Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 73

January 13, 2023

the Christian and the hearth

In traditional Roman culture, the focus, the hearth, is all about holding the family together: the family is the essential, immutable, and foundational unit of civilization. What the Romans called the dignitas marriage — as opposed to the concubinatus union, which was merely a formalizing of a sexual relationship. — was meant to ground all the larger elements of the social order. (The young Augustine, as he explains in his Confessions, had a concubinatus relationship while he was waiting for his parents to organize a dignitas marriage for him, and he and his concubine were alike heartbroken when told that their union had to be broken.) Thus the legal, and not just the social, dominance of the paterfamilias — his patria potestas.

As Carle Zimmerman shows in his seminal Family and Civilization, the Christian church, when it emerged as a force in Roman society, complicated the simple duality of the Roman system. Bishops and priests denounced the concubitanus marriage: legally, it had to be dignitas or nothing. But even dignitas marriage was insufficient, in that it was merely personal and social: true Christian marriage is sacramental, and an image of the relationship between Christ and his church. What the marital family was in secular legal terms came to matter less than what it was in the eyes of God — and the eyes of canon law. (As Zimmerman explains, when in the late-antique and early-medieval world political order grew more fractured and tenuous, this only intensified the power and authority of the Church over the family.) Thus was inaugurated the close connection between the family and the Church that persists in various ways even today.

There’s absolutely no question, as I have said many times on this blog and elsewhere, that if Western society is going to be restored and renewed, such restoration and renewal will need to begin in the family. Everything about our system of metaphysical capitalism is built around detaching people from both the comforts and the obligations of family. If you have sustained a healthy family in our current environment you have done something pretty special, and achieved it against heavy odds.

All that said, and I’m not taking any of it back, Christians really can’t have a straightforward relationship to family. We can’t simply be Romans, even Christianized Romans. There’s this countervailing force in Christian tradition and practice that has to be accounted for. Jesus says that unless you hate your own mother and father, you cannot be a follower of his (Luke 14:26). Jesus says that foxes have holes and birds have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head (Matt. 8:20). Jesus left his home and his family in order to proclaim the kingdom of God, and then to suffer and die; most if not all of his apostles did the same. Saul of Tarsus did not remain in Tarsus, nor did he even remain in Jerusalem, the place that he came to be educated. In the service of the Gospel, he traveled all over the Mediterranean, and died, we believe, in Rome. It was said of Christian missionaries back in the day that they went to the mission field carrying their coffins on their backs – that is, they planned never to return to what had been their home, but to live out their lives in strange lands, so that they could tell people about Jesus.

And of course Jesus never married; not did Paul, whose attitudes towards marriage were notoriously complex. “Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the church” (Eph. 5:25); but the celibate life is superior (I Cor. 7:7). Neither Jesus nor his last apostle were hearth-and-home types, it seems.

This is why I’ve always slightly hesitant about the project of the Front Porch Republic folks. What they are doing is admirable in so many ways, and yet I worry that they could inadvertently foster a kind of idolatry of place. However wonderful and essential home and family are for almost all of us, the Christian has to be willing to give both of those up in order to follow Jesus. We won’t necessarily be able to do that following in our home towns, though perhaps most Christians will be granted that privilege.

There is then something inevitably cosmopolitan about Christianity, not in the sense that the Christian is at home everywhere but in the sense that the Christian can’t be fully at home at home anywhere, given that our citizenship is not of this world (Phil. 3:20). Our primary loyalty must be to the City of God, and not to the City of Man.

I don’t know how to sort all of this out, but I do know that it makes the business of cultivating focal practices complicated for the Christian. What do the practices of the hearth have to do with the Christian life? And how can a Christian pursue focal practices if she doesn’t have a hearth to return to at the end of the day? No, the essential focal practices of the Christian will have to be something more, and maybe other, than the Roman ones. What are the necessary focal practices for a pilgrim people?

Richard Gunderman:

Thanks to [Lillian] Gilbreth, workers ...

Thanks to [Lillian] Gilbreth, workers would be treated not as cogs in a machine, but as people. So great was her compassion for workers that she devoted much of her career to improving the work and home life of persons with disabilities, a population that had exploded as a result of World War I injuries. This required, for example, studying special challenges faced by the blind in performing routine tasks, developing curriculum for teachers of the blind, teaching the blind themselves, and finding opportunities for the employment of the blind in industry. Taylor might have branded such workers inherently inferior, but Gilbreth concentrated on enhancing their capabilities to contribute.

This concern for the worker as a human being instead of an economic tool expressed itself in many practical forms. With Frank, she improved lighting conditions for workers, thus reducing eye strain, and introduced regular breaks throughout the workday. She installed suggestion boxes in the workplace, so the voices of workers would be heard. She required employment contracts to be signed by representatives of both management and organized labor. And when she became the first woman engineering professor (1935) and later the first woman to be promoted to full professor at Purdue University (1940), she focused her considerable energy on opening up careers for women.

This is a fascinating essay — until reading it I knew nothing about Filbreth, whereas I know a good but about her demonic opposite, Frederick Winslow Taylor. That may say something about me, but it also says something about the culture of labor in this country over the past century.

John Warner:

Many are wailing that this technology spells...

Many are wailing that this technology spells “the end of high school English,” meaning those classes where you read some books and then write some pro forma essays that show you sort of read the books, or at least the Spark Notes, or at least took the time to go to Chegg or Course Hero and grab someone else’s essay, where you changed a few words to dodge the plagiarism detector, or that you hired someone to write the essay for you.

I sincerely hope that this is the end of the high school English courses that the lamentations are describing because these courses deserve to die, because we can do better than these courses if the actual objective of the courses is to help students learn to write.

January 12, 2023

allegory of … something

January 11, 2023

El Pintador – An artist in your pocket:Simply tell El Pin...

El Pintador – An artist in your pocket:

Simply tell El Pintador what you would like to see and watch as the AI generates beautiful new art right before your eyes.

You know what I want to see? Something I didn’t know I wanted to see until an actual artist came up with it.

one more word on Kael

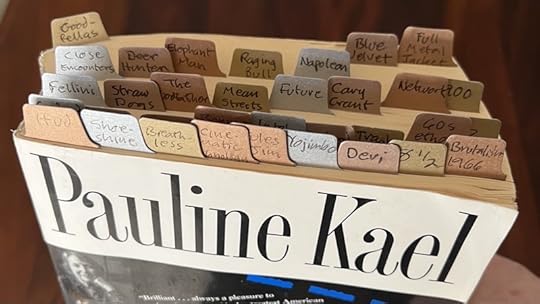

That’s my copy of Pauline Kael’s For Keeps, the enormous collection of the essays on and reviews of movies that she most wanted to preserve. It’s pretty marked up, because Kael, more than any other film critics, helps me to understand what I think about movies. Re: my three categories of thinker, Kael is neither a good Explainer nor a reliable Illuminator — nothing in Renata Adler’s notorious takedown of Kael is wrong, exactly, even if it relies far too heavily on strategic omission — but she’s one hell of a Provoker.

You’ll notice how much how many more markers there are in the early pages then there are in the later ones. This has something to do with my own interests, but I think it has a lot more to do with how Kael’s relationship to the movies changed over the decades. This first occurred to me as I was reading her review of Blade Runner, which is a largely hostile one … but the hostility really wasn’t, for me, the problem (especially since that initial theatrical release of the movie is indeed badly flawed). Rather, while reading I just felt that Pauline Kael was not made to be reviewing movies like Blade Runner, that by this point the movies had a traveled down a path that was simply alien to her sensibility.

She was still capable of having intense responses to movies, positive ones as well as negative. For instance, there’s a scene in My Left Foot that she says might be the most emotionally wrenching she had ever seen in movies. (Any of you who have seen My Left Foot will know precisely the scene that she’s talking about.) So it’s not as though she had come to hate new movies; she thought that some were good and most were not so good, and that was no different in the Eighties than it had been in earlier decades. But it is pretty obvious that her intellectual and aesthetic formation is not really suited to the direction that movies take from the Eighties onward.

She retired in 1991, largely because of the onset of Parkinson’s disease, which some people think may have affected her mind. I don’t know about that, but certainly many of the reviews that she wrote in the Eighties were indistinguishable from the work of other critics. That was almost never true of her earlier work, which was sometimes right and sometimes wrong, sometimes exhilarating and sometimes exasperating, but it was all very obviously written by Pauline Kael and could not have been written by anyone else.

I think maybe she might’ve retired a decade too late; but she certainly should have gotten started a decade earlier. She really only started publishing regularly in her forties, and didn’t commence her regular column for the New Yorker until she was fifty. If her talents had been recognized earlier she could have taken over for James Agee, who was only a decade older than her, as the most important American writer about film. It would’ve been wonderful to get Kael’s real-time takes on the films that emerged from the late Forties to the late Fifties.

In 1969 Kael wrote a long essay for Harper’s called “Trash, Art, and the Movies” that I’m going to return to in another post — it helps me think about what I was talking about in yesterday’s post — but I’ll leave you with a passage from it that’s classic Kael, and that shows you what we’ve been missing in writing about movies since she left the scene:

A good movie can take you out of your dull funk and the hopelessness that so often goes with slipping into a theatre; a good movie can make you feel alive again, in contact, not just lost in another city. Good movies make you care, make you believe in possibilities again. If somewhere in the Hollywood-entertainment world someone has managed to break through with something that speaks to you, then it isn’t all corruption. The movie doesn’t have to be great; it can be stupid and empty and you can still have the joy of a good performance, or the joy in just a good line. An actor’s scowl, a small subversive gesture, a dirty remark that someone tosses off with a mock-innocent face, and the world makes a little bit of sense. Sitting there alone or painfully alone because those with you do not react as you do, you know there must be others perhaps in this very theatre or in this city, surely in other theatres in other cities, now, in the past or future, who react as you do. And because movies are the most total and encompassing art form we have, these reactions can seem the most personal and, maybe the most important, imaginable. The romance of movies is not just in those stories and those people on the screen but in the adolescent dream of meeting others who feel as you do about what you’ve seen. You do meet them, of course, and you know each other at once because you talk less about good movies than about what you love in bad movies.

January 10, 2023

truth

“Oh, it’s so hard to be good under the capitalistic system.” — Genevieve Larkin (Glenda Farrell) in Gold Diggers of 1937

greatness in film

The 2022 Sight and Sound critics’ poll of the greatest films of all time featured a surprising Number One: Chantal Akerman’s 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. I had never watched it, and it’s on the Criterion Channel, which I subscribe to, so I had to watch, didn’t I? I did, and here are my thoughts:

It’s a tract. It’s a powerful tract, but it is purely polemical. It has one message and one mood. The one mood is used to drive home the one message with relentless force; there is no possibility of dissent or even ambivalence. It is not a melodrama, but it is like melodrama in the sense that it allows but a single emotional response. I think that the film is a powerful statement, but is not a great work of art; maybe not a work of art at all.

Now, being a great work of art is not the only thing that a movie, or even a novel or a poem, might aspire to. There are many other worthwhile goals to pursue. But I think that one of the vital contributions that truly major works of art make to our common life is their depiction of situations to which equally intelligent and equally reasonable people might have different responses. In our moment — in which social media have conspired to promote and celebrate the unambiguous taking of sides about everything, this contribution is not recognized as having any value. So of course our critics have chosen as their top film one that disdains such complexity. (Also: Vertigo almost repeating its 2012 top finish? Sigh.)

When Jean Renoir’s film The Rules of the Game appeared in 1939, the opening audience hated it. Renoir was shocked and troubled by this response, and took the movie back to the editing room, where he cut out 23 minutes. As Christopher Faulkner explains in a short video on the Criterion Channel, one of the chief effects of the cuts was to make the character he himself played, Octave, a much less complex one – far more straightforwardly craven and selfish than he is in the original film. Renoir inexplicably axed a key scene in which Octave’s struggle between self-gratification and generosity is resolved in favor of generosity.

But when the film was restored to its original length — or possibly something a little longer — in 1959, the complexities of Octave were restored. And that is when The Rules of the Game became a truly great movie. Its greatness lies in the richness of its portrayal of this morally compromised world of the French aristocracy. Morally compromised, yes, but not completely without self-knowledge, not completely without standards. (Most of the “rules of the game” are meant to enable hypocrisy … but not all of them.) When you watch the film in its full version, you have a conflicted response to Octave, in very much the same way that you have conflicted responses to many people you know. For one thing, it is Octave’s generosity that results in the death of his friend — had he given in to his selfish impulses he himself would have died. The ironies are multiple and profound. But in the shorter version, we see merely the corruption of the aristocracy — we receive a single message and a single permissible viewpoint. And that is why the shorter version is a dramatically inferior film to the longer one.

In his book about Shakespearean comedy — still, I think, the best thing yet written about those plays — Northrop Frye talks about Shakespeare’s habit of creating characters who are excluded, or perhaps exclude themselves, from the festive reconciliation which the other characters at the end of the play enjoy.

The sense of festivity, which corresponds to pity in tragedy, is always present at the end of a romantic comedy. This takes the part of a party, usually a wedding, in which we feel, to some degree, participants. We are invited to the festivity and we put the best face we can on whatever feelings we may still have about the recent behavior of some of the characters, often including the bridegroom. In Shakespeare the new society is remarkably catholic in its tolerance; but there is always a part of us that remains a spectator, detached and observant, aware of other nuances and values. This sense of alienation, which in tragedy is terror, is almost bound to be represented by somebody or something in the play, and even if, like Shylock, he disappears in the fourth act, we never quite forget him. We seldom consciously feel identified with him, for he himself wants no such identification: we may even hate or despise him, but he is there, the eternal questioning Satan who is still not quite silenced by the vindication of Job….

Think for instance of Malvolio in Twelfth Night, who is exposed as a strutting, delusionally self-satisfied fool … and yet even the characters who so expose him can seem uncomfortable with what they have done; and we the spectators can’t help but be aware, if only subliminally, that some of those included in that festive circle at the end are not necessarily any better than Malvolio the mocked.

I think this kind of character is absolutely essential to the greatness of Shakespearean comedy, in much the same way that in his best tragedies we see comical characters who are detached from the terrible events that we see unfolding. Think for instance of the gravedigger in Hamlet, who goes about his business regardless of what happens to the prince and the other members of the royal family of Denmark. He is a living embodiment of the point Auden makes in “Musée des Beaux Arts.”

In my view, this complication of our responses, this questioning of our priorities, this reminder that we could see the world in rather different colors than those perceived by the most important characters in the story, is one of the essential gifts great art offers to us. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t a place for the tract, the polemic — the story that gives us a single unambiguous message. It just means that excellence in polemic is different than greatness in art.

Whenever anyone says what I’ve just said, what comes back is a mocking Yes, but is it art? — with the assumption that trying to distinguish between what is and what isn’t is a mug’s game. And maybe it is. But it seems to be one that we mugs can’t stop playing: som elf us have a sense that the term art is not a useless one.

I’m going to pause here, with a note for future reference that the question of what makes a movie great is a more difficult one than I have acknowledged here: see, for instance, this post by Adam Roberts on the unrelenting seriousness of the critics’ choices in the S&S poll. More on all these matters soon. Or eventually.

January 9, 2023

one of the classic blunders

A while back I quoted Amna Khalid’s thoughtful response to the Hamline University kerfuffle; now we have a strong statement from the Muslim Public Affairs Council. It’s not often that you get a big public dispute in which every party on one side of the issue is thoughtful, measured, and well-informed, while every party on the other side gives every indication of being an ignoramus. But here we are.

The Hamline administration has committed one of the classic blunders — right up there with getting involved in a land war in Asia and going up against a Sicilian when death is on the line — and it’s not deciding that certain groups on campus are to be protected from perceived insult while others are left to fend for themselves. That’s bad academic practice, but it’s not one of the classic blunders. The classic blunder here is assuming that the protected group is intellectually unanimous. The leaders of Hamline obviously believed that if one Muslim is offended by something then that thing is ipso facto “offensive to Muslims.” It’s the kind of error you make when you’re a well-meaning lefty who doesn’t know anyone who isn’t also a well-meaning lefty.

Escaping the Malthusian Trap: What an amazing graph-in-mo...

Escaping the Malthusian Trap: What an amazing graph-in-motion by Kieran Healy. Malthus believed that as population in a given locale rises, a point is reached at which food supply can’t keep up, which then leads to a decline in population. And if you look at the early moments of this visualization, you see what the Trap looks like (with the added complication of a severe drop in population as a result of the Black Death). But then things start to change.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers