Jamie Todd Rubin's Blog, page 3

July 4, 2025

Proof Through the Night

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died 199 years ago today. I once wrote a time-travel story where, on their dying day, Adams and Jefferson were brought together on the shores of New Jersey to watch the fireworks display at the Bicentennial celebration in New York City, and to see proof through the night that the flag was still there.

I sent the story off to a magazine to which I’d sold stories before and the editor sent me a note saying he liked the story, but something about it didn’t quite work. He couldn’t place his finger on what it was so he was going to pass on the story. I mentioned this to a writer friend of mine, who said, “Send me the story; I’ll tell you what’s wrong with it.” So off went the story, and a short time later, my friend wrote back, “Well, I read the story, and I liked it, but there’s something about it that doesn’t quite work, and I can’t tell you what it is.

On Independence Day, I often reflect on what the founders of our nation would think of what we have become, nearly 250 years later. Could they imagine traversing the continent in five hours? Would they be astounded that a trip to Paris or London would take less than a day, when it took them at least a month at sea each way? Mail (of the electronic variety) is now instantaneous. Medicine is light years ahead of where it was in 1776. We sent people to the moon! Of these I think they would be impressed.

But what of our stewardship of the constitution they created? I’ve read biographies of many of the founders. I’ve read their diaries and letters. For some, I feel as if I know them as friends. And yet I am not sure what they might think of the job we’ve done over the last 249 years. I frequently imagine bringing John Adams and Thomas Jefferson back to life in 2025 (not so different from how Jason Heller imagined bringing Taft back in 2012). What would they think of our republic? What would our leaders think of them upon meeting them in person, and being able to ask them the questions: Is this what you imagined? Did we do it right?

Perhaps after looking around and talking to people, they, like my editor and friend, would say that they liked much of what they saw and heard, but that there was something that didn’t quite work, and they couldn’t tell us what it was.

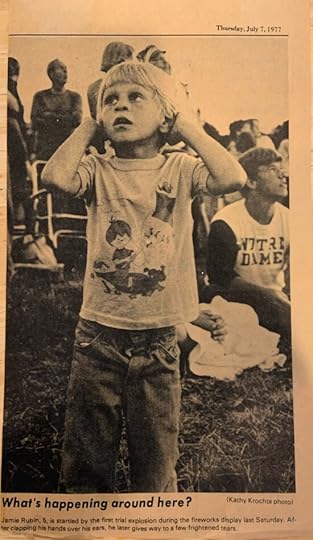

Me, in 1977, at an Independence Day celebration in New Jersey.

Me, in 1977, at an Independence Day celebration in New Jersey.About / Contact | Bibliography | What I Have Read Since 1996 | Curated Index to the Blog

FacebookInstagramJuly 2, 2025

Cursive Aggressive

Though I dutifully filled out all of the forms online ahead of time, when I arrived for a recent medical visit, the receptionist handed me a dreaded clipboard and asked me to “fill out the highlighted parts.” This caught me in a Puckish moment. I proceeded to fill out all of the parts so indicated in a quick and mostly illegible (except to me) cursive hand. The only place I reluctantly printed was where the form indicated “Print Your Full Name Here” in a Germanic and unnecessary camel-case.

I returned the form and sat, waiting for the receptionist to hesitantly tell me that they could not read what I had written and could I please print my responses. But I was called back to see the doctor before being discovered and thus quickly made my escape.

About / Contact | Bibliography | What I Have Read Since 1996 | Curated Index to the Blog

FacebookInstagramJuly 1, 2025

Montaigne’s Melancholy

To escape the heat, I dragged a reluctant Montainge downstairs, where it was cooler, and collapsed into a comfortable chair beneath the breath of an air conditioner vent. Montainge was going on about sadness, but I muted him beneath the book cover and sat listening to my youngest daughter sing in the shower in the nearby bathroom. I couldn’t quite make out what she sang, but she sounded happy, and that added a nice balance to Montaigne’s melancholy.

About / Contact | Bibliography | What I Have Read Since 1996 | Curated Index to the Blog

FacebookInstagramMorning Music

The best part of my early morning walks in summer is pausing under this goldenrain tree. If I am listening to a book or music, I pause the audio and stand still, listening. The tree hums. The bees pollinating the flowers in the crown seem to harmonize so that the tree sounds like some kind of organic electrical transformer.

I missed my morning walks for about a month, and I’m glad I’m back at it. The bees’ morning music has become part of my summer wake-up routine.

About / Contact | Bibliography | What I Have Read Since 1996 | Curated Index to the Blog

FacebookInstagramApril 27, 2025

Shelf-Life #10: Our Oriental Heritage

This post is part of my weekly series, Shelf-Life. Each episode is about a particular book on my bookshelves. For more information see my introductory post. To read other episodes in this series, see the Shelf-Life Index page.

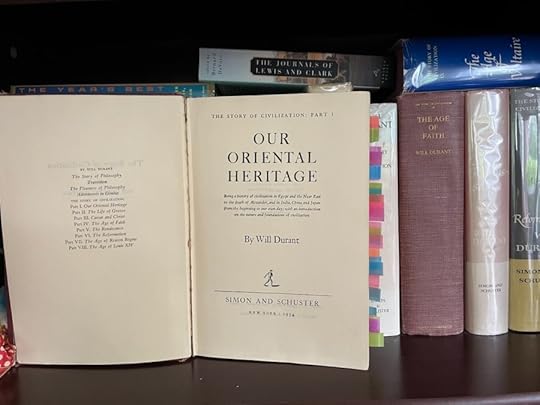

My grandfather got me my well-worn edition of Our Oriental Heritage back in April 1999, from a used bookstore in Nyack, New York. Our Oriental Heritage was the first volume in what historian Will Durant thought would be a 5-volume survey of civilization called THE STORY OF CIVILIZATION. It was published in 1935. I first heard of the book while reading the first volume of Isaac Asimov’s autobiography In Memory Yet Green, probably sometime in 1995.

The book my grandfather sent me was a 1954 edition and nineteeth printing of the book. It arrived without a dust jacket, making it one of three books in the series that I own without a dust jacket. I don’t mind this. I tend to hang the jackets in the coat closet when I read the book. I want them to be comfortable and stay a while. It arrived with the aroma of 45 years of use and used bookstores. It is a smell that, like the first sweetness of spring, makes the olfactory sense a delightful one. Unlike spring, however, the aroma doesn’t fade but grows richer with time.

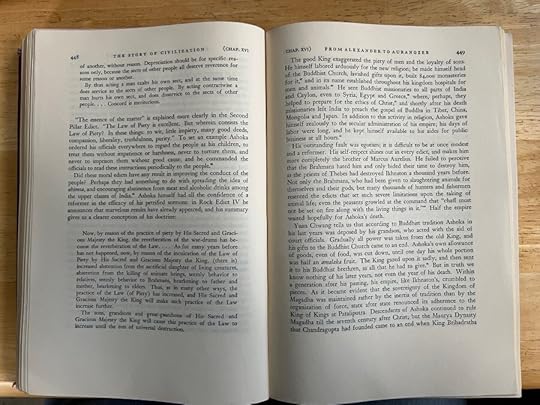

This book, as a physical object, is sumptuous. It has generous margins, as if Durant and Simon & Schuster were inviting readers to mark up the text, converse with Durant, or ancient writers, philosophers, warriors. I made heavy use of this precious commodity, and I wish more books allowed for this, but today we optimize for maximum text with minimum paper.

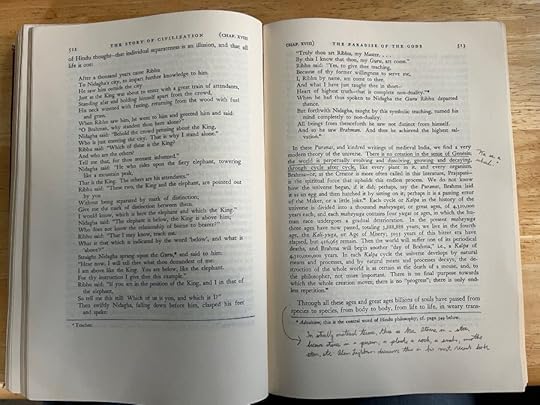

The sumptuous margins of Our Oriental Heritage

The sumptuous margins of Our Oriental Heritage Me, taking advantage of the sumptuous margins.

Me, taking advantage of the sumptuous margins.I particularly enjoy large books. There is nothing like sitting down to start a 1,000-page book, knowing that you have this long journey ahead. Patience is required. It doesn’t always cooperate. I first attempted to read Our Oriental Heritage on May 4, 19991, probably soon after it arrived in the mail from my grandfather. But I didn’t finish it. I didn’t actually return to the book and read the whole thing through until nearly ten years later. In the meantime, I read the second volume in Durant’s STORY OF CIVILIZATION series, The Life of Greece and that is probably where I fell in love with Durant’s writing.

With this series, and with this first book as trial, Durant was attempting to write what he called an “integral history.” As he wrote in the preface to Our Oriental Heritage:

I have long felt that the usual method of writing history in separate longitudinal sections–economic history, political history, religious history, the history of philosophy, the history of literature, the history of science, the history of music, the history of art–does injustice to the unity of human life; that history should be written collaterally as well as literally, synthetically as well as analytically; and that the ideal historiography would seek to portray in each period the total complex of a nation’s culture, institutions, adventures, and ways.

So “integral” as in integrating all parts of history into the whole narrative. Or even in the calculus sense as the area under the curve, encompassing everthing there. This intrigued me.

Moreover, Durant’s style of historiography was like nothing I’d ever encountered before. He was writing history as literature. Prior to Durant, history for me, while always interesting, was little more than dates and names, winners and losers, risings and fallings. There was a lot of this in Durant’s book, but he used it to paint a picture. In Durant’s hands, history became a force that bound the dates and names and events and creations together.

His classic style put his theses at the end paragraphs, rather than the beginnings, often in clever or ironic ways:

Man differs from beast only by education, which may be defined as the technique of transmitting civilization.

Or, for instance, while discussing pregnancy in some culture, tells the story of how a woman becomes pregnant through a ghost, and concludes:

It is a delightful story, which must have proved a great convenience in the embarrassing aftermath of generosity; it would be still more delightful if it had been invented for anthropologists as well as for husbands.

Or, when writing of the toilers of Babylonia:

Part of the country was still wild and dangerous; snakes wandered in the thick grasses, and the kings of Babylonia and Assyria made it their royal sport to hunt in hand-to-hand conflict the lions that prowled in the woods, posed placidly for artists, but fled timidly at the nearer approach of men. Civilization is an occasional and temporary interruption of the jungle2.

This first volume covers ancient civilizations to the death of Alexander as well as the history of India, China, and Japan from their beginnings to the present. Even at a thousand pages, the book was necessarily general, especially when considering the integral history style and the scope it covered. As I read through subsequent volumes, I noted that each had a smaller scope and a more detailed view of its subject. The Life of Greece was tightly focused around Greek civilization. The next volume, Caesar and Christ tightened its focus on to the Roman civilization and the birth of Christianity. With each volume, the scope narrowed, and grew more detailed, throwing Durant’s original plan of five volumes out the window. Ultimately, the series concluded with 11 volumes. The eleventh and final book, The Age of Napoleon centered around the French Revolution and Napoleon.

It wasn’t obvious at first, but Our Oriental Heritage was a zoomed-out look of the birth and initial growth of civilization. Each book zoomed in more and more. There was a greater resolution with each book. We began with a fifty thousand foot view of human civilization and concluded with a book that centered around a single man.

This richness of history has captivated me. It is literature that, when in capable hands, can tell the story of civilization as Durant did; or it can tell the story of a single person or thing, for instance as John McPhee did in his book Oranges. This latter is a short book that tells the history of the fruit from every possible angle, from origins to how it ends up in a glass of juice with breakfast.

Over the years, it has made me wonder: if the Drake equation is right, and there are millions of advanced civilizations scattered throughout the universe, some of the millions of years old, what would their histories look like? Our Oriental Heritage goes back 6,000 years to the birth of civilization. Imagine going back millions of years of rich history. Imagine the alien myths that arose 900,000 years earlier, the foundational texts, the literature, the love stories, the birth of science in a manner completely different from our own, the art, the philosophy, all of it from a broad overview, down to the story of one pivotal being.

When asked what my “desert island” book would be, I cheat a little, and answer “Will and Ariel Durant’s STORY OF CIVILIZATION.” I mean, of course, the whole story, all 11 volumes. With 6,000 years of predecessors, with 6,000 years of literature, art, history, science, philosophy, one could never feel alone on a desert island.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

︎Emphasis mine.

︎Emphasis mine.  ︎

︎

April 20, 2025

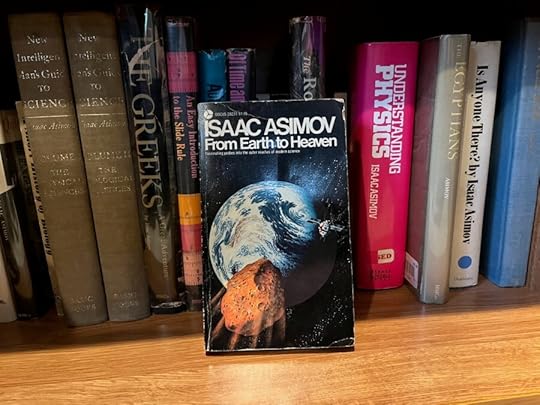

Shelf-Life #9: From Earth to Heaven

This post is part of my weekly series, Shelf-Life. Each episode is about a particular book on my bookshelves. For more information see my introductory post. To read other episodes in this series, see the Shelf-Life Index page.

If one were to peruse the list of books I have read since 1996, the first item of note might be the book that started it all, #1 on the list: From Earth to Heaven by Isaac Asimov. Why this book? Why the list? Why now? In other words, how did it all start?

In late 1995, I made a spur-of-the-moment decision: I would try to read one book every week, or 52 books per year. This wasn’t a New Year’s resolution, but it was a definite goal I set for myself. In order to help keep me on track, I decided that in 1996, I would begin to keep a list of all of the books I read. I was inspired, in part, by a list I saw online by a reader named Eric W. Leuliette sometime in 1995. My idea was to write down each book I finished and give it a number. If I didn’t finish the book, it didn’t go on the list.

The very first book on my list was Isaac Asimov’s science essay collection From Earth to Heaven, which I finished reading on January 13, 1996. As far as I know, this is the first collection of essays I voluntarily read for pleasure, and this was the beginning of my love for the essay form.

Given that the book was a collection of monthly science essays, the contents were eclectic, with Asimov’s interests varying from month-to-month in his column. The seventeen essays in the collection covered a wide range of scientific topics. “Oh East Is West and West is East–” discussed latitude and longitude. “To Tell a Chemist” covered Avogadro’s number. “Behind the Teacher’s Back” discussed the uncertainty principle. “Death in the Laboratory” was all about fluorine. “The Land of Mu” discussed mesons, while “The Rock of Damocles” was all about earth-grazing objects like asteroids. Asimov approaches all of these topics colloquially, often with humor, and always starting at the beginning so that the subject is always clear. Reading the book, I found interests pulled in seventeen different directions.

I’m certain, for instance, that if it were not for Asimov’s science essays, it would never have occurred to me to read David Berlinski’s A Tour of the Calculus, a book I read a short time later. And if I hadn’t read and enjoyed those essays, I might never have discovered my love for the essay form. Ever since, I’ve been on the lookout for good essay writers. I discovered Andy Rooney’s essays, which I loved. Later, I discovered E. B. White’s “One Man’s Meat” and other essays. Then Stephen Jay Gould, whose “This View of Life” appeared in Natural History magazine for 300 consecutive issues. Then David Foster Wallace, Christopher Hitchens, Gore Vidal…

I can’t get enough of the essay form, and I have Asimov’s From Earth to Heaven to thank for that. Asimov’s writing is clear and straightforward. It has been a pleasure to move from that to other styles. The most difficult to penetrate (but just as rewarding) are those of Stephen Jay Gould. His essays are like puzzles, and it is a joy to spend the time understanding them. Andy Rooney’s pieces were, in retrospect, heavily influenced by E. B. White. White, my favorite, is the true master of the form. I’ve read individual essays from other writers that are better than some of White’s, but in aggregate, I’ve yet to read another essayist who consistently maintains beauty of substance and style in White’s writing.

It recently occurred to me that books are like seeds. Plant them, and they grow, their branches reaching out in all different directions leading a reader this way and that. If that is the case then From Earth to Heaven is the first seed I planted in a garden that has grown to more than 1,400 trees, their branches arching and intertwined like the buttresses of some massive jungle cathedral. My list, then, is a record of my garden, an almanac of seasons of sowing and reaping, of planting seeds of knowledge and watching them grow and expand. The garden is larger than I could possibly imagine three decades ago when I first started to cultivate it. Its diversity of subject is among my greatest joys in its cultivation. The only greater joy is the knowledge that in this type of garden, there are no limits of space, only time. It can and will continue to grow, and I’ll continue to spend the seasons sowing and repeating for as long as I have seasons left to spend.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

April 13, 2025

Some Things I Learned In High School

I’m not normally one for prompts, but I saw prompt the other day asking about something the writer learned in high school. I found myself thinking about it throughout the day, and jotting notes to myself about things I’d learned in high school. Here are ten of them.

You can have an opinion about what you read. Shakespeare wasn’t perfect.The five paragraph essay is the training wheels for critical thought. Practice so that you can abandon the training wheels.It may be impossible to cross a room if you go by way of halves.You don’t study for a test. You study for the future.It is amusing to watch an English teacher teach English grammar with a straight face.An all-nighter is a great idea at 3pm and a terrible idea at 3am.The first time I learned about the Krebs cycle is the 100th time the biology teacher taught it. Have some perspective.If you wanted to get blasted add water to acid. Do like you oughta, add acid to watah.Read all of the instructions first and avoid wasting a lot of time later.High school resmbles the real world, if the real world involves sitting in a series of hour-long meetings all day long, and getting your work done at home in the evenings.Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

No Shelf-Life Post This Week

I am on a long-weekend getaway with the family after a very busy week. I got this week’s Shelf-Life post partially written, and then was up early this morning working on it some more by the fireplace in the resort lobby. But I felt like I was rushing things when I should be taking my time and enjoying myself. Reluctantly, I decided to take the week off from the series. It will resume next Sunday, April 20 with Episode 9.

If you are new to the series, or looking to catch up on some you may have missed, now is an excellent time to go through the previous episodes.

April 11, 2025

What He Really Wants to Do Is Direct!

Even as I scramble my way through books, and write posts on productivity, life continues, a river wholly unconcerned with my mundane thoughts and opinions. There is no PAUSE button to keep the kids from growing up while I’m engaged in these activities. Remember the Little Man? He has grown into a strapping teenager, taller than his mother, with a Timothée Chalamet head of hair, who among other things has become a talented stage actor—and now, a director.

Those interested can “meet the director” in this brief interview posted today by Encore Stage & Studio.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

April 6, 2025

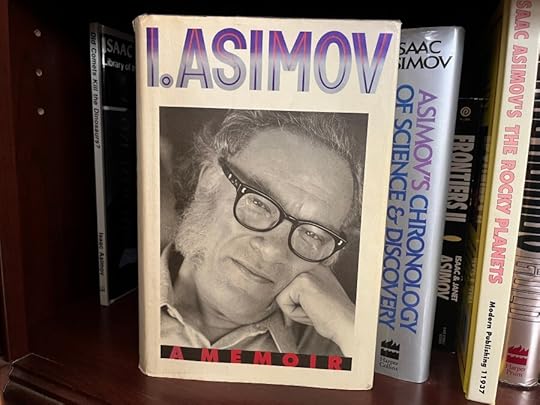

Shelf-Life #8: I. Asimov

This post is part of my weekly series, Shelf-Life. Each episode is about a particular book on my bookshelves. For more information see my introductory post. To read other episodes in this series, see the Shelf-Life Index page.

April 6 marks a special anniversary for me. On April 6, 1996, I began to keep the diary which I still maintain today. Four years earlier, on April 6, 1992, Isaac Asimov died. The two events are most definitely related, as we shall see.

Sometime in the early spring of 1994, while wandering through a bookstore in Moreno Valley, California, I saw prominently displayed a book with a white cover and Isaac Asimov’s face on it. The title read: I. Asimov: A Memoir. Something about the book attracted my attention. Up to that point, I’d heard of Isaac Asimov, and when I was around ten or eleven years old, I’d attempted to read his novel, The Caves of Steel. I knew vaguely that he was a scientist as well as a science fiction writer. That was the extent of my knowledge. And yet, despite the $25 cover price, I bought the book. I took it back to my apartment at the campus of the University of California, Riverside, and I began to read it. In the 31 years since that day, no other book, not one, has had as much of an impact on my life as that one.

It turned out that Isaac Asimov had already published a massive autobiography, a two-volume, 600,000-word work published in 1979 and 1980 called In Memory Yet Green and In Joy Still Felt. This new volume was different. As Asimov wrote in the introduction:

What I intend to do is describe my whole life as a way of presenting my thoughts and make it an independent autobiography standing on its own feet. I won’t go into the kind of detail I went into in the first two volumes. What I intend to do is break the book into numerous sections, each dealing with some different phase of my life , or some different person who affected me, and follow it as far as necessary—to the very present, if need be.

I trust and hope that, in this way, you will get to know me really well, and who knows, you may even get to like me. I would like that.

Thanks to this memoir, that is exactly what happened to me. I got to know Isaac Asimov really well. Better, perhaps, than any other writer I have read. What’s more is how much I learned from him. Yesterday, I scribbled a list of what I’d learned from Asimov and it is easy for me to see, at least, that I would be a completely different person without those lessons. And all of this from someone who had, alas, been dead for nearly two years when I first sat down to read the book.

What exactly did I learn?

The most obvious outward example is my own writing style. Asimov’s style was unadorned and colloquial, and that was a huge influence on my own writing. Most writers I know are influenced, in some way or other, by the writers they read, but over time, they develop their own voice. Mine traces directly back to Asimov’s. Like a good impressionist, I can impersonate other styles. I did this most publicly in my story, “Hindsight in Neon” which appeared in an early issue of Apex Magazine. There, I was deliberately imitating Barry N. Malzberg’s style. But the style I tend to write in, my default mode, what you are reading now, is adapted from Asimov’s style.

I think it has served me well. I’ve sold stories, to say nothing of two lead editorial articles in Analog using my natural style. I’ve written over 7,000 blog posts in this style. If you’ve ever received an email from me, you’ll no doubt note that it is written in this style. It has become the way I naturally communicate.

It was from I. Asimov, and its two predecessor volumes, that I learned how to be a professional writer. I’m not talking about how to write professionally. I’m talking about to conduct oneself as a professional writer, how to work with an editor, what galleys were, what the unwritten rules of professional writing were. I would have known none of this. Indeed, until reading this book, my ideas of an editor came from Piers Anthony’s “Author’s Notes” where he considered editors idiots if they changed a word. Fortunately, I had Asimov to teach me better, and all of my interactions with editors have been great experiences, ones where I try to learn as much from each as I possibly can.

I read I. Asimov for the first time as the final quarter of my senior year in college was starting. I was taking an extra heavy load (24 credits—this required special approval from the Dean), and continued to work in the dorm cafeteria. One of those courses was a “healthful living” class required by my major. During that class, we had to get up in front of the entire class and give talk on a particular health-related subject. I never liked getting up in front of people and speaking. Isaac Asimov turned me around on that.

If I allow my original copy of I. Asimov to fall open at random, chances are good that it will fall open to a section titled “Off the Cuff” where Asimov details how he became a public speaker and how he tends to deliver his talks. He talks about discovering this latent talent. He had no idea he could speak in front of audiences (and off the cuff, at that) until he tried it. What, he wondered, would have happened had he never discovered this talent? I read this section over and over again, and when it came time for me to give my talk to the health class, I did it off the cuff.

I’d like to say that it went smoothly. Mostly, it did, but I had a punchline I’d intended to deliver, and when it came time to deliver it, my mind went blank. I had nervous few moments, but I got through it. And afterward—I never worried about addressing an audience again. Early in my career, I had to give a talk on a new browser called Netscape Navigator to a roomful of researchers. I prepared well, but I still delivered the talk off the cuff. Afterward, I received an email from one of the attendees, none other than the computer pioneer Willis Ware, who complimented me on my talk with a ”GOOD SHOW!” Much later, I was even paid for a couple of talks I gave to some business leaders. Without reading I. Asimov, I’m not sure I would have ever tried something like that.

There are other things I learned from Asimov that stemmed from this book. I’ve written in the past how nearly everything I learned about science I learned from Isaac Asimov. His memoir led me to his science essays which he published monthly in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction for over 30 years. These essays were collected into nearly two dozen volumes, and I read through them voraciously. There are fascinating facts and figures and speculations in essays, but much of what I learned was how to explain things in a way other people can understand them.

I admired Asimov’s generalist approach to learning and his humanist approach to thinking, both of which set me on similar courses.’

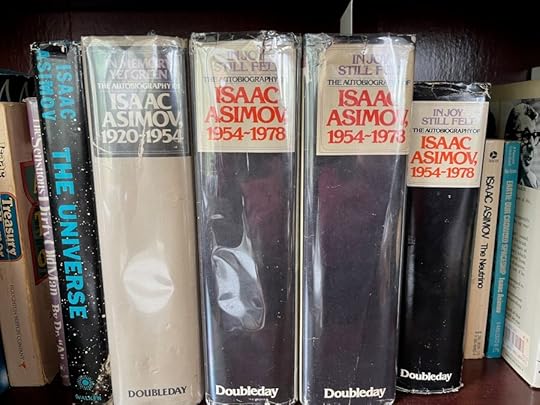

Isaac Asimov died on April 6, 1992. His wife, Janet, describes the end in the memoir. Reading it today, I still feel a pang. How I wish I could have known him in person! As I’ve said, I first read I. Asimov in the spring of 1994. I think I read it again in 1995 but I’m not certain because that was before I started keeping my list. In the meantime, I managed to obtain used copies of his previous autobiographies, and I made my way through those. In some ways, they were better because they were even more detailed.

In 1996, I had a plan. I’d start to read I. Asimov around my birthday in late March, with a goal of finishing the book on April 6, the fourth anniversary of Asimov’s passing. By the end of the book his wife, Janet, is describing his last days, which makes for a sad way to end. I didn’t want to end that way. Instead, I decided that after I read I. Asimov, I’d re-read In Memory Yet Green and In Joy Still Felt so that when I finished those books, it would only be 1980 in Asimov’s life and would be like he’s still living.

My copies of Asimov’s earlier autobiographies. One of the copies of In Joy Still Felt is a first edition. The other is signed by Asimov.

My copies of Asimov’s earlier autobiographies. One of the copies of In Joy Still Felt is a first edition. The other is signed by Asimov.That year, I did finish reading I. Asimov on April 6. I didn’t start the other books until May. In subsequent years, however, I would re-read all three books, finishing I. Asimov on or close to April 6 and then spending the rest of April reading the two earlier volumes. It was heaven and I looked forward to this “renewal” in spring each year.

Two of my fondest reading memoirs involve these books. In one, I’m sitting on the porch of my Studio City apartment, chair propped back, with I. Asimov in my lap and the warm Southern California sun on my face. In the other, I’m seated at a booth in Swenson’s on Laurel Canyon and Ventura Boulevards, sipping at a chocolate shake, and reading about Asimov’s early days in his parents’ candy store in Brooklyn in the first volume of his autobiography.

From 1996 to 2008, I never missed a year when I read all three books. If we include my 1994 and 1995 reading of I. Asimov, I’ve read that book 17 times. The last time I read it was in April 2010—except that I am finally reading it again now, and I expect to finish it today or tomorrow. What a pleasure it has been to come back to it.

The book has influenced me in two other significant ways. When I decided to re-read it in 1996, I told myself that when I finished it, I’d start a diary of my own. Asimov started a diary when he was 18 and continued the practice through his life. For him, the diary was just another reference book. That made sense to me. The opening sentence of my very first diary entry, written on Saturday, April 6, 1996 was:

I finished I. Asimov this afternoon at about 4pm, precisely as I had hoped to do.

Twenty-nine years later, and that practice continues.

Reading Asimov also saw me branch out to other writers that I might not otherwise have read, or perhaps, would have read much later than I did. Carl Sagan was one. Asimov and Sagan were friends (indeed, Sagan was one of two people that Asimov would freely admit was smarter than he was. The other: Marvin Minsky.) I started scrambling my way through Sagan’s books beginning in December 1996, and like Asimov, much to my dismay, I’d learned Sagan had died shortly before I started reading The Demon-Haunted World.

Asimov described style as mosaic or plate glass. A dense writer is like a mosaic window in a church, while plate glass is clear, and you don’t even notice it is there. Asimov introduced me to Stephen Jay Gould, whose essays I adore, but are mosaic when compared to Asimov’s plate glass style.

He introduced me to Agatha Christie and P.G. Wodehouse and Martin Gardner and Will Durant and his Story of Civilization. In countless ways he has influenced me, first and foremost through his memoir, I. Asimov. Though I never met him in person1, when I read his memoir, or his autobiography, or his science essays, or his guide to the Bible, or his Annotated Gilbert & Sullivan, he is alive for me. His voice speaks to me alone. I think I am a better person because of him.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

︎

︎