William Peace's Blog, page 55

July 25, 2014

Subtlety

One of my learnings as I’ve been writing and reading other authors’ work is the importance of subtlety. Rather than spell out what has happened or what is going to happen, it is often better to imply and let the reader draw his/her own conclusions, or guess. Obviously, there are times when it is necessary to be explicit: for example, when an author wants to elicit strong feelings in the reader. But there can be a fine line between developing strong feelings about a character and the reader developing negative feelings about the book.

Sex is one area where I feel, now, that less is sometimes more. Presently, I feel that the use of explicit words can interrupt the reader’s attention, and force him/her to develop an explicit mental picture of what is happening. Depending on the reader’s reaction, the explicit picture may or may not be erotic, or enjoyable.

Here is an example of the more explicit approach from my first novel, Fishing in Foreign Seas:

He stepped into the shower and closed the door behind him. They embraced, luxuriating in the delicious feel of wet skin against wet skin. He redirected the shower head so that it did not spray into their faces. They began a long, sensuous French kiss, their hands wandering over each other. Caterina’s legs had drifted apart, and his fingers found her black curls and then her secret cleft. “Oh, Jamie, don’t stop.” Her hand found his erection, and began to stroke. They moaned into each others mouths, their hearts racing and their breathing erratic, as they clung more strongly to each other, their eyes closed. She became rigid and stifled a cry of release.

“Oh, yes!” he groaned, and she opened her eyes to see his semen disappear in the streaming water.

They kissed slowly and lovingly, holding each other close.

“Oh, God!”

“What a beautiful way to start the day!”

And here’s a sample from my latest novel, which will be sent for final editing next week:

“Mary Jo, I must have tried to visualise you as you are now a hundred times.”

There was a slight giggle. “I didn’t try to visualise. I tried to feel your touch and smell your body. Now, it’s so nice to be real.”

He run his hand slowly and repeatedly from her cheek to her knee, pausing at her breast, her navel and her mound. “God, you’re a beautiful woman!”

“Well I’m not, but I’m glad you think so. Let me see your scars.”

She raised herself to a sitting position. She giggled again. “Rob!”

“What?”

“You know perfectly well what.”

“What am I supposed to do about it?”

“Nothing right now. Maybe later. How many stitches do you have here?”

Another area where caution is required is in descriptions of violence. Violent scenes are sometimes necessary: they may represent an essential turning point in the plot; they may shed clarifying light on one or more of the characters, but too much clarity can turn the reader off.

Writing my latest novel, I discovered the importance of the use of ambiguity in the description of what has happened to a character, what she is doing, or what she is thinking. Sometimes, if one paints too clear picture of these events, we are forced to develop a specific view of the character: strong approval, or disapproval. What the author may want is a feeling of ambiguity about the character: I like her, but . . . So, for example, in my latest novel, one of the main characters may have become pregnant by her brother. The circumstances and the symptoms are not clear. What did she (and he) do?

July 18, 2014

Punctuation: the comma

There was an article by Harry Mount in The Daily Telegraph recently. It was titled: “Commas and colons: without them we’re sunk.”

Harry Mount (born 1971) is an English author and journalist, since 2009 a frequent contributor to the Daily Mail. He has written several non-fiction books; topics include his time working in a barrister’s office, British architecture, the Latin language, and the English character and landscape.

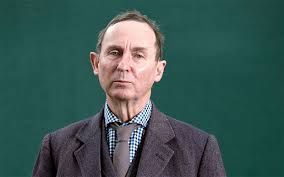

I don’t know Harry Mount, but he looks like a presentable, intelligent chap. In any case, what he said about punctuation makes sense to me:

“There’s one aspect of grammar that’s wonderfully simple and easy to learn. . . . Putting aside a few really obscure punctuation marks, the 15 main elements are: the full stop; colon; semicolon, comma, apostrophe, quote marks; question mark, exclamation mark; round brackets; square brackets; hyphen; dash; asterisk; ellipsis and slash. Most of these are pretty easy. Even people with dodgy grammar can use practically all of them pretty well. . . . It’s mainly the comma and the apostrophe that let people down. The apostrophe gets wickedly abused and not just by grocers. The comma is underused, particularly in its agile capacity as a throat-clearer, a pause-provider and direction market in a sentence. Just look at Churchill’s famous speech – and one of his longest sentences – without the merciful assistance of the comma (and the odd semicolon):

We shall fight on the beaches we shall fight on the landing grounds we shall fight in the fields and in the streets we shall fight in the hills we shall never surrender and even if which I do not for a moment believe this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving then our empire beyond the seas armed and guarded by the British fleet would carry on the struggle until in God’s good time the New World with all its power and might steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.

“Without the commas, Churchillian prose loses all its careful pacing - and you’re lost, too.

“Punctuation, more than anything else, turns the written word into the spoken word inside your head. Know your punctuation, and you can magically signal to the reader of your writing when to speed up; when to slow down; when to make the prose flow; when to give it a stop-start, staccato rhythm; when to pause; when to trail off into ellipsis . . .

“Without precise punctuation, who could tell the difference in meaning between these two sentences? (a) “My favourite things in the world are Abba, tartar sauce, and fish and chips on the last fairway.” (b) My favourite things in the world are Abba, tartar sauce and fish, and chips on the last fairway.” It’s the Oxford comma there that distinguishes between the keen gourmet and the keen golfer.

“At first hearing, an expression such as “the non-restrictive comma” will freeze all but the biggest brains. But explain the difference between “Sailors, who are drunks, are dangerous” and “Sailors who are drunks are dangerous”, and most children will get it in a second. Insert the non-restrictive commas and you’re being rude to all sailors; take them away and you’re being rude only to the restricted group of sailors who are drunk.”

July 11, 2014

Summer Reading

There was an interesting article in The Daily Telegraph on July 8th which was subtitled: “‘I couldn’t put it down . . . Holidays are not the time and place to read books that you think you ought to read’, says A N Wilson. So, yes, leave Thomas Piketty at home.”

Wikipedia informs me that “Andrew Norman Wilson (born 27 October 1950) is an English writer and newspaper columnist, known for his critical biographies, novels, works of popular history and religious views. He is an occasional columnist for the Daily Mail and former columnist for the London Evening Standard, and has been an occasional contributor to the Times Literary Supplement, New Statesman, The Spectator and The Observer.”

Mr Wilson says that “there is a revealing and amusing survey that has been conducted by a maths professor for the Wall Street Journal. It is based on the ‘popular highlights’ chosen by users of the Amazon Kindle and comes up with a list of the summer’s ‘most un-read books’. In the past when we only read books in book form, it was impossible to know, scientifically, how far the average reader had penetrated into , say, Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time – an impenetrable work, which it is sometimes tempting to believe that no one, except, perhaps, the book’s original copy-editor, has ever read to the end. But now that so many of us read books on Kindle, it is possible to make an educated guess about how far the average reader has got.

“Each best-selling book’s Kindle page lists the five passages most highlighted by readers. These extracts, designed to whet the appetite of other Kindle users, would – if they represented a thorough reading of the works considered – surely contain quotations from the whole book, and not just from the first few pages. Jordan Ellerberg has come up with a playful ‘Hawking Index’ with which to estimate how much of a book most people have read. The top five ‘highlights’ from Donna Tartt’s novel The Goldfinch, for example, all come from the final 20 pages of the book, which suggests that 98.5 percent of readers made it to the end. Highlights from Michael Lewis’ page-turning analysis of financial sharp practice, Flash Boys, suggest most people only read the first 21.7 percent of the book.

“And how about the book we of the Chattering Classes are all supposed to be reading and talking about this year – the French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century? Here the quotes do not dig deeper into his 700 pages than a pathetic 2.4 percent – in other words, Piketty, the great economic sage of our time, is as unread as Hawking, our greatest scientific sage.

Wilson goes on to observe that, for most of us, a holiday is a time of relaxation with the distractions of children, sightseeing, family and friends. He says, “Many is the thick paperback edition of some supposedly ‘great book’ that either gets left behind in the rented villa or hotel, or comes back home with only its first 30 pages smudged with sun-tan lotion. The idea that this should induce ‘guilt’ is absurd. Although to be as well-read as possible is a sort of duty of any intelligent person, this does not mean that it is a duty to read Plato’s Republic on a beach, or Proust by the poolside.”

Wilson says that the best sort of holiday reading is short. In this case, he would probably recommend taking Hemingway’s short stories along, and I would agree. In my view, the best summer reading is something that keeps inviting us back, all the while keeping us interested.

Of my own works, I would recommend Sin and Contrition (there’s a different sin in every chapter, and a discussion with the sinners at the end). Or Efraim’s Eye or The Iranian Scorpion (both are unique thrillers).

July 3, 2014

Review: The Guns at Last Light

I bought this book on the recommendation of a friend who fought (and won a Silver Star) in the Second World War. It was well worth reading, although the text runs to 641 pages (plus 234 pages of Notes, Sources, Acknowledgements and Index). There are 16 pages of photographs, as well.

This is volume three of the Liberation Trilogy written by Rick Atkinson, and it covers the war in Western Europe, 1944-1945, beginning with the invasion of Normandy. It won the Pulitzer Prize. The other two volumes of the Liberation Trilogy are: An Army at Dawn (covering the war in North Africa, 1942-1943) and Day of Battle (covering the war in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944).

For me, the most remarkable aspect of The Guns at Last Light is the enormous depth of research that went into it. In fact, Atkinson says in his Acknowledgements that it took him fourteen years to write the Trilogy. Every battle is described so that one feels like a well-informed observer, and there are maps aplenty to which to refer. One is left with a clear understanding of what the objective of the battle was, what went right and what went wrong, and, and what difference in made, ultimately. The story is largely told from the viewpoint of the relevant commanding officer, but with commentary provided by junior officers and even enlisted men.

The focus is strategic, rather than tactical, and Atkinson reinforces this emphasis with portraits of the officers in command. These portraits are formed from the comments of colleagues, superiors, subordinates, others and the individual himself. For example, Eisenhower comes across to me as a man who had an extraordinary ability to motivate, cajole, an occasionally order wayward senior officers to pull together in the same direction. Montgomery comes across as an egotistical prima donna, who over-rated his own skills as a general. These portraits come alive through timely, pithy remarks that Atkinson has found and included.

There are statistics on everything from the quantities of ammunition expended to the number and sizes of boots used by the GI’s, but they are inserted at appropriate moments. Moreover, the battles behind the lines are covered, as well: particularly logistics; but also care for the wounded, injured and dead; and ‘recreation’.

Perhaps the one thing which is missing is the perspective of the individual soldier in combat, though there are many brief comments on what it was like. To be fair, I think it is impossible to tell so sweeping a story from the perspective of both the commander and the individual soldier. What does come across clearly it the enormous physical, mental and spiritual hardships that the soldiers endured.

The story is not told entirely from the allied point of view. There are passages which cover German activities, from Hitler on down.

For as long as it is, this is not an easy book to put down. The writing is fresh and innovative. There is a sense of immediacy. One knows in general, how things will turn out, but once a particular battle has begun, one wants to find out exactly what happened and why. When one does put it aside, it is easy (and rewarding) to pick it up again.

Because of my own interest in Italy, I’m planning to ready the second of the Trilogy books.

If you’re interested in military history, they don’t come any better than this.

June 19, 2014

Penny Vincenzi

There was a full page article on the June 16 issue of The Daily Telegraph about Penny Vincenzi. It was written by Byrony Gordon, who covers women’s issues for the Telegraph. She says that “Penny Vincenzi’s books are an epic saga containing family secrets, romance and seriously strong women. ” I’ve read one of Vincenzi’s novels (there are 17) and I would agree with this characterization.

One particular quote in the article caught my eye. After saying that it takes her about a year to write a book and she never plots anything out, Gordon quotes Vincenzi, “I haven’t the faintest idea what is going to happen, ever. I just get the kernel of the idea, which in this case was supposing a company was about to go under, and then the characters wander in. I never have any idea what is going to happen at the end. I truly don’t, which is why they are so long.”

Does she ever get writer’s block?

“Oh no,” she says with a shake of her head. “I have a friend who does books, too, and he was party to a rather intense conversation about writing. Someone asked, ‘What do you do when you get writer’s block?’ and he said, ‘I’m not clever enough to get writer’s block!’ I do think there’s an element of: ‘Oh, it’s my art, you can’t cut that bit out because that’s the core’ . I don’t agonise. I do have terrible days when I realise I have gone down a completely blind alley and I’ve got to come back. The only cure is to press the delete button, I’m afraid. I once deleted 20,000 words and I felt much better after that.”

One has to admire this about Vincenzi: she has an extraordinary talent to write in what sounds like a stream-of-consciousness mode while at the same time having a keen awareness of what her readers like. She is a successful writer and it works for her.

What caught my eye about this article was the contrast with my style. I, too, take about a year to write a book, but I do a lot of charity work and my books are shorter than hers. I write about 8 pages a week; she writes at least twice as much. Part of the difference is that I do agonise, and I do a lot of editing in multiple stages. For me, a novel has to be credible, and since I write ‘modern. real-world novels’, I spend plenty of time on research. For example, I’m currently writing a novel which is partly set in north west Africa, and I want it to be accurate. I also do quite a bit of planning: novel outline, chapter outlines, character portraits, and with my more recent novels: what’s the point of this novel? what’s its message? what would I like the reader to take away? This message is, for me, the central nervous system of the novel. The characters, the events all have to support this core sense. If there is no core sense, the novel is just entertainment, but, of course, it can be delicious entertainment.

As to writer’s block, I would call it a barrier, rather than a blockage. There are times, particularly in starting a new situation, when I’m unsure how to proceed. I’ve learned that what’s necessary for me is to sit here and think about it. An idea will present itself. I’ll reject it. Not good enough. How about this? I takes patience and perseverance, and sometimes – I agree with Vincenzi – it means starting over.

So, in a way, I envy the free-flowing style of Vincenzi, particularly when I’m trying to write something that engages our ideas, our emotions, our senses and our instincts all at once. But the free-flowing style would not be me.

June 6, 2014

Literary Criticism

Many (most?) authors think about literary criticism. We tend, after all, to be surrounded with it. Some we like. Some we don’t like, particularly criticism which we feel is unfair, or doesn’t understand what we are trying to achieve. Ultimately, the challenge that criticism (fair or unfair, understanding or oblivious) offers those of us who write is to try to see the criticism from the critic’s point of view, and to take away at least something of value.

I think it’s interesting to compare criticism with creativity. In a sense, they are opposite sides of the same coin. Both activities involve the creative impulse. The creative person (or author) produces something, and the critic evaluates it. They are interdependent activities it the sense that creating without evaluation may produce rubbish, while the critic depends on the author to produce something. As to which comes first (the chicken or the egg), I think that the creative impulse produces something and its existence calls the critic into being. Both the critic and the author speak the language of creativity, but their philosophies in the use of the language are quite different. The author uses the language to produce something which s/he sees as having value, while the critic’s urge is to find or evaluate that value. I think it is fair to say that that both the author and the critic could benefit from having some of the skills of the other. Certainly, authors could profit from having some of the critic’s ability to think about what is valuable. And critics would be more effective if they had more understanding of and familiarity with the creative process.

What makes all of this quite interesting is that there are no objective standards for what ‘good’ is for a writer or a critic. There are no tests to pass or qualifications to earn to be considered a ‘good writer’ or a ‘good critic’. ‘Good literary critics’ tend to be ‘prominent’ or ‘recognised’ - whatever that means – and ‘good writers’ are viewed similarly.

One of the difficulties which authors have with literary criticism is: on what basis is my work being judged? Is that a meaningful basis for my particular work? Critics seem to emphasise particular criteria as they evaluate a work. For example:

Is the plot interesting and credible?

Are the characters truly human (or not)?

Is the setting believable or realistic?

What about the author’s use of language?

What about spelling, grammar and syntax? (I read recently that a novel without any punctuation was awarded a major prize in the UK. Imagine what a nightmare that would be for the reader.)

What is the intended audience for this work?

Will this piece of work make money? (Critics associated with main stream publishers put much emphasis on this.)

If we look at this piece of work from a philosophical, religious, ethical, sociological point of view, what do we find?

What ‘school of literature’ (if any) does this writer represent?

There are also various ‘schools’ of criticism, such as:

Reader Response Criticism: how and why will the reader (what sort of reader?) see this novel?

New or Formal Criticism which treats the work as a stand-alone entity, without reference to the author, the reader or historical context

Feminine Criticism: it’s all about gender or lack of gender: the text reflects a particular view of men or women?

Marxist Criticism: focuses on economic issue, capitalism and the plight of the poor

Historical Criticism: analyses the work from the perspective of history

Psychoanalytic Criticism: views the work through the lens of psychology

Authorial Criticism: to know the work one must know the author

So . . . Might it not be better of the author and the critic could actually discuss a critical point of view before it is published, not with the purpose of ‘watering down’ or changing the criticism, but with gaining a clearer perspective of each other’s understanding and intentions?

May 29, 2014

US Book Ban

The following article from today’s issue of The Daily Telegraph caught my eye:

Michael Grove will regret the decision to divide literature into “nationalistic categories” on the GCSE syllabus, a Nobel Prize-winning author has said. Toni Morrison, an American, attacked the Education Secretary’s reported plans to drop classic US novels and plays from the school curriculum in favour of British works. She also joked that the decision was “payback” for US universities replacing English literature with American literature in their syllabuses.

Mr Grove has been criticised after reports that he wanted To Kill a Mocking Bird by Harper Lee, John Srteinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and The Crucible by Arthur Miller to be removed from the curriculum. More than 30,000 people have signed an online petition calling for them to stay.

Morrison, made a Nobel laureate in 1993, was asked about Mr Grove’s reforms when she appeared at the Hay Festival. “I tell you [they] will regret it,” she said. “When I started in grad school in the fifties at Cornell University, that was the first time there was such a thing as American literature. It was always English literature. American, what was that? So now it’s just payback. Just because we got rid of English literature and moved to American, you’re going to fix it.”

Paul Dodd, of the OCR exam board, said at the weekend that it had left American texts off its English GCSE syllabus because of government guidelines. “The essential thing is that in the new GCSE English literature you cannot do fiction or drama from 1914 unless it is British,” he said.

Mr Gove denied the claim, saying: “I have not banned anything. Nor has anyone else. All we are doing is asking exam boards to broaden – not narrow – the books young people can study for GCSE.” But the OCR last night confirmed that it had dropped many American texts form GCSE English so pupils could study more novels and poems by British writers. The new syllabus will see pupils study Shakespeare along with novels by George Orwell, Meera Syal, Charles Dickens and HG Wells.

My reaction to this – as an American – is that it’s all a tempest in a tea pot, and I doubt very much that there is any sort of “payback” involved. Who cares about the nationality of an author? Is there a distinctive ‘American Writing Style’? While the characters and the settings of American novels will tend to be different than their British counterparts, does this make the appreciation of the work, as literature, in the mind of a fifteen-year-old different? I think what a fifteen-year-old will notice is the unfamiliar settings and maybe the strange characters, but will s/he think, “this is a different kind of literature”? I doubt it. In fact, if what we want to do with fifteen-year-old students is to confirm in them a joy of reading, isn’t it sensible to suggest works that will seem more comfortable and familiar – rather than foreign – to them?

May 21, 2014

Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut, in his book, Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction, listed eight rules for writing a short story. While I would probably adopt a different set of eight rules, I think Vonnegut’s rules are quite interesting:

1. Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

For me, the important parts of this rule are: “total stranger” and “time wasted”. One never knows who will decide to read a book that one has written, and it’s important that whoever decides to read it feels that it is time well spent. This suggests that the onknown reader got something out of the story: enjoyment, new knowledge, new ideas . . .

2. Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

This is essential!

3. Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

A character with no desires is not human and therefore not very attractive or interesting.

4. Start as close to the end as possible.

For a short story, this certainly makes sense. I’m not sure this holds true for a novel. One example that springs to mind is Emily Bronté’s Wuthering Heights in which the characters are young children at the beginning. The Russian novelist, Tolstoy, didn’t believe in this, nor did Sholokov. However, the rule, it seems to me, is useful in that it encourages one not to included unnecessary material.

5. Every sentence must do one of two things-reveal character or advance the action.

It depends, I think, on what one means by “advance the action”. A short story, by its very nature has to be tightly told. In a novel, there is more latitude for scene- and context-setting. I would argue that setting the scene and establishing the context are important in advancing the action, so long as they hold the reader’s interest.

6. Be a Sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them-in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

I’m not sure one has to be a Sadist, but it certainly shows the reader what a character is made of when tragedy strikes. I good example is the principal character Henry in Sable Shadow and The Presence.

7. Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

I sense a slight conflict between this rule and rule number 1. The one person for whom we write is a total stranger? For me, the second sentence in this rule makes sense: one has to have focus in one’s writing, otherwise, it pleases no one.

8. Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

I think this applies to a short story more than to a novel, but I’m not sure that Hemingway would have agreed with this. His short stories often have surprising endings.

April 29, 2014

Love

Love is a very complex human emotion. It comes in many forms. Here are some examples from my novels:

From Fishing in Foreign Seas: (Jamie and Caterina are on a sightseeing excursion to Erice, Sicily. This is the kind of love that young people dream of; where two people fit together perfectly.)

He looked into a narrow gorge which was covered on the near side with vines and seemed to stretch down into infinity. “Yes, I see what you mean. I can’t even make out what’s at the bottom.”

she pleaded. She took a step backward and held out her hands to him.

He crossed over to her. “The railing is quite strong. You wouldn’t fall over,” he assured her.

She looked at him, her lips compressed: “I am afraid of heights. When I get near a place like this, I am afraid I throw myself over.”

“But you’re not going to do that!”

“I know, but I still get the feeling. . . . As if some demon inside of me will take control . . . and throw me over.”

“But you don’t have any demons inside,” he protested.

“I know of one,” she confessed. Her eyes were misty: “. . . it is called ‘self-doubt’.”

He stared at her in utter amazement, then he felt her vulnerability, and he drew her close to him. “Let’s get a bite to eat,” he suggested.

They sat at a table in an almost-deserted patisserie. She would look at him for a moment and then she would look around her. The corners of her mouth were turned down and her head was inclined to one side.

“Caterina . . .” She looked at him, her face full of disappointment in herself. He took her hands: “I love you!”

She took a deep breath, not believing what she heard. Then the dam burst inside her. “Oh, Jamie, I love you so much! I never believed I could love anyone like this!” Her face was streaming with tears.

“You beautiful, wild, wonderful girl!” He got up and hugged her. “. . . Do you suppose they have any champagne here?”

She wiped her eyes with a napkin. “I doubt it, but they probably have some prosecco – which might be good.”

Jamie got up, ordered a bottle of prosecco and pointed out some assorted sweets to the waitress. She came to their table carrying an unopened bottle and the tray of sweets; then she showed them the bottle.

Caterina frowned. “Haven’t you got anything better than that?”

“Yes, Miss, we have champagne.”

“What champagne is it?”

“We have one bottle of Moet in the refrigerator.”

“Excellent! We’d like that, please!”

They sat gazing at each other while the waitress went for the champagne. “Jamie, are you sure you love me?”

“Yes, I love you because you’re clever, you have a sense of humor, you’re a little wild, because you’re the part of me that’s missing, you’re beautiful, and because you’re a bit lonely!”

Wordlessly, she got up from the table, knelt down and hugged him.

From Sin & Contrition: (Where Josie is swept off here feet by Dr. Bill Thompson, and while they love each other, there’s a major obstacle.)

Josie and Dr. Thompson were lying naked in her bed that Sunday evening. He was nuzzling her breasts.

“Bill, have you ever been married?”

He looked up at her suddenly: “Why do you ask, my love?”

“Because I want to know.”

Dr. Thompson rolled over onto his back. “I was married once – it didn’t work out too well.”

“When was that?”

“About eight years ago.”

“Did you get a divorce?”

“She doesn’t want to give me one.”

“It’s possible to get one in Pennsylvania, even if one person objects.”

“I know, but I haven’t had any reason to – until now.”

“What do you mean?”

“I love you, Josie.”

It was the first time he had said it, and she felt elation. “I love you, Bill. . . . Would you get a divorce for me?”

“It’s complicated, Josie. There are kids involved.”

“There are kids?”

“Yeah, four kids.”

Josie began to feel a knot in her stomach. “How old are they?”

“Seven, five, four and two.”

“And you’re still living with your wife and the children?”

“Well, yeah, but it’s not what you’re thinking. I’m just staying for the children.”

“Do you and your wife still have sex?”

“No. . . . Now, Josie, you’ve just got to be patient with me. We’ll work something out.”

Josie slept very little that night. She kept turning over in her mind her questions: could they work something out? That would be absolutely heaven! Could she convince him to spend more time with her? If he got a divorce, could she handle four kids – even part time? She thought so.

Finally, and reluctantly, she decided to do a little investigating.

From Efraim’s Eye: (Paul confesses his affection for Naomi, knowing perhaps that their relationship is not meant to be.)

The wind rattled the green canvas awning that covered the roof restaurant. They were sitting side-by-side so that they could look out to sea. A waiter had cleared away their breakfast plates of fruit and pastries. Naomi was sipping her coffee pensively. She turned slightly to face him. “Do you love me, Paul?”

Unprepared as he was for that question, Paul knew that there could be only one answer. “Yes, yes, of course I love you.”

Naomi’s head tilted, and her gaze fell to the table cloth. Uncertainly, she asked, “Why do you love me?”

Instinctively, Paul knew that his answer must not include the word ‘beautiful’ or one of its synonyms. He said, “You’re a very sweet idealist, Naomi. You are a woman with great talents as a linguist, as a musician, and in dealing with people. But for me, best of all, is your joie de vie. Life is a great, pleasing adventure for you, and it’s delightful to be with you.”

For some moments, Naomi gazed at him, apparently repeating his words in her mind. She asked, “So you think I’m a sweet, talented, adventurous woman?” She pronounced the word ‘woman’ awkwardly, as if it were a term unfamiliar to her.

He smiled. “For a four word summary, that will do.”

Paul knew the answer to the reciprocal question. She loved him as a daughter loves, and he had awakened her latent brilliance as a lover. But, for her part, she had wanted to know whether she, herself, was a person who could be loved.

She took his hand in hers, and they sat, quietly gazing out to sea, each lost for some time in his or her own sunny thoughts.

From The Iranian Scorpion: (Robert invites Kate to come to Dubai with him; they are lovers, but actually they are friends.)

“Kate, James has proposed that I come to Dubai for a couple of weeks R & R. Would you like to come along?”

“But what would I do in Dubai?”

“Well, you could lie on the beach, or by the pool, in your bikini.”

“I don’t have a bikini.”

“Well, you can wear your designer one-piece, then.”

“What else is there?”

“Well, we would be staying at the five-star Jumeirah Hotel.”

“I am sick of hotels.”

“We could stay in one of their tropical garden residences.”

“What else?”

“We could go shopping in the Mall of the Emirates.”

“I hate shopping malls.”

“Well, there are some nice little shops in the hotel.”

”What else is there?”

“Well, I see that Beyoncé is playing at one of the clubs.”

“I don’t like Beyoncé.”

“How about Randy Travis?”

“What else?”

“I see that the Amala restaurant has fresh oysters.”

Kate made a face.

“They also have fresh Maine lobster.”

“What else, Rob?”

“Well, there are a couple of new positions we could try.”

She looked away.

“Are you not coming then, Kate?” When he moved to look at her face, he saw that she was giggling.

“Of course I’m coming!”

And this from Sable Shadow and The Presence: (Henry reflects on his relationship with Suzannne.)

After that, we just couldn’t get enough of each other. We didn’t move in together, but we might as well have. I kept some of my business clothes at Suzanne’s place, and she kept some of hers at my apartment. That way, we could always have dinner together, make love, sleep and have breakfast together. My world revolved around Suzanne, and hers around me. Anybody else was superfluous. While we were at work, we spoke to each other two or three times a day.

I was really in love for the first time in my life: I would have done absolutely anything for Suzanne. The miracle of it was that she felt the same about me. It didn’t seem possible that anyone could love me so much. This one, magical woman had wiped away all my self-doubts and my Angst.

April 19, 2014

More reviews: Sable Shadow and The Presence

Two people from Reader’s Favourite have submitted the following reviews:

Kathryn Bennett: “Sable Shadow & The Presence by William Peace is the fictional autobiography of bright introvert Henry Lawson. He hears strange voices at a young age, voices that he does not recognize and believes one to be the Sable Shadow, who is a confidant of the devil, and the other is The Presence who may be a worker of God. For him life becomes a struggle in a chess game of sorts and these voices follow him

from childhood through life until he attempts to kill himself, and must then begin to rebuild himself, making a new identity and essentially a new person.

Some books touch you deeply and some make you think, and some manage to do both

within the pages of one book. For me Sable Shadow & The Presence by William

Peace did both. It made me think and it touched me. The thoughts that this book

manages to provoke about good and evil will certainly make you delve into some

interesting discussions with friends and loved ones. Each page for me was like

peeling back another layer of the onion to enjoy and read. I picked it up and

was not able to set it down until I was finished, and even then I felt like I

could read more. What would you do if you had the presence of good and the

presence of evil speaking to you for your entire life? While Henry has his

issues, I personally may not have come out as well as he did and I am not sure

I would be able to rebuild myself even with support after such a hard fall.

William Peace gets a thumbs up from this author on an inventive story line that

evokes thoughts and emotions – a recommended read. 5 stars”

Ray Simmons: Sable Shadow & The Presence is a thoughtful and illuminating work of fiction by William Peace. The main character is Henry, an observant man, a natural philosopher who goes through life looking for meaning and trying to figure out what lies behind appearances. He also goes through life listening to two opposing voices that

may represent good and evil. The voices are subtle and indeed, for a period

when he is younger, he’s not sure if they aren’t from inside himself, but over

time he becomes convinced that they are external. We follow Henry as he goes

through the major events of his life. During early childhood he confides in his

sister Jenny about the voices and it is she who names the sinister voice Sable

Shadow. In many ways Henry has a typical American life, if there is such a

thing. He takes us through childhood, the teenage years, first love, first

tragedy, the college years, and a stint in the Navy. We watch him fall in love

and navigate his way through the adult years.

William Peace has created an enduring and thought provoking work in Sable

Shadow & The Presence. The novel avoids the exaggerated melodrama found in

so many current novels. The writing is clean, crisp, and directly to the point.

The characters and situations reflect a modern American life and the musings of

Henry mirror questions all educated, thoughtful people have asked at some point

in their lives. I give it five stars. There should be more novels of this

nature out there. 5 stars”