Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 238

October 27, 2018

Issa Megaron

October 26, 2018

Breaking Bread with the Dead

I tweeted this news a while back, but am only now finding time to write about it at greater length: My next book will be called Breaking Bread with the Dead: The Case for Temporal Bandwidth, and will be published by Penguin Press (probably in 2020). You can find a kind of preview of the book by reading this essay I wrote for the Guardian.

I think of this book as the conclusion of my Pedagogical Trilogy, the first volume of which was The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction and the second of which was How to Think. Finding delight in reading, learning to think well in opposition to all the social forces that impede thinking, drawing on the wonderfully diverse intellectual resources of the past — these three themes encapsulate much of what I have tried to teach my students for the past thirty-five years.

I have found over those years that when I’m working on a book I don’t do well when I have only that book to work on. Some days I just can’t make progress — most often because I’ve been thinking too much about the issues involved — and I need to get away from the project. I can achieve that best when I have a very different, but also intellectually demanding, project that I can turn to for a brief time. (This is why I sometimes have two books appear within a relatively short period of time: I had two come out in 2008, two in 2011, two in 2013, and two within nine months in 2017 and 2018.)

The second project that I’ll occasionally turn to while my primary attention goes to Breaking Bread with the Dead is my long-meditated treatise on what I have sometimes called Anthropocene Theology — though the working title is now The Far Invisible: An Anthropology for Failed Gods. I have about 80,000 words of that book written, though many of the current words will be replaced by others and there is still a great deal yet to write. But here I want to emphasize that I have not abandoned that project; indeed I am more committed to it than ever. It’s just going to take longer than I had originally thought.

One interesting thing about this particular pairing of projects is that one is very much oriented to the past and the other very much occupied by the future. I’m excited to see how each influences the other.

Writing well ≠ dumbing down

This by Ian Bogost is exactly right:

I suspect that what scholars and other experts really mean when they express worry about “dumbing down” is that they don’t want to be bothered to do the work of reframing their work for audiences not already primed to grasp it. It’s hard to do and even harder to do well. That’s a fine position; after all, it’s the full-time job of journalists and non-fiction writers to translate ideas for the general public from their specialized origins. Not every scholar can, or should, try to do this work themselves (although, to do so exercises the generosity that comes from service.)

But to assume that even to ponder sharing the results of scholarship amounts to dumbing down, by default, is a new low in this term for new lows. Posturing as if it’s a problem with the audience, rather than with the expert who refuses to address that audience, is perverse.

I have done a great deal of writing for my scholarly peers and for broader audiences, and there is no doubt that the latter is more challenging. The great difficulty is to make what you have to say as simple as possible but no simpler — which means that you often have to work very hard to express certain ideas in ways that are accessible but non-reductive.

And — I hesitate to say this, but here goes — I think you usually have to know your stuff better to write well for a general audience. If you’re writing for your scholarly peers, there are certain critical buzzwords, voguish phrases, and terms of art that you can use to gesture in the direction of a concept, trusting that people who have used those terms themselves will pick up on what you’re saying. But you don’t even have to have a very clear understanding of the concepts in order to deploy the terms — you just have to have a sense of the kind of sentence in which they belong. By contrast, when you’re writing for a general audience who does not know the language of your guild, you have to understand those concepts well enough to translate them into a more accessible idiom.

Many academics who haven’t tried to write for broader audiences fail to understand the challenges. But I bet at least some of them have a pretty shrewd intuition of how hard it is — which gives them a good reason to sneer at it.

October 23, 2018

angel

October 22, 2018

“drive out the wicked person”

Michael Ramsey, from The Anglican Spirit:

While holiness is both a fact and a potentiality, it is impossible to enforce the holiness of the church by rejecting people who do not conform to certain moral canons. That has been tried often in the history of the church, most notably by the early Puritans. When one says that the church is meant to be holy and therefore we will exclude those who are not holy, the inevitable happens. You can turn out the fornicators, the murderers, and those who apostasize in times of persecution; you can turn out sinners of every kind, but you cannot turn out the sin of pride. This sin, the most deadly of all, is always present but not always easily identifiable. So if you are going to purge the church of sinners, you will need to purge it of the sin of pride and turn everybody out. As Anglicans, we believe these attempts to purify the church by certain ethical criteria cause it to lose the reality of what it means to be dedicated to the holiness of God.

St. Paul, from his first letter to the church at Corinth:

I wrote to you in my letter not to associate with sexually immoral persons — not at all meaning the immoral of this world, or the greedy and robbers, or idolaters, since you would then need to go out of the world. But now I am writing to you not to associate with anyone who bears the name of brother or sister who is sexually immoral or greedy, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or robber. Do not even eat with such a one. For what have I to do with judging those outside? Is it not those who are inside that you are to judge? God will judge those outside. “Drive out the wicked person from among you.”

So Ramsey is simply wrong, isn’t he? For when he says “we believe these attempts to purify the church by certain ethical criteria cause it to lose the reality of what it means to be dedicated to the holiness of God,” he certainly seems to be flatly disagreeing with St. Paul. And surely this is not acceptable — even for Anglicans.

Whether we leave it at that will depend, I suspect, on whether we think Paul’s list of those who must be driven from among us (“sexually immoral or greedy … an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or robber”) is exhaustive or illustrative. If the former, then Ramsey is absolutely and totally wrong, full stop. For Paul does not say that we are to drive the prideful from among us — nor, for that matter, the violent, the habitually dishonest, and so on.

But if Paul’s list is illustrative, and his point is that ecclesial communities should shun what the old prayer book calls the “open and notorious evil liver,” then Ramsey is still wrong, I believe — but despite being wrong he calls us to reflect on something important: that is is very easy to be highly selective, and selective in a fundamentally unprincipled way, about which sinners we shun. For in an environment where declining church attendance makes pastors disinclined to shun anyone, the low-hanging fruit is to drive out from among you those (a) whose sins are really obvious and (b) who are already unpopular with your regular attenders, your most generous givers.

It’s easy enough to say that when pastors discipline big donors — which no doubt sends said donors headed straight for the door — their people will really respect them for it. Unfortunately that isn’t true. People will just think those pastors are stupid. And few pastors actually are that stupid.

I really feel for pastors in this situation. I don’t know what they can do that isn’t either disobedient, self-destructive, or inconsistent (inconsistent at best, hypocritical at worst). The state of American Christianity today, with its inherent consumerism, means that any pastors who try to impose church discipline impartially will find themselves with an empty church or, more likely, find themselves out of a job. But, as Lyle Lovett once said in a rather different context, we have to try. What would we be if we didn’t try?

So the question is: What would a truly Christian, truly biblical, model of church discipline look like?

back to the Mac

I’ve spent a lot of time in the past year trying to leave the Mac behind and move full-time to iOS. I’ve done this in large part because the many and various problems I’ve had with the last several versions of Mac OS have convinced me that it’s not getting Apple’s best attention, that iOS is likely to be the more reliable platform in the future, and that I’d do well to start adapting my patterns and habits accordingly.

Of course, iOS isn’t the only option, and in fact, a couple of years ago I tried to move to Linux. But not only am I pretty heavily invested in the Apple ecosystem, my family members are also, and on Linux I really missed the convenience of sharing apps, answering phone calls on my computer, Messages, FaceTime, etc. So I was gradually sucked back into Cupertino’s orbit.

So, I tried Linux, and then I tried iOS. Now I’m back to the Mac. Why? There are many reasons, but here are the biggies:

As many, many people have pointed out, text selection has never worked consistently in iOS and has not improved even a little bit over the past few years. And text selection is something I do a lot of.

I have often sung the praises of pandoc — it is essential to my work — and there is simply no equivalent of pandoc on iOS. You can do most of the things pandoc does there, but with more steps, more effort, and less consistent results.

Mojave has fixed all the problems I had with the previous two or three versions (I’m especially pleased that wifi and Bluetooth both work flawlessly now).

On iOS, TextExpander works in some apps; on the Mac, it works everywhere. This is huge for me. I have developed a very large library of TextExpander snippets over the years, and when I’m writing in an app and they don’t work I get weird glitches in my neural software.

And I don’t enjoy getting weird glitches in my neural software. So I’m back on a Mac.

October 21, 2018

American Airlines rejects my reality and substitutes its own

Yes, this is a kind of rant, but it’s also something more: an account of how transcendentally weird air travel can be these days.

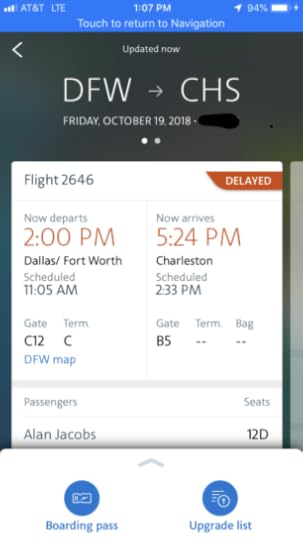

A few days ago my wife and I were scheduled to fly on American Airlines from Dallas to Charleston. But our flight, which was to leave just after 11am, was delayed and delayed and delayed, and when we were told that our plan couldn’t be repaired and a new plane had to be found, Teri and I decided to see if we could be rebooked on another flight, the AA rep at the gate said that neither she nor anyone else at the airport could help us (!?) — we would have to call AA’s toll-free number. So, around 1pm, we did, and here’s what the customer service rep told us: “I can’t help you because your flight is already in the air.” I said, “I’m sitting here at the gate with maybe a hundred other people waiting for a new plane.” “I’m sorry, your flight is already in the air. It departed at 12:53pm.” And then she hung up. That’s when I took this screenshot of my just-updated AA app:

At this point we were at a loss, but as more time went by and there was no sign of a plane, we decided to give up and go home. Then each of us got busy seeking a refund (Teri’s return flight was different than mine, and her fare was purchased separately.)

Today I got an email from AA reading thus: “In fact flight AA2646 was only delay for 14 minutes before taking off on October 19, 2018. I would not be able to offer a refund for the ticket or waive the change fee.” Wait, 14 minutes??? Even the person who insisted that the flight was already in the air at 1pm thought it had just taken off, nearly two hours late.

Apparently no one in customer service at American Airlines has even remotely accurate data about the status of their flights. Moreover, that data seems to be in constant flux.

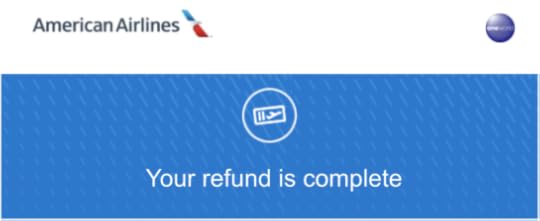

Well, maybe someone does, because about an hour before I got that email here’s what Teri got:

So, though we were booked on the same flight, hers was either cancelled or delayed so long that she got a refund, while mine was only 14 minutes late. Proof of the multiverse hypothesis, I guess?

But I’ll tell you this: I ain’t flying American Airlines again.

WE REACH FOR A BOOK

October 18, 2018

ancient feelings

Why doesn’t ancient fiction talk about feelings? “I’d often wondered,” says Julie Sedivy, “when reading older texts: Weren’t people back then interested in what characters thought and felt?” Let me put this as politely as I can: What the hell are you talking about?

If you read the Iliad you’d know how Achilles felt when Agamemnon took his “prize,” or how he felt when his beloved friend Patroclus was killed. If you read the Odyssey you’d know how Odysseus felt when his men were being eaten by Polyphemus, and how he felt when he fell, at last, into the arms of his beloved wife Penelope. If you read the Oresteia you’d know how Orestes felt when faced with the task of killing his mother. If you read Antigone you’d know how the title character felt when told she could not bury her brother. If you read the Aeneid you’d know how Aeneas felt when he saw his fellow Trojans painted on the walls of a palace in Carthage — sunt lacrimae rerum, there are tears for things, possibly the most famous line in ancient literature — and how Dido felt when she learned that Aeneas would leave her. If you read Beowulf you’d know how Beowulf felt when, after slaying a dragon, he lay dying, abandoned by all but one companion. If you read the Divine Comedy you’d know how Dante the pilgrim felt about everything, from getting lost in a selva oscura to disappointing his guide Vergil to meeting his old friend Casella the musician to being reunited with Beatrice.

I’m old as dirt and have seen people take many ridiculous positions in my time, but none more ridiculous than this.

October 17, 2018

Hastings House Book of Hours

The lovely Hastings House Book of Hours, from this great I Love Typography post, which has other cool images as well.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers