Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 182

February 3, 2021

Daoism and Cosmotechnics

My recent New Atlantis essay on the way beyond what I call The Standard Critique of Technology is now unpaywalled. This is an important essay for me personally, though I have no idea whether anyone else will find it valuable. It’s peculiar.

The basic question I ask is this: What if Neil Postman and Ivan Illich and Ursula Franklin and Albert Borgmann are all absolutely correct in their critique of how modern technocracy has developed — but as a result nothing has changed? What do we do now?

The basic answer I give is: There may be considerable resources available to us through the philosophical (as opposed to the religious) tradition of Daoism.

It may seem odd that as a Christian I am looking to Daoism, but again, it is to Daoism as a philosophical tradition (daojia) rather than Daoism as an organized religion (daojiao) to which I turn, and Christian thinkers have typically been open to the adaptation of non-Christian sources of thought. If Thomas Aquinas can appropriate Aristotle then I see no reason why I can’t appropriate Laozi. There are certain elements of Christian spirituality — especially from the Franciscan tradition: as I say in the essay, St. Francis is a kind of Daoist sage — that echo the Daoist approach to technology, but they remain, I think, underdeveloped. That’s something I want to work on in the coming years.

January 31, 2021

katharsis culture

A great many people have criticized the use of the term “cancel culture,” but have done so for different reasons. One group of people simply wants to deny that cancellation is a widespread phenomenon; others are aware that something is going on but don’t think that “cancellation” is the right way to describe it. I myself don’t have a problem with the use of the phrase, but I think there are more accurate ways of describing the very real phenomenon to which that phrase points. I think the two key concepts for understanding what is happening are katharsis and broken-windows policing.

In an essay that I published a few years ago, I talked about the prevalence among those committed to social justice, especially on our university campuses, of a sense of defilement. The very presence in one’s social world of people who hold fundamentally wrong ideas about race and justice is felt as a stain that must somehow be scrubbed away. As long as such people are present, one experiences akatharsia: impurity, defilement. The filth must be cleansed, the community must be purged. (I’m choosing the spelling “katharsis” rather than “catharsis” to focus on this archaic meaning.)

This kind of thing is sometimes referred to as scapegoating, but it isn’t, not at all. Essential to scapegoating is the belief that the unclean social order can be made clean by casting out or sacrificing something that is itself pure and undefiled. In the cases I am discussing here, the logic is more straightforward: the one who is perceived to bring the defilement must himself or herself be expelled. Scapegoat rituals have a complex symbolism. Katharsis culture doesn’t.

Now, such katharsis may be accomplished in several ways. Sometimes it involves actions for which the term “cancellation” is the best one: an announced lecture is canceled and the lecturer disinvited, or a television program that had been scheduled is canceled. But katharsis takes many other forms. For instance, James Bennet had to be fired from the New York Times because by authorizing an editorial by Senator Tom Cotton in the newspaper he had defiled its pages. The op-ed itself could not be erased, so, through a compensatory kathartic action, Bennet had to be removed.

Our society has largely forgotten the symbolism of defilement and purgation, so we don’t know how to call it by its proper name. When people feel that they have been defiled, what they can to say is that they feel unsafe. Everyone knows that such people are not in any meaningful sense unsafe; it is a singularly inapt word; but people use it because living in a publicly disenchanted world has deprived them of the more accurate language.

All this explains why Ben Dreyfuss’s preference for the language of “snitching” is not especially helpful. But that word does capture something relevant, which is the way that katharsis culture always involves appeals to authority: rarely do we see attempts at direct action against the sources of defilement — which is good, because that would require the more drastic and clearly illegal actions we saw on January 6 in Washington D.C. Rather, the existing authorities are asked to assume a sacral role and to enact the necessary purging. This return of archaic religious impulse, then, serves to reinforce existing power structures rather than to undermine them, which is why so many leaders accede to the demands of the mob: it’s good for their authority, it establishes them more firmly in place. And also, like George Orwell in “Shooting an Elephant,” they are being driven by the mob which they may seem to be leading, and in the eyes of that mob they can’t bear looking like fools. Thus they are doubly incentivized to carry out the sacral duties of their leadership position.

But there is another element to this behavior that likewise could be described in religious terms but might be more easily graspable if a more mundane analogy is invoked. Those who demand the expulsion from their community, whatever they perceive their community to be, of the producers of defilement do not just address their acts to the presently guilty: they seek to address all of us as well. The message is: Our vigilance is constant and you cannot hope to escape our surveillance. No matter how small or insignificant you are, we will find you and we will punish you. This ceaseless surveillance of public space by self-appointed cops, then, is a kind of broken-windows policing. It’s a way of letting everybody know that the space is watched, the spaces cared for. If trivial offenses are so strictly punished, more serious violators have no hope of escaping undetected.

In this sense, the hyperaggressive and absolutist pursuit of purging the unclean thing – no one ever thinks it adequate for people like James Bennet to be to apologize or to take a leave of absence or even to undergo anti-bias training, they’re always given the ultimate punishment possible – is meant less for the offender of the moment then for all the bystanders: thus Voltaire’s famous line about the British Navy hanging admirals pour encourager les autres. You can see, then, that what I’m calling katharsis culture has a double character, the sacral and the disciplinary. We are all invited to look upon the holy rite — to look, and to tremble.

January 30, 2021

offside, handball, and VAR

Nobody, and I mean nobody, in the world of soccer knows what the offside rule is. Nobody, and I mean nobody, in the world of soccer knows what the handball rule is. What’s called offside in one match will be called onside in another; handball calls are if anything even more arbitrary. And VAR seems to have increased rather than decreased the inconsistency of rulings.

Consequently, the players cannot adjust either their expectations or their performance to meet the ever-changing rules, because changes in the rules don’t affect how calls are actually made, by officials or by VAR.

The only logical response to this ongoing farce is to eliminate VAR. However, FIFA is obviously absolutely committed to VAR, and I cannot see any circumstances in which they would abandon it, despite the almost unanimous hatred of it by players, coaches, journalists, and fans. (The complete insulation of FIFA from the game it is meant to serve is perhaps a topic for another post.)

Therefore, given the inevitable absence of logic, I make the following recommendation: Let VAR go on as it has been going in all other cases, but whenever there is a sniff of a question about handball or offside, VAR will take the form of a coin flip: Heads is offside/handball, tails is onside/no-handball. I think it will be easier for everyone concerned if the pretense of standards is abandoned, and the arbitrariness that actually governs calls is embraced.

Reading this story about an obsessively malicious online ...

Reading this story about an obsessively malicious online troll I’m reminded that when the big tech companies say “We simply can’t monitor all the traffic that we get” what they really mean is “We would rather people’s lives be destroyed than to make hires that would cut into our profits.”

In A Writer’s Notebook (1949), Somerset Maugham wrote: “I...

In A Writer’s Notebook (1949), Somerset Maugham wrote: “I am like a passenger waiting for his ship at a wartime port. I do not know on which day it will sail but I am ready to embark at a moment’s notice. … I read the papers and flip the pages of a magazine, but when someone offers to lend me a book I refuse because I may not have time to finish it, and in any case with this journey before me I am not of a mind to interest myself in it. I strike up acquaintances at the bar or the cardtable, but I do not try to make friends with people from whom I shall so soon departed. I am on the wing.” Maugham died sixteen years later.

January 29, 2021

These are the books I’m teaching this term.

These are the books I’m teaching this term.

Yesterday I posted, and then almost immediately took down...

Yesterday I posted, and then almost immediately took down, a reflection on the most recent public kerfuffle at Baylor. I decided that it deserves more than a brief post, so I am going to try to write something at greater length, as soon as I am able.

January 26, 2021

January 25, 2021

three quotations on journalism

People like [Margaret] Sullivan would have you believe that “balance” is a mandate to give voice to clearly illegitimate points of view, but it’s really about not falling so completely in love with your “values” that you stop caring to avoid mistakes about those who don’t share them, or even just mistakes generally.

By any standard, the press had a terrible four years, from the mangling of dozens of Russiagate tales to scandals like the New York Times “Caliphate” disaster and the underappreciated Covington High School story fiasco. Still, many in the business can’t see how bad it’s been, because they’ve walled themselves off so completely from potential critics.

The point is not to try and convince the most hostile Republicans to tune back into mainstream media outlets. Many of them are unreachable by this point, showing less interest in doing or seeking out better reporting than in using accusations of double standards and hypocrisy to help build support for the right and attempt to tear down liberal institutions. Some go even further, to use the failings of professional journalism as a justification for pedaling deliberate distortions on alternative platforms. Those who take this position view all so-called news as a form of propaganda or information warfare and defend the deliberate promulgation of lies as a tit-for-tat response to the actions of their enemies: “If the left does it, then so should we, and with even less restraint.”

But there are plenty of Americans situated between the burn-it-all-down hyper-cynical right and the journalists and Democratic Party politicos who naively or enthusiastically passed around the CNN story last week. Whether the right succeeds in persuading more and more people to join them in tuning out mainstream journalism will depend in large part on whether its accusations of dishonesty and bad faith look accurate to observers. Does the media seem fair-minded and scrupulous in what it labels news? Or does it seem highly invested in enhancing the power of one side in our country’s deep political divide?

The media practicing postjournalism produce nothing else but the donating audience through the manufacture of its anger. Their agenda production entails no consumption. Nobody learns news from this agenda. It does not even have any impact on the assumed audience. Real propaganda involves the proliferation of ideas and values. However, postjournalism cannot do even that. Those whom it is supposed to reach and convert are already trapped in the same agenda bubble.

The only “others” for the agenda bubble, made of the donating audience and their media, are the inhabitants of the opposite agenda bubble on the other side of the political spectrum. Paradoxically, postjournalism supplies not so much content but, rather, the reason for the foes’ existence and their motives, which justify their outrage and mobilization. However, there is also no expected agenda impact on opponents. The opponents do not consume ‘opposing’ content as information. They regard it as a source of energy to feed their anger. Polarization is the essential environmental condition and the only outcome of postjournalism (besides the earnings of the media that practice postjournalism).

Because of its self-containment and the need for energy input, postjournalism exists in a binary form in which the strength of the one side depends on the strength of the other. Their confrontation strengthens their audience-capturing power and maintains their business.

the three paths

The active life:

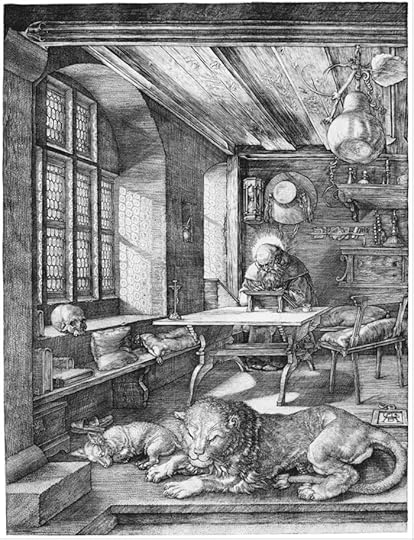

The contemplative life:

The social-media life:

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers