Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 53

July 12, 2023

starting from zero

The young architects and artists who came to the Bauhaus to live and study and learn from the Silver Prince talked about “starting from zero.” One heard the phrase all the time: “starting from zero.” Gropius gave his backing to any experiment they cared to make, so long as it was in the name of a clean and pure future. Even new religions such as Mazdaznan. Even health-food regimens. During one stretch at Weimar the Bauhaus diet consisted entirely of a mush of fresh vegetables. It was so bland and fibrous they had to keep adding garlic in order to create any taste at all. Gropius’ wife at the time was Alma Mahler, formerly Mrs. Gustav Mahler, the first and foremost of that marvelous twentieth-century species, the Art Widow. The historians tell us, she remarked years later, that the hallmarks of the Bauhaus style were glass corners, flat roofs, honest materials, and expressed structure. But she, Alma Mahler Gropius Werfel — she had since added the poet Franz Werfel to the skein — could assure you that the most unforgettable characteristic of the Bauhaus style was “garlic on the breath.” Nevertheless! how pure, how clean, how glorious it was to be … starting from zero!

— Tom Wolfe, From Bauhaus to Our House

The new issue of Religion and Liberty features a long essay by Christine Rosen criticizing the we-have-nothing-to-conserve case presented by Jon Askonas in an essay I discuss here and here. Two points from me:

One: Rosen points out that Askonas’s hope for taking power through “a serious program of technological development” is just another version of Mark Zuckerberg’s “move fast and break things” — a model of action which has repeatedly proven much better at destroying than building. Another way to put this is to borrow a phrase from N. S. Lyons and say that the members of several recent post-conservative movements – as exemplified by Askonas’s essay, but also by Patrick Deneen’s call for “regime change,” and by several more extreme calls from some corner of the right to Blow It All Up – tend to be “change merchants”:

Whether an academic, a journalist, a financial analyst, or a software developer, a member of this Virtual class makes his living — and, indeed, establishes his social and economic value — by manipulating, categorizing, and interpreting symbolic information and narrative. “Manipulate” is an important verb here, and not merely in the sense of deviousness. Such an individual’s job is to take existing information and change it into new forms, present it in new ways, or use it to tell new stories. This is what I am attempting to do as a writer in shaping this article, for example.

Members of this class therefore cannot produce anything without change. And they cannot sell what they’re producing unless it offers something at least somewhat new and different. Indeed, change is literally what they sell, in a sense, and they have a material incentive to push for it, since the faster the times are a-changin’ in their field, or in society, the more market opportunity exists for their products and services. They are, fundamentally, merchants of change.

Maybe I shouldn’t include either Askonas or Deneen in this description, because Askonas has walked back his strongest claims, and some reviewers say that Deneen does the same in the latter portions of Regime Change. (I can’t say for sure, because I haven’t yet read it, but the more hard-nosed hard-right critics of the book chastise Deneen for not following through on his more extreme denunciations of the System.) But as a general rule: To be a successful change merchant you have to include, as a necessary prelude to your sales pitch, the claim that nothing you’ll destroy along the way to your innovation is worth preserving. (Starting from zero!) That is, the genuine change merchant will always say that we have nothing to conserve, and the person who genuinely believes we have nothing to conserve will always be either a change merchant or a victim of despair (or maybe both).

Many changes are, of course, necessary, and others are not perhaps necessary but are good or useful or beautiful or all of the above. In my judgment, the people best placed to implement the better kinds of change are not neophiles, who are impatient with anything that exists and desirous to replace it with whatever happens to occur to them, but rather those with a well-founded appreciation for what already exists and from that very appreciation develop a desire to preserve, sustain — and improve. (As Wolfe points out, the neomania of the Bauhaus movement led to a situation in which “Every child goes to school in a building that looks like a duplicating-machine replacement-parts wholesale distribution warehouse.”) One of Burke’s most famous lines is germane here: “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation. Without such means it might even risk the loss of that part of the constitution which it wished the most religiously to preserve.” Conservation and change are not opposites, but, in what that great conservative Albus Dumbledore calls “the well-organized mind,” complementary impulses.

Two: Again, some of those who say that there’s nothing to conserve will qualify that statement when challenged; but there are many among us who think it’s really true. And when I hear that, I find myself thinking about a famous passage from Henry James’s study of Nathaniel Hawthorne:

The negative side of the spectacle on which Hawthorne looked out, in his contemplative saunterings and reveries, might, indeed, with a little ingenuity, be made almost ludicrous; one might enumerate the items of high civilization, as it exists in other countries, which are absent from the texture of American life, until it should become a wonder to know what was left. No State, in the European sense of the word, and indeed barely a specific national name. No sovereign, no court, no personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no country gentlemen, no palaces, no castles, nor manors, nor old country houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, nor abbeys, nor little Norman churches; no great Universities nor public schools — no Oxford, nor Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures, no political society, no sporting class — no Epsom nor Ascot!

It turns out that there’s a certain kind of person who looks at the world we’re living in and thinks: No legitimate government, no useful laws, no worthwhile political acts or actors; no schools, no books, no skills of reading or writing or mathematics or art-making; no charitable organizations that serve people in need; no churches, no inspiring sermons, no beautiful liturgies, no memorable hymns; no national forests and parks, nor well-tended fields; no beautiful architecture, no thriving neighborhoods — no families! Nope. Not a thing to conserve. Those who went before us left us absolutely nothing of value. What can we do but start from zero, says the true change merchant, with me as your guide?

July 11, 2023

academic bullshit

My estimable friend Dan Cohen:

Maybe AI tools can help to combat their unethical counterparts? SciScore seeks to improve the reliability of scientific papers by analyzing their methods and sources, producing a set of reports for editors, peer reviewers, and other scientists who want to reproduce an experiment. Ripeta uses AI trained on over 30 million articles to identify “trust markers” within a paper’s dense text. Using new AI computer vision tools, Proofig takes aim at falsified images within academic work.

But fighting AI with AI assumes a level of care and attention that are increasingly scarce resources in academia. As scholarly publishers will admit, peer reviewers are harder and harder to come by, as journals proliferate and there are greater pressures on the time of every professor. It’s more productive to crank out your own work than to correct the work of others. Professors who are concerned about their students using ChatGPT to create plausible-sounding essays might not look over their shoulders at their own colleagues using more sophisticated tools to do the same thing.

If they — and we — fail to stem the tide of AI-generated academic work, that very work will come into question, and one of the last wells of careful writing, of deep thought, of debate supported by evidence, might be fatally poisoned.

All of Dan’s concerns here are legitimate and serious … but I also think there’s another side to this, at least potentially. I’ve written before about the ways that ChatGPT and the like are revealing the unimaginative, mechanical nature of so many assignments we college teachers create and administer. In that post I wrote, “If an AI can write it, and an AI can read it and respond to it, then does it need to be done at all?“ Might we not ask the same question about our research, so much of which is produced simply because publish-or-perish demands it, not because of any value it has either to its authors or its readers (if it has any readers)?

Countless times in my career I have heard people talk about their need to publish research — to get tenure or promotion — in an AI-like pattern-matching mode: What sort of thing is getting published these days? What terms and concepts are predominantly featured? What previous scholarship is most often cited? And once they answer those questions, they generate the appropriate “content” and then fit it into one of the very few predetermined structures of academic writing. And isn’t all this a perfect illustration of a bullshit job?

Yes, I’m worried about what AI will do to academic life — but I also see the possibility of our having to face the ways in which our work, as students, teachers, and researchers, has become mechanistic and dehumanizing. And if we can honestly acknowledge the conditions, then maybe we can do something better.

July 10, 2023

Little, Big

My friend Adam Roberts wrote recently about John Crowley’s Little, Big, which is (a) one of my very favorite novels and (b) a book I have never written about. I suspect that I’ve never written about it precisely because it means so much to me. One day perhaps I will get to the bottom of this. But for now I just want to make a few comments.

One: Adam thinks the book is a version of baroque, but I don’t think I agree. My inclination is to say that there are forms of elaboration other than the baroque, and Crowley dwells in one of those traditions. His imagination, especially his visual imagination, seems to me to arise from the vision of art that begins with the Pre-Raphaelites, moves on through William Morris, and culminates in the Arts & Crafts movement, which in the first two decades of the twentieth century — the period in which Edgewood was built — was a very big thing in the upstate-New-York world to which Crowley is always drawn. (The Aegypt books are set there too.) Edgewood is surely a house in this tradition, though in its decorated rather than its spare aspect. If you imagine Richard Norman Shaw’s Cragside sitting in a heavily forested corner of the Catskills I think you might envision Edgewood correctly.

Also, the women of Little, Big are often very much in the Pre-Raphaelite “stunner” mode. (Primarily the Elizabeth Siddall cascading-redhead type rather than the Jane Morris darkly-brooding type.) Cf. Rossetti’s The Beloved, which could be a depiction of the enthronement of Daily Alice:

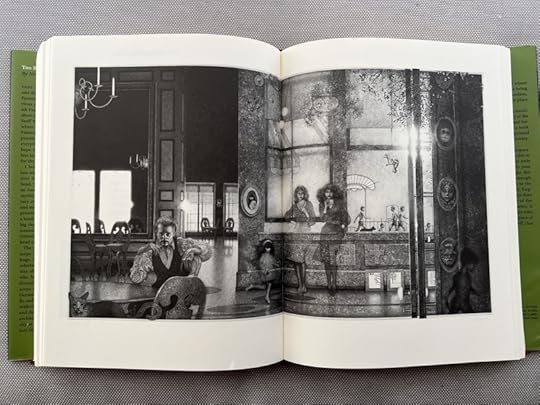

Peter Milton’s illustrations for the rather magnificent 40th anniversary edition of the book capture some of the feel of the novel, though with an Art Deco tinge that might not be elaborate enough:

That’s not wrong, exactly, but I think it’s missing the density of detail present in so many Pre-Raphaelite paintings and William Morris designs, e.g. the Green Dining Room:

I think if you stripped the Pre-Raphaelite visual world of its medievalism — there ain’t no medieval culture here in the Americas — you’d be getting close to the visual aesthetic of Little, Big.

Two: I think almost the whole of Crowley’s imagination — in his fantasies, though not in his many non-fantastic writings — derives from two books, both of them by Frances Yates: The Art of Memory and The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. The first is a book about making the events and experiences and encounters of the past meaningful and coherent; the second is a book about achieving a nirvana, a wholly enlightened consciousness. The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz is re-enacted or re-interpreted several times in Crowley’s work, including the marriage of Smoky and Daily Alice. (Colin Burrow, in an essay that Adam cites, notes this influence and thinks that current scholarly skepticism about Yates’s arguments creates a “big problem” for Crowley’s fiction, though I don’t know why that would be. Surely works of literary art don’t need to be grounded in sound scholarship to be good stories. The discrediting of the Ptomelaic cosmos doesn’t make the Divine Comedy less compelling.)

It may be that Crowley sees us as having to choose between the two visions of Yates’s two books: that is, we can have a history that takes beautiful form or a beatific vision of total Meaning. Those granted nirvana leave their history behind, as the fairies leave behind Edgewood; that it is “a house made of time” is why they must leave it. You could say that Edgewood is the real protagonist of the story because it enables enlightenment for the fairies and for Smoky the completion of his Tale. And so at the end it runs on, telling its story because it doesn’t know how to do anything else, though both of its audiences have departed. I don’t know anything lovelier in literature than the final paragraph of Little, Big, a book that does not begin but rather ends with “once upon a time.”

(There are, I think, three chief sources of image and myth in Crowley’s fantasies: the Arts & Crafts movement, the Rosicrucian Enlightenment, and one more: the counterculture of the Sixties, which I think Crowley sees as, at its best, inheriting those earlier movements — but never quite laying firm hold on them. Swerving from what it could have been and should have been. But that’s more of a theme in the Aegypt books than Little, Big.)

Three: Little, Big is full of Sehnsucht, it is a “search for the blue flower” story, and I don’t know any other book that better depicts this experience. (I don’t agree with Burrow that such a fantasy is “a conscious substitute for the magic in which you don’t quite believe any more”; I think it’s in no way a substitute, but a pointer towards something that necessarily remains always out of reach.) I also think — and this is not unrelated — that Little, Big is an illustration of the fact that for us mortals “death is the mother of beauty”: Smoky’s apprehension of the Tale is shaped wholly by the fact that he will not inherit it, is not made to inherit and inhabit it, but through helping it to come to be he plays a part that only an outsider to its full enactment can play. It is beautiful to him in a way that it cannot be to its participants; that is its gift to him. There is an inevitable asymmetry in his marriage which somehow make it stronger and more wonderful rather than weaker: he loves Daily Alice differently than she loves him. She occupies almost the whole of his short life; he can be to her only a moment, though perhaps the dearest moment, in an endless one. (It is very sweet to me that she and only she knows where he is buried.)

I think by calling attention to this asymmetry he remedies the biggest defect in The King of Elfland’s Daughter: Dunsany never acknowledges that by bringing the whole of Erl into Elfland he has taken away the very thing that makes Lirazel ache for her husband and family: their mortality. Blake’s “Eternity is in love with the productions of time” is the mirror-image of Sehnsucht, and Crowley gets that, while Dunsany, I think, does not.

July 7, 2023

more on SCOTUS and university admissions

Just a few random thoughts about the Harvard opinion. (On this blog I tend to avoid opining on current events, but I am endlessly fascinated by the law, by legal reasoning, and by the various strategies of legal interpretation. As Stanley Fish discovered a long time ago, there’s much overlap between literary and legal interpretation. I caught the bug from him.)

In Sotomayor’s dissent, she describes the majority opinion in this way:

Today, the Court concludes that indifference to race is the only constitutionally permissible means to achieve racial equality in college admissions. That interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment is not only contrary to precedent and the entire teachings of our history, see supra, at 2–17, but is also grounded in the illusion that racial inequality was a problem of a different generation. Entrenched racial inequality remains a reality today. That is true for society writ large and, more specifically, for Harvard and the University of North Carolina (UNC), two institutions with a long history of racial exclusion. Ignoring race will not equalize a society that is racially unequal. What was true in the 1860s, and again in 1954, is true today: Equality requires acknowledgment of inequality.

The problem is that this description is wrong. Indeed, later on she walks some of this back, admitting that “The majority does not dispute that some uses of race are constitutionally permissible. See ante, at 15. Indeed, it agrees that a limited use of race is permissible in some college admissions programs.” So the majority opinion does not demand “indifference to race” (even if Justice Thomas would probably like it to).

But unless I missed it — and I may have; her dissent is lengthy — she doesn’t walk back the baldly false claim that the majority holds to “the illusion that racial inequality was a problem of a different generation.”

Thomas in his concurrence: “I, of course, agree that our society is not, and has never been, colorblind.” Gorsuch in his concurrence: “In the aftermath of the Civil War, Congress took vital steps toward realizing the promise of equality under the law. As important as those initial efforts were, much work remained to be done — and much remains today.” Kavanaugh in his concurrence: “To be clear, although progress has been made since Bakke and Grutter, racial discrimination still occurs and the effects of past racial discrimination still persist.“ (Probably not great for collegiality when one justice forcefully accuses her colleagues of holding views that they have explicitly disavowed. It’s disappointing to see Sotomayor writing in such open disregard for the truth of her statements — but that’s the world we live in.)

Only Roberts, writing for the Court, doesn’t make any such statement, because in his legal reasoning it doesn’t matter. Racial inequality could be better than it used to be, about the same, or worse — it doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is whether the policies employed by Harvard and UNC are legally justifiable. That’s his whole argument.

By contrast, what matters to Sotomayor is that the policies work:

The use of race in college admissions has had profound consequences by increasing the enrollment of underrepresented minorities on college campuses. This Court presupposes that segregation is a sin of the past and that raceconscious college admissions have played no role in the progress society has made. The fact that affirmative action in higher education “has worked and is continuing to work” is no reason to abandon the practice today.

Justice Jackson’s dissent operates under a similar logic: racism is an ongoing social problem, these policies are remedies for racism, therefore these policies are justifiable. But that’s a strange argument for a jurist to make. Many practices work — I could list a thousand tactics police departments have used to reduce crime — but that doesn’t make them legal. So these arguments by Sotomayor and Jackson seem to be outside the scope of their duties. But then, the same is true of Thomas’s dissent, which devotes a great deal of time to arguing that such policies do not work, do not accomplish their goals. That’s actually the chief burden of his concurrence, in which he directs much of his fire towards Jackson: You think policies like this help people like us, but they don’t.

The funny thing about all this is that Harvard and UNC in their briefs and oral arguments explicitly denied that their policies attempt to remediate the consequences of past and ongoing racism — they say that it’s all about creating “diversity.” They did so because SCOTUS precedent wouldn’t have worked in their favor if they had admitted that remediation of injustice is their goal. (Too long a story to get into here.) But the fact that, except for Roberts, the justices largely ignore the explicit justification and instead argue about the role that university admissions play or do not play in remedying injustice indicates that they know what the real reasons for these policies are.

Again and again Sotomayor and Jackson say Racism is bad, why is the majority denying that racism is bad? And again and again the majority say, Of course racism is bad, but our task is not to end racism, our task is to decide this case. (Kagan’s silence on this case is disappointing, since she joined Sotomayor and Jackson, and is an infinitely superior thinker and writer. My guess is that she has her own reasons, quite different from Sotomayor’s and Jackson’s, for dissenting; I’d like to know what they are.)

If even Supreme Court Justices don’t know what their job is, how can the rest of us be expected to? Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has been tweeting that if the court really believed in color-blindness it would have ended legacy admissions. But nobody brought a suit against legacy admissions. Does AOC really think that the Supreme Court can just decree at any time the end of any practice they think unjust? Actually, she might; it’s perfectly possible that she has no idea how the Supreme Court, or the legal system more generally, works. But I think it’s slightly more likely that she’s just performing rage for her social media audience. That’s perhaps to be expected. What’s less expected is for Supreme Court justices to be doing the same thing.

July 5, 2023

forums

As far as how humans connect to one another, what’s next appears to be group chats and private messaging and forums, returning back to a time when we mostly just talked to the people we know. Maybe that’s a better, less problematic way to live life. Maybe feed and algorithms and the “global town square” were a bad idea. But I find myself desperately looking for new places that feel like everyone’s there. The place where I can simultaneously hear about NBA rumors and cool new AI apps, where I can chat with my friends and coworkers and Nicki Minaj. For a while, there were a few platforms that felt like they had everybody together, hanging out in a single space. Now there are none.

To each his own, of course, but after seven or eight years on Twitter — I started in early 2007 — I decided that “everybody together, hanging out in a single space” was a nightmare from which I hoped to awake. It took me a while to awaken completely, but I finally got there, and don’t ever want to go back.

Pierce is wrong about one thing: maybe group chats and private messaging are focused on talking to “the people we know,” but that’s not true of forums, which tend to be built around common interests rather than personal acquaintance. I’m hoping that with all of Reddit’s self-inflicted wounds we’ll get some alternatives, but you know, we could do worse than go back to Usenet.

Actually, I think that would be really cool. I’d love to see a Usenet renaissance, in which case maybe Panic would resume development of their fabulous old Usenet client Unison.

(But yes, I know that there are problems with this idea. But a guy can dream. And there are infinitely fewer barriers to the fixing of open protocols than to the stable, lasting repair of closed ones.)

July 4, 2023

patriotic effusion for Independence Day

I have always, I feel, been somewhat deficient in patriotism — I just don’t have the instinct for it, somehow — but listening to the recent Rest Is History series on the American Revolution got my red-white-and-blue blood up. (I say this, by the way, as a fully paid-up Wang — i.e., member of The Rest Is History Club.) George Washington had wooden teeth (ha ha ha) — Benjamin Franklin went around London “dispensing his wisdom” (ha ha ha) — Aren’t the colonists’ complaints obviously bogus? (ha ha ha) — Why do Americans have a holiday celebrating a press release? (ha ha ha) — Thomas Jefferson is a “phrasemaker” and the American Robespierre … wait, what? I don’t seem to recall Jefferson’s presiding over a Reign of Terror.

In general, I think Brits are the least trustworthy commenters on the United States — in any venue, from the left or the right, I avoid such commentary, because I know it will be filled with overconfident generalizations and smug condescension. Both of those faults arise from the writers’ belief that they have as it were a Special Relationship with the U.S.A. and can therefore interpret it authoritatively. (People from other nations might be even more critical but they are less likely to write or speak from that particular variety of smugness.) I think it telling that when Tom and Dominic did a series on the Irish quest for Home Rule they got an Irishman to guide them — Paul Rouse, who was great — and were highly deferential to his judgments, but when it came time to cover the American Revolution they saw no need for an American perspective.

At the very end there was a brief acknowledgment that George Washington did not become a tyrant when he had the opportunity to do so, and that that’s admirable, but then they immediately went on to talk about his owning of slaves. The overall tone of the episodes converged on a kind of ironic mockery, which I found disappointing not just because I’m an American (I think) but mainly because of its inaccuracy. The leaders of that Revolutionary generation were extraordinary men — it’s almost unimaginable that one moment in history, in so small a nation, would produce figures as prodigiously and variously gifted as Franklin, Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the ever-underrated Madison. (Though Madison was a little too young to have much of a role in the Revolution proper, he was essential thereafter.)

For a better, clearer, juster view, I would recommend John J. Ellis’s excellent Founding Brothers, but even more than that an extraordinary book that is unaccountably out of print: Garry Wills’s Cincinnatus: George Washington and the Enlightenment. No other work that I know of so fascinatingly illuminates the character of George Washington – and the way he was understood by his most thoughtful contemporaries. Thus this statue on the Lawn of the University of Virginia:

Note the fasces, which Washington is about to set aside — you can’t quite see it, but behind him is a plow. If, looking at that statue, you were to turn 180º, you’d see across the Lawn a companion statue, this of a seated Jefferson, gazing contemplatively at Washington — perhaps to admire, but perhaps to make sure Washington does indeed follow the example of Cincinnatus. For it is a model easier to invoke than to imitate.

In this spirit, we might also read an essay from 2021 by my friend Rick Gibson on Washington’s Farewell Address.

Let’s conclude by delivering to these unrepentant monarchists some home truths, as articulated by Jefferson in a letter to John Langdon (1810):

When I observed however that the king of England was a cypher, I did not mean to confine the observation to the mere individual now on that throne. The practice of kings marrying only into the families of kings, has been that of Europe for some centuries. Now, take any race of animals, confine them in idleness & inaction whether in a stye, a stable, or a stateroom, pamper them with high diet, gratify all their sexual appetites, immerse them in sensualities, nourish their passions, let every thing bend before them, & banish whatever might lead them to think, & in a few generations they become all body & no mind: & this too by a law of nature, by that very law by which we are in the constant practice of changing the characters & propensities of the animals we raise for our own purposes. Such is the regimen in raising kings, & in this way they had gone on for centuries. While in Europe, I often amused myself with contemplating the characters of the then reigning sovereigns of Europe. Louis the XVIth was a fool, of my own knowledge, & in despite of the answers made for him at his trial. The king of Spain was a fool, & of Naples the same. They passed their lives in hunting, & dispatched two couriers a week, 1000 miles, to let each other know what game they had killed the preceding days. The king of Sardinia was a fool. All these were Bourbons. The Queen of Portugal, a Braganza, was an idiot by nature & so was the king of Denmark. Their sons, as regents, exercised the powers of government. The king of Prussia, successor to the great Frederic, was a mere hog in body as well as in mind. Gustavus of Sweden, & Joseph of Austria were really crazy, & George of England you know was in a straight waistcoat.

And so on that note: All praise to the Founders, and confusion to degenerate monarchies!

P.S. This is unrelated to the diatribe above, but I can’t resist adding it. Adam Smith, the scholarly guest on the podcast, comments at one point that Benjamin Franklin’s only interest in George Whitefield was in determining the range at which he could project his voice. Franklin was certainly interested in that, but not in that only. Here’s my favorite passage in the whole of Franklin’s Autobiography:

Mr. Whitefield, in leaving us, went preaching all the way thro’ the colonies to Georgia. The settlement of that province had lately been begun, but, instead of being made with hardy, industrious husbandmen, accustomed to labour, the only people fit for such an enterprise, it was with families of broken shop-keepers and other insolvent debtors, many of indolent and idle habits, taken out of the jails, who, being set down in the woods, unqualified for clearing land, and unable to endure the hardships of a new settlement, perished in numbers, leaving many helpless children unprovided for. The sight of their miserable situation inspir’d the benevolent heart of Mr. Whitefield with the idea of building an Orphan House there, in which they might be supported and educated. Returning northward, he preach’d up this charity, and made large collections, for his eloquence had a wonderful power over the hearts and purses of his hearers, of which I myself was an instance.

I did not disapprove of the design, but, as Georgia was then destitute of materials and workmen, and it was proposed to send them from Philadelphia at a great expense, I thought it would have been better to have built the house here, and brought the children to it. This I advis’d; but he was resolute in his first project, rejected my counsel, and I therefore refus’d to contribute. I happened soon after to attend one of his sermons, in the course of which I perceived he intended to finish with a collection, and I silently resolved he should get nothing from me. I had in my pocket a handful of copper money, three or four silver dollars, and five pistoles in gold. As he proceeded I began to soften, and concluded to give the coppers. Another stroke of his oratory made me asham’d of that, and determin’d me to give the silver; and he finish’d so admirably, that I empty’d my pocket wholly into the collector’s dish, gold and all.

George Orwell, review of Mein Kampf (1940):

Nearly a...

George Orwell, review of Mein Kampf (1940):

Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all “progressive” thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security and avoidance of pain. In such a view of life there is no room, for instance, for patriotism and the military virtues. The Socialist who finds his children playing with soldiers is usually upset, but he is never able to think of a substitute for the tin soldiers; tin pacifists somehow won’t do. Hitler, because in his own joyless mind he feels it with exceptional strength, knows that human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades. However they may be as economic theories, Fascism and Nazism are psychologically far sounder than any hedonistic conception of life. The same is probably true of Stalin’s militarised version of Socialism. All three of the great dictators have enhanced their power by imposing intolerable burdens on their peoples. Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a more grudging way, have said to people “I offer you a good time,” Hitler has said to them “I offer you struggle, danger and death,” and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet. Perhaps later on they will get sick of it and change their minds, as at the end of the last war. After a few years of slaughter and starvation “Greatest happiness of the greatest number” is a good slogan, but at this moment “Better an end with horror than a horror without end” is a winner. Now that we are fighting against the man who coined it, we ought not to underrate its emotional appeal.

UPDATE: My friend Adam Roberts thinks that this review may have inspired one of Churchill’s most famous speeches.

George Orwell, review of Mein Kampf (1940):

Nearly all w...

George Orwell, review of Mein Kampf (1940):

Nearly all western thought since the last war, certainly all “progressive” thought, has assumed tacitly that human beings desire nothing beyond ease, security and avoidance of pain. In such a view of life there is no room, for instance, for patriotism and the military virtues. The Socialist who finds his children playing with soldiers is usually upset, but he is never able to think of a substitute for the tin soldiers; tin pacifists somehow won’t do. Hitler, because in his own joyless mind he feels it with exceptional strength, knows that human beings don’t only want comfort, safety, short working-hours, hygiene, birth-control and, in general, common sense; they also, at least intermittently, want struggle and self-sacrifice, not to mention drums, flags and loyalty-parades. However they may be as economic theories, Fascism and Nazism are psychologically far sounder than any hedonistic conception of life. The same is probably true of Stalin’s militarised version of Socialism. All three of the great dictators have enhanced their power by imposing intolerable burdens on their peoples. Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a more grudging way, have said to people “I offer you a good time,” Hitler has said to them “I offer you struggle, danger and death,” and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet. Perhaps later on they will get sick of it and change their minds, as at the end of the last war. After a few years of slaughter and starvation “Greatest happiness of the greatest number” is a good slogan, but at this moment “Better an end with horror than a horror without end” is a winner. Now that we are fighting against the man who coined it, we ought not to underrate its emotional appeal.

July 3, 2023

Would I like to ride on a 1938 London Underground...

Would I like to ride on a 1938 London Underground train? ...

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers