Laurent Dubois's Blog, page 94

October 17, 2013

The Two Escobars

Since we have been discussing South American dictatorship and the role of soccer in South American politics, I thought it would be interesting to share this great documentary titled The Two Escobars. It is the stories of Andrés Escobar, a defender on the Columbian national team in the 1994 World Cup, and Pablo Escobar, a Columbian drug lord who financed the development of Columbian soccer through cocaine trafficking in his Medellín cartel. Interestingly, Pablo owned the soccer team that Andrés represented and he supported Andrés in his ascension as a popular figure in Columbia. After Andrés conceded an own goal against the United States, Columbia lost the match and failed to advance past the group stages. When Andrés played down the loss by stating that it was “not the end of the world”, he was shot to death in Medellín. Humberto de la Calle, the Colombian president at the time responded saying, ”Colombia’s problem is that football is no longer a sport, it seems, but a matter of life and death.”

Thus, the film goes on to delve into the complex relationships between politics, sport, and crime. I thoroughly enjoyed the documentary style investigation of this intersection of sport and national politics portrayed on a global stage through the World Cup. To learn more about Columbian Soccer, there is a great article by Courtney Ginn on the Soccer Politics Blog detailing these national issues and offering great insights into the state of affairs at the time.

1- http://espnfc.com/columns/story/_/id/...

Soccer for Everyone

I grew up in central Indiana, and despite the fact that we had an amazing soccer team in high school, there were maybe fifteen students at the state quarter finals, which we lost. So imagine my shock when I found out that Indianapolis was joining the North American Soccer League with their own team, IndyEleven. Sure, we all played little league outside our suburban homes. But soccer in the midwest remains largely a niche sport, not nearly as popular as football, and it doesn’t hold a candle to Indiana’s trademark sports: basketball and NASCAR racing.

Yet somehow, in 2014, Indianapolis will have its own team, owned by Keystone Construction Corporation’s president Ersal Ozdemir, a Turkish immigrant who found his home in Indianapolis. It’s already recruited its first player: the German goalie Kristian Nicht. Although the intention of the Indiana team was to have big ties to Indiana, they’re starting to recruit from all over. At their first try-outs, 90% of players were from the state. Since then, players have come from all over the world to throw their hat into the ring for this tiny team. And 6,000 season tickets have already been sold.

But the club is not without problem. Indianapolis doesn’t have a soccer stadium; IndyEleven will share IUPUI’s already existing soccer fields. In addition, one of its prospective players, Felix Achoch, was killed outside of a night club just days before his try-out. And finally, the club will have to overcome the lack of soccer fanaticism that the club’s owner desires to create. The club’s owner has expressed a desire to appeal to youth and high school teams in urban Indianapolis. But looking at the IHSAA state champions over the past twenty years, winners tend to be Indianapolis private schools or public schools in wealthy suburbs. It’ll be hard to connect with high schoolers who already see soccer as less important than other sports.

But in spite of this, owners, coaches, and the one player currently on the team remain optimistic about the sport in Indiana. Their season starts in the spring of 2014, and only time will tell if a professional soccer team has actual staying power in city ruled by the warring houses of Bobby Knight and Dario Franchitti.

October 16, 2013

L’impulsion de Luis Suarez

On écoute souvent des footballeurs qui sont suspendus pour avoir enfreindre un règlement. Après ce type de transgression, il y a des suspensions et des sanctions que suivre. Quelques footballeurs qui ont été réprimandé incluent Ashley Cole et John Terry. Mais récemment Luis Suarez a été à la front ligne de ce type de scandale.

Le 24 avril, Luis Suarez, l’Uruguayen natal de 26 ans, était suspendu 10 matches par la Fédération anglaise du football. L’attaqueur du Liverpool était suspendu après avoir mordu le bras défendeur du Chelsea, Branislav Ivanovic la saison dernière. Sa suspension était un grand scandale car le club des Reds a pensé que la sanction était trop sévère. Mais c’est incident n’était pas le premier de ce type et on doit se demander si ces types d’incidents continueront car le passé et la réputation de Suarez n’indique pas qu’il est capable de jouer sans attirer le drame. Autres évènements qu’on terminer avec sanctions et suspensions inclut :

En 2010, « le pistolero » était suspendu 7 matches pour avoir mordu autre adversaire. En 2010, son indiscrétion a été amendée par son club et avec une sanction de 235,00 Euros.

Il y a deux saisons, Suarez avait reçu autre sanction de 8 matches pour avoir insulté Patrice Eyra en le disant commentaires racistes.

La carrière turbulente du Suarez indique qu’il n’arrêtera pas d’être suspendu. Mais une chose est claire, Liverpool a besoin de Suarez. Même s’il était aussi clair que Suarez avait voulu quitter Liverpool pour joindre l’Arsenal, puisque Liverpool n’a pas accepté l’offert de l’Arsenal, il paraît que tout a été oublier est que l’équipe est plus qu’heureux de l’avoir jouer. Maintenant il paraît que le récent retour du Suarez, l’actuel deuxième meilleur buteur de Premier League, sera monumental pour les Reds.

October 15, 2013

The Impact of FIFA World Rankings

After the conclusion of the World Cup, a new cycle of FIFA World Rankings begins. Every month, FIFA releases an updated list ranking every national football team — #1 to #207. For most fans, myself included, these rankings seem arbitrary. What does it matter that Croatia is ranked #10 and USA is #13? What does that even mean? Portugal has 1029 points compared to Mexico’s 839. So what? How does FIFA arrive at these point totals? Well, after scouring the internet and solving some middle-school-level math equations, I’ve finally figured out how it all works. To my surprise, it actually makes sense. I could attempt to summarize and simplify the process, but FIFA actually does a pretty good job with explaining how they arrive at each team’s point total.

The basic logic of these calculations is simple: any team that does well in world football wins points which enable it to climb the world ranking.

A team’s total number of points over a four-year period is determined by adding:

· the average number of points gained from matches during the past 12 months;

and

· the average number of points gained from matches older than 12 months (depreciates yearly).

Calculation of points for a single match

The number of points that can be won in a match depends on the following factors:

• Was the match won or drawn? (M)

• How important was the match (ranging from a friendly match to a FIFA World Cup™ match)? (I)

• How strong was the opposing team in terms of ranking position and the confederation to which they belong? (T and C)

These factors are brought together in the following formula to ascertain the total number of points (P).

P = M x I x T x C

The following criteria apply to the calculation of points:

M: Points for match result

Teams gain 3 points for a victory, 1 point for a draw and 0 points for a defeat. In a penalty shoot-out, the winning team gains 2 points and the losing team gains 1 point.

I: Importance of match

Friendly match (including small competitions): I = 1.0

FIFA World Cup™ qualifier or confederation-level qualifier: I = 2.5

Confederation-level final competition or FIFA Confederations Cup: I = 3.0

FIFA World Cup™ final competition: I = 4.0

T: Strength of opposing team

The strength of the opponents is based on the formula: 200 – the ranking position of the opponents

As an exception to this formula, the team at the top of the ranking is always assigned the value 200 and the teams ranked 150th and below are assigned a minimum value of 50. The ranking position is taken from the opponents’ ranking in the most recently published FIFA/Coca-Cola World Ranking.

C: Strength of confederation

When calculating matches between teams from different confederations, the mean value of the confederations to which the two competing teams belong is used. The strength of a confederation is calculated on the basis of the number of victories by that confederation at the last three FIFA World Cup™ competitions (see following page). Their values are as follows:

UEFA/CONMEBOL = 1.00 CONCACAF = 0.88

AFC/CAF = 0.86 OFC = 0.85

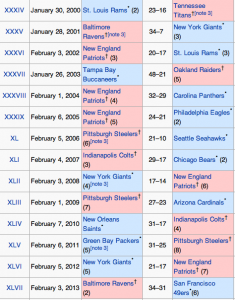

So, now that we understand the math, we can talk about the bigger issue — the impact of the FIFA World Rankings on the World Cup. First, it is important to explain how the World Cup draw works. There are 32 teams that play in the World Cup — 8 group of 4. To determine which nations end up in which group, one pot is created of the top 7 nations, ranked by FIFA, and the host nation, in this case, Brazil. The remaining 24 teams are placed in pots separated by “geographic and sports criteria“.

By being one of the top 7 teams, a nation is arguably given an easier road to advance as they do not have to play the 7 other FIFA-ranked “soccer-powerhouses” in group play. Thus, besides qualifying for the World Cup, every nation’s goal is to be one of the top 7 seeds.

This year’s World Cup seeding hinges on the upcoming October 17th FIFA World Rankings. As of today’s World Cup qualifying matches, Brazil, Spain, Argentina, Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland (right?! who would of thought?) have all clinched a seed for the World Cup finals draw. Fighting for those last two spots are Colombia, Uruguay, Netherlands, and Italy. .

To say the least, the entire process is not easy. While there are a lot of factors and variables that go into the FIFA World Rankings, there is just as much ambiguousness when it comes to how these rankings are employed. The last several qualification matches will determine the final rankings and where each nation will end up. The 2014 World Cup Draw will take place December 6th.

Click Here for more information on the FIFA World Rankings.

October 11, 2013

Flattering to Deceive: Mexico’s History of Unfulfilled Potential

cross-posted from

Friday’s CONCACAF qualifying matches will go a long way to clarifying who will represent the region in 2014 in Brazil. The United States and Costa Rica are already in, while a victory for Honduras would see it grab a spot in the intercontinental playoffs at worst. But by far the most fascinating match of the day is the Mexico-Panama match at the Estadio Azteca. If Panama defeats Mexico—once unthinkable—two things will happen: the canaleros will effectively sew up the playoff spot, moving Panama closer than it ever has been to a berth in the World Cup finals (it is one of only five Latin American nations—the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Venezuela being the others—that have never played in the World Cup); and it would mean that el Tri would likely miss the World Cup for only the fifth time in its history—and the first time since 1990, when the cachirules scandal (discussed below) saw all Mexican teams banned from international play.*

That Mexico might miss the World Cup with its present team seemed unthinkable at the start of qualification. With players like Chicharito and Giovani dos Santos, Andrés Guardado, Pablo Barrera**, and Carlos Salcido—who ended 2011 with a scintillating come from behind win in the Gold Cup—combining with the 2012 Olympic gold medal squad, Mexico should have been battling with the United States for the top spot in the hexagonal rather than fighting for its life. But somewhere along the way the Mexican squad (and its former coach José Manuel “Chepo” de la Torre) lost the script, and the promise held by the team dissipated. The once impregnable Estadio Azteca, where El Tri had lost only once in qualifying between 1961 and 2013 now seems like just another stadium: Mexico has not won a game at home in the hexagonal, tying three times and losing to Honduras.

The fact is that Mexico, long dominant on the regional scale, has rarely translated that success onto the global stage. Mexico’s soccer promise, we might say, often goes unfulfilled. The same might be said of the country: from the Mexican Revolution to the discovery and nationalization of vast oil reserves the Mexican people have been promised much, yet poverty and inequality remain the norm. Indeed, according to Manuel Seyde, Mexico’s few triumphs and “more common disappointments” result in the country and its soccer being “gripped by insecurities.” Its fate, both in sports and otherwise, is to be “a giant in its region and a shadow in the rest of the planet.” (1)

Regional Promises, Globally Broken

The Mexican national team disembarked in Montevideo on a chilly winter day in July 1930. The weather did not improve for the first game Mexico played in the inaugural World Cup. If the national team blamed the weather for its 4-1 loss to France, it could not do the same for its next two games: a 3-0 loss to Chile and a 6-3 defeat at the hands of eventual runner-up Argentina. Called “primitive” by the Argentine press, Mexico finished last in the tournament and allowed the most goals. This certainly was an inauspicious start to the Mexico’s World Cup history. In truth, the federation should not have been surprised by the outcome. The Mexican team had practiced little before departing for Uruguay, and arrived in Montevideo after a 26-day voyage only two days before its first game.

This was not Mexico’s first foray into international soccer. In fact, while national leagues helped bring the country together after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), across the 1920s international play served to bring the nation together as well. In 1922 a Mexican team, primarily made up of the amateur team América, traveled to Guatemala for a three game series, defeating their hosts in two games and tying one. (2) A year later, Mexico again defeated the guatemaltecos, this time at home. These successes created a surge in popularity for the sport. Tours by foreign teams to Mexico, which began in the late 1920s, also led to greater interest in the game, as Mexicans turned out in droves to see how their teams would fare against those from Spain, Chile, and Uruguay. Generally, Mexican teams lost. And while the Tricolor had success in regional championships such as the Central American championships, in international play outside the region, Mexico lost too. The squad that represented Mexico in the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, for example, lost both of its matches: 7-1 to Spain and 3-1 to Chile. And though el Tri met success in qualifier matches for the 1934 Cup—defeating Cuba three times—it failed to qualify for the finals, traveling to Rome to lose a play-in game against the United States. Indeed, the Tricolor rarely represented itself well in international tournaments. Between 1930 and 1958, Mexico participated in four of six World Cups, managing only one tie. In 1962 Mexico finally earned its first victory in the World Cup, but that hardly changed its fortunes. El Tri failed to win a game in 1966, and did not qualify for the 1974 or 1982 championships. Nevertheless, notwithstanding Mexico’s poor showings, international play helped to popularize soccer and forge a sense of identity. Indeed, with the exception of nationalizing oil in 1938, soccer was perhaps the most important symbol around which all Mexicans could unite. And eventually the outcomes of Mexico’s matches improved.

Mexico, 1970

The World Cup of 1970 offered an opportunity for unity in Mexico, especially after the 1968 Olympic Games. In soccer terms, perhaps, this opportunity was lost. It is often, though not always, the case that host nations advance farther in the World Cup than they might otherwise. Until South Africa’s crash in 2010, no home team had failed to make it out of the first round. Sweden, for instance, lost the 1958 finals against Brazil. Four years later, Chile, which likely would not have qualified for the championship were it not the host, finished in third place. England too, a perennial quarterfinalist, won the trophy at home in 1966, but has only reached the semifinals one other time. So hosting the Cup and finishing sixth, as Mexico did in 1970, should be seen as a lost opportunity. But in placing Mexico on the world stage, hosting the Cup promised—and in part delivered—much.

The Mexico team that contested the World Cup in 1970 hoped for better. A strong side, the team raised expectations with a slate of games in early in the year. From February until April Mexico played twelve matches, winning five, drawing five, and losing only two. With one exception, all of the matches were against teams that had qualified for the World Cup. And Mexico started the tournament well, if uninspired, with a goalless draw against the Soviet Union. From there, things began to look up. The Tricolor followed this match with two victories, over El Salvador and Belgium, to qualify for the knockout phase of the tournament for the first time. It was no small achievement. The team advanced with a certain amount of panache, scoring five goals and allowing none. And the quarterfinal match against Italy, played in Toluca, got off to a flying start for the Mexican team, as the Tricolor took the lead in the twelfth minute. Footage of the game shows the team celebrating the goal along with delirious fans. The joy would be short-lived. In the twenty-fifth minute, Italy scored, deflating the stadium’s energy. In the second half Italy scored three more, ending Mexico’s World Cup dreams.

But the hopes born from the 1970 World Cup related to more than soccer. Rather, as it had with the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, the Mexican government had hoped to use a world sporting event to project the image of a developed and modern Mexico. Both events highlighted Mexico’s ability to plan a worldwide event and, to paraphrase historian Eric Zolov, temporarily replaced the myth that Mexico was a land of mañana—where nothing got done—with the notion that it was the land of tomorrow, where anything was possible. All of the advance planning for 1968, however, came to naught. The Mexico City Olympics are remembered not for the transformation of the capital city into a gleaming, friendly, modern metropolis, but for the massacre of student protesters in the Tlatelolco square and the black power salute of Tommie Smith and John Carlos. (3) By contrast, though the Mexican soccer team failed to make it past the quarterfinals in 1970, Mexico scored high marks for hosting one of the most memorable World Cups. Indeed, for Mexican commentators, the Cup suggested the country’s potential to enter the ranks of developed nations. It represented, in other words, a promise for the future.

1986 and 1990

Within years, however, that promise evaporated in the midst of the boom and bust cycle of the Mexican economy. Economic growth in the decade was offset by rampant inflation and the oils crisis. Discovery of new oil reserves in the 1970s led to higher government borrowing, and when the price of oil plummeted, the Mexican economy collapsed. Yet, in the midst of the “lost decade”, as the economic crisis of the 1980s is known, Mexico hosted another mega event. The World Cup in 1986 was supposed to be held in Colombia, but missed construction deadlines and a simmering civil conflict caused the country to renege on its organizing responsibilities. FIFA reopened bidding for the right to host, and Mexico beat out bids from the United States and Canada. In so doing, Mexico became the first country to host the cup for the second time, causing a surge in nationalist pride and raising spirits in the midst of financial gloom. Moreover, the Mexican government invested millions of dollars to present the country as modern and developed once again.

In the year before the tournament, Mexico’s soccer star shone brightly even as its economy teetered. Throughout 1985 the team appeared nearly invincible, losing only four of twenty-two games. Mexican hopes for a strong showing at the World Cup seemed attainable; a good showing in soccer would doubtless buoy the national sentiment. And then, disaster struck. On the morning of September 19, 1985, eight months before the World Cup was to begin, an 8.0 magnitude earthquake struck off the west coast. Between 10,000-40,000 people died and thousands of buildings were damaged in Mexico City alone. But none of the twelve existing stadiums had been damaged by the quake and all of the new structures built for the event had also escaped damage. Nevertheless, Mexico found itself having to run a World Cup in the midst of a massive reconstruction effort, just as Chile had done twenty-four years earlier. Strong aftershocks, over 7 on the Richter scale, could still be felt one month before the tournament began.

The 1986 World Cup is remembered mainly for the audacity of Diego Maradona. In the quarterfinal match against England he scored two goals: the infamous “hand of God” goal and also his stunning run through the entire British defense to score what many say is the greatest goal of all time. But there are other stories from that Cup: Mexico’s disallowed goal in the quarterfinal against Germany; Manuel Negrete’s beautiful goal, which would have been the best of the tournament had it not been for Maradona. Here is another. The Mexican team took the field for its first game in the 1986 World Cup at the Estadio Azteca in front of over 100,000 fans. As Hugo Sánchez, Tomás Boy, Manuel Negrete, and the rest of the Tricolor stood waiting for the national anthem to start, the sound system failed. Instead, the majority of the fans serenaded the national team.

As a result of its excellent outcomes in the lead up to the World Cup, expectations for the Mexican team were high. Hugo Sánchez, then a 28-year old phenomenon, had just won his second consecutive Spanish league scoring title (pichichi) with Real Madrid, and he led a formidable team. And they performed well. Belgium posed no threat, with Mexico taking a 2-0 lead and holding on to win 2-1. A rough game against Paraguay ended in a 1-1 draw, and Mexico navigated around a weak Iraq, 1-0. For only the second time, Mexico was through to the knock out stages. There, el Tri would meet Bulgaria, waltzing to a 2-0 win. In the quarterfinals, a hard fought match against eventual runner-up West Germany showed Mexico’s grit and determination. The game ended in a 0-0 draw—with a goal by Mexico controversially disallowed—with Germany winning on penalty kicks. Once again, Mexico’s soccer promises had gone unfulfilled.

Yet the future appeared to bode well. They could not fail to build off the experience and improve their performances by the time that Italy hosted the next Cup in 1990. Indeed the 1990 competition was supposed to be a coming out party for Mexico: Sánchez would be 32, hardly an old man, while Negrete would just be 31. More, younger players like Carlos Hermosillo and Alberto García Aspe would be ready to take over. And the team wanted to prove that 1986 had been no fluke. The promise of the generation, of Mexican soccer finally arriving as a force to be reckoned with, awaited fulfillment. It was not to be, due to the machinations of the Mexican Fútbol Federation.

Cachirules

The cachirules scandal is one of the biggest to ever hit a national team involving not so much players as the highest heights of Mexican soccer. In 1988, during the qualification process for the 1989 Under-20 World Championship in Saudi Arabia, the Mexican newspaper Ovaciones published an article accusing the youth team of using over aged players. At first, Mexican soccer officials denied the charges. But the Mexican press continued to run stories about the case, and was only too happy to oblige when federation president Rafael del Castillo demanded to see proof. The journalists disclosed that the FMF’s own age registry showed that at least four of the players were too old to play. Two players exceeded the limit by two years, one by three years, and the fourth was seven years older than he claimed. The scandal grew. Other national soccer federations demanded that CONCACAF take decisive steps to punish Mexico. CONCACAF’s disciplinary panel decided to ban the Mexican team from the Saudi tournament and imposed lifetime bans on the FMF executive council members. (4)

Hoping for a more favorable hearing in front of the FIFA disciplinary board, del Castillo appealed the ruling to Zurich. There, however, he received a harsher rebuke. Instead of earning a reprieve for the Mexican youth team, FIFA banned all Mexican teams from FIFA tournaments for two years and upheld the ban on the FMF executive council. Mexico, with a stunningly talented squad, would miss the 1988 Olympics in Seoul—for which they had already qualified—and the 1990 World Cup in Italy. Both Mexican soccer fans and commentators around the world had expected the team to challenge for the cup. Hugo Sánchez, fresh off tying the Spanish record for goals in a season (38) for Real Madrid, would be back. Carlos Hermosillo, who had scored 24 goals the previous season in the Mexican leagues, was on the squad. With that tandem Mexico would have been difficult to stop, a fact that they proved in the year prior to the tournament. While el Tri had been banned from official tournaments, it could still play friendly matches. Prior to the World Cup, other teams sought games with the talented Mexican squad to warm up against quality opposition. Mexico played five teams headed to Italy: Argentina, the reigning world champion; Colombia; South Korea; the United States, and Uruguay. El tri won all five of these games. Another promise unfulfilled.

Et tu Chicarito?

So where does this leave us going into the last matches of the hexagonal? I would suggest that it leaves fans of the tricolor in an all too familiar place: waiting for disappointment. For all the promise of the Tricolor, Mexican soccer fans are used to teams failing to reach their potential. The generation of Hugo Sánchez and Carlos Hermosillo was supposed to go farther than the quarterfinals and then lost its chance at redemption in 1990 due to an inept and corrupt bureaucracy. So too the 1994 edition of the squad (with Cuauhtémoc Blanco, Luis Hernández, and Jorge Campos) promised Mexican greatness. Indeed, this seems to be the narrative of Mexican soccer history and Mexico itself: destined for greatness that, sometimes through no fault of its own, remains just out of reach. And now the hopes of the so-called golden generation—with established players like Chicharito, dos Santos, Salcido, and Rafa Marquez and the newer additions such as Marco Fabian, Javier Aquino, Hiram Mier and Miguel Layún—hang by the slimmest of threads. At the start of qualification, many Mexicans believed that this team represented the best chance that el Tri had to finally bring home the World Cup and to show that Mexico could compete on the world stage. Now they have to wait to see: will this group of players salvage the campaign and qualify, or will it collapse under the pressure of expectation.

Anthropologist Roger Magazine has suggested that Mexico lacks a “prominent national mythology” about the national soccer team. Mexicans, he argues, “closely scrutinize the performance of the national team” but do not use it as a measuring stick for the nation. (5) This may indeed be true. But perhaps this curiosity, the lack of investment in the team, comes from the expectations that the Tricolor will fall short of, just as the national mythology that glorifies the Revolution as an equalizing force has never fully delivered on its promises, so too the Tricolor flatter to deceive. In other words, just like the nation itself, Mexican soccer offers perpetual promise and unfulfilled potential.

* If Mexico loses there is still a slight chance that it could qualify for the intercontinental playoff, but it would be highly unlikely. It would need to defeat Costa Rica in Costa Rica and overtake either Panama or Honduras (or both) on goal differential.

** I admit to being a huge Pablo Barrera fan. Though he has not featured regularly in the national set-up since a knee injury in 2012, and is never the flashiest of players, he has a certain intangible quality and toughness that Mexico has lacked of late. Moreover, the team plays better when he is on the field. Since 2009 in games that matter (tournaments and qualifiers) with Barrera on the pitch: 14-1-2. In 2013 with Pablo: 1-0-1; without: 0-4-2.

1. Manuel Seyde, in Greco Sotelo, Crónicas del fútbol mexicano, volumen 3: El oficio de las canchas (1950-1970), (Mexico City: Editorial Clio, 1998), 14; and Ramón Márquez C., “Introducción,” in Carlos Calderón Cardoso, Crónicas del fútbol mexicano: Por amor de la camiseta, volumen 2 (1933-1950), (Mexico City: Editorial Clio, 1998), 10.

2. There is some debate about the tour. RSSSF, the statistical database for soccer, shows that the tour took place in early January 1923 and that Mexico lost one game 3-1. Galindo and Hernández, however, claim that the tour occurred in December 1922, and that Mexico won two games and tied one. See Galindo and Hernández, 49; and http://www.rsssf.com/tablesm/mex-intres.html. On the 1930 World Cup, see Galindo and Hernández, 65-66.

3. Eric Zolov, “Showcasing the ‘Land of Tomorrow’: Mexico and the 1968 Olympics,” The Americas 61:2 (October 2004), 163. See also Keith Brewster and Claire Brewster, “Cleaning the Cage: Mexico City’s Preparations for the Olympic Games,” The International Journal for the History of Sport 26:6 (April 2009), 790-813; and Kevin B. Witherspoon, Before the Eyes of the World: Mexico and the 1968 Olympic Games (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2008).

4. “Los Cachirules: Escándalos Deportivos,” Televisa Deportes, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=so1gW3LuClg, accessed December 20, 2011; Leon Krauze, Crónicas del fútbol mexicano (volumen 5): Moneda en el aire (1986-1998), (Mexico City: Editorial Clio, 1998), 28-29; “Caso ‘cachirules’: negro recuerdo,” El Universal (April 20, 2008), http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/deportes/99513.html, accessed December 20, 2011.

5. Roger Magazine, Golden and Blue Like My Heart: Masculinity, Youth, and Power Among Soccer Fans in Mexico City, (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007), 17.

October 8, 2013

Qatar 2022 could be FIFA’s biggest mistake ever

[image error]

Growing up around an Egyptian father–absolutely obsessed with football–there were certain truths that I had to accept and never question:

1. Pele is the greatest soccer player of all time, and any Argentinian fan who disagrees is blinded by bias.

2. Never trust a fan of the Algerian national team.

3. Never be optimistic about the English national team.

4. Never trust FIFA because it is the most corrupt governing institution in the world.

With the 2022 World Cup eight short years away, FIFA President, Sepp Blatter, arguably the most nefarious man in sports, has dug himself into an inescapable hole by picking Qatar to host the world’s largest sporting spectacle. On December 2, 2010, Blatter, a well-rounded (and I mean well-ROUNDED), middle-aged Swiss man, waddled onstage in Zurich, Switzerland and announced, with his slimy little DeNiro-esque smile, that the 2018 and 2022 World Cups would be in Russia and Qatar, respectively.

Utter shock swept the world regarding Blatter’s announcement. After being courted by Prince William, David Beckham, Morgan Freeman, and Bill Clinton to name a few, Blatter and FIFA’s 24-man selection committee chose the “riskiest” potential host nations, according to FIFA’s own inspection team.

In Qatar, the simple yet effectively untouchable problem is the heat.

It does not take a weather man to understand that Qatar is one of the hottest countries in the world. But in case there are disbelievers out there: Qatar averages 100 degrees Fahrenheit six months of the year, and moreover tends to regularly exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer months. The FIFA Inspection team reported to the selection committee a “potential health risk for players, officials, the FIFA family and spectators,” if the World Cup were held in Qatar. And who can blame them? The country is a human hotbox. There is a reason that more people live in Montana than live in Qatar.

Despite these very real dangers, Blatter and FIFA still chose Qatar. One of many explanations for the decision lies in the fact that many prominent FIFA personalities may benefit from lucrative economic interests in the Middle Eastern country. In an interview with German magazine, Die Zeit, Blatter rather candidly admitted that “European leaders recommended to their voting members to vote for Qatar, because they have economic interests with this country.” Two of the big names rumored to have heavily pushed for Qatar for this reason are former French president Nicolas Sarkozy and UEFA president, and former French national star, Michel Platini. Furthermore, in October 2010, reporters from the Sunday Times posed as American lobbyists and secretly videotaped two ex-selection committee members demanding “hundreds of thousands of dollars for their votes.” All of this seems a little fishy to me.

[image error]

Now, with the eyes of FIFA and the rest of the sporting world fixated on the potentially miserable Qatar World Cup, slimy Sepp keeps trying to push for change to a Winter World Cup–a divergence from tradition that would not only enrage soccer Puritans around the world, but also postpone major league play for 1-2 months. A hiatus like this is even less likely than Scotland winning a World Cup. In other words, it is very, very, very highly unlikely.

However, FIFA, corruption aside, cannot stand idly by and let players and fans die from heat exhaustion at a summer World Cup in Qatar. Such a situation would diminish FIFA’s legitimacy and could potentially bring about the end modern-day FIFA.

On top of the problems with the Qatar World Cup, stories are now surfacing about Qatar bringing Nepalese immigrants to build the stadiums–effectively indentured servants. To make matters worse, hundreds of these servants have already died due to heat exhaustion and unfair working conditions, thus raising global awareness of potential for danger in a Qatar World Cup. In recent weeks, worldwide uproar has broken out over these blatant human rights violations, violations persisting under FIFA’s so-called “philanthropic” nose.

In my opinion, the only solution to this predicament is to uproot the 2022 World Cup, relocating it to one of the more qualified original bidders, like the US or England. With the high stadia count and abounding infrastructure in these two countries–not to mention their substantially superior labor conditions–would it be inconceivable for one of them to muster up a short-notice World Cup? Although it would not be ideal, what other options do Blatter and FIFA have?

Whatever is done about this World Cup, one thing is for sure: Qatar 2022 will go down as one of the biggest mistakes ever made in, not only the history of FIFA, but also the history of global soccer altogether.

An Uneven Playing Field

I’ve lived in the United States for over ten years now, and yet somehow I still struggle to remember the name of my hometown’s American football team (give me a sec… oh that’s right, Atlanta Falcons – Rise up!). Being a Greek South African (born in SA, but 100% of Greek descent), my sports upbringing was dominated primarily by soccer (with rugby and basketball coming in close second). However, the stop-and-go pace of American football as compared to the rhythmic flow of “the beautiful game” has always deterred me from ever watching more than one full quarter of a game. I’d be lying if I told you I knew which NFL team won the most recent Super Bowl or who the best quarterback in the league is right now. In fact I’d be lying if I told you I even cared. But there is one thing that I do envy about American football (the NFL in particular), and that’s the fact that, unlike most European soccer leagues, it embraces an even playing field.

I’m a huge fan of the underdog. Ask me which team I want to win in a match and (unless it involves my beloved Olympiakos) I’m almost always rooting for the non-favored team. Perhaps it stems from being both the only daughter and youngest child in a loud, obnoxious Greek family, but there’s something about an unforeseen victory by an underrated opponent that gives me the utmost satisfaction. With all this being said, those of us who are avid European soccer fans know that the chances of an underdog team ever winning a domestic league championship are slim to none.

If we take a look at the champions of both La Liga and the English Premier League since the start of the 21st century, we see both leagues are dominated by less than a handful of teams. Since 2000, Real Madrid and Barcelona have been the two most undoubtedly successful teams in La Liga (with the rare occurrence of Valencia breaking through El Clasico barrier). Real and Barça have won 32 and 22 titles, respectively, since the establishment of La Liga in 19291. In fact, no other club has won the title on more than nine occasions1. In the EPL, a similar trend can be seen, although it is not quite as strong or as historically rooted.

However, if we take a look at the winners of the Super Bowl over the same time frame, we see a trend that falls on the total opposite end of the spectrum. In the last decade, 9 different teams have won the Super Bowl.

What constitutes for this stark difference in playing fields? In essence, it is the drastically different economies of the NFL and European soccer. The NFL consistently rewards mediocre franchises with the most talented young prospects through a reverse-order draft2. Any team from any city has the same opportunity to compete, and in order to ensure this, the NFL has created a variety of mechanisms to prevent a free market for talent2. For example, player movement and salaries are severely restricted: a rookie draft denies young players the opportunity to have teams bid for their services, a salary cap prohibits teams from spending over a certain amount of money on players, and a franchise tag forces teams to give up two first-round picks to sign each other’s most coveted free agents2.

On the other hand, the nonrestrictive structure of La Liga allows clubs like Barça and Real to financially operate on a higher level and thus make deals that other clubs could only dream of acquiring. Who could forget this year’s transfer of Gareth Bale to Real Madrid for £85.3million, making him the most expensive transfer to date3. The fee eclipsed the £80million that Real paid in 2009 for Cristiano Ronaldo, the second most expensive transfer in the league, but still the highest paid player, making approximately $20.5 million a year, while Barça’s star Lionel Messi comes in close behind with an annual salary of around $20 million4.

Basically, there are no limits to how Barcelona and Real Madrid can acquire talent. However, since they have the best players, they also have the most fans. With more fans comes more money, and with more money, they can afford to buy the best players. It’s a never-ending cycle that gives way to an uneven playing field, but we can’t deny that it generates some incredible soccer.

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_...

2. http://www.policymic.com/articles/208...

3. http://www.mirror.co.uk/all-about/gar...

When Football Modeled Democracy: Socrates in Brazil

This short documentary film (narrated by an inimitable, bearded, Eric Cantona) tells the story of Socrates, a Brazilian footballer who along with his teammates turned a football team, Corinthians, into a space for democratic practice and ultimately contestation against the dictatorship in Brazil. The film is part of a larger series co-produced by Al Jazeera and Arte called “Rebelles du Foot,” “The Rebels of Football.” It includes another film on Rachid Mekloufi and the role of football in the struggle for Algerian independence, nicely reviewed here by Shireen Ahmed at the blog A Football Report.

Enjoy the film and share your thoughts here!

The Europa League a complete waste of time?

What exactly is the Europa League? It’s a second tier competition meant for those “losers” that miss out of competing in the Champions league. It means less T.V revenues, it means playing on a Thursday night (less recovery for league fixtures) and it means that you have to have two full squads in order to keep up with the competition. The Europa League has two extra legs in comparison to the Champions league and the overall prize money for the winner is only 5 million euros compared to 35 million for just qualifying into the Champions league.

The key issue to me seems to be the lay over time between European matches and league matches. Ultimately, if you do not win league matches you do not get into the champions league, however, the way the system works, coefficients for champions league victories are practically the same for Europa league victories, meaning teams of leagues that focus on their domestic league such as Italy, get slaughtered to leagues such as Germany.

Italy has lost its additional champions league spot over the past two years for this exact reason. While Italian clubs have done better in the Champions League than the Germans, the Germans nonetheless, consistently have three teams in the late stage of the Europa league, so the question remains is it more important to have the strongest teams in Europe (e.g In 2009-10, German clubs outscored Italian clubs by 2.6 coefficient points even though Internazionale won the competition, a huge margin[1])? Or do we want to see well-rounded leagues?

Personally, I see a well rounded league as fiscally impossible, while we can have a stronger competition towards the top in leagues like the Portuguese Superliga, La Liga and Ligue 1, it seems pretty much impossible that six or seven teams could be challenging for a league title, except in a fiscally uneven playing field like England.

The main issue here is that many leagues feel very differently about the Europa league, as it offers no economic incentive. The Dutch, the Russians and the Italians are key example of this. Italians feel there is a sense of injustice, and it stems from the methodology of the coefficient. Germany, the argument goes, has only overtaken Italy by its strong performance in the Europa League, a competition that has traditionally been taken less seriously in Italy due to economic benefit. It is argued that teams such as Udinese, cannot afford to give it there all in the Europa league as ultimately there league performance outweighs the importance of Europa. It might be time for Michel Platini to sit down and reform the competition as a whole.

[1] http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2011/writers/raphael_honigstein/03/02/bundesliga-serie-a/index.html#ixzz2gIoS8yNG

October 7, 2013

François Hollande, des impôts et leurs conséquences pour le foot français

Dans sa campagne pour le président, François Hollande a introduit un impôt qui taxe des millionnaires à un tarif de soixante-quinze pourcent. Cette loi controversée a encouragé beaucoup de français riches à déménager aux autres pays européens, comme l’acteur Gérard Depardieu.

En ce qui concerne le football, ces impôts sont très importants. En avril 2013, le gouvernement a dit que des équipes du football françaises deviendraient soumis aux impôts. Ces nouveaux impôts inhibent des équipes françaises parce qu’elles doivent payer des impôts plus hauts que des autres équipes européennes. Par conséquent, des équipes françaises ne peuvent pas attirer le talent parce qu’elles ne peuvent pas payer leurs joueurs comme les autres équipes.

Cette situation est très intéressante pour la France parce qu’elle juxtapose deux choses que les Français adorent : l’égalité et le football. Le socialisme de François Hollande ont obtenu le soutien de la majorité comme l’écart socio-économique entre les riches et les pauvres continuent à élargir. Cependant, l’exode des riches de la France est un grand problème pour l’économie et la croissance. Le football, le sport le plus populaire dans la France, est aussi important aux Français. Les supporters n’aiment pas que leurs équipes soient défavorisées parce que des équipes françaises représentent leurs villes et leur pays. L’impôt coûtera 82 millions au foot français et mille salariés seraient concernés en France. Le président du Ligue de Football Professionel (LFP), Frederic Thiriez a dit que l’impôt serait “la mort du football en France.”

Nous verrons si le football gagne dans cette situation!

Laurent Dubois's Blog

- Laurent Dubois's profile

- 44 followers