Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 83

November 25, 2022

ark head

One mental model for this condition is what I call ark head, as in Noah’s Ark. We’ve given up on the prospect of actually solving or managing most of the snowballing global problems and crises we’re hurtling towards. Or even meaningfully comprehending the gestalt. We’ve accepted that some large fraction of those problems will go unsolved and unmanaged, and result in a drastic but unevenly distributed reduction in quality of life for most of humanity over the next few decades. We’ve concluded that the rational response is to restrict our concerns to a small subset of local reality — an ark — and compete for a shrinking set of resources with others doing the same. We’re content to find and inhabit just one zone of positivity, large enough for ourselves and some friends. We cross our fingers and hope our little ark is outside the fallout radius of the next unmanaged crisis, whether it is a nuclear attack, aliens landing, a big hurricane, or (here in California), a big wildfire or earthquake. […]

… it’s gotten significantly harder to care about the state of the world at large. A decade of culture warring and developing a mild-to-medium hatred for at least 2/3 of humanity will do that to you. General misanthropy is not a state conducive to productive thinking about global problems. Why should you care about the state of the world beyond your ark? It’s mostly full of all those other assholes, who are the wrong kind of deranged and insane. At least you and I, in this ark, are the right kind of deranged and insane. It’s worth saving ourselves from the flood, but those other guys can look out for themselves.

I think this is largely true, but I think some other things as well — primarily that any such retreat-to-the-ark is an inevitable response to the inflexible limits of our Dunbar’s Number minds.

“That’s perhaps the way out — keep trying to tell stories beyond ark-scale until one succeeds in expanding your horizons again.” Nope. We don’t need our horizons expanded, we need our attention narrowed and focused.

November 24, 2022

Another book to read:

Gal Beckerman, too, is interested i...

Gal Beckerman, too, is interested in political talk. His new book, The Quiet Before, is essentially a history of conversation, beginning in seventeenth-century France and ending in modern-day Cairo, Charlottesville, Miami, and Minneapolis. Beckerman concentrates not on the revolutionary moment, though — the capture of the Bastille, say, or Fidel Castro’s triumphant arrival in Havana — but on the antecedents of transformative political change. “The incubation of radical new ideas,” he writes, “is a very distinct process with certain conditions: a tight space, lots of heat, passionate whispering, and a degree of freedom to work toward a common, focused aim.”

The conversations that he documents occur not just in person — indeed, rarely in person — but through letters, petitions, newspapers, manifestos, samizdat journals, and feminist zines. And they take place, these days, on social media. Whether this constitutes a continuation of the radical tradition or its negation is a — perhaps the — crucial question that Beckerman explores. We know of the Twitter ranters, Facebook trolls, and Instagram influencers, but where are the passionate whisperers of today?

Rules: A short study of what we live by by Lorraine Dasto...

Rules: A short study of what we live by by Lorraine Daston | Book review:

All history is, it would seem, the history of regulative struggles. After surveying two thousand years of western civilization, and reconstructing battles between manic regulators and recalcitrant regulatees in fields ranging from monasticism through cookery to astronomy and military tactics, Daston is able to discern a few long-term trends. In the beginning, she finds, rules tended to be “thick”, in the sense of being replete with examples, observations and exceptions; but with the passage of time they have grown thinner and thinner and are now approaching the extreme etiolation of the absolute algorithm. At the same time rules that used to be flexible have become more and more rigid, and the specificity of old-world regulations has been replaced by universality, or rather – as Daston surmises – by the pretence or illusion of it. Behind all of these changes she notices a larger one, in which rules have followed a “rough historical arc” that leads from an ancient world of “high variability, instability and unpredictability” to a modern one in which we all tend to assume, without much justification, that “the future can be reliably extrapolated from the past, standardisation ensures uniformity, and averages can be trusted”.

This is fascinating. I don’t know what to do with it, except read the book, but it’s fascinating.

A German map of the Valley of the Kings, from the Bodleia...

A German map of the Valley of the Kings, from the Bodleian Map Room Blog.

November 23, 2022

the media ecology of college writing

Practically speaking, GPT-3 and the like demand that educators reconsider the writing process in fundamental ways. Symons entertains the possibility of returning to handwriting; other commentators have suggested collecting drafts at multiple stages and perhaps tweaking the assignment between drafts. Educators are now administering the Turing test in reverse: What are questions that only humans can answer well? What kinds of thinking does writing make possible for us?

In 1987, Flusser worried that AI would outstrip human writers, assuming responsibility even for the recording of history. The current crop of AIs pose no such threat, since they are not autonomous understandings but dynamic reflections of human-built textual culture. Their danger lies instead in short-circuiting the development of human writers, at least if educators fail to adapt to our new media ecology in which the medium can compose humdrum messages on demand.

My dear friend Rick is precisely correct. Some years ago, when I noted the dramatic increase in professors’ use of services like Turnitin, it seemed obvious to me that students and teachers in the humanities — or rather, students and teachers as puppets of a parasitical online ecosystem of “educational services” — were entering a kind of arms race, and one that could never have a winner. I also saw that the entire arms race was made possible by the overwhelming dominance of one particular assignment: the research paper. And then I asked a question: What if I stopped assigning research papers?

After all, my goal is not to make my students better writers of research papers. My goal is to help them grow more skilled and more confident as readers, writers, and reasoners. (My proximate goal, anyway; I have deeper aspirations for the enriching of their humanity, but those are better described as hopes than as goals.) If the dominance of this one genre is actually impeding my pedagogical purposes, then wouldn’t it be wise for me to look for other kinds of assignment that could enhance my students’ reading, writing, and reasoning without getting us all sucked into that arms race?

I’ve been giving unusual writing assignments my whole career, but not in all my classes. When I taught literary theory I always had my students write dialogues, in each one ventriloquizing two major theorists; in some classes I’ve had students build websites; in others I’ve had them prepare critical editions of texts, with introductions and annotations. But until fairly recently I felt an obligation to teach the good old research paper in at least some classes. Around 2016, I think, I ceased to feel that obligation. I haven’t assigned a research paper since, and I don’t expect ever to assign another one.

Pretty soon, I think, my entire profession will need to go through a process of reconsideration similar to the one I’ve already been through.

China wants to change, or break, a world order set by oth...

China wants to change, or break, a world order set by others | The Economist:

Nor does Mr Xi accept that the second world war created a mandate to draw up a liberal order. A China/EU summit in April was clarifying. The European Council president, Charles Michel, explained why Europe’s dark past, notably the Holocaust, obliged its leaders to call out rights abuses, from China to Ukraine. According to a readout shared with EU governments, Mr Xi retorted that the Chinese have even stronger memories of suffering at the hands of colonial powers. He cited treaties forcing China to open markets and cede territory in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and racist bylaws banning Chinese people and dogs from parks in European-run enclaves. Mr Xi recalled the massacre of civilians at Nanjing by Japanese invaders in 1937. Such aggression left the Chinese with strong feelings about human rights, he said, and about foreigners who employ double standards to criticise other countries.

Hard to deny that they have a point. Hard also to deny that they’re trying to make way for permanent tyranny.

Many developing countries see nothing magic about the year 1945, and have limited nostalgia for a time when the West dominated rulemaking. China is ready to offer them alternatives. Seven decades ago, at founding meetings of the un, Soviet-bloc delegates sought an order that deferred to states and promoted collective rather than individual rights, opposing everything from free speech to the concept of seeking political asylum. In the late 1940s communist countries were outvoted. China now seeks to reopen those old arguments about how to balance sovereignty with individual freedoms. This time, the liberal order is on the defensive.

The Economist is doing great work on China these days. Their podcast series about Xi Jinping, The Prince, was outstanding — a kind of survey of recent Chinese history through the story of one man. And their new newsletter on China, Drum Tower, which is accompanied by a podcast, promises to be excellent also.

Michelle Nijhuis:

Speakers of Luganda, the most common in...

Speakers of Luganda, the most common indigenous language in Uganda, don’t have a word for “depression.” They use the terms yo’kwekyawa and okwekubazida, which roughly translate as “self-loathing” and “self-pity” and describe two distinct conditions; the former, which can include thoughts of suicide, is considered more severe. In Zimbabwe in the 1990s, researchers learned that the local Shona language had one word for everyday sadness (suwa) and another for a persistent, ruminative state that fit the clinical description of depression. This term, kufungisisa, which literally translates to “thinking too much,” unlocked communication between practitioners and patients.

In the early 2000s the Zimbabwean psychiatrist Dixon Chibanda recognized that his rural patients, many of whom were severely stressed by poverty and the multifold impacts of the HIV epidemic, were dying from a lack of mental health care. He recruited a corps of rural community members, predominantly grandmothers, and trained them to conduct informal therapy sessions with their neighbors on open-air “friendship benches.” In clinical trials, the grandmothers and their benches proved to be so successful in relieving the most incapacitating symptoms of depression that the approach has since spread to Kenya, Botswana, the Caribbean, New York City, and elsewhere.

November 22, 2022

a change of attention

After the killing of George Floyd, my first response — after sympathy for poor Floyd, I hope — was to think that the protesters were overreacting to an event that, while tragic, was not nearly as common as they were saying. (No, there’s no “Black genocide” in America.) But then I started noticing the response of many white conservatives: an opposite exaggeration, in their case of the dangers of protests; a noticeable lack of sympathy for the victims of police violence, and a tendency to blame those victims; and in general a disinclination to see racial prejudice as a meaningful element of American culture.

I wrote a few posts about all this, including one about the difference between acute and chronic suffering.

Similarly, when the whole controversy over Critical Race Theory blew up, my first reaction was dismay at the ways that “activists” were using shoddy scholarship, or wholly bogus pseudo-scholarship, to implement a radical political agenda for America’s schools. But then, again, the white conservative pushback was both uncharitable and extreme, and seemed determined to treat any reckoning with America’s history of slavery and racism as “CRT” and therefore to be banished. Increasingly, white conservatives took up the view that explicit declarations of hatred for people of a certain color is the only kind of racism there is.

This struck me as just as historically as blinkered and uninformed as, I dunno, maybe the views of the Black Hebrew Israelites. So, me being me, I started thinking about the past, listening to the voices of our ancestors — in this case mainly recent ones, which in my view is okay, because they always have a strong gravitational pull, and anyway people think that anything that they haven’t thought about in the past 72 hours is ancient history and therefore irrelevant. Ralph Ellison is as much a mystery to them as Homer.

But I’ve been reading Ralph Ellison — a lot of Ralph Ellison, letters and essays; and that led me to Murray’s dear friend Albert Murray, whose curious and wonderful body of work I’m seriously into. (After all, Murray is my fellow native of Alabama.) There’s a tradition of thought and expression here that seems deeply relevant to the current scene, capable of illuminating much that otherwise remains dark for us.

I posted a couple of passages relevant to all this stuff in a recent newsletter, and fifty or sixty people immediately unsubscribed. Okay, well, I guess that’s not really what my newsletter is about, so fair enough. But heads up: Here at the old blog you’ll be hearing more about some of the leading Black intellectuals of the past half-century or more. Because they’re fascinating in themselves — and they tend to illuminate our own weird moment.

So my thanks to white conservatives for leading me into this fertile field of reading and thinking. I owe you, guys.

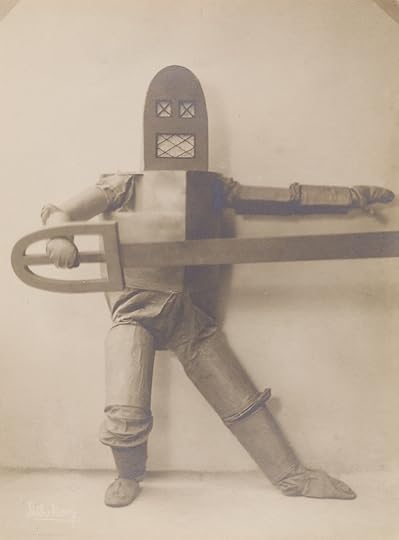

Tanzmasken

Definitions:

An accurate definition of “influencer” ...

An accurate definition of “influencer” is: a virtuoso of a particular internet platform; someone who has learned to use its mechanisms to achieve their own objectives, rather than the other way around.

An accurate definition of an internet “creator” would have to be: someone whose income is determined by a platform’s algorithms.

That’s Robin Sloan, with a very good distinction. I’m not either of those things, so I wonder what I am? Maybe just a writer.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers