Priscilla Paton's Blog, page 2

August 21, 2019

Back to School with the Craft of Writing: Lessons from Charles Baxter, Walter Mosley, Elizabeth George, Ben Percy, and Richard Russo

I can write. I can write a statement like “Where’s the coffee?” and realize that it is not a statement but a question fraught with suspense. Then I can write “We’ve run out” and realize that a crisis will ensue.

Conjuring up a fat novel out of thin air, however, is not a basic Reading-Riting-Rithmatic skill learned in third grade despite one’s inattention. After taking the baby steps of “my summer vacation was fun,” fashioning a novel is like climbing Mt. Everest. All right, I confess, the mountain metaphor comes from Charles Baxter. I attended a writer’s conference (it enhances sanity to occasionally leave the house), and Baxter said, not to me specifically (I was a butt-on-the-seat), that it didn’t get easier: writing each novel was like facing another mountain to climb. If an accomplished award-winning profound author like Baxter finds each book a struggle against gravity and fear, what are flatlanders like me to do?

Reading the wisdom of others is a reliable tactic. The number of books on writing is vast and not all are tailored to your needs. Here are a few I admire.

I would not have started a novel if I had not read on a plane Walter Mosley’s This Year You Write Your Novel. Mosley, creator of African-American investigator Easy Rawlins, provides the essential lesson—get started. I learned that I did not have to begin that middle-school terror, an outline. Roman Numerals, Capitals, lowercase letters, indents within indents to be graded—need I say more. If I had a concept, I could wing a draft. You may recognize this as the “seat-of-the-pants” approach. The term I prefer is “builder” with an ad-hoc blueprint. I concoct a rough synopsis, and after drafting out about seventy pages, I outline. I go back and forth from quasi-free writing to structuring. (In defense of organization, there are many examples, including prolific C.J. Box who writes his novels on top of a detailed outline.) Mosley offers more advice, but his book is less dissertation and more helpful shove.

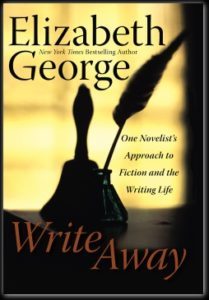

For something closer to a dissertation complete with subtitle, there’s Elizabeth George’s Write Away: One Novelist’s Approach to Fiction and the Writing Life. George is an American writer who outdoes the Brits on their home ground of literary mysteries with her Inspector Lynley mystery series. In Write Away, she provides a breakdown with illustrations from other writers (Toni Morrison to Stephen King) on character, plot, dialogue, scene, etc. George offers thorough advice on how to generate and how to control the tens of thousands of words that become a book.

Since I mentioned fear-master Stephen King, he has On Writing: A Memoir of The Craft. The “memoir” part intrigued me most. Like King, I’m from Maine and recognized the places and types he describes. While King grew up in down-and-out mill-town Maine, I grew up in farming Maine with Robert Frost scenery, and that has made all the difference.

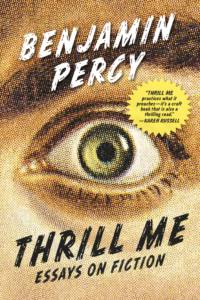

To continue down the dark path of horror, Ben Percy’s Thrill Me: Essays on Fiction discusses renditions of violence, suspense, and the supernatural. His workshop-style essays draw examples from canonized novels, comics, popular movies, and The Game of Thrones. Percy, whose characters in Red Moon are contemporary werewolves, takes on the tension between “serious” literature and “fun” genre to rise above it, or descend below, in exploring how to be “a writer and a storyteller.” Percy’s Thrill Me is published by the independent nonprofit press Graywolf (of course a wolf), which also publishes “the art of” series on writing, including Charles Baxter’s The Art of Subtext.

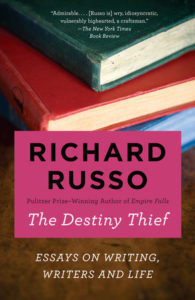

Other books probe writers’ sensibilities, the strange choices they make in art and life, and in Richard Russo’s words, the challenge of “getting good” and staying good. I’ll always read Russo, and his essays in The Destiny Thief are accomplished and self-deprecating enough (an old girlfriend says to him, “I never dreamed you had books in you) to carry off big proclamations: “The best humor has always resided in the chamber next to the one occupied by suffering”; “Hunger has no business preceding ability, but it always does, with no exceptions.” Russo’s version of Charles Baxter’s mountain is in this question: “could it be that the writer has to reinvent himself for the purpose of telling each new story?”

In honor of Toni Morrison, I’m about to read essays of hers in The Source of Self-Regard which interweave the role of writing with life-and-death social issues. If I want comfort, I return to Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings. While Welty is capable of savage wit in stories like “Why I Live at the P.O” and “Petrified Man,” her memoir is gently observant. Welty offers reassurance that you can be a writer even if you are not a Hemingway-esque brawler and bruiser. You can be a writer even if your parents love you.

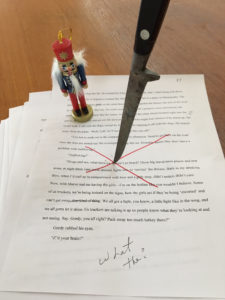

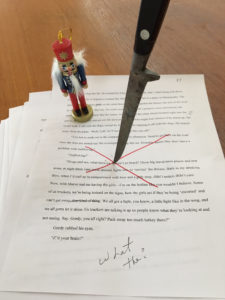

Murder Your Darlings

The post Back to School with the Craft of Writing: Lessons from Charles Baxter, Walter Mosley, Elizabeth George, Ben Percy, and Richard Russo appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

Back to School with the Craft of Writing: Lessons from Charles Baxter, Elizabeth George, Ben Percy, and Richard Russo

I can write. I can write a statement like “Where’s the coffee?” and realize that it is not a statement but a question fraught with suspense. Then I can write “We’ve run out” and realize that a crisis will ensue.

Conjuring up a fat novel out of thin air, however, is not a basic Reading-Riting-Rithmatic skill learned in third grade despite one’s inattention. After taking the baby steps of “my summer vacation was fun,” fashioning a novel is like climbing Mt. Everest. All right, I confess, the mountain metaphor comes from Charles Baxter. I attended a writer’s conference (it enhances sanity to occasionally leave the house), and Baxter said, not to me specifically (I was a butt-on-the-seat), that it didn’t get easier: writing each novel was like facing another mountain to climb. If an accomplished award-winning profound author like Baxter finds each book a struggle against gravity and fear, what are flatlanders like me to do?

Reading the wisdom of others is a reliable tactic. The number of books on writing is vast and not all are tailored to your needs. Here are a few I admire.

I would not have started a novel if I had not read on a plane Walter Mosley’s This Year You Write Your Novel. Mosley, creator of African-American investigator Easy Rawlins, provides the essential lesson—get started. I learned that I did not have to begin that middle-school terror, an outline. Roman Numerals, Capitals, lowercase letters, indents within indents to be graded—need I say more. If I had a concept, I could wing a draft. You may recognize this as the “seat-of-the-pants” approach. The term I prefer is “builder” with an ad-hoc blueprint. I concoct a rough synopsis, and after drafting out about seventy pages, I outline. I go back and forth from quasi-free writing to structuring. (In defense of organization, there are many examples, including prolific C.J. Box who writes his novels on top of a detailed outline.) Mosley offers more advice, but his book is less dissertation and more helpful shove.

For something closer to a dissertation complete with subtitle, there’s Elizabeth George’s Write Away: One Novelist’s Approach to Fiction and the Writing Life. George is an American writer who outdoes the Brits on their home ground of literary mysteries with her Inspector Lynley mystery series. In Write Away, she provides a breakdown with illustrations from other writers (Toni Morrison to Stephen King) on character, plot, dialogue, scene, etc. George offers thorough advice on how to generate and how to control the tens of thousands of words that become a book.

Since I mentioned fear-master Stephen King, he has On Writing: A Memoir of The Craft. The “memoir” part intrigued me most. Like King, I’m from Maine and recognized the places and types he describes. While King grew up in down-and-out mill-town Maine, I grew up in farming Maine with Robert Frost scenery, and that has made all the difference.

To continue down the dark path of horror, Ben Percy’s Thrill Me: Essays on Fiction discusses renditions of violence, suspense, and the supernatural. His workshop-style essays draw examples from canonized novels, comics, popular movies, and The Game of Thrones. Percy, whose characters in Red Moon are contemporary werewolves, takes on the tension between “serious” literature and “fun” genre to rise above it, or descend below, in exploring how to be “a writer and a storyteller.” Percy’s Thrill Me is published by the independent nonprofit press Graywolf (of course a wolf), which also publishes “the art of” series on writing, including Charles Baxter’s The Art of Subtext.

Other books probe writers’ sensibilities, the strange choices they make in art and life, and in Richard Russo’s words, the challenge of “getting good” and staying good. I’ll always read Russo, and his essays in The Destiny Thief are accomplished and self-deprecating enough (an old girlfriend says to him, “I never dreamed you had books in you) to carry off big proclamations: “The best humor has always resided in the chamber next to the one occupied by suffering”; “Hunger has no business preceding ability, but it always does, with no exceptions.” Russo’s version of Charles Baxter’s mountain is in this question: “could it be that the writer has to reinvent himself for the purpose of telling each new story?”

In honor of Toni Morrison, I’m about to read essays of hers in The Source of Self-Regard which interweave the role of writing with life-and-death social issues. If I want comfort, I return to Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings. While Welty is capable of savage wit in stories like “Why I Live at the P.O” and “Petrified Man,” her memoir is gently observant. Welty offers reassurance that you can be a writer even if you are not a Hemingway-esque brawler and bruiser. You can be a writer even if your parents love you.

Murder Your Darlings

The post Back to School with the Craft of Writing: Lessons from Charles Baxter, Elizabeth George, Ben Percy, and Richard Russo appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

March 25, 2019

Fairy Tales, Lake Superior, Minnesota Writer Leif Enger, and a Fish

I happen to read VIRGIL WANDER, by Minnesota writer Leif Enger, at the same time I was reading about fairy tales in The Sleeping Beauty and Other Essays, circa 1955, by Ralph Harper. Harper was a reverend, a theologian, and a philosopher so his thoughts run deep. Harper led me to review classic illustrations in children’s books I had inherited, the My Book House series of retold nursery rhymes and tales from many lands, and Hans Christian Andersen’s stories with illustrations by Milo Winter. Vivid color. Enger’s novel opens in “boreal gloom” with the main character, middle-aged solitary Virgil, feeling lost in life and then nearly losing his life by plunging over a cliff into Lake Superior.

1923 Edition with the Hero Nearly Erased

Enger’s tale then follows Virgil’s seemingly modest quest: can he right himself in the “bad luck town” of Greenstone (a plain name that could evoke a magic gem) where his occupation is running an unprofitable movie theater? Virgil’s story occurs during a gray autumn and winter, un-blest seasons, yet it fits Harper’s definition of “enchantment” as “a mixture of the familiar and the unexpected.” After his rescue from dark waters, Virgil is unsettled by homesickness (though he’s technically home) and nostalgia. Rev. Harper endows “homesickness” and “nostalgia” with perennial meanings, and his words explain Virgil’s state of being. Homesickness is a “sign in man of his need for a true present”; it represents characters’ “last chance to return to the world of presence before they are lost forever in a world ruled by hate and alienation.” A fatherless teenager, a widow, and a jobless man may be even more prone to alienation than Virgil. Another Harper thought describes Virgil’s muted sense of himself as he thinks back on his past: “Through nostalgia we know not only what we hold most dear, but the quality of experiencing that we deny ourselves habitually.”

However, Virgil is lifted by the arrival of a mysterious foreigner, an old Norwegian kite-maker, “Rune,” looking for a son he’d never known. Rune’s kites give airy life to paper dogs and bicycles and to the people who fly them. There’s ordinary Midwest stuff throughout Virgil Wander with bad weather, taciturn characters, small-town politics. Yet Virgil’s attempt to claim a true present coincide with fairytale-like occurrences: the arrival of a stranger (Rune), the mystery of a lost prince (a baseball player), a woman who seems unobtainable (the baseball player’s wife), the return of a sinister figure (a devilish brother), a lost soul bewitched into dangerous misdirection, young innocents, a sentient animal (a raven), and a monster (a Great Lakes sturgeon).

Riding the North Wind, Nordic tale East O’ the Sun and West O’ the Moon

Virgil surrounds himself and a growing circle of friends with modern fairy talks in the form of contraband movie reels. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Ladykillers, We’re No Angels.

The plot of Virgil Wander has some action, comic twists, and life-threatening events. But the book’s animus comes from Enger’s pagan/Christian magic realism sustained by multitudes of stories. We think a fairy tale has a happy ending, but Harper believes people return to them because the narrative concerns “the relation of promise to defeat.” Virgil had felt defeated—can he still live up to a sense of promise? The tale ends where many begin, with a journey to origins.

Not exactly a spoiler: slight boy catches a nasty fish.

The post Fairy Tales, Lake Superior, Minnesota Writer Leif Enger, and a Fish appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

January 31, 2019

White Death and Hot Coffee: Minnesota, Frankenstein, Norway, Poe, Erdrich, and Fargo

The Deception: the sun gleams on luminous snow and makes the rimed trees shimmer. The sky is bright blue. Chickadees flit at the bird feeder. How welcoming! Step outside and you and your pathetic goose-pimples will die. Maybe not immediately if wrapped in dead fur and feathers. But heed the warnings because in Minnesota as I write the windchill is minus 50.

The Fact: for a week, the Midwest temperate zone is colder than the North Pole.

The Circumstance: Polar Vortex.

The Conclusion: Weather is murderous.

Deadly weather is no surprise in human history or literature. Extreme weather events and climates are sublime sources of death and transfiguration in eighteenth and nineteenth century literature. Coleridge’s albatross killer, the “Ancient Mariner,” was storm-driven into the polar south of “wondrous cold” where the ice “cracked and growled and roared and howled.” (In this weather, my joints do the same.) Mary Shelley’s Monster fled from the torture of human society toward the North Pole, and his creator Victor Frankenstein exhausted himself to death in cold pursuit.

Frankenstein by John Coleman Burroughs

Edgar Allan Poe wrote a strange novella–what what by Poe is not strange?–“The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket.” Poe also wrote “A Descent into the Maelstrom” set in the whirlpools off Norway’s Lofoten Islands within the Arctic Circle: by rights that narrator should have died of hypothermia. Arthur Pym heads in the opposite direction. His departure from shore is a drunken undertaking that eventually takes him to the Antarctic. After a murderous escapade with dark-skinned islanders, Pym travels into paradoxical heat and a peculiar whiteness that is a precursor of a Twilight Zone episode I can’t quite remember or a nuclear cloud. The white becomes a “white ashy shower,” “pallidly white birds,” a “veil,” a “cataract,” and a shrouded figure “the perfect whiteness” of snow. That phantasmagoric figure could be an escort into Hollow Earth theories or a hell where one must parse forever Melville’s Moby Dick. African American writer Toni Morrison has parsed the color peculiarities of Poe’s Pym and links to racism in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Novelist Mat Johnson plays with Poe and racial identity in his subversive homage, Pym.

Then there’s Jack London. I had to read “To Light A Fire” in middle school. Takeaway one: bleah. Takeaway two: dogs are smart.

For Minnesota writers, there’s O.E. Rolvaag (I can see his house from here) who sent Norwegian immigrant Per Hansa into a blizzard in Giants in the Earth. F. Scott Fitzgerald in “Babylon Revisited” has a drunken married couple leave in a snit a Paris bistro named “Florida.” Then the husband shuts the wife out in a snowstorm, the beginning of the end. Louise Erdrich opens her award-winning Love Medicine with the native woman June Kashpaw disappearing into an Easter snowstorm.

For a contemporary thriller, check out Brian Freeman’s Alter Ego which threateningly abandons a “summer man in a winter place.”

And we’ll always have Fargo. Watch for the weather report in the last seconds of this clip.

This blog has been powered by hot coffee.

Me on a Norwegian fjord, in JUNE.

The post White Death and Hot Coffee: Minnesota, Frankenstein, Norway, Poe, Erdrich, and Fargo appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

November 10, 2018

Mysteries, Farms, and the Incidents of Dogs in the Nighttime

FARM MYSTERIES

On the Job

Animals went missing. Those were the first mysteries of my life. When I was growing up in rural Maine during the 1960s, dogs and cats were free range to do their jobs. The dogs chased down rabbits and woodchucks, meaning fewer holes in the field to snag cows, ponies, and farm machinery. Cats were feral creatures of the barn and fields, keeping rodents out of the grain. The one time I caught sight of a barn rat from nose to tail I feared for the cats.

Unlike the silent, clue-providing dog in the Sherlock Holmes story, “Silver Blaze,” our farm dogs barked often in the dark of night. They may have been asleep in the kitchen or sheds, yet their ears would prick as raccoons stole into the garden or deer high-footed it into the corn. A single woof, a nail-clicking scrabble to the feet, and then woof-woof-woof until a human woke or the critters scared. Occasionally cows bewitched by the moon decided to take a midnight stroll down the middle of the road that split the farm. Cattle do not properly respect a fence and nose out its trick spots. The dogs’ barking alerted my father, who alerted us. We’d jump from bed in pajamas and tie on sneakers to chase cows into an enclosure.

A solitary bark, and my father would hush the dog. He would stand in the porch shadow and seek the white light sweeping the field. He’d quietly return inside to the rotary phone and call the game warden—deer jackers out and about aiming to shoot a blinded deer. If the light flicked too close, he would jump in the pickup and gun it down the road to scare off jackers before they mistook a Jersey or Guernsey for a deer or gleefully drove through barbed wire to spin ruts into the field

A wandering cow might jump a low gate to be discovered later in a neighbor’s field. The animal would ruminate, her eyes limpid and brown, her string of drool green. As strangers approached, she’d ignore proper bovine behavior to kick her hoofs and run in the wrong direction. A dry cow near her time might hide by the edge of the woods, and I then became a child in a Robert Frost poem “going out to fetch the little calf / That’s standing by the mother.” One or two vanished for good. We never suspected UFOs; the woods were dark and deep.

FERAL CATS

The Self-Domesticated

Cats with their greater numbers disappeared regularly. “Grandmother Cat,” the tabby breeder in the barn, had litters by toms who came and went in the night. Grandmother Cat would not let us touch her, though we could take her milk warm from the cow and pet her kittens. A few offspring chose domestication. This was especially true after a fluffy white house tom went rogue and a Persian blend appeared. One white kitten had a blue eye and a green one, familiar of a good witch. The self-chosen would scoot around an open screen door and dodge my mother’s discouraging foot and “shoo.” They too tended to disappear before reaching old age. Farm equipment would mow them down; distemper would flair up. Cats didn’t warrant vet care when rural folk could scarcely afford health care for themselves. There was a rabies scare—blame the raccoons. The state health department clamped down on the required dog vaccination and enlisted farm families and volunteers to catch cats and restrain them in onion bags. Vets could inoculate the yowlers right through the netting. Nothing’s as fast as a cat let out of a bag.

DOGS FOUND AND LOST

The Scot Original by Richard Ansdell

While farm dogs had the lazy habit of sleeping by the fire, on the doorstep, in the middle of the road, our prime mutt was swift—the mistress of the acreage, Wags. My father brought her home from another farm, and he had bundled her in his Dickies’ jacket (now called an Eisenhower because of its military style). A Border collie-mutt mix, she was an adorable brown, white, and caramel puppy. She liked being petted and sleeping on beds, but never cared to learn tricks and never tolerated a collar over her white ruff. (Her ID tags were stuck with family papers in the buffet drawer and tarnished with the silver.) Adult Wags answered to her jobs before she answered to us children. She patrolled the fields, scared off other dogs, gave strangers an evil eye. She answered to assignments of her own making. She bore litters of puppies because, in mother’s opinion at the time, spaying made females fat and lazy, and in the farm economy dogs were to be passed around. Few would pay for a dog, no normal person would pay for a cat. We gave the puppies away, mostly. There was “Vixen,” a fawn-colored pup who resembled the fox in a Dr. Doolittle illustration (we had my father’s old copies of the Hugh Lofting books). She played more than Wags and got along fine with her dam. Once my mother screamed at them when a doe bounded into the garden and the dogs took after her pell-mell through pasture and into woods. Dogs could be shot on sight for hounding deer to their death. Deer were rare then, and rarely seen because of prowling dogs had not yet overpopulated the suburbs in search of good schools. A trivia point: Maine fawns were the models for Disney’s Bambi. Our dogs did not kill any of Bambi’s friends that day and returned in ten minutes, unbloodied and unabashed.

During hay season when we were out in the trucks gathering bales, the dogs would follow and then chase down a scent. One evening Vixen, about two years old then, didn’t return for supper. Wags showed up near midnight, her coat a mat of burs. Vixen—she’ll come back, my mother said.

She didn’t. All of us looked and called whenever we went out into the fields for weeks, for months.

Wags had another litter of puppies. She had been penned when “in heat,” but the clever beast escaped. Her pups’ first food beyond mother’s milk was Pablum. Wags also brought her babies gory woodchucks, which they eschewed for the Pablum and playing with us. We kept a black curly-haired puppy, Trixie. I may have named her after Trixie Belden, the “girl detective” in the book series. Trixie, sweet and submissive, became my younger sister’s dog. In several years’ time, she disappeared as well. It was late March with spring uncertain about its estimated time of arrival. The woods had caches of snow, while the fields were muddy hillocks. I was fourteen and could walk the roads and check the ditches. I probed as far into the overgrown woods as I dared. The Maine woods had been logged generation after generation to become dense thickets of pines, tamaracks, birch stands, brush, and wild raspberry canes over old felled trees. Bogs spread here and there. Not penetrable.

Bambi’s sweetheart

We never found Trixie. I had suspicions. Had Wags lost her daughter-rivals on purpose? Was this canine treachery and betrayal? By that time, spaying had become routine and Trixie had gone under the knife, which my mother suspected damaged her instincts. (Do spay and neuter—no dog deserves to be unwanted and abandoned!) My mother also said people set traps for muskrats and maybe, what a shame, our pet had been trapped. My father said Certain People shoot strange dogs on sight—not a comfort. If Trixie had been hit by a truck, farm machinery, fox or other dogs may have hauled the carcass into the woods. My investigation ended, and green returned to the fields and new growth shadowed the woods more than ever.

When I was in my senior year of high school, aging Wags changed. She became terrified of thunderstorms and tried to dig her way through the cracked linoleum in the kitchen. She, who never cared to play, adopted squeaky toys from our babyhood—a rubbery pig, a soft plastic kitten. Wags dug a hole under an abandoned chicken coop and hid pig and kitten as if they were her puppies. She killed one last woodchuck for them, which I had to haul away before it stank up the farm yard.

We never learned what happened to Vixen and Trixie. On a hot August afternoon, stashing hay away in the barn loft, we tripped over Grandmother cat, older than I was. She lay dried and dead where she had borne her kittens. Ancient Wags developed a cancerous tumor and was euthanized when my sister and I were in college. People dumped dogs on my parents: an Irish Setter gone mad with inbreeding; an epileptic Saint Bernard who had to be euthanized because in a fit his powerful jaws might clamp on an arm; another Saint Bernard, Barrie, who begged for more attention that my bone-tired parents could give. After Barrie’s death, my parents were dogless. Until a mutt, German shepherd in the blend, showed up in the farmyard. Just hanging, threatening no one. My mother couldn’t stand the idea of not feeding him and called him Stray. Stray made himself welcome with his benign presence. When my father began to decline with Parkinson’s, he took pleasure in laying his heavy hand on Stray’s head.

Stray of unknown origins—the calmest dog the farm had known—would spend his warty dotage inside by the woodstove. As for the longest-lived, Wags and Grandmother Cat, they survived the nighttime. They kept their secrets. They were mysteries to us.

Farm dogs don’t have Mickey Mouse blankies.

The post Mysteries, Farms, and the Incidents of Dogs in the Nighttime appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

September 13, 2018

Adolescence, Social Media, Cyber-bullying, and Scene Stealing

The internet seems a custom fit for the adolescent brain: it is instantly receptive to impulses, secrets told beyond the hearing of adults, silly truth or dare games. Adolescents can find through social media the paradoxical assurance that a) no one has ever felt the way they do, they’re special; b) someone else has felt the way they do, they’re not alone.

But we stolid grownups have fearfully witnessed how social media sites enable children’s brief impulses to spin out of control, become abused, go viral. That, in turn, enables cyber-bullying and predatory behavior. The internet taketh away, and the internet giveth: parents and teachers can search the web for assistance in helping children who have been traumatized through social media.

I am not an expert in social media’s impact and offer no psychological advice. If I tried to give technical advice, it would be outdated the second I finish this sentence. However, I did research cyber-bullying and internet stalking to write Where Privacy Dies. In the novel, digital devices expose an adolescent girl, Haley Haugen, to mortal danger.

Danger, Haley Haugen!

What I can say without spoilers is that Haley is a scene-stealer. I did not base her on me in middle school except like her I had (emphasis on “had”) an affinity with math. I was the kid with glasses who finished the math homework first and was sent to the library to educate herself (small school, not much for competition, not much for beefcake either). Haley’s in middle school, surrounded by frenemies, and she knows she’s smarter than the average adult. She talks circles around Detectives Erik Jansson and Deb Metzger, and they’re no dummies. Haley has energy, she has attitude, she has whip-long hair and legs that run fast. She knows the web is “stalker-net.” When Haley returns to school after a mysterious absence, she bumps into Braden, a real cutie, and he teases by calling her a bully—how hot is that! Haley also learns that she has missed “the workshops on how not to be a bully.” She is dubious when it’s explained to her that “everybody was supposed to feel good about everybody,” like all the time.

Haley is not going to feel good about everybody, because somebody means her harm. It gets very very scary, and I’ll leave it to you to find out why.

The post Adolescence, Social Media, Cyber-bullying, and Scene Stealing appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

August 12, 2018

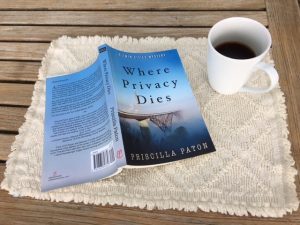

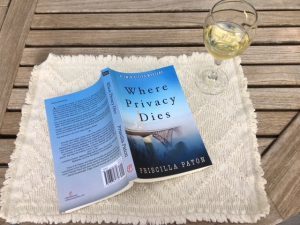

Book Launch: Publication and Party

This is the week when my family and friends gather to celebrate the publication of my mystery, Where Privacy Dies. It is a celebration of the community support it takes for a book to come forth from an author’s hand, and there’s nothing like the feeling of holding the actual thing in hand—joy. And the tremendous relief that the project, with its attendant hair-pulling, excessive coffee consumption, and procrastination spells, is finished. The hardest thing about writing a book is finishing it. Or is starting the hardest? Sorting out the middle? It’s all hard, and fun, and hence the party.

Not that authors regard their offspring with unmixed pride.

“Thou ill-formed offspring of my feeble brain,” Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet wrote of her poetry collection. While Anne stayed busy with her family duties in colonial Massachusetts, her brother-in-law saw that in 1650 her book was published in England under the title, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. Anne endeavored to write while mothering eight children and struggling with the conflict between her love of life and Puritan teaching to forswear earthly pleasures for immortal redemption. She wrote poems that praised Queen Elizabeth while she also had to demonstrate that her writing did not lead to neglect of her husband. (My husband cooks for me and I have the servant of the internet.) Despite her witty protestations, Bradstreet’s brain was far from feeble.

But authors often fret about their offspring. What kind of lives will they lead in imagination of readers? That’s the wonder of books. They live and breathe when read. I wish for Where Privacy Dies and its detectives Erik Jansson and Deb Metzger a long exciting life. Skol to Erik and Deb.

I am grateful to my family and friends for their support of my own feeble brain. I owe much to the inspiration and assistance of these organizations: The Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis; Mystery Writers of America; Sisters in Crime; and the Twin Cities Chapter of Sisters in Crime. I am grateful for the crucial guidance and opportunity to create the Twin Cities Mystery series provided by Coffeetown Press.

Back to the party: the photos provide some suggested pairing of book and beverage, from the coffee favored by Scandinavian Noir, the wine of the elegant amateur sleuths, and the bourbon of the hard-boiled. Drink responsibly to solve the crime.

Next time I’ll remember the Aquavit.

The post Book Launch: Publication and Party appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

July 21, 2018

Branding, Public Relations, Reputation Management, and Mysteries

What is your brand, and is it protected? I grew up believing my brand was “me” and I didn’t have to do much about it except be “me.” The “me” brand can change: the photo shows an old one.  But everyone’s experienced how being yourself can be challenging and people around you might see, or claim to see, a very different being when they look at you. Just-being-me has become a brand to be managed and shielded from distortion and outright lies. Have you checked outsiders’ comments on your social media lately?

But everyone’s experienced how being yourself can be challenging and people around you might see, or claim to see, a very different being when they look at you. Just-being-me has become a brand to be managed and shielded from distortion and outright lies. Have you checked outsiders’ comments on your social media lately?

If your brand includes a public persona connected with business, entertainment, or politics, you must engage Public Relations and Reputation Management. You don’t belong to you anymore but to your handlers and the public. This can be enormously profitable if you want to hide a devil within and display an angel without. Think Machiavelli, Orwell’s Animal Farm, Jekyll and Hyde, Dorian Gray, and a current public figure of your choice. Reputation laundering has built-in mysteries.

To write Where Privacy Dies, I looked into opposition research, reputation doctoring, and risk management. These strategies can legitimately benefit the individual and the public. The response to the Tylenol murders in 1982 are held up as an example of a corporation, the media, and law enforcement acting together to track down who had taken bottles of the pain reliever from drugstore shelves to lace them with poison. One outcome was the development of tamper-proof caps and reassurance that Tylenol was safe again. Reputation management during crises can cover up all kinds of misdoing. Think of Volkswagen lying about their vehicles’ emissions or Russia using Facebook to meddle in U.S. elections, as reported by USA Today. Also see BusinessInsider’s list of Corporate PR disasters. I wish I could say that The New Yorker writer Ed Caesar read an advance copy of Where Privacy Dies. He did his own excellent research to expose a PR firm, its equivocating founder, and a company seeking to influence a government in “Reputation Laundering”.

It’s fun in fiction to have absolutely delicious villains, and reputation management offered itself. And good luck with your brand.

The post Branding, Public Relations, Reputation Management, and Mysteries appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

July 11, 2018

Food: What Do Sleuths Eat

Fight and flight requires fuel. The pursuit of murderers requires strength. Those who investigate must feed their appetites. What will my detectives Erik Jansson and Deb Metzger consume so they can dodge death’s harvesting?

Noir private eyes, the Sam Spades and Philip Marlowes, survive by downing hard liquor and bad coffee. Hardboiled doesn’t refer to eggs, though the hardboiled may shove down eggs as flipped at a greasy spoon. Suspects and clients, like Lauren Bacall as Vivian Rutledge in the film version of The Big Sleep, drink their high-proof lunch. The genre takes corruption to the gut. For noir cocktails see: https://strandmag.com/cocktails-with-philip-marlowe-sam-spade-and-bogart/

British sleuths across the pond enjoy fine wine, fine dining, and tea. Readers might prefer the dinner setting of the well-to-do with Dorothy Sayers’ gourmand, Lord Peter Wimsey.  There is The Lord Peter Wimsey Cookbook with recipes for tomato sandwiches, genuine English grass (asparagus?), and steak-and-kidney pie.

There is The Lord Peter Wimsey Cookbook with recipes for tomato sandwiches, genuine English grass (asparagus?), and steak-and-kidney pie.

Rex Stout in his Nero Wolfe series is acclaimed for fusing the hardboiled investigator with the armchair sophisticate. Dining matters enormously to the enormous Wolfe. Menus as created by in-house cook Fritz Brenner include terrapin stew, planked porterhouse steak, vitello tonnato, and beer to clear the mind. Meanwhile, Wolfe’s field agent Archie Goodwin drinks milk for his muscles, eats pie and more pie, and tosses back the occasional highball. There is a cookbook, The Nero Wolfe Cookbook by Rex Stout. By the way, a number of people in the Wolfe series die by ingesting poison.

Where to eat becomes a problem not merely of hunger but of justice when there’s discrimination. Walter Mosley, creator of the Easy Rawlins mysteries, writes of the desegregation dining counters and his African-American father finally enjoying a taste of “freedom” and a tuna melt at a formerly whites only café. There is an unexpected incident, not racist but tragic. See http://www.waltermosley.com/2016/06/.

It’s challenging to read a Louise Penny novel without becoming hungry every third page. Her Inspector Gamache, a big man with the girth that accompanies middle age, goes to the Quebec village of Three Pines not only to solve murders but also to savor croissants and delicious coffee, and later wine and homemade stews at Olivier’s Bistro. Neighbors have potlucks with crusty bread. French Canadian Pea Soup, yum! There is a collection, but you have to sign up for publishing notifications to receive it: The Nature of the Feast: Recipes from the World of Three Pines, by Louise Penny.

In Venice, Donna Leon’s Commisario Guido Brunetti eats well. He doesn’t generally need energy to run hard or scale walls, but while on the case he meets people for meals and coffee, including caffe corretto, black coffee and grappa. Brunetti’s mouth-watering evening dinners (liver and onions, golden polenta) are prepared at home by his wife Paola, a Henry James scholar and as expected in Italy, an accomplished chef. There is a cookbook, Brunetti’s Cookbook.

Side note: I have a Soren Kierkegaard cookbook: either the recipes are good or not.

What will my detectives eat? Erik Jansson and Deb Metzger are Americans in a to-go culture. They’re employees and not employers, so Nero Wolfe’s nearly inviolable meal schedule is right out. They eat on the run, in a car, when they can. They’re surrounded by fast food options. However, they were Iowa-raised on wholesome goodness (high fructose corn syrup is a local product), and the Twin Cities offers inventive tasty choices, from steakhouses to vegan delights. Betty Crocker was “born” there, thanks to Washburn-Crosby milling which evolved into General Mills. Big Ag and small farms spread throughout Minnesota. Corn, soy, rhubarb, heirloom tomatoes. Hot dish. Will the detectives be daring in their culinary pursuits or play it safe? In many things they are Midwestern modest, but not in their appetite. Erik and Deb are tall people moving often and moving fast. What will they eat?

The post Food: What Do Sleuths Eat appeared first on Priscilla Paton.

May 2, 2018

Welcome

Welcome to the fictional world of Twin Cities Mysteries, with Detectives Erik Jansson and Deb Metzger.

If you’ve read this far, you trust words. Should you? I once trusted words. As a reader/teacher/scholar, I put my faith in them. As a mystery writer, I put my faith in them differently. I trust that words will misdirect, deceive, and hide desperate deeds and motives.

As we’ve witnessed, the digital revolution has made information readily available and advanced public and personal relationships. We depend on it to foster the ties that bind. (I can’t go a day without logging in.) The digital realm has also been a boon to the arts of deception and prevarication. Any of us can lie online, and others can lie about us. If we share truths, make corrections, will they be heard? To help with the tangle of information presented to us and about us are publication relation firms, image doctors, and reputation repairers. We turn to these specialists to make things right for us. (Or we turn to them to hide what we want to keep hidden.) We trust them to put our best selves forward. But what if that trust is betrayed? That broken trust is at the core of WHERE PRIVACY DIES. And remember, you’re only as safe as your encryption.

A word about the setting: Minnesota and the greater Minneapolis/St. Paul area is the backdrop. You do not have to be familiar with the region to follow the paths of the detectives. If you are familiar, you’ll recognize some geographical features, neighborhoods, and highways. Other elements are fictionalized, such as the Greater Metro Investigative Unit and its offices. What is real is the presence of water—the lakes, the Minnesota River, Minnehaha Creek, and the Mississippi River not yet mighty but gaining power as it flows through the cities. The corresponding wetlands are rich with wildlife and vast—places where a body could be lost. . .

Trust me, this will be fun.

The post Welcome appeared first on Priscilla Paton.