Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 247

July 21, 2018

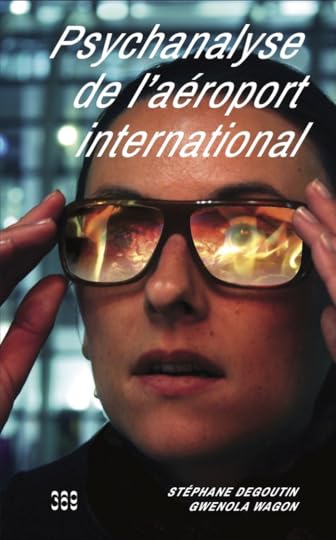

our airport future

Two quotes from this interview with Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon. One:

SD: The airport is where different promises of the modern world are concentrated: the promise of moving freely around the globe, the promise of unlimited shopping, the promise of a completely rational organisation and the promise of a perfect surveillance. It embodies the desire of mastering the world. Yet, it is also the place where these promises meet their limits and their contradictions.

And two:

GW: The airport is an archetypal place, in terms of both space and behaviour. In the book, we have a chapter about what we call “Cultural LCD”, which can be defined as the Least Common Denominator of world cultures. A universal code that would be as neutral as possible, a standardized interface that allows different individuals or cultural groups to communicate with each other. However, the airport model is expanding further and further and contaminating railway stations, institutions, monuments, stadiums, concert halls, museums, international hotels, malls and urban duty-free shops, restaurants, museums, schools, universities, offices, motorway service areas, etc.

This is fascinating and … horrifying.

For the Love of Mars

Once we come of cultural age into a mature, considered love for Mars, and see what happens when we act on that love, our crises and challenges on Earth can be recast, as can our menu of choices in meeting them. Rather than panic and rancor, scripted according to the prevailing social and political battle lines that have replaced the grand frontier, we will be more apt to find confidence, courage, and creativity. And rather than applying these virtues to the virtual world that draws us deeper into antihuman utopias, we’ll apply them to the metal-and-plastic, flesh-and-blood, brick-and-mortal world that forms an essential bridge between analog and digital life. It shouldn’t be a surprise that this approach will also happen to fit in logically with the reality that our younger kids now experience.

A really fascinating essay by James Poulos. The core of James’s argument, and it’s a point that deserves extended contemplation, goes something like this: We think all the time about the technologies we use or might use, but we don’t think at all about the object of our technological explorations, the sovereign end (telos) of our ingenuity. The pursuit of Mars, James thinks, can be a kind of collective focal practice (to borrow a term from Albert Borgmann) that brings order and purpose to our technological strivings.

Whether this proposal can actual work will depend, I think, on whether it has the follow-on effects that James believes it will — follow-on effects that make life on Earth better, as described in the paragraph quoted above. I’m no so sure. But what a wonderfully imaginative and provocative essay.

July 20, 2018

the church in Imminent America

So just as an intellectual exercise, let’s make a bold prophecy for the 2040s or so. Imagine a near future US where a state’s population corresponds to its degree of urbanization, and thus to its relative secularity. Imagine the most thriving regions of church loyalty being concentrated strongly in The Rest, those 34 states containing thirty percent of the nation’s people, especially in the Midwest and the Upper South. The metroplexes, in contrast, are very difficult territory indeed for believers of any kind, a kind of malarial swamp of faith. A situation much like contemporary Europe, in fact.

Catholics, of course, face special issues in this Imminent America, and all depends on how far they can retain the loyalty of that very large Latino presence.

Hmm, planning a church for the hyper-urban future ….

These are enormously complex demographic issues that every thoughtful Christian should be considering. I wonder whether the existing national structure of Christian denominations can survive a future in which the 16 states of Metroplex America and the 34 states of The Rest experience greater and greater cultural divergence. It might be that the forms of faithful Christian living in the one context look very different than those in the other, even when there is substantial theological agreement.

I’m inclined to think that every church that wants to live into the urban future should read the work of Mark Gornik, especially his book on African Christianity in New York City — an amazing tale. Very few people would believe just how many Christians there are in New York, especially (but not only) from the African diaspora. There are wonderfully thriving Christian communities that fly wholly under the radar of our cultural attention, and will probably never be noticed by the culture at large. But Christians who want to bear witness into the future ought to notice them.

And City Seminary, of which Mark was a founder, should be observed also, especially as a model for how to train bivocational Christian leaders for a world in which full-time ministry will, in all likelihood, be rarer and rarer.

the point of the sword

What my father seeks is not a return to times that were worse for women and people of color but progress toward a society in which everyone can get by, including his white, college-educated son who graduated into the Great Recession and for 10 years sold his own plasma for gas money. After being laid off during that recession in 2008, my dad had to cash in his retirement to make ends meet while looking for another job. He has labored nearly every day of his life and has no savings beyond Social Security.

Yes, my father is angry at someone. But it is not his co-worker Gem, a Filipino immigrant with whom he has split a room to pocket some of the per diem from their employer, or Francisco, a Hispanic crew member with whom he recently built a Wendy’s north of Memphis. His anger, rather, is directed at bosses who exploit labor and governments that punish the working poor — two sides of a capitalist democracy that bleeds people like him dry.

“Corporations,” Dad said. “That’s it. That’s the point of the sword that’s killing us.”

July 19, 2018

July 17, 2018

the moral ideal

When the guide of conduct is a moral ideal we are never suffered to escape from perfection. Constantly, indeed on all occasions, the society is called upon to seek virtue as the crow flies. It may even be said that the moral life, in this form, demands a hyperoptic moral vision and encourages intense moral emulation among those who enjoy it…. And the unhappy society, with an ear for every call, certain always about what it ought to think (though it will never for long be the same thing), in action shies and plunges like a distracted animal….

Too often the excessive pursuit of one ideal leads to the exclusion of others, perhaps all others; in our eagerness to realize justice we come to forget charity, and a passion for righteousness has made many a man hard and merciless. There is indeed no ideal the pursuit of which will not lead to disillusion; chagrin waits at the end for all who take this path. Every admirable ideal has its opposite, no less admirable. Liberty or order, justice or charity, spontaneity or deliberateness, principle or circumstance, self or others, these are the kinds of dilemma with which this form of the moral life is always confronting us, making a see double by directing our attention always to abstract extremes, none of which is wholly desirable.

— Michael Oakeshott, “The Tower of Babel”

truth and lies

I’ve always had great admiration for those who, in the chaos that generally characterises the present, sensed from the start the enormous dangers of Nazi-fascism and courageously denounced it. But do we still have the capacity to be as far-seeing? Do the conditions exist today for the long view?

Sometimes I think I understand why we women increasingly read novels. Novels, when they work, use lies to tell the truth. The information marketplace, battling for an audience, tends, more and more, to transform intolerable truths into novelistic, riveting, enjoyable lies.

July 16, 2018

unforeseen consequences

Another follow-up on my baseball post. I’m getting two kinds of feedback: (a) you’re a moron, sabermetrics is awesome, and (b) you’re absolutely right, sabermetrics is terrible.

Let me emphasize a point that I think is perfectly clear in the piece itself: I love sabermetrics. I started reading Bill James in, I think, 1981; I have written fan letters to him, Rob Neyer, and (later) Voros McCracken (for heaven’s sake); when James came up with the earliest serious attempt to evaluate fielding, Range Factor, I spent countless hours that should have been devoted to my doctoral dissertation trying to improve it — using (by the way) pencil, paper, and a TI SR-50 calculator. I was pontificating about the uselessness of assigning wins and losses to pitchers when Brian Kenny was scarcely a gleam in his father’s eye. If in those days one of those sabermetricians had offered me a job as an assistant, I would’ve dropped out of grad school in an instant.

So in many ways it has been enormously gratifying to me to see the undoubted insights and revelations of serious statistical study make their way into the practices of professional baseball. But such changes have had some unforeseen consequences, and my post was largely about those.

This, by the way, is what those of us with a conservative disposition are supposed to do: When everyone else is running to embrace some new exciting opportunity, we warn that there will be unforeseen consequences; and then, when we have been (as we always are) ignored, we help conduct the postmortem and point out what those consequences actually were. (I was, needless to say, not allowing my conservative side to have a voice when I was so absorbed in sabermetrics — but that was because I never for one second imagined that people running professional baseball organizations would pay attention.)

Now, we might actually like the new opportunity. We might think that on balance it’s worthy to be pursued. So we don’t necessarily stand athwart history shouting Stop. We might instead stand judiciously to the side and quietly ask Do you know what you’re getting into? Because there will be trade-offs. There are always trade-offs.

July 15, 2018

converging on rational standards: not always bad!

This is a follow-up to my just-posted essay on my unchosen-but-apparently inexorable declining interest in baseball. My chief point there is that baseball has increasingly converged on a set of Best Practices but that convergence has made baseball less interesting to watch. (And my secondary point is that this is ironic because the practices now being converged upon are the ones I used to cheerlead for when they were far less common.)

That’s the way it has turned out in baseball, but it doesn’t always turn out that way. Take basketball, for instance, and more particularly all the controversy in the last NBA season about Lonzo Ball’s peculiar jump shot: I can remember a time when Lonzo’s technique wouldn’t have been unusual at all. When I first started watching basketball, in the 1970s, there were some weird-looking shots, let me tell you. The most notorious of these was the Jamaal Wilkes slingshot, but Jamaal had a lot of competition. Gradually, though, coaches at all levels came to understood that certain ways of holding and releasing the ball simply made for far greater and more consistent accuracy than others, and players started getting the relevant guidance even in their first organized games. So we have seen a very widespread convergence on the Best Practices of Shooting a Basketball.

And the result has been great for the game. It wasn’t just implementing the three-point line that created the free-flowing, open, spread-the-floor offense that the Golden State Warriors delight us with; it was the rise of a generation of players who have the shooting technique to take advantage of that line. In at least this one situation in this one sport, standardization of technique has led to increased creativity and possibility; in baseball, I fear, just the opposite has happened.

(I am now thinking that I ought to write a short book or long essay called “Rationalism in Sports” to serve as a counterpart to Oakeshott’s “Rationalism in Politics.”)

July 14, 2018

suffering and not triumph

Are we then to deduce that we should forget God, lay down our tools, and serve men in the Church – as though there were no Gospel? No, the right conclusion is that, remembering God, we should use our tools, proclaim the Gospel, and submit to the Church, because it is conformed to the kingdom of God. We must not, because we are fully aware of the internal opposition between the Gospel and the Church, hold ourselves aloof from the Church or break up its solidarity; but rather, participating in its responsibility, and sharing the guilt of its inevitable failure, we should accept it and cling to it. — I say the truth in Christ, I lie not, my conscience bearing witness with me in the Holy Ghost, that I have great sorrow and unceasing pain in my heart. This is the attitude to the Church engendered by the Gospel. He who hears the gospel and proclaims it does not observe the Church from outside. He neither misunderstands it and rejects it, nor understands it and – sympathizes with it. He belongs personally within the Church. But he knows also that the Church means suffering and not triumph.

— Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers