Arlene Miller's Blog, page 57

June 7, 2015

The 7 Deadly Sins of Writing: No. 6 – Inconsistency

When your writing is inconsistent, you look like you don’t have it “together.” When your writing is consistent, it appears that you know what you are doing — even if you don’t. Thus, it is better to have consistency in your writing.

When your writing is inconsistent, you look like you don’t have it “together.” When your writing is consistent, it appears that you know what you are doing — even if you don’t. Thus, it is better to have consistency in your writing.

Consistency is adhering to the same “rules” throughout a piece of writing. It includes the following elements: format, terminology, spelling, punctuation, verb tense, point of view, audience, and audience level.

Format: Obviously you want your margins to be the same throughout a memo, a letter, a white paper, a thesis, or an entire book. No matter what the length, the format should be consistent. Paragraph indents should all be the same. Tabs should be set the same. The same type of thing should be treated the same way throughout. If you use bullet lists, make the bullets the same. That doesn’t mean you can never use numbered lists in the same price of writing; sometimes numbered lists are needed. Spacing between sentences and paragraphs should be the same throughout. Headings should be consistently in the same font and size and style if they are the same type of heading. Notes or footnotes should receive similar treatment throughout. If you are using italics or “quotes” or bold for certain types of things in your writing, use them consistently. Don’t use quotes one time and the next time use bold for the same thing. Following one specific style guide, no matter which one it might be, will help. A consistent format is pleasing to the eye and makes whatever you write easier to read. It gives the reader confidence that you know what you are doing.

Terminology: If you are going to call a spade a spade, don’t call it something else the next time you refer to it! You get my point. Even something minor can throw the reader off and make the reader wonder if you are talking about the same thing or not. The First National Bank of Boston shouldn’t be referred to as The First Bank of Boston or the First National Bank of Boston the next time you use it. Don’t use someone’s first name alone and then their last name alone; the reader may not connect them and realize it’s the same person. Acronyms should be spelled out the first time you use them with their abbreviation included; then you can use just the abbreviated form. Inconsistent terminology can quickly confuse a reader.

Spelling: Here is a big one. Obviously you want to spell everything correctly. And you want to use either American or British spelling throughout, not a combination. However, some words, particularly hyphenated and compound words, can cause a problem. Is it email? e-mail? e mail? Well, look it up, and use the same reference book for the whole piece of writing. If there are conflicting spellings, or more than one, just pick one and use it throughout. It doesn’t matter what you choose; if you are consistent you give the impression that you know what you are doing and you care about your writing. With words like email that are fairly new to the language, here is what happens: these words generally start as two words. Then they are put together with a hyphen. When they become very common, they often become one word. Here is an exception to what I just said: You would say, “She is a three-year-old girl.” However, you would say, ” The girl is a three year old.” Such compound adjectives are hyphenated when they precede the noun they modify, but they are not if they come after the noun. So it might look inconsistent, but it isn’t.

Punctuation: I put this here for one reason only. Most punctuation goes by pretty standard rules. However, the Oxford comma is optional. That doesn’t mean you can use it some times and not use it other times in the same piece of writing. Pick one. Use it or don’t. Just be consistent.

Verb Tense: Use the same tense throughout your writing if you are talking about things happening at the same time. Of course, you can switch to past tense if something happened before the rest of your writing, but don’t needlessly switch from past to present.

Point of View: If you are writing in a first person point of view (I), don’t suddenly switch and begin saying you instead. And don’t begin by using you and then suddenly throw in a random one instead.

Audience: If you are writing to an audience that isn’t familiar with legal terms, don’t begin in layman’s language and then start throwing in legal terms. Keep the audience consistent.

Audience level: You might be writing to a group of physics professors. You might be writing to 8th graders. Keep that in mind. Don’t mix simple concepts and very complex ones, or throw in words you know your audience won’t understand. If you are writing to a lower-level audience, you might want to keep your sentences shorter and simpler too.

Writing with consistency will make your readers much happier. If you are using an editor, consistency is one of the things your editor will be looking for.

Trust is built with consistency.

Lincoln Chafee

June 6, 2015

The 7 Deadly Sins of Writing: No. 7 – Slang and Jargon

Jargon: Language that is often specific to a certain group or occupation and often not understood by “outsiders.”

Jargon: Language that is often specific to a certain group or occupation and often not understood by “outsiders.”

Slang: Current expressions, intentional misspellings, and other casual words and idioms

Neither slang nor jargon have much of a place in formal writing—especially slang. Judiciously used jargon may have a place.

Jargon: You have heard it.

Businesses use it:

We need to meet offline about this.

Our team has to ramp up our efforts.

Education uses it:

We need to use backwards planning.

I think we should common core this lesson! (Common Core is the new set of standards. A noun, it is also being used as a verb.)

You need to scaffold this lesson for some of the students.

Lawyers use it:

You have seen legalese. It tends to be wordy, unclear, convoluted, and to use certain antiquated words like herein.

Doctors use it:

Medical terminology is important and a language of its own. But the general pubic doesn’t understand much of it.

Buzzwords fit into the category of jargon. One of our teachers would lead us in Buzzword Bingo during our staff development days. He would create a buzzword board and hand it out. When we heard each buzzword, we would cross it off. I thought it was a joke until I saw one online today!

Of course acronyms are also jargon and are often overused and used without explanation. We discussed acronyms briefly in last week’s post.

Should we never use jargon? Jargon has its place. First, don’t overuse it. Second, know your audience. If you are writing to a general audience outside of your field, use it very sparingly and always define the terms you use. And always spell out acronyms and abbreviations the first time you use them, putting the acronym in parentheses. If you are writing to colleagues who understand the language, yes, you can use jargon. Well, let me clarify. Obviously, medical terms need to be used if you are writing to others in the field. That is a little bit different in terms of jargon. Something like “Let’s meet offline” should probably be avoided entirely in formal writing and reworded to less “jargonish” speech. How about “Let’s meet as a team later this week to discuss this issue before we announce anything.”

How about in education? Education has lots of buzzwords. Having listened to them, they get tiresome. Limit them!

Slang: Slang is informal. It is conversational at best. Don’t use it in formal writing:

That is a really cool idea. NO

What an awesome report that is! NO

I’m gonna get to that soon. NO

What’s up? NO

You want to use slang to make a point? Put it in quotes.

Obviously, if you are quoting someone, use the exact words whether the person uses jargon or slang. In quotes, anything is possible!

Enough said about that. We have come to the end of the 7 Deadly Sins of Writing, but I am sure we could think of more! If you have any more, please comment “online or offline”!

May 30, 2015

Plans, Platform, and Promotion

I am veering away from my usual type of posts this week to write something a bit more autobiographical — and a bit more promotional.

I am veering away from my usual type of posts this week to write something a bit more autobiographical — and a bit more promotional.

The last two posts in the 7 Deadly Sins of Grammar series will be coming the next two weeks. And thank you to those who have asked me what my post on plagiarism had to do with grammar. Good question. I think the series would have been more aptly titled the 7 Deadly Sins of Writing, and that is indeed what I may have had in mind in the first place. But on to this post . . .

Plans – As you may know, I am retiring this week (from teaching) after eleven years of teaching English at a junior high school. The past four years of those eleven I have been working part time–every other day–so that I could devote time to writing and marketing my books. I have managed, in the past five years, to publish three print grammar books, two of which are currently also e-books; two short grammar books only in e-book format; and a novel. I have many other books in the queue that I would like to write. Hopefully, I will now have more time. And if you are a writer, you know that writing is the easy part: promoting is forever! Perhaps I will have more time for that too. I will continue to copyedit both fiction and nonfiction, and teach workshops and give grammar/writing/language talks wherever I am invited. I may also return to teaching as a substitute next winter. And of course, the blog will continue with more grammar, language, and writing posts—along with guest posts.

Platform – If you have written and published a book (or been a contestant in the Miss America pageant), you know that you need a platform, whether you write fiction or nonfiction. A platform comprises your intent (what are you trying to say in your book) and your audience. For example, my platform is helping people communicate more effectively and feel more confident about their writing through avoiding common grammar , punctuation, and word usage errors. Let’s say I wrote a novel with child abuse, or women’s rights, or bullying in the plot. There is my platform.

It is also crucial to know your audience. Some audiences are easy. Gardening books are written for those who enjoy gardening. A book on beginning gardening might have an audience of people who think they would like to try gardening, but don’t know much about it. With a grammar book it is easy to say, “My audience is everyone. Everyone needs good grammar, right?” Well, first of all, not everyone is interested in grammar or buying a book on the topic. Often, My audience is everyone turns out to be My audience is no one. It is very difficult to market to everyone. An author might have one obvious niche, many niches, or may choose a niche (or more than one) to market to.

Promotion – Well, that was a nice lead-in to the audiences for my grammar workbook. I have had trouble focusing in on which markets to target with my grammar books because there are so many. I was thinking about the hoards of people who might rush to buy a grammar workbook at the beginning of the summer: I am going on the assumption that people like workbooks; they like taking tests and finding out how they did. Here are some of my audiences:

Students from 10 through 18: My workbook is intended for anyone older than about 10. So a student in grades 6 through 12, let’s say, could go through the workbook during the summer and enter the next grade much more prepared to write (and do grammar in whatever capacity it is taught). So, motivated junior high and high school students are a good audience.

College Students: Many college students are taking remedial writing courses when they reach college; and both colleges and businesses complain about the lack of writing ability of their students and employees. Quite a few professors have used my book for their college classes of various types, including creative writing. So, college students, whether for a class or just to brush up on their grammar (punctuation, and word usage too) are another good audience for me.

Teachers: My students have come to me with varying degrees of grammar knowledge. Although it seems, in many cases, that grammar is not being taught very much these days, the new Common Core standards are full of grammar—and quite sophisticated concepts at early grades. I think part of the reason many teachers, particularly elementary school teachers, may not teach grammar much is because they are not too sure of some of the concepts themselves. If you don’t continue to use grammar, you may still use correct grammar, but you don’t remember why. I think teachers are an excellent audience for me.

Homeschool teachers/parents: Many homeschool teachers are the parents. Once again, unless you continue to use grammar in the capacity of teaching it, or as an editor, you tend to forget the rules. The workbook is a great review for homeshool instructors.

Job Hunters: If you need to write a cover letter, redo a resume, or begin interviewing, you need good writing and good speaking skills. A grammar review would be very helpful. And once you get the job, the book will continue to be helpful as a reference. Many people write a great deal in their jobs. I once did a workshop for accountants—number people—who told me that 90 percent of their job involved writing.

Test takers: There are many types of test takers. Many people take some type of college entrance or graduate school exam including SAT, GRE, MSAT, LSAT, GMAT. They generality involve writing, and some of them may contain grammar, usage, and punctuation questions as well. But in addition to those tests, there are many occupations where you must pass a grammar test to get hired. I have heard of grammar tests for such unlikely jobs as police officer.

Paralegals: I have had paralegals in my grammar classes. That is just one occupation where the comma has to be in the right place. And apparently attorneys are pretty fussy about this.

Those who are not native English speakers: It goes without saying that nonnative speakers can use an English grammar book. And may I add that nonnative speakers generally have the best grammar and know the most about English grammar.

College professors: All types of college classes require writing, so a grammar book is helpful; it doesn’t have to be a grammar class, or even a writing class.

Schools (private, public): Public schools have restrictions on what they buy for students. Private schools have more leeway and also tend to teach more grammar. The private school market is likely a good one for my grammar workbook.

So am I asking all of you who fit into any of the above categories to buy my workbook? Just a suggestion! It helps me to actually write down my audiences and give reasons, because I do have one of those topics where I can say the audience is everyone. But of course it isn’t. (But it’s almost everyone, isn’t it?)

By the way, The Best Grammar Workbook Ever is available in print only right now. I am preparing to create an e-book, but I am wondering if perhaps just a PDF would do, since it keeps its pagination, unlike an e-book. So while I ponder this issue (and welcome comments from you), I will wish you a happy week!

For the next two weeks, I will be back with the last two installments of The 7 Deadly Sins of Grammar (much more appropriately called Writing) with Jargon and Slang, and Inconsistencies.

Remember: A grammar workbook equals summer fun!

May 23, 2015

The 7 Deadly Sins of Writing: No. 5 – Plagiarism

Plagiarism is more than a deadly sin: it is a crime. If you get caught plagiarizing in junior high, for example, the least you can expect is a zero on the project or paper and probably a meeting with your parents. Get caught in college, you will likely get expelled — and what college or company will want you after that? Many schools now require that papers be put through a plagiarism checker before they are even accepted. I have never used one, but I have caught a few students plagiarizing by entering a string of their words into a search engine — the “old fashioned” way of catching a plagiarist. I am pretty sure, however, that I missed quite a few. You can really tell when a student is writing about a certain book that he or she has read, and the writing is way above that student’s ability and likely comes from Amazon or the book jacket — or perhaps, in some cases, was simply written by a parent.

Plagiarism is more than a deadly sin: it is a crime. If you get caught plagiarizing in junior high, for example, the least you can expect is a zero on the project or paper and probably a meeting with your parents. Get caught in college, you will likely get expelled — and what college or company will want you after that? Many schools now require that papers be put through a plagiarism checker before they are even accepted. I have never used one, but I have caught a few students plagiarizing by entering a string of their words into a search engine — the “old fashioned” way of catching a plagiarist. I am pretty sure, however, that I missed quite a few. You can really tell when a student is writing about a certain book that he or she has read, and the writing is way above that student’s ability and likely comes from Amazon or the book jacket — or perhaps, in some cases, was simply written by a parent.

Technology has made plagiarism very easy. No longer must we diligently copy someone else’s words. Now we can simply cut and paste them . . . sometimes a student doesn’t even change the font, even when it doesn’t match the rest of the paper (how careless and lazy!) And yes, I have had students deny that they copied even when I show them a printout from the Internet that matches their paper exactly!

What is plagiarism ?

Plagiarism is taking someone else’s words or ideas and passing them off as your own without giving credit to the source. There are a number of different levels of plagiarism:

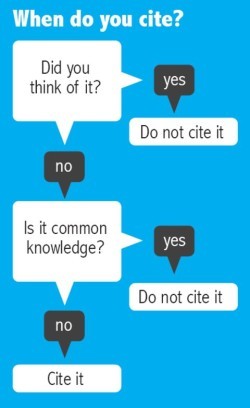

1. Copy and paste. Of course this is plagiarism. There is no attempt here to even change the wording. You can certainly copy someone’s words if you give credit to them and quote them. There are a number of ways to give credit:

Incorporate it into the writing: According to Dr. Peter Jones, in his 1980 study . . .

Use an in-text citation in parentheses next to the passage.

Use footnotes

Use notes at the end of the writing

And have a Works Cited list or Bibliography

2. Changing some words around. Still plagiarism. You cannot write basically the same thing as someone else and change every third word; this is still plagiarism, and the source needs to be cited. So you might not even bother to change the words. Just quote the original and give them credit.

3. Following the main gist of the passage, but changing the sentences. This is a bit more involved that #2. This type of plagiarism is keeping pretty much the same structure as something that is already written, but changing the sentences. It still says the same thing, and it still is not your original idea. Credit must be given. This type of plagiarism is probably the most common because people don’t think it is plagiarism. I am sure I am guilty of it myself (ouch!).

4. Paraphrasing is rewriting someone’s thoughts and ideas into your own words. Nice to do, but if it isn’t your idea, it’s plagiarism, so cite it. For example, you might read an article. You might then put it into your own words, perhaps a third of the length and completely different in paragraph and sentence structure — but not in idea. Cite it.

5. Just plain using someone’s ideas without developing your own and not giving credit to them. If it is someone else’s idea and you steal it without giving credit, you are plagiarizing.

What about common knowledge? Using common knowledge is NOT plagiarizing. For example, I do not give credit in my grammar books because grammar is common knowledge. No one person has the idea of what the subject of a sentence is. Historical facts, such as dates, are common also knowledge. Math formulae are common knowledge. However, if someone has a new idea about a historical event, or a new and novel math formula, that is an original idea and not common knowledge.

I would hate to not give credit in this article to where my information came from. Here are the links to some good information about plagiarism. And . . . be careful! Use safe text.

University of North Caroline Writing Center

Purdue University Online Writing Lab (OWL)

The 7 Deadly Sins of Grammar: No. 5 – Plagiarism

Plagiarism is more than a deadly sin: it is a crime. If you get caught plagiarizing in junior high, for example, the least you can expect is a zero on the project or paper and probably a meeting with your parents. Get caught in college, you will likely get expelled — and what college or company will want you after that? Many schools now require that papers be put through a plagiarism checker before they are even accepted. I have never used one, but I have caught a few students plagiarizing by entering a string of their words into a search engine — the “old fashioned” way of catching a plagiarist. I am pretty sure, however, that I missed quite a few. You can really tell when a student is writing about a certain book that he or she has read, and the writing is way above that student’s ability and likely comes from Amazon or the book jacket — or perhaps, in some cases, was simply written by a parent.

Plagiarism is more than a deadly sin: it is a crime. If you get caught plagiarizing in junior high, for example, the least you can expect is a zero on the project or paper and probably a meeting with your parents. Get caught in college, you will likely get expelled — and what college or company will want you after that? Many schools now require that papers be put through a plagiarism checker before they are even accepted. I have never used one, but I have caught a few students plagiarizing by entering a string of their words into a search engine — the “old fashioned” way of catching a plagiarist. I am pretty sure, however, that I missed quite a few. You can really tell when a student is writing about a certain book that he or she has read, and the writing is way above that student’s ability and likely comes from Amazon or the book jacket — or perhaps, in some cases, was simply written by a parent.

Technology has made plagiarism very easy. No longer must we diligently copy someone else’s words. Now we can simply cut and paste them . . . sometimes a student doesn’t even change the font, even when it doesn’t match the rest of the paper (how careless and lazy!) And yes, I have had students deny that they copied even when I show them a printout from the Internet that matches their paper exactly!

What is plagiarism ?

Plagiarism is taking someone else’s words or ideas and passing them off as your own without giving credit to the source. There are a number of different levels of plagiarism:

1. Copy and paste. Of course this is plagiarism. There is no attempt here to even change the wording. You can certainly copy someone’s words if you give credit to them and quote them. There are a number of ways to give credit:

Incorporate it into the writing: According to Dr. Peter Jones, in his 1980 study . . .

Use an in-text citation in parentheses next to the passage.

Use footnotes

Use notes at the end of the writing

And have a Works Cited list or Bibliography

2. Changing some words around. Still plagiarism. You cannot write basically the same thing as someone else and change every third word; this is still plagiarism, and the source needs to be cited. So you might not even bother to change the words. Just quote the original and give them credit.

3. Following the main gist of the passage, but changing the sentences. This is a bit more involved that #2. This type of plagiarism is keeping pretty much the same structure as something that is already written, but changing the sentences. It still says the same thing, and it still is not your original idea. Credit must be given. This type of plagiarism is probably the most common because people don’t think it is plagiarism. I am sure I am guilty of it myself (ouch!).

4. Paraphrasing is rewriting someone’s thoughts and ideas into your own words. Nice to do, but if it isn’t your idea, it’s plagiarism, so cite it. For example, you might read an article. You might then put it into your own words, perhaps a third of the length and completely different in paragraph and sentence structure — but not in idea. Cite it.

5. Just plain using someone’s ideas without developing your own and not giving credit to them. If it is someone else’s idea and you steal it without giving credit, you are plagiarizing.

What about common knowledge? Using common knowledge is NOT plagiarizing. For example, I do not give credit in my grammar books because grammar is common knowledge. No one person has the idea of what the subject of a sentence is. Historical facts, such as dates, are common also knowledge. Math formulae are common knowledge. However, if someone has a new idea about a historical event, or a new and novel math formula, that is an original idea and not common knowledge.

I would hate to not give credit in this article to where my information came from. Here are the links to some good information about plagiarism. And . . . be careful! Use safe text.

University of North Caroline Writing Center

Purdue University Online Writing Lab (OWL)

May 17, 2015

A Short History of the English Language

At Copperfield’s Books in Petaluma

I was so busy getting ready for my book launch a couple of days ago that I forgot I had a blog post to write! I have been writing this blog for over two years, a post sometime every weekend, and I haven’t missed a post yet. So, if you added yourself to the mailing list at the book launch, you will be reading some of what you heard, and I apologize. However, if you look back at previous posts, I know you will find some interesting things!

Back to the launch: Usually when I speak before a group, I use a grammar quiz, so it is interactive. This is probably the first time I have given a true 30-40 minute speech, so it did take some time to prepare. I had 13 pages of notes! Of course, they were printed in 16-point type, so I wouldn’t need my reading glasses.

I talked about the state of the English language and then gave some history of how it came to the point it is at now. Then I presented some things that have been in previous blog posts: funny phobias, readers’ pet peeves, and interesting things about the language.

Thank you to everyone who came to the launch, by the way! It was standing room only, with many seats taken by enthusiastic 7th graders! Yes, there were adults there, and even a dog! We had some laughs, we sold some books, we ate some cake . . . it was a good evening.

So where did this crazy language of ours come from, anyway?

English is a hodgepodge of, among other things, Latin, Greek, French, German, and Dutch.

Chaucer was the first person to choose to write in English, but Shakespeare was the most famous. He added many words to the language. Words first seen in Shakespeare’s plays include accommodation, assassination, dexterously, dislocate, indistinguishable, obscene, premeditated, reliance, and submerged.

Many of our common idioms were either coined by Shakespeare himself or were first seen in his plays: it’s Greek to me, salad days, vanished into thin air, refuse to budge an inch, green-eyed jealousy, tongue-tied, fast and loose, tower of strength, in a pickle, knit your brows, slept not a wink, laughed yourself into stitches, had too much of a good thing, have seen better days, lived in a fool’s paradise, the long and short of if, foul play, teeth set on edge, in one fell swoop, without rhyme or reason, give the devil his due, dead as a door nail, eyesore, laughing-stock, and devil incarnate.

Did you know that Shakespeare had one of the largest vocabularies of any English writer — 30,000 words? Estimates of an educated person’s vocabulary today is a mere 15,000 words.

The King James Bible, published in the year Shakespeare began working on his last play, The Tempest, contains only 8,000 different words.

The first English dictionary was published in 1604 with 120 pages, the same page count as my first book, The Best Little Grammar Book Ever! Perhaps it should have been called The Best Little English Dictionary Ever! — but it was called A Table Alphabeticall, written by Robert Cawdray. It contained “hard words for ladies or other unskillful persons.”

In 1806 Webster published his first dictionary, having written some grammar and spelling books prior to writing the dictionary.

And here is how our language became so colorful:

Let’s talk about the Irish for a minute: The word brogue sounds like the Irish word for shoe: the Irishman was said to speak with a shoe on his tongue! Some details of American grammar, syntax, and pronunciation are from the Irish, such as I seen instead of I saw and youse for the plural you.

Black English, for many, represents the disadvantaged past, slavery, something best forgotten, yet we gained some rich language: voodoo, banjo, banana, high-five, jam sessions and nitty-gritty.

Jive talk from the musicians and entertainers in Harlem added to this list: chick, groovy, have a ball, this joint is jumping, square, and yeah, man.

The first pioneers to arrive in this country needed to make up some new words. Some of these first Americanisms are lengthy, calculate, seaboard, bookstore, and presidential, with pretzel, canyon, and wigwam from the native Americans.

New Orleans gave us words like brioche, jambalaya, and praline. (Yum!)

Gold rush words include bonanza (originally meaning fair weather in Spanish), pan out, stake a claim, and strike it rich.

Yiddish words come from the Jewish-Americans, many of whom were in the media, many of them comedians: chutzpah, schlep, shtick, mensch, nebbish, schlemiel, schmooze, meshugunner, and yenta.

I think I will stop here. There are obviously newer additions to the language: surfer talk, Valley Girl words, and now tech words — and emojis, which aren’t words at all!

I would like to thank everyone who supported me by coming to the book launch; Copperfield’s Books for once again hosting me in fine style; and The Story of English by McCrum, MacNeil, and Cran for providing me with much of this information!

Next week: Yes, back to the Seven Deadly Sins of English series!

May 8, 2015

A Mother’s Day Post from The Grammar Diva

We interrupt our series of the 7 Deadly Sins of Writing to present our Mother’s Day post . . . .

We interrupt our series of the 7 Deadly Sins of Writing to present our Mother’s Day post . . . .

This post is dedicated to

~ My mother ~ (angel) Beatrice (Gold) Kelfer

~My grandmother ~ (angel) Etta Gold

and the three young adults who make me proud to be a mother!

~ My son ~ Jake Richard Miller

~ My daughter ~ Shelley Gold (Miller) Bindon

~ My son-in-law Joshua Kristian Bindon

Mother: A female parent

The origin of mother is pre-900 from Middle English moder, Old English mōdor; cognate with Dutch moeder, German Mutter, Old Norse mōthir, Latin māter, Greek mḗtēr, Sanskrit mātar. As in father, th was substituted for d, possibly on the model of brother (from Dictionary.com).

Some of the words that come from the Latin root mater (mother) are common today:

*matrimony – marriage

*matron – a married woman, particularly one with a mature appearance

*matricide – the killing of one’s mother

*matrix – the womb, that from which something originates

*matriarch – female head of family

*matriarchy – organization in which the mother is recognized as the head

*maternal – motherly

*maternity – the state of being a mother

*matrifocal – sociological group having a female leader

*matrilineal – derived from the female line of the family

We know that those words are related to the Latin root word that means mother. But we also use many other “mother” words. Here are some:

*alma mater is the school you graduate from — the mother school.

*mother-in-law

*wicked (or not) stepmother

*motherboard (of a computer)

*motherhood

*Mother Goose

*motherland

*motherlode

*mother of pearl

*mother tongue

*Mother Superior

*Mother Nature

*Mother of God (usually an interjection)

*Fairy Godmother

*mother hen

*housemother

*den mother

*Mothers of Invention

*Earth mother

and of course . . .

*Mother F….

otherwise, simply known as “Mother,” or, alternatively, “Mutha”

*****************************************************************************************************

So, what is a mother? When our human babies leave the nest, many of us adopt fur babies, the dogs and cats that become our new children. (Possibly feather babies, as well.) So we know that not only do we not need to be biologically related to be a mother, but we don’t even need to be of the same species.

We can even be mothers to things that are not living. Many of us have “birthed” books, for example. There are actually people who help other people birth their books, sometimes called book midwives. After you have slaved over a hot computer for months — sometimes years — and have produced a book, you certainly feel as if you have given birth to something.

How clever of me to go from mothers to books! That reminds me to tell you again that I will be launching my new book – The Best Grammar Workbook Ever – on Friday, May 15 (mark your calendars) at 7 p.m. at the Petaluma Copperfield’s Books for those of you who are local. If you reserve a seat, your book (should you choose to purchase one) is 20% off. But don’t feel you have to buy anything! There will be chocolate cake and a giveaway. And I will be talking about something that is related to words and language!

A book launch: A celebration of birth. So is it to be likened to a Christening? Baptism? No, wait… I am Jewish. A bris? Oh, I don’t think so. And the book isn’t old enough for a Bar Mitzvah. Or is the book female, and is it a Bat Mitzvah? I will have to think about this . . .

To close, here are a few quotes about mothers you might enjoy:

Mother’s love is peace. It need not be acquired, it need not be deserved. -Erich Fromm

Children are the anchors that hold a mother to life. -Sophocles

Yes, Mother. I can see you are flawed. You have not hidden it. That is your greatest gift to me. -Alice Walker

A father may turn his back on his child, brothers and sisters may become inveterate enemies, husbands may desert their wives, wives their husbands. But a mother’s love endures through all. -Washington Irving

My mother told me to be a lady. And for her, that meant be your own person, be independent. -Ruth Bader Ginsburg

No woman can call herself free who does not own and control her body. No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother. -Margaret Sange

Happy Mother’s Day to all types of mothers!

May 2, 2015

The 7 Deadly Sins of Writing: No. 4 – Trusting Spell Check

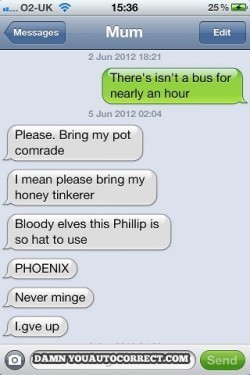

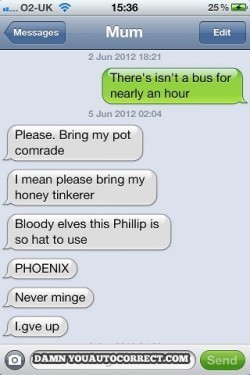

I was recently sending a message on Words with Friends. I was writing the simple word men. Auto correct wrote it as Mennonite. Last week I was attempting to text the word ouch. Auto correct changed it to polychrome. I have had auto correct change innocent words to slut and change lunch to lust. Lesson learned: Either turn the thing off or make sure you look at what you have written before you send it!

I was recently sending a message on Words with Friends. I was writing the simple word men. Auto correct wrote it as Mennonite. Last week I was attempting to text the word ouch. Auto correct changed it to polychrome. I have had auto correct change innocent words to slut and change lunch to lust. Lesson learned: Either turn the thing off or make sure you look at what you have written before you send it!

Siri (or whatever you might call that imaginary friend you have on your phone) is equally obtuse. If you ask her to send a text, don’t trust her. She apparently has poor hearing. Always check out a text she has written for you before you send it.

I must admit I don’t pay much attention to what I have set on my computer. There is auto correct, and then there is spell check (and grammar check). I guess auto correct can be helpful (?), but you must always proofread anyway!

Which brings us to spell check. Spell check is a wonderful invention. Whenever you write anything, you should run it through whatever spell checker you have available. Certainly, if you have a book manuscript, you should run it through spell check before you submit it to an editor. Whenever I receive a book manuscript to edit, and I can tell it hasn’t been run through spell check, I wonder why the author didn’t bother to do that. If the editor has to make the changes it costs time (and therefore, money). Yes, as an editor, I always do run it through spell check when I am finished with it in case I have missed anything.

If you are writing a book, running it through spell check is enough before you submit it to an editor. The editor should catch what spell check didn’t. However, if you are writing something that will not be edited by anyone else, DON’T RELY ON SPELL CHECK. You probably know this by now:

Spell check will not catch the fact that men has been changed to Mennonite by your autocorrect, since spell check doesn’t care what is being written as long as it is spelled erectly. (There you go . . . autocorrect. You wouldn’t want correctly to go out to the public as erectly now, would you? And while we are on the subject, you would’t want public to go out as pubic either . . . would you?)

Spell check will not find the pesky typos we all make: its versus it’s ; there versus their , your versus you’re . You (or your editor) need to go through the document to make sure none of that stuff exists.

Sometimes spell check is packaged along with a “grammar checker.” Other times, they are separate. There are also some grammar checkers online that you can run your writing through, some free, some for a fee. I am not too familiar with them because I don’t use them. I know that Grammarly has a pretty good one for a fee. I would love to put a grammar checker on my website, but my technical know-how (and likely my wallet) prohibit it at this time.

BUT. . . even if you use a grammar checker, you still need to proof your own work afterwards. Sometimes the grammar checker (like spell check) will stop at each “mistake” and you can decide whether to fix it. Many times they aren’t mistakes at all, but intentional. For example, a grammar checker may point out that you have written something in passive voice. It doesn’t like it. However, there is nothing illegal about passive voice, and you may have done it for a good reason. Same with fragments: grammar checkers don’t like them, and with good reason. However, sometimes people use sentence fragments in their writing for a reason.

I think grammar checkers are fine, especially for the more writing challenged. However, you cannot always listen to them. Why? Because THEY AREN’T HUMAN and they don’t have the same type of brain that humans do.

Lesson learned: Autocorrect is helpful (well, that is debatable). Spell checkers and even grammar checkers are helpful and great inventions for all of us writers. However, the human touch is also necessary, because our brains can discriminate. When you use writing tools, always make sure that you have the last word (and the last look).

The 7 Deadly Sins of Grammar: No. 4 – Trusting Spell Check

I was recently sending a message on Words with Friends. I was writing the simple word men. Auto correct wrote it as Mennonite. Last week I was attempting to text the word ouch. Auto correct changed it to polychrome. I have had auto correct change innocent words to slut and change lunch to lust. Lesson learned: Either turn the thing off or make sure you look at what you have written before you send it!

I was recently sending a message on Words with Friends. I was writing the simple word men. Auto correct wrote it as Mennonite. Last week I was attempting to text the word ouch. Auto correct changed it to polychrome. I have had auto correct change innocent words to slut and change lunch to lust. Lesson learned: Either turn the thing off or make sure you look at what you have written before you send it!

Siri (or whatever you might call that imaginary friend you have on your phone) is equally obtuse. If you ask her to send a text, don’t trust her. She apparently has poor hearing. Always check out a text she has written for you before you send it.

I must admit I don’t pay much attention to what I have set on my computer. There is auto correct, and then there is spell check (and grammar check). I guess auto correct can be helpful (?), but you must always proofread anyway!

Which brings us to spell check. Spell check is a wonderful invention. Whenever you write anything, you should run it through whatever spell checker you have available. Certainly, if you have a book manuscript, you should run it through spell check before you submit it to an editor. Whenever I receive a book manuscript to edit, and I can tell it hasn’t been run through spell check, I wonder why the author didn’t bother to do that. If the editor has to make the changes it costs time (and therefore, money). Yes, as an editor, I always do run it through spell check when I am finished with it in case I have missed anything.

If you are writing a book, running it through spell check is enough before you submit it to an editor. The editor should catch what spell check didn’t. However, if you are writing something that will not be edited by anyone else, DON’T RELY ON SPELL CHECK. You probably know this by now:

Spell check will not catch the fact that men has been changed to Mennonite by your autocorrect, since spell check doesn’t care what is being written as long as it is spelled erectly. (There you go . . . autocorrect. You wouldn’t want correctly to go out to the public as erectly now, would you? And while we are on the subject, you would’t want public to go out as pubic either . . . would you?)

Spell check will not find the pesky typos we all make: its versus it’s ; there versus their , your versus you’re . You (or your editor) need to go through the document to make sure none of that stuff exists.

Sometimes spell check is packaged along with a “grammar checker.” Other times, they are separate. There are also some grammar checkers online that you can run your writing through, some free, some for a fee. I am not too familiar with them because I don’t use them. I know that Grammarly has a pretty good one for a fee. I would love to put a grammar checker on my website, but my technical know-how (and likely my wallet) prohibit it at this time.

BUT. . . even if you use a grammar checker, you still need to proof your own work afterwards. Sometimes the grammar checker (like spell check) will stop at each “mistake” and you can decide whether to fix it. Many times they aren’t mistakes at all, but intentional. For example, a grammar checker may point out that you have written something in passive voice. It doesn’t like it. However, there is nothing illegal about passive voice, and you may have done it for a good reason. Same with fragments: grammar checkers don’t like them, and with good reason. However, sometimes people use sentence fragments in their writing for a reason.

I think grammar checkers are fine, especially for the more writing challenged. However, you cannot always listen to them. Why? Because THEY AREN’T HUMAN and they don’t have the same type of brain that humans do.

Lesson learned: Autocorrect is helpful (well, that is debatable). Spell checkers and even grammar checkers are helpful and great inventions for all of us writers. However, the human touch is also necessary, because our brains can discriminate. When you use writing tools, always make sure that you have the last word (and the last look).

April 23, 2015

The 7 Deadly Sins of Writing: No. 3 – Verbosity

Verbosity: Superfluity of words; wordiness

Verbosity: Superfluity of words; wordinessIn this blog post, we will show three forms or wordiness:

Filler words and phrases

Excess verbiage

Redundancy

1. Some people like to use words to fill space, hold the floor as they are thinking, or make those they are talking to feel smaller than a flea.

The overuse of uh, so, well , and you know can be used to fill space while the speaker thinks of what to say next.

Some people like to add phrases to the end of what they say to make you feel stupid: “Understand?” “Do you know what I mean ?” “Did you get that?” “Right?” and similar things.

2. Excess verbiage can be wordy phrases, larger-than-necessary words, and more words than necessary.

Wordy phrases can start sentences: “What is did is . . . “ or “What this means is . . .” or “The reason is because [yuck!!!]. . .” and even worse, using a double is : “What I did is is . . .” Then there is “The fact that . . .” and “That being said . . .”

Using fancy words doesn’t usually make you sound smart: conversate instead of converse or talk; using words like enormity and orientate. You don’t need to use a twenty-five cent word when you can use a nickel word.

“We will elect a president at the next meeting.” Or you could say, “The election of the president will be held at the next meeting.” The first one is far more direct and has more punch. Using a noun (election) instead of the verb is called nominalization.

If you have ever read your mortgage papers or any other contract, you have seen verbosity in the form of legalese.

3. Redundancy is usually done by mistake or because the writer or speaker doesn’t realize he or she is doing it. Here are some common redundancies:

7 p.m. in the evening (of course p.m. is in the evening!)

At this point in time is just a wordy way to say now.

Completely unanimous is the only type of unanimous there is.

The result is generally at the end, so end result is redundant.

In close proximity to is just a fancy way to say near.

For the purpose of is a puffed up way of saying to.

Each and every? Just each or every alone will do nicely.

Postpone until later? Can we postpone until any other time?

Past history really just means history, since there is no real future history.

Protest against ? Can you protest for something?

We made a decision is a nominalization for we decided.

Small in size? Small should do it.

Due to the fact that this blog post is about redundancy and other excess verbiage, I would like to repeat again, that my personal opinion is that now you know the basic essentials of this difficult dilemma. It should be noted that the final outcome of this blog post is hopefully spelled out in detail to you, my invited guests. Do you understand?

Save the Date!

Book Launch for The Best Grammar Workbook Ever! Friday, May 15 at 7 p.m.