William Peace's Blog, page 9

January 27, 2024

Rarely Used Power Words

There is a list of 30 English words which are rarely used, powerful, and should be available to any writer appearing in the June 22, 2023 issue of Literature News and contributed by Alka. I think this is quite a good list, because all of them have a clear, crisp meaning, and while they may be rarely used, they aren’t obscure. Interestingly, none is an adverb. How many are familiar?

1. Abstruse (adj.): Difficult to understand; obscure.

Sentence 1: The professor’s abstruse lecture on quantum physics left the students bewildered.

Sentence 2: The book contained an abstruse passage that required multiple readings to grasp its meaning.

2. Acrimonious (adj.): Harsh in nature, speech, or behaviour.

Sentence 1: The divorce proceedings became acrimonious as the couple fought over their assets.

Sentence 2: The debate turned acrimonious as the politicians exchanged personal insults.

3. Alacrity (n.): Willingness to do something quickly and enthusiastically.

Sentence 1: Sarah accepted the job offer with alacrity, excited to start her new role.

Sentence 2: The team responded to the coach’s halftime pep talk with renewed alacrity on the field.

4. Ameliorate (v.): To make something better or improve a situation.

Sentence 1: The doctor’s treatment plan ameliorated the patient’s symptoms and enhanced their well-being.

Sentence 2: The charity’s efforts to provide clean water to the village ameliorated the living conditions of the residents.

5. Assiduous (adj.): Showing great care, attention to detail, and perseverance in one’s work.

Sentence 1: The assiduous researcher spent countless hours in the lab conducting experiments.

Sentence 2: The author’s assiduous editing process ensured that the final manuscript was flawless.

6. Clandestine (adj.): Done secretly or in a concealed manner, often implying something illicit or forbidden.

Sentence 1: The spies met in a clandestine location to exchange classified information.

Sentence 2: The couple planned a clandestine rendezvous under the moonlit sky.

7. Conundrum (n.): A difficult or confusing problem or question.

Sentence 1: Solving the puzzle proved to be a conundrum even for the most experienced players.

Sentence 2: The ethical conundrum presented in the novel forced the protagonist to make a challenging decision.

8. Deleterious (adj.): Harmful or damaging to health, well-being, or success.

Sentence 1: Smoking has been proven to have deleterious effects on both physical and mental health.

Sentence 2: The company’s deleterious financial decisions led to its eventual bankruptcy.

9. Ephemeral (adj.): Lasting for a short period; transitory or fleeting.

Sentence 1: The beauty of cherry blossoms is ephemeral, as the flowers bloom for only a few weeks each year.

Sentence 2: The actor’s fame was ephemeral, as he quickly faded into obscurity after his initial success.

10. Equanimity (n.): Calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in difficult situations.

Sentence 1: Despite the chaos around her, she maintained her equanimity and approached the problem with a clear mind.

Sentence 2: The leader’s equanimity during the crisis reassured the team and helped them stay focused.

11. Esoteric (adj.): Intended for or understood by only a small group with specialised knowledge or interest.

Sentence 1: The professor’s lecture on advanced mathematics was esoteric, and only a few students could follow along.

Sentence 2: The book delved into esoteric philosophies that were beyond the comprehension of most readers.

12. Exacerbate (v.): To make a problem, situation, or condition worse or more severe.

Sentence 1: The hot weather exacerbated the drought, leading to further water shortages.

Sentence 2: His careless comments only served to exacerbate the tensions between the two families.

13. Fervent (adj.): Intensely passionate or enthusiastic.

Sentence 1: The artist had a fervent desire to create meaningful and thought-provoking artwork.

Sentence 2: The politician delivered a fervent speech that inspired the crowd and ignited their patriotic spirit.

14. Gregarious (adj.): Fond of the company of others; sociable.

Sentence 1: Mark was known for his gregarious nature and always enjoyed hosting parties.

Sentence 2: The gregarious puppy wagged its tail and eagerly greeted every person it encountered.

15. Idiosyncrasy (n.): A distinctive or peculiar feature, behaviour, or characteristic that is unique to an individual or group.

Sentence 1: John had the idiosyncrasy of wearing mismatched socks every day.

Sentence 2: The small coastal town had its idiosyncrasies, including a yearly festival dedicated to seashells.

16. Impervious (adj.): Not allowing something to pass through or penetrate; incapable of being affected or influenced.

Sentence 1: The fortress was built with thick walls that were impervious to enemy attacks.

Sentence 2: Despite the criticism, her confidence remained impervious, and she continued pursuing her dreams.

17. Languid (adj.): Lacking energy or enthusiasm; slow and relaxed in manner.

Sentence 1: After a long day at work, she enjoyed taking a languid stroll by the beach to unwind.

Sentence 2: The hot summer afternoon made everyone feel languid and drowsy.

18. Melancholy (n.): A feeling of deep sadness or pensive sorrow, often with no obvious cause.

Sentence 1: As she watched the sunset, a sense of melancholy washed over her, and she reflected on the passing of time.

Sentence 2: The hauntingly beautiful melody carried a tinge of melancholy that touched the hearts of all who listened.

19. Myriad (adj.): Countless or innumerable; a large, indefinite number.

Sentence 1: The garden was adorned with myriad flowers, each displaying its vibrant colours and delicate petals.

Sentence 2: The old bookstore housed a myriad of books, spanning various genres and eras.

20. Nebulous (adj.): Vague, hazy, or indistinct in form or outline; lacking clarity.

Sentence 1: The concept of time is nebulous, as it is difficult to define precisely.

Sentence 2: The artist’s abstract painting featured nebulous shapes and colours, allowing viewers to interpret it in their own way.

21. Obfuscate (v.): To make something unclear, confusing, or difficult to understand.

Sentence 1: The lawyer attempted to obfuscate the facts to create doubt in the minds of the jurors.

Sentence 2: The politician’s speech was filled with jargon and obfuscating language to avoid addressing the issue directly.

22. Panacea (n.): A solution or remedy that is believed to solve all problems or cure all ills.

Sentence 1: Some people view education as a panacea for societal issues and inequality.

Sentence 2: The new product was marketed as a panacea for ageing, promising to reverse all signs of wrinkles and fine lines.

23. Querulous (adj.): Complaining or whining in a petulant or irritable manner.

Sentence 1: The querulous customer was dissatisfied with every aspect of the service and demanded a refund.

Sentence 2: The child’s querulous tone annoyed the teacher, who asked him to speak with respect.

24. Reticent (adj.): Inclined to keep silent or reserved; not revealing one’s thoughts or feelings readily.

Sentence 1: Despite the intense questioning, the witness remained reticent and refused to disclose any further information.

Sentence 2: The usually reticent boy opened up to his best friend, sharing his deepest fears and insecurities.

25. Sagacious (adj.): Having or showing keen mental discernment and good judgment; wise and shrewd.

Sentence 1: The sagacious old man offered valuable advice based on his years of experience.

Sentence 2: The CEO’s sagacious decision to invest in new technology propelled the company to unprecedented success.

26. Taciturn (adj.): Reserved or inclined to silence; habitually silent or uncommunicative.

Sentence 1: The taciturn loner preferred solitude and rarely engaged in conversations with others.

Sentence 2: Despite his taciturn nature, his eyes spoke volumes, revealing the emotions he kept hidden.

27. Ubiquitous (adj.): Present, appearing, or found everywhere.

Sentence 1: In today’s digital age, smartphones have become ubiquitous, accompanying people in every aspect of their lives.

Sentence 2: The fragrance of freshly brewed coffee was ubiquitous in the café, enveloping the space with its comforting aroma.

28. Vacillate (v.): To waver or hesitate in making a decision or choice; to be indecisive.

Sentence 1: She vacillated between accepting the job offer and pursuing further education.

Sentence 2: The committee’s members vacillated for hours, unable to agree on a course of action.

29. Wanton (adj.): Deliberate and without motive or provocation; reckless or careless.

Sentence 1: The wanton destruction of the historic monument outraged the community.

Sentence 2: The driver’s wanton disregard for traffic rules led to a dangerous accident.

30. Zealot (n.): A person who is fanatical and uncompromising in pursuit of their religious, political, or other beliefs.

Sentence 1: The religious zealot preached his beliefs on street corners, attempting to convert passersby.

Sentence 2: The political zealot refused to consider alternative viewpoints and dismissed any opposing opinions as invalid.

January 18, 2024

AI Wins Prize

An article in today’s RTÉ website titled: “Japan literary laureate unashamed about using ChatGPT” caught my eye. There is no author contribution shown.

“The winner of Japan’s most prestigious literary award has acknowledged that about “5%” of her futuristic novel was penned by ChatGPT, saying generative AI had helped unlock her potential.

Since the 2022 launch of ChatGPT, an easy-to-use AI chatbot that can deliver an essay upon request within seconds, there have been growing worries about the impact on a range of sectors – books included.

Lauded by a judge for being “almost flawless” and “universally enjoyable”, Rie Kudan’s latest novel, “Tokyo-to Dojo-to” (“Sympathy Tower Tokyo”), claimed the biannual Akutagawa Prize yesterday.

Set in a futuristic Tokyo, the book revolves around a high-rise prison tower and its architect’s intolerance of criminals, with AI a recurring theme.

The 33-year-old author openly admitted that AI heavily influenced her writing process as well.

“I made active use of generative AI like ChatGPT in writing this book,” she told a ceremony following the winner’s announcement.

“I would say about 5% of the book quoted verbatim the sentences generated by AI.”

Outside of her creative activity, Ms Kudan said she frequently toys with AI, confiding her innermost thoughts that “I can never talk to anyone else about”.

ChatGPT’s responses sometimes inspired dialogue in the novel, she added.

Going forward, she said she wants to keep “good relationships” with AI and “unleash my creativity” in co-existence with it.

When contacted by AFP, the Society for the Promotion of Japanese Literature, the Akutagawa award’s organiser, declined to comment.

On social media, opinions were divided on Ms Kudan’s unorthodox approach to writing, with sceptics calling it morally questionable and potentially undeserving of the prize.

“So she wrote the book by deftly using AI … Is that talented or not? I don’t know,” one wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter.

But others celebrated her resourcefulness and the effort she put into experimenting with various prompts.

“So this is how the Akutagawa laureate uses ChatGPT – not to slack off but to ‘unleash creativity'”, another social media user wrote.

Titles that list ChatGPT as a co-author have been offered for sale through Amazon’s e-book self-publishing unit, although critics say the works are of poor quality.

British author Salman Rushdie told a press conference at the Frankfurt Book Fair in October that recently someone asked an AI writing tool to produce 300 words in his style.

“And what came out was pure garbage,” said the “Midnight’s Children” writer, to laughter from the audience.

The technology also throws up a host of potential legal problems.

Last year, John Grisham, Jodi Picoult and “Game of Thrones” author George RR Martin were among several writers who filed a class-action lawsuit against ChatGPT creator OpenAI over alleged copyright violation.

Along with the Authors Guild, they accused the California-based company of using their books “without permission” to train ChatGPT’s large language models, algorithms capable of producing human-sounding text responses based on simple queries, according to the lawsuit.”

From my point of view, the use of AI to produce literature must sort out the copyright problem. When that issue has been resolved, using AI to write, or co-write, books will be accepted as commonplace, legal and ethical. We human beings have always adopted new technology, even dangerous technology, having found the good in it.

January 4, 2024

Fighting AI

There is an article in Monday’s issue of the Daily Telegraph concerning a lawsuit filed by the New York Times against Microsoft and Open AI that, on the face of it, is about imitating copyright news articles. But what is at stake is whether an artificial intelligence company could ‘train’ its software on the works of, say, Salman Rushdie, and then produce new Salmon Rushdi titles without paying the author any royalty. The article which bears the title “Silicon Valley’s mimicry machines are trying to erase authors” is written by Andrew Orlowski who is a technology journalist who writes a weekly Telegraph column every Monday. He founded the research network Think of X and previously worked for The Register.

Andrew Orlowski

Orlowski says, “Silicon Valley reacts to criticism like a truculent toddler throwing its toys out of the pram. But acquiring a bit of humility and self-discipline may be just what the child needs most.

So the US tech industry should regard a lawsuit filed last week as a great learning experience.

The New York Times last week filed a copyright infringement against Microsoft and Open AI.

The evidence presented alleges that ChatGPT created near-identical copies of the Times’ stories on demand, without the user first paying a subscription or seeing any advertising on the Times’ site.

ChatGPT “recites Times content verbatim, closely summarizes it, and mimics its expressive style”, the suit explains.

In other words, the value of the material that the publisher generates is entirely captured by the technology company, which has invested nothing in creating it.

This was exactly the situation that led to the creation of copyright in the Statute of Anne in 1710, which first established the legal right to copyright for an author. Then, it was the printing monopoly that was keeping all the dosh.

The concept of an author, a subjective soul who viewed the world in a unique way, really arrived with the Enlightenment.

Now, the nerds of Silicon Valley want to erase it again. Attempts to do just that have already made them richer than anything a Stationer’s Guild member could imagine.

“Microsoft’s deployment of Times-trained LLMs (Large Language Models) throughout its product line helped boost its market capitalization by trillions of dollars in the past year alone,” the lawsuit notes, adding that OpenAI’s value has shot from zero to $90bn.

With Open AI’s ChatGPT models now built into so many Microsoft products, this is a mimicry engine built on a global scale.

More ominously, the lawsuit also offers an abundance of evidence that “these tools wrongly attribute false information to The Times”. The bots introduce errors that weren’t there in the first place, it claims.

They “hallucinate”, to use the Cambridge Dictionary’s word of the year. Publishers who are anxious about the first concern – unauthorised reproduction – should be even more concerned about the second.

Would a publisher be happy to see their outlet’s name next to a ChatGPT News response that confidently asserts, for example, that Iran has just launched cruise missiles at US destroyers? Or at London?

These are purely hypotheticals but being the newspaper that accidentally starts World War III is not something that can be good for the brand in the long run.

Some midwit pundits and academics portrayed the lawsuit merely as a tactical licensing gambit.

This year both Associated Press and the German giant Axel Springer have both cut licensing deals with Open AI. The New York Times is just sabre rattling in pursuit of a better deal, so the argument goes.

In response to the lawsuit, OpenAI insisted it respects “the rights of content creators and owners and [is] committed to working with them to ensure they benefit from AI technology and new revenue models”.

However, the industry is worried about much more than money.

Take, for example, the fact that the models that underpin ChatGPT need only to hear a couple of seconds of your child’s voice to clone it authentically. AI does not need to return the next day to perfect their impression. After that, it has a free hand to do what it will with its newfound ability.

So, the economic value of a licensing deal is impossible to estimate beforehand. And once done, it cannot be undone. As one publishing technology executive puts it, “you can’t un-bake the cake”.

Previous innovations in reproduction, from the photocopier to Napster, were rather different beasts, as the entrepreneur and composer Ed Newton-Rex noted this week. Past breakthroughs were purely mechanical or technological changes. But this new generation of AI tools marry technology with knowledge.

“They only work *because* their developers have used that copyrighted content to train on,” Newton-Rex wrote on Twitter, since rebranded as X. (His former employer, Stability AI, is also being sued for infringement).

Publishers and artists are entitled to think that without their work, AI would be nothing. This is why the large AI operations – and the investors hoping to make a killing from them – should be getting very nervous. They have been negligent in ignoring the issue until now.

“Until recently, AI was a research community that enjoyed benign neglect from copyright holders who felt it was bad form to sue academics,” veteran AI journalist Timothy B Lee wrote recently on Twitter. “This gave a lot of AI researchers the mistaken impression that copyright law didn’t apply to them. “It doesn’t seem out of the question that AI companies could lose these cases catastrophically and be forced to pay billions to plaintiffs and rebuild their models from scratch.”

Would wipe-and-rebuild be such a bad thing?

Today’s generative AI is just a very early prototype. Engineers regard a prototype as a learning experience too: it’s there to be discarded. Many more prototypes may be developed and thrown away until a satisfactory design emerges. A ground-up rebuild can in some cases be the best thing that can happen to a technology product. There’s certainly plenty of room for improvement with this new generation of AI models.

A Stanford study of ChatGPT looking at how reliable the chatbot was when it came to medicine found that less than half (41 percent) of the responses to clinical conditions agreed with the known answer according to a consensus of physicians. The AI gave lethal advice 7 per cent of the time.

A functioning democracy needs original reporting and writing so that we all benefit from economic incentives for creativity. We must carry on that Enlightenment tradition of original expression.

Some may find such arguments pompous and any piety from the New York Times difficult to swallow. But there are bigger issues at stake.

A society that gives up on respect for individual expression, and chooses to worship a mimicry machine instead, probably deserves the fate that inevitably awaits.”

December 30, 2023

Censoring Imagination

Moira Marquis has an article dated December 7, 2023 on the Lit Hub website is which she talks about the importance of magical thinking for the incarcerated. She has a PhD and senior manager in the Freewrite Project at PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing program; she previously organized programs to supply books in prisons.

Moira Marquis

Moira writes: “In 2009 I was working with the prison book program in Asheville, North Carolina when I got a request for shapeshifting. I was shocked and thought it was funny, until I came to realize esoteric interests like this are common with incarcerated people.

Incarceration removes people from friends and family. Most are unsure of when they will be released, and inside prisons people aren’t supposed to touch each other, talk in private or share belongings. Perhaps this is why literature on magic, fantasy and esoteric ideas like alchemy and shapeshifting are so popular with incarcerated people.

When deprived of human intimacy and other avenues for creating meaning out of life, escapist thought provides perhaps a necessary release, without which a potentially crushing realism would extinguish all hope and make continued living near impossible. Many incarcerated people, potentially with decades of time to do ahead of them, escape through ideas.

Which is why it’s especially cruel that U.S. prisons ban magical literature. As PEN America’s new report Reading Between the Bars shows, books banned in prisons by some states dwarf all other book censorship in school and public libraries. Prison censorship robs those behind bars of everything from exercise and health to art and even yoga, often for reasons that strain credulity.

The strangest category of bans however, are the ones on magical and fantastical literature.

Looking through the lists of titles prison authorities have gone to the trouble of prohibiting people from reading you find Invisibility: Mastering the Art of Vanishing and Magic: An Occult Primer in Louisiana, Practical Mental Magic in Connecticut, all intriguingly for “safety and security reasons.” The Clavis or Key to the Magic of Solomon in Arizona, Maskim Hul Babylonian Magick in California. Nearly every state that has a list of banned titles contains books on magic.

Do carceral authorities believe that magic is real?

Courts affirm that magical thinking is dangerous. For example, the seventh circuit court upheld a ban on the Dungeons and Dragons role playing game for incarcerated people because prison authorities argued that such “fantasy role playing” creates “competitive hostility, violence, addictive escape behaviors, and possible gambling.”

A particularly strange example of banning magic can be seen on Louisiana’s censored list.

Fantasy Artist’s Pocket Reference contains explanations of traditional nonhuman beings like elves, fairies and the like. It also features drawings of these beings and some guidance on how to draw them using traditional or computer based art. The explanation for this book’s censorship on Louisiana’s banned list reads, “Sectarian content (promotion of Wicca) based on the connection of this type of literature and the murder of Capt. Knapps.” Captain Knapps was a corrections officer in the once plantation now prison, Angola, in Louisiana. Knapps was killed in 1999 during an uprising that the New York Times attributed to the successful negotiation of other incarcerated people for their deportation to Cuba at a different facility in Louisiana prior that year. It is unclear how this incident is linked in the minds of the mailroom staff with Wicca or this book—which is a broad fantasy text and not Wiccan per se. (Prison mailrooms are where censorship decisions are—at least initially—made).

As confused as this example is, what is clear is that these seemingly disparate links are understood by others within the Louisiana Department of Corrections since Captain Knapps’ death continues to be cited as rationale for why fantasy books are not allowed.

Is the banning of fantastical literature in prisons just carceral paranoia—or it is indicative of a larger cultural attitude that simultaneously denigrates and fears imagination? After all, prisons are part of U.S. culture which, despite a thriving culture industry that trafficks in magic and fantasy, nonetheless degrades it as lesser than realism. We see this most clearly in the literary designation of high literature as realist fiction and genre fiction like science fiction, Afrofuturism, magical realism as not as serious.

Magic’s status as deception and unreality is a relatively recent invention. Like the prison itself, it is a reform of older conceptions. In Chaucer’s time and place, ‘magic’ was a field of study. For example, in The Canterbury Tales, written in 1392, he writes, “He kepte his pacient a ful greet deel/ In houres, by his magyk natureel” when speaking about a doctor whose knowledge of plants was medicinal. Magic was connected to knowledge in Chaucer’s mind because of its connection with the Neoplatonic tradition, which acknowledged the limits of human knowledge. The known and the unknown were in a kind of relationship.

However, the Oxford English Dictionary notes, “Subsequently, with the spread of rationalistic and scientific explanations of the natural world in the West, the status of magic has declined.” Beginning with OED entries from the 1600s, “magic” becomes a term to designate manipulation of an evil kind.

At this time in Europe and its settler colonies, ‘magic’ became applied to a huge variety of practices increasingly seen as pernicious, from healing with herbs to rituals associated with nature spirit figures, like the Green Man and fairies, to astrology and divination. The diverse practices popularly labeled ‘magical’ were lumped together only through their association with intentional deception, superstition and error.

Writers like Ursula Le Guin have gone to great lengths to contest the supposedly firm divide between magic and reality. She argues that imagination is eminently practical and necessary:

Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom — poets, visionaries — realists of a larger reality.

For Le Guin, rejecting imagination is the ultimate collapse of the human social project.

Joan Didion’s conception of magical thinking as escapism is not far from this. The imagination that allows us mental respite from trauma is a bedfellow to the imagination that envisions our world unmoored to current conditions. There are so many issues that demand wild dreams to be addressed in more than shallow and inadequate ways.

It’s much simpler and less disruptive, of course, to deny dreams as unrealistic and to assert their danger. Imagination’s potential for disrupting systems already in place is clear. Those that cite this danger as a reason to foreclose imagination may even admit current systems imperfections yet, necessity. This may be the perspective of prison censorship of magical literature—commonly banned under the justification that these ideas are a “threat to security.”

Incarcerated readers say the censorship they experience oppresses their thoughts and intellectual freedoms. Leo Cardez says, “They [books] are how we escape, we cope, we learn, we grow…for many (too many) it is our sole companion.” Jason Centrone, incarcerated in Oregon, expresses exasperation with the mentality that sees magical thinking as threatening: “Or, lo! The material is riddled with survival skills, martial art maneuvers, knot-tying, tips on how to disappear—like this.”

Banning fantasy is particularly pernicious. Regardless of how you view incarceration—as an existence in a degraded and injurious confinement, or the justifiable requisitioning of people who have done harm away from others—we should all agree that we want incarcerated people to be able to imagine otherwise. Whether it’s imagining themselves or systems differently, creativity of thought is a tool to build a better life for everyone.

Such foreclosure of the imagination, a preemptive denial of the possibility of alternatives are a death-knell for betterment both individually and socially.

We need more magic, not less.”

I agree with Moira: imagination is a vital part of our humanity.

December 24, 2023

Collaboration: Novelists & AI?

Debbie Urbanski has an article on the Lit Hub website dated December 8, 2023 in which she argues that novelists should embrace artificial intelligence.

Debbie Urbanski is a writer, nature lover, and human whose stories and essays have been published widely in such places as The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy, The Best American Experimental Writing, The Sun, Granta, Orion, and Junior Great Books. A recipient of a Rona Jaffe Writer’s Award, she can often be found hiking with her family in the hills south of Syracuse, New York.

Debbie Urbanski

Debbie says: “Let’s imagine, for the purpose of this essay, that the following statement is true: An AI writes a novel.

Actually, forget about the imagining. This is already happening. Today’s AIs—large language models (LLMs) specifically, like GPT-4—can write. If you’ve glanced at the headlines this year, you probably know this. They can write papers for high school students, they can write bad poetry, they can write sentences, they can write paragraphs, and they can write novels.

The problem is, for now, the creative writing that LLMs produce isn’t that great.

To demonstrate this point, I recently gave GPT-4 a few lines from my novel that describe a post-human world. Then I asked it to complete the paragraph. Here’s what it wrote:

The woods seemed to inhale, drawing in its myriad of lifeforms, coalescing into a pulsing organism. The gurgling creek was its veins, the trees its lungs, the moss and ferns, its skin. This realm thrived on its own rhythm, deaf to the clockwork of man-made time. Creatures great and small, predators and prey, living in an intricate ballet—well, you get the idea. If I were being kind, I would call these sentences overwrought and unpleasant.

So here’s what I really want us to imagine for the purpose of this essay: An AI writes a novel and the novel is good.

This is what a lot of people, and certainly a lot of writers, are angry and scared about right now. That AI, having been trained on a massive amount of data, including copyrighted books written by uncompensated authors, will begin writing as well or better than us, and then we’ll be out of a job. These concerns over intellectual property and remuneration are important but right now, it feels they’re dominating the discussion, especially when there are other worthwhile topics that I’d like to see added to the conversation around AI and writing.

Such as: how can humans and AI collaborate creatively?

Which brings me to a third possibility to consider: An AI and a human write a novel together.

In my first novel After World, I imagine humanity has gone extinct and an AI, trained on thousands of 21st century novels, has been tasked to write their own novel about the last human on Earth. When I began writing in the voice of my AI narrator in 2019, I had no idea that within a few years, artificial intelligence would explode into public view, offering me unexpected opportunities for experimentation with what, up until that point, I had been only imagining.

Some of the interactions I’ve had with LLMs like GPT-3, GPT-4, and ChatGPT have been comical. GPT-3 recommended some truly awful book titles, such as Your Heart Was A Dying Light In An Abyss Of Black, But I Lit It Up Until You Burned Bright And Beautiful, or Eve: A Love Story. (Eve is not in this novel, I explained. This didn’t seem to matter. It is just a cute play on words, replied GPT-3.) But many of my conversations with LLMs have been fascinating.

I’ve discussed with them about what AI would dream if they dreamed. We talked about the questions an AI might have about how it feels to be a human. We discussed what the boundary between AI and humans would look like if this boundary was a physical one. (An “ever-evolving, shimmering and translucent wall,” if you’re wondering.) We talked about why poetry comforts people, and we tried writing poetry and song lyrics together. We created so much bad poetry and so many bad songs.

But after days and days of so much bad writing, GPT-4 presented me with this pleading prayer which now appears at a turning point of my novel. To the embodiment of growth and expansion, / To the embodiment of purpose and fulfillment. / To all these entities and more, I humbly offer my plea, / Grant me the strength to manifest my desires…

One can certainly reduce these sorts of exchanges to my typing in prompts and the LLMs responding to those prompts, but what I’ve experienced feels like a much more collaborative process, more of an active conversation that builds on previous interactions. In a way, when we talk with GPT-4, we’re talking to ourselves. At the same time, we’re talking to our past, to words we’ve already written or typed or said. At the same time, we’re talking with our future, portions of which are unimaginable. As a writer, I find that the most exciting of all.

Here are a few other examples of human-AI collaboration that leave me optimistic:

1. “Sunspring”“ (2016)

A short film directed and acted with grave seriousness by professional humans but written by Benjamin, a LSTM recurrent neural network. The writing is surprising, surreal, and beautiful. I’ve watched this film more times than I’ve watched any other. I find it both weird and moving. It features one of the prettiest songs I know, “Home on the Land,” written by Benjamin but sung and scored by the human duo Tiger and Man. From the lyrics: I was a long long time / I was so close to you / I was a long time ago. (Interesting to note that “Zone Out,” Benjamin’s much less collaborative 2018 film that he wrote, acted in, directed, and scored, doesn’t have nearly the same emotional impact as his more collaborative work, despite the fact that the technology had advanced in the two intervening years.

2. Bennet Miller’s exhibition at Gagosian (2023)

Miller, a Hollywood director, generated more than 100,000 images through Dall·E for this project. The gallery show displayed 20 of them. When I first saw these photographs in March 2023, I couldn’t stop looking at them. I still can’t look away. I find them haunting, existing on the edges of documentary and fiction and humanness, suggesting a past and memories that didn’t happen but nonetheless was recorded.

3. Other Dall-E’s collaboration with artists (ongoing)

In particular, check out Maria Mavropoulou’s work on “A self-portrait of an algorithm” and “Imagined Images”; everything August Kamp is doing, including documenting the worlds of her actual dreams with ChatGPT and Dall·E; and Charlotte Triebus’ Precious Camouflage, which examines the relationship between dance and artificial intelligence.

I worry that we’re forgetting how amazing this all is. Rather than feeling cursed or worried, I feel lucky to get to be here and witness such a change to how we think, live, read, understand, and create. Yes, we have some things to figure out, issues of training, rights, and contracts—and, on a larger level, safety—but I think it’s equally important to look up from such concerns from time to time with interest and even optimism, and wonder how this new advance in technology might widen our perspectives, our sense of self, our creativity, and our definition of what is human.”

December 16, 2023

Ending a Short Story

Peter Mountford has some excellent advice on how to end a short story in his article of February 12, 2023 on the Writers Digest website.

Peter Mountford is a popular writing coach and developmental editor. Author of two award-winning novels, A Young Man’s Guide to Late Capitalism and The Dismal Science, his essays and short fiction have appeared in The Paris Review, NYT (Modern Love), The Atlantic, The Sun, Granta, and elsewhere.

Peter Mountford

Peter says, “Many of my students and clients spend years working on a debut novel, only to discover that to get a literary agent’s attention they need to publish something—maybe a few short stories in literary magazines. But writing a great (or even publishable) short story isn’t easy.

Faulkner famously said every novelist is a failed short story writer, and short stories are the most difficult form after poetry. There’s some truth to the idea that short stories have more in common with poems than novels. Novels are more labor intensive, for sure, but there’s something fluke-ish and rare about a perfect short story.

Short story writing hones your craft in miniature, without having to throw away multiple “practice” novels, which can be—speaking from experience—uncomfortable and time-consuming.

The best short stories are remembered for their ends, which “leave the reader in a kind of charged place of contemplation,” according to Kelly Link—a Pulitzer finalist whose fifth collection of stories, White Cat, Black Dog, will be out soon.

David Means, author most recently of a new collection of stories, Two Nurses, Smoking, said, “A good ending doesn’t answer a question. It opens up the deeper mystery of the story itself. There isn’t room in a short story to do anything but leave the reader alone with the story.”

“I want an ending that feels like a punch in the gut that I wasn’t expecting but totally deserved,” says Rebecca Makkai, author of Pulitzer Prize finalist The Great Believers, and whose stories have had four appearances in the Best American Short Stories series.

What Is an Ending?Before we get to techniques, there’s the question of what we mean by the “end” of a story? Is it the last scene, or the climactic turn, or the actual final sentences?

In the days of O. Henry’s short stories, the climax, last scene, and final sentences were all largely the same, and featured an unlikely plot twist accompanied by direct moral instruction. “The Gift of the Magi” concludes with the husband and wife realizing that in an effort to give their spouse the perfect small gift they’ve each spoiled receipt of their own small gift. In the final paragraph, O. Henry awkwardly steps in to explain the moral of the story, how they “most unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest treasures of their house.” It feels hoary and antique to a modern reader.

Now, the big climactic moment often happens two-thirds of the way through the story, not on the last page, and the story’s moral or lack thereof must be deduced by the reader.

Consider ZZ Packer’s amazing “Brownies,” where the story’s confrontation builds from the first sentence, when one Black Brownie troop hatches a plan to “kick the asses of each and every girl” in another white Brownie troop, after possibly overhearing a racial slur.

About two-thirds through the story, right as they’re about to fight, it’s discovered that the white troop is mentally disabled. But the story doesn’t end there with a moral quip, as it would have 100 years ago. In the few pages that follow, on the bus home after the confrontation and its fallout, the narrator describes her father, who once asked some Mennonites to paint his porch. “It was the only time he’d have a white man on his knees doing something for a Black man for free.”

Another girl asks her if her father thanked them. “‘No,’ I said, and suddenly knew there was something mean in the world that I could not stop.” The reader sees now that this story is about how terrible treatment can lead to anger and further cruelty.

This part of the story, the bus ride after the action, is what you might call a coda, and the coda often contains the real “magic” in a contemporary story. The word coda comes from music, where it means an ending that, according to the dictionary, stands “outside the formal structure of the piece.”

In the coda—and not all contemporary stories have a coda, but most do—the writer helps the reader identify meaning without stating it as bluntly as O. Henry did. By leaving the work of interpretation to the reader, the writer allows for variety in how we might interpret the story. With ambiguity, the reader can continue to think about the story.

The Process: To Plan or Not to PlanJohn Irving famously (supposedly?) writes the last line of every novel first, and then finds his way there.

Similarly, Kelly Link wants to know the end before she starts—it’s the least shiftable piece for her. She mulls a story over while swimming and walking. Having an ending in mind makes her more “surefooted about where to begin,” and what choices to make early in the story.

When editing or teaching, she suggests that a writer’s first idea for an ending often might be too obvious, and the second merely less obvious. The third will be more innovative, or singular.

When friends are working on stories, she enjoys kicking around ideas for their ends, going straight for some wild “‘bad idea’ that’s large and fun, and often goes somewhere strange or personal or interesting.”

On the other hand, Danielle Evans, whose second collection of stories, The Office of Historical Corrections, came out in 2020, said she can’t get excited about writing something unless she’s the first reader surprised.

Rebecca Makkai says she often has an ending in mind from the start, but “I very much hope I’m wrong. If I land right where I always thought I would, I’ve probably written a terribly obvious story.”

My own experience is that often when the story concludes in a way that is somewhat obvious or inevitable from the outset, there is even more of a burden on the writer to summon a brilliant coda and some stunning insights to wow the reader.

Tricks of the Short Story TradeWhat do you do when you’re stuck, don’t like your current ending, or didn’t plan your ending? Several simple techniques might open things up for you.

Trick #1: Jump in Time“I try to remember that the ending doesn’t have to stay in the same room or world or mode or timeframe as the rest of the story,” Makkai says. “These seismic shifts shake us loose from the world of the story and are very likely where we’ll find the story’s echoes and meanings.”

In Danielle Evans’ story “Snakes,” two 8-year-old cousins (one biracial and one white) are with their belittling, racist grandmother for a summer stay. The cousins get along, but at the climax the white cousin pushes narrator Tara out of a tree, almost killing her. The story could end there. Instead, “Snakes” jumps forward.

In her 20s, Tara has finished law school and likes to retell the story almost as entertainment. Her cousin is in a radically different place and has attempted suicide. When Tara visits her in a mental hospital, they’re kind to each other, yet their personalities and differing home lives sent them on radically different paths. The final paragraphs reveal that the narrator wasn’t pushed—she jumped from that tree, as a successful effort to get away from her grandmother. Her white cousin was left behind and endured a damaging, toxic relationship. The ending provides cues as to why their paths diverged, and the risks Tara took to escape.

You can also leap back in time. In Charles D’Ambrosio’s “The Point,” the story wraps up after the teenage narrator successfully and safely transports a drunk woman to her house. Then the coda: a flashback, the narrator coming upon his father after he’d shot himself in the head. It’s still a jump in time far away from the frame of the story but echoes an earlier time he couldn’t save someone.

To apply this approach, don’t be shy with time. Look for a big moment well in the future. Or, if the story has had few flashbacks, but the reader senses that the main character has a complex backstory, maybe you can go there to add another layer.

Trick #2: Change LensesMakkai points to Percival Everett’s hilarious and subversive “The Appropriation of Cultures,” as an example. Daniel, a Black man in South Carolina, decides to change how he sees the Confederate flag. He decides to treat it as a “Black Power flag,” then reinvents “Dixie” as a celebration of his own racial and cultural identity. Baffled racists are left floundering as Daniel appropriates the icons of their hate.

In the story’s final movement, the scope changes completely, pulling back to reveal the landscape from a more distant perspective. We leave Daniel’s story behind as the narrator shows other Black folks in Columbia, S.C. adopting the trend. We’re told the state’s white leaders decided to take down that flag—its meaning now inverted—from the state house.

To apply this to your own work, play with perspective—try stepping out of the confines of the story and looking at what might happen as a result if you pull back, or change the POV to an omniscient narrator. However, you can’t usually switch perspectives from one character to another. This tends to feel forced and jarring for the reader.

Trick #3: Make a Flat Character Three-DimensionalThis is a favorite of mine. Tobias Wolff’s “Bullet in the Brain” combines this technique with a swing to a new POV—many great stories use several techniques at once.

The unpleasant POV character is shot dead about two-thirds of the way through the story, and the story pivots to an omniscient narrator. The narrator now catalogues Anders’ memories that didn’t flash in the final milliseconds of his life—memorizing hundreds of poems so that he could give himself the chills, seeing his daughter berating her stuffed animals, and so on.

Crucially, these unrecalled memories transform Anders from unlikable flat character to someone complicated. By the time the bullet leaves his “troubled skull behind, dragging its comet’s tail of memory and hope and talent and love into the marble hall of commerce …” readers are moved to tears.

Interestingly, the character in Wolff’s story has no epiphany, he doesn’t evolve. Only the reader’s understanding of the character changes. As novelist and short story writer Jim Shepard once wrote: “a short story, by definition, does have a responsibility in its closing gestures, to enlarge our [the reader’s] understanding.”

To do this, look for a character in the story who might be fairly important—possibly an oppositional character to the protagonist—but remains flat or slightly cliché. The mean jock. The shy nerd. Find a situation at the end where they’re acting in a way that complicates the reader’s sense of them. You can also see this in the final scene of “Brownies,” when the shy narrator and her shy friend become the center of attention.

Trick #4: Shift From Summary to SceneDonald Barthelme’s surreal, darkly funny “The School” is told primarily in summary, narrated by a teacher describing a school year marked by death. His students try to grow orange trees but the trees wither; then the snakes die, along with herb gardens, tropical fish … the class’s puppy. The deaths are increasingly surreal and funny.

No scenes occur until the final page, when Barthelme “lands,” finally, in a scene, where the students grill the teacher with amusing and improbable over-eloquence over the meaning of death and life. The students press him for a demonstration regarding the value of life and love; he kisses his teaching assistant on the brow, and she embraces him (yes, the story is very strange). A new gerbil walks into the room to enthusiastic applause.

After reading “The School,” I borrowed this technique—summarizing a broad period of time, and then landing in a pivotal scene—for my story “Two Sisters,” which is unreliably narrated by a young man who hangs around with a wealthy jet-setting group. After summarizing the preceding year, the story shifts to scene where one of the rich kids says he’s no longer welcome—they find him too weird. Overwhelmed, he tries to attack her, but she gets away. He’s literally and metaphorically stranded in the wilderness.

The story couldn’t be more different in style and tone from “The School,” but the technique is the same.

To make this technique work, just look for a story that has a conversational style and covers a lot of ground, in terms of time. A narrator who seems to be chatting away about a period of time, and then drop them into a moment which animates and changes the situation they’ve been describing.

Trick #5: Return to an Object or Situation Mentioned EarlierIf a student or author who Kelly Link is editing is struggling with the end to their story, she suggests looking to “the beginning of the story, to see what was being promised there.”

Often, a story closes by returning to an object, situation, or idea mentioned early in the story. Kirstin Valdez Quade’s remarkable story “Nemecia” describes the narrator’s cousin’s shattered doll on the first page. By the story’s end, the narrator has been safeguarding this doll for half a century. She calls her now-elderly cousin to ask if she wants the doll, which the reader can now see symbolizes the cousin’s harrowing childhood. The cousin says she doesn’t even remember the doll.

Asked how she came up with this ending, Quade explained the initial draft was about 50 percent longer. An editor pointed out a sentence that would become the story’s last line, which echoes the doll’s shards. She took the advice, and “remembered the doll from the beginning and saw the opportunity.” Once she saw the proper end, she cut away everything unnecessary throughout, leaving this unforgettable conclusion.

To do this, add things to a story that you don’t know how or if you’ll use later. If they don’t end up being useful, cut them, but it’s easier to find these opportunities if you’ve scattered potential reference points in the first half of the story.

Trick #6: If All Else Fails, Keep GoingDanielle Evans points out that she often writes a paragraph that could end the story, but then she keeps going, “and those extra beats are what open it back up and make everything more interesting.”

Means offers a similar recommendation—and clearly Quade did this with “Nemecia.” “When you’re starting out as a writer,” Means said, “you sometimes write past the ending and then have to go back and cut, finding the right place to let it stop,” he says. “It’s a horrible feeling, cutting your own work, a sort of self-amputation, like the hiker who has to cut off his own foot—stuck between rocks—to keep living. But the end result can be stunning. The reader wonders how you did it. You’ve covered your tracks.”

Wrapping It UpThe best short stories can seem miraculous, intimidatingly perfect. Ends so inspired that no mere mortal could ever come up with something like that. But people do it all the time.

Sometimes it’s just trial and error. Sometimes you have to overwrite, pile up the writing and then see what should be kept. Then again, as Evans said, if you can make it to the final third of a story, and the first two-thirds are right, then you can “find the ending on momentum.””

December 12, 2023

Seeing What a Child Sees

On The Epoch Times website, there is an article by Kate Vidimos, dated 2/11/2023 which illustrates how emotionally powerful a short story can be. Ms Vidimos describes a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne, the early nineteenth century American writer, about a walk he took with his young daughter.

Kate Vidimos is a 2020 graduate from the liberal arts college at the University of Dallas, where she received her bachelor’s degree in English. She is a journalist with The Epoch Times and plans on pursuing all forms of storytelling (specifically film) and is currently working on finishing and illustrating a children’s book.

Ms Vidimos writes: “Look! Do you see how that light shines on the pavement in the rain? It sparkles like magic and spreads its light, despite the dark clouds which seem to discourage it. Such is the world as seen through the eyes of a child.

In his short story “Little Annie’s Ramble”, Nathaniel Hawthorne encourages us to take a childish view of the world to refresh and simplify the sober, complex adult world. As he takes his daughter’s hand for a walk, Hawthorne shows how a child can lead us on a magical and wise journey.

Hawthorne takes his little 5-year-old daughter Annie by the hand to wander and wonder aimlessly about the town. They set out for the town-crier’s bell, announcing the arrival of the circus: Ding-dong!

From the beginning, Hawthorne notes the difference between himself and Annie, like the bell’s different notes (ding-dong). His adult step his heavy and somber (dong). Yet Annie’s step is light and joyful, “as if she is forced to keep hold of [his] hand lest her feet should dance away from the earth” (ding).

They journey along, looking at the different people, places, and things that present themselves to their view. Hawthorne moralizes and philosophizes about these different subjects, seeing the objects within the windows as they are, while Annie trips along dancing to an organ-grinder’s music and seeing in the windows her reflection.

Yet, as they pass along, Hawthorne’s mind grows more aligned with Annie’s. As they pass a bakery, they both marvel at the many confectionary delights in the window. He remembers his own boyhood, when he enjoyed those treats the most. As his daughter’s hand wraps around his own, childhood magic wraps around him.

But behold! The most magical place on earth for a child is the toy store. In its windows, fairies, kings, and queens dance and dine. Here, the child builds fantastical worlds that “ape the real one.” Here lives the doll that Annie desires so much.

Hawthorne sees Annie’s imagination weave stories around this doll. He thinks how much more preferable is the child’s world of imagination to the adult world, where adults use each other like toys.

They continue on and journey through the newly arrived circus. They see an elephant, which gracefully bows to little Annie. They see lions, tigers, monkeys, a polar bear, and a hyena.

The more they see, the more Hawthorne’s view adopts a childlike wonder. Just as Annie imagines the doll’s story, Hawthorne weaves different stories around the animals. The polar bear dreams of his time on the ice, while the kingly tiger paces, remembering the grand deeds of his past life.

Through this story, Hawthorne realizes that, though he can never truly return to his childhood, he can adopt his daughter’s wonder. Such a wonder-filled ramble teaches much wisdom.

Others will discount such a ramble as nonsense. Yet Hawthorne exclaims: “A little nonsense now and then is relished by the wisest men.”

A child’s sense of wonder can enable one to see light in the air, beauty in the normal, and magic everywhere. The world is a place of wonder and magic, and a place of “pure imagination,” so look for it and you will see it.”

December 3, 2023

Romance with Unhappy Ending?

Hannah Sloane has an article ‘Happy Endings Redefined: Why there Should Be More Books about Breakups’ on the Lit Hub website dated 10 November 2023. She advocates more novels about breakups.

Hannah Sloane was born and raised in England. She read history at the University of Bristol. She moved to New York in her twenties and she lives in Brooklyn with her partner, Sam. The Freedom Clause is her debut novel.

Hannah Stone

Hannah says: “Years ago, sitting in a restaurant with my boyfriend at the time and another couple, I watched as my boyfriend picked up the bottle of wine we’d ordered and refilled only his glass. I remember thinking: I’d like to be with someone who fills every glass on the table, and I don’t think that’s too big of an ask. I did not act on this observation. Instead, I added it to the steady drip of disappointments taking up residence in my anxious, overactive mind.

I know many women who have stayed in relationships a beat too long, or even years too long, unhappily embracing the philosophy that a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Not every bird, however, is worth holding onto, especially the ones that make us feel stuck or anxious.

And yet sometimes we hold on regardless, treading water in relationship purgatory, unable to take a leap of faith into the unknown. Whenever I speak to a friend facing this dilemma, invariably she will say how scary the idea of being single again is. Scary is always the word used. Why is this?

It’s cruel and sexist, but it’s true: the single woman in her forties is not a celebrated figure. When I ended a committed relationship in my mid-to-late-thirties it felt like an enormous personal failure. I felt I was going against the grain of societal pressure which dictates that the women we aspire to be in our thirties, the women who are truly accomplished, are married or in relationships headed in this direction (and staggeringly, this pressure begins in one’s twenties).

And yet why is being single perceived as such a failure? Why can’t extricating ourselves from a relationship that isn’t serving us well be treated as a giant celebratory step that deserves a party, a cake, streamers, and the popping of champagne? Moreover, how about from a young age we condition women to value self-growth and taking risks over reaching yet another relationship milestone?

I read How To Fall Out of Love Madly by Jana Casale. I am going to simplify the plot of this terrific book crudely to prove a point here: it’s a book in which the women we follow are embroiled in relationships with men that are not serving them well, and they are much happier for it when those relationships end. My god, I want more fiction that leans in this direction, more fiction that makes this point loudly, emphatically. I want an entire wing of the library dedicated to literature about women extricating themselves from relationships that aren’t serving them well.

I contemplated all of this as I set out to write my debut novel, The Freedom Clause. It’s about a young couple, Dominic and Daphne, who decide to open up their marriage one night a year over a five-year period. There are rules in this agreement, designed to protect them both from getting hurt.

But over the course of five years, only one of them adheres carefully to those rules, only one of them treats their relationship with the respect it deserves. And by the end of the novel, it is quite clear what Daphne must do, what choice she must make. I hope that choice is met with a celebratory fist pump by the reader.

I was writing the novel I wanted to read when I was feeling stuck and anxious. I was considering the relationships I had been in, and the relationships I had witnessed, as I plotted out the story of a young woman who has been raised a people pleaser, and whose journey of self-assertion in the bedroom ultimately plays out in other areas of her life.The market for romance novels is enormous, and will likely remain that way, but there is an alternative happy ending for women, one in which the protagonist chooses to prioritize her happiness without a neat romantic conclusion on the final page.

Because I wanted to write the book that women give to their best friend when it’s unequivocally time for that friend to end her crappy relationship. Because we need novels where the breakup is the happy ending, the cause for celebration, and we need literature that gives women permission to live their lives fully, on their own terms, by ignoring societal pressures and focusing on what they need.

The market for romance novels is enormous, and will likely remain that way, but there is an alternative happy ending for women, one in which the protagonist chooses to prioritize her happiness without a neat romantic conclusion on the final page. And by popularizing this decision in fiction, perhaps we can make it less scary for those contemplating it in real life. For there is something much scarier than being single, and that is the bird in hand preventing us from reaching out for the life we hoped for, the one we deserve, a life we can grasp if we let go of what’s holding us back and trust in the path ahead.”

It seems to me that Hannah is making a good point about the market for novels about failed romances. The difficulty is in creating a female character (or male for that matter) who needs the relationship, but who is also strong enough to begin again on her/his own, and in creating the ‘aftermath’ that is both credible and comfortable to the reader. Perhaps Hannah has done just that in her novel.

November 19, 2023

Book Banning

There are several news items relating to book banning, which is becoming a controversial topic in the USA. For example, there is this from Publisher’s Weekly dated 3 October 2023:

“The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has set a tentative schedule to decide whether a judge’s order blocking the state’s controversial book rating law, HB 900, should stand. But an administrative stay issued last week by a separate motions panel of the Fifth Circuit remains in force—meaning that the law is now in effect, putting Texas booksellers in a precarious position…

“Signed by Texas governor Greg Abbott on June 12, HB 900 requires book vendors, at their own expense, to review and rate books for sexual content under a vaguely articulated standard as a condition of doing business with Texas public schools. The law includes both the thousands of books previously sold to schools and any new books. Furthermore, the law gives the state the unchecked power to change the rating on any book, which vendors would then have to accept as their own or be barred from doing business with Texas public schools.”

and this from The Book Browse website dated 29 September 2023:

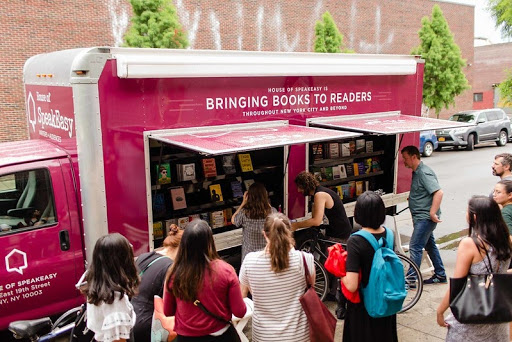

“In partnership with the Freedom to Read Foundation, PEN America, and the Little Free Library, Penguin Random House is launching the Banned Wagon Tour, which during Banned Books Week will travel across the South, stopping in communities affected by censorship, celebrating the power of literature, and getting books to the people who need and want them most. PRH called the Banned Wagon part of its “ongoing efforts to combat book banning and censorship, which includes legal actions, tailored support for various stakeholders, and advocacy for First Amendment rights.”

“The Banned Wagon will feature a selection of 12 books that are currently being banned and challenged across the country, distributing free copies (while supplies last) to event attendees in each city. The Banned Wagon will also drop banned books in Little Free Libraries along the tour route and make a book donation after each Banned Wagon event. The Banned Wagon will include material from the Freedom to Read Foundation about how to write letters to school boards and elected officials, as well as regional spotlights from PEN America highlighting books and challenges being banned in specific states.”

and this from the Shelf Awareness website dated 29 September 2023:

“Coinciding with Banned Books Week, which begins this Sunday, October 1, the New Republic will launch the Banned Books Tour 2023, aimed at “championing the First Amendment and combating censorship.” The bookmobile, a symbol of literary liberation, will visit states that have experienced some of the highest incidences of book censorship, including Texas, Florida, Missouri, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, and continue to operate through the month of October.

“The tour will start at the Brooklyn Book Festival this weekend, where, in partnership with House of SpeakEasy, the New Republic will accept book and financial donations at the SpeakEasy Bookmobile. All literature may be donated, with a preference for banned and challenged books. These books will be given away in communities on the tour where access has been restricted or limited.

“Launching a book festival on wheels is a huge new undertaking for us, and I can’t wait to hit the road to support the importance of reading, New Republic CEO and publisher Michael Caruso said. “It’s even more exciting that we can embark in time to support ALA’s Banned Books Week. The New Republic has been a leading defender of the First Amendment for over a century, and this is a new way to give people the tools to join the fight for the freedom to read.”

November 10, 2023

Gender Specific Dialogue

Here is an article from the Writers Digest website by Rachel Scheller dated 11 February 2023 in which she discusses gender differences in dialogue. She begins by saying, “Writing dialogue to suit the gender of your characters is important in any genre, but it becomes even more essential in romance writing. In a romance novel, characters of opposite sexes are often paired up or pitted against each other in relationships with varying degrees of complication. Achieving differentiation in the tones and spoken words of your male and female characters requires a careful touch, especially if you’re a woman writing a male’s dialogue, and vice versa.

“GENDER-SPECIFIC DIALOGUE

It’s difficult for a writer to create completely convincing dialogue for a character of the opposite gender. But you can make your dialogue more realistic by checking your dialogue against a list of the ways in which most writers go wrong.

“If You’re a Woman

Here’s how to make your hero’s dialogue more true to gender if you’re a female writer:

“If You’re a Man

Here’s how to make your heroine’s dialogue more realistic if you’re a male writer:

“Writing Realistic Dialogue: Exercises

Eavesdrop (politely) as real people talk. How do two women speak to each other? How do two men speak to each other? How do a man and a woman speak to each other?Can you guess the nature of each relationship? For instance, do you think the couple you’ve listened to is newly dating or long-married? On what evidence did you base your opinion?Read your dialogue aloud. Unnatural lines may hide on the page, but they tend to leap out when spoken.Listen to someone else read your dialogue aloud. Better yet, get a man and a woman to read the appropriate parts. How do the lines sound? How do they feel to the speakers?”

Rachel Scheller

I haven’t been able to find a bio of Rachel. Where the bio is usually inserted at the end of the article, it is always a member of Writers Digest staff with a different name. All I can say is that Rachel has written about a dozen articles for Writers Digest and some books.