Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 39

December 26, 2023

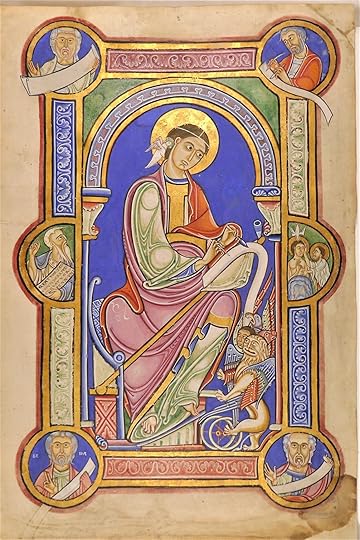

St. John & St. Mark, from the Lambeth Bible

December 22, 2023

Christmas gifts

In introducing the writings of George MacDonald, C. S. Lewis made a fascinating point which can only be quoted at length:

What [MacDonald] does best is fantasy — fantasy that hovers between the allegorical and the mythopoeic. And this, in my opinion, he does better than any man. The critical problem with which we are confronted is whether this art — the art of myth-making — is a species of the literary art. The objection to so classifying it is that the Myth does not essentially exist in words at all. We all agree that the story of Balder is a great myth, a thing of inexhaustible value. But of whose version — whose words — are we thinking when we say this?

For my own part, the answer is that I am not thinking of anyone’s words. No poet, as far as I know or can remember, has told this story supremely well. I am not thinking of any particular version of it. If the story is anywhere embodied in words, that is almost an accident. What really delights and nourishes me is a particular pattern of events, which would equally delight and nourish me if it had reached me by some medium which involved no words at all — say by a mime, or a film. And I find this to be true of all such stories. […]

Most myths were made in prehistoric times, and, I suppose, not consciously made by individuals at all. But every now and then there occurs in the modern world a genius — a Kafka or a Novalis — who can make such a story. MacDonald is the greatest genius of this kind whom I know. But I do not know how to classify such genius. To call it literary genius seems unsatisfactory since it can coexist with great inferiority in the art of words… . Nor can it be fitted into any of the other arts. It begins to look as if there were an art, or a gift, which criticism has largely ignored.

Lewis is prompted to this reflection in part by the fact that MacDonald was not a very good stylist — his prose is often clunky or awkward. But the myths he made were to Lewis extraordinarily powerful. I think that Lewis is right not only about Macdonald but also in his more general point, and that the phenomenon deserves more reflection that it has received.

I may come back to this intriguing idea some day, but I only mention it now because it gives me license to tell briefly, in my own words, one of MacDonald’s stories, “The Gifts of the Child Christ.”

The story centers on a six-year-old girl named Sophy — “or, as she called herself by a transposition of consonant sounds common with children, Phosy.” Phosy’s mother died giving birth to her and her father has recently remarried. He had been in various ways disappointed with his first wife and now he is well on his way to becoming disappointed with his second wife; and he neglects Phosy because she reminds him too much of the wife whom he had lost, and who had not made him happy.

Phosy’s stepmother is pregnant and that means that Phosy is ignored even more than usual; but she doesn’t seem to expect anything else. When at church with her parents she hears a preacher telling the congregation that “whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth,” Phosy wants the Lord to love her and therefore prays that he will chasten her, for this will prove His love. She is too young and too innocent to realize that her life is already a kind of chastening, though one she does not deserve. Phosy becomes obsessed as Christmas draws near with the idea that on that day Jesus will be born — Jesus is somehow born anew each year on Christmas day, she thinks, and she hopes that when he comes again this year he will bring her the gift she so earnestly desires.

So she’s anxious as the day draws near, and her parents are also anxious, but for a different reason: her stepmother’s pregnancy is coming to term. On Christmas morning the stepmother gives birth to Phosy’s little brother, and in all of the stress and anxiety — and, as it turns out, tragedy — of the event, Phosy is completely forgotten. So she dresses herself and comes downstairs and wanders into a spare room of the house … and she sees lying there, alone and still, a beautiful baby boy. It is, she knows, the baby Jesus, come to give her the gift of Himself, and, she devoutly hopes, his chastening also. So she takes the little boy in her arms: he’s perfectly beautiful, but he is also, she realizes, very cold. And so she holds him close to herself to give him her warmth — and it is in this position that her father finds her. And for the first time Phosy weeps. She weeps because there was no one to care for the baby Jesus when he came, and so he died.

It is an extraordinary image that George MacDonald has conjured here, for this is of course a Pieta. It is Mary bearing the body of her dead son, conveyed to us through a small English girl bearing the body of her dead baby brother. Here superimposed on Christmas Day, that most innocently festive of days, is the immense tragedy of Good Friday.

But we do call it Good Friday, do we not?

When Phosy’s father sees her holding her infant brother he sees something in Phosy that he has never noticed before: he discerns the depth and the intensity of her compassion. And he has already been altered in his attitude toward his wife by seeing her grief at the loss of her child. Throughout this story he has only thought of the women in his life as either meeting or failing to meet — though in fact always failing to meet — his expectations; but when he sees his wife and daughter so wounded, their tenderness of heart draws out his own, and a great work of healing begins in this damaged family, a family damaged above all by the absence of paternal love.

“Such were the gifts the Christ-child brought to one household that Christmas,” says MacDonald. “And the days of the mourning of that household were ended.” A knitting up of their raveled fabric begins, and the extraordinary thing is that the chief instrument of that mending is death: the death of Jesus as a man on a cross, or the death of Jesus as an infant in Victorian London, it is one Sacrifice. This is what Charles Williams pointed to when he wrote that the Christian way is “dying each other’s life, living each other’s death.”

In his beautiful book Unapologetic Francis Spufford has Jesus say, “Far more can be mended than you know.” And this is what “The Gifts of the Child Christ” tells us also. George MacDonald made for himself a personal motto — an anagram of his name, imperfectly spelled because in this world things that are mended still show the signs of their frayed or broken state. Mended but not yet perfected are the things and the people of this world, at their very best. MacDonald’s motto was:

The richest of Christmas blessings to you all.

December 20, 2023

The Morgan Beatus Manuscript

December 19, 2023

Brian Eno, from a 1995 diary entry:

Whatever you now find...

Brian Eno, from a 1995 diary entry:

Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit – all these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.

It’s the sound of failure: so much of modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart. The distorted guitar is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it. The excitement of grainy film, of bleached-out black and white, is the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.

Wish I had seen this before I wrote my “Resistance in the Arts” essay. But I think if I had read a lot more Eno I probably wouldn’t have felt the need to write the essay at all.

December 18, 2023

Pope Francis Allows Priests to Bless Same-Sex Couples – T...

Pope Francis Allows Priests to Bless Same-Sex Couples – The New York Times:

But the new rule made clear that a blessing of a same-sex couple was not the same as a marriage sacrament, a formal ceremonial rite. It also stressed that it was not blessing the relationship, and that, to avoid confusion, blessings should not be imparted during or connected to the ceremony of a civil or same-sex union, or when there are “any clothing, gestures or words that are proper to a wedding.”

What does it mean to bless a couple without blessing that couple’s relationship? Millions of words will be expended in the coming months to try to explain this, but I can guarantee that none of them will make sense. The Pope has put his church in a completely untenable, incoherent, radically unstable position. From here it will have to go back to the traditional teaching or ahead to something wholly unprecedented. And I can’t imagine a retreat, not by this Pope.

Francis has not spoken ex cathedra here — this is not like, for instance, Munificentissimus Deus. But it’s a big thing, and if the incoherence is rectified by further acceptance of same-sex unions, then some really fancy theological dancing will have to be performed to avoid having to admit that the historic dogma on sex and marriage was simply wrong. And if a future Pope walks this back, then a similarly complicated dance will have to be done to reconcile the repudiation of Francis’s teaching with the dogma that the Pope is guided and directed by the Holy Spirit even when making ordinary — not ex cathedra — arguments and policies. It’s hard to see how historic Catholic teaching on marriage and historic Catholic teaching on papal authority can emerge unscathed from this.

Is Francis now the most consequential pope in the history of Roman Catholicism? I am inclined to say Yes.

cost-benefit

Carolyn Dever, writing about the ransomeware attack on the British Library:

We’re past the days of card catalogs, alas: the modern library has long since converted to digital recordkeeping. What this means is that readers request books electronically, and the institution charts those books’ locations electronically, too. If I wanted to see what I had been working on last summer or a decade ago, I could look up my own user record to confirm. Well, I can’t do this right now, but researchers have taken this capacity for granted for a long time. If librarians wanted to see who’d laid hands on a certain volume of Michael Field’s diary, or on the manuscripts or earliest published work of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Shelley, Keats, the Brontës, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, and so many more writers familiar today and others languishing, awaiting rediscovery, presumably they could, with a simple request within a digital file. Most importantly, if I wanted to request to see a specific book, I could look it up electronically, and then ask the librarians to find the physical copy.

Until Halloween, 2023, that is.

How ironic that the most quaintly analog form of research possible, using physical books in a physical library, has been devastated by the hijacking of a digital system. I am experiencing this irony as especially bitter this morning, having arrived at desk 1086 with my list of tasks, hoping against hope that the crisis had resolved. It hadn’t. I hope it will someday soon.

The books and manuscripts are there, the staff are there, the scholars are there — but the research can’t be done, because without the digital cataloging system there’s no way to access the materials.

During the Nineties (mainly), when libraries were gradually converting their systems from analog to digital, when you could use either system — though there were always warnings that not everything had been entered into the computer databases. I had very mixed feelings about all this. In the mid-Nineties I was regularly using telnet to scan the holdings of libraries around the world, and that seemed miraculous to me. (In those years I led several summer study programs that were housed at St. Anne’s College, Oxford, and I could find out in advance which of the books I needed were available at St. Anne’s, at the other Oxford colleges, and at the Bodleian — though access to the Bodleian was hard for outsiders to get in those days.) On the other hand, I loved looking through card catalogs for the same reason I loved browsing the stacks: serendipity. I embraced the end of the card-catalog system, but with regrets.

In every library I regularly used, for some years after the system had gone fully digital, the cabinets holding the cards stayed around. There had always been, sitting on those cabinets, pencils and sheets of paper on which you could write the call numbers you needed, but those had been taken away — oddly, because you could use them in exactly the same way you did before to find older books. But we were all being nudged towards the computer terminals. Eventually the cabinets were taken away and replaced by comfy chairs. The smaller cabinets are now widely available on eBay.

December 15, 2023

words, words, words

Many of our arguments are fruitless because we don’t know the meaning of the words we use. And we don’t know the meaning of the words we use because meaning is not a property of language that our culture thinks important. In common usage, especially on social media, words are passwords, shibboleths — they are not employed to convey any substantive meaning but to mark identity. You use the words that people you want to associate yourself with use; it doesn’t go any further than that. If they call Israel an example of “colonialism,” then you will too, regardless of the appropriateness of the word.

For this reason, my frequent inquiries into the words and phrases people rely on as identity markers are probably the most useless things I write. But I keep writing them in the hope that at least a few readers will realize that they don’t have to accept the language that is most widely used, that they are free to use other words, or to ask other people what, specifically, they mean by the words they rely on.

In How to Think I conducted such an inquiry into the phrase “think for yourself.”

A while back on this blog, I tried to understand what people mean when they denounce “critical theory” — and “critical race theory” as well.

In a recent essay in Comment I ask whether people know what they mean when they use the word “gender.”

And today I’ve posted a short essay at the Hog Blog in which I suggest that the term “self-censorship” is incoherent and inappropriate.

Those are just a few examples; I could cite a hundred. I keep doing this kind of thing, fruitless as it sometimes feels, because if even a few people disrupt the thoughtless recycling of automatic phrases, some of our shouting contests could become actual arguments. And that would be a win.

December 13, 2023

multiple social diseases

18 Warning Signs of a Deadly New Lifestyle – by Ted Gioia: — but they’re not all symptoms of the same disorder — or anyway not in the same way.

“Anthropophobia — the fear of other people — is on the rise” is the chief theme, and “Time spent alone is rising for all demographic groups” and “People no longer build friendships” are related phenomena. But others may reflect quite different motives and concerns.

For instance: “After centuries of intense urbanism, more people now want to live in the country — away from bustling cities, suburbs, or even small towns.” This could be a symptom of anthropohobia, but it also could arise from a desire to reconnect with the natural world, a world our social order hopes to make irrelevant. (“Why move to the country when you can watch this YouTube video of snow falling in a wilderness cabin? — and without ads for a nominal monthly fee!”) So a desire to move to the country might be related to a settled and well-earned suspicion of Technopoly’s ability to meet all our needs.

(I know some folks who left big cities for small towns or the countryside during Covid and now couldn’t be brought back at gunpoint — and it’s not because they dislike people. They meet fewer people in the course of any given day, but the ones they know they know better, more meaningfully, than they knew the people they saw on a daily basis in the city.)

And: “Even humanities professors don’t want to deal with human beings.” The essay that Ted links to discusses, among other things, the difficulty that editors of academic journals have in getting peer reviewers for the submissions they receive. Until fairly recently, here’s how that worked: A journal editor wrote to me and asked me to review a manuscript. If I said yes, he sent me the manuscript and I wrote back with my thoughts. But now? An editor writes to me, tells me that he or she has taken the liberty of assigning me a username and a password at a website that manages a “reviewer database,” and at which I may fill out various forms and click various checkboxes on my way to providing a review that meets certain pre-specified criteria.

To that I say: Oh hell no. And my refusal is the opposite of not wanting “to deal with human beings”; it’s my declining to accept a transaction from which the humanity has been surgically removed by robots.

(Also: Why do editors have recourse to such semi-automated systems? Because they get so many submissions. Why do they get so many submissions? Because publish-or-perish is still the core principle of academic employment, and in an ever-shrinking academic job market humanities professors are cranking out scholarly articles at an unprecedented pace to try to make themselves viable candidates for the tiny handful of jobs still available. The real problem lies far, far upstream of my refusal to become another entry in someone’s database.)

So the various examples that Ted gives of this “deadly new lifestyle” point in varying and in some cases opposite directions. Some of these developments show people succumbing to Technopoly; others involve resistance to Technopoly. And that’s a big difference.

December 11, 2023

repair as scapegoat

Superficially, litter and the rusting carcasses of salvaged cars are both an affront to the eye. But while litter exemplifies that lack of stewardship that is the ethical core of a throwaway society, the visible presence of old cars represents quite the opposite. Yet these are easily conflated under the environmentalist aesthetic, and the result has been to impart a heightened moral status to Americans’ prejudice against the old, now dignified as an expression of civic responsibility.

Repair stigmatized as an affront to aesthetic sensibilities. Who makes bank from that?

Later in the essay, Matt writes:

Among the sacrifices demanded by the new gods may be your ten year old car that gets 35 MPG, requires zero new manufacturing (with its associated environmental costs), and may be good for another ten years. As Rene Girard points out, ritual violence is usually directed against a scapegoat who is in fact innocent, onto whom the sins of the community are transferred. In our pagan society of progress, it seems anything old and serviceable can serve this role.

Yep. Just the other day, responding to another post by Matt, I said that I want to keep my own 10-year-old car for another ten years. We’ll see whether I can hold out.

art for humanity’s sake

Criticism of this kind is a misuse of learning to muddle discussion for the sake of scoring points rather than to clarify it for a curious public. There is plenty of intelligent and reasonable criticism of Wilson’s work to be had from people who know the poems well — the Bryn Mawr Classical Review was positive but not uncritical, and I myself think her choices at Odyssey 15.365 were the wrong ones — and there is no need to give credence to people who consider their own desire for attention an adequate substitute for the knowledge and consideration that must attend real critical judgment.

This is well said. To almost everyone writing about art today I want to say: Dragging every scholar, every critic, every translator, every artist, every artwork before the bar of your political tribunal might, just conceivably, not be the only or even the best thing you can do when confronted by a work of art.

I don’t think we’ve ever needed genuine works of art — imaginative creations that press us to see the world in larger or at least different ways than our standard everyday media-navigation categories allow — more than we do now. But our current resources are few, because of the ways the major art-related organizations have lost any discernible sense of purpose. They are merely reactive to social-media pressure. Examples:

This essay on the publishing world; And this essay on the publishing world, written from a very different perspective; This very long but very helpful video on what’s wrong with the movie industry; This deeply reflective essay on the depressing world of art criticism and the contemporary museum.In light of these developments I’ve come to believe that the most important thing I can do here on this blog is to write about art as art — which is not to say that art lacks political purposes and implications. Often it is powerfully political. But no artwork worthy of our attention approaches politics the way that journalists and people on X do, as a matter of checking the right boxes to avoid exclusion from the Inner Ring. One thing good art always does is to remind us that our experience is dramatically larger than our quotidian political categories suggest. We are unfinalizable; we sprawl. The failure to recognize that is a terrible disease of the intellect.

I am finished — not altogether, but largely, I think — with political and cultural disputation. I want to write about works of art that transcend the box-checking, that thwart easy dismissals, that shake us up. And if the current art scene doesn’t offer any of that, then I can always continue to break bread with the dead.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers