Peter Hitchens's Blog, page 329

July 13, 2011

A Different Sort of Bonfire Night

Northern Ireland is one of the most exotic destinations any mainland British person can visit. In some ways it is odder than North Korea or Burma, because there is no language barrier and one can see more easily what might otherwise be hidden.

I suspect it is also fairly unsettling for anyone from the Irish Republic (Dervla Murphy's interesting travelogue 'A Place Apart' certainly suggests that this is so). I always enjoy going there for many reasons. There's the almost invariable friendliness and good manners, the beautiful landscape, the endless surprises, the old-fashioned homeliness reminiscent of a seaside resort half a century ago , such as a café on a Belfast Street called (quite typically) 'Rumbley Tums'.

Much of it is unglobalised, as the world of the shopping mall and the supermarket was kept away by the Troubles and only arrived a few years ago, so many small shops and cafes are still (just) hanging on, though I fear the place will be as cloned as everywhere else before too long.

And then there are the other things. There's the ever-interesting puzzle. Am I in a Protestant or a Roman Catholic part of town or countryside? And there's the fascination of the only land border possessed by our mainly island nation. I love borders, because we don't have any (except in Ireland) they are places where ideas solidify into material things. You can walk 100 yards and be in a different world thanks entirely to human will. Now that the Iron Curtain has gone, my favourite frontiers are the Franco-German one at Strasbourg/Kehl, which you can walk across without any ceremony but which still divides two utterly different countries; the US-Mexico border (at El Paso/Juarez or San Diego/Tijuana) where you can look across a narrow river from the first world into the third; the Czech-German, between Dresden and Prague on the banks of the Elbe, which tells you what the new border-free Europe really means; the border of all borders, the astonishing Panmunjom crossing (or rather, non-crossing) between North Korea and South Korea, which I have now visited from both sides. There's also the linguistic border between French-speaking Wallonia in Belgium, and Flemish-speaking Flanders, so much more visible than the political border between Flanders and the Netherlands a little further north.

As for the border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, it is a ghostly thing, very much present in the midst of all who live there, but generally impossible to spot without a very good map. Even at the height of the Troubles, I once crossed it by bicycle without knowing I had done so. And when I cross it on the wonderful train that runs between Dublin and Belfast (and could there be two more contrasting destinations in the world so physically close to each other, so easily reached from each other (and now only 90 minutes apart on expensive new roads – though why some of that money can't be spent on rebuilding Ireland's badly-neglected railways I don't know). I can never make up my mind where the division runs. Was that an Irish numberplate? Is that farm in the Republic? Or that pub? How do you tell, especially since the Republic got so prosperous under the EU? Even flags, especially flags, are not necessarily a guide. There are plenty of Irish tricolours in the north (though precious few Union Flags in the south).

So when I was asked over to Belfast to take part in the BBC's 'Sunday Morning Live''(still available on i-player, subjects discussed, the Murdoch affair, church schools and (very briefly) the route of future corteges of service personnel killed abroad) I asked them to book my homeward flight on Monday, so that I didn't have to rush off and could take a small wander around the province while it is still, formally, part of the United Kingdom.

The last time I had a similar chance, I slipped over to Londonderry on the beautiful railway line that runs round the north coast, and returned to Belfast on the bus that runs through the glorious Sperrin Mountains. On the return trip I saw a lot of evidence of Sinn Fein's strength, in the form of posters and symbols in village streets.

This time I headed off on Sunday morning to a place I had long wanted to visit, the Cathedral City of Armagh. Armagh has two cathedrals, both dedicated to St Patrick. One is now the heritage of the Church of Ireland, the local version of Anglicanism, but disestablished and significantly different from the Church of England. For instance, in its churches north of the border there are prayers for the Queen, and , in the South, for President and Dail. Yet, thanks to its former status, it possesses two (yes two, Christ Church and St Patrick's and Christ Church) great cathedrals in largely Roman Catholic Dublin, plus the commanding St Columb's in Londonderry (where Bishop Alexander's beautiful wife Frances wrote 'All Things Bright and Beautiful' and a fine St Patrick's Day hymn as well) and the ancient site in Armagh, both on hilltops.

But first I must get to Armagh. I took the slow, stopping bus from Belfast and was glad I had. The province was acutely conscious of the approach of 'The Twelfth' , 12th July, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 which Protestants still celebrate as the moment of their triumph over Roman Catholicism.

Most mainland people have forgotten, if they ever knew, about those decisive times. Few (alas) read Macaulay's thrilling 'History of England;' with its account of what he saw (and I'm inclined to agree with him) as the refoundation of our liberty on a sound basis. For 1689 is the date of our Bill of Rights from which that liberty flows. In Ireland it also meant the Protestant Ascendancy, penal laws and cruel discrimination against Roman Catholics which hindsight suggests were stupid as well as nasty and plain wrong. The English, Scots, Welsh and Irish ( and Cornish for that matter, given my own ancestry) all have far more in common with each other than they do with the various French, Spanish and German governments which have tried to turn us against each other. Perhaps if we had tried a little harder we might now not be suffering the national break-up, sponsored by the EU, of 'devolution'. Nor would the unending bitterness left by the 1916 rising and the execution of its leaders still lie between the British and the Irish, with sad effects for both.

You have to think about this as the bus wanders through Lisburn, Lurgan, Moira, Craigavon and Portadown. In most of these places there is clear evidence that Unionism and the Orange Order are still very much alive and not likely to lie down happily if the province is switched ( as may well happen soon) to Irish rule.

Main streets and housing estates are alive with red-white-and-blue bunting. Ceremonial arches bearing the mysterious symbols of the Orange Order (what do the coffins mean?) stand over main streets and in some villages and housing estates I note that in many places the Scottish Saltire flies alongside the Union Flag and various Ulster banners – does this development, new to me, mean that Ulster's Protestants with their Scottish ancestry, are pondering a breakaway from a breakaway if Northern Ireland votes for Dublin rule when the long-promised referendum comes?

I had been primed for all this by my sight on Saturday night of a towering 60-foot bonfire in Belfast's Mount Vernon. And when I say towering, I mean it. This is not a ramshackle conical Guy Fawkes-type heap of logs and branches and old chairs. It is much more serious . It is a hard, stark square, dark tower, perhaps ten or 12 feet broad, made of pallets. It is guarded by sullen urchins, maintaining a votive fire of old car tyres guaranteed to produce a plentiful supply of sinister black smoke, the sort that hangs over cities in 'palls' (why 'palls'?) If this isn't a dead metaphor I don't know what is. Most people don't know what a 'pall' is and have never seen one. So they think it's a synonym for 'cloud'.)

Confusingly for the outsider, this structure is topped by two brand-new Irish Tricolours - green, white and gold. They are only there to be burned. In another part of Belfast I saw a bonfire actually built on a patch of sand on the street, which featured a Palestinian flag, set for burning. In a nearby housing estate a couple of houses few the Israeli flag. Protestants have identified with Israel, and Roman Catholics with the Palestinians, in some curious way that makes only partial sense. Best not to think about it too hard. In a way, it is quite funny.

At first glance, Armagh City is untouched by this battle. Much of it is close to paradise. There's a beautiful green swathe through the centre of the small city, flanked by elegant houses, many faced in that lead-coloured stone which gives older Irish towns that strange, long-ago wistful look they have. But it's obviously a Protestant swathe. There are two war memorials on it, these days always associated with British wars. From a (Protestant and obviously English-influenced) Church tower above, the bells can be heard playing the tune of that old Anglican hymn by George Herbert, 'Let all the world in every corner sing , My God and King!'

At one end is an extraordinarily handsome court house from the age of William Hogarth, in that austere and rather cruel style of building that makes you expect to see red-coated soldiers, men in wigs and breeches, and a cart containing a couple of condemned men on their way to the gallows, come trundling round the corner. At the other end is a semi-derelict prison in the same style - once again very handsome, and also coldly ruthless in its unyielding message of power and ascendancy.

On a small hill over the city, not much larger than most English parish churches ( and smaller than some I know) stands the Church of Ireland cathedral, very English inside with its battle flags and florid tombs, though plainly nothing like as rich as any English cathedral.

A short walk through the centre (some of it beautifully maintained, yet some of the fine buildings neglected and almost derelict) takes you to another hill, where the Roman Catholic St Patrick's stands at the top of an impressive flight of steps. This is a severe Gothic structure outside, unmistakably Victorian. Inside it is as gorgeously decorated and colourful as its Protestant sister church is plain and subfusc.

But I had the feeling that both of them stood above a conflict that had little to do with religion any more, and much more to do with territory, a gathering contest to show who's boss, and the fear of loss.

It didn't take me long to find the 12th July bonfire waiting for its moment of ignition in an obviously Protestant estate (plenty of flags and bunting) on the eastern side of town (no Tricolours were on top of this more modest structure, I am glad to say. Celebrating your own heritage is one thing. Scorning your neighbour's is another) .

And it didn't take me much longer to find Tricolours hung in earnest, and very high up, on the lamp-posts flanking the big Friary Road, which fringes the southern edges of Armagh and runs past the main Roman Catholic district. I wasn't much surprised to read on Wednesday that there had been trouble on this stretch on the Twelfth. Much of the trouble seems to have come from Nationalist protests *against* Unionist marches and celebrations.

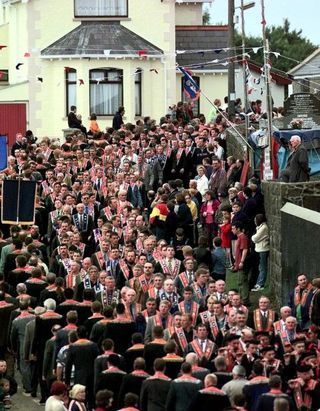

By great good fortune I saw an actual Orange parade. As I strolled past the Courthouse on Sunday evening, I noticed police gathering on motorbikes, neutrality made easier by the crash helmets obscuring their faces. Then, out of the fine classical portico of a building whose inscription identified it as the 'Scotch Presbyterian Church' (built 1837) I saw them coming, the legendary figures in their bowlers, hats, even a couple of Orangewomen in orange collarettes bearing silver lodge numbers. But not, absolutely not, bowler hats (they disappeared later, perhaps to make sandwiches, and didn't go on the march) . There was a pipe band. There was a big Lambeg drum and some smaller rattlier ones. There was one woman piper and an austere young woman leading the kilted pipers. There were men, dressed a bit like Royal Navy petty officers, playing flutes. One of these stepped out of the parade to shake my hand, which I rather liked. They had old-fashioned faces, faces from a world where fathers are heads of families, Sunday is for church, work is hard and duty strong, which is the main reason why mainland left-wingers (who couldn't really care less about Ireland in my view) don't like Ulster Protestants. And it is also why Ulster Protestants have such bad Public Relations in modern Britain.

They struck up 'Abide with Me' (though they quickly switched to other tunes that I do not know but suspect of being more Orange and less Christian) , and set off round the town. I love a good parade, and followed them for the enjoyment of the thing and to see what might happen. The streets were mainly empty, it being around 7.30 pm, when even in Northern Ireland people watch the TV. There was hardly anyone there, and nobody had come along to be offended or provoked. A few teenagers outside a pub whooped and squealed mockingly. The scene was as baffling to them as it would have been to their equivalents in Leeds or Southampton. It had a sad feeling to me, as of shouts heard from a long way off, or half-remembered music from a summer evening a long time ago.

The next morning I took the early bus to Newry, last British town before the border, and strolled up to the sparkling new railway station on the hill, past a smart marble memorial to an IRA volunteer (the stone says in two languages that he was 'murdered' by the British Army, and surmounted b y a tall flagpole adorned by a tricolour). In the Union-Jack-free town centre, with its Gaelic Athletic Association notices in the friendly coffee bar and its huge old-fashioned butchers' shops catering to big families, if I hadn't known for sure I was under the Union Flag I'd have thought I was in the Republic. It was only on the way to the station that the 'Real IRA' graffiti ('PSNI, RUC, different name, same aim') and the IRA man's memorial made it clear where we were. The station itself had a neat bilingual stone commemorating its recent opening. Then the smart grey and green train came roaring in from Dublin, bound for Belfast, sweeping me away from the Mountains of Mourne and the IRA monuments and back to what passes for normality.

July 11, 2011

The 'Anti-Depressant' Controversy again

Today I turn to a different sort of drug – this time a fully legal and respectable sort. I will no doubt re-engage soon with Mr Wilkinson on cannabis, but think this is more pressing and also that what follows is rather exciting, if , like me, you are excited to see dissent from conventional wisdom championed by a clear, scientifically trained mind, in limpid prose.

A friend has alerted me to two powerful and refreshing articles in the New York Review of Books on the huge and urgent topic of antidepressant drugs, about which regular readers know I am greatly concerned. Both can be found on the web. Both are by Marcia Angell.

The first (to be found here) is entitled 'the Epidemic of Mental Illness: Why'. The second (to be found here) is called 'The Illusions of Psychiatry'. Or you can buy the magazine, which should be encouraged for publishing articles of this calibre.

Marcia Angell is a qualified doctor and was the first woman to edit the highly reputable new England Journal of Medicine. She now lectures at Harvard Medical School. I don't think she or her argument can be lightly dismissed.

Her articles are reviews of four books ('The Emperor's New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth' by Irving Kirsch; 'Anatomy of an Epidemic: magic Bullets, Psychiatric  Drugs, and the astonishing rise of Mental Illness in America' by Robert Whitaker ; 'Unhinged: the Trouble with Psychiatry – a Doctor's Revelations about a Profession in Crisis' by Daniel Carlat; and the American Psychiatric Association's 'Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders', Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)'.

Drugs, and the astonishing rise of Mental Illness in America' by Robert Whitaker ; 'Unhinged: the Trouble with Psychiatry – a Doctor's Revelations about a Profession in Crisis' by Daniel Carlat; and the American Psychiatric Association's 'Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders', Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)'.

I have not yet read any of these books myself, though I hope to do so . I think we can trust Dr Angell to have given a fair account of them.

Using them as her foundation, she charts the revolution in Psychiatric treatment, which has shifted almost entirely from Freudian therapy to the prescription of drugs in a very short time. She notes the huge increase in categories of mental illness, and the matching increases in the numbers diagnosed with them.

She asks :'What is going on here? Is the prevalence of mental illness really that high and still climbing? Particularly if these disorders are biologically determined and not a result of environmental influences, is it plausible to suppose that such an increase is real? Or are we learning to recognise and diagnose mental disorders that were always there?

'On the other hand, are web simply expanding the criteria for mental illness so that nearly everyone has one? And what about the drugs that are the mainstay of treatment? Do they work? If they do, shouldn't we expect the prevalence of mental illness to be declining, not rising?'

Now, I agree with all these questions, and if I asked them I would be angrily pelted with slime by supporters of the 'antidepressant' culture. But this isn't me. And it's based on several reputable books by qualified experts.

I can't urge you strongly enough to read the whole thing for yourself, both parts.

But I will leave you with one profound thought arising from these cogent and tightly-packed reviews to which I think we need an urgent answer. She notes that the great discovery of science in this area was that 'psychoactive drugs affect neurotransmitter levels in the brain, as evidenced mainly by the levels of their breakdown products in the spinal fluid.'

Then ' the theory arose that the cause of mental illness is an abnormality in the brain's concentration of these chemicals that is specifically countered by the appropriate drug'. She gives examples.

She adds (devastatingly in my view) 'Thus, instead of developing a drug to treat an abnormality, an abnormality was postulated to fit a drug'.

I will repeat that because it is so important : 'An abnormality was postulated to fit a drug.'

That, she says, was a great leap in logic. It was 'entirely possible that drugs that affected neurotransmitter levels could relieve symptoms even if neurotransmitters had nothing to do with the illness in the first place'.

On the logic used to justify these drugs, 'one could argue that fevers are caused by too little aspirin'.

Now, what follows is my view, not Dr Angell's . If these drugs (which undoubtedly do act powerfully on the brains of those who take them) are being prescribed on this guesswork basis, isn't is possible that they may in fact affect the brains of otherwise healthy people in unpredictable and unintended ways?

And is it possible that they are now such a large industry that doubts of this kind are unwelcome?

I do urge those interested to drink deeply at this particular spring. When you have done so, I would like to renew the argument (which is also relevant to the mass prescription of drugs to children alleged to suffer from 'ADHD') .

July 9, 2011

Politicians want Fleet Street to be tamed... you need to ask why

This is Peter Hitchens' Mail on Sunday column

When the hacking row is over, will the right people be punished? I doubt it. As with the MPs' expenses scandal, the most prominent offenders will almost certainly get away with it, while a few expendable figures will be cast into prison or otherwise ruined.

There is another worrying parallel with what happened to MPs, who are now pitiful serfs of the state, barely trusted to sneeze without approval. These sordid events will be used as the excuse to bring in new rules that destroy the independence of the Press.

There is another worrying parallel with what happened to MPs, who are now pitiful serfs of the state, barely trusted to sneeze without approval. These sordid events will be used as the excuse to bring in new rules that destroy the independence of the Press.

You may think that Fleet Street needs to be tamed. But once it has been, you will be sorry. For no other force in our society is so good at exposing and restraining the corruption of power.

To be able to do so, it must be free. To be free, it must be independent. To be independent, it must be commercially suc¬cessful. To be commercially successful, it must appeal to a large audience. To appeal to that audience, it must to some extent follow public taste.

And public taste has got worse as our schools and morals have declined. It would make you weep to look at the mass-circulation popular newspapers of 50 years ago, because of the

far higher levels of taste and education they rightly assumed their readers had.

Much of the rage against the Press is actually the anger of people who are a little ashamed of the things they secretly enjoy. High-minded news¬papers (like the old Sun before Rupert Murdoch took it over) are seldom popular. Unpopular papers rarely make money and are often subsidised by their popular stablemates.

Now, when I came into this trade I did not think that I was joining the Sisters of Mercy. I had watched films such as The Front Page and Ace In The Hole. I had read Evelyn Waugh's Scoop and realised that its depiction of Fleet Street, with all its megalomania, was largely true. I knew that Lord Beaverbrook hadn't been a nice man.

I knew that the job sometimes involved a little subterfuge and ruthlessness.

But I also knew, deep down, that this country's unique Press was all the better for being big and rough. The main threat to our freedom, and the main threat of corruption and injustice, came from the state.

I took to heart Thomas Jefferson's great declaration that he'd rather have newspapers without a government than a government without newspapers. For Jefferson, having been President of the USA and a journalist, knew from within the temptations of power and the need to restrain them. He understood that governments can never, ever be trusted.

And I hope that during my career I have managed to annoy, upset and inconvenience one or two politicians. If I hadn't, I wouldn't have been doing my job.

So when you listen to politicians calling for more regu¬lation of the Press, beware. They are really calling for less regulation of themselves.

The truth about our hidden war dead

Here's the truth about the Government's decision to route the hearses of soldiers killed in its various stupid wars away from any of the nation's High Streets.

This comes into effect very soon, when the bodies of the dead start to arrive at RAF Brize Norton, next to the Oxfordshire town of Carterton.

Junior Defence Minister Andrew Robathan stumbled a bit trying to deal with this in Parliament on Monday.

First, he disclosed that the back gate of the RAF base, through which the hearses will pass, is to be renamed the Britannia Gate. Who thinks of these things? The Downing Street cat?

Were I to rename the back door of my house the Britannia Door, it would still be the back door.

Then he said that the route through Carterton was unsuitable for corteges because it has speed bumps. So does the bypass route that the processions will actually take, as Mr Robathan ought to know.

He added that Carterton's streets were 'very narrow'. I doubt that they are narrower than those of Wootton Bassett, and plan to check them myself, unless anyone has measurements to hand.

But he was rescued from his confusion by a fellow Unconservative, the North Wiltshire MP James Gray.

Mr Gray asked: 'Does the Minister agree that it might not be possible, nor indeed quite right, to seek to replicate the Wootton Bassett effect elsewhere, as that was a chapter in our history? I am not sure we necessarily want to see it repeated elsewhere.'

Mr Robathan eagerly responded, saying Mr Gray had made 'a very good point'. Really? What was so good about it? I wonder who Mr Gray means when he says that 'we' do not want to see Wootton Bassett's spontaneous, unofficial, genuine expression of respect for courage, discipline and loyalty to be repeated.

He certainly doesn't speak for me.

Finally, a glimpse of the real JFK

Why are many TV critics so rude about the mini-series on the Kennedy family, now approaching its end on BBC2? It's far more honest about them than anything else I've ever seen on mainstream TV, and Tom Wilkinson's portrayal of the monstrous patriarch and crook Joe Kennedy is superb. It isn't Shakespeare, and isn't meant to be, but it's a fast-moving, concise account of a thrilling era and I can't stop watching it, whereas most TV these days sends me to sleep. Perhaps it's the honesty the critics don't like.

JFK-worship is still all too common among our media classes. The family's gangster connections, JFK's appalling infidelity, the sinister Doctor Feelgood pumping the President and Jackie full of drugs, the horror story of the President's lobotomised sister – and the towering figure of evil that was Joe – don't quite fit the picture. But it's all true.

Generation that hijacked Britain

Having myself been (rightly) watched by MI5 during a mis-spent Trotskyist youth, I was interested to ¬discover that the present Archbishop of Canterbury Dr Rowan Williams had the same experience, thanks to a close association with a group of Marxist revolutionary churchmen in the early Seventies.

I was also puzzled that this revelation attracted so little notice. Yet on the very morning the story appeared in the Press, the reliably Leftish BBC Radio 4 Sunday programme had its own version of the affair. This made the group sound all very jolly and harmless, despite being infested with open revolutionaries.

But it backfired slightly when its veteran leader, the Rev Dr Ken Leech, said of the Primate of all England: 'I don't think he has changed his politics over the years.' He was more or less the same as he had been in 1975, Mr Leech added.

No doubt this is true, not just of the Archbishop but of many others who were students in those years and are now MPs, senior civil servants, BBC moguls, judges, police officers, newspaper editors, teachers, professors, Tory Cabinet Ministers, you name it.

It's the great unspoken secret about this generation that, far from being absorbed by the conservative -British establishment, they absorbed it.

July 7, 2011

Where's the evidence?

A further chunk of responses to Mr Wilkinson.

Mr Wilkinson quotes me: 'In the case of cannabis and other illegal drugs, it is still quite possible, through enforcement, to discourage all but the most determined from taking up the use of drugs which are not part of our culture and which are widely (and justly) viewed with suspicion. For that, possession must remain an offence and be effectively prosecuted.

By the way, I really do hope those posting here who continue to deny the possibility of a link between cannabis and mental illness will soon grow up and start acting responsibly. Don't they realise that some young person, acting on their complacent, ill-informed advice, might end up needlessly in a locked ward? And it will be their fault. Can they really not face the infinitesimally small risk of prosecution, and the still smaller one of actual punishment, as the price of their nasty pleasure? In that case, are they really the bold revolutionaries they imagine themselves to be? Must they sacrifice others for it? And how long will they continue to expect that the rest of us will take their insistence that 'it never did me any harm' at face value? As I've pointed out before, they're not the ones to say. The self-regard of these people is limitless, and is perhaps a sign of the deeper damage done by this drug even to those who appear superficially to be unharmed by it.'

And he replies: 'I can't agree with this: the reason given for extending much harsher penalties to a substantial proportion of the population is that cannabis is 'not part of the culture' and 'widely (and justly) viewed with suspicion'. The justice of the suspicion is treated as an afterthought, despite being the important point.'

**My comment: This is silly. He should not read too much into word order. It is my view that cannabis is an evil poison that should be banned from sale by law because of the terrible things that it can do and has done to gullible and ill-informed people. That is why we are having this discussion.

Mr Wilkinson: 'If cannabis use is so harmful that we must attempt to stamp it out by the use of harsh penalties and vastly expanded detection efforts, rather than bringing it under regulatory control by legalisation, one would expect to be able to find good evidence of such extreme harmfulness (assuming that we are willing to accept that extreme social engineering should be brought to bear in any case).'

**My reply: 'Would we, though? How is such evidence obtained? Through research. Who will do such research? Those who are paid to do it. What are the sources of money for research which will explore the apparent correlations between cannabis and mental illness? In whose interest, in government or in commerce, would it be?

There seem to me, however, to be pointers. Some posters on this site attest to their own experiences. Patrick and Henry Cockburn's book suggests that there is a connection. My own acquaintance, and my rather wider correspondence with readers attest to numbers of parents (and teachers) who have seen young men (it is usually young men) go through severe mental health problems after the use of cannabis. Unless Mr Wilkinson is a hermit, and knows no parents of male teenagers, I would be amazed if he has not heard of such things. It is a very common story in modern Britain. The absence of research so conclusive as to persuade cannabis advocates doesn't in any way allay the suspicions aroused by such things. For how many tyears Mr Wilkinson even seems (I am not sure about this) to dismiss the work of Professor Sir Robin Murray as of no account. This seems cavalier, nonchalant, even arrogant.

The headline of my first reply was a quotation from Oliver Cromwell, in another context (and a play on the name of Mr Wilkinson's weblog, 'Surely Some Mistake'). What Cromwell said was: 'I beseech ye, in the bowels of Christ, to think it possible that ye may be mistaken.'

To the complacent army of the cannabis lobby, I suggest that this is actually quite a modest request. Not to admit that you are mistaken. Just to think it possible that you might be. Try it. On this matter it may save you from some regret when the research finally comes in. You have so much more to lose, from being wrong, than I have. If I manage to prevent a hundred young men (and their parents) from suffering what Henry Cockburn suffered (and will suffer till his life's end), then it will weigh in the balance quite heavily against many of the bad things In have done. If I turn out to be wrong, and Henry's trouble had nothing to do with Cannabis (unlikely, but there), then I will have done no harm to anyone by preventing a hundred young men from using a stupid drug. Now, try that the other way round.

This cannot go further until Mr Wilkinson answers my earlier question. I repeat it, once again: 'I want to know precisely which claims he views as 'overblown', and whether he accepts that cannabis has – or might in future be found to have - any dangers for those who use it. And if so, what he believes those dangers are.'

Mr Wilkinson goes on to deal with the morality of stupefaction. He says: 'That it is morally wrong does not of course entail that it should be subject to criminal sanction. The hoary example of adultery will do for one.'

**I reply: Yes, that's an example of a moral wrong that can't or won't be dealt with by criminal sanction.

But then again there are plenty of others, theft, violence, fraud, rape, that are morally wrong but can be and are dealt with by penal sanctions. So the distinction is unhelpful. Sometimes you can. Sometimes you can't. Sometimes you should. Sometimes you shouldn't. The decision appears to be pragmatic, as is most law-making. Will it work in this case? Yes, it will.

The need for the criminal law in this case arises from the very strong advertising of dangerous drugs as harmless and benevolent by the behaviour, song lyrics, statements etc of public figures, especially rock stars, but also painters, actors, scientists, authors, retired policemen, judges and politicians, broadcasters, poets etc, who have (in most cases knowing no more about it than I do and perhaps less) put their names to advertisements, reports and declarations claiming that the drug is harmless and calling for legal sanctions against it to be weakened.

Mr Wilkinson continues: 'Further, the claim that it is morally wrong in itself – rather than when done in some specifically irresponsible way such as when driving or in charge of children - is a hard one to justify.

** No it isn't. A substance which has (or which may reasonably be supposed to have) the unpredictable power to destroy the mind of any user even with moderate use, and which is on common sale and effectively decriminalised cannot be driven back into the margins of society if it is a little bit legal. Its sale and possession have to be unequivocally banned and systematically and predictable punished by law. Those who believe that it does them no harm (even though they are in no position to know, and even their closest friends and relatives cannot know what they might have been had they never taken this substance) just have to accept that for the greater good and safety of those weaker than themselves, the law is necessary. And they must therefore abide by it or accept the known penalties for breaking it. What they cannot morally do is insist that it should be on free sale to people who may be harmed by it, so as to make their own pleasure more convenient.

Mr Wilkinson here shows signs of exasperated superiority at my pigheaded stupidity. He sighs : 'I confess to not really knowing where to start in rebutting thus argument – it just seems obvious to me that this isn't the case, and that's not going to convince anyone who disagrees with me. I suppose I would say the burden of proof, as with regard to the need for prohibition, lies on those who make the claim.'

** My reply: This is slippery. Mr Wilkinson has the sense to know that the question has at least been raised about the safety of cannabis, and raised by serious persons. He has the historical knowledge to know that there was a long period during which tobacco had a similar status, and its users and promoters used similar arguments against restrictions on it (I have a 1963 volume of 'Punch' magazine containing lots of jokes about the laughable idea of the prohibition of cigarettes, which now looks a little lame). Richard Doll had a long fight to get official backing. I believe we are now in an equivalent period for cannabis (and for several legal drugs now in alarmingly common use). If my fears are shown, by serious research, to be groundless, then I shall abandon my campaign. But I don't think I shall, and I don't think Mr Wilkinson really thinks so either.

Mr Wilkinson returns to philosophy: 'But certainly Peter Geach – an eminent philosopher who has examined the issue in depth from a traditionalist, Christian perspective - concludes in The Virtues that such a case can't be made out – a view shared by his wife Elizabeth Anscombe:

p133:

If drinking alcohol is wrong, the reason is not that it makes you less alert than you might possibly be, but that makes you less alert than you then and there ought to be; and the degree to which you ought to be alert varies very much… a man safe tucked up in bed has no duty for even the lowest degree of alertness, for he could lawfully just go to sleep. There are mediate cases, into the casuistry of which I will not enter.

If we may for the moment abstract from the question whether the law-breaking that may be involved is morally objectionable, then we ought, I think, to judge about cannabis indica much as we judge about alcohol…'

**I can hear the high-pitched North Oxford giggles as this stuff streamed from the pen. 'Cannabis indica' eh? How jolly scholarly. Yet it is so easy to explode it. What if the man, having gone to sleep drunk, is woken at two a.m. by the screams of his children, trapped in a fire? Or not woken? Or not woken until far too late? Where then is his duty? Was the drinking or the (tee hee) consumption of 'cannabis indica' morally objectionable if the children, as a result, were not saved? Yet he could not have known the house would catch fire -only that there was a remote chance that it might. And a remote chance that he would be too stupefied to act with courage and decision. Even if he was alone and therefore (according to the utilitarian 'libertarians') nobody's concern but his own, he would have been more likely to burn to death, and others would have had to turn out to scrape through the ruins for his charred bones, or even risk their lives trying to rescue his already lifeless body. If a 'traditional, Christian perspective' gets you off that hook, then I don't share it.

As for the rest, I think it mere repetition. I'd rather have a stern law than freely-available cannabis, and I am quite prepared to accept the consequences. This of course makes me unpopular and disliked simply for saying so, and impels people to call me rude names. So be it.

This distinguishes me from my opponent, who maintains that there are no bad consequences arising from his policy, and would - so far as I can see - deny the dangers of cannabis until and unless they affected him personally (I beg him not to wait). I don't mind being called 'paternalist', as I think drug-takers are largely infantilised by their pitiable habit, and need a parental hand.

My reply is now concluded.

July 6, 2011

Depraved new world

In my argument with Tim Wilkinson, I had hoped to have a different sort of debate about drugs from the ones we've had here before (in which it became clear that the fundamental division was a moral one) and I still do hope so. Both sides, it seems to me, must be prepared to pay a price for their desires. Mine is clear – the harsh legal punishment of drug users.

In my argument with Tim Wilkinson, I had hoped to have a different sort of debate about drugs from the ones we've had here before (in which it became clear that the fundamental division was a moral one) and I still do hope so. Both sides, it seems to me, must be prepared to pay a price for their desires. Mine is clear – the harsh legal punishment of drug users.

But what about the legalisers? What will be the entry price for their paradise?

Two points arise:

I am slightly disappointed (I'm still working on responses to the rest of his post) that Mr Wilkinson has yet to reply (as far as I have seen) to my request which I here repeat. I'm not prepared to enter the argument about the dangers of cannabis until I have his response. My apologies if I've missed his reply. Can he in that case repeat it?

Here's the repeated request: 'Mr Wilkinson continues: "Overblown claims about the dangers are rightly seen as ridiculous by those who know anything about it."

**This is the most problematic statement in his argument so far.

It is perhaps the most important point on which both sides must work with the same material. I want to know precisely which claims he views as 'overblown', and whether he accepts that cannabis has – or might in future be found to have - any dangers for those who use it. And if so, what he believes those dangers are.'

I'd also express some disappointment in the failure of a vital part of this discussion to catch light. Pro-legalisation spokesmen often suggest that there's something anti-liberty about those of us who want the law on drugs enforced, as if smoking dope were the equivalent of free speech.

On the contrary, I believe a drugged society is likely to be a complacent society and a softly totalitarian one, as predicted in 'Brave New World'. (Eric Hobsbawm has remarked correctly that there's no connection in history between the liberty to enjoy pleasures the liberty of the mind. Rather the contrary. Slaves were often allowed to breed more slaves, but not permitted to marry and form permanent families)

I was recently shown the following passage by John Cornwell (in 'Powers of Darkness, Powers of Light, Viking, London 1991, p.18). It records an interesting statement by Freddie Ayer, the logical positivist philosopher and cheerful atheist.

Cornwell recalls (from a dinner at which they were both present in New York City some years ago): '"I have a problem" he [Ayer] said suddenly. "I don't accept the notion of public morality , so I would be logically encouraged to accept Huxley's Brave New World: the idea of us all taking happy drugs. Life, after all, comes down to our needs and their fulfilment, and provided one does not offend against another – why not do anything you want? My problem is this : I can see this argument intellectually, but I know in an instinctive way that Huxley's vision is wrong"'

I suspect that what worried him was that any thinking person must find Huxley's mindless, history-less, dissent-free, hideously calm dystopia repulsive. Yet it is also the logical consequence of permitting self-stupefaction as a general act. I think it should worry all advocates of legalised drugs.

I'm still working on replies to the remaining parts of Mr Wilkinson's original article, and will post them in due time.

July 5, 2011

Prohibition blues

Here's my second response to Mr Wilkinson.

Mr Wilkinson quotes me as saying: 'The ban on displaying cigarettes in shops will cause fewer people to smoke, as all the other measures have since the first health warning appeared on the first packet. And in time this strange, self-destructive habit, which is actually very new and only really invaded the civilised world during two disastrous wars, will be banished to the margins of life.'

He then says: 'But this is not prohibition – it is regulation. A legalised cannabis would surely face the same – or stronger – restrictions.'

**I won't quibble about definitions. But it seems to mean that the laws on tobacco in Britain are travelling towards prohibition, and have been quite cunningly drafted. This is what I like about them. They are incremental and effective. In time we will be able to move towards restrictions of distribution and sale which will drive cigarette smoking to the very margins of society and (in time) render it a strange and incomprehensible memory. I have no doubt that this is what is intended. But of course smoking cigarettes was until very recently socially, culturally and legally acceptable (my prep-school teachers smoked in class. Joan Bakewell smoked on live TV, etc), so its prohibition by a single step would be self-defeating.

In a reverse parallel, the legalisation of cannabis could not have been achieved in a single step. It had to be made culturally and morally acceptable first. That has been the job of people like Mr Wilkinson, and almost the entire rock business, and very good they have been at it, too.

The onus is on the owner or manager of the premises to enforce the ban. As he says, a similar burden on the owners of premises where cannabis was smoked was abolished by the 1972 Misuse of Drugs Act. This was one of several measures in that interesting Act which came very close indeed to legalising cannabis without most people noticing.

Mr Wilkinson says: 'And that would, on the parallel used here, lead to its use being 'banished to the margins of life'. Prohibition – especially the thoroughgoing, stamp-it-out prohibition that is apparently required - is a very different matter, with criminal records, prison sentences (which impact on family of course) and a vastly expanded police operation.'

**I am not sure where this definition of 'prohibition' comes from. US Alcohol Prohibition never punished possession or consumption – in my view one of several reasons why it had no chance of succeeding.

But cigarette smoking is rapidly becoming so unacceptable among the educated that I doubt that we shall need to adopt such penalties. Once its general sale is prevented, which must be the next major step, I suspect it will gradually die out in the advanced world. There really never was any good reason to smoke cigarettes, and most people who do it wish they had never started. It was only the stresses and privations of wartime which made it popular.

Mr Wilkinson continues (quoting me): 'Then we will have proof prohibition does sometimes work, if it is intelligently and persistently imposed. And the stupid, fashionable claim that there is no point in applying the laws against that sinister poison, cannabis, will be shown up for what it is – selfish, dangerous tripe. Where we can save people from destroying themselves, we must do so.'

He says 'We will not have such proof, since this is not prohibition, and is also following rather than leading public attitudes (quite apart from other confounding factors which mean this is nothing like a controlled experiment).'

**As I said before, I shan't argue definitions. It will certainly be called 'prohibition' by some people. It will involve the use of law strongly to discourage the possession consumption of the drug. And it will work.

As for 'following rather than leading public attitudes', I do not know how old Mr Wilkinson is, but my conscious life has more or less spanned the period in which cigarette smoking has moved from being normal and accepted to pariah status – and the period during which drunken driving was severely discouraged by moral pressure and law (law being far more effective).

In both cases, the authorities spent a great deal of time and money changing attitudes. Plenty of people refused to accept that it was wrong to drink and drive, for many years after it was obviously so. It was many years before Richard Doll's first report and a general acceptance in society that smoking was likely to lead to serious health dangers. In both cases the government had to 'lead' public opinion, not follow it. For many years otherwise intelligent people maintained that the correlation between tobacco smoking, lung cancer, emphysema and heart disease was just that, correlation without connection (where else have I heard that?) And in both cases it was the judicious and thoughtful application of the law which helped to drive these activities out of the mainstream.

I am not sure I seek a 'controlled experiment'. Mainly I want to scare irresponsible and easily led young people out of making a stupid mistake with their lives and possibly doing themselves horrible, irreversible physical damage. But it would be easy to compare a period during which cannabis possession was illegal in practice, with the period since 1972, when it has been illegal in theory but increasingly legal in practice.

More soon.

July 4, 2011

Think it possible that ye may be mistaken

The first slice of my response to Tim Wilkinson's challenge, on the subject of drugs and the law, on his blog 'Surely Some Mistake', follows. I have been grazing on the southern slopes of his enormous article, and do not claim to have dealt with it all yet.

I will be selecting several key passages (well, key passages in my view) from Mr Wilkinson's challenge, and will reply to them piece by piece. My replies are marked thus**.

I think this technique makes the argument easier to follow.

Mr Wilkinson opens: "My starting point is that we should presume that behaviours should be legal, and then ask - are there good reasons to make this behaviour a criminal offence? "

**Mine is slightly different. I don't think, as Mr Wilkinson implies, that we are naturally lawful creatures. I start from a willing acknowledgement that there will have to be laws.

I presume that any civilised society will require laws, because – while a society ruled entirely by conscience is a theoretical ideal – in practice we know that we cannot rely on conscience alone. On the contrary, by doing so we put the just and the conscientious at the mercy of the disobedient.

And in any case Utopia can only ever be approached (though never reached) across an ocean of blood. We should steer clear of attempts at perfection and accept that government is often a matter of choosing between one set of disadvantages and another.

Some consequences follow from this, consequences which are unappealing to many. There are those who wish to do what they want and think they should be the judges of whether it is right. In many cases these are people who believe that, because their freedom to take an action has done them no harm (or so they think), then it should be licensed for all. There are those who dislike inflicting any kind of hurt on others and abdicate responsibility for the penal enforcement of laws. Laws, to be laws at all, must apply to all, not just to some.

Laws must also ultimately be enforced with punishments for those who break them, punishments which by their nature cannot be pleasant.

And many actions which are or appear to be harmless for one individual, particularly a wealthy and strong one – are disastrous if adopted by the poor and weak. No-fault divorce is one example of this. I believe the taking of some drugs is another. I here make a point that will recur throughout this discussion. The response to each problem will be different. I would not, for instance, make divorce a criminal offence. But I would reinstate the pre-1972 criminal law for cannabis, which meant that its possession was treated as seriously as trafficking, and that a first-offender could (and sometimes did) go to prison.

Mr Wilkinson continues: 'My answer is no. Ordinary cannabis users derive great enjoyment and – yes – pleasure from their indulgence in the weed. Many report taking it in modest quantities and find that it aids relaxation, enhances their appreciation of food, music, art and sex, and even stimulates creativity.'

**And I reply 'So what?' I believe there are people who enjoy mistreating animals. For all I know they say it enhances their appreciation of art, food , music and sex, and stimulates creativity – though I haven't a clue how one would measure any of these things anyway. I couldn't care less. Their pleasure in this activity is of no interest or consequence in any discussion of what the law should say about cruelty to animals.

And no, I am not comparing cannabis smoking to cruelty to animals, merely demonstrating that the point is irrelevant.

Mr Wilkinson proceeds: 'To deny these benefits by more effective prohibition would involve far more oppressive measures,'

**I am a little lost here. Something seems to have gone missing. Far more oppressive than what? And in any case the purpose of strengthening and enforcing an (existing if weakened law) is not to deny anyone any pleasure. That is propaganda. Pleasure may be denied, but that is not the purpose of the law. As we shall see.

As for 'oppressive', I do not think this word can be used for a law which punishes the measurable possession of an illegal substance with stipulated penalties. If it is right for the substance to be illegal (the core of the argument) then it is right for the law to punish its possession. We are not talking about freedom of speech or thought here.

Mr Wilkinson continues: 'for the sake of preventing abusive overindulgence and the risk of cancer which accompanies smoking (though not as far as I know ingestion or inhalation of vapour). Those risks could be adequately mitigated, or in the case of the cancer risk, properly and – one might hope - honestly publicised, under legalisation and regulation.'

**I am not sure what is meant here by 'abusive overindulgence'. As for the risk of cancer, while it undoubtedly exists, it is not my principal concern.

Mr Wilkinson continues: 'Overblown claims about the dangers are rightly seen as ridiculous by those who know anything about it.'

**This is the most problematic statement in his argument so far.

It is perhaps the most important point on which both sides must work with the same material. I want to know precisely which claims he views as 'overblown', and whether he accepts that cannabis has – or might in future be found to have - any dangers for those who use it. And if so, what he believes those dangers are.

He continues: 'which makes officialdom look foolish and means that even accurate information is likely to be disregarded.'

**I'm all in favour of avoiding overblown claims. As he rightly says, they are likely to be laughed at. One recalls the 'Heroin Screws You Up' advertisement. He will not find me making claims about people dying from drug abuse (though some do) because I don't regard it as the main danger, and I too think it unwise to overstate my case with incredible claims.

And I do in any case have a parallel case against the legalisation of stupefying substances, which would stand if they were physically harmless.

Let me sum this up: First, morally – the pleasure and joy and exaltation provided artificially by drugs, and naturally by the human body are rewards for effort and courage. You may believe this is a created fact or the consequence of evolutionary biology, but the arrangement is beneficial to humankind because it limits this reward to those who have earned it. If you haven't delivered the Gettysburg address, or won the Second World War, or designed St Paul's Cathedral, or written Beethoven's Violin Concerto, you shouldn't be able to feel as if you had. If you can, then people will stop doing these things. I might add Allan Bloom's point in 'The Closing of the American Mind', to some extent backed up by Tim Lott in 'The Scent of Dried Roses', that those who have achieved exaltation through drugs in early life are left afterwards with an emptiness, a flatness, an absence of the superlative, which stays with them all their lives. I have a strong suspicion that the human body has only a limited capacity to deliver the sensation of joy, and that the use of drugs eventually exhausts it, with sad consequences for the individual.

Obviously the religious person would see something straightforwardly wrong in messing around with the gifts of God in this way. But the Atheist (I'll have an interesting example of this later) also might consider that there are good rational and material justifications for restraining unwise and impulsive young people from consuming chemicals which might - unexpectedly and irreversibly - drain all the colour out of their later lives.

Next there is the argument from human liberty and responsibility. Aldous Huxley's imaginary drug Soma was a key part of the soft but devastating repressive apparatus of his Brave New World. In one scene a riot is actually put down by police spraying Soma on an angry crowd of Deltas. I think there is a powerful point in this. Rulers may well be glad to have a population which is numbed by artificial pleasure, and can take a holiday from reality( and responsibility, and legitimate discontent) by ingesting a happiness drug. Creating contentment where there should be discontent, dulling eyes that should be clear, closing ears that ought to be hearing the sound of dissent , drowning protests in giggles and manufacturing chemical happiness where there ought to be criticism and reform are all – surely - things which those honestly interested in freedom should dislike.

Mr Wilkinson goes on: 'Legal regulated cannabis would be of known strength and free from such very harmful adulterants as wax, petrol, even plastic, which can be found in poor-quality illegal hashish.'

**The same can be said of tobacco, alcohol and motor cars, three legal scourges which we already have among us. If the substance, or the commodity is fundamentally damaging anyway, listing its contents on the packet, surrounding it with safety regulations or keeping it free from impurities will not get rid of the fundamental damage it does. It will only make it more 'acceptable' while allowing the wrong to continue. Indeed, the campaign to make motor cars safer has indeed made them safer for those inside them, but it has done little or nothing for the safety of pedestrians and cyclists, and road casualties have fallen mainly because so many children no longer dare bicycle to school (or their parents daren't let them) and because of a rigid apartheid which keeps pedestrians from getting in the way of cars, shoving them into tunnels or forcing them to wait long minutes while humorously-entitled 'pedestrian-controlled traffic lights' wait to change in their favour.

So no, 'regulation' of something fundamentally bad doesn't get rid of its fundamental badness. Sometimes we may have to accept it as a compromise while we try to remove a poison from our culture, or at least greatly restrict it. But that is a defeat, and there is no need to acknowledge defeat with cannabis. It is nothing like so deep in our culture as cars, alcohol or tobacco. Not yet, anyway. 'Regulation' would help to make it so.

Mr Wilkinson says: 'The current system already exposes users to criminal sanctions and means they must become involved at the margins of the criminal world to get hold of it, with the concomitant aversion to police and contempt for the law."

**This is not really true. There are no serious criminal sanctions for possession of cannabis, and most 'dealers' are not Colombian gangsters or Sam Giancana-lookalikes in fedoras, but a mate at school or in the pub.

Also what is this word 'must'?

They don't have to get hold of it. They want to. They know it is illegal. But alas, they also know the law isn't enforced. That is the reason for their contempt for the law, that it is contemptible. It pretends to exist, but doesn't. As for 'aversion to the police', hard to feel much aversion for people you never see.

July 3, 2011

Just text 'Claim' ... then give these vultures both barrels!

This is Peter's Mail on Sunday column

Parliament does plenty of stupid things without meaning to. Mainly this is because MPs are too ill-informed or lazy, or too dogmatic, or too much under the thumb of Downing Street, to see the damage they are doing. The voices of warning are dismissed as 'extremists' or told abruptly 'This is the 21st Century, you know', as if that made any difference.

That's why a rich, peaceful, beautiful country is fast turning into an unstable, disorderly, impoverished slum. But there's one case where nobody can pretend they didn't know what was coming.

This is the deliberate creation of a whole new caste of greedy, cynical ambulance-chasing lawyers. Whenever you hear of a stupid case of 'Health and Safety' dictatorship, it's these people, not 'Human Rights' or Political Correctness, who are to blame. That's why councils ban cheese-rolling festivals and veterans' parades. That's why it says 'Contents may be hot' on the lids of coffee cups, why there are notices next to rivers saying 'Danger, deep water'.

For once, you cannot even pin the responsibility on the ghastly Blair creature or his accomplice, Gordon Brown. In fact, Labour's Jack Straw has earned himself some credit for exposing some of the seamier aspects of this already seamy apology for an industry.

The culprits were the last Tory Government, which in 1990 passed Section 58 of the Courts And Legal Services Act and then went on to push through the Conditional Fee Agreements Regulations, approved as a Statutory Instrument in 1995.

Until then, no-win, no-fee cases were not allowed here. And anyone who wondered why not needed only to go to the USA and look. I remember laughing about TV commercials for injury lawyers when I first went there in 1977. Mad, risk-free lawsuits led to madder awards, and to ridiculously expensive insurance premiums.

I don't in any way condone or excuse this, but it is the case in Britain now that young men find it incredibly hard to get affordable car insurance, and many drive uninsured.

There's also the distasteful business of the lawyers themselves, circling high above the misfortunes of others, then descending to pick at the remains like carrion crows. Some of you may remember Paul Newman playing such a lawyer in the 1982 film The Verdict – a miserable deadbeat hanging round undertakers' chapels handing out his card to the bereaved.

There's not much difference between that pathetic figure and the very unpleasant and thuggish-sounding individuals who have for weeks been pestering me with text messages on my mobile phone, about a non-existent accident.

They wouldn't stop when asked but when I finally lost patience and texted 'Claim' to them, they came rushing like sharks to blood in the water. I recommend this course to anyone. It wastes their time and money, and gives you a chance to tell them what you think of them.

The huge British Embassy in Washington DC, if asked, could easily have sent back a report to the British Government, warning of all the nasty consequences of this change. That's assuming they didn't already know. But because they wanted to cut the Legal Aid budget at all costs, they went ahead.

I would guess that the cost to the British people of this irresponsible measure is thousands of times greater than the bill for Legal Aid ever was or could be. But it doesn't appear on the Government accounts, so they can pretend it is a saving.

It has gone on long enough. A single, simple Act of Parliament could be passed in a few weeks to put it right. It should happen soon.

Mr Speaker, the essential voice of British cussedness

It's time to stand up for Speaker Bercow, all the more because I don't like his politics or the fact that he has been gratuitously and ignorantly rude about our sister newspaper the Daily Mail.

Mr Bercow is the best Speaker for years. He keeps business moving fast. He drags Ministers from their desks to answer urgent questions, as he should. And, in a Parliament where there is no Opposition worthy of the name, and where the media have become fawning pets of the Prime Minister, he is the authentic voice of good old British cussedness.

You'd think, from the shocked way in which these incidents are reported, that there was something wrong with the Speaker telling the Prime Minister to stick to the rules, and inflicting a bit of sarcasm on this slippery, merciless bully.

You'd think that the Government was supposed to have the Speaker in its pocket, and that it was good for our constitution for this to be so. Well, the dwindling numbers of us who know the history of our nation and its people understand that when there's a battle between the Speaker and the State, the Speaker is the one to back. Don't let them scare you, Mr Bercow.

Bound for Gaza with a cargo of propaganda

We must all get ready for another season of ignorant attacks on Israel as a new fleet of alleged relief ships heads for Gaza. It is not relief. It is propaganda. How do I know? Last September I visited Gaza, with some trepidation.

I found plenty of misery there, though it is clear that much of this is maintained for propaganda reasons and could easily be put right by the rich Arab world if it wanted to. But I also found many things that the propaganda reports do not mention – including a shopping mall, beach parties and luxury restaurants.

I inspected the enormous tunnels through which large quantities of goods, including cattle and building materials, are smuggled from Egypt. There is also, in this so-called prison camp, quite a lot of open space, much of which I am glad to say is now being used for the cultivation of food.

Those who doubt my word are urged to read a series of reports in the Left-wing New York Times, which last week reported the opening in Gaza City of a second shopping mall and two luxury hotels.

We should ALL object to this airport humiliation

The demeaning, illogical humiliation of air passengers is quite bad enough as it is. Eye surgeon Antonio Aguirre was right to object to being forced to undergo an X-ray body scan. When he declined, fearing for his health, he was forbidden to fly at all. This is a severe punishment imposed without any proper legal process, quite wrong in a free country.

Not only does this, in effect, mean that staff can force us to show them our naked bodies. It is by no means clear that the radiation levels are as safe as the authorities claim. Even in the USA, where air security is two degrees above hysterical, passengers are offered a choice between scanners and a search.

The treatment of air passengers as powerless serfs, not even allowed to joke about their ridiculous treatment, shows us how our rulers would like to behave all the time if only they could, and what they really think of us.

The pretext of 'security' is not good enough and should be questioned every time it is advanced.

Who sneers at Oxbridge? Er, the BBC, Mr Paxman

Only those who have lived in communist states ever understand me when I say that this country is turning into a People's Republic in all but name. But maybe this will alert the complacent. The BBC presenter Jeremy Paxman amazingly urges the holders of Oxbridge degrees not to be ashamed of them. He says: 'Why there should be any shame attached to them I simply do not know.'

I do. I can think of no other country in the world where attendance at its finest universities should be seen as shameful. But then no other country has the BBC, where the gilded beneficiaries of British liberty work day and night to denigrate the country that gave them all they have, its institutions, its laws, its faith and its traditions.

*****************

The silly strikers need David Cameron, and David Cameron needs the silly strikers. They can pretend that he is a ruthless cutter of public spending (which he will enjoy, because he isn't but would like his supporters to think he is). He can pretend that they are a powerful and dangerous force in society (which the unions will like because they aren't, but would like their supporters to think they are).

June 30, 2011

A New Challenge on Drugs

I just want to give notice here that I shall shortly (early next week, I hope) be responding to a challenge from Tim Wilkinson who, on his blog 'Surely Some Mistake' has set out his reasons for opposing my call for the proper enforcement of penal laws against the possession of drugs, notably cannabis. I think anyone with a search engine can find their way there, and it would be useful if readers here were familiar with the arguments which Mr Wilkinson has put, before I get started.

This debate, by the way, is by arrangement. We have a friend in common who suggested that we should discuss this matter. Mr Wilkinson is of course welcome to post replies here as well as on his own site. I shall post my arguments here, and nowhere else.

I am now in the early stages of wring my planned next book 'The War We Never Fought', which examines the secret surrender of the British establishment to the cannabis lobby in the late 1960s, and the results of this surrender. So I am particularly looking forward to this exchange.

Let us see if we can keep the Atheist Bores from turning it into a linguistic battle over the difference between 'not believing in God' and 'believing there is no God'. I am pleased to see that so far they haven't hijacked the discussion on World War two, but I'm not sure this can last much longer.

June 27, 2011

Summer Reading

During some recent long train and plane journeys I've read three powerful works of modern history. The first is Michael Burleigh's 'Moral Combat', often advanced as an answer to the doubts of people like me about the moral purity of World War Two.

Then I turned to 'The Third Reich in Power' by Richard Evans, the second volume of his trilogy which examines the Hitler period. This is particularly interesting because most general books on the subject concentrate on Hitler's coming to power and on the war. This one goes into rather more detail about how National Socialism operated and achieved its ends.

Finally, I read 'To End All Wars' by Adam Hochschild, a revelatory and almost wholly fresh study of opposition( such as it was) to the First World War.

The first thing I'd like to say is that Hochschild actually made me change my mind. I have for many years crabbily resisted attempts to rehabilitate the soldiers shot for desertion during the 1914-18 war. I took the view that the great majority did what they believed to be their duty, and that those who didn't couldn't and shouldn't be accorded the same status.

But his account of the treatment of several of these cases completely overturned my view. I now feel that I was quite wrong, and withdraw what I have said in the past. These men most certainly deserve to be honoured. The truth is that I have suspected this for years, and should have shifted long ago, but it took the incidents in this book to push me over the hump.

I would also say that Hochschild more or less demolishes any remaining justification for fighting this war at all. My only disappointment is that he gives far less space than he ought to Viscount Lansdowne's attempt to call for a negotiated peace, which if heeded might have saved the world from much (there is a moment in Huxley's 'Brave New World' where Lansdowne's failure is noted as a turning point of modern history, a vast conservative failure and one of the reasons for the Fordist revolution which wiped out history, privacy, the family and religion).

I realised as a small boy in late 1950s Britain that the First World War had destroyed an order that was in many ways admirable. It was obvious, from studying the ancient pre-1914 volumes of 'Punch' in my prep school library, that the world before the battle of Mons was calmer, sweeter, more settled and in many important ways happier than what followed. These books were not trying to give this impression. Like old advertisements and guide books, they gave a disarmingly frank impression of how people actually felt and lived at the time. People will tell me about slums, the crudities of empire, malnutrition and so forth, and they will be right. But isn't it false to imagine that the world would have remained exactly the same in all ways.

Without the war, we could have made plenty of social progress, perhaps more. Above all, we would not have lost all those men, the flower of their generation, who volunteered for what they thought was a noble cause. Not to mention avoiding the Russian coup de'etat - and Hitler, Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin and Mussolini remaining obscure and unknown failures till their lives' ends.

Here I'll turn briefly to 'The Third Reich in Power', which seemed to me to show that the National Socialist regime was far more socially radical than its present-day critics like to acknowledge. Its cult of youth was a particular menace to proper education, as it stripped power from teachers – and parents - and gave it to aggressive Hitler Youths. I still feel the lack of a really thorough look at this movement in English (if anyone knows of one, I'd be grateful) as it played a huge part in undermining religion and destroying parental influence, and was also pretty relaxed (as were most of the Nazi hierarchy) about premarital and extramarital sex. Though it is from Michael Burleigh's book that I learned that Nazi Germany's 1936 divorce laws accepted 'irretrievable breakdown' as a ground for divorce, 33 years 'ahead' of Britain's decision to do the same. The idea that National Socialism was a form of conservatism, or allied to it, really does not stand up to much examination.

It had, in these areas, plenty in common with the Communist regime in Stalin's USSR.

And it could not progress without coming into severe conflict with the churches, a conflict which would have been far more virulent had Hitler and his government survived longer than the 12 years they actually had.

It was also deeply hostile to the rule of law, and to the independence of the courts. Likewise the universities, the professions, the newspapers, were all ingested in much the same way that a left-wing totalitarian regime would have used. The mass robbery of the Jews was, as in all revolutionary expropriation, a convenient way of rewarding the revolutionary party's supporters, with money and jobs.

The conduct of political conservatives was often shameful and generally mistaken, though they could not know the horrible future. Many of the clergy were too narrowly concerned with their own interests and never widened their attacks to encompass the regime as a whole. Mind you, nor did anybody else.

But Franz von Papen's Marburg speech, and the Vatican's secret distribution of its 'Mit Brennende Sorge' document, were both startlingly bold challenges to the National Socialists, which infuriated Hitler and provoked severe reprisals. The left were also often courageous (I have mentioned here the extraordinary courage of the Social Democrat Otto Wels in the final hours of a free Reichstag) , but the Communists in particular behaved as stupidly ( if not more so) than the German conservatives. I think it important to note that conservatives and Christians resisted, and were attacked for their resistance. I still gasp with sheer astonishment at the aristocratic scorn for the Gestapo repeatedly shown by Cardinal Archbishop Graf von Galen, whose story should be better known. He defied Hitler over many subjects, in public, but I would like to note here that one of his fiercest battles was against the National Socialist euthanasia programme.

This brings me to Michael Burleigh's disappointing book. Far from being a thorough retort to ( say ) A.C.Grayling's 'Among the Dead Cities', which I discussed here last year, it seems to me to miss the point made by most of those who condemn the bombing of German civilians.

What we are *not* saying is that this bombing was the moral equivalent of the massacre of the Jews. It was not, and those in Germany or elsewhere who have attempted to suggest any such thing are not my allies.

What we are saying is that war fought in this way, and in alliance with the wholly immoral USSR, cannot continue to be exalted as some sort of holy conflict.

This alleged holiness obscures an honest assessment of its rights and wrongs, leads to an emotional rather than a rational analysis of Britain's part in it, and leads to silly evasion of responsibility for actions which ought never to have been taken. It also leads to the perpetual misuse of the 1939-45 war as the model for modern interventionist diplomacy – a model based on a wholly wrong understanding of why and how we fought the 1939-45 war.

In my attempt (last year) to discuss the timing and purpose of Britain's entry into the war, so mistimed that it nearly got us subjugated, I ran into an emotional blockage from many readers who simply could not get past the frayed and increasingly insupportable myth of the 'Finest Hour'. This is always coupled with a standard set of beliefs about the occupation of the Rhineland and the later Munich crisis, in which it is assumed that a serious alternative policy was a) available at the time and b) practicable at the time and c) would have led to a better outcome.

Thus they could not properly examine the incompetence of British diplomacy in the late 1930s, and its absolute nadir, the ludicrous and dishonest guarantee to Poland, which allowed Colonel Beck, at his desk in Warsaw, to decide when or if we went to war with Germany ( and why).

One of my critics was reduced to inventing non-existent declarations by Hitler and non-existent intelligence documents, in trying to show that Hitler would have attacked Britain in 1940 whatever we had done. Unflattering as it is for our national ego, I don't think he cared enough.

Until we can start looking at 1939 with the dispassionate coolness rightly used to examine the 1914-18 war, we won't be able to make sense of it and (in my opinion) we will not cure ourselves of the urge to go out and bomb countries such as Libya for their own good.

A few thoughts about the Burleigh book. First some quibbles. He says (on page 489) that German bombers 'achieved a firestorm' in Coventry on 14-15 November 1940. I had never heard this before and do not think it true. Coventry was a filthy massacre, but not a firestorm. He also (I am genuinely baffled by this in someone who spends so much time researching German history) states (on page 550) that 'FDR' stands for the Federal Republic of Germany. It doesn't, in English or German. The error is repeated in the paperback.

These are minor niggles, but they made me uncomfortable. It is more important when he uses words as he does about those who disagree with him, for example (p.487) 'Sir Arthur Harris, bête noire of the moral-equivalence claque'.

Well, if there is such a claque, Sir Arthur may well be its bete noire. But he is also the bête noire of people who compare the casualty rate among his airmen to that at the Somme in 1916, and to those who, having no belief in moral equivalence, and are not a 'claque', even so think that the deliberate bombing of German civilians in their homes was wrong in itself (and also that it was ineffectual, though it would have been wrong even if it hadn't been).

The same rather blustering tone is to be found when he (on page 501) attacks 'Moralistic arguments that selected some but not all aspects of war fighting'.

In a book entitled 'Moral Combat', it seems a bit odd to be so dismissive. Aren't such arguments simply 'moral' rather than moralistic? Isn't that how they are conducted? Isn't the existence of a moral rule about just war the whole reason for his book?

In another baffling passage he praises Archbishop Cosmo Lang on the grounds that he 'had the good sense to know that clerics had no special competence to comment in these issues' (area bombing).He says this was: 'a humility lost on some of his contemporaries and successors'.(502-3).