Matt Moore's Blog, page 3

June 12, 2018

Longlisted for the Sunburst Award and Finalist for the Aurora Aurora (times two!)

In the space of a few days, I learned I’m a finalist in two categories for the Aurora Awards and been longlisted in the Sunburst Awards’ short story category.

Aurora Awards

The Aurora Awards are the leading fan-voted awards for Canadian speculative fiction, poetry, art, organizations, fan activities, and more. This year, I’m a finalist in two categories:

Best Fan Organizational for my work with the Ottawa Chiaroscuro Reading Series

Best Poem for “Heaven is the Hell of No Choices” that appeared in Polar Borealis #4

This makes a total of eight times I’ve been an Aurora Award finalist.

This is my fifth time in Best Fan Organizational for the Ottawa ChiSeries

My first time for poetry

I was nominated in the Short Story category twice: “Touch the Sky, They Say” from AE: The Canadian Speculative Fiction Review (2011), and “Delta Pi” from Torn Realities (Post Mortem Press, ed. Paul Anderson)

I’m grateful to my co-chair Marie Bilodeau and Nicole Lavigne, plus Brandon Crilly who stepped up at the end of 2017, for making ChiSeries Ottawa a reality.

Any Canadian—which includes citizens in Canada and abroad as well as long-time residents—can nominate works and then vote when the finalists are announced. You need to join the Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Association, which costs $10 per year. Membership gets you access to a Voter’s Package, which contains electronic versions of the finalist works.

Voting in the Aurora Awards opens July 28, 2018 and closes September 8th, 2018. Winners will be announced at VCON in Richmond, BC on October 5-7, 2018.

Sunburst Awards

The Sunburst Awards are the leading juried awards for Canadian speculative fiction with categories for novels, young adults novels, and short stories. My short story “Good-bye is that Time Between Now and Forever” from The Sum of Us (Laksa Media Group, ed. Susan Forest and Lucas K. Law) has been named in the longlist of finalists.

The jury will narrow the longlist down to a shortlist in late June. The winners will be announced in Fall 2018.

June 11, 2018

Radio interview with Kate Heartfield and me now online

Last Thursday, June 7, my friend and fellow Ottawa writer Kate Heartfield and I were interviewed on Literary Landscapes, a weekly radio show on CKCU FM—the radio station of Carleton University in Ottawa.

You can now listen to that radio interview of Kate and me. Just click the “LISTEN NOW” link (next to “ABOUT”—sorry, the page has a lot of navigation) for a pop-up window that contains the interview. No download link, unfortunately.

Kate and I cover a lot of ground in this interview, including:

Working with a mid-sized press (ChiZine Publications)

Getting our start as first-time authors over 40

Horror vs fantasy

Our upcoming book launch on Thursday, June 14

June 7, 2018

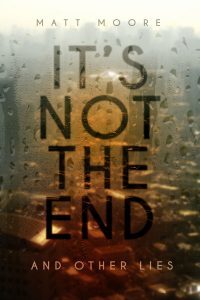

It’s Not The End and Other Lies is NOT cancelled!

If you ordered my book It’s Not The End and Other Lies from Amazon.ca, and Amazon.ca says the book has been cancelled, AMAZON LIES!

If you ordered my book It’s Not The End and Other Lies from Amazon.ca, and Amazon.ca says the book has been cancelled, AMAZON LIES!

Somehow, Amazon.ca got its wires crossed when the release date got pushed back. The book is real, it has been published, and you should be able to buy from these others sites:

Amazon U.S.

Amazon U.K.

Barnes and Noble

Book Depository

Books-A-Million

Chapters-Indigo

IndieBound

Powell’s

If you prefer to order from Amazon.ca, it should be back up for sale in a week or so.

May 23, 2018

Ottawa Book Launch with Kate Heartfield! June 14 at Patty Boland’s

I’m excited to tell you that my good friend and fellow Ottawa writer Kate Heartfield and I will be launching our debut books, both from ChiZine Publications, on June 14 at Patty Boland’s in Ottawa’s Byword Market! We run from 5:30 – 8:00, but drop in anytime. Throughout the evening, we’ll have readings, raffles, prizes and who knows what else.

This event is hosted by ChiZine Publications and we’ll also be having the Ottawa launch of the rest of their spring titles with books by George A. Romero (yes, that George A. Romero), Brian Hodge, Kate Story, Amanda Downum & Scott A. Ford. Check out their Spring 2018 catalogue.

Tell us your coming on our Facebook event

Details

When:

Thursday, June 14

5:30 PM – 8 PM

Where:

Patty Boland’s

101 Clarence Street

Ottawa, Ontario

On Google Maps

About the books

Armed in Her Fashion is a dark historical fantasy about a wet-nurse in 14th-century Flanders who leads a raid into a Hellmouth to get her money back from her dead husband.

More information and ordering details on ChiZine Publications’ website

It’s Not The End And Other Lies mixes science fiction and horror to explore the line between the humane and the monstrous, the breaking point of the human spirit, and the challenges the near-future may bring.

It’s Not The End And Other Lies mixes science fiction and horror to explore the line between the humane and the monstrous, the breaking point of the human spirit, and the challenges the near-future may bring.

More information and ordering details on ChiZine Publications’ website

May 22, 2018

New Workshop: Getting to “Yes” in Traditional Publishing

I’m trying to sell my novel… and everyone says “no”!

I’m trying to sell my novel… and everyone says “no”!I’ll be running a workshop at Limestone Genre Expo in Kingston, ON on May 26 – 27. It takes place on Sunday, May 27 from 3:00 – 5:00 pm in the Sir John A. Macdonald Room. This workshop is free with your pass to the convention.

Getting to “Yes” in Traditional Publishing takes a look at a common problem authors face: your novel (or short story collection or graphic novel) is done, your friends tell you it’s great, you’re making pitches and submissions… but no publisher is interested.

It might not be your work.

It might be how you are presenting yourself.

Having a great manuscript will only go so far. Publishers, editors, agents and other industry professionals want someone they can have a productive and respectful relationship with. While some might be willing to nurture your career, none will hand-hold you through the entire publishing process. Publishing is a business relationship; like any relationship, you need to meet them halfway. How you present yourself is as important (or more so) than the work you are presenting.

“Getting to ‘Yes’ in Traditional Publishing” explains what you should do for publishers and industry professionals to take you seriously and be more likely to say “yes” to your submissions and pitches.

Getting to “Yes” in Traditional Publishing

Sunday, May 27

3:00 – 5:00 pm

Sir John A. Macdonald Room

May 9, 2018

Limestone 2018 Schedule

10 – 11 am: World-Building: What Makes A World Feel Real (moderator)

Bellevue South

A look at the different ways that authors can make imaginary worlds come to life and why they sometimes fall flat.

11 am – Noon: Reading from It’s Not the End and Other Lies

Martello

I’ll be reading stories and selections from my new short story collection It’s Not the End and Other Lies.

3:00 – 4:00 pm: Mental Health Representation in Fiction: More than Villains

Bellevue South

The “deranged” baddie has been overdone, and used to reinforce negative stereotypes. How does today’s writer change this?

4:00 – 5:00 pm: Crossed genres: How to make it work (moderator)

Bellevue South

Paranormal romance, historical fantasy, a futuristic mystery. Your story can be more than one genre, but making them blend isn’t always easy.

7:00 – 9:00 pm: A Night with Michael Slade (host)

Location TBD

Reading, interview and Q&A with crime-horror hybrid novelist Michael Slade.

Sunday

11:00 am – Noon: Film Tropes Are Killing Your Prose

Bellevue South

The jump scare. Pages of witty repartee. Endless detail describing how cool something looks without saying how it feels. Slavishly following 3-Act structures. Never before has so much visual entertainment been so accessible. But is it killing your prose? Let’s talk about movie and TV tropes and clichés making their ways into prose, and how to stop them.

1:00 – 2:00 pm: Genre 101 for Writers

Bellevue North

Writers of a particular genre to talk about the tropes, mechanics, clichés and essentials of their genre to help other writers.

3:00 – 5:00 pm: Workshop: Getting to “Yes” in Tradtional Publishing

Sir John A. Macdonald

Your novel is finished, your beta readers says it’s great, but publishers keep saying “no”. The problem might not be your work, but your pitch. Publishing is a business, and publishers, editors and agents want great works and good business relationships. If you’re trying to sell a novel, story collection, screenplay or graphic novel, come learn how to make your work stand out by showing you’re an author who professionals can work with.

December 31, 2017

Write your big scenes, connect them later

Star Wars: A New Hope is an almost perfectly structured story, thanks in no small part to Lucas following Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

But it wasn’t always so. This short, excellent video shows how the original cut of the film didn’t have the same pacing and structure as the the finished product. (Which might explain why Episode I – III were so clunky, and fan edits so superior.)

How does that affect us as prose writers?

Remember what Ernest Hemingway said: “the first draft of anything is shit” and “the only kind of writing is rewriting”. Taking a lesson from this video, revising your first (or fourth) draft might not need major re-writes to fix or improve your story. Re-arranging scenes as they were written can improve tension and pacing.

Or, if you are writing your first draft, write the major scenes that you have firmly in mind, arrange them in the order they take place, and worry about “connective tissue” later—how characters move from Point A to Point B, expository conversations, etc. You might find that there is enough information in these scenes that the connecting scenes are extraneous and may have been cut anyway had you written them.

This also means you don’t have to write everything in your first draft. You might write “They go to the cabin” for a scene that you know, in the final story, will be 2000 words or two chapters. But, while writing, you don’t have that scene firmly in mind. Or, that scene as envisioned is boring—stakes don’t change, nothing new is learned, characters don’t develop. So, rather than slogging through it, write a short note of what happens and move on to those scenes that are vivid in your mind. It could be that what happens at the cabin will help inform the story of how they get there—clues, foreshadowing, red herrings—giving you the energy to write the scene that had been lacking.

You can also write out of order. Know what the climax is step-by-step? Write it and leave yourself notes of what information, actions and characters beats need to happen to get there. Write those exciting middle sequences that you’re not sure what they connect to, but they are great in themselves.

But we sure to tie it all together in the final product—logical plot progression, character development, a cohesive story. That part doesn’t change. It’s just that a non-linear way to writing might be the best way sometimes.

Advertisements

December 13, 2017

How to understand what reader feedback *really* means (2/2) – Endings

On November 21, I gave a short story writing workshop with Lydia Peever to the Ottawa Independent Writers. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to cover everything we wanted.

One of the things I wanted to discuss was how to translate feedback you might get from readers or editors into ways to identify problems with your story. In other words, what they really mean and what can you do about it.

I posted earlier about the beginning and middle of a story. Now it’s time to look at the end of your story. While beginnings are delicate (just ask Princess Irulan) and middles can be tricky, the purpose of the story’s end is to tie everything together. When it doesn’t, you might hear…

“That ending came out of nowhere”

What they are really saying: There was no set up that we were heading for the climax.

Life is usually chaotic, but in we are used to a pattern in stories: the climax is the inevitable confrontation between protagonist and the antagonist. We know the climax is coming because other options are closed off.

When your ending “comes out of nowhere”, there were still other options the characters could explore. While rushing headlong at the antagonist might make for an exciting scene, most people prefer an easier non-confrontation than a harder, riskier encounter with their antagonist.

Or, you didn’t communicate how close the protagonist and antagonist were—having the evil wizard suddenly materialize in front of the warrior, and the warrior killing him with her magic sword, without any set up isn’t satisfying.

How to fix it: In Part 1, I said that as the main character tries to make things better, things get worse. But in short fiction, limit the number of things they can try. As the end looms, signal to the reader that the main character has one—and only one—last shot:

The main character assassin’s friend calls to say the target is boarding a train to leave the city

The crush is driving to the ex’s house for that weekend, and the main character needs to race to get there first

The helicopter arrives to take the strike team on their mission

Motion, especially toward something, is a great way to signal a coming climax.

Another way to signal the climax is to come out and say it. Have your characters discuss their plan to get what they want. Nothing signals the coming climax like someone saying: “We either do this, or we die.” The plan can (and should) fall apart, but it tells the reader that the end of the story is coming.

We also need to understand how the antagonist operates. If the antagonist doesn’t get its own scenes, at least explain its rules so when the confrontation happens we understand how.

“Ending took forever”

What they are really saying: This is opposite of what’s above when you didn’t signal we were heading into the inevitable confrontation. Instead, you signaled that we were heading into the climax too early. The climax, in general, is the last 1/4 of your story. That’s not a hard rule, but you should spend more time setting up how we get to the climax than in the actual climax. Enter it too early and readers are waiting (and waiting (and waiting)) to see who will win and how.

How to fix it: Using the examples above on how to signal we are transitioning into the story’s climax, go back and see how early or late in the story you give this signal. You might not even mean to set up the climax, but the reader thinks you did.

A common mistake that makes the ending seem to go on forever is raising the stakes in the climax. In longer works, you might be able to have one more reveal for raising the stakes, but in short fiction raise the stakes in the second act, but as we head into the final confrontation, we know what’s on the line. The end of the story is to wrap things up, not introduce new ideas.

For example, let’s say the convenience store manager from my earlier post is leading a group through the airport (the motion I mentioned above) to a waiting plane during a zombie attack. The stakes might be not just the survival of the group, but her own identity since earlier in her life as an army lieutenant she had failed to save her squad. If you suddenly introduce that one of the group knows how to stop the zombie apocalypse, it changes the story. Characters have to react and change as a result of this revelation, stretching things out. It might be only 100 more words, but it will seem longer. Lose that momentum and you lose the reader.

If you have story-changing reveals that appear in the climax, can you move them earlier in the story and make the middle more exciting?

The other aspect of this is after the climax. Short stories might not have enough room for denouement, but some can. Poorly done denouement, where things aren’t wrapped up or settled quickly, drags. It begs the question from readers of where are you taking them. When your main character wins over their crush, how does their life change? Tell us that and end the story. Page and pages describing dates and romance are events, not story.

“It just kinda stopped… there wasn’t an ending”

What they are really saying: This is a combination of the two items above. There were no signals that the story was coming to an end, and nothing is resolved.

How to fix it: Take the above advice into consideration.

But also, make it clear what’s on the line if the main character fails. Just as I said to not raise the stakes in the climax, we must know the stakes going into the climax. Otherwise we don’t know what all of the conflict is for.

For your main character assassin, why is it important to fulfill the contract? Money is not enough. Make it so we learn the master assassin (the target) has a contract for the main character’s family. For your character trying to ask out their crush, maybe they know that the crush wasn’t really happy with their ex, but the crush is lonely, so the main character is also helping the crush by saving them from a bad relationship.

And lastly, go back to the idea of the main character wanting something. Did they get it at the end of the story? If you begin a story with a man in jail for a crime he didn’t commit and he’s desperate to prove his innocence, but it ends with him killing the abusive gang leader, you didn’t finish your story.

In other words, your story will introduce some ideas and will-they-won’t-they questions. Make sure these are wrapped up.

Advertisements

December 8, 2017

How to understand what reader feedback *really* means (1/2) – Beginnings and middles

On November 21, I gave a short story writing workshop with Lydia Peever to the Ottawa Independent Writers. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to cover everything we wanted.

One of the things I wanted to discuss was how to translate feedback you might get from readers or editors into ways to identify problems with your story. In other words, what they really mean and what can you do about it.

This is the first part of a two-part post covering the beginning and middle of a story. I’ll post more about endings a little later.

“It started slow…”

What they are really saying: They don’t know what the character is after, or the character doesn’t do anything about getting that thing.

We are invested in stories through characters. And in stories, characters want something. The will-they-won’t-they of what they want propels the story:

Fall in love

Find treasure

Defeat the monster

Find the killer

That desire for something—and the drive to get it—is very human, and what readers identify with.

A character simply going about their day—without some desire for something—isn’t interesting. Nor is a character who wants something, but does nothing about it.

How to fix it: As Kurt Vonnegut said: “Make your characters want something right away even if it’s only a glass of water.” That initial will-they-won’t-they question, even for something minor, draws in the reader.

In longer works, what they initially want might not be the major driver of the story, but in short fiction try to introduce what the character is after as early as you can. This signals what kind of story follows: romance, horror, mystery. If you can’t introduce this main idea, then make the character want something minor from page one:

Go to bed

Take the dog for a walk

Answer a ringing phone

And once they do that, have that lead to some other want:

In bed ► Find what that strange sound in the house is

Walking the dog ► Who is that odd person standing on the corner

Answer the phone ► Who is the weird voice on the other end

The next step is to have the character taking action to get it. They might not succeed, but someone longing to go on a date with-so-and-so without doing something about it, or constantly running from the monster without figuring out how to defeat it, or wanting to go to a good school without doing the schoolwork, is just annoying.

“It didn’t grab me”

What they are really saying: This might be the same as starting slow, but hopefully a slow story picks up steam. This comment is worse. It means you didn’t communicate what was on the line if the character failed, or they didn’t care if the character failed.

What’s on the line, or stakes, is what makes the will-they-won’t-they question so compelling. But we have to care about the characters and their success or failure.

How to fix it: Character development is its own beast, but a simple thing to do is ask yourself why we should care about your main character. What do we identify with? What do we admire? We all love underdog stories, so what deficit is your character starting from that they must overcome?

Also, extend the stakes beyond the character. In horror, not defeating the monster might mean the main character dies, but the stakes can be increased—and draw the reader in deeper—if it also means the monster will move on from the farmhouse and destroy the town. In romance, the cheerleader turning down the chess club president for a date is not just disappointing, but might discourage all the chess club geeks from believing they are worthy of love.

“Not sure when the story started”

What they are really saying: It wasn’t clear when we left the status quo and entered the unknown. Terms for this include crossing the threshold, call to adventure, the first disaster, the inciting incident, or entering Act Two. (If you know your story structure, you’ll know these are different things. But we’re talking short stories here, so sometimes they are jammed together.)

The first part of a story is set up: where are we, when are we, what’s going on in this world, and who is our protagonist? Often this is a static situation—the status quo. Every day for your character is essentially the same.

Then, there is some event that disrupts the status quo and sets in motion all other events that follow in the story. This disruption usually comes from something outside the main character—a friend comes in from out of town, aliens invade, someone moves in next door. How your main character handles that disruption is essentially your story.

How to fix it: In longer works, you can take your time to establish the status quo. There are plenty of novels where not a lot happens in the first few chapters… and then suddenly we’re caught up in a whirlwind of adventure!

In short fiction, you might begin with set up or begin at that change in the status quo and then layer in backstory. Either way, you have to show the reader that something is new or different for the characters. This has two steps: some change from an outside source and the character’s reaction.

Outside sources could be:

A roadside convenience store is suddenly flooded with motorists fleeing some disaster in the city

A sergeant assigns a police detective a new case

A production company offers a famous daredevil a new challenge

These may be normal events for your character, but it signals to the reader that here is something new in their world. How the character reacts also helps to establish that we are leaving behind the status quo and entering something new, especially if the character isn’t able to initially handle this new situation:

The convenience store’s manager, usually tough and decisive, is overwhelmed in the chaos

The detective, by-the-book and methodical, can’t make any progress on the case

The daredevil, now in his 40s, realizes he doesn’t think he’s capable of the job

All of these engage the reader and promise them what the story will be about.

“The middle drags”

What they are really saying: Things happen, but it’s not building toward anything.

In the classic Three Act Structure, Act Two should have lots of action, rising stakes, twist and turns. Often, it can be the hardest to write, especially for short stories. You might have a great beginning and fabulous end, but you find you’re just moving characters around in the middle in order to connect beginning and end. Or the middle might be great battle scenes, witty banter or an exciting chase, but in the end nothing changes—the stakes are the same, your character hasn’t learned anything, and they want the same thing as the beginning of the story. That is, you can take a lot out and not lose much.

How to fix it: Once your main character crosses the threshold and the real story starts, have them fail. They proactively try to get what they want, but they are outside their comfort zone—they would succeed in the status quo, but we have left that behind. This might put what they want further away, signal their location to the enemy, or embarrass them in front of their love interest. These changes increase tension in your story and draw the reader in. It forces the question “What happens now?”

You should also increase the stakes. Don’t leave them the same as the beginning of the story. Make things worse for what can happen if the character fails:

Your main character is an assassin with a contract. Unable to kill their target, they learn their target is actually a master assassin.

Your main character is trying to find the courage to ask out their crush. When your character is about to ask, the crush and their ex talk about taking a week-long trip together to try to reconcile.

There’s been a last-minute replacement on a strike team that is inexperienced and puts the mission at risk. Then the timetable for the mission is moved up to tomorrow.

Rather than giving up, your main character should push forward. While the “What happens now?” question is plot, how your main character reacts is character development. They learn new things and act in new ways to be successful. They don’t have to be someone completely new, but understand that how they were at the beginning of the story didn’t get them to success. So while your main character may be reactionary at first, eventually you can have them be more proactive and beginning to take control. They are proactive because they know what they want, are working to get it—two things we should have in the beginning—and now might have a chance of success.

Lastly, the reason the story seems to drag is it’s clear you the author are moving things around rather than circumstances forcing characters to react. And as characters react, they affect other characters, forcing them to react. Character-driven action is much more interesting than you the author dropping in things to move them around.

How to understand what reader feedback *really* means (1/2)

On November 21, I gave a short story writing workshop with Lydia Peever to the Ottawa Independent Writers. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to cover everything we wanted.

One of the things I wanted to discuss was how to translate feedback you might get from readers or editors into ways to identify problems with your story. In other words, what they really mean and what can you do about it.

This is the first part of a two-part post covering the beginning and middle of a story. I’ll post more about endings a little later.

“It started slow…”

What they are really saying: They don’t know what the character is after, or the character doesn’t do anything about getting that thing.

We are invested in stories through characters. And in stories, characters want something. The will-they-won’t-they of what they want propels the story:

Fall in love

Find treasure

Defeat the monster

Find the killer

That desire for something—and the drive to get it—is very human, and what readers identify with.

A character simply going about their day—without some desire for something—isn’t interesting. Nor is a character who wants something, but does nothing about it.

How to fix it: As Kurt Vonnegut said: “Make your characters want something right away even if it’s only a glass of water.” That initial will-they-won’t-they question, even for something minor, draws in the reader.

In longer works, what they initially want might not be the major driver of the story, but in short fiction try to introduce what the character is after as early as you can. This signals what kind of story follows: romance, horror, mystery. If you can’t introduce this main idea, then make the character want something minor from page one:

Go to bed

Take the dog for a walk

Answer a ringing phone

And once they do that, have that lead to some other want:

In bed ► Find what that strange sound in the house is

Walking the dog ► Who is that odd person standing on the corner

Answer the phone ► Who is the weird voice on the other end

The next step is to have the character taking action to get it. They might not succeed, but someone longing to go on a date with-so-and-so without doing something about it, or constantly running from the monster without figuring out how to defeat it, or wanting to go to a good school without doing the schoolwork, is just annoying.

“It didn’t grab me”

What they are really saying: This might be the same as starting slow, but hopefully a slow story picks up steam. This comment is worse. It means you didn’t communicate what was on the line if the character failed, or they didn’t care if the character failed.

What’s on the line, or stakes, is what makes the will-they-won’t-they question so compelling. But we have to care about the characters and their success or failure.

How to fix it: Character development is its own beast, but a simple thing to do is ask yourself why we should care about your main character. What do we identify with? What do we admire? We all love underdog stories, so what deficit is your character starting from that they must overcome?

Also, extend the stakes beyond the character. In horror, not defeating the monster might mean the main character dies, but the stakes can be increased—and draw the reader in deeper—if it also means the monster will move on from the farmhouse and destroy the town. In romance, the cheerleader turning down the chess club president for a date is not just disappointing, but might discourage all the chess club geeks from believing they are worthy of love.

“Not sure when the story started”

What they are really saying: It wasn’t clear when we left the status quo and entered the unknown. Terms for this include crossing the threshold, call to adventure, the first disaster, the inciting incident, or entering Act Two. (If you know your story structure, you’ll know these are different things. But we’re talking short stories here, so sometimes they are jammed together.)

The first part of a story is set up: where are we, when are we, what’s going on in this world, and who is our protagonist? Often this is a static situation—the status quo. Every day for your character is essentially the same.

Then, there is some event that disrupts the status quo and sets in motion all other events that follow in the story. This disruption usually comes from something outside the main character—a friend comes in from out of town, aliens invade, someone moves in next door. How your main character handles that disruption is essentially your story.

How to fix it: In longer works, you can take your time to establish the status quo. There are plenty of novels where not a lot happens in the first few chapters… and then suddenly we’re caught up in a whirlwind of adventure!

In short fiction, you might begin with set up or begin at that change in the status quo and then layer in backstory. Either way, you have to show the reader that something is new or different for the characters. This has two steps: some change from an outside source and the character’s reaction.

Outside sources could be:

A roadside convenience store is suddenly flooded with motorists fleeing some disaster in the city

A sergeant assigns a police detective a new case

A production company offers a famous daredevil a new challenge

These may be normal events for your character, but it signals to the reader that here is something new in their world. How the character reacts also helps to establish that we are leaving behind the status quo and entering something new, especially if the character isn’t able to initially handle this new situation:

The convenience store’s manager, usually tough and decisive, is overwhelmed in the chaos

The detective, by-the-book and methodical, can’t make any progress on the case

The daredevil, now in his 40s, realizes he doesn’t think he’s capable of the job

All of these engage the reader and promise them what the story will be about.

“The middle drags”

What they are really saying: Things happen, but it’s not building toward anything.

In the classic Three Act Structure, Act Two should have lots of action, rising stakes, twist and turns. Often, it can be the hardest to write, especially for short stories. You might have a great beginning and fabulous end, but you find you’re just moving characters around in the middle in order to connect beginning and end. Or the middle might be great battle scenes, witty banter or an exciting chase, but in the end nothing changes—the stakes are the same, your character hasn’t learned anything, and they want the same thing as the beginning of the story. That is, you can take a lot out and not lose much.

How to fix it: Once your main character crosses the threshold and the real story starts, have them fail. They proactively try to get what they want, but they are outside their comfort zone—they would succeed in the status quo, but we have left that behind. This might put what they want further away, signal their location to the enemy, or embarrass them in front of their love interest. These changes increase tension in your story and draw the reader in. It forces the question “What happens now?”

You should also increase the stakes. Don’t leave them the same as the beginning of the story. Make things worse for what can happen if the character fails:

Your main character is an assassin with a contract. Unable to kill their target, they learn their target is actually a master assassin.

Your main character is trying to find the courage to ask out their crush. When your character is about to ask, the crush and their ex talk about taking a week-long trip together to try to reconcile.

There’s been a last-minute replacement on a strike team that is inexperienced and puts the mission at risk. Then the timetable for the mission is moved up to tomorrow.

Rather than giving up, your main character should push forward. While the “What happens now?” question is plot, how your main character reacts is character development. They learn new things and act in new ways to be successful. They don’t have to be someone completely new, but understand that how they were at the beginning of the story didn’t get them to success. So while your main character may be reactionary at first, eventually you can have them be more proactive and beginning to take control. They are proactive because they know what they want, are working to get it—two things we should have in the beginning—and now might have a chance of success.

Lastly, the reason the story seems to drag is it’s clear you the author are moving things around rather than circumstances forcing characters to react. And as characters react, they affect other characters, forcing them to react. Character-driven action is much more interesting than you the author dropping in things to move them around.

Advertisements