Delia Marshall Turner's Blog, page 10

February 19, 2024

Participation Awards

I am one of the most competitive people in the world, except most of the time. Somebody at work once said I was competitive, and I answered honestly, “Only if you compete with me.” My coworker didn’t quite understand that. I come across as intense, I realize, and I don’t lie about my results. That can come across as boastful, especially when people have decided to underestimate me to begin with. Thus, they apparently decide I’m grandiose, but they ignore all the awful stories I also tell on myself at the same time.

However, as should be obvious by now, I do really like medals. That’s actually not because I’m competitive, it’s because they are the best kind of participation awards. I carry the medals home from the event with me. I put them in my jeans pocket and check them to make sure they’re still there. If I am flying I put them in my personal bag. When TSA alerts to the circular discs, I am happy to explain. I definitely brag about the shinies, but it’s because it comes as a perpetual surprise that someone gave them to me and I want to share the joy. Yes, I am about six years old when it comes to medals.

This fondness for hardware partly explains why I so often competed in the state games of New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Medals from state games

Medals from state gamesIn an earlier post, I talked about the Philadelphia Division. The Philadelphia area is a tiny percentage of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, but it contains most of the state’s competitive clubs. In the rest of the state, fencing is sparse. The Keystone State Games were held almost every year, in a place that is more central to the state, and I would often go. As long as I kept my expectations low for the event, it was a nice outing.

Why low expectations? Two reasons: One, the organizer, Ed, was a sweetheart, but he also fenced at least two weapons, maybe three, and because he was a nice guy, he figured that if the Games were happening, everyone should have a chance to fence whatever they wanted, including him. Therefore, the tournament took forever. The 11-person event that took four and a half hours wasn’t even unusual. One year, my 20-person event took seven and a half hours to fence, when it should have taken perhaps an hour and a half.

The other reason for keeping my expectations low was that the quality of the fencing varied widely; some of the fencing clubs in the state were isolated and not terribly competitive. The event got better over the years, mind you, and the last time I went even the refereeing was good (except that our ref decided it made sense to process a pool of over-50-aged women with tremendous efficiency, and a couple of us started having asthma attacks).

There was usually an open combined (men’s and women’s) event, a veteran event, and a women’s event in the Keystone State Games, and I often did well. In 2003, for instance, I finished third for the open (all ages, both men and women), first for the women, and first for the veterans (over-40, also mixed). Ergo, lots of medals.

Then why are there so many more New Jersey medals in the photo than there are from Pennsylvania? Well, for one thing, because New Jersey is very small, and therefore much of it is actually closer to Philadelphia than much of Pennsylvania. And besides, Gladys, who usually organized the Senior Games, is an even nicer person than Ed, and she decided that there should be medals for each five-year age group in the over-50 events. That meant I usually got two medals, one for the whole event and one for being the highest finisher in my age group. In other words, I got an award and a participation award, both at once.

Oh, yeah, and one other thing: Sometimes, I confess, we had as few as four people in my event, so I would have had to work really hard not to get two medals.

It was worth going, though, because it was always a pleasant outing. Gladys had contacts and got good referees for us, which was a huge deal. Sabre is fast and complicated, and points are often determined by a combination of who started first, who missed, whether someone parried, and various other considerations. A good referee who understands the game thoroughly is essential. The problem with refereeing veteran events is that on top of all the precision, speed, tactical choices, and strategy, you also have inevitable physical slowing, awkwardness, and distraction of an older physiology. It is hard for some referees to realize that just because we look clumsy, that doesn’t mean we’re not working at a high level.

Also, veterans talk a lot. And we argue, flirt, and digress. So not only does the referee have to be good, he or she has to keep cool under some very bizarre and ridiculous pressure.

One year, my friend Donna had come down from Massachusetts for the Senior Games, because it wasn’t easy to find good veteran competition (sometimes we called our best opponents, if they were registered, to make sure they were actually coming). Donna is younger and faster than me, and very good indeed. The referee for our bout, a young man named Idris, leaned casually against the wall and started the bout, clearly expecting that he could be chill with the oldsters.

Then Donna and I fenced our first touch.

We went up and down the strip, with all kinds of tempo changes, deceptive actions, and (I confess) yelling. Idris said, “Halt.” He blinked and said, “I wasn’t ready for this.” He didn’t even try to call the point. We all laughed, knowing it was a compliment, as he stood up, settled his shoulders, and paid very close attention for the rest of the bout.

I got two medals that day, one for winning the whole event and one for my five-year-age group, which I believe was for age 65-69. And the next year, I got the same two medals, too, defeating my friend Jennette, an experienced foilist who had decided on a whim to start fencing sabre, in an epic gold medal bout. When Gladys was awarding the medals and I won gold for the 65-69 age group, a gentleman on the sidelines blurted, “How old are you?”

Now, I realize, the state games medals too can go in the recycling bin. What really matters, what I want to hold on to, isn’t actually the medal. It’s Idris (who was already a really neat person in his teens) saying, “I wasn’t ready,” the bouts with Donna and Jenette, and the man saying, “How old are you?”

Those moments are the real participation awards. I treasure them. When I think of those moments, and about all the friends I used to see at those events, I smile.

February 18, 2024

Road trips to the industrial park

It’s supposed to be a two and a half-hour drive down I95 from my house to Silver Spring, Maryland, but it’s more like three hours, or maybe four on the way back when I’m tired.

Fencing clubs are usually in suburban industrial parks, old factory buildings, or storefronts in tumbledown areas, because you need open space, high ceilings, dependable floors, parking, and low rent. DC Fencers Club is in an industrial park near a couple of roofing companies and an automotive supplier, and I have been there more times than I can count, or than these medals show.

DCFC medals

DCFC medalsThe head coach at DCFC, Janusz, is a very good guy, and his club puts on three yearly events that I particularly liked: The Captain Steere Open, the Tom Wright Memorial, and the Amazon Open.

The Captain Steere is a small informal event and not a big deal, it’s just that it tends to happen at a convenient time of the year. I’ve fenced it at least twice, and one of those times was because my mother wanted to see me fence and because my sister could drive up to hang out with us. However, fencing is not a spectator sport. Except maybe for national and international events when the two finalists are up on a well-lit raised platform with a mic on the referee and great big scoring machines, it’s hard to figure out what’s happening.

Also, I tend to be grouchy when I am competing, and all my life my mother liked to do something I call “poking the bear,” which was to make sarcastic comments until she got a rise out of me. I was already grouchy with adrenaline, so I had to walk away from her a few times; she was not well because of her Parkinson’s, and it wouldn’t be fair to tell her off.

I had a good day, and was up against an acquaintance named Keith in the gold medal bout. When I won the tournament, Keith’s coach, the owner of the club, Janusz, beamed with delight, and said to me, “See how easy it is, how simple, when you do it right?” Then Janusz asked me to help him show Keith what he was doing wrong, and I did, because I believe we’re all in this together and because Janusz is a neat guy.

The Tom Wright Memorial is another tournament at DCFC. It’s a “veteran” tournament (for fencers who are over 40), and is fenced mixed, meaning men and women can compete, but there is a separate gold medal for the highest finishing female fencer and for the highest finishing male fencer.

The first time I fenced the Tom Wright, I ended up in the gold medal bout against a fencer named Steve who is around my age. I have known Steve for years, and he is one of those gentlemen who is nice and a little sweet until he loses a bout. I have seen Steve absolutely helpless with outrage, and literally frothing at the mouth (little bubbles) because he could not possibly have lost. He goes around explaining that to everyone.

Our referee was another over-40 fencer, a person named Larry who is the distilled essence of fencing eccentricity. Larry believes he knows everything and he is always right, and he talks a blue streak. He is also, because he is even older than me, an utter fossil.

There is a halfway break in a 15-touch sabre fencing bout, and I was leading at the break. During the one-minute pause, my referee, Larry, went over to talk to Steve. I suddenly realized he was telling Steve what to do; in other words, he was coaching him during the bout he was refereeing. This is expressly forbidden.

Steve rallied after the break and beat me, and I said to Larry, “Larry, you can’t do that!”

“You know how Steve is about losing to women,” said Larry, in a reasonable tone. “Anyway, you already had the gold for the women.”

Another DCFC coach who was nearby while this was going on, Darius, came over and told me I should ask him to come referee next time.

The next time I did the Tom Wright, Larry wasn’t refereeing; we had good refs, thank goodness. It was an excellent event, with fifteen fencers, and it was very strong because there was a national over-40 event coming up. The winner would earn a B classification. Everyone was fencing at the top of their game, including me. And now, I was once again in the gold medal bout, against another man I knew well, Chris. Chris didn’t have a B yet, just a C, and he could smell that B rating.

So Chris got excited. Chris went fast, and when that didn’t work, he went faster. This happens to a lot of older fencers, who remember being fifteen, but who don’t realize that they don’t have fifteen-year-old smoothness and strength any more. I, on the other hand, started when I was already too old to go fast, so I have my ways of compensating, and I beat Chris.

Afterwards, he knew what his mistake had been and laughed ruefully about it. (He earned a B at the next national event). And once again, I got the women’s gold medal.

The Amazon Open was the third event I always went to at DCFC, and it was because of my friend Val. The Amazon was originally just an epee event (Val is an epeeist), but she decided to add a sabre tournament, and asked me to talk it up among my friends. She is one of the kindest and most reliable people in the world, and I would do anything for Val, including drive to DC in June to fence in a space that was, for a long time, not well air-conditioned. Besides, though it was never large, the Amazon was a lot of fun. Val always found neat prizes for the competitors, and provided good snacks. And though most of the competitors were usually young women, I could look forward to seeing a few over-40 friends, including Laura (a trauma surgeon) (Val is an otolaryngologist) (did I mention that fencers tend to be amazingly overqualified?) (did I mention that at one Amazon Laura, Val and I posed for a photo as “The Three Doctors?”). It was always good fencing, too.

And then, one day, Val texted me a photo. She had acquired a neat trophy for the next Amazon sabre competition. She had named it after Laura and me, because we always showed up for the Amazon.

Yes, I cried.

Yes, the reason I drove down to DCFC so many times, in spite of how dispiriting I95 is, in spite of the wear and tear, and even in spite of Larry, was because the people there were kind to me. Janusz, Darius, Val, Laura, Chris, and all the other nice people I so often saw there, always made me feel like I belonged. And now there’s something with my name in it down there, even though I’m not fencing any more.

Turner-Johnson Trophy

Turner-Johnson Trophy

February 15, 2024

All the unidentified medals

When I started fencing in the 1990s, the Philadelphia Division of USA Fencing had three clubs, and each club ran regular small tournaments. Most competition in the US at that point was at the division level, and though the other two clubs in my division were at least an hour away, I went to every tournament I could.

This explains one enormous category of my medals.

65 medals from 1996 to 2018.

65 medals from 1996 to 2018.Once the division had a handful of women’s sabre fencers, the clubs happily started hosting women-only competitions for us, alongside the regular mixed events because, more entries meant more entry fees. Clubs made a good bit of their income by offering tournaments, plus it was a way for their fencers to gain experience. Besides, any tournament over 6 people earned the winner an E classification, and any tournament over 15 people had the possibility of even higher classifications. The more rated fencers a club had, the higher they were seeded in regional and national events, so it paid off back then to create as many local tournaments as possible.

There were only three clubs in the division back then, and only one of them was actually in Philadelphia: Fencing Academy of Philadelphia, where I started out and fenced for a long time. It was in a storefront in West Philadelphia, a brisk walk from the Philadelphia train station.

Bucks County Academy of Fencing was Mark Holbrow’s club in New Hope, PA, and it was located in a little theater building in charming New Hope. Tournaments at BCAF were held either in the basement, where we kept hitting the columns that separated the strips, or in the second floor, which was more spacious but slippery and not air conditioned. Circle d’Escrime was in Sellersville, on the second floor of another charming building, with lots of varnished wood and brick interior walls.

None of the three clubs really had any sabre, so sometimes the women’s event was me and my teammates Cindy and Louise, making a road trip of it. We also often entered the open (meaning mixed men and women) event, so that we could get some more fencing for our travel, and so the clubs could have bigger events. I can’t tell you how many tournaments I entered in order to “lend my rating,” because as long as I finished in the top half of the tournament with my D (later an A) someone was going to get a better rating.

I could usually beat Cindy and Louise, which explains a chunk of the 29 gold medals, and even when more women started moving into sabre, I was still the most experienced woman in the division and was still winning women’s events into my late sixties. I often medaled in the mixed events, too.

But for the most part, they all used the division medals, even the newer clubs that came and went. And for the most part, no one labeled the medals, not even with the year. So I have 65 Philadelphia Division medals – 29 golds, 13 silvers, and 23 bronzes – and no idea where or how I earned them.

There. I’ve done it. Tomorrow is trash day in my neighborhood, and every one of those Philadelphia medals, and every experience they represent, is going into the recycling. I may have to make two or three trips to do it, because those things are heavy.

That wasn’t nearly as hard as I thought it would be.

Unrealistic

Because I was willing to risk making a fool of myself, I have collected many embarrassing moments, and a handful of precious memories. I was thinking about one of those memories today, because Henri Sassine died February 12. He was the Canadian coach of nine athletes at five Olympics, including his daughter Sandra, who fenced in two Olympics herself.

I didn’t know him personally, and he didn’t know me, but we did cross paths once.

In 1997, I flew to a tournament in Montreal. My kid was fencing in it, and a bunch of the club members were going, so I decided to go and fence too. I was in way over my head, but then I was always in over my head. Montreal was a “designated” event for US fencers, meaning you could earn national points, and a lot of very serious competitors were there.

In my first round seeding pool, I would be facing one of Sassine’s fencers. The girl, though seeded high, was having a very bad day. She lost a bout she shouldn’t have, and when her small, energetic coach came over to check in on her, she was tearful. He looked at the order of bouts, saw that she was fencing me next, and said to her in French, loudly enough so I could hear him, “Take this one out and I will come back and tell you what to do,” and he went away to coach his other fencers. He wasn’t being intentionally insulting; he didn’t know I understood French. All things considered, it was good advice, because I wasn’t as good as she was. The only problem was that she was indeed having a bad day, and I beat her in that next bout.

Sometimes I worry that when I tell these stories, it comes across as bragging. That’s because it is. But I’m not bragging about beating Sassine’s student. She was just having a tough time and I happened to be there for it.

I’m bragging that in spite of everything, I showed up. If I hadn’t entered the event in the first place, if I had respected my limits, I wouldn’t have earned that tiny victory over myself, and it was all the more precious because Sassine had dismissed me so audibly.

Of course, I didn’t earn a medal. Instead, wheezing with exercise asthma and so exhausted I said “Thank God!” when I was finally eliminated, I finished tenth out of 43 (still a great finish for me). Then I jammed myself into the back of my coach’s car, cramping up almost immediately, and they drove me home to Philadelphia. I made it back in time to teach my classes the next day.

I’m a big fan of being realistic, mind you. High expectations are the devil, and I have seen far too many people crushed by losing when they thought they could win. But low expectations are the devil, too. I was fencing in that event because they let me, and if I hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t have a story to tell about it. It’s all about the stories, after all. That’s what is left when everything else is gone.

February 10, 2024

Not my job

Fencing, like all sports, is full of opportunities to do things that aren’t actually the sport itself, such as refereeing, repairing equipment, running tournaments, serving on committees, and coaching. Many adult fencers migrate into those tasks, and I have tried out most of them. The first one I tried was coaching.

In 1995, when I had been fencing about a year, my coach Mark said he needed someone to run the basic adult class at the club. The United States Fencing Association offered “Coaches College,” a week-long summer program at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, and he thought I should go and learn to coach. Mark said it would be a great opportunity for me. I told him what my mother said about him: “That man must be some salesman.” It made him go red in the face and laugh.

I knew he needed a part-time coach. I also knew he preferred not to hire people from outside the club because they cost too much. I went to Coaches College anyway. It sounded like an adventure. I try never to turn down adventures.

The OTC was a large campus in the middle of a very small city, at 6000 feet in the midst of mountains. The fencing headquarters was in the OTC as well. I assume we got our training facilities at a reasonable cost. We were sleeping in plain dorm rooms, but we were eating in the athlete’s cafeteria, and training in one of the big gym buildings, just as the Olympians did.

Though the OTC wasn’t a big showy place, it did have its glamors. The first day, before our program started, the women in the fencing group all drifted over to one side of the gym and were staring down through the glass wall separating us from another gym one floor down. We were awed, transfixed, and soon the men in our group wandered over to find out what we were looking at. We just pointed, but the men kept peering, unable to see what we saw.

To them, it was just some little guys doing exercises. To the women, however, the male gymnasts below were a matched set of absolutely perfect, utterly tiny superheroes, doing astonishing things, with ease, and we all thought they were utterly gorgeous. I don’t think the guys in our group ever understood what we had been looking at. To them, the ideal man had to be over six feet, with prominent muscles and a big jaw.

The cafeteria was probably the best thing about the whole facility, though, because it served healthy food of every possible variety and because we could eat as much as we wanted with our OTC credentials. The credentials didn’t work very well; they were supposed to be personally authenticated by palm scan, but the process wasn’t well developed yet.

There were some wrestlers in the athlete cafeteria, and sometimes we would see other athletes at a distance, but mostly they (and we) were too busy to roam. I bought a T-shirt in the gift shop, because I knew no one at my job would believe I had actually trained there (I was right).

Our group was a real assortment, and though there were some experienced coaches and some active fencers, I realized pretty fast I wasn’t even the biggest novice there. My roommate, for instance, was completely at sea. Most of us were there because we didn’t know enough yet.

Our teachers were all legendary coaches, including Alex Beguinet of Duke University, Abdel Salem of the Air Force Academy, and former Olympian and sabre referee Ed Richards. Alex is French, a puckish, cheerful tiny big-nosed Frenchman who adored playing practical jokes on his students. Abdel is Egyptian, an epeeist and another former Olympian, tall, amiable, deliberate, and monosyllabic. Tall, craggy Ed was peppery, opinionated, and abrupt, in keeping with his sabre background.

The curriculum was ambitious, even if the session was only a week; the teachers were trying to teach some of us how to fence in the first place, while challenging the experienced people. We all did a lot of footwork and bladework, and played many tactical games. I recognized much of the material from Mark’s classes, and it was reassuring that he wasn’t a maverick. There are a few of what people call “hobby coaches” in fencing, and you are never sure if your own coach is one of them, until it’s too late and your skills are outdated or peculiar, but permanent.

The main focus of the program was the core skill of coaching fencing: the individual lesson. One-on-one, a fencing coach works with a student, teaching the correct action at the correct distance with the correct form. The coach must give good cues, at the right distance, with proper timing, so that the student can see when they are supposed to hit, and how. As the student adapts and becomes more skillful, the coach has to adapt as well. Coaches thus absorb many, many solid hits, often from clumsy students. I was glad I had splurged on one of those buffalo-hide coaching jackets, though I felt a little foolish in it.

The last day of instruction, to get Alex Beguinet back for all his practical jokes, we stole his fencing glove while he was out of the room and sewed the fingers together. He was agreeably baffled when he put it on, though we knew he must have realized what happened the moment he picked it up; apparently it was a tradition at Coaches College to pull a final prank on Alex.

There was a paper exam, but that was easy. For our real final exam, we had to give a mock lesson to a fellow student. The night before, I slept in another classmate’s room, because my own roommate was panicking even more than I was, and I just couldn’t take it. I knew how she felt, because I was sure I wasn’t going to pass that test. I hadn’t mastered the cues. I didn’t know the correct distance. I had only been fencing a year.

When it finally came my turn, my demonstration lesson in the exam room was indeed stiff, uncomfortable, and awkward. The observing coaches stopped me, asked for clarifications and corrected me, and after my “student” (a fellow classmate) left the room, they pointed out–at length–what I had done wrong. Then they said, “Thank you,” and I left.

Outside, people asked me how I had done and said, “They just said, ‘Thank you,’” and I began to cry.

The guy who had been my “student” wrapped me up in a hug. But another classmate, young Stefan, said to me, “Did they talk to you?” I nodded and told him they pointed out all the things I had done wrong. “Then you passed,” he said firmly. “They only talk to the ones they pass.”

In the meeting afterwards, they called my name toward the end of the list of people who had passed and, as I went up, overwhelmed, to get the certificate, the whole group sang me “Happy Birthday,” because it was my 44th birthday.

Some people didn’t pass, including my panicking roommate.

After the celebration, I asked Ed Richards why I had succeeded. He said, “We knew you were nervous. But you knew some of the material and we saw how you were doing over the week. What do you think this is, a make-or-break thing?”

Well, yeah. That’s exactly what I had thought, because that was how it was presented.

Before we all headed home, a bunch of us spent the day on nearby Pikes Peak to blow off some steam, including fellow students Woody and Stefan. Stefan threw snowballs at me, and I should have realized something then.

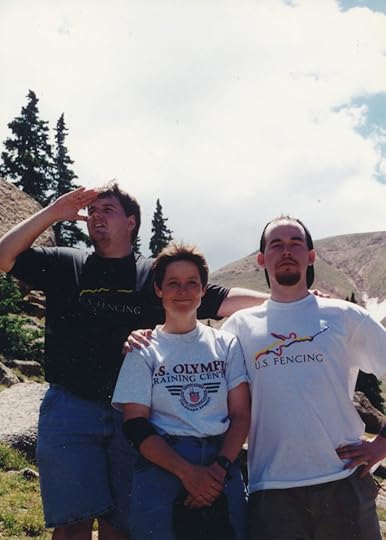

Woody, Stefan and me posing on Pikes Peak

Woody, Stefan and me posing on Pikes PeakIt was a long day, and we got back from Pikes Peak and turned into the USOTC at exactly the moment the shuttle was due to pick me up to go to the airport. I grabbed my pack and ran. I looked back and waved. Stefan, (the young man on the right of the photo above), jumped out of the back of the truck and ran a little toward me. I waved again, he waved back, and I left.

It wasn’t until I was actually on the plane that I realized that apparently, I had been back in middle school, and that one of my classmates liked me.

I was 44 years old, happily married, with a teenage kid and a husband of nearly twenty years, and here a very nice young man thought I was cute. I sat there in my airplane seat, my chest bubbling with amused delight, absolutely astounded. Somehow, that little incident seemed even more affirming than passing the test.

When I got back home, Mark asked me to lead the adult beginner class at the fencing club. Hesitantly, I agreed, though I didn’t really have time. Toward the end of the class, after I thought I had acquitted myself pretty well, Mark came over and pointedly started re-teaching everything I had already covered, as if he was teaching me by example and pointing out all my errors. It was condescending and dominating, and I was annoyed.

The thing was, I didn’t necessarily want to be one of his coaches in the first place. I was doing it as a favor to him and as an adventure for myself. Apparently, he didn’t understand that. Therefore, after the class was over and the students had left, I politely went to Mark and said I wasn’t going to be able to teach the adult class after all. “I’ve already done my student teaching,” I said firmly.

I never coached at my home club. I’m not sure Mark ever understood my reasons.

But I couldn’t make fencing my job. I already had a job; it was how I paid for fencing.

February 5, 2024

A sabre soul

I have won many medals at national events, but I most certainly did not win any at my first one. I didn’t come close.

It was in 1996, in Richmond, Virginia, and I had been fencing sabre for less than a year, though I had been in the “concrete box” as a fencing parent for a while.

National events are in convention centers in cities that aren’t on most people’s bucket lists, because we need a lot of space for not very much money. Once you walk inside, it doesn’t matter if it’s San Jose, Palm Springs, St. Louis, Miami, or South Bend. It’s always the same concrete box, with harsh lights and hard floors, with the same people in it that you saw a month or two months ago. At least I could drive to Richmond from Philadelphia.

There are three weapons in sport fencing: foil, epee, and sabre. Foil is intense and precise, epee is methodical and patient, and sabre is for wild souls like me who always wanted to be pirates and who operate on impulse at all times. Fencing sabre feels like flying to me. The sabre is a steel stick with a bell-guard, and you score by “cutting” (though the edge isn’t sharp). It feels like a proper weapon. My husband gave me one for Mother’s Day early on, and it was the best gift he ever gave me.

Before sabre was scored electrically, you had to convince your referee you had scored by going fast (and first) and by hitting hard enough that everyone in the room could hear the smack, hopefully hard enough that your opponent also winced and cried out. I’m only sort of joking. Women did not fence sabre. It was only for men. No NCAA sabre fencing for women. No Olympics. I know a very few women who fenced in open tournaments, and they were brave.

Also, it looked like two rams going at each other horns first, over and over. And there was a lot of yelling.

In 1986, sabre scoring was electrified, with the addition of conductive jackets, gloves, wires, machines, and plugs in our sabres. Suddenly, you could score a point with a touch instead of a mighty thwack, and a few more brave women began trying it out. We were mostly misfits, because coaches were still directing their strongest athletes into foil and epee. Women sabrists were a cheerful and goofy bunch, all shapes and sizes, all ages, united by enthusiasm and by the willingness to show up, even though the general opinion was that we were weird and comical.

I had started fencing sabre at absolutely the perfect moment. I was a beginner, but so was everyone else. I could go to any sabre tournament, anywhere, and I fit right in because none of us fit in.

The poor opinion of women’s sabre was shared by pretty much everyone who didn’t fence it, including my coach. A few days before I went to my first big tournament, he said he was bored, and offered to fence me with just a dagger. It was clear he thought he would be able to teach me an easy lesson. He gave up on that idea very swiftly indeed.

Later, the assistant coach was trying to prepare me for the national event by telling me to lower my expectations. The head coach interrupted her. “You haven’t bouted her,” he said. She made a face at him. She wasn’t wrong, but neither was he.

It would take longer than it’s worth to describe national tournaments, so I’ll just mention a dream I had last week. I was in a huge noisy space, didn’t know where I was supposed to be, I had misplaced my stuff, I was rushing through crowds of people who were talking to each other and ignoring me, I was supposed to face someone who could absolutely kill me but I didn’t know where or when, everyone who could help me was busy with someone else, and I was upset and confused.

It wasn’t even a nightmare.

That’s pretty much how it is at a national tournament, still.

The events are held in large open convention center spaces, laid out with metal fencing strips. Several different events (men’s, women’s, foil, epee, sabre, youth, cadet, junior, senior, veteran, parafencing) are going on at once. Coaches, parents, referees, and fencers are scattered all around, and the clatter of metal against metal is punctuated by loud shrill beeps from the scoring equipment, and by full-throated screams and howls from fencers. There are folding chairs everywhere, and fencing bags. Coaches are arguing with their athletes and with the referees, parents are offering hopeful advice and water bottles (both summarily rejected), the committee that runs things is up on a high platform looking out and down at everyone and trying desperately to keep track, and you are not supposed to bring your own food because the concession stands have to make a living from the fleshy protuberances they call hot dogs. Before competing, you have to find the technicians (“armorers”) who will inspect your equipment to make sure it’s safe and that the electrical bits work. There is inevitably a long line for the armorers, just when you have to be somewhere else. Armorers like to tell bad jokes and fail your equipment. There are vendors where you can buy more equipment, which you also have to get inspected before you can fence.

You also have to officially check in for your event. In 1996, it wasn’t completely computerized; instead, they gave us an index card to hand to our referees once we figured out where we were supposed to be. The locations of our bouts were printed out and taped to the wall somewhere, surrounded by fencers trying to read the sheets, so that no one could see.

You were not allowed to lose your index card. Bad things happened if you did. You handed your card to the referee, who wrote your name on a pool sheet, entered your results, and calculated your finish once everyone had fenced the seven-person seeding pool. Then you waited for the committee to put more sheets of paper on the wall to tell you what you were doing in the elimination bracket.

I had signed up for two events. One was a Division III, which was aimed at encouraging novice fencers like me, and the other was a Division II, which was for marginally more experienced fencers, but which I could enter if I wanted, and I did.

As I expected, I did pretty badly. In each event, I won only one bout in my pool, then won one direct elimination bout, and I was eliminated immediately after that. It was about what I expected, as a 44-year-old novice with asthma. It was no one’s idea of a fantasy first tournament.

Except that it was a triumph beyond my wildest dreams, and both times I was crying with excitement. First, because I survived, and I wasn’t awful. Second, because I earned a classification, or rather two classifications, one after the other.

[Classifications: In fencing, we use letters E, D, C, B, A to seed the preliminary rounds. How did the fencers get those letters? By competing in strong events and finishing well, or by competing in national events where there was the incentive of guaranteed classifications for a certain finish. Thus, if anyone finished in the top 16 of the Division III, they earned an E. If they finished in the top 16 of the Division II, that earned a D.]

People starting out spent years just trying to earn their E. It was a big deal to have a classification. It meant you have proved yourself.

But in women’s sabre? Our event was so small that winning one direct elimination bout put me in the top 16. Thus, I arrived a U (unclassified), and came home from my first national event having earned an E and then a D. People kept congratulating me back at the club, which was embarrassing because it was just due to the numbers.

Others were openly envious. A couple of the young men who fenced sabre complained about how easy it was for women sabre fencers to get ratings. The foilists were likewise condescending, and were sure they could fence sabre if they really wanted, though they mostly didn’t. Even when I re-earned the classifications soon afterwards in tougher circumstances, it was difficult to convince them that what I had done was hard. Heck, I wasn’t even that convinced.

Then, a couple of months later, one of the women foilists, a very strong fencer, decided to fence me in sabre. It was a friendly bout, but she was muttering “I’ve got to beat you” under her breath, and it was clear she had something to prove.

She didn’t beat me.

Later, we were all standing around talking about this and that, and she said, ““That hurt.”

I was apologetic. “Did I hit too hard?”

“No, you cut my tiny sabre soul into bits,” she said ruefully.

My tiny sabre soul was very happy about that.

January 26, 2024

Tricking people so you can hit them

The most common question asked in online fencing groups is “Am I too old to start fencing?” The person asking is usually fourteen. Even though the question gets asked about once a week, everyone replies kindly and says no, you’re not too old, people start at every age.

They’re sort of lying, because what the fourteen year old wants to know is if they can go to the Olympics. For that, they should have started when they were eight, picked wealthier parents, and lived very near one of the top fencing clubs in the country. Even then, their chances are slim. Heck, a lot of people who start fencing don’t end up liking it. It’s really hard, and you don’t have anyone to blame for failure. It’s full of weird rules that are always changing. Also, people yell when they score touches, and referees say things you don’t understand, so you think maybe someone cheated. And everyone in the room at a tournament loses at least one bout, except (sometimes) the winner.

When I started, I was a good bit older than fourteen. It was 1994, I was 43, and I was standing in a noisy storefront in West Philadelphia, with people yelling, machines beeping, and metal clashing against metal in the background. A man with a dramatic handlebar moustache saluted our small group of nervous adults. The man had broad shoulders, and he was wearing black athletic tights and a bulky brown water-buffalo-leather jacket with black sleeves, so he looked like a tall and ominous gamekeeper, or the third assassin in a fight scene set in an unidentified Eastern European country. He had a weird quasi-Hungarian accent, even though he grew up in Detroit. He was our children’s fencing coach, Mark, and we had all signed up for his one-day class for parents.

He was teaching a parent class so that (so he said) we could understand what our kids were going through. We actually knew he was doing it to get the parents to stop giving their kids terrible advice, and to stop pestering the kids when they were fencing. Most of the other parents were taking the class so they could give their kids better terrible advice. I was taking it because I wanted to learn how to hit people. My kid Jess had been fencing several years by that point, and didn’t need (or want) any advice from me.

Mark took us seriously that day. He taught us how to do fencing footwork, which involves sort of half-sitting in mid-air with your feet in weird positions while moving back and forth, without bobbing up and down or sticking out your butt. After the footwork, he had us play games. Mark loved games. He had an elaborate curriculum, and liked to talk about his ideas at great length, while his students fidgeted and waited for him to finish talking. I was never very good at the games, which involved balls, gloves, frisbees, elastic cords, and all kinds of other paraphernalia. Also more footwork. A lot it. My quads and glutes were devastated. I was stiff for weeks after that class.

In the afternoon, once we were pale, sweaty, and haggard, Mark finally let us go up one by one against the club’s best epee fencer, Mary. I don’t think he dared have us try to hit each other, because someone would have gotten hurt. Mary was superbly competent, and none of the parents could manage to hit her, no matter what they did. She would step back slightly, or step in, or redirect their blades with her blade, or just poke them anywhere she felt like as they were coming towards her. She didn’t make a big deal of it. You just couldn’t ever hit her, and she always hit you. It didn’t hurt. It was just crushing.

I managed to hit Mary twice when it was finally my turn, though. I remember people laughing as I did it, because I looked awful doing it and because I was incredibly excited. It was wonderful. It was what I wanted to do.

I signed up for the adult beginner classes. I was the only parent who did.

Because I got results later on, people have frequently implied that must have been easy for me, and that I was a natural. Oh, no. For one thing, I have exercise asthma. Also, I am fairly constantly bewildered. Confusion is my natural state. I spent that whole first year of classes playing Mark’s games and never having a clue what I was doing, no matter how much he lectured. I used to go to the sidewalk out front of the club and say loudly to the dark evening sky, “I have no idea what you are talking about!” But then I would go back inside.

We started with about 12 adults in the beginner class, steadily lost people in the intermediate class, and ended up with three in the advanced class. I loved it, though.

I had a challenging job, a middle school kid, a husband who was starting his own business, and a mother who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease when I was the local daughter. I was trying to write my doctoral dissertation, and failing. I didn’t have much money. But for an hour a couple of times a week, I was doing something hard that was just for me, and I was getting to be some kind of competitive athlete. For that hour, I didn’t have to be someone’s mother, wife, daughter, or teacher. I didn’t have to think about grad school. I could just be a competitive athlete who was trying to trick someone so I could hit them.

After nearly a year, I finished my classes, and Mark told me to go to my first tournament, a novice event (for people who had been fencing less than a year). It was about an hour away, at a small club in a small town, and I brought Jess with me for moral support, because I was pretty sure I was going to be turned away. You see, in several years of taking my child to local, regional, and national tournaments, I had never seen any adults fencing in official competition, except for experienced athletes like Mary.

I was so scared my heart was pounding. I was sick to my stomach. I hated the whole thing, and I wanted to go home, but I went inside. I got Jess to take my picture, wearing fencing knickers I had ordered online. They were too big for me. I felt like a clown. I was also definitely the oldest competitor there. There was an eleven-year-old boy named Drew, and a buff-looking young man named Doug in sweatpants with “USMC” printed the leg, and some teenagers. But there were in fact a couple of other grownups. At any rate, no one turned me away.

That tournament was a genuine mess, and I wasn’t the only one who didn’t know what I was doing. That was heartening. I beat USMC Doug. And once, I made the referee laugh so hard she couldn’t keep going, because I just stuck out my point and my opponent, a grown adult named Noelle, marched forward and ran onto it. I ran the eleven-year-old off the end of the fencing strip several times too, because he didn’t seem to know how to go forward. I beat some other people, too. There were fourteen of us, and I finished fifth.

Some people never go to tournaments. They enjoy practice at the club, and they don’t want to compete. I get that. It’s pretty intense pitting yourself against other people one-on-one on the piste. Every tournament I went to after that first one, for thirty years, I was still scared someone would tell me to go home, that I didn’t belong. My heart always pounded. My stomach felt awful. I hated the world and everyone there. And yet I kept competing for thirty years, because it felt as if I was doing something just for me, and that seemed to matter more than anything else.

January 25, 2024

Pot Metal Memories

My hobby of the last few years has been getting rid of possessions I don’t need any more–clothing, furniture, household items, files, duplicate tools, crafts supplies, and mementoes.

Sentimental items are the hardest to release, but I was successful with most of mine. If I proceeded slowly, it was easy to go through old pictures (I scanned them and stuck the originals in albums), old letters (I re-read them, and scanned some), and a few objects from my childhood and from my family’s life (stored in a couple of tidy boxes in the basement, with lots of extra space in the boxes). I have two bound copies of my Ph.D. dissertation, a pile of my published books, and a small handful of other books that I will actually re-read at some point, but the rest were all given away. My basement is spacious and clear. I even have a spare room in my house with nothing in it at all.

One category has been genuinely hard to get rid of, though. It’s a collection of pot-metal flat objects in various shapes, fencing medals, from the sport I practiced from the early 90s to the early 20s (I retired last year). Because it was a small sport, and because they used to let me do it, I went all the events that would allow me to compete.

More or less by accident, I started fencing the discipline of women’s sabre when they started allowing women to do it, so at my first small events, I often came home with a medal. There might be three of us entered, but even if I finished last, by god I got a medal, and I was proud of it, because I didn’t start fencing until I was in my 40s and it felt like a real achievement to show up.

Then I kept getting better, even though I was getting older, and for a while I competed successfully in open events, even in international ones. When I got too old to defeat competent fifteen year olds, I switched entirely to over-50 age-group tournaments, and I competed in about fourteen world events for people my age. Most of the time, I came home with another medal, and sometimes, I even won.

That’s a lot of pot-metal.

The collection used to take up a lot more space, but a few years ago I started cutting the ribbons off and chucking the medals into a crate . The crate was too heavy to move easily, and they got dusty. A couple years back, I sorted the medals into two piles, and stored all the minor medals in the basement, keeping the ones I’m proudest of in a basket upstairs.

But there are too many medals.

The collection.

The collection.The thing about sentimental items is that they have stories attached to them, and my fencing journey was all about accumulating stories. I have competed against the best in the world, I have been to some very odd and interesting places, I have known all kinds of people who are important in the sport, and every time I competed, I was terribly afraid of losing and yet I showed up anyway. That counts for something.

I don’t want to keep all these little flat metal pieces. They have no intrinsic worth whatsoever. When organizers take a photo of the champions, and insist that they bite their medals, it’s because the medals are supposed to be gold, soft enough to show a tooth mark. But even Olympic gold medals are mostly silver nowadays, and if you bite them, you risk breaking a tooth. My medals wouldn’t get me a dollar at a scrap metal yard.

I should take the ones that really matter (the four laid out at the very far end) and put them in a shadow frame. I should chuck the rest.

But I want to keep the stories. I’m going to try to tell some of them. And then I can get rid of most of this load of cheap metal.

January 3, 2024

Never

When my little Sugar died last summer, my heart was broken because she was the best little cat in the world. Well-meaning friends offered me their extra cats and spare kittens, but I told my friends I was never getting another cat. I meant it, too, in the way I swore off boyfriends forever two weeks before I met my future husband. That is to say I really, really meant it.

No litter trays to scrape. No regular feedings. I could leave town on a whim for a week. No one to see through a full life that is far too short, and watch eyes dim and fur get lusterless and rumpled. No responsibility for deciding when they were to be eased out of life. No disproportionate grief. I was done with disproportionate grief, thank you very much, especially because my husband had died nine months before Sugar did.

Therefore, there was absolutely no reason for me to be scrolling an animal shelter’s web page three months after Sugar died. It was an accident. But then I saw a blurry photograph in the gallery, a picture of a big gray boy. His name was Louie, and he was apparently exactly the right kind of cat. I can tell a cat who loves people just by their eyes, and Louie had those eyes. Big, round, clear, a little baffled.

I had some time free and though I was absolutely not getting another cat ever, I got on a bus and went to the shelter, and there was Louie in a cage with another cat.

Yup, Louie’s eyes were just as advertised. He also weighed sixteen pounds, a great big pile of cat on a small frame, and he was huddled into the corner of the cage ignoring the other cat imprisoned with him. Apparently, he was skinnier than when he arrived, because he had not been eating while he was at the shelter. He had been surrendered with the other cat by a family who was moving and who couldn’t take them along. He was eight years old. He was sad.

I asked to look at him, and the attendant opened the cage. I reached my hand in. Louie licked it.

Oh. Apparently I was getting another cat. Or he was getting me. Either one. Both.

He was too heavy to put in their standard free cardboard carrier, because he would have gone through the bottom of it, so they loaned me a spare carrier, and I took him home on the bus. I stashed him in the bathroom to get acclimated, and after a couple of days when I let him out, he did the cat thing, which is to find the smallest possible space in which to hide and stare out like a damned soul looking out of hell. I spent a lot of time down on my hands and knees talking to a scared person with big eyes who was under an armchair.

A week after I got him, the shelter called me to tell me they had switched his name with the other cat in his cage, and he was actually named Hercules. That is complete nonsense. He is obviously a Louie, and Louie he remains. All one has to do is look at him. Louie.

I’ve had him for over three months now, and he has lived here forever. He plays with the toys I got him, and since he’s been on a diet, he actually leaps into the air when he chases the toys, at least a little bit of air. He still looks a little bit like an upholstered footstool, though. He’s got a big chest, a big round head, and a short tail, and he is a beautiful black-and-gray-striped tabby with a pale muzzle and soft paws.

Louie is not all that interested in food, not really, so the diet is easy. What he wants is (a) to be near me (b) to get petted (c) to play with mousie toys and (c) yeah, well, all right, food. But he doesn’t have a very good sense of smell, so he doesn’t come running when I open the can, and I have to show him the food. Either that, or he’s playing me. Either is possible.

He sleeps with me all night, though he leaves at least twice because he has to go downstairs to get his two stuffed shark toys (one trip per shark), which he brings up to me (wailing the whole way) and drops on the bed. I always thank him for the shark, even though the process wakes me up.

During the day, he comes where I am in the house and watches me. He’s not expecting much of anything, just watching me. He adores me. I am wonderful. I am God. I am going to do something worth seeing any moment now. Just my existence is enough, actually.

His utter concentration is unnerving. Sometimes I have to leave the house to go for a walk. My husband likewise wanted to be in the same room with me, and would come into my study and sit, even though he knew I didn’t like it, even though I asked him not to, so I used to leave the house sometimes then, too. It is very strange to be much loved, and to love someone else, when you are basically a grouchy introvert.

When I lie down for an afternoon nap, Louie jumps onto the bed, nestles into his official position under my arm with his paws resting on my chest, and permits me to scratch his chin and the top of his head until I pass out. When I wake up, he’s still there, and I am trapped because he will never move and it’s too wonderful. Eventually, he will start washing, and that is wonderful too, especially since he has lost enough weight that he can wash his back now. I lie there wondering why love keeps feeling so much like pain.

I am never getting another cat after this. And this time I mean it. Really. He’s asleep on the armchair next to my desk right now, breathing in and breathing out, and my current plan is that he is going to live forever, which will solve the problem completely.

January 2, 2024

Playing home

When I was a child, we played “paths” in the woods between my cousins’ house and my grandmother’s cottage out in the country. That is, we cleared away some of the dense thatch of maple leaves on the ground, creating a walkway between the skinny self-seeded saplings. Each of us children created a small space off the walkway for a home, decorating our “houses” with found bits of lumber, loose bricks, stones from the stream down the hill, and sticks stripped of bark. As neighbors in a community that smelled of turned earth, leaf litter, and peeled bark, we visited one another, admired each other’s decorating skills (my sister’s houses were particularly well put-together), and conducted an imaginary economy. It was like playing with dollhouses, except more like The Boxcar Children with their cracked teacup and their abandoned railway car.

Later, when I was fifteen, I yearned for my own home with a fierce misery beyond assuaging. My family lived in a very big house, and I had my own room, but I didn’t want our house, which was a miserable place. My mother did a very kind thing for my fifteenth birthday: she gave me a set of china plates, some flatware, two big aluminum pots, and two immense stainless steel kitchen spoons. I took it all with me when I moved into my own apartment much later on, and it wasn’t until this year that I finally gave away the last piece of the set, the enormous spoons, which I never actually used.

Eventually I became a sort of adult, married, and owned houses of my own, but I still dreamed of something else. I found that “something else” in New York City thirteen years ago. I was attending a workshop at Teachers College, with cheap lodgings in Union Theological Seminary. It was not a hotel room. American hotel rooms are oppressive, with vast beds, with monstrous televisions, and with bed linens that are ludicrously puffy, and heavy enough to smother. The room at the seminary was more like a European one, with low twin beds, cheap coverlets, a big window, a small refrigerator, and a few drawers. In that room in the city, I felt as if I was in heaven. I was by myself, free to leave and return whenever I wanted, and I could go out to a coffee shop or bookstore without having to tell anyone where I was going.

I carried away with me that image of a little room, furnished with small necessities, where I could be myself, by myself. Now I was happily married, with a grown kid and an interesting career, mind you, but I yearned for that imaginary space as I suppose some little girls yearn for a three-story Victorian dollhouse with wallpaper.

It wasn’t exactly the “tiny house” image that was captivating me. The tiny houses in the magazines and websites look cramped to me, and I could too easily envisage descending into clutter. No, my dream of a little house wasn’t about smallness. It was partly about being alone and independent, but it wasn’t entirely about that, either. I wasn’t sure what made it so compelling.

And then my husband fell ill. He had refused adamantly for years to get a colonoscopy, but finally went along when he was having too much gastric distress, and by then he had stage four colon cancer. The first year of his treatment was fine, but as he got sicker and sicker, the image of my “little house” kept returning like a fever dream. I took long walks, and as I walked, I imagined where I would buy my little house, and what I would do to it before I moved in. I painted its interior walls, had the floors stripped, hung curtains, and put potted plants in the back yard.

And then I would come home to my own real three-story row home with a hospital bed on its first floor, and with piles and piles of medical supplies everywhere, and with my increasingly smaller husband sitting propped up on his pillows, gaunt and a little confused, watching the Phillies get to the World Series and talking to his friends. I would dive back into the intolerable and oppressive tumult of being a caregiver.

When he died I got busy getting rid of everything in the house that I didn’t need any more. I kept taking things out for over a year, ejecting all the unnecessary inventory, the extra tools, the things I didn’t use and didn’t need. Apparently that was how I grieve. But when I finished decluttering, I kept going, because it turned out even when everything was organized and tidy, there was even more I didn’t need. I was thinking about my little house, and how I could fit into it, you see.

Last night, I was lying reading on my sofa with the cat tucked on the windowsill next to me, and I put my book down and looked around at my imperfect home. My kitchen, which the previous owner renovated hastily, has cracks in the tile, but contains all the food and dishes I actually need. The dining table is awkwardly positioned because the first floor is a strange shape; the half-bath we put in the first floor takes up too much space.

I got up and looked around the house, turning on the lights. My basement walls are crumbly, but the basement is dry and everything in it is something I am storing for a good reason. My clothes closet is only half full, and contains only clothes I actually wear. My bedroom has a bed in it, and a lamp, and a couple of nightstands. My third floor study is lined with mostly empty shelves, because I got rid of whatever I didn’t actually use, and the desk is cheap and battered. But in my childhood, I learned that a piece of scrap lumber makes a perfectly adequate bench, if you prop it on a few bricks and if you sit carefully.

My home isn’t perfect, but that little room in the seminary was far from perfect. I think what is making me so happy right now is that my actual home is completely provisional. It’s imaginary. It’s a clearing in the woods, it has everything I need, and I am pretending to live in it. If everything is temporary and imaginary, it turns out I have a most excellent life. I don’t think I need to move after all.