G.D. Falksen's Blog, page 994

October 25, 2013

The following article, originally published in 2009, was the...

The following article, originally published in 2009, was the first blog piece to discuss and explore the idea of multicultural steampunk. It was in many ways a culmination and summary of a number of earlier articles on multicultural steampunk that I had written for the Steamfashion community on Livejournal, and its main purpose was to help demonstrate the complexity and diversity inherent in steampunk. Following the article’s publication, I was surprised and honored to learn that I had inspired the formation of several different blogs dedicated to multicultural steampunk. I had never expected one article of mine to have had such a tremendous effect on people, but I am so happy that it did.

Multiculturalism in Steampunk

“The world is not enough…but it is such a perfect place to start" by G.D Falksen, originally published on October 5, 2009 here.

While steampunk is most easily summarized as “Victorian science fiction,” it is important to remember that this terminology is used to reference a period of time rather than a specific culture. While it is sometimes mistakenly assumed that Europe or the West must inevitably be the dominant subject of steampunk fiction, this could not be further from the truth. In fact, the blending of science fiction and alternate history found in steampunk make it possible to take the existing complexity and diversity of the 19th century world and bring non-European discourse into an even greater form.

Europe receives a great deal of attention in steampunk for understandable reasons. The Industrial Revolution began in England and spread to the Continent sooner than to most other parts of the world. However, many areas in Europe still wrestled with aspects of modernization: in Russia, the archaic institution of serfdom remained in place until the second half of the century, while “Germany” did not exist as a nation until the early 1870s.

The Americas are an easy place to move to after departing the European side of steampunk. The United States was second only to the British in terms of industrialization, and during the 19th century many of the other American colonies achieved independence from Europe. These represented new nations with unique cultures drawn from both native and European traditions. Haiti deserves a special mention as an independent republic ruled not by the descendents of Europeans but by the descendents of African slaves who had fought a revolution for both freedom and independence.

When discussing the Americas, one cannot forget the continents’ native peoples. While a number of Native American groups had already been subdued by the European colonies, the 19th century saw numerous conflicts as the new American nations sought to expand further into native territory. Even after absorption the dialogue continued, as native peoples adapted to their situation. In many cases this involved a fusion of cultures and goods. Adaptation is a key theme among the Native Americans, many of whom adapted to European-instigated changes better than the Europeans themselves, including in the area of technology. After the Civil War, the gun trade provided Native Americans in the West with repeating rifles, making them one of the most advanced cavalry forces in the world; at the same time, the United States restricted its cavalry to single-shot carbines while the Europeans held firm to their archaic obsession with sword and lance.

Africa is often overlooked when considering steampunk, which is a shame given that it was not colonized in force by Europeans until the end of the 19th century. For much of this period Africa was ruled by Africans, not only by local tribes but also by large and highly organized kingdoms and empires. Historically, the empires of Africa were cosmopolitan and possessed complex governmental systems, pre-industrial manufacturing and militaries that used metalwork, cavalry and firearms. Introduce pre-colonial industrialization and one has the perfect starting point for indigenous African steampunk.

Asia provides one of the finest examples of non-European “real world” steampunk, in the form of Japan. Historically, Japan modernized and industrialized with such effectiveness that it was able to supplant China as the dominant power in East Asia, then go on to defeat Russia (which at that time was a world superpower with eyes on Asian hegemony), and finally become an international power in its own right. Introduce the freedom of fiction provided by steampunk, and other nations follow. In China, the failure to modernize was in part caused by the Dowager Empress Cixi, who was reluctant to engage in full-scale reform. Remove her as a stumbling block to industrialization, and Chinese steampunk is free to blossom.

The so-called Great Game between Russia and Britain for control of Central Asia can be seen as a 19th century anticipation of the Cold War, and during this struggle the Asians themselves had significant roles to play. Many local rulers saw the competition as a means of pitting one European against the other in exchange for wealth, technology and power, and many times these attempts were successful. Afghanistan, Bokhara, the newly formed nation of Kashgaria, all engaged with the British and Russians as active participants. Even non-Europeans from outside of Central Asia were involved in the struggle: Indian explorers disguised as Buddhist pilgrims were employed by the British as spies and scouts in the region.

The Indian subcontinent is especially viable for explorations into steampunk in part because of its cosmopolitan nature and in part because of its position as a key portion of the British Empire. Its role as a British colony makes it a natural recipient of Europeanized steampunk, but this should not undermine India’s own unique voice in the genre. Remove the British from the equation (perhaps by a dramatically more successful Indian Rebellion in 1857) and a wholly indigenous adaptation of technology becomes possible. However, it must be remembered that India has a long history of absorbing and blending diverse ideas, belief systems and sciences, and there is no reason to think that it would not give a unique look and feel to its steampunk even while subjected to colonial rule.

Due to its position as a major crossroads of trade and travel, Southeast Asia possesses an incredible degree of diversity that makes it difficult to categorize. During the 19th century parts of Southeast Asia had already been colonized by Europeans, while others remained independent and were colonized as the century wore on. Others, such as the Philippines, fought wars for independence with varying success. Throughout its history, Southeast Asia has absorbed and combined diverse ideas, cultures and belief systems far more effectively and harmoniously than in other parts of the world, and as with India it is likely that steampunk in a colonized Southeast Asia would still develop a unique feel. At the same time, steampunk offers the possibility of industrialized pre-colonial nations in Southeast Asia, or even earlier and more successful revolutions set in the 19th century.

In the Middle East, the aging powers of Persia and the Ottoman Empire were still powerful enough to enter diplomatic consideration, and one wonders if the restructuring and industrialization of a steampunk influence might well have saved them. Alternatively, a steampunk world could see the Arab Revolt of the First World War occurring sooner or with greater success. The idea of a united and independent Arabia in the 19th century with cities and oases united by railroads or airships is undeniably steampunk.

It is especially pleasing to know that the wealth of diversity available to steampunk fiction has successfully translated into the steampunk subculture. Not only are people comfortable with exploring the diverse sources of fashion and aesthetic inspiration available to them, but the trend’s membership is diverse as well. While many subcultures find themselves divided upon ethnic, social or economic lines, steampunk has found adherents among countless different people of not only European but also Asian, African, Middle Eastern and Native American descent. Its ranks include members of the working class, the middle class, academia and even the independently wealthy, all of whom are united by a common love of the 19th century aesthetic and the steampunk genre.

If you are a writer, an artist or a costumer looking for sources of inspiration for non-European steampunk, consider these all viable starting points. However, the world is a big place and it would be impossible to provide a totally exhaustive list in so short a space. Look through the wealth of cultural diversity present in the 19th century and see what draws your attention. Add science fiction and you’re good to go.

For additional references and sources of inspiration, check the old G.D. Falksen history tag over on Steamfashion.

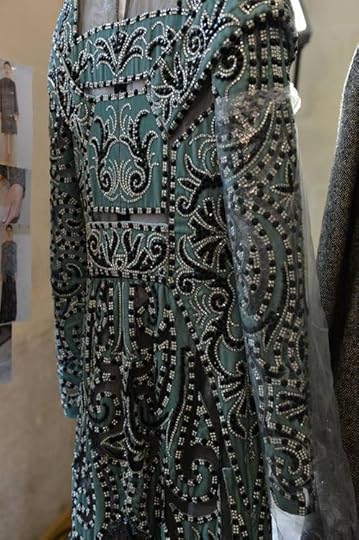

jMagic Details by VALENTINO F/W ‘13/14 Haute Couture Exquisite...

j

Magic Details by VALENTINO F/W ‘13/14 Haute Couture

Exquisite details, such as delicate feathers, precious endless beadings, golden thread embroideries or print intarsia, are what make gowns unique, ageless works of art

Up Close: Ball Gown c.1875 (X)

Jacket

1895

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Jacket

1895

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

What would you be?

October 24, 2013

Gold Pin with Lynx Head

Hellenistic Greek, found in Ukraine

The...

Gold Pin with Lynx Head

Hellenistic Greek, found in Ukraine

The top of the gold pin is a finely modeled lynx head. A small molding on the shaft of the pin keeps the garnet bead and conical collar from slipping off. One setting with a tear-drop garnet is firmly fixed in the lynx’s mouth by a pin, the extremity of which is looped. Chained to the loop is a second tear-drop garnet.

Source: The Walters Art Museum