarks to the discussion, so I posted the video here while I try to figure out how to enable links in the Comments:

Published on May 21, 2014 10:27

May 19, 2014

SEAL Training 8: Surf Passage

In a classroom at the Naval Special Warfare Center, Instructor Stoneclam stood next to a 13-foot long, black, rubber boat resting on the floor in front of my class.

In a classroom at the Naval Special Warfare Center, Instructor Stoneclam stood next to a 13-foot long, black, rubber boat resting on the floor in front of my class.“Today, I’m going to brief you on Surf Passage. This is the IBS. Some people call it the Itty-Bitty Ship, and you’ll probably have your own pet names to give it, but the Navy calls it the Inflatable Boat, Small. You will man it with six to eight men who are about the same height. These men will be your boat crew.”

He drew a primitive picture on the board of the beach, ocean, and stickmen scattered around the IBS. He pointed to the stickmen scattered in the ocean.

“This is you guys after a wave has just wiped you out.”

He drew a stickman on the beach.

“This is one of you after the ocean spit you out. And guess what? The next thing the ocean is going to spit out is the boat.”

Instructor Stoneclam used his eraser like a boat.

“But now the 170-pound IBS is full of water and weighs about as much as a small car. And it’s coming right at you here on the beach. What are you going to do? If you’re standing in the road, and a small car comes speeding at you, what are you going to do? Try to outrun it? Of course not. You’re going to get out of the road. Same thing when the boat comes speeding at you. You’re going to get out of the path it’s traveling. Run parallel to the beach.

“Some of you look sleepy. All of you drop and push ‘em out!”

Later, the sunshine dimmed as we stood by our boats facing the ocean. Bulky orange kapok life jackets covered our Battle Dress Uniforms (BDU’s). We tied our hats to the top button hole on our shirt collars with orange cord. Each of us held our paddles like rifles at the order-arms position, waiting for our boat leader to return from where the instructors briefed him and the other boat crew leaders. Our group was the “Smurf Crew”—the boat with the shortest men.

Our boat leader quickly returned and gave us orders. With boat handle in one hand and paddle in the other hand, we raced with our boat into the water. The other boat crews raced too.

“One’s in!” our boat leader called.

Our two front men jumped into the boat and started paddling. I ran in water almost up to my knees.

“Two’s in!”

Martinez and I jumped in and started paddling.

“Three’s in!”

The third pair jumped in and paddled, followed by our boat leader, who used his oar at the stern to steer.

“Stroke, stroke!”

I dug my paddle in deep and pulled back as hard as I could. I glanced over at another boat where the Egyptian officer, had a big smile on his face like he was on the Catalina cruise. His paddle leisurely slapped the top of the water.

In front of us, a seven-foot wave formed.

“Dig, dig, dig!”

Our boat climbed up the face of the wave. I saw one of the boats clear the tip. We weren’t so lucky. The wave picked us up and slammed us down, sandwiching us between our boat and the water. As the ocean swallowed us, I swallowed a mouthful of boots, paddles, and cold saltwater.

Eventually, the ocean spit us onto the beach along with most of the other boat crews. The instructors greeted us by dropping us. With our boots on the boats, hands in the sand, and gravity against us, we did pushups.

Then we gathered ourselves together and went at it again—with more motivation and better teamwork. This time, we cleared the breakers.

Back on shore, a boyish-faced trainee from another boat crew, picked his paddle up off the beach. As he turned around to face the ocean, a boat raced toward him sideways.

Instructor Stoneclam shouted in the megaphone,

“GET OUT OF THERE!”

Boy-Face ran away from the boat, just like the instructors told us not to. Fear has a way of turning Einsteins into amoebas.

“RUN PARALLEL TO THE BEACH! RUN PARALLEL TO THE BEACH!”

Boy-Face continued to try to outrun the speeding vehicle. The boat came out of the water and slid sideways like a hovercraft over the hard wet sand. When it ran out of hard wet sand, its momentum carried it over the soft dry sand until it hacked Boy-Face down. Instructor Stoneclam, other instructors, and the ambulance rushed to the wounded man.

Doc, one of the SEAL instructors, started first aid. I never heard Boy-Face call out in pain. The boat broke both his legs at the thigh bones.

When the day finished, we hit the hot showers, but Parsons, the punker with Billy Idol hair, grabbed his surfboard and headed back for more:

“Those waves are thrashin’!”

Published on May 19, 2014 05:11

May 14, 2014

Russian Intervention in Ukraine: Interview with Stephen Templin

Published on May 14, 2014 10:42

May 12, 2014

SEAL Training 7: Super Marios

Like Mario, you can hit the O-Course running, jumping, and ducking, but unlike Mario, you will feel pain.

Like Mario, you can hit the O-Course running, jumping, and ducking, but unlike Mario, you will feel pain.The sun shone brightly as we stood in formation on the beach south of our barracks at the obstacle course—affectionately known as the O-Course. A SEAL instructor explained,

“Some night you might have to lock out of a submarine, hang on to your dear life as your Zodiac jumps over waves, scale a cliff, hump through enemy territory to your objective, scale a three-story building, do your business, and get out. The O-Course is going to help you do all that.

“Remember that when you get to the Slide for Life, if you think you’re going to fall, hang on to the rope with your hands. Let go of your feet first, then release your hands and fall. Doc is here, but don’t expect him to put Humpty Dumpty back together if you land on your back and paralyze yourself.”

After the instructor demonstrated the whole course at full speed, we lined up in alphabetical order of our last names. I started near the end: “T” for Templin. When my turn came, I took off like a chimp with hemorrhoids. The most important strategy I used was my legs, reserving my arms for balance, whenever possible. The thighs are the biggest muscles in the body, so it pays to use them.

Toward the end of the Parallel Bars I used my arms to spring me high and forward then slapped the end of the bars as I came down, saving a fraction of a second.

Next, I ran full speed at the Low Wall—twelve feet was considered low. Still running, I leaped up and landed my right foot on a stump. I jumped from the stump like Mario in a Nintendo video game. I caught the top of the wall with my stomach, and my momentum carried me over the other side.

Sprinting to the High Wall, I climbed the rope. The guy next to me tried to climb his rope straight up, but he lost his footing and fell back down. I kept my body low and perpendicular to the wall, passing him.

Then I belly-crawled under the Barbed Wire, passing another classmate.

After the crawl was the sixty-foot Cargo Net. I pumped my legs, using them to step up the horizontal ropes while I used my hands on one of the vertical ropes to guide me up. The net to the far right and far left was closer to the poles suspending it, making the rope more firm and easier to climb. As I approached the top rail of the Cargo Net, I reached over top and down to the rope on the other side, where I grabbed a handful of rope. I flipped myself over to the other side—at about sixty-feet above the ground, it was far from the safest technique, but it was the fastest. Going down, I used my arms like a gorilla. I grabbed the lowest horizontal rope I could reach with one hand then dropped down while my other hand reached for the next lowest place I could grab. I passed another classmate.

Next, I steadied myself over the Balance Logs, being careful not to fall off and have to repeat the logs from start. One of my classmates fell off and started over as I passed him.

I double-timed over the pyramid of logs called the Hooyah Logs.

After that, I ran to the Rope Transfer. I grabbed up as high on the rope climb as I could, lifted my legs up to a squatting position. I wrapped the rope around my right leg, beginning from between my thighs, crossing over the back of my calf, coming around the outside of my ankle, and laying the rope across the top of my right boot. With my left boot, I stepped on top of the rope, clamping it between the bottom of my left boot and the top of my right boot. I stood until my hands grabbed high on the rope. Then I loosened the rope on my right leg. Again, I raised my legs to a squatting position. Then I wrapped the rope around my right leg and stood up. I continued up the rope like an inchworm to the top. It wasn’t a fast technique, but it conserved arm energy. At the top, I reached across to the second rope then slid down it. My right leg wrapped the rope to slow my decent and save me from a crash-burn into the ground.

The Dirty Name deserved its reputation. The horizontal logs were spaced at devious intervals. I jumped from one horizontal log to the higher horizontal log in front of me. I almost jumped too high and too far, nearly clearing the log and falling headfirst into the sand. Then I jumped to the next horizontal log in front of me. I jumped high enough, but my jump almost wasn’t far enough. I managed to wiggle over the top and drop down on the other side.

I double-timed over another pyramid of Hooyah Logs.

Next I hit the Weaver. Like a human thread, I sewed myself in and out of a series of sloped parallel pipes.

Then I climbed a rope about twelve feet up to the Burma Bridge—using my legs more than my arms. I quickly walked across the seventy-five-foot rope bridge, and lowered myself down the rope on the other end.

Next, I ran to the bottom of a three-story tower. At the top, a rope stretched about one hundred-feet across to low bar. There were no ropes or ladders to climb up the three-story tower. Like my classmates, I had to jump up and grab the ledge to the second level then swing my legs up—repeating the process up to the third level. From the top, I climbed across the hundred-foot rope: the Slide for Life. I started using the commando style, pulling myself across the top of the rope while my body faced down, but I lost my balance and ended up under the rope staring up at the sky—fortunately my hands and feet were still attached to the rope. My banana style used up more of my arm strength than the commando style, but at that point I was more worried about finishing with any technique I could before I fell off and broke my neck.

One of my classmates, I think it was Petty Officer Tee, behind me wasn’t so lucky. He had used up his arm strength on many of the obstacles. He got stuck, banana style, crossing the Slide for Life rope.

“Feet first!” Doc yelled. “Fall feet first!”

But Tee had no energy in his arms to do anything except lock them onto the rope and hope that he didn’t die. Soon his arm-lock broke, and he fell about six feet. His Alien-shaped head landed in the sand with his feet almost straight up in the air. His body fizzled to the earth.

Doc sprinted to him. The olive drab green 4WD medical truck arrived behind Doc. Tee stood up and brushed the sand out of his hair. He looked more embarrassed than hurt.

Chief Geronimo said, “Sit down.”

Tee sat.

Doc looked into Tee’s eyes. “What is your name?”

“Petty Officer Tee.”

“Where are you?”

“The O-Course.”

An instructor brought out the litter, a basket-like stretcher.

“You seem okay, but we’re going to have Medical take a look at you to make sure,” Doc said.

The instructors strapped Tee into the litter, loaded him in the ambulance, and took him away. Later, we found out he was OK.

And I set the class record for the O-Course.

Published on May 12, 2014 05:18

May 5, 2014

SEAL Training 6: Rockets' Red Glare

On another morning, about 0500 behind our barracks, we stood on the beach in formation waiting to begin Physical Training (PT). It was too dark to see the ocean behind us, but we could hear the waves. Outdoor lights illuminated our barracks and the Naval Special Warfare Center in front of us. We sang the Star-Spangled Banner. I thought we did a pretty good job of singing off key and forgetting the words, but Martinez, Duquez, and our two Egyptian officers just destroyed it. The four foreign guys tried their best, but it only got worse. Some in our class started snickering.

On another morning, about 0500 behind our barracks, we stood on the beach in formation waiting to begin Physical Training (PT). It was too dark to see the ocean behind us, but we could hear the waves. Outdoor lights illuminated our barracks and the Naval Special Warfare Center in front of us. We sang the Star-Spangled Banner. I thought we did a pretty good job of singing off key and forgetting the words, but Martinez, Duquez, and our two Egyptian officers just destroyed it. The four foreign guys tried their best, but it only got worse. Some in our class started snickering.Suddenly, I heard a thunk from behind and a classmate came flying forward like he’d been shot out of an artillery cannon. He crashed into the guy in front of him and the two of them tumbled to the sand.

A voice came out from the dark behind us. “What is so funny about the Star-Spangled Banner?”

Ensign Mark shouted, “Instructor Stoneclam!”

Instructor Stoneclam cut us off, “Shut up and drop!”

We dropped to the pushup position in silence. I thought the days of military instructors hitting trainees were over, but I thought wrong. Now I was nervous. Not the kind of nervous like waiting to be attacked by a street thug in the dark—more the kind of scared like waiting to be attacked by a Navy SEAL in the dark.

Instructor Stoneclam marched to the front of our formation and faced us. His eyes were on fire. “I want to know what is funny about the ‘Star-Spangled Banner!’ Is it the bombs bursting in air? Rockets’ red glare?”

No answer.

“Is the flag funny? I want to know what is so damn funny about our national anthem!”

“Nothing is funny about the national anthem, Instructor Stoneclam,” Ensign Mark said.

Instructor Stoneclam said, “You got that right. Push ‘em out!”

After we finished the first set of 20 pushups, we stopped in the up position, a.k.a. front leaning rest, waiting for permission to recover.

“Push ‘em out!”

Over one hundred pushups later, our arms and legs trembled. Our sagging bodies strained to stay off the ground.

“Get wet and sandy!”

We sprinted to the ocean, dove in, hurried out of the water, and rolled ourselves in the soft sand until we became sugar cookies. Somehow the sand found its way into my eyes, ears, nose, mouth and crack of my ass. The sand may have looked like sugar, but it didn’t taste like sugar. And the sand didn’t dissolve like sugar when it got wet. It rubbed like sandpaper.

“Full jumping jacks. Ready, begin.”

Our class sounded off: “ONE, TWO, THREE, FOUR—ONE. ONE, TWO, THREE, FOUR—TWO…”

Instructor Stoneclam did the PT with us.

BUD/S Indoc PT

Exercise Count Reps

Full jumping jacks 4 20

Half jumping jacks 2 20

Trunk twisters sitting 4 8

Trunk side stretch 4 8

Pushups 2 10

Hi-jack/Hi-Jill 4 8

Pushups 2 10

Press-press fling 4 8

Triceps pushups 2 6

Wind mills 4 10

Dive bomber pushups 2 6

Up back and over 4 6

Wind mills 2 10

Pushups 2 10

Swimmer stretch 2 4

Trunk bend fore & aft 4 6

Pushups 2 10

Sit ups 2 25

Leg levers 2 10

Trunk rotations 4 6

Pushups 2 10

Sitting twisters 4 6 a.k.a. sitting bicycles

Sitting knee bends 4 6

Hands & toe sit ups 2 6

Trunk bend fore & aft 4 6

Back flutter kicks 4 30

Good morning darlings 2 30 a.k.a. scissors

Neck rotations 4 8

Triceps pushups 2 6

Cherry pickers 4 6

Trunk twister stretcher 4 6

Sitting flutter kicks 4 6

Stomach pump ups 2 20

Back rollers 2 8

Trunk rotations 4 6

Chase the rabbit 4 8

Dive bomber pushups 2 6

Stomach flutter kicks 30 sec. 1 a.k.a. arm haulers

Standing head to knee 2 6

Standing calf stretch 2 6 (rise up on toes)

Stand hamstring stretch 2 6 stand knee to chest

Standing groin stretch 4 6 a.k.a. groin stretch

Sitting head to knee 2 6

Sitting back benders 2 6 a.k.a. hurdler

Sitting calf stretch 2 6

Sitting hurdler stretch 2 6

Butterfly 15 sec. 2

Sitting thigh stretch 2 6 sit w/legs spread & reach forward

Sit hamstring stretch 2 6 a.k.a. Ilio tibial band stretch

Body builders 8 8

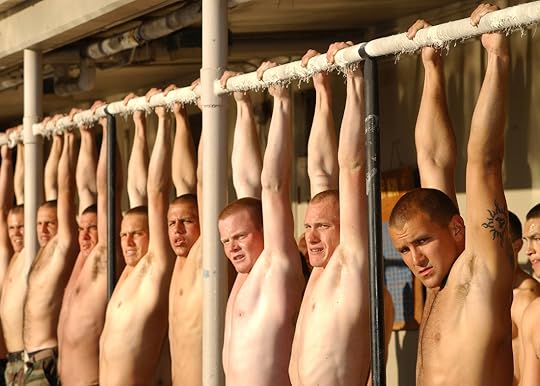

Pull ups 2 6

Dips 2 8

When we finished, my arms felt like jelly-fish. None of us ever sang the Star-Spangled Banner again while in BUD/S Training.

Published on May 05, 2014 04:25

Below is from Steve's upcoming interview with Henzel Przemysław of

Below is from Steve's upcoming interview with Henzel Przemysław of