Chris Cleave's Blog: Human Again with Dr Chris Cleave, page 3

October 2, 2015

Darkness and the gloomy shade of death

A lovely, moody set for Sir Trevor Nunn’s epic staging of Henry VI at Kingston’s Rose Theatre last night. Shakespeare’s story of the tender Henry’s doomed reign is less of an arc than an unravelling, and Nunn plays it out to the desperate end in this fitting darkness that seems to become darker still.

Nunn is a generous director, badging Lancaster and York in their home colours in England and their away kit in France, and otherwise using all kinds of ingenious devices to make life easy for theatregoers such as this one – who might otherwise struggle to follow treacheries within treacheries. Right from the start this production is on your side, beginning with the reading aloud of the late Henry V’s will: an elegant idea that sets the scene and establishes the principals with efficiency and style.

Three parts of the sixth Henry make for a lot of material, pulled from a congested section of England’s timeline. Throughout the play Nunn’s style is to abridge without condescension, and to use the space this creates to pick out a few breathtaking moments from the chaos and invest them with an enormous emotional punch.

Brilliantly done is Mortimer’s drawn-out death from old age as he reveals to Richard Plantagenet his claim to England’s throne. So precisely does Nunn calibrate this momentous event, and with such clinical realism does Geoff Leesley play Mortimer’s death agonies, that the production immediately reaches that Shakespearean nexus: the highest statecraft meets the visceral, dirty, rattling last breaths of we mortal worms. The hairs were up on everyone’s arms. It felt that death was in the room with us.

Shakespeare sets out his stall early on: Henry VI is all about the dying. The comic turns of Joan and her dubious virginity; the pathos of poor helpless Henry (the excellent Alex Waldmann eliciting laughter and tears by turns); even the passion of Margaret and Suffolk – these are smooth stones skipping across the surface of a very deep lake of death. We know that they must soon sink, and we see how quickly we will follow.

The saddest death is Talbot’s, and on the page it rather comes across as Shakespeare phoning it in:

Come, come and lay him in his father’s arms:

My spirit can no longer bear these harms.

Soldiers, adieu! I have what I would have,

Now my old arms are young John Talbot’s grave.

Nunn give dignity to this dying and makes it the fulcrum of his play with an exquisitely tender performance from James Simmons – who is, up until the moment, utterly convincing as the athletic, indestructible, lionhearted Talbot. England’s selfless servant has been hung out to dry by the feuding Somerset and York. After all the divine auguring and the clash of kingdoms, Talbot’s death is small, personal and incredibly moving as he cradles his dead son in his arms. Up until now, perhaps the play let in some light. From now on, we expect the arrival of night.

It is often effective, and not necessarily wrong, to bring Shakespeare literally up-to-date on stage and screen. Nunn eschews it in this production, which he resolutely leaves where Shakespeare put it. He does honour to the audience by choosing the play and then allowing it to talk for itself. That the political machinations speak to our own time is evident. That death holds court after all is the awful, timeless joke.

Perhaps Nunn allows himself just one, incisive, contemporary reference in the brutal decapitation of Suffolk in the play’s finale. Suffolk’s murder by the mob, and the nastily accurate fast-twitch of his legs as the knife saws into his neck, call to mind the cruel videos and the unutterable fear of our age: of a centre that is failing to hold.

Henry VI is the first instalment of a Wars of The Roses trilogy (with Edward IV and Richard III) on at the Rose Theatre in Kingston (London, UK) until 31st October. I don’t have a connection with the theatre or the production. (I review books & theatre because as E.M. Forster put it, I don’t know what I think until I see what I say. I only publish reviews of things I enjoyed.)

September 29, 2015

Pre-ordering EVERYONE BRAVE IS FORGIVEN

(If you do read my new book: thank you, very much.)

UK & Ireland

Hive (independent booksellers)

Hive (independent booksellers)

USA

Indie Bound (independent booksellers)

Indie Bound (independent booksellers)

Australia

Canada

If you’d like your bookstore listed on this page, I’d be delighted to do so. Please let me know on Twitter @chriscleave or leave a message in the comments below – thanks!

(I’m especially keen to find a bookseller taking pre-orders in NZ)

February 26, 2015

Chris Cleave: royalty-free author photos

You are very welcome to use these images free of charge online or in promotional materials for events – but please remember to include the photographer’s by-line. Thank you.

author CHRIS CLEAVE

author CHRIS CLEAVEpic James Emmett

author CHRIS CLEAVE

author CHRIS CLEAVEpic James Emmett

author CHRIS CLEAVE

author CHRIS CLEAVEpic James Emmett

author CHRIS CLEAVE

author CHRIS CLEAVEpic James Emmett

author Chris Cleave

author Chris Cleave pic LOU ABERCROMBIE

author Chris Cleave

author Chris Cleave pic LOU ABERCROMBIE

author Chris Cleave

author Chris Cleave pic LOU ABERCROMBIE

Tweet

January 28, 2015

Thurber

January 26, 2015

Back online

I’m sorry this site has been offline – it was hacked and I’m currently putting it back together again. Normal service will resume shortly, I hope. In the meantime, apologies to everyone whose comments were lost – I will try to restore them. Thanks – Chris

April 29, 2014

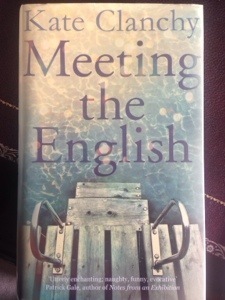

‘Meeting the English’ by Kate Clanchy

This was the fifth book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize – I’m chairing the judges this year – and I enjoyed it hugely.

This was the fifth book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize – I’m chairing the judges this year – and I enjoyed it hugely.

The compassionate and capable 17-year-old Struan Robertson travels to Hampstead from his bleak Lowland town in answer to an advertisement placed by the family of Philip Prys, a literary behemoth and incorrigible philanderer now laid low by a stroke. The family need a nurse for Philip, but it soon becomes clear that Struan’s presence will be a boon to them all.

This is a novel that begins as an enjoyable hatchet job on a certain kind of superannuated literary grandee, and develops into something altogether more thoughtful and moving. Prys’ family, ripped apart by his self-indulgence and their own hardness, have lost the ability to love one another or even to be civil. Struan, having not yet developed the Southerner’s immunity to empathy, becomes a healing influence – but at an increasing cost to himself.

It is a mark of this novel’s strength that it works on several levels at once. On the surface it is a satire that flashes with neat insights and wicked humour. (The author’s summary dispatching of Virginia Woolf’s THE WAVES alone is worth the price of admission, and the sheer viciousness of Myfanwy, Prys’ awful ex, is addictive).

At the same time, this is a book that has a beating heart in the tenderness with which the author draws the character of Juliet, the 16-year-old daughter of Myfanwy and Prys. Poor Juliet – rather plain, rather plump and rather confused – has never been loved or wanted, but there is something bright in her nature that refuses to be rolled over.

‘I’m not shagging anyone, and probably I never will, and anyway, I’m probably a lesbian, I keep thinking about Celia’s hips.’ And Juliet collapsed on the filthy bed, and sobbed… Myfanwy sat down beside her.

‘You can’t,’ she said very certainly, ‘be a lesbian, Juliet.’

‘Why the fuck not?’ asked Juliet.

‘Because,’ said Myfanwy, ‘you’re too fat. You can’t be a fat lesbian, see, because people will just think that’s why you are one. Because you can’t get a man, you see. Lesbians don’t want lesbians like that.’

At the centre of this novel is Prys himself, crocked and helpless, sentient but speechless, sometimes aware of his predicament and at other times believing himself to be watching an arthouse film, or even writing the dialogue as it issues from the mouths of his family. These scenes are beautifully done, and the author wears lightly what is clearly a gift of wisdom and an enormous amount of research.

I was struck by what an extraordinarily accomplished piece of writing this is. From the first chapter, one can relax in the certainty that the author knows exactly what she is doing and where she is going. It’s masterful. In common with several of the books on the long list, the performance is so assured that there is nothing to suggest a fictional debut.

I basked in the glow of this book and felt privileged to have met it.

‘Meeting the English’ by Kate Clanchy

This was the fifth book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize – I’m chairing the judges this year – and I enjoyed it hugely.

The compassionate and capable 17-year-old Struan Robertson travels to Hampstead from his bleak Lowland town in answer to an advertisement placed by the family of Philip Prys, a literary behemoth and incorrigible philanderer now laid low by a stroke. The family need a nurse for Philip, but it soon becomes clear that Struan’s presence will be a boon to them all.

This is a novel that begins as an enjoyable hatchet job on a certain kind of superannuated literary grandee, and develops into something altogether more thoughtful and moving. Prys’ family, ripped apart by his self-indulgence and their own hardness, have lost the ability to love one another or even to be civil. Struan, having not yet developed the Southerner’s immunity to empathy, becomes a healing influence – but at an increasing cost to himself.

It is a mark of this novel’s strength that it works on several levels at once. On the surface it is a satire that flashes with neat insights and wicked humour. (The author’s summary dispatching of Virginia Woolf’s THE WAVES alone is worth the price of admission, and the sheer viciousness of Myfanwy, Prys’ awful ex, is addictive).

At the same time, this is a book that has a beating heart in the tenderness with which the author draws the character of Juliet, the 16-year-old daughter of Myfanwy and Prys. Poor Juliet – rather plain, rather plump and rather confused – has never been loved or wanted, but there is something bright in her nature that refuses to be rolled over.

‘I’m not shagging anyone, and probably I never will, and anyway, I’m probably a lesbian, I keep thinking about Celia’s hips.’ And Juliet collapsed on the filthy bed, and sobbed… Myfanwy sat down beside her.

‘You can’t,’ she said very certainly, ‘be a lesbian, Juliet.’

‘Why the fuck not?’ asked Juliet.

‘Because,’ said Myfanwy, ‘you’re too fat. You can’t be a fat lesbian, see, because people will just think that’s why you are one. Because you can’t get a man, you see. Lesbians don’t want lesbians like that.’

At the centre of this novel is Prys himself, crocked and helpless, sentient but speechless, sometimes aware of his predicament and at other times believing himself to be watching an arthouse film, or even writing the dialogue as it issues from the mouths of his family. These scenes are beautifully done, and the author wears lightly what is clearly a gift of wisdom and an enormous amount of research.

I was struck by what an extraordinarily accomplished piece of writing this is. From the first chapter, one can relax in the certainty that the author knows exactly what she is doing and where she is going. It’s masterful. In common with several of the books on the long list, the performance is so assured that there is nothing to suggest a fictional debut.

I basked in the glow of this book and felt privileged to have met it.

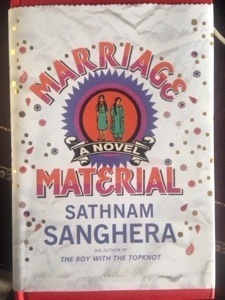

‘Marriage Material’ by Sathnam Sanghera

This was the fourth book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize – I’m chairing the judges this year – and I couldn’t get enough of this clever, funny and enlightening novel.

This was the fourth book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize – I’m chairing the judges this year – and I couldn’t get enough of this clever, funny and enlightening novel.

When Arjan’s father dies, he leaves his bohemian London milieu to help his mother run the family’s convenience store in Wolverhampton. What begins as a few days’ visit turns into a full-blown crisis of identity that sees Arjan strung out between his Punjabi roots and his London life, as embodied in the relationship with his longsuffering fiancée, Freya.

The author bills the novel as a subcontinental “remix” of Bennett’s ‘The Old Wives’ Tale’, compete with a family of shopkeeping Bainses, a constant Kamaljit who plays the dutiful daughter, and a sophisticated Surinder who elopes with a bagman. It all works brilliantly because – although slyly satirical – the satire is of the warm hearted and fun loving stripe and – although knowing – the book is unpretentious and fabulously written.

Sanghera is incapable of writing a sentence that isn’t funny on some level. Sometimes he’s quietly amusing, sometimes obliquely, sometimes poignantly. And then every now and then he drops in a laugh-out-loud line that has the reader in bits. I think if you like Howard Jacobson’s style then you’ll enjoy Sanghera’s writing.

“I could only recall one other instance of racist graffiti, when I was about seven and someone had scrawled a massive ‘KKK’ on to our house door. I remember asking Dad what the letters meant and him replying that they must be the initials of the miscreant in question. I eyed a classmate at my infants school going by the name of Kuljit Kaur Kalirai with suspicion for months afterwards.”

This is a book that continues to delight. From its wonderful opening meditation on life behind the counter of a corner shop, it grows into a moving examination of filial and cultural ties before taking a mischievous diversion through the hilarious patois of Arjan’s foil, Ranjit, and then racing towards its tongue-in-cheek farce of a finale.

On a literary level I was impressed at the audacity of conjoining a modern theme with Bennett’s plot, and struck by its appropriateness in a novel concerned with the marriage of cultures. But the book certainly doesn’t presuppose familiarity with Bennett’s novel, and works neatly as a stand-alone piece – which was really the level on which I enjoyed it most.

The novel has stayed with me since I finished it a few days ago, and I’ve been trying to work out why. I think it’s because the novel has some sharp and timely truths hidden in the folds of its lighthearted tale. This is a timely and meaningful story about the tug of cultures, told in an engaging and uncondescending way. I think it might be the kind of thing Oscar Wilde had in mind when he said: If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they’ll kill you.

‘Marriage Material’ by Sathnam Sanghera

This was the fourth book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize – I’m chairing the judges this year – and I couldn’t get enough of this clever, funny and enlightening novel.

When Arjan’s father dies, he leaves his bohemian London milieu to help his mother run the family’s convenience store in Wolverhampton. What begins as a few days’ visit turns into a full-blown crisis of identity that sees Arjan strung out between his Punjabi roots and his London life, as embodied in the relationship with his longsuffering fiancée, Freya.

The author bills the novel as a subcontinental “remix” of Bennett’s ‘The Old Wives’ Tale’, compete with a family of shopkeeping Bainses, a constant Kamaljit who plays the dutiful daughter, and a sophisticated Surinder who elopes with a bagman. It all works brilliantly because – although slyly satirical – the satire is of the warm hearted and fun loving stripe and – although knowing – the book is unpretentious and fabulously written.

Sanghera is incapable of writing a sentence that isn’t funny on some level. Sometimes he’s quietly amusing, sometimes obliquely, sometimes poignantly. And then every now and then he drops in a laugh-out-loud line that has the reader in bits. I think if you like Howard Jacobson’s style then you’ll enjoy Sanghera’s writing.

“I could only recall one other instance of racist graffiti, when I was about seven and someone had scrawled a massive ‘KKK’ on to our house door. I remember asking Dad what the letters meant and him replying that they must be the initials of the miscreant in question. I eyed a classmate at my infants school going by the name of Kuljit Kaur Kalirai with suspicion for months afterwards.”

This is a book that continues to delight. From its wonderful opening meditation on life behind the counter of a corner shop, it grows into a moving examination of filial and cultural ties before taking a mischievous diversion through the hilarious patois of Arjan’s foil, Ranjit, and then racing towards its tongue-in-cheek farce of a finale.

On a literary level I was impressed at the audacity of conjoining a modern theme with Bennett’s plot, and struck by its appropriateness in a novel concerned with the marriage of cultures. But the book certainly doesn’t presuppose familiarity with Bennett’s novel, and works neatly as a stand-alone piece – which was really the level on which I enjoyed it most.

The novel has stayed with me since I finished it a few days ago, and I’ve been trying to work out why. I think it’s because the novel has some sharp and timely truths hidden in the folds of its lighthearted tale. This is a timely and meaningful story about the tug of cultures, told in an engaging and uncondescending way. I think it might be the kind of thing Oscar Wilde had in mind when he said: If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they’ll kill you.

April 24, 2014

Sedition by Katharine Grant

This was the third book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize. (I’m chairing the judges this year). What an eclectic and intriguing list it is proving to be.

This was the third book I read from the long list for the Desmond Elliott Prize. (I’m chairing the judges this year). What an eclectic and intriguing list it is proving to be.

Set in a licentious coffee house London where cash is still king even as Europe is swept by revolution, ‘Sedition’ is one of the most delightfully contrary novels I have met.

The book is a period piece rich with historical detail, yet its dialogue and themes are resolutely modern. It is a light-hearted comedy of arriviste parental aspirations versus breathless teenage deflowerings, but the comic flow works against a counter current of convincing darkness. The novel repeatedly flirts with the erotic but coolly pulls focus. It is built on high musical metaphors, yet it isn’t above deploying the lowest euphemisms: this is a novel where, during a very technical variation on Bach, a man might contemplate whether he will go in by the servant’s entrance.

This, then, is a tease of a novel. It continually offers one thing only to snatch it away and replace it with something quite else – and it does this again and again, right through to an ending that is a clever – because fitting – anti-climax.

I will confess to being buffeted by this novel as if by squally winds. Just when I thought I had its number, the author took the already disturbing relationship between the novel’s femme fatale, Alathea, and her father to an altogether more serious place. There is a disturbing and unquiet beast hiding in the heart of this heavily-veiled novel. The author never completely reveals the novel or its characters, and the effect, at least on me, was unexpected.

In keeping with the novel’s paradoxical qualities, I always adored the plot and occasionally deplored the style. I found myself irritated enough to throw the book at the wall several times, but then intrigued enough to read the whole thing twice.

It was startling to realise that something so contrary to one’s taste can be very much to one’s liking. I finally admit to finding the book extremely impressive.

What won me over was the sheer strength of the story, which has the legs to escape the bounds of the novel. I could not help visualising ‘Sedition’ as a multi-part TV production, complete with a burlesque cast of debutantes both vampish and ingénue, a flawed Cassanova scheming to defile them one per episode, a high-contrast aesthetic of beauty, ugliness and deformity, a fetid and lusty London for a backdrop, a hundred exquisite costumes, and a ready-made soundtrack by J.S. Bach.

This is a wonderful read from a born storyteller.

Human Again with Dr Chris Cleave

- Chris Cleave's profile

- 3305 followers