Sandra Gulland's Blog, page 15

September 29, 2014

A writer’s routine: how to be productive

A friend asks:

When you first started your career as a writer, was there something you were doing each day, which you now know to be unproductive?

When I look back on my early days, in fact, I’m amazed that I accomplished as much as I did. My husband was often away, and I had two children, a dog, horses, a garden and chickens to look after. Plus, I was still editing free-lance and active in my community: co-editor of a newsletter and volunteer principal of an alternative school.

How did I do it?

The magic word: no

The answer, in part, is that I was young, but mainly I learned to start saying NO—perhaps the most important word in a writer’s vocabulary.

When I got the contract to write the Trilogy the first thing I realized is that I would have to give up my community volunteer work.

I didn’t want to, but there is a limit to how much one can do. I couldn’t fool myself into thinking that my life would carry on a usual and that somehow these novels would magically get written. Something had to give.

I also put my paid editorial work on the back burner: I gave my best hours—my morning hours—to writing.

A novel needs room to grow. Ask yourself: What can I give up? How can I make more time in my day?

Make writing the priority. Put it at the top of your To Do List.

Write Time: Guide to the Creative Process, from Vision through Revision-and Beyond (formerly titled A Writer’s Time) by Kenneth Atchity is a good book on how to get a book written and—most importantly—revised. Unlike a lot of books on writing, his is practical, the nuts ‘n bolts of tackling a big job.

One of Atchity’s suggestions that I have found useful all these many years is to include holidays in the writing process: by finishing drafts before a holiday, you give it time to “age,” and return to it with a fresh perspective.

Also in the making-breaks-work-for-you vein (a blog post): The New Habit Challenge.

Other posts in this series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative head space

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

A writer’s routine: where to write

A writer’s routine: on resisting an outline

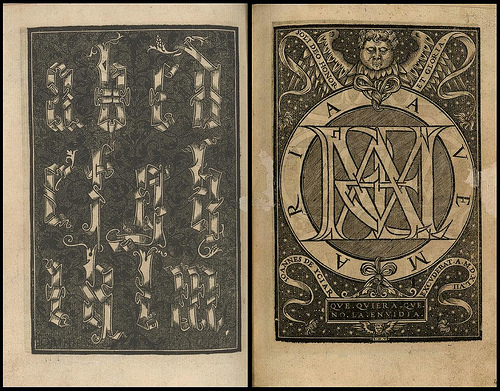

{Illustration at top is from “A Most Delicate Art” at BibliOdyssey.}

September 27, 2014

A writer’s routine: on resisting an outline

A friend asks:

What have you learned over the course of your career that you wish you knew at the beginning, in terms of your writing routine/productivity?

I wish I had known how important it was to outline before beginning to write. I might have saved myself years of fruitless effort.

Resisting outlining

Like all novice writers, and many very experienced writers as well, I detested the thought of outlining in large part because I didn’t understand that an outline is an early draft (a conceptual draft) of the story, but also because I associated outlining with the dreaded word plot.

One reason I initially leaned toward writing historical fiction was that I mistakenly thought that the plot was already there, laid out before me in the historical record.

Wrong, wrong, wrong!

I also felt that since I was “no good” at creating a plot, I would be sidestepping this weakness by writing biographical historical fiction.

Wrong again.

What I’ve learned over all these many years is that:

1) history is merely the stuff from which a plot must be created;

2) a writer can — and must — learn about plotting.

What’s wrong with being a Pantster?

Some writers—often the “pantsters,” those who proclaim against outline—have an intuitive feel for story, gleaned from decades of reading and revising. They also usually take years longer to find their story arc.

A novel will take years to write one way or another, but without a plot outline, it will take—I venture to guess—twice as long.

So you decide:

a pantster novel: 8 years

a plotter novel: 4 years

But aren’t plotter novels “commercial,” and pantster novels “literary”?

Wrong again. There are both plotter and pantster novelists in every genre.

Why writers resist writing an outline …

1) It’s hard.

2) It’s abstract, conceptual.

3) (For some) One needs to—or should—first study the mechanics of plot.

Imagine that you are going to build a house. It’s kind of fun to think of ordering in piles of lumber and just begin sawing and hammering away.

You can see where this is leading.

Instead, of course, a builder begins with a plan, a plan that will go through many, many drafts. Once the plan is fully refined, the building begins. But even then, changes will be made and it’s “back to the drawing table,” as they say.

In the case of a novel, rather large changes will often be made, and then, too, it’s “back to the drawing table”—that is, back to the outline.

The many shapes and sizes of an outline

There is a mistaken idea that an outline puts a writer in a straightjacket and that the actual writing then becomes formulaic, mechanical and … Well, one often sees the word boring used.

This is not how it works.

A novel is conceived in imagination. And then notes. And then more notes: voices, scenes, snippets of dialogue. These begin to congeal, cluster, take form. At some “quickening” point, these notes can be laid out (or, if on computer, shifted around) to form a story arc.

And there you have it: an outline. It may be a one-page sketch, a stack of index cards, or a 40-page document. (My preference at this time is to create a scene-by-scene outline.) There will be gaps, places you know something has to happen, but you don’t yet know what it is or how it’s going to come about. What you do have is a shape: a beginning, a middle and an end.

For the next draft, the first in fully written form, and for all the many drafts that will come after, many things will change. But without an initial “conceptual” draft, you will be looking for the story instead of fulfilling the story: and that’s the difference.

Required reading! From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction, by Robert Olen Butler—specifically Chapter Five, “A Writer Prepares.”

When it comes to plot, I’m a big fan of books by screenwriters, the plot-masters. Here are my favourites:

Save the Cat, by Blake Snyder. I especially recommend this book because it is short, amusing, and to the point.

Story, by Robert McKee.

The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers, by Christopher Vogler. I love this book. It’s especially relevant with respect to character, and the role of different characters in a story.

Other posts in this series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative head space

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

September 18, 2014

A writer’s routine: where to write

My friend asks:

Where do you write?

If in multiple spots, do you find any difference in your quality of work?

Have you tried writing in places that just don’t work? (I.e. couch, bed, yard, park, coffee shop, etc?)

Do you like having windows to look out? Or, shut the blinds?

Do you need silence or listen to music?

Are you okay writing with other people or pets in the house, or do you need quiet?

Do you have a special chair? Writing hat or outfit?

I love having my own office space, and I think I would have a hard time writing without one. That said, the important thing is to feel detached from the world so that I can immerse myself on the page, and this can be achieved in a number of ways. When I’m travelling, for example, sharing a room, or in a busy space, I wear ear plugs and headphones.

I write on a laptop—my beloved MacBook—and usually sit on a couch with the mouse on a thick book beside me. I find that more comfortable ergonomically than sitting at a desk.

If you work at a desk, and even if not, it is important to move, stand, walk, swing your arms—do something—every hour, if not more often. I found this out the hard way. At one point my right hand was in such pain I thought I would have to give up writing. Now I set a timer. It’s shocking how quickly an hour goes by … and also shocking how serious the effects of concentrated time at a computer can be. Move. Change position. Exercise.

Some writers thrive writing in a public space—a coffee shop or library—but I think I would be distracted. I like having windows—light!—and I prefer being able to come and go without being interrupted. I’m not at the computer then, but I’m thinking. Dreaming is a writer’s work. We mutter and pace. Dickens would have lively dialogues looking into a mirror. I think you have to have enough privacy so that you can mutter and gestulate without embarrassment, which could be a problem in a public place.

I need to feel safe from interruption at certain stages of the writing process. In my early years of writing, I would only schedule home repairmen etc. for Mondays or Fridays, so that I had a run of house-empty days in the middle of the week. I’m fairly strict about protecting my morning hours. It’s important to let your family know when you need solitude.

With time, one learns to immerse more easily, and distractions become more manageable. Professional writers, especially those who are often on tour, learn to write all the time under any circumstance.

A relevant book: The Writer’s Desk, by Jill Krementz:

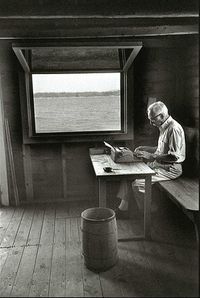

This from a Paris Review interview of the historian David McCullough, “The Art of Biography, pt. 2“:

“Nothing good was ever written in a large room,” David McCullough says, and so his own office has been reduced to a windowed shed in the backyard of his Martha’s Vineyard home. Known as “the bookshop,” the shed does not have a telephone or running water. Its primary contents are a Royal typewriter, a green banker’s lamp, and a desk, which McCullough keeps control over by “flushing out” the loose papers after each chapter is finished. The view from inside the bookshop is of a sagging barn surrounded by pasture. To keep from being startled, McCullough asks his family members to whistle as they approach the shed where he is writing.”

I was charmed to learn that McCullough doesn’t allow any visitors, with the exception of grandchildren, “the younger the better.”

The ergonomics of writing often dictate where and how one writes. A number of authors—most famously Hemingway—use stand-up desks (some even like treadmill-desks). Lin Enger, author of The High Divide, had this to say on the blog The Quivering Pen:

I wrote most of this novel in a four-by-five closet, standing up. Sitting for any length of time wrecks my lower back, and so I resorted to using for my desk the top of a four-drawer file cabinet I kept in the closet of my study. Why didn’t I move the cabinet into the study itself? Because the isolation of standing in a small, windowless room helped me disappear into the northern plains of 1886.

And, perfect reading for this subject, a book that influenced me decades ago:

A Room of One’s Own, by Virginia Woolf.

I’ve long loved this image —

Other posts in this series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative headspace

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

{Illustration at top is from “A Most Delicate Art” at BibliOdyssey.}

September 15, 2014

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

My friend asks:

How many words do you write a day? For how long do you write? How many days a week?

In other words, what’s the production schedule?

This may strike some as a mechanical approach to a somewhat mystical process, but for me and many other writers, it’s key.

Daily goals

The more you write, the better you get. It’s that simple.

The aim of the first draft is to get from the beginning to the end.

Keep in mind Anne Lamott‘s mantra: “I am responsible for quantity. God is responsible for quality.”

Many writers set daily goals. Mine are usually 1000 to 1500 words on work days, 100 words on “off” days (sick days, travel, family, and commotion days).

At the challenging beginning of a project, or after a time away, I will start with modest goals: 100, 200, 300 words a day, building up to 1000 or 1500. Be gentle with yourself, but persevering.

I clock in first thing, using “word count” to record the number of words in the manuscript file. I write this number on a calendar (a small Levenger notebook I buy for this purpose), write down my assigned allotment for the day and record the sum. Circle it. That’s the word count I must meet.

When I’ve met or exceeded that word count, I calculate how many words I’ve added to the manuscript. Write that down. Put an exclamation mark or smiley face beside it if I’ve done well. All those grade-school things.

This method encourages me to write new material every day, move the manuscript forward. Once my daily goal is met, I may go back and edit, fuss, cut, rewrite to my heart’s content.

Some days I’m like a tired factory worker and stop the instant I hit my goal. On other days I will write hundreds of words more without even noticing.

What about burn-out?

My friends also asks:

Are there times when you have burnt out on writing? If so, how hard were you pushing and what did you learn from that experience?

Getting to the end of a draft, getting a novel ready to send out, is completely exhausting. Crossing that finish line! (Some have asked, “How do you know when you are finished?” Exhaustion is the clue.)

It’s okay to exhaust yourself at the end—but it can derail you in earlier stages. Pacing is important. You are an athlete.

In setting your daily writing goals, it’s important to under-estimate what you can do in a day. It has to be achievable.

And, as I will say over and over: writing daily is key.

Not all stages of writing can be measured by word count. Working on a plot counts as “writing”; so does dreaming scenes, research and revision.

I like to keep the pressure on (I am my own task-master), so I will devise some appropriate daily goal or deadline—i.e., so many pages revised a day, an outline of two chapters, one character sketch—in order to keep moving forward.

Pushing through resistance

It’s important to realize that the first stage of writing is resistance to writing. Stage two is finding a way to push through that resistance.

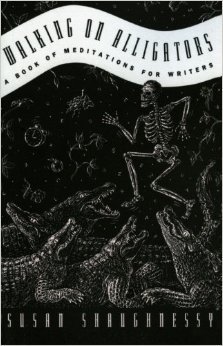

For overcoming resistance, I recommend Walking on Alligators, a book of meditations for writers, by Susan Shaughnessy.

Still having trouble? I’ve become a fan of Jerry Seinfeld‘s “Don’t break the chain” method for motivating myself to do something daily. (It has succeeded in getting me to exercise daily, a small miracle.) For a year-at-a-glance continuous calendar, click here, or click here to download my own.

Websites on this very effective system:

Jerry Seinfeld’s Productivity Secret

Other posts in the “writer’s routine” series so far:

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative headspace

September 13, 2014

A writer’s routine: pantster or plotter?

Pantster or Plotter?

Writers often talk about whether it is better to be a “pantster” or a “plotter.” (Google “pantster or plotter” and you will get some idea.) A pantster is someone who writes “by the seat of their pants”—that is, without an outline. A plotter, of course, is someone who begins with a plan.

I myself am a firm believer in having some kind of plan. The late great Alistair MacLeod used the analogy of a carpenter, who does not just take a bunch of random nails and two-by-fours and start banging. She knows, first, what she is trying to build. …

Virtually everyone detests making a plan—which might be a fifty-page detailed outline, a one-page summary of plot-points or a loose pile of index cards. Most beginning writers resist making a plan, citing the many fine writers who work without one. These writers are also experienced and take a very, very long time to complete a project.

Robert Olen Butler‘s book From Where you Dream is excellent on the pros and cons of working with or without a plan. See Chapter Five: “A Writer Prepares.” His conclusion is that working with a plan helps get a book written faster.

A plan helps getting that first draft on paper. When I was first starting out, I assembled clumps of index cards for each scene: character notes, details, plot points. Now I spend months evolving a scene-by-scene plot before I begin a first draft. Either way, I basically know where I’m headed each day.

Alison Pick: Writing Tips:

Having a plan doesn’t mean the plan isn’t flexible. It will change—dramaticaly—by the time it is transformed into an actual book. But a plan gives me confidence. It steers me in the right direction. Knowing loosely what has to happen in each chapter divides the process into baby steps. I can think of the book as a series of small tasks rather than one enormous one.

Books on plot

On plot, I highly recommend books for scriptwriters.

Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder is short, amusing and to-the-point.

Another great book is The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers by Christopher Vogler.

Vogler’s story structure is similar to that outlined by Blake Snyder simply because we are hard-wired for story (as originally explored by Joseph Cambell in Hero with a Thousand Faces).

Vogler describes character archetypes—the mentor, the trickster, the shadow, etc.—defining the roles of the various characters in a story.

Examining your story in terms of the classic story cycle and identifying the archetypes your various characters play will help you to refine it, make it stronger … and get it written faster.

Other posts in “A writer’s routine” series:

A writer’s routine: how many … hours, days, words?

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative headspace

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

{Illustration at the top is from BibliOdyessy.}

September 11, 2014

A writer’s routine: how to get into a creative headspace

My friend asks:

“Does it take you some time each day to immerse yourself in your writing? If so, any tricks to ease into the creative headspace?“

Writing has stages: a first draft is dream-like, immersive, while subsequent drafts are part cerebral/part immersive and often involve gnashing teeth, pulling hair, and moments of despair interspersed with joy.

Whatever the stage, you need to show up—daily.

For the early, intense and immersive writing stage, some recommend not speaking, talking or reading anything on waking, and to begin writing while still half-asleep. Others use a meditation practice to reach that imaginative space. Some write to specific music or look at an image chosen for a project. Many (Jane Smiley, for one) swear by a hot shower, or long walks. If there are distractions, I will use ear plugs as well as headphones.

Because the imaginative space can be so illusive, writers often try out different techniques. It’s hardest when you are new to writing, but it can be hard even for experienced writers, especially at the beginning of a new project. Over time, it gets easier to shut the world out, to concentrate, to lose yourself in a fictional world.

A writer needs to occupy an imaginative space for many months, perhaps even years. Touching base with it daily, even if only for a half-hour, is key. In my experience, one day away equals at least two days lost in trying to get back into that fictional world.

Some writers are night-time writers but most work in the early hours. If you begin first thing in the morning, you will be unconsciously thinking of your story all day.

The more you give yourself to your work, the more immersed you will become, and ideas will come to you in dreams or at unexpected moments. Many a writer has holed up in a bathroom at a party to note down thoughts.

Always have a notepad with you as well as one by your bed, so that you can write down the ideas that come to you on the fly. (A friend’s daughter calls these fly-by ideas “art attacks,” and dives for the closest paper and pencil.) Some writers use a dictation device that is always with them.

The important thing is to respect these thoughts. Don’t make the mistake of assuming you will remember them.

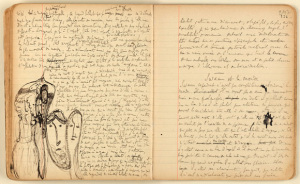

Proust‘s notebook:

At a critical point in the writing process—often nearing completion—a writer will seek some form of retreat, move into an isolated space in order to be able to concentrate fully. Over the years, I’ve checked into motels, B&Bs, silent monasteries, a snowed-in cabin.

The next question in “A writer’s routine” series: How do you conquer writer’s block? What do you do when you are looking for inspiration for your work?

Essential reading: Chapter 5, “Harnessing the Unconscious,” in Dorothea Brand‘s wonderful book Becoming a Writer.

These two books demonstrate how individual the writing process can be:

How I Write: the Secret Lives of Authors, edited by Dan Crowe: so that you re

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey.

Another post in the “A writer’s routine” series: Evolving what works.

{The opening image is from “A most delicate art” on BibliOdyessy.}

September 9, 2014

A writer’s routine: evolving what works

A friend has just quit his day job in order to devote full attention to writing. He has a number of interesting questions about writing, and especially about writing routines. Coincidentally, I’ve been reading Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey, so this is a subject very much on my mind.

Here is his first question:

What does your typical writing day look like broken down? I know you mentioned you write first thing in the morning. Do you wake up and start writing immediately (open eyes at 6:00 am and writing by 6:05 am), or do you take time to have breakfast and shower first?

Do you write 2 hours, then have breakfast? Go for a walk halfway through day, etc.

Every creative (writer, artist, composer) finds, by trial and error, a routine that works best, but here is mine:

I wake, usually around 6:00 am, make myself a mug of coffee and go directly to my computer. I glance at email (I can’t help it), and then begin the writing of the day. I call this my “Cup of Work,” and I hold to it daily, even while travelling.

It’s important for me to be in a private space, but if that’s not possible I wear ear plugs and headphones so as not to be distracted.

At around 8:00 I break to eat, dress, chat with my husband and plan the day. At 9:00, I go back to work, usually until 11:00, when I break to exercise, lunch, read, and attend to the chores of life, including the many non-writing tasks that are a necessary part of a writer’s life (correspondence, research and social media, for example).

I retire early, often around 9:30, and read for pleasure.

And that’s my day: it amounts to about four hours a day devoted to writing. On non-work days, I will at least have my Cup of Work first thing, although it might only be for a half-hour.

As a beginning writer, I used some tricks that might be of help. The day before, I would put notes by my computer, indicating the scene I was heading into. Because I was a mother of two youngsters, I had to rise before they did in order to get a jump on the day. I programmed the coffee pot to start perking so that when my alarm went off, the smell of the coffee lured me out of bed.

“There is no single way to be a writer. The most important thing to do is figure out what works for you.” — Alison Pick, Writing Tips

Next up, the question: “Does it take you some time each day to immerse yourself in your writing? If so, any tricks to ease into the creative headspace?” Stay tuned …

From Doris Lessing‘s acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature:

Writers are often asked: How do you write? With a word processor? An electric typewriter? A quill? Longhand?

But the essential question is: Have you found a space, that empty space, which should surround you when you write?

For more of Lessing’s acceptance speech: In search of the imaginative space: wise words from Doris Lessing.

Also relevant: An amazing writer at work … my blog post on the daily routine of power-writer Joyce Carol Oates.

{Illustration at top is from “A Most Delicate Art” at BibliOdyssey.}

September 7, 2014

Sweet as a … cow? Historical simile searches on Books Google

The “flowering” stage of the writing process is a pleasure. I love making historical simile searches on Google. Such a search can provide a sweet detail for a historical scene, that telling detail that reminds the reader that we’re in another world.

1) Go to Google and type the lead-in to the simile in quotes. For example, “as sweet as a”.

2) Under More select “books.”

3) Click Search tools, and select the time period you want. I select “custom” and type in between 1600 and 1800.

Here are the treasures that resulted, images that tell you quite a bit about daily life hundreds of years ago.

as sweet as a Parsnip

as sweet as a Nut

as sweet as a Cow (!)

as sweet as a Jordan almond

as sweet as a Lark

as sweet as a Pistack Nut

(smelled) as sweet as a nosegay

(smelled) as sweet as a per- fum’d Spanish Glove

as sweet as a wild Fig

as sweet as a thin syrup

Her Breath is as sweet as a young Fawn’s

Her Breath is as sweet as a Grecian Captain. (?)

And, of course, a rose.

Here are some more:

as slender as a Crow’s- quill

as hungry as a Church-mouse

as hungry as a hawk

as tall as a May-pole

as tall as a wild-Goat

as small as a cobweb

as big as a Goose’s egg

I find these simply delightful.

Some recent posts to Baroque Explorations, my research blog:

Happy 376th birthday, Louis XIV!

Honey, figs and red dove feet: cosmetic secrets of the Middle Ages

September 6, 2014

How to approach a writer for a review or testimonial of your book

I often receive email pitches from publicists, asking for a testimonial—a “blurb”—or offering to send me a book to review or mention on this blog. (My little blog!)

Recently, there were two on the same day. One was a model of a successful pitch, and the other an example of what not to do.

I’ll begin with the NOT:

The letter begins: I’m are writing to you about …

Say no more!

The second publicist knew my work and had chosen to approach me for a reason. She included a short description of the book, several glowing blurb quotes, plus a Q&A with the author. It was enough to get me interested.

I only wish publicists would also include an attachment of the opening pages of the novel. That would be all I need to judge if a book might be one I’d like.

That said, I rarely accept. As for all writers, I have a frightening pile of books I am supposed to be reading. Plus, I’m slow: the last WIP I agreed to read for a very good friend took me over a month, even reading it every day.

It takes quite a bit of time to read a novel, so an indication of a book’s length is important, as well as the deadline, should a quote be needed before publication.

What to include

In summary, a pitch for a quote or review should include:

why the book might be of interest to me

the opening pages

the cover

the deadline (if applicable)

book length

Nice extras would be:

publication details (i.e. promotion plan, print run)

advance review quotes, if there are any

a Q&A with the author

Follow-up!

Later, as a courtesy, an autographed copy of the published book should be sent with thanks to those who have taken the time to read and craft a testimonial or review. An appreciative note from the author is always nice. It’s surprising how rarely this is done. I understand! It’s expensive, for one thing, but most of all, it’s time-consuming.

Come to think of it, I’ve yet to finish sending out my own “thank you” copies of The Shadow Queen. (Reminder to self: do it today.)

September 4, 2014

Sentence Swoon: the wonderful Laurie Colwin

What I love most in a novel are bright, witty sentences.

Here is one from the delightful novel Happy All the Time by Laurie Colwin:

To ward off the cold, she wore as a cape what looked like a series of horse blankets with exposed seams. In the yarn shops, she did business briskly. Otherwise, she was a study in manifest chaos.

“Manifest chaos”: c’est moi.

This novel is one of few I’ve reread. If you are in the mood to be charmed by a love story with a difference, I highly recommend it. Actually, it’s two love stories, and what’s different about them is that the women are selfish cads and the men emotional wrecks who fall at their feet in worship of every little nasty thing they say. Refreshing! And very, very sweet.