Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 214

October 2, 2019

This is and always will be one of my favorite album covers

This is and always will be one of my favorite album covers

This is and always will be one of my favorite album covers

September 28, 2019

excerpts from my Sent folder: criticism

Well, first of all, it’s important to remember that a lot of criticism of your work really doesn’t have anything to do with your work or you. Your words may provide for some a launch pad to say something they want to say anyhow — these are the people who come to lectures and during the Q&A say “This is really more of a comment than a question” — and for others it’s an opportunity to strut and fret their hour upon the social-media stage, or to preen and flex in the mirror that your text provides them. It’s not about you, it’s about them, and in any case they’ll be on to something else that displeases them in an hour or two. So who cares?

But if someone takes the trouble to pay attention to what you’ve written, to grasp your argument and to show where they think it goes wrong, or to bring in evidence that you’ve neglected (or didn’t know about) — that kind of thing is above rubies. But it’s very very rare.

September 27, 2019

alternative headline

Richest University on the Planet Still Getting Richer While Other Universities Are Threatened with Closure, But Who Cares about Them?

Richest University on the Planet Still Getting Richer While Other Universities Are Threatened with Closure, But Who Cares about Them?

September 25, 2019

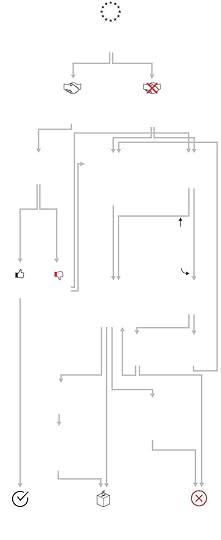

textless Brexit flowchart

look at what came in the mail

September 24, 2019

Monk’s specs

If you’re ever tempted to think you’re cool, just remember that Theolonious Sphere Monk was wearing those specs in 1947.

If you’re ever tempted to think you’re cool, just remember that Theolonious Sphere Monk was wearing those specs in 1947.

John Mitchell

Tide offensive lineman Jimmy Rosser recalled that before [Wilbur] Jackson enrolled and Mitchell was recruited, Bryant “told us that he was going to get the best athletes available to play for us and that included black players. He then proceeded to tell us that if any of you didn’t like that, then you could get the hell out of here, because that was the way it was going to be. None of the players left the meeting.”

Still, Mitchell knew what world he was entering because of the world he was raised in. He attended segregated schools in Mobile, and his Williamson High School team was barred from playing at Ladd Stadium, even though it was across the street. He only saw black players there when he sold sodas in the stands at the Senior Bowl, he recalled.

Having lived that life, what greeted him on campus was an adjustment: He had never had white teachers before, nor white classmates, and he was the only black student in each of his classes in Tuscaloosa. The black enrollment at the time — about 3% of 15,000 students — meant this for him: “You wouldn’t see an African American student for three or four days.”

I remember very well what I felt when John Mitchell — the first black football player at the University of Alabama, the first black captain of the team (elected by his teammates), the first black assistant coach (immediately after his graduation at age 20) — and other black players arrived on the scene. I was about twelve. I felt that a Dark Age had ended. I was sure that we in Alabama would soon put racism behind us. Finally, all that would be over.

September 22, 2019

I’m going to say something I never ever believed that...

I’m going to say something I never ever believed that I would say in earnest: I think Arsenal should sack Emery and replace him with Mourinho. It would be only a transitional move, because Mou never lasts more than three years without disaster, but if there is one thing he can do it’s organize a defense. Emery patently cannot do that. At all. And if Arsenal are going to make a change they need to do it soon, before the season slips away. Or slips away any further than it already has.

P.S. This assumes that Mourinho would take the job. I think he would, if only because the club is in London.

P.P.S. And no, the result against Villa doesn’t change my mind. The lads fought back bravely, but they were digging themselves out of a hole their manager’s tactical ineptitude and inexplicable personnel decisions put them in.

intellectuals and influencers

Both the public intellectual and the public influencer play an instrumental role in shaping cultural ideals and tying them to the individual’s sense of self. When the public intellectual was ascendant, cultural ideals revolved around the public good. Today, they revolve around the consumer good. The idea that the self emerges from the construction of a set of values and beliefs has faded. What the public influencer understands more sharply than most is that the path of self-definition now winds through the aisles of a cultural supermarket. We shop for our identity as we shop for our toothpaste, choosing from a wide selection of readymade products. The influencer displays the wares and links us to the purchase, always with the understanding that returns and exchanges will be easy and free.

— This from Nick Carr is short and sharp and smart. Please read the whole thing, especially the last paragraph, which ends on a zinger. (I feel zinged, anyway.) Nick’s post is a useful contribution to the understanding of what I’ve been calling metaphysical capitalism, which is the transformation of the commodified self into a religion.

Also, this gives me the opportunity to answer a question some people have been asking me: What exactly is the narrative promoted by the reporting of New York Times that I dislike so much? The short answer is: metaphysical capitalism. For the reporters on the Times, those who tell me that “I am my own” are on the side of the angels, while those who cast doubt on that proposition are to be cast into outer darkness where there is wailing and gnashing of teeth. (Thus genuinely Left movements get only marginally better treatment in the Times than religious conservatives.) That is the primary means by which Times reporters evaluate everything from political candidates to religious organizations to movies and books. There is not even the slightest attempt in those pages to be fair to people who question self-ownership, for what fellowship has light with darkness?

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers