Elizabeth A. Havey's Blog, page 6

January 2, 2022

HAPPY NEW YEAR, 2022

Today, as a New Year begins, I want to thank all of you for reading my posts, for commenting and for helping me continue to be the writer I have always been. I’ve shared a lot of my life with you, my dreams and sorrows, anger and joy. And you’ve been there to read and comment.

Life is better when the thoughts that build inside of us can be shared with others. Wishing you a healthy New Year this amazing 2022. Blessings on all of you and may your lives be rich in ideas, beliefs and love. Beth

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterestDecember 26, 2021

It’s That Time of Year to Be Thankful and Remember

If Christmas lights a spark for my grandchildren, inspires them to dream of the future and desire the shiny-new and surprising—for me, Christmas is the vehicle of memory. As soon as I open the first carton that stores my ornaments and Christmas decorations, a door to the past opens. Memories explode from the carton that holds the stockings with my children’s names, the Jack-in-the-Box that goes under the tree, and of course, the ornaments. I’ll anticipate unwrapping the fragile blue doll given to me when I was pregnant, the ballet slippers celebrating Christie’s love of dance, the tiny piano with Carrie’s name, and the many ornaments welcoming our son, now taller than most Christmas trees.

If Christmas lights a spark for my grandchildren, inspires them to dream of the future and desire the shiny-new and surprising—for me, Christmas is the vehicle of memory. As soon as I open the first carton that stores my ornaments and Christmas decorations, a door to the past opens. Memories explode from the carton that holds the stockings with my children’s names, the Jack-in-the-Box that goes under the tree, and of course, the ornaments. I’ll anticipate unwrapping the fragile blue doll given to me when I was pregnant, the ballet slippers celebrating Christie’s love of dance, the tiny piano with Carrie’s name, and the many ornaments welcoming our son, now taller than most Christmas trees.This is the season of wonder, one that illuminates memory. A single ornament holds thoughts of the person who gifted it, the tree where it was displayed or possibly a full-blown picture of the living room that it graced in years past. Memories abound this time of year.

And though the season pulls us in many directions, we are making memories—an amazing and wonderful thing. When I find a quiet moment, I want to breathe in the scent of paperwhites, enjoy the sparkle of lights and ornaments and read Dylan Thomas’s A Child’s Christmas in Wales. I’m looking back but also making new memories. What will you do to capture the essence of these days, these moments? Wouldn’t it be amazing if all of us could once again capture elements of child-like eagerness? That would be a perfect gift.

Music certainly is part of the memories of Christmas. Do you have a song for the season that brings you joy or makes you cry when you hear it? If it’s a shining moment in your past, it’s probably a wonderful idea to share it again. And if you put up a real Christmas tree, there might be in your family as there is in mine, that family argument. I really wanted a Scotch Pine. No, you liked the Balsam, I remember!

Each event has the power to become a shining ornament on the family tree. Each event increases the gift of love in our families. Christmas or whatever you celebrate this time of year is about love and giving, the amazing experience of family, the celebration of times when we were close and enjoyed being together. I sincerely hope those experiences for all of you reading this.

Then when the season ends, the tree comes down, those reminders of the past are put away, we might notice a change in family members, especially children. Where before they were peering into the future, excited and bright-eyed, now we might notice they are slightly sad or mopey. We might ask why has the spark dimmed? We mumble to ourselves: We’ve had such a wonderful time, why these low moments?

It’s truly okay. Children, all of us, are forming memories. Young or old, we experience nostalgia, a feeling defined as pleasure and sadness, caused by remembering something from the past and wishing that you could experience it again. What a great thing, to honor our experience of Christmas by forming memories.

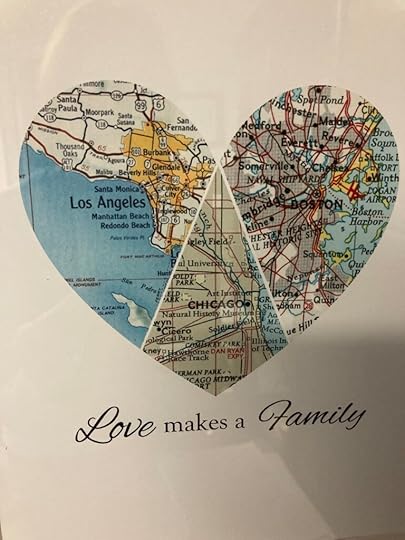

Each of us carries in our hearts hundreds of memories that help build our traditions. We preserve the gift of memories that are endlessly fervent, spiritual and uplifting. We form families that are vastly different, and how amazing and perfect that is. Ebenezer Scrooge said: “I will honor Christmas in my heart and try to keep it all the year.” Wishing you peace and love, Beth .

Thanks to Pinterest for the Art Work.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterestDecember 19, 2021

FIRES

My Aunt told us about a fire, speaking slowly to shake out the memory. I could see the row of newly built wooden houses, the smoke billowing while men struggled with hoses. She could see it too, the details stronger in each retelling, she having been a child, wrapped in a blanket, pushed in a stroller. My Aunt didn’t comment that it was wrong for her to see such destruction. But I knew. Now she feared fires.

All became quiet at the table as I focussed on the swirl of flower petals in the tablecloth, glad of the arrival of cheese and fruit, though fires flickered right there in the candles inches from my hands.

THE THINGS KIDS DO

When we were kids, we burned leaves in dusty piles in the driveway turnaround under our apple tree. We waited all week to do the raking, smell the fire, watch the smoke going up into the branches, the wind kicking the flames around. And we were kids doing this! There was a fire station on 95th Street, fire hydrants down the block. We had plastic fire hats when we ran around the yard with the garden hose, pretending. And there was that door on the furnace in our basement where you could watch the gas flames leap around, hear the motor humming heat slowly up through the registers.

Our house was grey frame, large front porch, scraggly lawn, western windows catching sunlight. It was a place of cut knees, birthday parties, fights with my brothers and my father’s death—a heart attack, he slumping over, dying in a red fabric chair that was still in our living room as I grew–my childhood fused in wood and plaster, mingling with the slope of the ceilings, the creak of floors, the air of that spiritual space.

ANNA

That was the time A nna came to clean for us. She came early, clumping up the back steps in shoes that never fit. I didn’t wonder about this, it was Anna—her clothes hung on her, and she always wore three black plastic bracelets that clicked together along her thin brown arm. She wore an an old stocking over her hair, her wrinkled face warm, brown eyes full of something like child’s mischief or secrets she couldn’t tell us. She moved furniture, swept stairs, burned the trash in the backyard, her body bowed to work, so that year after year she seemed to shrink while we grew.

Mother worked in the dining room typing insurance policies. When we came in from school she’d stop to ask what we wanted for a snack or to see our school papers. Eating bananas, cookies, we watched Anna working in the kitchen, spreading old newspapers over the newly washed floor. She’d smile at us, talk to us, tell us what good children we were. On rare occasions we heard stories about her own children, her face opening as she spoke. And Anna always brought us Chuckles, five pieces of sugar-coated candy, surely a gift she couldn’t afford. Did we remember to thank her?

As we grew, became more aware of the distance between us and Anna; we began to understand. Our father was dead; our mother typed insurance policies in our dining room to care for and protect us. But Anna was Black. Anna was poor. She did not have what we had.

THE PHONE CALL

Then one autumn our phone rang, a Friday. I heard my mother say “fire.” I always listened when my mother was on the phone, worrying someone would give her news that would hurt her. But fire. Where was this fire? Could I see it? My mother was saying: “Are the fire trucks there, is everyone out?” And then she was telling me to go and find Anna.

I don’t remember where I found her—arranging my mother’s perfume bottles on a mirrored tray, cleansing our bathtub, wandering back from the trash burner, her bent body preventing her from seeing the hunks of my mother’s carbon paper sailing around the yard like curling black birds.

I told Anna she had a phone call, and then ran ahead. I could only hover at the edge of her life, watch her take the phone from my mother there in the dining room, dusk pulling away all light, her small head shaking as she talked awkwardly into the phone.

When she hung up, she had to sit down. My mother brought her a glass of water, touched her shoulder, the room transformed, Anna’s head sinking lower and lower. I could picture her things burning up, things she had told us were in her house—the picture of Abraham Lincoln, a quilt my mother had given her along with dresses, linens, dishes—things we didn’t use any more. Things Anna always accepted.

A man was coming to pick Anna up. She thought he lived in her neighborhood. We stood around the dining room table waiting while Anna trembled. It got dark against the dining room windows, my brothers running to the front door when the bell sounded. Anna had to push her hand on the top of that table to get out of that chair.

Two white men stood on the front porch. I could see behind them a long white Cadillac, gleaming under the street light. I watched them take Anna down the front walk, opening that car door for her, a door so large it swung into the street. The car swallowed her. They drove away.

LATER THAT NIGHT…

But I was glad they were gone. I was the one to slam the front door against the cold air. I was always worried about my mother. She had argued with the men about Anna, raised her voice while Anna stood frail, alone on our porch. The men had said something like “everything is under control.” But nothing felt right. Our Anna between those two white men in their heavy winter coats, my mother talking, fatherless me cowering behind her, thinking those two men might come into our house and stay.

But they were gone. I didn’t have to watch Anna sitting at the table, not moving about like she always did. I must have thought Anna liked to be always shuffling around our house. I didn’t yet know the strong desire to sit after working all day. I didn’t understand about long walks to a bus carrying other people’s cast-off things while yearning for your own four walls. Then…

Later, we were in the kitchen making dinner, pulling the shades, holding the light inside for just the four of us—and the doorbell rang. A man on our porch, a Black man, saying that he had come for Anna. He had a little blue truck parked in our driveway.

I don’t think any of us ate much that night. Anna signed some paper in that white car and lost even more money than she lost in the fire. At least that’s what my mother told me, and I think she knew what really happened.

Anna came back to work a few weeks later. She looked the same. She probably brought us Chuckles. We asked her about the fire, but she just shook her head, smiled that secret smile. We had often asked her how old she was, but she didn’t answer, except once, telling us old enough to have family who had been slaves. And because she had once showed us, we asked her why she always carried a knife in her purse. She smiled, said we didn’t need to know. And then we just forgot, forgot it all, moved back into our child-world, unable to see what Anna could show us—what it really meant to survive, to live, to endure.

Anna had also worked for my grandmother. She cared for us and we for her in a pattern that was structured by the times. Later I realized my mother should have driven Anna home the night her house was on fire. But it was dark, my mother was a widow with three children, and Anna didn’t live in our neighborhood. And I certainly didn’t understand about other neighborhoods.

Safe and secure, we were frozen behind cultural boundaries and borders. And though I didn’t have a father, I did have a mother whose strength and love allowed me and my brothers to live a childhood that danger didn’t penetrate. Mom protected us, we fearing nothing in our time of innocence. Yes, we knew that people got sick and died, like our father, like our neighbor, Mr. Carl. It was natural for us to blot out things that made us fear losing another.

FINAL THOUGHTS…

Anna came to us, even when she really could not do a proper job, my mother wanting her to have work, dignity. But as Anna faded from our lives, we learned to take risks, to not hold on so tightly to a certain way of life. We saw there was room for sorrows and joy. Anna could have taught us many important lessons if we had been able to ask her, to break down barriers, talk openly of the lessons her courage and love were quietly teaching us.

But we were children, waiting for those hot summer nights when we ran through the dry grass, argued about whose peanut butter jar held the most fireflies. And waiting for winter, when dressed against the cold, we warmed our faces in the heat of fire, watching our six-foot evergreen, now dry and brittle, signal the brilliant end of our full and blessed Christmas.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterest

December 12, 2021

The Story of a Rug

My maternal grandfather, Peter Rausch, was in the rug business. He worked for a large commercial venture in Chicago, the department store Marshall Fields, his position that of selling oriental rugs.

But please note: by definition, oriental rugs are carpets hand knotted only in Asia. The countries of Iran, China, India, Russia, Turkey, Pakistan, Tibet and Nepal are some of the biggest exporters of oriental rugs. Persian rugs are also oriental rugs, but made only in Iran (formerly known as Persia). Currently, the term o riental rug is loosely used to describe a type of rug, one with delicate and intricate designs, one that is often made of deep red and blue yarns.

Grandfather Peter was selling the real thing, heavy, hand-made rugs which he actually carried with him in a large trunk, so as to display to his buyers the weave, the colors and the expert workmanship. He often traveled by train, loading up his trunk to stop in smaller stores across the Midwest, whose buyers and owners were eager for these expensive rugs from Marshall Fields.

THE HARD LIFE OF A SALESMAN

I didn’t really know my grandfather. He died way before my grandmother who lived into her nineties. Arthur Miller published his stage-play, Death of a Salesman around the time my grandfather died.

The play addresses the struggles that men and woman faced as society was rapidly changing, eliminating their jobs or radically altering them. The main character, Willy Loman, (a play on words, a man becoming a low-man) relies on his singular vision of the American dream–traveling the country with his display case, making big sales, hoping to return home a hero. The play is stunning, it being Miller’s comment on societal changes, his focussing on the traveling salesman who is slowly being replaced by an industrial and advancing society. Death of a Salesman premiered in 1949. My grandfather died in 1952. I wish I could have discussed the play with him, garnered what he thought about it. He might have said that Miller over-dramtized Willy’s situation–but that was purposeful. Miller was making a statement with lines like: “The jungle is dark, but full of diamonds”…“A small man can be just as exhausted as a great man.” “You can’t eat the orange and throw the peel away – a man is not a piece of fruit.”

THE RED AND BLUE RUG

I don’t know if my grandfather ever told a specific story about the red and blue rug that graced the wooden living room floor in my grandmother’s house. Later it graced my aunts smaller home and is now gracing my brother’s living room. (see photo). I don’t know if my grandmother raised her hands to her face (her familiar gesture) in gratitude and surprise when my grandfather brought it through their front door.

But I was there, years later, when my Aunt Lucia had to leave her home for a care center, and thus had to say good bye to her piano and that rug. Lucia sat by me at the piano, gently touching the ivory keys. My brother had found a mover, a guy who refitted an old bus to hold the piano, the rug and boxes of china and silver–all to be shipped to California, where my brother lives. That night we said good- bye to these cherished items as we watched the bus drive away.

Weeks went by, my brother back in LA, my mother calling him constantly, asking about the bus that was filled with the piano, the rug and family heirlooms. Finally, my brother had to hire a detective, suss out where the mover lived and if he had sold our family goods, pocketed the money, cheated us out of more than physical goods, but also previous memories. The detective was a bit ill at ease when he discovered there had been some other questionable transactions this mover guy had been involved with. But he found all our goods in the mover’s barn, my brother instructing him that he didn’t want to prosecute the guy, he just wanted the piano back and all our belongings. My brother then hired a major moving company to pick up the items and drive them safely to Los Angeles. The detective oversaw the recovery of the items to make sure that every thing was there, everything was recovered. No one could make this story up. Not even Willy Loman.

FINAL THOUGHTS

I do wonder what my grandfather would have thought about all of this. Now his traveling rug has been refurbished and provides comfort and memories to my brother, his wife and anyone who visits, anyone who cares to bend down and touch this beauty, remember the history.

Below is a photo of my grandfather’s trunk. He had arthritis as he aged, rather expected for a tall man who lugged this case, who was on his feet most of the working day. But there was the day, when he was tired, his feet not cooperating and he fell, fell in his living room, went down like a large tree, only to have a soft landing–the rug, the red and blue rug in his living room.

Thanks for reading.

PS On a cruise to Italy, Greece, Mediterranean islands, we stopped in Turkey. After seeing religious and historical ruins in Ephesus, we were taken to a store where true oriental rugs were being made and purchased. I found one I loved, brought it back in a suitcase! While watching a young woman who was demonstrating the hard work that goes into making oriental rugs, I asked the store owner if men ever do the weaving. He assured me that NO, THEY WATCH FOOTBALL.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterestDecember 5, 2021

About Writing a Novel (taken from the list of Alexander Chee)

Alexander Chee is the bestselling author of the novels Edinburgh, The Queen of the Night, and the essay collection How To Write An Autobiographical Novel. The following post is taken from his work 100 THINGS ABOUT WRITING A NOVEL. Since I have written three novels (all yet to be published) and since I know many of my readers are also writers, I am sharing some of the intelligent and humorous ideas that Chee has included in his list. This list is for writers, but readers will love it too. Thanks for reading…(and please note: the numbers in my post do not necessarily coincide with his original numbers.)

A novel, like all written things, is a piece of music, the language demanding you make a sound as you read it. Writing one, then, is like remembering a song you’ve never heard before.I have written novels on subways, missing stops, as people do when reading them.They can begin with the implications of a situation. A person who is like this in a place that is like this, an integer set into the heart of an equation and new values, everywhere.The person and the situation typically arrive together. I am standing somewhere and watch as both appear, move toward each other, and transform.Or like having imaginary friends that are the length of city blocks.You write the novel because you have to write, in the end. You do it because it is easier to do than not to do. After all, a dragon has come all this way and it knows your name.I do not answer the question What is the novel about? or How is the writing going? It is because my sense of a novel changes in the same way my knowledge of someone changes.Novels are delicate when they are being written, if also voracious. They move around my rooms, stripping half-finished poems of their lines, stealing ideas from unfinished essays, diaries, letters, and sometimes each other. Sometimes, by the time I get to them, one has taken a huge bite out of the other.Revision means turning something like laundry into something like Christmas.This is because the first draft is like scaffolding; often it must be torn down to uncover the things being built underneath. Which is to say, some second drafts, when they emerge, have very little visible relation to the first.The novel coming not from the mind but the heart, which is why it cannot fit in your head. Why, when you hear it, it seems to be singing from somewhere just out of your sight, always.Everyone has a novel in them, people like to say. They smile when they say it, as if the novel is special precisely because everyone has at least one. Think of a conveyor belt of infant souls passing down from heaven, rows of tired angels pausing to slip a paperback into their innocent, wordless hearts.What if the novel in you is one you yourself would never read? A beach novel, a blockbuster, a long windy character-driven literary drama that ends sadly? What if the one novel in you is the opposite of your idea of yourself?All the while, we know that in some cultures we would be revered as gods. In others, put to death.Novels do not take orders well, if at all. They are not soldiers, usually, or waiters. They do badly at housework and will not clean silver.For most, novels are accidents at their start. Writers lining the streets of the imagination, hoping to get struck and dragged, taken far away. We crawl from under the car at the destination and sneak away with our prize.The novel is a letter from the novel to the reader, and dictated to the writer by the writer.I just need to get a drink, I’ll be right back, the novel says. Do you want anything?Days later the novel returns. I wasn’t with anyone else, the novel says. There’s only you, the novel adds, even as the writer fears it has taken up with others. Imaging pages across the other desks of the neighborhood.There’s only you, the novel says again. The novel is already at the door, waiting, but for a little. It is the lover again, wanting again for you to know everything.Thanks to Alexander Chee, department of English and Creative Writing, Dartmouth

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterestNovember 28, 2021

December: Voices, Memories, and Giving

“It’s coming on Christmas.”

The voice may be tenor or soprano. The music may be folk, modern or classical. Whatever your choice, it now begins—Christmas music reemerges as we celebrate the season in sound. We hum, sing along. My husband and I move from Diana Krall and Bill Evans, to the Robert Shaw Choral, Vince Guaraldi’s Charlie Brown Christmas, James Taylor’s Christmas songs. Everywhere, there’s wonderful variety, music becoming the focus of family get-togethers, school celebrations and church events. Music is tradition. Music is memory.REPETITION AND REMEMBRANCE or “GET UP ON YOUR FEET”

What song do you look forward to singing? Do you play old records or click on Spotify? Some of you might be part of a church choir—but with Covid, you might be forced to abandon practices. But you can always sing to your Christmas tree, remember the songs that make you joyful for your beliefs.

Music captivated my younger brother in his teens, became his lifelong career and passion, so at Christmas, his Christmas Dreams collection is a favorite. He and my son will grab guitars, play, sing, fill the house with sounds of the season—and they’re always open to requests–grandchildren, cousins, everyone dancing. Be joyful, move your body—that’s all that’s required. Got a new move? Share it, for the holidays are always about health and new life, about blotting out the darkness that pervaded much of the world, about lighting candles, fires, and gathering people together to share food, drink and love. ( But honor your host regarding what you can bring to a celebration and do make sure you are vaccinated.)

DECEMBER: A TIME FOR EVERYONE

The very existence of the Christmas season will always be connected to new life, the birth of Jesus Christ. It is also about memories, the cranberry bread you make every year. The lights you hang on shrubbery, trees and doorways to light up your surrounding world. The warm room, maybe a fireplace burning and always a hug or words of caring for those who come through your door. Just think: even though Australia and countries on the other side of the equator are unpacking their summer clothes—it’s still “coming on Christmas.”

And yet there are shadows that even a brightly lit world cannot dispel. Maybe this is your first Christmas without a parent, a spouse, your closest friend. This is a Christmas where your time will be spent visiting your son in rehab or remembering to take medication for a recently developed condition. Some of you will travel to rejoice with family and friends, or to mourn with them. But we humans keep going, healthy, struggling, joyful or sorrowful, we keep on…

MORE VOICES…

Chris Erskine, in his column a few years back, reminded his daughter: “Everybody is someone.” That statement is always true, but during this season when emotions are heightened, memories can hang over one’s day like a dark cloud–instead of mistletoe. It’s best to remember to care for or smile at those you meet. And you could ask yourself, do I really need “another ornament” for the overloaded tree? I know I don’t, remembering that my mailbox has been full of organizations asking for help. Write that check, mail it today.

So whatever your December brings you, I hope you will experience contentedness, the desire to reach out to others. After all, the season is only beginning, plenty of time to be grateful, to make Santa Claus come alive and for a child. Thanks for reading.Artwork: thanks to Nancy Haley nancyhaleyfineart.com

This is an older post that has been edited.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterestNovember 21, 2021

THE STORY OF ONE PREGNANT PATIENT & THE APGAR SCORE

Virginia Apgar

Writer and physician Atul Gawande, reminds us in his book, BETTER, that much of modern medicine did not just happen—it came to be through trial and error, through the deaths of others, the mistakes and triumphs that IS the history of medicine. In BETTER, a surgeon’s notes on performance, we meet Elizabeth Rourke in the chapter, THE SCORE.

OUR PREGNANT PATIENT

Rourke is forty-one weeks pregnant, having contractions. She’s an internist, on staff at Mass General. Her contractions are 7 minutes part. She reports this to her obstetrician at 8:30 am. She is told not to go to the hospital until her contractions are 5 minutes apart. Standard protocol. (this book was published in 2007). In medical school, Rourke has seen fifty births, delivered 4, and watched one in a hospital parking lot. It was winter, the baby was blue, crying. They covered the infant, raced back into the hospital. With that memory, Rourke finished packing her bag and her husband drives her to the hospital.

SOME HISTORY

Gawande then relates some history of pregnancy and birth that has been recorded. He writes of 21-year-old Princess Charlotte of Wales, in 1817, four days in labor, struggling to deliver a nine-pound boy in a sideways position, his head too large for her pelvis. When he finally emerges, he is stillborn. Charlotte dies six hours later from hemorrhagic shock. Gawande relates that her physician was reviled for not using forceps. In remorse for her death, he shot himself.

Gawande relates other statistical history of births—that in 1933, the New York Academy of Medicine published a shocking study of 2,041 maternal deaths in childbirth in New York City. At least two-thirds of those deaths investigators found to be preventable, that many physicians simply did not know what they were doing. They missed signs, symptoms, incorrectly used forceps and spread infection. Midwives did better.

UPDATE ON OUR PATIENT, ROURKE

Her pain has increased, thinks she must be 7-8 centimeters. She is at 2. Her labor has stalled. Then at 2:43 AM she is at four centimeters. It’s been twenty-two hours. They give Rourke an epidural. This is not a simple procedure. Gawande goes through the steps, explaining the risks, one being the mother’s heart rate dropping and the necessity for a bolus of fluid injections and ephedrine to increase and stabilize hers and the baby’s blood pressure. The baby’s heart rate is being monitored constantly, showing decelerations during contractions and then recovering. When necessary, Rourke (and thus the baby) are given extra oxygen by a nasal prong.

At 6 AM Rourke is a 4 centimeters. At 7:30 Dr. Alessandra Peccei comes on duty. Rourke is 6 centimeters dilated and 100% effaced. Baby is seven centimeters from crowning, head becoming visible at the opening to the vagina. As the hours progress, Dr. Peccei punctures the membrane of Rourke’s amniotic sac. Waters flow, contractions pick up, the baby does not move and the heart rate begins to drop. 120, 100, 80. When the doctor stimulates the baby’s scalp, the heart rate responds.

SEGWAY to: VIRGINA APGAR, the APGAR SCORE

Virginia Apgar was a doctor working in New York, a doctor who had an idea, one that Gawande states is “ridiculously simple.” It transformed childbirth and the care of newborns. And as Gawande states, she was an unlikely revolutionary for obstetrics, had never delivered a baby, not as a doctor, not even as a mother. But she would often sit down with someone having trouble and say, “Tell Momma all about it.” She was a surgeon, but joined Columbia’s faculty as an anesthesiologist. She became the second woman in the country to be board certified in anesthesiology, helping the practice to have its own division, on equal footing with surgery. Gawande writes that Apgar was appalled by the care many newborns received.

“Babies who were born malformed or too small or just blue and not breathing well were listed as stillborn, placed out of sight, and left to die. They were believed to be too sick to live. Apgar believed otherwise. She had not authority….She was not an obstetrician. She was a female in a male world. Gawande: “So she took a less direct but ultimately more powerful approach: she devised a score.”

The Apgar score—as it is now universally known, allowed nurses to rate the constitution of babies at birth on a scale from zero to ten. An infant got two points if it was pink all over, two for crying, two for taking good vigorous breaths, two for moving all four limbs, and two if the heart rate was over a hundred. Ten points meant a child born in perfect condition. Four points or less meant a blue, limp baby.

RESULTS

Throughout the world, virtually every child born in a hospital came to have an Apgar score at one minute after birth and then again at five minutes after birth. It became clear that a baby with a bad Apgar score at one minute could often be resuscitated, with doctors, nurses providing warmth, physical touch and oxygen, to help the baby gain an excellent score at five minutes.

The results: neo-natal units! The score also affected the management of childbirth. Spinal and epidural anesthesia were found to birth babies with better scores than general anesthesia.

Prenatal ultrasound became a regular process used to detect problems for delivery in advance.

Fetal heart monitors became standard. All these changes, these procedures have produced amazing results. Gawande writes: “In the US today, a full-term baby dies in just one childbirth out of 500, and a mother dies in less than one in 10,000.”

FINAL THOUGHTS How did Dr. Apgar’s work make doctors BETTER?

The Apgar Score changed everything, being a practical way to calculate and give doctors an immediate feedback as to how effective their care had been.

The Score also changed the choices that doctors made concerning how to do better! They poured over the Apgar results, wanting to encourage results that would make every doctor, nurse, from the most experienced to the novice, a better practitioner.

And our patient, Elizabeth Rourke? She had almost 40 hours of labor and finally a Cesarean section. Katherine Anne was born at seven pounds, fifteen ounces, brown hair, blue-gray eyes, and soft purple welts where her head had been wedged sideway deep inside her mother’s pelvis. Her Apgars: 8 at one minutes, 9 at five minutes—nearly perfect.

MORE TO READ: Find more wonderful information about Health Care in Gawande’s books: BETTER: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, COMPLICATIONS: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science, BEING MORTAL: Medicine and What Matters in the End, THE CHECKLIST MANIFESTO: How to Get Things Right

I’ve read them all.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterest

November 14, 2021

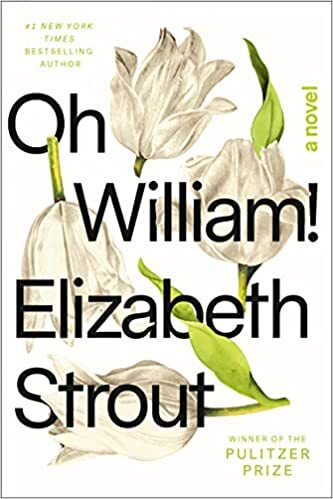

Discussion, Review of Elizabeth Strout and OH WILLIAM!

In her latest novel, OH WILLIAM!–Lucy Barton, the main character and voice in the novel, tells us that when she learns William had been having an affair with her friend, “a tulip stem inside me snapped. It has stayed snapped, it never grew back.”

Elizabeth Strout hated being a lawyer: “I couldn’t stand up for anybody, even when I believed in their case.” After six months, she left to do the adjunct professor thing in Manhattan, teaching literature—writing. Strout has admitted that there’s nothing romantic about being rejected, but she never gave up. “I often had only two hours every three days to work; I had to make the most of it.”

She succeeded, using her early life in Maine to create Amy and Isabel, Abide with Me and then Olive Kitteridge, her Pulitzer Prize winning collection of stories about a cantankerous wife, mother and former teacher. Example: Olive’s only child, Christopher, has just married Suzanne. Olive leaves the party, goes into the married couple’s bedroom… she crosses the pine floor, gleaming in the sunshine, and lies down on Christopher’s (and Suzanne’s) queen-size bed. …It pleases her to think of the piece of blueberry cake she managed to slip into her big leather handbag—how she can go home soon and eat it in peace, take off this panty girdle, get things back to normal.

…Then later, Olive sees the bride’s favorite pair of loafers. She takes one, smashing it into her purse with the blueberry cake. That’s Olive.

In Olive Again, 2019, Strout deals with Olive’s second marriage, her son’s divorce, her need to move to the Maple Tree Apartments. There she meets characters who have appeared in Strout’s work: Amy and Isabelle, The Burgess Boys. This expansion of the lives of former characters reinforces Strout’s oeuvre and the world she’s created. Toward the end of Olive Again….her mind twirling around, Olive suddenly remembered catching grasshoppers as a child, putting them in a jar with the top on, her father had said, ‘Let them out, Ollie, they’ll die.’

Her next, My Name Is Lucy Barton, allowed Strout to explore new artistic territory by creating Lucy, a writer with a background, a life experience worth exploring, exposing. Strout followed with a collection of stories, Anything Is Possible and now with Oh William! — Strout the writer, Lucy Barton her muse.

In MY NAME IS LUCY BARTON, Lucy is hospitalized for complications from appendicitis. Away from her children and husband, she awakens to find her mother sitting in the hospital room. There is little positive history to connect these two, but the mother has traveled from Amgash, Illinois, a fictional small town Strout created where people cling to the land, seeking comfort in the narrowness of what they know. The mother’s arrival gives rise to Lucy’s childhood pain: her father locking Lucy in a truck with a snake; the tiny cold house; Lucy staying late at school where she could study, be warm, meet the gentle teacher who believes in Lucy, helps her escape Amgash, attend college where she begins to write about her life, where she meets and falls in love with William!

As she wrote the story collection, ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE, I envision Strout with piles of notes (her process, see previous post) while laboring over themes and visual details to create characters that might have walked the streets of poorer towns, maybe even those in her beloved Maine. In her story SISTER, Lucy has finally returned to Amgash to visit her sister and brother.

Lucy moved close to her sister, she rubbed her knee. “Oh, that’s disgusting. You are not icky, Vicky, you’re–” “I am so icky, Lucy. Just look at me.” Tears keep coming from Vicky’s eyes. They rolled down over her mouth, with its lipstick. “You know what?” Lucy said. She stopped rubbing Vicky’s knee and started patting it instead. “Cry away. Honey, just cry your eyes out, it’s okay. My God, do you remember how we were never supposed to cry?”

Strout left a thread in MY NAME IS LUCY BARTON, Lucy’s father, a WWII vet, won’t accept Lucy’s marriage to William, whose heritage is German. Now in OH WILLIAM! Strout explores that thread.

LUCY’S HISTORY…

Lucy married William, they lived in New York City, had two daughters, then later divorced. In Oh, William!

Lucy’s second husband, David, has recently died, her daughters are grown. William has had women, but finds himself lonely. When he asks Lucy to go on a trip with him, help him search for a half-sister he has newly discovered on an ancestry website, Lucy questions her current role, but then agrees. The book is a trip of remembrance, of adaptation that all couples experience. Memories of their lives, their daughters lives past and present are shared. They talk about Catherine, William’s deceased mother, questioning how this step-sister might exist. The trip revives memories, Catherine putting William in a nursery school. “I’d cry every day at that place…Lucy, I would cry–the kids would circle around me at recess and they’d sing, ‘Crybaby, crybaby.'”

Lucy listens, silently questions how William will react if they actually find this woman, this half-sister.

With MY NAME IS LUCY BARTON and now OH WILLIAM! Strout has mastered a clipped, direct style, scenes that flow into one another, revealing a character’s thoughts, ordinary, maybe even simple, but always revelatory…. he was wearing the khakis that were too short and I had the same reaction I’d had when I first saw him wearing them at the airport the day before, but I was tired from my night and I did not feel it as strongly.

…so often I had the private image of William and me as Hansel and Gretel, two small kids lost in the woods looking for breadcrumbs that could lead us home. …that the only home I ever had was with William…I’m not sure why this is true, but it is. …being with Hansel–even if we were lost in the woods–made me feel safe. I wrote in the margin, YES! Strout relates a character’s thoughts, questions, pains, and the questioning we all have about our closest relationships.

I was in rural Maine and what had just come to me was an understanding, I think that is the only way I can put it, of these people in their houses, these houses we passed by. It was an odd thing, but it was real, for a few moments I felt this: that I understood where I was…that I loved the people we did not see who inhabited the few houses and who had their trucks in front of these houses. This is what I almost felt. This is what I felt.

Again, we check in on our feelings as they flow through us, pinning them down as we question and then say YES.

Every reader comes to a novel with their own past, their own anxieties, beliefs and a view of the world. Getting lost in story can be pleasing, but it can also arouse questions. Reading Elizabeth Strout is a journey. It provides a look at the reality of lives, not always pleasant, not always redeeming. Her characters are flawed, as we all are. But people change and grow. Strout has penetrated those changes in her work. Maybe that is why she again finds her characters gathered on her table of messy notes, waving conjoling, encouraging her to write more about them. I hope she does.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterestNovember 7, 2021

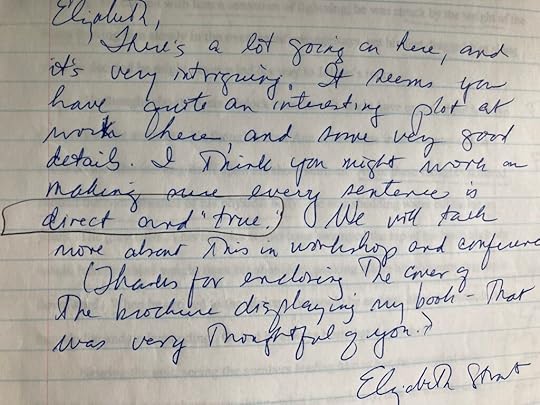

When Elizabeth Strout Critiqued My Pages

An author from Maine, now living and working in New York City, Elizabeth Strout published her debut novel, Amy and Isabelle, in 1998. The basic storyline echoed some unfortunate headlines, examining, “the close relationship between Isabelle and her teenage daughter Amy, how their relationship comes to be strained after Amy is groomed by her much older math teacher.”

A reviewer in the New York Times summarized the new writer’s talent: “…the story’s true drama lies in the palpable, intricate way it examines the ‘scrape of longing’ that drives these characters toward human contact, leaving them raw and bleeding yet also more fully alive.”

I read her debut, then her second novel, Abide with Me, (2006) summarized as: a religious leader, struggling with the death of his wife, in a small New England town, in the 1950s. Still New England, but Strout flexing her writing muscle, wowing some of the reviewers while finding her way. She would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Literature on March 25, 2008, for creating the amazing character who appears in a collection of short fiction: OLIVE KITTERIDGE. Now with no place to go but up, Strout published THE BURGESS BOYS in 2013, a novel with Maine roots that takes place in New York City.

I GET TO MEET HER

In the summer of 2006, I did what had become a delightful summer habit, I would attend a writing workshop at the University of Iowa, in Iowa City. The catalogue listed Elizabeth Strout, offering a weekend course on writing THE NOVEL. I signed up.

What kind of a teacher was this future Pulitzer Prize winner that auspicious weekend? Well, nervous, apologizing that this was a new experience for her—but talking about her passion, which of course is writing.

She spent the first day explaining how she’d come to be a fiction writer. I don’t think attendees, myself included, found this very helpful or exciting—but looking back, Elizabeth was truly sharing the nuts and bolts of her writing process, encouraging those of us who might also be experiencing an unusual start, a bumpy start.

Married to her first husband at the time, Strout mentioned that her in-laws didn’t understand why her dining room and a room in her basement were littered with scarps of paper, quick ideas that she jotted down, pages and pages, most-often written in long-hand and not always placed in organized piles. (Strout later taught herself how to compose at the computer) but I understood that moments of creation often come through the fingers, and at the time, longhand was her process. Though I don’t want to bore you with these details, as a struggling writer, I found it all fascinating.

MY LITTLE GIFT & HER ANALYSIS

Before that weekend, I’d found a furniture advertisement in a women’s magazine, the usual, except that the table had a neat pile of books and Strout’s AMY & ISABEL was prominently displayed. I brought the page with me, clipped it to my homework assignment.

Elizabeth had asked us to provide one chapter from our work-in-progress. I was working on my second novel, THE MOON DOCTOR, (still unpublished) about a burn victim who finds his traumatic experience has given him the power to heal others–without the need for medical school.

Strout read ten pages from a chapter in the middle of the book. Her final comment:

There’s a lot going on here, and it’s very intriguing. It seems you have quite an interesting plot at work here, and some very good details. I think you might work on making sure every sentence is direct and ‘true.’ We will talk more about this in workshop and conference. (Thanks for enclosing the cover of the brochure displaying my book. That was very thoughtful of you.) Elizabeth Strout.

For interested fellow writers, she underlined phrases, stating that they WEAKENED my presentation. Her message: these sentences were not true to my voice.

Example: All of these thoughts skittered around the encumbrance of his physical body. YES, I agree, a truly horrible sentence.

He slowly removed the IV catheter from Jolene’s arm. He’d forgotten a 4by4 and instead watched a snake of dark blood pool down onto the bed linen. Strout wrote: good use of detail.

Was Strout a great teacher? No. I know she’d be so much better now, as I have listened to her interviews, she being more assured, eager to share her writing process, because she has succeeded, truly succeeded. And her life has radically changed, her fourth novel, MY NAME IS LUCY BARTON, performed on Broadway, the dialogue spoken by Laura Linney.

A FEW MORE WORDS ABOUT ELIZABETH STROUT…so n ext week, I will review Strout’s recent novel, OH, WILLIAM! when Strout is once again in the world of Lucy Barton, the main character of MY NAME IS LUCY BARTON and her collection of short stories, ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE.

Thanks for reading.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterest

October 31, 2021

My INDEX TO AUTUMN

DEFINITION of INDEX: an alphabetical list of names, subjects, etc., typically found at the end of a book.

AFTERNOON: angle of light in; soccer games in; time to rake leaves, walk in;

APPLES: bobbing, drying, picking; for pies; green, red, yellow; teachers dislike for–truth revealed;

ARGUMENTS DURING: regarding football games on TV, leaf raking;

BABIES: record number conceived in; riding in strollers for walks;

BASKETS Of: apples, cinnamon bread, dried flowers, pumpkins;

BIRDS: departure of; feeding with break crumbs, pumpkin seeds;

BLANKETS: washing, adding to beds, especially in colder climates;

BOTTLES: contents of: cider, wines, window cleaner;

CANDY: see cavities;

CAVITIES: see candy, Halloween;

CHILDREN: arguments concerning leaf raking, trips to ER after football, soccer games;

CORN: husks; stalks in fields; sweet with butter;

CROPS: abundance of; ruined by rain/winds; varieties: cranberries, melons, pears, yams;

DYING: sunlight along the grass; light in the tops of the trees;

FOOTBALL: games, scores, tailgates; see also arguments about…

FROST: first; preparation for; harm to delicate plants not covered; see cultivars;

GRAPES: arbors of; jams, jellies; wreathes made from branches of;

GRASS: color of; reduced growth of; spreading roots;

GREEN: grass after rainfall; see photosynthesis;

HALLOWEEN: cornstalks; costumes; light on the night of; rain on the night of; scarecrows; tricks by children; See shaving cream, toilet paper;

HARVEST: moon;

HUSBAND: arguments about football games and raking leaves;

INDIAN SUMMER: stories, length of; discussion as to whether term is politically correct;

KILLING FROST: see frost;

LAWNS: covered with leaves; light from sun in late golden afternoons;

LEAVES: gold, plum, red, yellow;

MOON: harvest; full; lover’s moon; yellow; zenith hour;

PHOTOSYNTHESIS: cessation of in plants;

PUMPKINS: carving of; orange; size; transformation; See husband, children;

RAKE: varieties: bamboo, iron; plastic; verb: arguments pertaining to…

SLANT: of sunlight;

SQUIRRELS: everywhere; eat Indian corn off porches; bite into pumpkins;

SUNSETS: amazing…

TEENS: hanging in groups; homecoming; tricks on Halloween; football; testosterone;

TESTOSTERONE: see babies, teens; parenting;

WASHING: see windows;

WELCOME: see wreaths for doors;

WINDOWS: see washing;

WREATHS, on doors: corn husk, grape vine, soon to purchase evergreen; also, wreath of smiles. Autumn is the loveliest month.

Thanks for reading. This was written when my children were young. I save everything.

THANKS FOR THE GORGEOUS PHOTO FROM: Scattered Thoughts and Rogue Words

Facebook Twitter LinkedInPinterest