Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 66

February 22, 2023

plain speaking

Letter to Eric Fenn of the BBC:

Magdalen College, Oxford.

7th May 1943.

My dear Fenn,

Sorry again. But a talk to the general public on Paradise Lost would be an absolute waste of time. What’s the good of telling them they’ll enjoy it, when we both know they won’t?

yours sincerely,

C. S. Lewis

February 21, 2023

Re: this explicit deepening of Pope Francis’s hostility t...

Re: this explicit deepening of Pope Francis’s hostility to trad Catholics, let me call attention to something I wrote two years ago.

Grayson Perry, detail from Print for a Politician (click ...

Grayson Perry, detail from Print for a Politician (click to see larger image)

the classics are all right

Re: the recent kerfuffle over the vandalism of Roald Dahl’s books, Walter Kirn tweeted “I ran into two used book stores today and grabbed classics like I was saving them from a fire.” In fact “the classics” are fine — they’re in the public domain and thanks to endeavors like Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive they are unlikely to be disappeared or bowdlerized. If you’re worried about them, just download the ones you most care about and do what you can, when the supersensitives come with their digital X-Acto knives and their infinite smugness, to let people know how to access the originals.

Likewise, living authors are safe: the supersensitives can demand changes to their works but they don’t have to agree. And if they do agree, well, that’s their business. (But if they agree against the prickings of their conscience, shame on them.)

No, the supersensitives have a rather narrow target: dead writers whose works are still in copyright. Those are the ones vulnerable to vandalism — by those who control the copyright.

his harshest critic

I recently re-read Ruskin’s The Seven Lamps of Architecture, in the third edition of 1880. Ruskin had originally published the book in 1849, when he was 30 years old, and though it had proved quite popular, later in life Ruskin was reluctant to authorize a new edition. His reason? He hated the book.

He finally gave in, but insisted to the publisher that he be given the opportunity to annotate it. The resulting ongoing ill-tempered commentary is very entertaining.

Even when he liked what he had written, he could be cynical. For instance, he approved of the glorious and justly famous passage in which he repudiates the tearing down of old buildings:

Of more wanton or ignorant ravage it is vain to speak; my words will not reach those who commit them, and yet, be it heard or not, I must not leave the truth unstated, that it is again no question of expediency or feeling whether we shall preserve the buildings of past times or not. We have no right whatever to touch them. They are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them, and partly to all the generations of mankind who are to follow us. The dead have still their right in them: that which they laboured for, the praise of achievement or the expression of religious feeling, or whatsoever else it might be which in those buildings they intended to be permanent, we have no right to obliterate. What we have ourselves built, we are at liberty to throw down; but what other men gave their strength and wealth and life to accomplish, their right over does not pass away with their death; still less is the right to the use of what they have left vested in us only. It belongs to all their successors. It may hereafter be a subject of sorrow, or a cause of injury, to millions, that we have consulted our present convenience by casting down such buildings as we choose to dispense with. That sorrow, that loss, we have no right to inflict.

On the phrase “my words will not reach those who commit them” the older Ruskin wrote, “No, indeed! — any more wasted words than mine throughout life, or bread cast on more bitter waters, I never heard of. This closing paragraph of the sixth chapter is the best, I think, in the book, — and the vainest.”

But he is rarely as kind to himself. Of a passage on the Gothic architecture of Venice he noted, “I have written many passages that are one-sided or incomplete; and which therefore are misleading if read without their contexts or development. But I know of no other paragraph in any of my books so definitely false as this.” And one of the funniest moments comes in response to a passage about neo-Gothic architecture, which was just getting started in 1849:

The stirring which has taken place in our architectural aims and interests within these few years, is thought by many to be full of promise: I trust it is, but it has a sickly look to me.

Ruskin’s comment in 1880:

I am glad to see I had so much sense, thus early; — if only I had had just a little more, and stopped talking, how much life — of the vividest — I might have saved from expending itself in useless sputter, and kept for careful pencil work! I might have had every bit of St. Mark’s and Ravenna drawn by this time. What good this wretched rant of a book can do still, since people ask for it, let them make of it; but I don’t see what it’s to be.

This wretched rant of a book — why didn’t I practice drawing instead?

February 20, 2023

John Ruskin, Study of the Marble Inlaying on the Front of...

Albert Murray and me

From my new essay for Comment on Albert Murray’s “blues idiom”:

For white North American Christians who perceive themselves as marginalized, disparaged, despised, maybe even persecuted — well, a road map for that territory is all around us, in the experience of black Americans, especially as formulated by the great Albert Murray. And I think Murray would have been glad to see his work applied in this way: he thought, and said all the time, that the lessons of the blues idiom are universal human lessons. “When the Negro musician or dancer swings the blues, he is … making an affirmative and hence exemplary and heroic response to that which André Malraux describes as la condition humaine.”

The essay is behind a paywall for another month — unless you subscribe to Comment, of course. (Nudge nudge wink wink.) By the way, I love the artwork the editors and designers chose to illustrate the essay, e.g.:

February 19, 2023

Claude Monet, The Museum at Le Havre

Claude Monet, The Museum at Le Havre

February 18, 2023

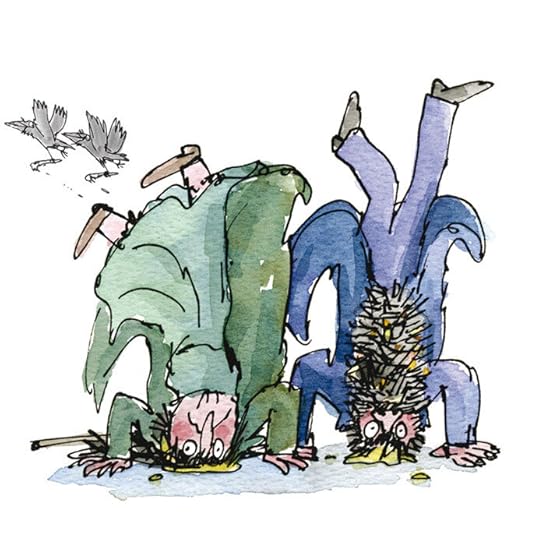

Twits

It’s been widely reported that the U.K. children’s book publisher Puffin is producing a new edition of Roald Dahl’s books with all the wrongthink – or as much of it as possible; this is Roald Dahl, after all – taken out.

Sometimes they’re editing Dahl-as-such and sometimes his characters. The gluttonous Augustus Gloop in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is no longer described as “fat” but rather as “enormous,” thus leaving readers free to imagine that he’s a powerlifter in a high weight classification. Dahl himself is the insensitive one there. When a character says of another character “I’d knock her flat,” Puffin’s supersensitives replace that fierce language with “I’d give her a right talking to.” (But what if the character speaking is the type to use strong language? Or do bad things? Shall we have a version of Crime and Punishment in which Raskolnikov skulks around St. Petersburg fantasizing about giving his landlady a right talking to?)

Sometimes it’s hard to tell what offense the supersensitives imagine: It’s not clear that calling someone a “trickster” rather than a “saucy beast” makes an improvement in manners; what is clear is that the meaning is completely different. But: while Dahl referred to Mrs. Twit as “ugly and beastly,” she is now just called “beastly,” though I cannot imagine why calling someone a “beast” is unacceptable but calling them “beastly” is hunky-dory.

One could go on about this silliness all day, and many are doing so, but I actually think there’s an important point to be made in response to these changes: the people doing it have no right to do so. They have the legal right, but what they’re doing is morally wrong.

It’s morally wrong first of all because it’s dishonest. The books will still be sold as Roald Dahl’s – it is his name that will draw readers to these volumes – but they are in fact Dahl’s involuntary collaboration with people who find some of his words and phrases intolerable. That this is so should be announced on the book’s covers – but you may be sure that it will not be. If you own the rights to Dahl’s books but passionately believe that what Dahl wrote is too offensive for today’s readers to face, then your only honorable option is to stop selling the freakin’ books.

This may sound like an odd digression, but bear with me: I’ve been re-reading The Seven Lamps of Architecture, in which Ruskin confronts the widespread practice, in the England of his time, of either dramatically renovating or tearing down old buildings.

First, Ruskin says, when a building is stripped down to its shell and given an entirely new interior, those who do it should call it what it is: destruction. “But, it is said, there may come a necessity for restoration! Granted. Look the necessity full in the face, and understand it on its own terms. It is a necessity for destruction. Accept it as such, pull the building down, throw its stones into neglected corners, make ballast of them, or mortar, if you will; but do it honestly, and do not set up a Lie in their place.” So also I say: Do not set up a Lie in place of Roald Dahl’s actual books. If they are intolerable, do not tolerate them. Let them go out of print, take the digital editions off the market, and force those of us who are bad enough to desire the books to scour second-hand bookstores for them.

But let’s pursue Ruskin’s argument a bit further. Sometimes a building is torn down altogether, razed to the very ground. What does Ruskin say about that?

Of more wanton or ignorant ravage it is vain to speak; my words will not reach those who commit them, and yet, be it heard or not, I must not leave the truth unstated, that it is again no question of expediency or feeling whether we shall preserve the buildings of past times or not. We have no right whatever to touch them. They are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them, and partly to all the generations of mankind who are to follow us. The dead have still their right in them: that which they laboured for, the praise of achievement or the expression of religious feeling, or whatsoever else it might be which in those buildings they intended to be permanent, we have no right to obliterate. What we have ourselves built, we are at liberty to throw down; but what other men gave their strength and wealth and life to accomplish, their right over does not pass away with their death; still less is the right to the use of what they have left vested in us only. It belongs to all their successors. It may hereafter be a subject of sorrow, or a cause of injury, to millions, that we have consulted our present convenience by casting down such buildings as we choose to dispense with. That sorrow, that loss, we have no right to inflict.

As astonishingly eloquent and impassioned declaration, which, in regard to architecture, one might plausibly disagree with. (Though not easily, I think. I may return to this in another post.) Buildings take up a good deal of space, and the maintenance of them can be expensive; there certainly are circumstances in which demolition is indeed necessary. Ruskin, remember, grants this point, though not without certain hedgings.

But Ruskin’s argument is irrefutable when it comes to the other arts of the past – poetry, story, music, painting, sculpture. There can be no justification for mutilating or destroying them to suit “our present convenience.” We do not know whether later generations will think as we do, will share our preferences and our sensitivities; to preserve the art of the past is to show respect not only for that past but also for our possible futures. And it is to establish a standard for how we wish to be treated by our descendants.

Even the Victorians (and some of their successors) who thought sculptures of naked men too offensive for ladies to see merely covered the pudenda with plaster leaves — the penises themselves remained untouched, for later generations, and less delicate viewers, to see if they wish. (Some years ago I published an essay on this practice — and related matters.)

Perhaps Puffin — since there’s no way in hell they’re gonna give up the chance to make bank — can provide two versions, sort of like like New Coke and Coke Classic, clearly differentiated by label. They could advertise the one and not advertise the other; they could make their preferences clear; they could say “If you are a Good Person you will purchase our sanitized versions rather than the nastiness written by Roald Dahl himself.” And then people could buy the version they want.

Wanna place bets on which version readers would choose? But I don’t think we’ll find out. The one canonical rule of the supersensitives is: The reader is always wrong. Because any genuine reader is, by definition, not a supersensitive.

Inside the Bro-tastic Short-Term Rentals Upending an Aust...

Inside the Bro-tastic Short-Term Rentals Upending an Austin Community:

Almost anywhere you find tourists in Texas, from waterfront neighborhoods on Galveston Island to the ghost towns in the western reaches of the state, locals are bemoaning the changes unleashed by short-term rentals and the visitors who temporarily inhabit them. In Dallas, where one neighborhood STR was turned into a raucous wedding venue, infuriating neighbors, the city council is weighing a plan to outlaw STRs from residential neighborhoods. In Fredericksburg, the popular Hill Country getaway, locals have blamed STRs for exacerbating a severe housing shortage. In Wimberley, about an hour southwest of Austin, they’ve been accused of encouraging debauchery. But when it comes to STRs in Texas, there is no place quite like Austin. The influx of STRs is inextricably linked to the city’s transformation, in just over a decade, from one of the most affordable cities in America to one of the least. Between 2000 and 2010, Austin was the only city in the U.S. experiencing double-digit growth that also saw a decline in the percentage of its Black population — a decline that continued over the next decade. No longer a countercultural haven for artists and independent thinkers, Austin has embraced a new role as the tourist-obsessed, bachelor party–dependent STR capital of Texas — a kind of Las Vegas with tacos in which it can feel as if the real world has been subsumed by the digital one being marketed on Instagram by newly-arrived influencers and real estate agents.

This is incredibly depressing but also utterly unsurprising.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers