William Peace's Blog, page 50

August 24, 2015

Social Media Backlash

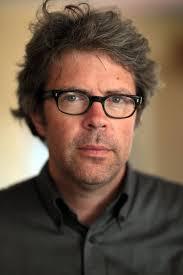

There was an article entitled “Authors Stifled by Fear of Social Media Backlash, Franzen Warns” which appeared in the 22 August edition of The Daily Telegraph. Jonathan Franzen is an award-winning novel and author of Freedom and The Corrections.

Jonathan Franzen

Franzen claims it is becoming more difficult for writers to produce great novels in the era of social media because they are too frightened of a public backlash to be truthful. He says that the “firewalls” protecting authors from their readers have now disappeared, and there is now too much pressure to use social media to promote new works.

The article says that he has famously refused to go on Twitter, having labelled it “unspeakably irritating”. Now he has spoken of his concern it its impact on novelists, telling The Guardian: “The ways in which self-censorship operates – the fear of being called a bad name – people become very careful. And it becomes very hard to be creative, actually. Because you’re worried about what you might be called, and whether its true or not. There used to be rather serious firewalls between the artist and the buying public – the gallery, the publisher. And technology demolishes that wall and basically says: self-promote or die. And that is a bad head for any sort of artist to be forced into.”

Yesterday he was derided on Twitter after revealing he had once considered adopting an Iraqi orphan, adding: “One of the things that had put me in mind of adoption was a sense of alienation from the younger generation. They seemed politically not the way they should be as young people.”

I’m afraid I don’t agree with much of what Franzen says. I congratulate him for wanting to adopt and Iraqi orphan; let’s hope it wasn’t critics who dissuaded him! I grew up in an era where we used to say to bullies, “Sticks and stones will break my bones, but names will never hurt me!”

I believe that if an author takes a well-reasoned position on a subject which may be controversial, and he is derided by trolls, there will be plenty of people who agree with the author but don’t bother to say so. This is what good authors have done for centuries, and this is no time, in an age of social media and terrorism, for authors to lose their courage to speak freely!

Franzen might well say to me, “Well, but you have never been attacked by trolls.” True. But I’m certainly not going to change my position if they do. Besides, I live in a country where personal threats are illegal. There are some things which my characters have said in my novels which may very well offend some sensitive people. They’ll just have to get over it.

As to social media, I have this blog and several Facebook accounts. I’m on Goodreads and Amazon. I’m not on Twitter – mainly for the reason that I don’t have time to prepare daily tweets. The world is changing: get on board!

Franzen bemoans the loss of “firewalls”. I don’t think that firewalls are helpful to the author in the long run. Any artist should have access to the public’s reactions to his/her work – good or bad. Dickens had very few “firewalls” between himself and the public. Why should we?

August 14, 2015

The Art of Emotional Composition

Nancy Quatrano has an article in the August 2015 issue of The Florida Writer which caught my eye: “Show vs. Tell: The Art of Emotional Composition”. I thought that many of the points she made in the article were good. I just objected to the didactic tone of the article, so I’ll summarise and comment on the points she made.

Nancy Quatrano

Ms Quatrano makes the point that there are three way for an author to transfer information to the reader: exposition, dialogue and narrative. Exposition is an invasion by the author into the story; it is characterised by the use of the word ‘had’. An example would be; “Ann had told John that she was getting a divorce.” Expositions are shortcuts, or flashbacks, and involve the use of the passive voice. Ms Quatrano recommends the use of exposition “lightly and carefully sprinkled in, like expensive seasoning.” I think that exposition should be avoided altogether on the basis that it deprives the reader of experiencing what is going on in real time.

She recommends checking for the use of -ly words (adverbs), and suggests that this is a hint that the wrong verb has been used. I agree that the right verb, used alone, makes better reading than a weak verb and supporting adverb in the sense that it better expresses the author’s intent. In my experience, though, it isn’t always possible to convey how the action feels, without an adverb – even with the help of a thesaurus.

Use of the explaining words and phrases: “because” or “in order to” should be avoided, Ms Quatrano suggests, because it is just another form of telling, rather than showing the reader. It is OK to use them in dialogue. Agreed.

She says: “Stay away from relative terms like big, small, fast, slow, pretty, ugly. Show the reader what they need to see through dialogue and scenes. Concentrate on showing actions and reactions, not on explaining what’s going on.” I would say: stay away from relative adjectives for a different reason: they are vague. Readers find vagueness boring. In my experience, sometimes the use of an unconventional noun or adjective conveys exactly the picture I’m trying to paint. How about: instead of saying ‘little girl’, we write ‘knee-high Goldilocks’?

She says: Avoid the emotion killers: am, is, are, was, were, be, been and being. These slow down the emotional intensity. This is true, but she doesn’t say why. These are all forms of the verb ‘to be’, which is an intransitive verb, that is: a verb which does not need a direct object to complete its meaning. Intransitive verbs do not convey action. Readers like action, and emotion arises from action, not from ‘being’.

Coming back to Ms Quatrano’s other two choices: dialogue and narrative, I tend to use narrative sparingly and mostly to set the scene or to transition from one scene to the next. I use dialogue to define characters, to tell the story and to suggest key messages to the reader.

August 6, 2015

The Creative Benefits of Keeping a Diary

There is an article by Maria Popova on her BrainPickings.org site about the creative benefits to writers of keeping a diary. Since I have not kept a diary except briefly in my early teens, and that has long since disappeared, I was curious about the benefits. Maria Popova is a Bulgarian writer, blogger, and critic living in Brooklyn, New York. Her Brain Pickings blog features her writing on culture, books, and eclectic subjects.

Maria Popova

Ms Popova says: Journaling, I believe, is a practice that teaches us better than any other the elusive art of solitude — how to be present with our own selves, bear witness to our experience, and fully inhabit our inner lives. She goes on to quote famous writers who have kept journals to discover their perceived benefits.

Anais Nim, from a lecture at Dartmouth college: Of these the most important (benefits) is naturalness and spontaneity. These elements sprung, I observed, from my freedom of selection: in the Diary I only wrote of what interested me genuinely, what I felt most strongly at the moment, and I found this fervour, this enthusiasm produced a vividness which often withered in the formal work.

Virginia Wolff says: Still if (my diary) were not written rather faster than the fastest type-writing, if I stopped and took thought, it would never be written at all; and the advantage of the method is that it sweeps up accidentally several stray matters which I should exclude if I hesitated, but which are the diamonds of the dust heap.

André Gide’s view: A diary is useful during conscious, intentional, and painful spiritual evolutions. Then you want to know where you stand… An intimate diary is interesting especially when it records the awakening of ideas; or the awakening of the senses at puberty; or else when you feel yourself to be dying.

Susan Sontag says: Of course, a writer’s journal must not be judged by the standards of a diary. The notebooks of a writer have a very special function: in them he builds up, piece by piece, the identity of a writer to himself. Typically, writers’ notebooks are crammed with statements about the will: the will to write, the will to love, the will to renounce love, the will to go on living. The journal is where a writer is heroic to himself. In it he exists solely as a perceiving, suffering, struggling being.

Eugéne Delacroix muses: Even one task fulfilled at regular intervals in a man’s life can bring order into his life as a whole; everything else hinges upon it. By keeping a record of my experiences I live my life twice over. The past returns to me. The future is always with me.

Virginia Wolff again: How far, we must ask ourselves, is a book influenced by its writer’s life — how far is it safe to let the man interpret the writer? How far shall we resist or give way to the sympathies and antipathies that the man himself rouses in us — so sensitive are words, so receptive of the character of the author? These are questions that press upon us when we read lives and letters, and we must answer them for ourselves, for nothing can be more fatal than to be guided by the preferences of others in a matter so personal.

And, in conclusion, Ms Popova writes: This, perhaps, is the greatest gift of the diary — its capacity to stand as a living monument to our own fluidity, a reminder that our present selves are chronically unreliable predictors of our future values and that we change unrecognizably over the course of our lives.

I must say that I’m un-persuaded. I don’t feel the need for a ‘living monument’ to my fluidity of self. I seem to have enough difficulty managing the fluidity of my feelings, my values, my priorities, my relationships, my identity from moment to moment and from day to day! But it does seem to me that the idea of capturing a ‘diamond in the dust’ is a good one; perhaps I should establish just such a file! One activity that I find myself engaged in more and more as I grow older and I observe what are actually ordinary things and events is to ask Why? The answers are quite astonishing sometimes, ranging from the whimsical to the unlikely to the enlightening. Also, I’m beginning to make a habit, when I observe an unusual facial expression or event, of asking, How would you describe that? It’s an exercise in creativity, of avoiding ordinary language.

August 3, 2015

Review: Go Set a Watchman

I was one of the 100,000+ readers who bought a copy of Go Set a Watchman on its first day of issue. For me To Kill a Mockingbird is a great work of literary, social and political significance. So, I was anxious to read Harper Lee’s second (or first) novel which apparently served as the draft which became To Kill a Mockingbird. The pre-publication reviews of Watchman, which were largely uncomplimentary, didn’t deter me.

Harper Lee

So, Lee submitted a draft of Watchman to publisher J B Lippencott, where an editor suggested that she re-write the book in the first person, from the perspective of Scout, a young girl. The re-writing took two years, during which Lee became so frustrated she threw the manuscript out the window of her New York apartment into the snow. Her literary agent persuaded her to retrieve it and carry on. Reportedly, during the re-writing, Lee’s editor was closely involved with her.

Two of the principal characters, Scout and her father Atticus, appear in both novels. But, in Watchman, Scout has become Jean Louise, a twenty-something, new York-based, adult, and Atticus is now in his seventies, still living in the rural Alabama town. Three new major characters are introduced in Watchman: Henry Clinton, a life-long friend and marriage prospect; Aunt Alexandra, her father’s sister, an arch, small-town, Southern traditionalist; and Dr John, her father’s brother, and eccentric but wise philosopher. Jem, Scout’s older brother, is strangely dead.

In Mockingbird, the plot focused on the trial of a black man who is wrongly accused of raping a white woman; he is defended by Atticus, the small town lawyer. This tightly-focused plot yields themes of justice, racial and sexual equality, love and duty.

In Watchman, the story follows Jean Louise’s relationships with Henry, her aunt, her uncle and her father. Race is again an issue, but less dramatic and compelling: the grandson of Jean Louise’s childhood black, nanny/mentor has killed an old white man in a car accident which was the grandson’s fault. This time, Atticus is revealed as a racist who wants to limit the freedom and political power which black people have acquired over the preceding twenty years. The message I get from the book is that how one acts on vital issues, such as race relations, is determined by our conscience (the Watchman), and our conscience is influenced by our context, which must also be respected. At the very least, Watchman seems to be a watering down of the clear, landmark message of Mockingbird. Disappointing!

The characters, the setting, and the context of Watchman are all well defined, credible and real. These descriptions rely on interesting, unique writing. Some of the dialogue comes across as contrived, rather than natural. Frequently, there are references to obscure literary figures: these references tend to confuse rather than illuminate. Apart from my concerns about the message of the novel, the plot seems to have been created ad lib. Too much text is devoted to setting the context, and exploring dead ends (Jean Louise’s relationship with Henry), and not enough effort is exerted on defining the role and implications of the Watchman.

One can’t help but wonder if the editor behind Mockingbird were still alive and involved with Watchman, what would the recent novel be?

July 26, 2015

Review: No Longer Human

I bought this book by Osamu Dazai at the Kaizosha Book Store at Narita Airport on the way back from Tokyo to London. It was one of perhaps a dozen novels available in English from the bookstore.

Having never read the work of a Japanese novelist, I was eager to try one.

The translator, Donald Keene, has an introduction in which he explains that the literal translation of the Japanese title, Ningen Shikaku, would be “Disqualified as a Human Being”. Having read the novel, I don’t feel that either title does the work justice, but I can’t think of a better one. Keene makes the point that Japanese writers and literary intellectuals, in general feel isolated (as is Yozo, the protagonist in No Longer Human) from the West, where the perception may be that Japanese writers have nothing interesting to offer.

Dazai (June 19, 1909 – June 13, 1948) grew up in a small town in the remote north of Japan. His family was wealthy and educated; Dazai himself was familiar with European literature, American cinema, modern painting and sculpture. So he was very much aware of Western culture. Dazai’s earlier novel, The Setting Sun, was reviewed by Richard Gilman in Jubilee: “Such is the power of art to transfigure what is objectively ignoble or depraved that The Setting Sun is actually deeply moving and even inspiring. . . . To know the nature of despair and to triumph over it in ways that are possible to oneself – imagination was Dasai’s only weapon – is surely a sort of grace.”

No Longer Human is told in the first person by Yozo the youngest child of a large, well-to-do family in the north of Japan. In this regard, Yozo’s background (and perhaps his feelings about others) mirror those of Dazai. The story begins in childhood and continues until about the age of thirty. Yozo is a good-looking child, but he suffers from and extreme lack of self-confidence, and to put my own diagnostic on it: he also suffers from some form of autism in the sense that he has difficulty interpreting the emotions and the motivations of others. His father, a powerful figure, remains remote. He feels disconnected from most of the humanity around him. His coping mechanism is to be the clown: valued by others as a sort of entertainer. While Yozo is obviously intelligent, his disconnection means that he has no real identity or a goal in life. Instead, he is buffeted hither and thither by the forces he encounters.

This theme of disconnection is central to No Longer Human, and it is reinforced by contrast with supporting characters. Yozo’s wife, Yoshiko, is trusting of other people to a fault. Yozo’s companion, Horiki, has an entirely selfish method of dealing with other people. Flatfish, Yozo’s family-imposed guardian, is entirely logical. Given that Japanese society is tightly constrained by a complex web of un-written rules of interaction, it must be particularly interesting in Japan to consider the fate of someone who has never learned the rules, but is Japanese.

Yozo stumbles from one disaster to another, but one cannot help but feel some sympathy for this crippled human being. These feelings of sympathy are aided by the various women who fall in love with Yozo for the “good boy, the angel” that he is. It deepens the tragedy that Yozo is unable to see past the feelings of self-denigration the kind, even loveable character that he is.

If No Longer Human is representative of modern Japanese literature, I would say: “Seek it out!”

July 15, 2015

The Secret of Great Writing

In the autumn of 1938, a sophomore at Radcliffe College, Francis Turnbull, sent her latest short story to family friend, F Scott Fitzgerald. His response is recorded in F Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters.

F Scott Fitzgerald

Dear Frances:

I’ve read the story carefully and, Frances, I’m afraid the price for doing professional work is a good deal higher than you are prepared to pay at present. You’ve got to sell your heart, your strongest reactions, not the little minor things that only touch you lightly, the little experiences that you might tell at dinner. This is especially true when you begin to write, when you have not yet developed the tricks of interesting people on paper, when you have none of the technique which it takes time to learn. When, in short, you have only your emotions to sell.

This is the experience of all writers. It was necessary for Dickens to put into Oliver Twist the child’s passionate resentment at being abused and starved that had haunted his whole childhood. Ernest Hemingway’s first stories ‘In Our Time’ went right down to the bottom of all that he had ever felt and known. In ‘This Side of Paradise’ I wrote about a love affair that was still bleeding as fresh as the skin wound on a haemophile.

The amateur, seeing how the professional having learned all that he’ll ever learn about writing can take a trivial thing such as the most superficial reactions of three uncharacterized girls and make it witty and charming — the amateur thinks he or she can do the same. But the amateur can only realize his ability to transfer his emotions to another person by some such desperate and radical expedient as tearing your first tragic love story out of your heart and putting it on pages for people to see.

That, anyhow, is the price of admission. Whether you are prepared to pay it or, whether it coincides or conflicts with your attitude on what is ‘nice’ is something for you to decide. But literature, even light literature, will accept nothing less from the neophyte. It is one of those professions that wants the ‘works.’ You wouldn’t be interested in a soldier who was only a little brave.

In the light of this, it doesn’t seem worth while to analyze why this story isn’t saleable but I am too fond of you to kid you along about it, as one tends to do at my age. If you ever decide to tell your stories, no one would be more interested than,

Your old friend,

F. Scott Fitzgerald

P.S. I might say that the writing is smooth and agreeable and some of the pages very apt and charming. You have talent — which is the equivalent of a soldier having the right physical qualifications for entering West Point.

F Scott Fitzgerald makes a very good point: that the most important skill of a writer (of fiction) is to be able to convey the feelings of his/her characters to the reader in a unique and compelling way. It is not enough to tell the story clearly and neatly, gaining the reader’s attention. As he puts it, we have little interest in a ‘soldier who is a only little brave’.

How does one convey feelings in this compelling way? First of all, as a writer, one must feel the feeling; it is not enough to imagine how it would feel. Then, one must place oneself into the character so that the expression of the feeling is consistent with the character’s personality: different people express anger (for example) in different ways. Finally, one has to ‘paint the picture’ carefully selecting from all the many available devices: How does the character look? What does she say? What does he feel? How do others react? What does it sound like? What’s a good analogy?

Easy to say. Not so easy to do!

July 10, 2015

The Character: David Dawson

General David Dawson is a character who appears in two of my novels: The Iranian Scorpion and Hidden Battlefields. He is the father of Robert Dawson, the principal character, a US Drug Enforcement Agent in both books.

Why is he there? Several reasons. He is a different character than Robert; he is impulsive, hot-tempered, impatient, and something of a womaniser; traits which Robert does not share with his father. But David is also brave (a decorated military commander), intelligent and ambitious; attributes which are visible in Robert, too. The general’s relationship with his son is complex. On the one hand, he is disappointed that Robert did not follow him into a military career. He wonders, sometimes, whether his son is worthy of his heritage. But at the same time, he feels genuine affection for his only son and admires his accomplishments as a DEA agent. There is also a love rivalry between the two men for a very attractive woman. This rivalry begins in The Iranian Scorpion and reaches crescendo pitch in Hidden Battlefields. In this situation, David’s wild impulsiveness, and Robert’s cool-headedness come into play.

Most readers will admire the general when he strays off his assignment as a nuclear weapons inspector in Iran, but one cannot be astonished when his impetuousness gets him into serious trouble. Similarly, in Hidden Battlefields, he places himself in situations where his military skills are called for, but are not always used to the best advantage.

Robert’s mother is mentioned in The Iranian Scorpion as an embittered ex-wife, but she re-appears in Hidden Battlefields as a happily re-married woman who successfully takes some control over her ex-husband in a situation where Robert has no levers to pull.

So for me, the secondary characters in a novel help to define the values and the personality of the main characters. Secondary characters also add depth and interest to a novel; without them, at best, a book becomes two dimensional. In addition, they are usually essential to the progress of the plot, and, as in both of the above novels, they help the author express a theme. The Iranian Scorpion, is about what it takes to succeed in a challenging situation: more than a intelligence, a plan and courage: it takes attention to detail and luck, as well. In the case of Hidden Battlefields the theme is that while we as individuals have major, un-resolved conflicts going on in our heads, we cannot reach our full potential as human beings.

July 3, 2015

Dealing with Pirates

The July issue of IBPA Independent magazine has an article entitled “My Battle with Pirates” by Rhonda Rees.

Rhonda Rees

The article begins:

Late one evening, shortly after I had self-published Profit and Profit with Public Relations: Insider Secrets to Make You a Success, I decided to run a Google search for it – and there it was, staring me right in the face. My book, along with hundreds of others, was being given away free with the simple click of a button. By the time I had discovered this, one website had already given away 600 copies of my book, and another one, which had the nerve to say that it had my blessing, had given away 1,500 copies. As you can imagine, I was shocked. And as I now know, you may find yourself in this very same unwanted position. Any book can be pirated online. It’s not just the famous writers and recording artists who are being ripped off. Even the fact that I trademarked and registered my title here in the United States didn’t keep my book safe, since many pirates are located overseas.

I decided to take her advice and run a Google search: “ free download”. Three of my six novels produced results of commercial websites that had my copyright material on them. Two of the three promise “free downloads”. All three referred me to the website http://www.donnaplay.com, where I had to register to be eligible for the free downloads. It turned out that I had to provide my credit card information, because after a five day free trial, there is a monthly fee. So the downloads aren’t really free.

The two websites that initially came up promising free downloads had contact forms where I could request that the page be deleted from their site. The third had a similar request form, but it was not live, and the telephone and email information was obviously false.

So what does Ms Rees recommend?

Run a Whois search to find information such as who owns the domain names, where and when they were registered, and when they expire.

Send out emails to find out what company is hosting the site so that a DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) notice can be sent out. The notice has to be correctly worded and DMCA.com can help with that task. There is also a free sample DMCA letter posted by Gene Quinn, a patent attorney and the founder of IPWatchdog.com (ipwatchdog.com/2009/07/06/sample-dmca...)

Send the DMCA takedown notice by email to the web hosting company which is obligated to notify its clients (the culprits) within 24 hours to have them remove all the information.

I, also, was rather shocked that half of my novels are being pirated. I think my next step will be to get my publisher involved with http://www.donnaplay.com. If that illegal site has three of my novels, they must have at least one hundred of the publishers other titles.

I’ll keep you posted!

June 24, 2015

Payments by the Page

In yesterday’s Daily Telegraph there was an article “Amazon to Pay Authors by How Much We Read”. It said that Amazon will begin paying royalties based on the number of pages read by Kindle users, rather than the books they download. This system will begin on July 1 and “initially” applies to authors who self publish their books via the Kindle Direct Publishing Select (KDP Select), which makes books available to download from the Kindle library and to Amazon Prime customers.

The article said that if a reader abandons a book a quarter of the way in, the author will get only a quarter f the money they would have earned if the reader had finished the book.

Amazon claims its method is a fair way of rewarding authors who write lengthy books but have previously earned the same as someone who crafts 100 pages. “We’re making this switch in response to great feedback we received from authors who asked us to better align payments with the length of books and how much customers read”, the company said. “Under the new payment method, you’ll be paid for each page individual customers read of your book, the first time they read it.” To prevent authors beating the system by enlarging the type and spreading our their work over a larger number of pages, Amazon has developed a “Kindle Edition Normalised Page Count” which standardises the font, line height and line spacing.

The article mentions Unfinished: Kindle’s most difficult books:

Capital in the 21st Century, by Thomas Piketty: 2.4% completed

A Brief History of Time, by Stephen Hawking: 6.6% completed

Thinking Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman: 6.8% completed

Lean In, by Sheryl Sandberg: 12.3% completed

Flash Boys, by Michael Lewis: 21.7% completed

Also mentioned in the article was data released by Kobo, the Kindle rival, which showed that only 44% of readers finished The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt, which was one of the biggest sellers in 2014.

Hari Kunzru, the award-winning author of The Impressionist, said the system “feels like the thin edge of a wedge.”

Peter Maass, a writer and editor, said on Twitter: “I’d like the same in restaurants – pay for how much of a burger I eat.”

Kerry Wilkinson, whose Jessica Daniel crime series propelled him to the top of the Amazon bestseller list as a self-published author, believes the system is fair. “If readers give up on a title after half a dozen pages, why should the writer be paid in full?” he said. “If authors don’t like it, they don’t have to use KDP Select. It’s opt in, not opt out.” But Wilkinson found it “eerie” that Amazon was keeping tabs on what – and how – you are reading. Even if it’s anonymous, that’s a lot of data mining.”

To Kunzru’s comment, there is no reason this system could not be extended to all Kindle editions, so that whoever holds the copyright (usually the publisher) would be paid on the percentage of a title that is read. And, of course, other e-books (like Kobo) could adopt the same system. So, it definitely sounds to me like the thin edge of the wedge.

I think the system sounds fair for mass market books which are intended for a broad group of readers. I suspect that readers of crime, thriller, romance, historical novels (and other genres) generally finish the books they have bought. But I also suspect that non-fiction books (such as self-help, political, business, nature, science, environment, etc.) are probably not finished in many cases. Does this suggest that their authors deserve a lesser reward? I don’t think so (only one of my published books – from long ago – is in one of the latter categories). A reader may buy a non-fiction book, read 25% of it, and still be pleased with the book: s/he may well feel that s/he got her money’s worth, and in such a case shouldn’t the author get the full royalty?

The other concern I have is about works of top-class, leading edge fiction. The Hawk comes to mind. I suspect that quite a few readers decided that the prose or the subject matter was not for them. This may also be true of works by Salman Rushdie or Jonathan Franzen, where the writing just went over the reader’s head. I suppose that one could argue that if a potential reader had to pay only say 25% of the cost of a book to try it, that would provide the reader with an incentive to buy it and at least try it. And, it would provide the author with at least some compensation. I’ll be interested to hear what the top-class authors have to say about the Amazon scheme. I don’t think they’re going to like it. After all, they’re probably selling a lot of books that end up on the I Once Tried to Read This shelf.

June 15, 2015

Amazon: Friend or Foe?

An article entitled: “Amazon: Friend or Foe? A Simple Question with a Complicated Answer” is in the June 2015 issue of the Independent, the monthly journal of the Independent Book Publishers Association. It is written by Mike Shatzkin, who is CEO of The Idea Logical Company and a publishing industry consultant. His blog, the Shatzkin Files (idealog.com/blog) is the source of the article. I think it is worth summarising Mr Shatzkin’s points.

Mike Shatzkin

Mr Shatzkin begins by saying that Amazon has profoundly changed the publishing industry in three ways. First, it has consolidated the book-buying audience online and delivers it with extraordinary efficiency. For most publishers, Amazon is their most profitable account, if volume, returns and cost of servicing are taken into account. Since this fact is almost never acknowledged, it is “one of the industry’s dirty little secrets”. For this reason, he says that Amazon must feel justified in trying to take more margin, an effort which the publishers resist because they don’t know where the demands will cease. At the same time and in spite of the profitability of the Amazon account, many publishers feel more comfortable with a whole range of customer accounts.

Secondly, “Amazon just about singlehandedly created the e-book business”. They made an e-reading device with built-in connectivity for direct downloading; this was done in pre-WiFi days so that Amazon was taking a risk that connection charges could destroy margins. Amazon had the clout to persuade publishers to make more books available in e-versions, and they had the loyalty of book readers who bought e-books.

Finally, the success of the Kindle made self-publishing attractive. E-books could be produced cheaply and sold at low prices with high margins. It facilitated the process by creating an easy-to-use interface and efficient self-service. Amazon represented a ready market for self-published e-books.

Shatzkin says that the first two of these three changes made Amazon a friend of the traditional publishing industry, while the third puts them more in the category of foe.

He goes on to say that Amazon’s data policies make them a foe: they do not share information. Amazon does not use the industry standard identifier, the ISBN, for the titles that it publishes: it uses the ASIN and does not report on the volumes or the categories of ASIN’s. There is a black hole in the data.

Amazon also does not report on its sales of used books. The used book market may help publishers sell more new books as the used book market offers a means for buyers to get a portion of their investment back. But at the same time, when used versions are available almost simultaneously with new books, they represent a downward pressure on new book prices. Over time, as demand for a given title decreases and the volume of used copies for sale increases, the price of used copies will decline. But only Amazon has the useful data about the used book market.

Traditional publishers have no idea how large Amazon’s proprietary book publishing business is. What volumes? What categories? How will recently published Amazon titles affect the prospects for titles under consideration by traditional publishers?

Shatzkin says that Amazon never saw the book business as a stand alone business. Rather, it was focused on creating “life-time customer value” across a broad range of products. While it clearly dominates the English-speaking book world, language differences mean that book markets will remain ‘local’ for a long time and strong local players will be hard to dislodge.

He says that the Kindle and Amazon Prime are powerful tools to retain customer loyalty. Once one subscribes to Prime, all shipping charges are waived, removing the incentive to buy from others. And, of course, Amazon has the world’s largest selection of printed and digital books in one place.

Looking ahead, Shatzkin sees the subscription services, such as Scribd, Oyster, 24Symbols and Bookmate (as well as Amazon’s own Kindle Unlimited) as pulling customers away from á la carte book buying. Most of these sales will come out of Amazon’s hide.

His conclusion: Amazon will remain dominant in most of the world for the foreseeable future. Although, with the next round of marketplace changes, Amazon will be challenged as it will dominate a small portion of the overall market.