Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 189

November 6, 2020

back to the urbs

Many years ago I wrote a post about living in a suburb — Wheaton, Illinois — but having a life that in many ways felt more like what city life is supposed to be:

For people like me Wheaton doesn’t feel like a suburb at all, and many aspects of my life sound kinda urban. My family and I live in a small house – with one bathroom, for heaven’s sake – and have a single four-cylinder car. I walk to work most days, frequently taking a detour to Starbucks on the way. From work I often walk to Wheaton’s downtown to meet people for lunch, or, at the end of the day, to meet my wife and son for dinner. Drug stores and a small grocery store are equally close; I even walk to my dentist. I also like being just a short stroll from the Metra line that takes me into Chicago, just as Chicago residents like living just a short stroll from the El. And I know many other people who live in much the same way.

The point of my post is that the common opposition between “city life” and “suburban life” obscures many vital distinctions and gradations.

I don’t live in a suburb any more, I live in a city. But because the city I live in — Waco, Texas — has 125,000 people rather than millions, it’s not the kind of place that people refer to as urban when they talk about “America’s urban-rural divide.” For example, here is a piece by Eric Levitz that uses the binary opposition in the conventional way, or what seems to me to be the conventional way. I can’t be certain, but I strongly suspect that Levitz thinks that people who live in cities the size of the one I live in — especially if those cities are south of the Mason-Dixon Line — are “rural.” But they aren’t. Even if we don’t think or vote like New Yorkers.

When people talk about “the urban-rural divide in America,” I think what they usually mean is “the divide between people who live in megacities and people who live everywhere else.”

November 5, 2020

weakness and isolation

Two random, one relatively significant and one relatively trivial, thoughts on this op-ed by Ian Marcus Corbin. The more significant one first. Corbin writes,

Most stroke patients ultimately remain able to get around, leave the house and socialize, albeit more slowly and awkwardly than before. But they often require extra time and help with things that used to be easy and fluid. Here is where they need their family, friends and acquaintances to rally around them. The worst thing for them, medically speaking, is to be isolated.

Unfortunately, studies show that stroke patients’ networks tend to contract in the wake of a stroke. Why? The causes are not perfectly clear, but we can say this: Too often in America, we are ashamed of being weak, vulnerable, dependent. We tend to hide our shame. We stay away. We isolate ourselves, rather than show our weakness.

I suppose we can say that, but is it true? My experience suggests that when people suffer their social networks contract because others don’t want to be around them. Sometimes the withdrawal arises from a lack of compassion, but more often, I think, because we find it awkward to deal with suffering: We don’t know what to do or say, and we’re afraid that we’ll do or say the wrong thing. To assume, as Corbin does, with no discernible evidence, that people self-isolate out of pride seems like a classic case of blaming the victim.

The second point is trivial but, I think, interesting. Corbin again:

The anthropologist Margaret Mead was once asked to identify the earliest material sign of human civilization. Obvious candidates would be tool production, agricultural methods, art. Her answer was this: a 15,000-year-old femur that had broken and healed. The healing process for a broken femur takes approximately six weeks, and in that time, the wounded person could not work, hunt or flee from predators. He or she would need to be cared for, carried during that time of helplessness. This kind of support, Dr. Mead pointed out, does not occur in the rest of the animal kingdom, nor was it a feature of pre-human hominids. Our way of coping with weakness, as much as our ingenious technologies and arts, is what sets us apart as a species.

Over the past few years this has become an oft-told tale, but there’s no real evidence that Mead ever said this.

November 1, 2020

I think we’re all bozos on this bus

For the last few weeks I’ve been tinkering with a draft of a post on American incompetence — on the basic inability of almost everyone in this country simply to do their jobs. That was time ill spent, because Kevin Williamson has performed the task it for me, and done it well:

It is easy to see the advantage of offering not ideology or even innovation but bare competence — competence is an increasingly rare commodity in American life. Consider the 21st century so far: the intelligence and security failures that led to 9/11, the failure to secure American military and political priorities in Afghanistan and Iraq, the subprime-mortgage boom that sparked the financial crisis of 2008–09 and the subsequent recession, business bailouts, the failures and abuses of American police departments and the riots and arson that have accompanied them, the COVID–19 epidemic, the troubles in the universities, the fecklessness and mischief of the big technology companies, the political failure to deal with serious issues from illegal immigration to environmental degradation, American frustration at the rise of China as a world power and the geopolitical resurgence of such backward countries as Turkey and Russia, the remorseless piling up of the national debt and unfunded entitlement liabilities, bankrupt and nearly bankrupt cities and public agencies — the list goes on. Americans are not wrong to question the competence of American government and American institutions, nor are they alone in doing so: The rest of the world is reevaluating longstanding presumptions of American competence, too.

And furthermore:

If things go wonky on Tuesday, if the presidential election goes unresolved and the subsequent contest is marked by political violence and civil disorder, American credibility will slide further still. In the event of an electoral crisis, we will be forced to rely on institutions that already have been tested and found wanting: Congress, many state governments, the news media, the professional political caste. And Americans will turn for information and insight … where, exactly? Twitter? Facebook? Fox News? Talk radio? The New York Times? Even the police upon whom we rely for basic physical security have shown themselves all too often unable or unwilling to perform their most basic duties.

What we need as a nation, more than anything else I can think of, is a recommitment to basic competence, and, especially, a refusal to accept ideological justifications for plain old ineptitude. Too often Americans give a free pass to bunglers and bozos who belong to their tribe. We have for decades now operated under the assumption that our material and social world will function perfectly well on its own even if we cease to attend to it. It won’t.

October 28, 2020

it’s time

I read stories like this almost every day: banned from Twitter for no good reason; banned from Facebook for no good reason; banned from Facebook supposedly by accident, but come on, we know what’s going on here.

I don’t for an instant think Bret Weinstein’s Facebook account was flagged by an algorithm: someone there wanted to silence him and hoped to get away with it. But most of the time these bans happen because the sheer scale of these platforms makes meaningful moderation impossible. Facebook and Twitter would have to hire ten times the number of moderators they currently employ to make rational judgments in these matters, and they won’t voluntarily cut into their profits. They’ll continue to rely on the algorithms and on instantaneous denials of appeals.

Here’s your semi-regular reminder: You don’t have to be there. You can quit Twitter and Facebook and never go back. You can set up social-media shop in a more humane environment, like micro.blog, or you can send emails to your friends — with photos of your cats attached! If you’re a person with a significant social-media following, you can start a newsletter; heck, you can do that if you just want to stay in touch with five of six friends. All of the big social-media platforms are way past their sell-by date. The stench of their rottenness fills the room, and the worst smells of all come from Facebook and Twitter.

In your heart you know I’m right: It’s time to go.

P.S. Of course, I’ve been singing this song for a long time. I return to it now simply because the election-as-mediated-through-social-media seems to be exacerbating the misery of millions and millions of people. I’ll try to sing a different song from now on.

October 20, 2020

rediscovery

Via Patrick Rhone, I discovered this newsletter by Mo Perry, in which she discusses the Triumph of the Scold:

Now my social media feed is full of people scolding others who have the audacity to try to salvage a shred of joy and pleasure from their lives. The lens seems largely political: as if anyone experiencing pleasure or expressing joy while Trump is president is tacitly endorsing Trump. The communally encouraged state of being is dread and misery and rage. People who eat at restaurants, people who let their kids play on playgrounds, people who walk around the lake without a mask — all condemnable, contemptible. Selfish. How dare they?

But maybe, Perry suggests, the universality of scolding is having an unanticipated consequence. She describes a recent mini-vacation with a friend:

We didn’t share a single picture or post about the trip online. Not on Instagram, not on Facebook, not on Twitter. On the one hand, it felt like a naughty indulgence — something we had to do on the DL to keep from getting in trouble. On the other, it was a revelation: This chance to rediscover privacy. To inhabit my experience without broadcasting it or framing it for public consumption.

A ray of hope, this thought. That what the scolds will achieve is to push the rest of us “to rediscover privacy.” To take photos that we share only with friends; to articulate thoughts just for friends. To leave Twitter and Facebook and Instagram to the scolds, who will then have no choice but to turn on one another.

the college experience

Ian Bogost, speaking truth to both power and powerlessness:

Without the college experience, a college education alone seems insufficient. Quietly, higher education was always quietly an excuse to justify the college lifestyle. But the pandemic has revealed that university life is far more embedded in the American idea than anyone thought. America is deeply committed to the dream of attending college. It’s far less interested in the education for which students supposedly attend. […]

The pandemic has made college frail, but it has strengthened Americans’ awareness of their attachment to the college experience. It has shown the whole nation, all at once, how invested they are in going away to school or dreaming about doing so. Facing that revelation might be the most important outcome of the pandemic for higher ed: An education may take place at college, but that’s not what colleges principally provide. Higher education survived a civil war, two world wars, the Great Depression, and the 1918 Spanish flu, the worst pandemic the U.S. has ever faced. American colleges will outlast this crisis, too, whether or not they are safe, whether or not they are affordable, and whether or not you or your children actually attend them. The pandemic offered an invitation to construe college as an education alone, because it was too dangerous to embrace it as an experience. Nobody was interested. They probably never will be.

This is certainly correct, and there’s no doubt that university administrators are paying close attention to the lessons this pandemic has taught. Chief among them, I predict, will be that full-time faculty are so marginal to “the college experience” that there’s no point in paying more than a handful of them — the research stars, primarily in the sciences. The adjunctification of the faculty will continue at an accelerated pace.

October 19, 2020

If Then

There are many books that I admire and love that I never for a moment dream I could have written. Right now I’m reading an old favorite, Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, to my wife, and as I do so I am every minute aware that I could not write this book if you gave me a million years in which to do so.

But every now and then I encounter an admirable book that I wish I had written, that (if I squint just right) I see that I could have written. I had that experience a few years ago with Alexandra Harris’s Weatherland, and I’m having it again right now as I read Jill Lepore’s If Then. What a magnificent narrative. What a brilliant evocation of a moment in American history that is in one sense long gone and in another sense a complete anticipation of our own moment. Oh, the envy! (Especially since if I had written the book it wouldn’t be nearly as good as it is.)

We are afflicted by our ignorance of history in multiple ways, and one of my great themes for the past few years has been the damage that our presentism does to our ability to make political and moral judgments. It damages us in multiple ways. One of them, and this is the theme of my book Breaking Bread with the Dead, is that it makes us agitated and angry. When we, day by day and hour by hour, turn a direhose of distortion and misinformation directly into our own faces, we lose the ability to make measured judgments. We lash out against those we perceive to be our enemies and celebrate with an equally unreasonable passion those we deem to be our allies. We lack the tranquility and the “personal density” needed to make wise and balanced judgments about our fellow citizens and about the challenges we face.

But there is another and still simpler problem with our presentism: we have no idea whether we have been through anything like what we are currently going through. Some years ago I wrote about how comprehensively the great moral panic of the 1980s – the belief held by tens of millions of Americans that the childcare centers of America were run by Satan worshipers who sexually abused their charges – has been flushed down the memory hole. In this case, I think the amnesia has happened because a true reckoning with the situation would tell us so much about ourselves that we don’t want to know. It would teach us how credulous we are, and how when faced with lurid stories we lose our ability to make the most elementary factual and evidentiary discriminations. But of course our studied refusal to remember that particular event simply makes us more vulnerable to such panics today, especially given our unprecedentedly widespread self-induced exposure to misinformation.

Even more serious, perhaps, is our ignorance – in this case not so obviously motivated but the product rather of casual neglect — of the violent upheavals that rocked this nation in the 1960s and 1970s. Politicians and pastors and podcasters and bloggers can confidently assert that we are experiencing unprecedented levels of social mistrust and unrest, having conveniently allowed themselves to remain ignorant of what this country was like fifty years ago. (And let’s leave aside the Civil War altogether, since that happened in a prehistoric era.) Rick Perlstein is very good on this point, as I noted in this post.

All of this brings us back to Jill Lepore’s magnificent narrative about the rise and fall of a company called Simulmatics, and the rise and rise and rise, in the subsequent half-century, of what Simulmatics was created to bring into being. Everything that our current boosters of digital technology claim for their machines was claimed by their predecessors sixty years ago. The worries that we currently have about the power of technocratic overlords began to be uttered in congressional hearings and in the pages of magazines and newspapers fifty years ago. Postwar technophilia, Cold War terror, technological solutionism, racial unrest, counterculture liberationism, and free-market libertarianism — these are the key ingredients of the mixture in which our current moment has been brewed.

Let me wrap up this post with three quotations from If Then that deserve a great deal of reflection. The first comes from early in the book:

The Cold War altered the history of knowledge by distorting the aims and ends of American universities. This began in 1947, with the passage of the National Security Act, which established the Joint Chiefs of Staff, created the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Council, and turned the War Department into what would soon be called the Department of Defense, on the back of the belief that defending the nation’s security required massive, unprecedented military spending in peacetime. The Defense Department’s research and development budget skyrocketed. Most of that money went to research universities — the modern research university was built by the federal government — and the rest went to think tanks, including RAND, the institute of the future. There would be new planes, new bombs, and new missiles. And there would be new tools of psychological warfare: the behavioral science of mass communications.

The second quotation describes the influence of Ithiel de Sola Pool — perhaps the central figure in If Then, one of the inventors of behavioral data science and a man dedicated to using that data to fight the Cold War, win elections, predict and forestall race riots by black people, and end communism in Vietnam — on that hero of the counterculture Stewart Brand:

Few people read Pool’s words more avidly than Stewart Brand. “With each passing year the value of this 1983 book becomes more evident,” he wrote. Pool died at the age of sixty-six in the Orwellian year of 1984, the year Apple launched its first Macintosh, the year MIT was establishing a new lab, the Media Lab. Two years later, Brand moved to Cambridge to take a job at the Media Lab, a six-story, $45 million building designed by I. M. Pei and named after Jerome Wiesner, a building that represented nothing so much as a newer version of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome. Brand didn’t so much conduct research at the Media Lab as promote its agenda, as in his best-selling 1987 book, The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at M.I.T. The entire book, Brand said, bore the influence of Ithiel de Sola Pool, especially his Technologies of Freedom. “His book was the single most helpful text in preparing the book you’re reading and the one I would most recommend for following up issues raised here,” Brand wrote. “His interpretations of what’s really going on with the new communications technologies are the best in print.” Brand cited Pool’s work on page after page after page, treating him as the Media Lab’s founding father, which he was.

And finally: One of Lepore’s recurrent themes is the fervent commitment of the Simulmatics crew to a worldview in which nothing in the past matters, and that all we need is to study the Now in order to predict and control the Future:

Behavioral data science presented itself as if it had sprung out of nowhere or as if, like Athena, it had sprung from the head of Zeus. The method Ed Greenfield dubbed “simulmatics” in 1959 was rebranded a half century later as “predictive analytics,” a field with a market size of $4.6 billion in 2017, expected to grow to $12.4 billion by 2022. It was as if Simulmatics’ scientists, first called the “What-If Men” in 1961, had never existed, as if they represented not the past but the future. “Data without what-if modeling may be the database community’s past,” according to a 2011 journal article, “but data with what-if modeling must be its future.” A 2018 encyclopedia defined “what-if analysis” as “a data-intensive simulation,” describing it as “a relatively recent discipline.” What if, what if, what if: What if the future forgets its past?

Which of course it has. Which of course it must, else it loses its raison d’être. Thus the people who most desperately need to read Lepore’s book almost certainly never will. It’s hard to imagine a better case for the distinctive intellectual disciplines of the humanities than the one Lepore made just by writing If Then. But how to get people to confront that case who are debarred by their core convictions from taking it seriously, from even considering it?

October 13, 2020

hidden features of micro.blog

Micro.blog has some cool features that many users are not aware of. (They’re not really hidden, but that made for a better title than “not especially well-known.”) Here are some of my favorites:

October 12, 2020

simple

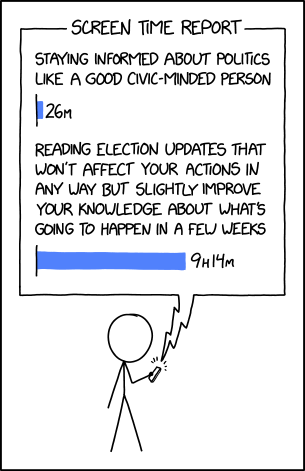

XKCD is rarely wrong, but this:

— this is wrong. During that nine nine hours and fourteen minutes you will not do anything to “slightly improve your knowledge.” You will, instead, gradually become less knowledgeable; any genuine information you might happen on will be methodically and inexorably displaced by misinformation, deliberate twisting of the facts, rumor-mongering, hate-mongering, fear-mongering, and brazenly dishonest personal attacks on anyone and everyone.

If you have any concern whatsoever for acquiring knowledge, you won’t be on social media at all for the next month. It’s as simple as that.

the Great Crumping revisited

A surprising number of readers of my previous post have written out of concern for my state of mind, which is kind of them, but I think they have read as a cri de coeur what was meant as a simple summary of the facts. Not pleasant facts, I freely admit, but surely uncontroversial ones. Stating them so bluntly is just one element of my current period of reflection.

The primary reason I am not in despair is simply this: I know some history. I think we will probably see, in the coming decades, the dramatic reduction or elimination of humanities requirements and the closure of whole humanities departments in many American universities, but that will not mean the death of the humanities. Humane learning, literature, art, music have all thrived in places where they were altogether without institutional support. Indeed, I have suggested that it is in times of the breaking of institutions that poetry becomes as necessary as bread.

Similarly, while attendance at Episcopalian and other Anglican churches has been dropping at a steep rate for decades, and I expect will in my lifetime dwindle to nearly nothing, there will still be people worshipping with the Book of Common Prayer as long as … well, as long as there are people, I think. And if evangelicalism completely collapses as a movement — for what it’s worth, I think it already has — that will simply mean a return to an earlier state of affairs. The various flagship institutions of American evangelicalism are (in their current form at least) about as old as I am. The collapse I speak of is, or will be, simply a return to a status quo ante bellum, the bellum in question being World War II, more or less. And goodness, it’s not as if even the Great Awakening had the kind of impact on its culture, all things demographically considered, as one might suspect from its name and from its place in historians’ imaginations.

This doesn’t mean I don’t regret the collapse of the institutions that have helped to sustain me throughout my adult life. I do, very much. And I will do my best to hekp them survive, if in somewhat constrained and diminished form. But Put not your trust in institutions, as no wise man has even quite said, even as you work to sustain them. It’s what (or Who) stands behind those institutions and gives them their purpose that I believe in and ultimately trust.

The Great Crumping is going on all around me. But if there’s one thing that as a Christian and a student of history I know, it’s this: Crump happens.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers