Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 121

April 23, 2022

a tiny rant

Recently I listened to a highly-regarded political podcast in which some of the participants referred to Senator Fine-Stine while others spoke of Senator Fine-Steen. I have several thoughts:

Any journalists who plan to talk about a person for half an hour in public have a positive moral obligation to decide in advance how that person’s name is to be pronounced. It is not difficult to discover how Senator Feinstein pronounces her name, so what does it say about journalists’ commitment to their job when they can’t be bothered to find out? The mispronunciation some of them chose is not just wrong but indefensible, because the syllable -ein cannot legitimately pronounced one way in the first half of a name and a different way in the second half of the name. I blame Leonard Bernstein for this confusion. As far as I know, he is the first famous American with a name ending in -stein who chose to pronounce it -steen. Now it’s a question for everybody in the same nominative condition.Note, though, that there’s never a debate when someone’s name begins with Stein or simply is Stein. I think we should all pronounce names that end with -stein the correct way (the Einstein Way, let’s call it) (the Ein Steinway?) and if anyone with such a name wants to pronounce it -steen we should tell them that they’re wrong and refuse to comply.Michael Chabon (2006):I don’t know what happened to the F...

I don’t know what happened to the Future. It’s as if we lost our ability, or our will, to envision anything beyond the next hundred years or so, as if we lacked the fundamental faith that there will in fact be any future at all beyond that not-too-distant date. Or maybe we stopped talking about the Future around the time that, with its microchips and its twenty-four-hour news cycles, it arrived. Some days when you pick up the newspaper it seems to have been co-written by J. G. Ballard, Isaac Asimov, and Philip K. Dick. Human sexual reproduction without male genetic material, digital viruses, identity theft, robot firefighters and minesweepers, weather control, pharmaceutical mood engineering, rapid species extinction, US Presidents controlled by little boxes mounted between their shoulder blades, air-conditioned empires in the Arabian desert, transnational corporatocracy, reality television — some days it feels as if the imagined future of the mid-twentieth century was a kind of checklist, one from which we have been too busy ticking off items to bother with extending it. Meanwhile, the dwindling number of items remaining on that list — interplanetary colonization, sentient computers, quasi-immortality of consciousness through brain-download or transplant, a global government (fascist or enlightened) — have been represented and re-represented so many hundreds of times in films, novels and on television that they have come to seem, paradoxically, already attained, already known, lived with, and left behind. Past, in other words.

April 22, 2022

injured

My Hedgehog Review essay “Injured Parties” — on free speech, iniuria, charity, social and legal remedies, and strategic inattention — is unpaywalled, so please read!

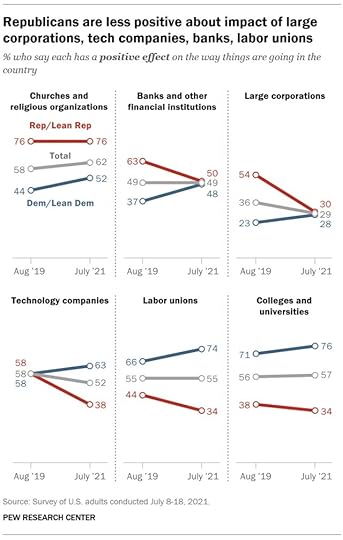

institutions

Story here. See also my essay on the need to recover the virtue of piety in order to restore institutions. But we have a really bad feedback loop here: as our institutions become more explicitly committed to leftish values, or what pass for leftish values these days, then Republicans and conservatives grow more alienated from them; but it’s also true that those institutions became more committed to leftish values because Republicans and conservatives were already disinclined to invest trust and energy in them. So we’re in a kind of death spiral here and I don’t see a way out of it.

Also: the fact that Republicans have a positive opinion of churches doesn’t mean that they are willing to serve and strengthen churches. Opinions are cheap, service is costly.

entanglements

Science gets entangled with politics; it always has and it always will. And every time it happens the reputation of science get damaged. I am of course not a scientist and cannot speak authoritatively to these matters; but I can at least point to some intellectual problems that need to be addressed.

Two recent examples:

Jesse Singal describes a study on gender-transitioning teens that discovered that “the kids in this study who accessed puberty blockers or hormones … had better mental health outcomes at the end of the study than they did at its beginning” — or did they? Apparently not. Signal can’t be certain about this because the researchers have hidden their data, but their claims look pretty darn fishy. Even so, no one in the media is going to ask hard questions because the study says exactly what they want to hear. In the New York Review of Books, a biologist and a historian review a new book on the genetics of intelligence. They don’t like the book because they think that the idea of “a biological hierarchy of intelligence” has been repeatedly “discredited” and is not supported by the arguments of the book under review. But here too a great many complex questions are oversimplified or simply ignored, as Razib Khan points out.The study on trans kids and the NYRB review share a core conviction: Scientific studies that could lead to unfavorable social outcomes by providing support for our political enemies must be denounced and their authors shunned. As Stuart Ritchie has commented on the latter contretemps,

It’s dispiriting to think that our public debate on genetics is going to be forever hobbled by this kind of thing, and from ostensibly authoritative sources. Other fields like evolutionary biology, climate science, and immunology have their creationists, climate change deniers, and antivaxxers, but they’re not usually Stanford professors. In this area, the nuisance call — the nihilist call, encouraging us to cut off our entire scientific nose to spite our behaviour-genetic face — is coming from inside the house.

But again, this is an old story — especially in the NYRB. When E. A. Wilson’s Sociobiology came out in 1975, a group of scientists wrote to the NYRB to denounce it, and were quite explicit about why it had to be denounced: Theories like Wilson’s “consistently tend to provide a genetic justification of the status quo and of existing privileges for certain groups according to class, race or sex.” Wilson’s purpose, they said, was to “justify the present social order.” Wilson replied with a detailed refutation of their claims about him personally — “Every principal assertion made in the letter is either a false statement or a distortion. On the most crucial points raised by the signers I have said the opposite of what is claimed” — but this didn’t slow his opponents’ crusade against his ideas, because even if Wilson didn’t hold lamentable political views, others certainly do, and might well use sociobiological arguments to buttress their regressive policy ideas.

(One of Wilson’s collaborators, Bert Hölldobler, says that Richard Lewontin was quite explicit about this: “When I asked why he so blithely distorted some of Ed’s writings he responded: ‘Bert, you do not understand, it is a political battle in the United States. All means are justified to win this battle.’” That sounds suspiciously pat to me, but it certainly wouldn’t be surprising coming from Lewontin.)

Thus, in 1979, when the NYRB published a strongly critical review by Stuart Hampshire of a later book by Wilson, the same people who had so strongly denounced Wilson four years earlier wrote to complain about Hampshire’s review. Hang on: they complained about a negative review of Wilson? Yes indeed:

Hampshire neglected the social and political issues which are at the heart of the sociobiology controversy. Three years ago many of us wrote a letter in response to a review of E.O. Wilson’s earlier book, Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, in which we pointed out the political content of this new field. We expressed concern at the likelihood that pseudo-scientific ideas would be used once more in the public arena to justify social policy. The events of the intervening years have fully justified our initial fears.

Again, I can’t adjudicate the scientific questions at issue here; I am making a different point, which is this: Wilson’s critics are quite explicit that what really matters to them is not the philosophical naïveté or scientific inaccuracy of Wilson’s work but its anticipated political consequences. So it seems quite likely that if Wilson’s work had been philosophically sophisticated and scientifically unimpeachable their critique would not have changed.

Of course, many similar stories can be told — and have been — about Covidtide, during which “trusting The Science” was an absolute imperative: as knowledge grew what counted as The Science changed, but at any given moment you were compelled to insist that (a) The Science is infallible and (b) The Science supports people like me against our political enemies.

There are many reasons why millions of America don’t trust The Science, including belligerence and ignorance, but if you ask me, I would say that the most important reason is illustrated by the stories above: Scientists are sometimes untrustworthy. If they want to rebuild our trust in them, then they should start with three steps:

Practice the self-critical introspection that would enable them to perceive that, because they are human beings, there are some things they very much want to believe and some things they very much want to disbelieve; Acknowledge those preferences in public; Show that they are taking concrete steps to guard themselves against motivated reasoning and confirmation bias.If scientists and science writers were to take such steps, that would be helpful for us as readers; and even better for them as thinkers and writers.

April 21, 2022

hero

Wingy Manone was a trumpet player and songwriter from New Orleans who lost part of his right arm in a streetcar accident when he was ten years old. For the rest of his life he wore a prosthetic arm, and at some point had one made with a special compartment for which he had one use: to stash his famously excellent weed.

The courtyard of Kéré Architecture’s Léo Doctors’ Housing...

The courtyard of Kéré Architecture’s Léo Doctors’ Housing, 2019, at the Surgical Clinic and Health Center, Léo, Burkina Faso; described here. Kéré’s “emotional and moral attachment to his humble roots remains strong, and although one has seen other gifted architects morph from self-effacing aspirants into egomaniacal divas, it seems to me improbable that his head will be turned by the tidal wave of adulation that the Pritzker Prize inevitably unleashes. How judiciously he picks and chooses among the many offers that will now come his way — including such typical Pritzker-winner bait as condos in New York’s Chelsea and Miami’s Brickell districts, boutiques for LVMH luxury brands, and wineries for tech billionaires — will indicate how well Francis Kéré can handle the double-edged sword that is architectural fame in our money-worshiping, celebrity-besotted modern world.”

Ross Douthat, suggesting two ways to reverse the decline ...

Ross Douthat, suggesting two ways to reverse the decline of the power and influence of movies:

First, an emphasis on making it easier for theaters to play older movies, which are likely to be invisible to casual viewers amid the ruthless presentism of the streaming industry, even as corporate overlords are tempted to guard classic titles in their vaults.

Second, an emphasis on making the encounter with great cinema a part of a liberal arts education. Since the liberal arts are themselves in crisis, this may sound a bit like suggesting that we add a wing to a burning house. But at this point, 20th-century cinema is a potential bridge backward for 21st-century young people, a connection point to the older art forms that shaped The Movies as they were. And for institutions, old or new, that care about excellence and greatness, emphasizing the best of cinema is an alternative to a frantic rush for relevance that characterizes a lot of academic pop-cultural engagement at the moment.

One of my formative experiences as a moviegoer came in college, sitting in a darkened lecture hall, watching “Blade Runner” and “When We Were Kings” as a cinematic supplement to a course on heroism in ancient Greece. At that moment, in 1998, I was still encountering American culture’s dominant popular art form; today a student having the same experience would be encountering an art form whose dominance belongs somewhat to the past.

This is an odd argument to hear for someone of my generation — aren’t the movies the very thing we’re supposed to save Culture from?

I think maybe that’s why I have grown so fascinated by movies in recent years — I always most enjoy the media that the rest of the world has left behind.

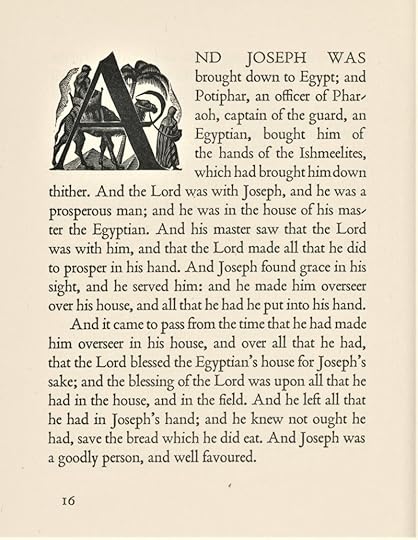

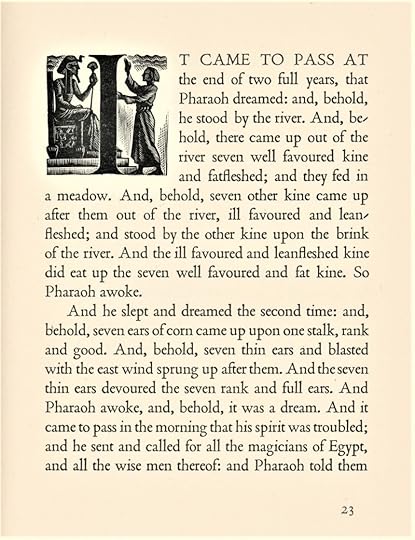

Nora S. Unwin (1907-1982), engravings from Joseph; the Ki...

Nora S. Unwin (1907-1982), engravings from Joseph; the King James Version of a Well-loved Tale, arranged with an introduction by her friend and frequent collaborator Elizabeth Yates, and printed and bound by the Plimpton Press in 1947 for Alfred A. Knopf in America and the Ryerson Press in Canada. From the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Special Collections.

April 20, 2022

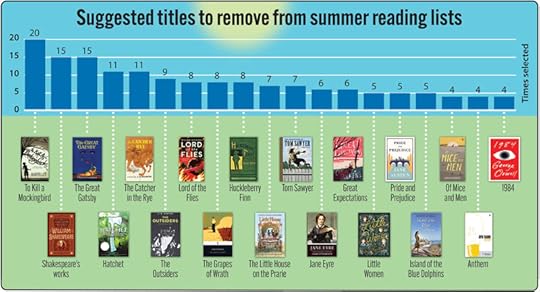

reading lists

Three brief thoughts on this:

People are calling it “banning books,” which it ain’t: a book isn’t banned by being left off a reading list; One teacher says, “I think it’s time to allow books published from the 2000s to be given a fair shake” — because sure, the big problem with our society today is that we just don’t give a “fair shake” to new things; Of the nineteen books listed above, eleven of them were published between 1925 and 1967 — nine between 1938 and 1960 — which suggests a certain constriction of imagination and the dominance in teachers’ minds of a quite brief period in our cultural history.Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 529 followers