Trace A. DeMeyer's Blog, page 5

September 13, 2025

Roadblocks

A few years ago, I received an email request to help the daughter of an adoptee. She was writing a dissertation on forced assimilation practices from the boarding school movement to the current foster care system for Indigenous communities in the U.S. "And, for that, I am also writing segments about my own life," she told me.

I told her that her story is about ROADBLOCKS.

I wrote to her:

I cannot stop thinking about your work. I am trying to research missing children, especially from Carlisle. Some died, but how? Some were placed with farm families off school grounds. Then disappear into thin air.What the governments did in establishing these residential schools was to create hostages - so their parents wouldn't make war.

Abusing a child is a criminal act but because it was a church school, they got a free pass? No charges?

Like slavery, they made examples and tortured and killed kids to scare the rest of the students... to make them literally insane and fear for their lives.

With adoption it was more permanent - families would be torn apart forever. Sealed files prevent reunion. Adoptees lose everything.

YOUR story is about your truth, how you are running into every roadblock to find your own tribal identity after his adoption. Most of the men adoptees tell me they never had a good relationship with a woman. They could never trust anyone.

This interior trauma follows an adoptee their entire life. Maybe it happened to your dad, too. Lots of medical terms exist: severe narcissistic trauma, PTSD, etc.

YOUR story is the roadblock. The printed one-sided oppressor history is bad which is also the goal of oppression.

If you tell your story of the roadblock, people will understand how the gov't wanted this to play out. Not only your dad but you are on the outside as well.

Tribal sovereignty - gone. Measuring blood - eventually there won't be any Indian left with enough blood. All the plan.

Family lore is not enough anymore... you have to be able to prove your direct connection to a tribe and have relatives who know you and accept you.

I opened my adoption despite all the roadblocks and was 38 when I finally met my birthfather. Am I enrolled? No. Why? I do not have a copy of my original birth certificate from Minnesota. I have met relatives on both sides.

Despite every roadblock, many many adoptees are finding their way home. I have two close friends who live on their rez and have met all their relatives. Long process but they did it.

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.me

Sibling drama ‘Meadowlarks’ examines ‘60s Scoop fallout

Family drama ‘Meadowlarks’ brings scattered ‘60s Scoop siblings together for one weekendCassandra Szklarski The Canadian Press Sep 7, 2025

TORONTO - Indigenous performers Michael Greyeyes and Michelle Thrush say the power of film is in bringing light to dark places, and that’s what they hope they can do with their ‘60s Scoop drama, “Meadowlarks.”

Directed by Tasha Hubbard, the family saga about four scattered siblings brought together for one weekend makes its world premiere Sunday at the Toronto International Film Festival, and screens again Monday.

It’s inspired by Hubbard’s 2017 documentary “Birth of a Family,” in which four Cree siblings who were taken from their mother as children gather for the first time as adults to piece together their family history.

Reached before TIFF in Naples, Fla., Greyeyes said the government policy remains little-known and “tragically” misunderstood today, more than a generation after 20,000 Indigenous Canadian children were put into foster care or placed for adoption with white families.

"There are various things that we talk about in our culture and people are familiar with them, like MMIW (missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls), things like intergenerational trauma — this kind of stuff, people have an understanding of it. And when I go, 'It's about the '60s Scoop,' even people who are pretty versed are like, 'Hmm, what's that?',” Greyeyes said in a joint video call with Thrush, who was in Calgary.

“This is not something that either Canada or the United States are proud of and they buried it. And part of our job as Indigenous artists is to make sure that the world knows our stories."

Thrush agreed, describing the job of an artist as "we bring light to places that were previously dark.”

“We often enter into territory that's not always talked about or safe or in general conversation," noted Thrush.

Thrush said much of the work involved conveying the inextricable bonds of siblings, but that it wasn't hard to forge a connection with her co-stars, also including Carmen Moore and Alex Rice.

“The characters, as siblings, they lost so many years together. And I felt like working with these three actors and Tasha as our leader, that was our mission, was to fill in that beauty and that love and that light for so many of our community members who are finding their way home,” said Thrush.

“And how incredibly courageous that is for so many people in our communities."

Reached in Edmonton, where she is an associate professor at the University of Alberta, Hubbard said Indigenous characters are too often treated as set dressing and their stories reduced to sad and tragic tropes. Indigenous creators are changing that, she said.

"We're not just victims all the time, our characters in our films are complicated and beautiful and messy and struggling and overcoming. We have this range of humanity that's been denied for a long time when it comes to film,” said Hubbard.

“I want to send a shoutout to (APTN/Crave series) ‘Little Bird’ and that beautiful series that told the story from childhood to reconnection and the struggles around that."

"I think this film is in conversation with that, (this time focused) around five people in their 50s, which is a special time of life."

“Meadowlarks” is set to open in theatres in November. The Toronto International Film Festival runs through Sept. 14.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 7, 2025.

VIAREVIEW: https://nextbestpicture.com/meadowlarks/

Press MaterialsTIFF Lightbox Film + EventsMeadowlarksMeadowlarks Tasha Hubbard WORLD PREMIERE Canada | 2025 | 91m | EnglishSpecial PresentationsFilm DescriptionBased on her 2017 documentary Birth of a Family, Tasha Hubbard’s Meadowlarks is an emotional drama that follows four siblings, separated by the Sixties Scoop, as they come together over a week.

Based on her 2017 documentary Birth of a Family, acclaimed filmmaker Tasha Hubbard has turned to drama for the first time. With Meadowlarks, she takes the story of four siblings, separated as babies, who are reuniting 50 years later during a week spent in Banff.

Kicking off with awkward small talk, gifts, and forced bonding events, the one brother and three sisters do their best to get to know one another after decades apart.

Their forced separation at birth was part of the Sixties Scoop, the term given for the then-common practice of removing Indigenous children from their families, often without consent, and placing them with the child welfare system. While documentaries have covered this topic over the years, nothing has ever fictionalized the experience of uniting as adults and coping with the consequences.

To tell her story, Hubbard has assembled a terrific roster of Indigenous acting stars to play the siblings, including Michael Greyeyes (40 Acres, TIFF ’24), Michelle Thrush (Bones of Crows, TIFF ’22), Carmen Moore (Unnatural & Accidental, TIFF ’06), and Alex Rice (On the Corner, TIFF ’03). Their surname translates to Meadowlarks.

An emotional journey handled with care, respect, and beauty — one of the Birth of a Family siblings is credited on Meadowlarks as executive producer while Hubbard is a Sixties Scoop survivor — Meadowlarks will leave you in tears, hugging your family members closer.

Content advisory: mature themes

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meRemains of Native American children to be returned to Oklahoma

This week, the U.S. Army announced that 19 Native American children will be disinterred from the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, where they were buried after being taken from their families more than a century ago.After more than a century, Native American children buried at a Pennsylvania boarding school will be returned to their families, marking a significant step toward healingVIDEO: https://www.koco.com/article/remains-of-native-american-children-returned-oklahoma/65985824

"These children have been waiting anywhere from 145 years to 126 years to come home,” said Norene Starr, special projects coordinator for the Cheyenne Arapaho Tribes

The effort to bring the children home has been ongoing for years, as tribes have been asking for their relatives back from the boarding school where more than 200 children died and are now buried.

"They have been gone, they’ve been missing, all this time, their families had no idea where they went or what happened to them. Some of them were never notified,” Starr said.

The 19 children are from the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe expressed hope that the journey to peace can begin, despite the long wait.

"It's going to bring a lot of peace, maybe not so much closure. It's something we have to do, and we have to do it for our people, and these children, we need to bring them home, so they can rest where they came from,” Starr said.

The tribes view the homecoming as a step toward healing after more than a century of loss.

"There is peace, and healing, and we have to be aware, we have to know and acknowledge everything that has happened before us," Starr said.

(Use the search bar to find all the coverage on Carlisle and the repatriation of these children...Trace)

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meThe Hug

READ: https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/briefings/measuring-mistrust-polls-politics-and-power

IN PICTURES

Jonathan Hooker shares a hug with his biological mother, Patsy George. Hooker is among an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children taken from their families during the ’60s Scoop. (Ruth Bonneville / Free Press)

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meMMIWG: Patricia Calahasen

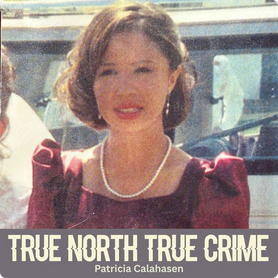

True North True Crime podcastEp. 130/ September 4, 2025

True North True Crime podcastEp. 130/ September 4, 2025It was the early hours of August 3rd, 2001, in Edmonton, Alberta, when fire crews responded to a dumpster blaze behind a central apartment building. Once the flames were out, they made a horrifying discovery — the burned remains of a young woman.

For nearly two weeks, investigators worked to find out who she was. They canvassed hundreds of apartments and narrowed their search to a short list of missing women. Dental records would confirm the victim was 18-year-old Patricia Calahasen.

What police uncovered next was a story of trust betrayed, a violent assault, and a desperate attempt to destroy the evidence. The person responsible was just 17 years old. But for Patricia’s family, the fight for justice has lasted decades.

--

This podcast is recorded on the territories of the Coast Salish people.

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meMemoir gives voice to #60sScoop experience of being raised outside of Indigenous culture

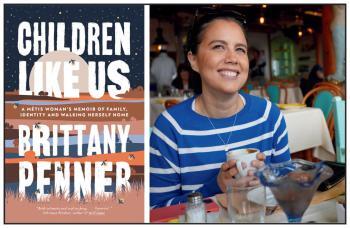

Brittany Penner. Photo supplied. Credit Michael Maren. By Shari Narine, Windspeaker.com Books Feature Writer

Brittany Penner. Photo supplied. Credit Michael Maren. By Shari Narine, Windspeaker.com Books Feature WriterSeptember 4th, 2025

Children Like Us: A Métis Woman's Memoir of Family, Identity and Walking Herself Home is Brittany Penner’s account of being adopted as a baby by a Mennonite family in Manitoba and searching for her birth parents.

Such an adoption practise—having white families raise Indigenous children—continues, points out Penner, who is now 36 years old.

“I really keep thinking about…how many children and teenagers are still facing realities like this where…they have been cut off from their first families, where they're being raised outside of their culture, and how it's not something that's in the past. It is something that is still very present across our country today,” said Penner, who has Anishinaabe, Cree and European settler lineage.

When Penner started writing her memoir, it was under a different title. But when she explained it to people, the phrase “children like us” kept coming up.

“It was always in reference to…children who were Indigenous, who were placed for adoption or relinquished or apprehended or in foster care. And that was just how I think, and my siblings and my cousins, collectively, thought of ourselves,” she said.

Penner and the other Indigenous children who were fostered or adopted by her extended Mennonite family were part of the Sixties Scoop, a common practise by the Canadian government to place Métis, First Nations and Inuit children with non-Indigenous families in other provinces and sometimes in other countries. The Sixties Scoop began in the 1950s, ramped up in the 1960s, and carried through until mid-1980. It’s estimated 20,000 children were taken.

Penner was the only child her parents adopted. She had numerous foster siblings (21 before her seventh birthday), who she connected with as brothers and sisters only to have them torn away from her over the years. Due to these losses, as a youngster she became obsessed with when she would be taken away, and it was a fear she lived with despite her mother’s attempted reassurances that that that would not happen to her. Her father’s Mennonite family, including his parents, adopted and fostered numerous Indigenous children. These were the Native aunts and uncles and cousins that Penner grew up with.

In offering her story, Penner cautions the reader in the book’s foreword that this is “not a memoir wherein I ask you to choose a side.” She says that mattered to her because, when she was growing up, she was told she “should be grateful” that her adoptive parents had chosen her.

As she writes in her memoir, “I’m adopted. I’m reminded of this again and again and again—until I begin to believe there is something inherently wrong with me for not feeling unendingly lucky.”

keep reading👇

“The side that was praised as a child was the nurture…and that was very, very emphasized,” said Penner. “As a reaction to having so much taken from me at birth in terms of where I came from and my identity and who my family was, I put a lot of emphasis on the nature in terms of where I came from. I think I've come to land at a place where I have really come to see the value in both. I think that it's human nature to sometimes want to place more value on one side or another depending on where we're at in terms of reckoning with our own stories.”Penner recounts her painful journey of discovering Crystal, her birth mother. But once contact was made, it wasn’t smooth building a relationship. She also reached out to her birth father.

Penner notes in her book that she doesn’t expect her adoptive father to read her memoir and doesn’t know if either her adoptive mother or birth mother will read it.

For her adoptive parents, she said, “There might be some fear around what the book might contain and fear of the unknown and maybe fear of knowing…my personal and internal experiences.”

As for Crystal, Penner said, “I can see her picking it up. I can certainly see her supporting me and finding a copy. I don't know if she'll read it or not.”

Children Like Us is not the first time Penner has shared her story publicly. Since 2021 she has written personal essays that have been published. The response she received included “racist rhetoric…similar to some of the things I’ve been hearing my whole life. And the fact that I had heard them before as a child or a teenager didn't necessarily make it any easier when I heard it with those pieces.”

But telling her story in Children Like Us is “hugely important,” said Penner. “I don't think I would have put myself out there in what feels like such a vulnerable and emotionally honest way if I didn't really believe in the importance of it.”

Penner says when she was growing up, and even now, the only narratives she sees about fostering and adopting are written from the points of view of the parents.

Penner, now a physician, blends modern medicine and holistic approaches along with personal therapeutic work in her practice. A number of her patients have similar stories to hers.

“When I was writing this book, (I was) just thinking, ‘I'm writing this for you. I have hope for you. I'm holding hope for you.’ So I hope that patients can see this and think, ‘Wow, my potential to hope for a life that is filled with whatever I want it to be filled with is actually so much higher than I might have been told and there is still a chance for me to find my culture again’,” said Penner.

As for foster or adopted families, many of whom are also part of Penner’s practice, she said she wants parents to look at their children “in a slightly new light. (That) seems like a really beautiful idea to me. Or parents having newfound compassion for their children because of what they've read seems very beautiful to me.”

Children Like Us: A Métis Woman's Memoir of Family, Identity and Walking Herself Home is published by Doubleday Canada and will be available Sept. 5. It can be ordered online at amazon.ca.

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meAugust 23, 2025

Hiatus

Yup, every one needs to go outside and relax.

We'll be back posting next month!

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.me‘Sisters in the Wind’

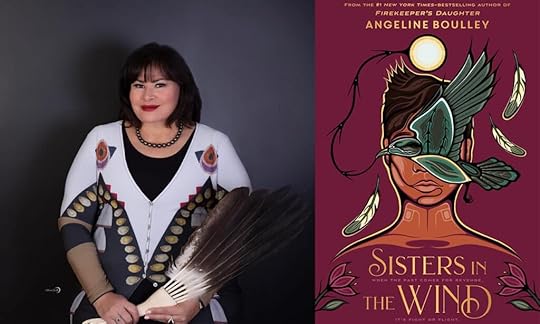

Angeline Boulley’s third novel, “Sisters in the Wind” chronicles an Ojibwe teen girl’s experience in foster care. Provided photos.

Angeline Boulley’s third novel, “Sisters in the Wind” chronicles an Ojibwe teen girl’s experience in foster care. Provided photos.“Native families are like onions,” fiction author Angeline Boulley writes in her latest novel about Indigenous families caught up in the child welfare system.

They are “rough-looking on the outside,” she goes on. “People want to peel the outer layers and toss them away, as if they have no value. But each layer is protecting the next, down to its innermost core. That green center, where the onion is sweetest, that’s the Native child. Surrounded by layers of family and community.”

Boulley’s third book, “Sisters in the Wind,” offers a rare Indigenous-centric glimpse into the failings of the country’s child welfare system. The young adult novel, set to publish next month, is meant to show what can happen when a federal law meant to ensure that Indigenous families remain intact is not followed, and how a child’s life can be improved when it is, the Michigan author said in a recent interview.

The thriller follows Lucy Smith, an Ojibwe teen who is running for her life, away from traumatic figures she encountered while growing up in foster care. As an adult she navigates a difficult childhood spent in various placements before finding family and healing.

Publisher’s Weekly called the book a devastating, gripping tale “that serves as a searing critique of the ways that systems can fail vulnerable youth.”

At points in the novel, Boulley’s protagonist experiences dehumanizing moments common to foster youth everywhere, including when she is forced to carry her belongings in a trash bag during a move to a new home.

Recently, states including New York and Texas have prohibited child welfare agencies from doling out trash bags, and now require them to provide proper suitcases to children. Such laws, “need to be everywhere,’’ Boulley said, adding that she believes making foster youth use garbage bags sends the clear message, “that they themselves are trash.’’

An insight into Angeline Boulley’s creative process: Color-coded spreadsheets detail characters’ lives and her cat, Pietro, comforts her. Provided photo.

An insight into Angeline Boulley’s creative process: Color-coded spreadsheets detail characters’ lives and her cat, Pietro, comforts her. Provided photo.As an adult, Smith eventually goes to work as a research intern for a company that trains child welfare professionals on the workings of the Indian Child Welfare Act. The 1978 federal law, known as ICWA, requires state foster care agencies to take extra steps to ensure Indigenous families stay together. The fictional company in the novel is based on real work Indigenous people are doing to preserve families and tribal communities in Boulley’s home state of Michigan, she said.

In the case of the novel’s protagonist, ICWA was not followed as she moved through the foster care system. In one bleak scene, a social worker tells Smith that identifying as Indigenous will only muddle her situation.

“It complicates everything,’’ Smith is told. “Just say you’re Mexican.”

Later, Smith comes to believe that the abusive situations she endured in non-Native foster homes never would have happened had she been placed with tribal relatives.

Boulley, a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa, hopes a particular message in her novel will reach child welfare professionals who might read it:

“When ICWA is followed correctly, it works,” Boulley said. “The issues that arise primarily come when social services and court personnel don’t understand the law. They continue with assumptions and misconceptions, and that ends up complicating children’s lives.’’

Boulley was never in foster care herself. But she and her siblings grew up spending summers visiting the Sault Ste. Marie reservation in Michigan where she knew several young relatives being raised by kin outside of the foster care system.

“Growing up, I didn’t think it was anything unusual to have cousins that were raised by my grandma,” Boulley said. “That was just normal.”

Her work on “Sisters in the Wind’’ began years ago, but she felt an urgency to complete it following recent legal challenges to ICWA. In a United States Supreme Court case two years ago, multiple states and three foster families argued that the federal statute was unconstitutional and interfered with a non-Indigenous couple’s right to adopt an Native child.

A Supreme Court ruling upheld the law in June 2023. But, Boulley said, “We know it’s not the final assault on tribal sovereignty.’’

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meAugust 20, 2025

UC Officials to Face Lawmakers Over Failure to Return Native American Remains and Artifacts

delay delay delay....

Top officials from the University of California were called to account Tuesday morning for their ongoing failure to return thousands of Native American human remains and hundreds of thousands of sacred cultural artifacts, as required by both federal and state law.

The hearing - scheduled for 9 a.m. in Room 1100 of the Capitol Annex Building at 1021 "O" Street - is a joint session of the Joint Legislative Audit Committee and the Assembly Select Committee on Native American Affairs.

Despite three critical audits over the past five years - in 2019, 2021, and most recently in April 2025 - UC has made limited progress in complying with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), enacted more than 30 years ago, and a similar California law passed 24 years ago.

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meDiné designer Amy Denet Deal brings indigenous fashion to Santa Fe

What brought you to Santa Fe? Were you born on nearby Diné land?

I was born in ‘64. The Indian Child Welfare Act was [enacted] after I was born, so I was adopted out. During Indian relocation in the 60s, my mom was relocated to Ohio, which was a very common way that the government spread out the Native youth to break up the uprisings.

She got pregnant with me out in the middle of nowhere in the Midwest, and I got snatched up by Catholic Charities and adopted out with no connection to my birth family and was raised by non-natives in the Midwest.

I had a great childhood, but no connection to culture — not for lack of love, just for lack of education and lack of protocol by the government. It’s a little bit different now: I'm very supportive of the Indian Child Welfare Act because it protects our children from what I've been through.

In hindsight, I learned amazing things in the outside world that I'm able to bring back. My reintegration— coming home — was in 2019. My daughter graduated high school, so in my empty nest phase, I was like, I'm going to learn what it means to become a Dinemic matriarch. I came home.

KEEP READING:

https://www.bizjournals.com/bizwomen/news/profiles-strategies/2025/08/amy-denet-deal.html

Questions? EMAIL: tracelara@pm.meTrace A. DeMeyer's Blog

- Trace A. DeMeyer's profile

- 2 followers