Lou Schuler's Blog, page 2

October 17, 2012

The Science of Muscle Growth

I’ve never actually met Brad Schoenfeld in person. But I’ve come to rely on his work. When you read The New Rules of Lifting Supercharged, you’ll see exactly what I mean. He’s codified the muscle-building process in a way that’s both simple and fantastically complex. If nothing else, my vocabulary gets bigger every time I read one of his studies.

Now he has a new book out, called MAX Muscle Plan.

It starts with the information from his studies, and then provides months’ worth of somewhat hardcore workouts, based on his 20+ years as a trainer, during which, he estimates, he worked one-on-one with more than 1,000 people. The range of clients and athletes is breathtaking: Aside from the typical men and women you’d expect to see with a trainer in a gym, he’s been employed by everyone from pro athletes (he’s worked with the New York Knicks and Rangers, along with pro tennis players) to figure competitors and bodybuilders (a sport in which he competed for some 10 years in the eighties and nineties) to nonagenarians.

These days much of his time is devoted to academic work. He’s finishing his Ph.D. at Rocky Mountain University while also teaching exercise science at Lehman College in the Bronx. He fills out his schedule with writing, speaking, and consulting with a select group of elite athletes, mainly physique competitors.

He took time out from his busy schedule — which, frankly, makes mine look I’m semi-retired — to answer a few questions about his work.

Brad, thanks to your studies, in the past two years I’ve probably learned more about what makes muscles grow than I did in the previous 10. I referred to your work early and often in Supercharged. So let me start by asking you this: What have you learned recently that even you didn’t know? What did you find that surprised you?

I think what surprised me most is the lack of research on trained individuals. The vast majority of studies use untrained or “recreationally trained” subjects – who, by all accounts, are in roughly the same boat as untrained subjects.

Why is that an issue?

Well-trained individuals respond differently to intense training than those just starting out. You can’t really extrapolate their results to those with training experience. I’ve made this topic a focus of my doctoral research. I hope to have some data very soon.

Your work has given me a simple way to explain what we do in the gym. We’re trying to 1) generate muscular tension, 2) induce some level of muscle damage, and 3) create metabolic stress. But there’s no question which of those three is most important, right?

Well, mechanical tension is the dominant factor in muscular hypertrophy, to a degree. Without it, there simply isn’t a reason for muscles to adapt and grow.

That said, there’s compelling evidence that a threshold exists, although it’s not clear what the exact threshold is. Once you get beyond it, other factors can be extremely important in the process.

There’s some speculation that, to get a meaningful growth response, you need an intensity of at least 60 percent of your one-rep max. But now some research has challenged this idea.

Based on what we know from research, along with my many years as a trainer and competitor, I believe there’s a “sweet spot” where all these factors can be optimized for muscle development. It certainly makes me think there’s a benefit to training in a variety of rep ranges.

“Muscle damage” is a tricky one to explain. A lot of people avoid training as hard as they should because they’re afraid of the pain. Meanwhile, meatheads like us learn to trust post-workout soreness. We see it as proof that we gave our muscles a new growth stimulus. But what’s the actual connection between muscle damage and soreness? Is soreness a requirement for muscle growth?

It’s a great question. It would take an entire textbook chapter to fully explain the complexities. But for brevity, let’s just say there’s compelling evidence that some muscle damage is “good,” in the sense that it promotes remodeling of muscle tissue, where the muscle ends up stronger than it was before. [If you're not into that whole brevity thing, you can check out Brad's study on muscle damage.]

On the other hand, too much damage impairs remodeling and limits your ability to train. Think of it like getting a suntan: If you stay within the capacity for your skin to adapt, you’ll get a nice tan. If you overdo it, you burn.

Mild soreness probably indicates you’ve set the stage for growth. But a lack of soreness doesn’t necessarily mean you haven’t. Bottom line: Don’t use soreness as a definitive gauge of a good workout.

You’ve worked hard to create a bridge from science to practice. Tell me some of the things that traditional bodybuilding had right all along.

Bodybuilders get trashed a lot for unscientific training — and sometimes rightly so — but we now know that many of the underlying principles are perfectly valid.

For instance, bodybuilders talk about “training for the pump.” We used to say this was just temporary and cosmetic. But now research is showing that the cell swelling responsible for the pump may actually promote muscle growth.

That doesn’t mean that you should train solely for the pump. As I said a minute ago, you really need the full spectrum of rep ranges. But there is a benefit to the pump beyond what you see in the mirror five minutes later

Bodybuilders also realized, intuitively, the importance of variety. Free weights, machines, and cables all have certain advantages and disadvantages when it comes to building muscle, and the disadvantages of one tend to be the advantages of the other. By combining these movements you get a synergistic effect that maximizes results.

Same with training from multiple angles. We’ve known for a long time that muscles like the delts and pecs have separate “heads.” So you can target individual areas of the given muscle. Other muscles like the trapezius have upper, middle, and lower regions that are activated by different movement patterns.

But some of the newer anatomical research shows that the majority of muscles are compartmentalized, allowing for even greater targeting than previously thought.

For instance, the long and short heads of the biceps have subdivisions that are innervated by their own branches of the primary neurons. The upshot is that elbow flexion targets one set of muscle fibers, supination [rotating your wrist outward] targets another set, and combinations of flexion and supination target fibers in between.

This is true for lots of muscles, which only emphasizes the importance of using lots of different exercises in your programs.

What’s the flip side? What are some common practices that, based on your research, don’t make much sense?

One that comes to mind is doing cardio on an empty stomach to maximize fat loss. Fat burning needs to be evaluated over days. You can’t just look at how much fat you burn during the activity itself. Your body is very adept at adjusting how it uses fat for energy. The intensity of the cardio helps determine how much fat you use post-exercise.

So even if you want to argue that you might burn a few more fat calories during fasted cardio – and I have to say, the evidence doesn’t really support the idea – the overall effect on body composition is nil. [Brad wrote a review on fasted cardio for the NSCA's Strength and Conditioning Journal.]

I’ll also say that, while bodybuilders have gotten the concept of variety right in principle, what they do in practice doesn’t always make sense. For example, there’s no evidence that concentration curls give your biceps a better “peak.” Nor will chest flies build your “inner” chest. And leg extensions don’t target the vastus medialis at the exclusion of the other quad muscles. I could go on and on.

Another biggie: the idea that training with high reps gets you “cut.” I actually had a student — an aspiring bodybuilder — insist that this was the case. I tried to explain the physiology to him, and when that didn’t work I gave up and said if he could produce one peer-reviewed study to support his opinion, I’d give him an A for the semester and he wouldn’t have to come to class anymore. Suffice to say, he’s still in class.

Let’s talk about your book. The workouts in MMP are challenging, to put it mildly. In your entry-level workouts, you have beginners doing squats and deadlifts three times a week. What’s the rationale behind that?

There’s actually a break-in phase for novice lifters. It’s a more general total-body routine to develop coordination and build a base of strength and size. If you’re new to lifting, I recommend doing the break-in workouts for up to six months before you jump into the MMP routine.

The phase that you’re referring to is the strength cycle, which comes right before hypertrophy training. You need those heavy, structurally based exercises like squats and deadlifts. I have regular unloading periods integrated into all the cycles to promote recovery and avoid overtraining.

You have some exercises in your book that I haven’t seen since my days at Weider in the 1990s. My shoulders ached just by looking at those upright rows and pec-deck flies. Did you take injury potential into account, or do you figure readers will sort that out on their own?

To paraphrase one of my mentors, the late, great Mel Siff, there’s no such thing as a bad exercise, only bad applications. Much of the issue is in performance.

Funny you mention the upright row. I recently coauthored an article for the NSCA on the exercise with my friend and colleague, Dr. Morey Kolber, who’s one of the top shoulder researchers. Despite the claim that upright rows are bad for the shoulders, there’s nothing in the literature to support that idea. It comes down to performing the move properly — lifting from the humerus, and not allowing the elbows to go above 90 degrees. [Here’s an interview Brad did with the New York Times on the subject.]

The MMP program is extremely flexible. It has well over 100 exercises, and I specifically say that if an exercise doesn’t feel right, don’t do it. Some exercises will have more red flags than others. Machines tend to create issues. Their design doesn’t conform well to individual body types.

But I still think it’s misguided, except in rare cases, to make blanket statements about exercises being inherently good or bad. The principle of individuality applies here.

How do you train in your own workouts? If I watched you work out, would I think, “That guy trains like a bodybuilder”? Or would I see a mix of different philosophies and techniques?

I haven’t competed in a while, and my schedule is extremely hectic. So I’ve modified my training somewhat in recent years. That said, my workouts are still much like the ones in my new book.

I periodize my workouts to give me a variety of rep ranges. I also use step loading, increasing the loads each week – usually for three weeks — within a given rep range. Then I’ll have a one-week unloading phase, where I use much lighter weights. I end up with a wave-like loading pattern to get more stimulation of muscle fibers while allowing for recovery and rejuvenation.

I also periodize training volume. Volume is arguably the most important factor that drives muscle growth. The problem is, consistently high training volumes lead to overtraining. I’ve developed an approach where I systematically increase both the frequency and number of sets over the course of the training cycle. It culminates in a “shock” phase at the end.

If I do it right, I end up with the best muscle development possible.

What do you think our workouts will look like in the future? Will we be doing the same stuff you see now, or do you think lifters will incorporate newer ideas and systems? Or, put another way, what seems cutting-edge now that you think will be common practice five to 10 years from now?

I think we’ll have the ability to write programs for an individual based on his genetic makeup

One thing that really stands out in research is the huge disparity in results you see with individual subjects. Researchers report averages, but in every study you find that some people make hardly any gains, while others are extreme responders.

At some point we’ll be able to take a cheek swab, analyze factors like fiber types and hormonal output, and create a customized routine.

That day is coming, and it’s probably not too far off in the future.

On that hopeful note, I want to thank Brad for sharing his time and knowledge. I highly recommend checking out his website, where he posts lots of great information, along with his new book, MAX Muscle Plan.

September 18, 2012

Want My Job? Here’s How to Get It

In September 2004 I got an email from Nate Green, a 19-year-old kid in Montana. He told me he wanted my job. I don’t think he meant to put me out of work. (If he did, it totally didn’t happen.) He just wanted to do what I did: write about fitness and nutrition for a living.

A few years earlier I would’ve thought he was crazy. I’d stumbled into fitness magazines when I was a grad student in creative writing. I thrived mainly because it was the perfect mix of something I was pretty good at — writing and editing — and something I was passionate about: exercise and healthy living. But I won’t lie: The lack of competition helped. Nobody I worked with wrote about fitness on purpose. Most of them couldn’t wait to move on to something else.

It was the first of many emails I exchanged with Nate; we eventually worked together on a book and at T-nation, and all in all he’s done pretty well for himself. By then I understood that Nate was just one of many fitness pros who wanted to do more than train clients.

Those who didn’t have blogs wanted to launch one. Those whose blog posts found an enthusiastic audience wanted to write for websites like T-nation. Those who wrote for T-nation wanted to get into magazines like Men’s Fitness and Men’s Health. And those who contributed to those magazines wanted to know how to get a book deal.

Lots of them came to me for advice about how to move up to whatever level they hadn’t yet reached. I did the best I could, and eventually compiled my best advice into a document that I gave away to anyone who asked. “It’s free advice,” I warned, “and worth every penny.”

About a year ago Nate convinced me that it’s time to start working on a guide that wouldn’t be free. He put me together with Sean Hyson, group training director at Men’s Fitness and Muscle & Fitness magazines, and a few months later we added John Romaniello to our team.

Our product is called How to Get Published: Writing Domination in the Fitness Industry.

I cover the basics of writing: how to get started, how to get better, how to know when your work is ready for the marketplace.

Roman explains how to create a website that reflects your personality and shows the unique knowledge and skill you bring to your industry, whatever your industry might be. (We focus on fitness writing, but really, the information applies to anyone who has a message to communicate and wants to learn how to deliver it.)

Sean, who assigns and edits hundreds of articles a year, tells you what magazines like his are looking for, how to pitch ideas that will get noticed, and how to write a good article once you get the assignment.

Then I return with a step-by-step guide to publishing a book, from shaping your idea to crafting a proposal, finding an agent, making a deal, and, oh yeah, actually writing something that will appeal to your readers.

Finally, I give aspiring writers some insight into how publishing works, who works in publishing, and why success is never exactly what you think it will be. There’s always some space between what you want to provide the market and what the market wants from you.

How to Get Published: Writing Domination in the Fitness Industry is now on sale. If you’re interested in writing about fitness — or really, any topic you know well and are passionate about — I hope you’ll give it a look. It’s not free, but I’m confident it’s worth every penny.

September 5, 2012

Gym Etiquette 201

I got my first gym membership in 1980, when I was 23. It was an old-school Vic Tanny. The branch closest to my home was open to men three days a week and to women the other three days. (My memory is imperfect, but I think it was closed on Sunday.) If I wanted to train on one of the no-men-allowed days, I had to go slightly farther to a branch that had separate weight rooms for men and women.

All the things we consider to be gross violations of gym etiquette today were just standard procedure 30 years ago. Nobody brought towels to wipe up their own sweat. It would sometimes take a few minutes to find a matching pair of dumbbells; lots of people just left them on the floor. Nobody stripped weights off the barbells or the leg-press machine.

Personal hygiene was highly variable. Some guys went weeks without washing their gym clothes. When women were finally allowed in the weight room with men, some of them came in wearing neurotoxic levels of fragrance.

Common courtesy was uncommon. My favorite example was the time I asked a couple of guys if I could work in with them while they were doing incline dumbbell bench presses. They had the only pair of dumbbells at whatever weight I used back then, and they may have had the only adjustable bench. They refused. And one of them worked at the gym! (Yes, they were taking breaks in between sets.)

The first time I encountered a personal trainer, he stuck his butt into my face while training a client on the next bench. The second time I met one, he was a gym employee—a total stranger to me—who interrupted my workout to tell me I was doing something wrong. (He may have been right, but it was still a stupid way to get my attention.)

I’ve probably forgotten most of the incidents of mooks and meatheads hogging equipment, screaming and slamming weights, or singing along with the radio. The ones I remember are bad enough. To be fair, I probably committed quite a few violations of my own in those days, which I hope the victims have forgotten.

Manners for Meatheads

Fortunately, we’ve ironed most of this out over the years. A Google search for “gym etiquette” gave me 1.3 million results. The handful of articles I scanned show a few universal ideas and some that seem highly situational. (Who gets to decide how long is too long to rest between sets?)

Most of the basics don’t need to be mentioned anymore. Everyone knows to put equipment away after using it. If gyms don’t provide towels, they expect members to bring their own.

At my current gym there’s a level of courtesy that would be unimaginable at the old Vic Tanny. Along with towels, the gym provides disinfecting wipes, and some people practically scrub down equipment when they’re finished.

Still, I get the impression each of us has a personal code that not everyone shares. Some of the things that bother me don’t seem to bother anyone else. I’m certain I do things that others find annoying.

That’s why I decided to write about some of the finer points of gym etiquette, the practices that aren’t technically out of line in every circumstance, but are still guaranteed to violate someone’s sense of propriety.

1. Blocking the dumbbell rack to do curls, shrugs, and lateral raises

You may think this one is obvious—it regularly shows up on lists of gym-etiquette violations—but I’m one of the few serious lifters in my gym who doesn’t block the rack. (Then again, I hardly ever do curls, and never do shrugs or raises, so it’s not like I have many opportunities.)

To me this is as easy call, right next to not talking on a cell phone in the weight room. If you’re strong enough to lift the weight, you’re strong enough to carry it a few feet away from the rack. But lots of people don’t see it as a problem, including, as I mentioned, some of the most experienced lifters.

2. Playing music so loud I can hear it 10 feet away

I’m one of the last holdouts against iPods in the gym. I don’t care if other people use them (except for the times I’m trying to get someone’s attention and the asshole can’t hear me when I’m standing two feet away; that kind of pisses me off), but why in the world should I have to listen to it?

Sometimes I ask the person to turn it down, and typically he’s nice about it. A couple of times people seemed embarrassed, with no idea others could hear. But one time a kid actually turned his music up after I’d asked him to turn it down. I shit you not: I could hear it across the room.

So what’s the call? Is this just a grouchy-old-man thing, or should it be part of the code?

3. Making gratuitous noise

Thankfully, the screamers are gone, at least from the places I’ve trained recently. The last one I encountered was at a local Gold’s Gym in 2004. He was doing leg presses, as I recall, and seemed quite proud of himself. I never went back.

Some noise that may seem gratuitous at first isn’t really. I used to think it was rude to drop weights on the floor while deadlifting. Now I realize it’s what you’re supposed to do; the alternative is to lower a heavy weight slowly, putting your lower back at unnecessary risk.

But from time to time someone will clank dumbbells overhead on chest or shoulder presses. First of all, it’s a stupid way to train. It takes no additional effort to bring the weights together, since there’s no gravitational resistance. If anything, it takes tension off the targeted muscles. But mainly, it’s making noise for its own sake.

4. Cutting off my space

“Personal space” in a gym is always relative to how crowded it is. I think of it like a checkerboard. You don’t occupy one of the red spaces unless all the black spaces are taken.

That’s the easy part. It only gets complicated when the available black space puts you in between a lifter and the mirror. Normally, if she’s there first, she has dibs on all the space between her and the mirror. But sometimes there’s no choice. I think we all agree on that.

The warm-up area is more complicated, especially for those of us who do mobility drills like the ones Alwyn prescribes in the NROL books. I understand that people can’t read my mind. Unless they’re watching closely, they don’t know how much room I need to the front or side. And if the area’s crowded, of course I don’t expect people to give me more room than anyone else gets.

What frustrates me is the person who has a favorite spot and is going to use it even if it’s six inches from my clipboard and towel.

It’s easy enough for me to move over. The question is what defines an open space. At a driving range or bowling alley it’s easy. In the stretching area, it’s confusing.

5. Not knowing the rules

I’m not the oldest lifter in my gym — we have a large percentage of seniors — but I’m probably the only one whose institutional memory goes back to the Carter administration. Most of the seniors, and quite a few of the younger members, have never been exposed to gym culture. Courtesies that took many years to become common aren’t intuitive to outsiders.

So consider this my open letter to all health-club novices:

Please don’t block equipment you aren’t using

I don’t understand why someone would stand between two benches to do an exercise that doesn’t require either. I don’t understand why someone would put their towel, water bottle, and clipboard on a box or bench when they aren’t even going to use it. And yet, people do.

Please share

When a new lifter gets a program from a trainer, and he sees he’s supposed to do two sets, he immediately assumes it’s two sets without a break in between. So he’ll do a slow set of 12 to 15 reps, set the weight down, look around for a few seconds, and then start his second slow set of 12 to 15 reps.

I don’t expect him to understand I’m in between sets on that piece of equipment. But I do wish he would step away from the equipment in between sets.

Mostly, though, I wish he understood why his trainer wants him to do two sets, instead of one consecutive set of 25 to 30 reps. He’s supposed to be tired after 12 to 15, and he’s supposed to need a minute to recover … which, conveniently, allows someone like me to squeeze in a set of my own. If he doesn’t need to recover, he’s not doing it right.

Please don’t watch Fox News on the TV in the locker room

And if you absolutely have to, please keep the volume down so the rest of us don’t have to listen to it.

If you’re part of the target audience, great. I’m glad you’ve found each other. But please show some courtesy to the rest of us.

Those are my gripes. What are yours?

August 6, 2012

I’m Still Waiting to Get Too Big

It came up again on a message board last week. A very nice, intelligent, reasonable young woman told the community that she wanted to try the training program in one of the New Rules of Lifting books, but was terrified of getting too big.

Of course we explained to her the reality of her situation: You can’t catch muscularity like the common cold. Nobody bulks up accidentally. It takes years of hard work, not to mention truckloads of food, to build what an objective observer would describe as “bulk.”

I know because I spent much of my life trying to do exactly that. (The photo above is my son when he was 2 years old, I think. His interest in strength training ended shortly after I took the photo.) I appreciate that some people gain weight faster than others, with a combination of muscle and fat. But pure, functional muscle tissue is hard to gain and easy to lose.

Of course anyone’s who lifted for a while understands this. But here’s something I don’t understand as well as I should: Why is strength training a pursuit that so many begin with a firm idea of what they don’t want to accomplish? What else in life works that way?

Success: Eww!

I don’t think any young man or woman has ever gone into a salary negotiation and said to the boss, “I don’t want to get too rich.”

Likewise, I’d be surprised if any author has ever said he didn’t want to sell too many books, or any actress told a director or producer that she didn’t want to get too famous.

When you’re a kid playing a sport for the first time, you don’t think about not hitting home runs, not scoring game-winning goals, or not being the first one to cross the finish line.

Even in adulthood, what runner starts out by telling herself that she never wants to run a 10k, much less finish a marathon, because she doesn’t like the way people look when they’re all tired and sweaty? What novice golfer doesn’t aspire to breaking 100? For that matter, what lifelong golfer doesn’t aspire to breaking 90, or 80, or 70, or, for that matter, accomplishing anything he hasn’t yet accomplished on a golf course?

Looks Don’t Kill, but Why Take the Chance?

I understand that these are silly questions, and you understand I’m deliberately ignoring the single factor that makes strength training different from work, writing, and competitive sports. The goal of strength training, unlike acting or golf, is to change your appearance.

People are fine with performance-oriented goals as long as there’s no risk they’ll end up looking like someone they consider hideous. And these days, we never really see hideous-looking millionaires or athletes. Even among writers, a profession that’s perfectly appropriate for someone whose appearance falls at the far left end of the bell curve, a couple of standard deviations below “average looking,” we mostly just see the good-looking ones. Even the ones who’re certifiably homely, like Stephen King, seem to get less ugly with age and familiarity.

More to the point, nobody looks at Stephen King and thinks, “I don’t want to write a bestseller because I might end up looking like that guy.”

And yet, lots of people recoil with horror when they look at the biggest bodybuilders, powerlifters, and strength athletes. They don’t see guys who tried to get that big, who pushed and pulled massive weights for years to attain their awful size, and who in many cases took a pharmacy worth of illegal drugs to get bigger than their genetics would allow. They see their size as a logical and perhaps inevitable result of lifting weights.

Strength training is the only pursuit I can think of that people enter with the idea that it will change them at the genetic level. The odds that it will change your appearance in a dramatic way are slight. The more likely outcome is a slight change in your appearance.

But that’s the greatest thing about lifting, at least to me. That slight difference tends to be one we cherish right along with our more meaningful career and personal accomplishments. It matters to us because it was hard and because it took time.

And yet, those who’ve never tried it assume it’s all too easy. As a lifetime lifter, I can’t tell you how strange that seems to me, even after hearing it for so many years.

August 2, 2012

Ancestral Nutrition: Which Ancestors Matter?

I spent the first months of the year writing a feature on the paleo diet for Men’s Health magazine. It’s scheduled to appear in the October issue. As part of my research, I asked a company called Warrior Roots to analyze my DNA and tell me where my ancestors came from.

Warrior Roots’ CEO and cofounder, Tom Murphy, is a former college wrestler who has competed in MMA. As you can guess from the company name, there’s a lot of emphasis on warfare.

My interest wasn’t in my ancestors’ weaponry so much as their gastronomy. The paleo diet is based on the notion that you shouldn’t eat anything your ancestors wouldn’t have eaten. So before you jump into it, shouldn’t you at least know who your ancestors were, and from there extrapolate what they had in their diet?

This 1998 paper by Riccardo Baschetti, M.D., makes an elegant argument about the importance of heritage in tackling problems like obesity and diabetes. Europeans and European-Americans have relatively low rates of obesity and diabetes, perhaps because our ancient ancestors have had the longest exposure to grains, dairy, and alcohol. For example, most of us with European ancestry can digest lactose beyond childhood, whereas the majority of humans are lactose intolerant.

Before I get into the roots of my own DNA, I should say that most of us alive today evolved from a small group of humans who migrated out of Africa some 60,000 years ago. (Most Africans, of course, evolved from Africans who never left.) They went to the Middle East, and from there branched out in multiple directions. My European ancestors would’ve gone north or west. Those who went east populated Asia, Australia, and the Americas.

The Cretan Chronicles

Warrior Roots traces DNA from the Y chromosome, the one you get from your father. My father’s mother, Grandma Vivian, was obsessive about tracing our family tree and linking us to historical figures and events. That’s how I know we had an uncle on the Mayflower (John Howland), and that we’re somehow related to William Seward, Lincoln’s secretary of state and the guy who not only bought Alaska, but made bird poop an imperial priority when he was a U.S. senator.

I think Grandma Vivian would roll over in her grave if she knew our Y chromosome comes from haplogroup J2, which originated in the Middle East some 18,000 years ago and spread throughout the Mediterranean, Balkans, the Caucasus, and Iran. It’s associated with the spread of agriculture during the Neolithic period. My ancient ancestors, it seems, went wherever they thought they could grow crops.

My particular Y-DNA is J2a1h-M319, a mutation that arose on the island of Crete about 5,100 years ago. That’s about the time that the great Minoan civilization arose, and the transition point from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. I grew up enthralled by Greek mythology, so to find a genetic connection to one of the great myths was as exciting to me as joining the Daughters of the American Revolution was to my grandmother.

Born and Bread

So what does this have to do with the paleo diet?

For starters, I’m skeptical of any diet that presents itself as one-size-fits-all. It doesn’t matter if it’s low-fat, low-carb, paleo, vegan, or whatever else has come along while I was typing this sentence. Different diets work for different people for different reasons.

As the Baschetti paper explains, the Western diet tends to be a metabolic disaster for populations who’re exposed to it for the first time. Pacific Islanders have the highest obesity rates in the world, and Pima Indians have devastating rates of diabetes. But indigenous populations who still eat whatever their ancestors ate don’t have these problems.

My ancestors would’ve been the first people in the world exposed to diets rich in grains, dairy, and beans. They had hundreds of generations to develop enzymes to process those foods, and defenses against whatever problems those foods create. My particular Y-chromosome strain appears to have arisen on Crete as a direct result of a migration of early farmers and herders to previously unoccupied territory. Put another way, the mutation that created my patrilineal DNA didn’t exist before agriculture. All of my ancestors on my father’s side would’ve been exposed to non-paleo-diet foods like grains and dairy from cradle to grave.

Five thousand years later, my generation is the first to question whether we should eat those foods at all. Which is kind of ironic, considering we probably wouldn’t exist without them.

April 25, 2012

The Game of Life

There are days, I confess, when I just feel old.

Those days seem to accumulate when I’m about to publish a new book. Every little twinge in every little muscle fills me with dread that I’m some kind of fraud. If you could hear my internal dialog … well, okay, if you could actually hear my thoughts you’d get your ass to the nearest neurologist, and I wouldn’t blame you. But if I were to attempt to transcribe my thought process, and you happened to read the transcript, it would go something like this:

Great. Another abdominal injury. The guy who wrote a book about core training can’t keep his own damned core in one piece. What’s the matter with me? Maybe I’m just too old for this …

At some point I shut this pointless prattle down (I’m a big fan of thought-stopping). My go-to move is to remind myself that I’m 55 years old, I’ve been lifting weights three times a week since I was 13, and of course I’m going to tweak, pull, and occasionally tear a muscle. I’m never happy about it, but if nothing else it shows I’m still trying.

Then again, “trying” is the wrong word. As famously said, “There is no try.” I’m not trying. I’m training. This is one of my favorite passages from NROL for Life:

The hierarchy of physical training goes something like this:

1. Physical activity is everything you do when you aren’t at rest. It’s basic movement, with no goal beyond getting from one place to another.

2. Exercise is movement you do on purpose. It includes sports practice, jogging, yoga, backpacking, swimming, cycling, or anything else you think is important enough to take precedence over all the other things you could be doing at that moment. (New Rule #2a: If you can operate your cell phone while exercising, you aren’t actually exercising. You’re just proving you can walk and chew gum at the same time.)

3. A workout is an exercise session that’s deliberately strenuous. You start with the goal of working up a sweat, pushing your muscles and your circulatory system toward their limit, and giving your body a challenge from which it will have to recover.

4. Training is a system of workouts designed to achieve specific biological adaptations.

The more physical activity you get, and the less time you spend sitting, the better. Some of that activity should be purposeful enough to qualify as exercise. More exercise is generally better than less. A workout is even better, but there are only so many true workouts you can do in a week, a month, or a year. A workout that’s also a training session is usually best of all, because you aren’t just testing yourself to see what you can do now. You’re forcing your body to make adaptations that will produce better performances in the future.

I admit I should get more exercise. It really is wrong for a guy who writes about fitness for a living to spend so many hours sitting in front of a computer. But when it comes to training, I don’t have many regrets. Sure, if I could go back in time I’d change all kinds of things. Since I can’t, the best I can do is have a solid training session today. That’s how I felt about Monday’s workout, and how I think I’ll feel about Friday’s. The workouts change, but the goal remains the same: to get better at something.

That’s why Alwyn and I continue writing workout books. He’s always looking for better ways to train his clients, and I’m always looking for better ways to train myself, along with better exercises, methods, and techniques to share with readers.

I explain the genesis of NROL for Life in this excerpt on Facebook, noting that readers like you had to talk us into doing a book for older, increasingly broken-down lifters — that is, for people like me.

It’s all true. But it’s only part of the story. The part I left out is the ulterior motive I just described: I need new ways to keep my 55-year-old body from falling apart. That’s why NROL for Life has more exercises, more information, and more training options than any book in the series.

My internal dialog scolds me for saying such a thing, knowing I’m going to saying something similar about the next book, and perhaps the one after that.

In my defense, though, I mean it every time. Each book starts with a training program from Alwyn that surpasses its predecessors. Then I force myself to write a book that’s a worthy vehicle for those workouts. I do it for a living, yes. And of course I do it for you; there’s nothing more gratifying than hearing from readers whose bodies and lives have been transformed by the magic of a great training program. But I’d be lying if I failed to disclose that I also do it for me.

Sometimes I get a little too ambitious with these new programs, and force asunder parts of my anatomy that would otherwise have remained intact. But I’ll accept an occasional boo-boo if the reward is more ability this week than I had last week.

That’s a fair trade, I think.

If you agree, I hope you’ll check out The New Rules of Lifting for Life. I’ll thank you now in hopes that you’ll thank Alwyn and me later.

March 28, 2012

Creatine, Protein, and Newsletters

Nick Tumminello approached me a few months back with an intriguing project: He wanted to put together state-of-the-art research summaries on creatine and protein, combining and building on work from Joey Antonio, Alan Aragon, Brad Schoenfeld, and several other friends and colleagues.

Being a sucker for time-consuming, detailed work that offers no compensation, I signed on.

It's totally free. Download it to your computer by clicking on the cover (or this link), read it, share it with your friends.

If you like it, we also have a free protein report. When you click the link, you'll discover the diabolical reason why we did all this work for two reports we're giving away: We want you on our private email lists. And once we have you on our lists …

Actually, nothing much happens after that. We send you occasional newsletters alerting you to new material on our websites, new books and articles, or thoughts about what's going on in the training and nutrition fields. And of course you can opt off the lists anytime you want, if you think a life without news of my latest book is worth living.

Hope you like the reports!

January 18, 2012

Obesity: The Final Answer

I recently found myself in a friendly argument over the origins of the obesity epidemic. It (the argument, not the epidemic) started with a post on my Facebook page (scroll down to January 2), which itself came from this article on weight loss in the New York Times Magazine.

The argument was over how much of the rise in obesity can be attributed to genetics vs. environment. Anoop Balachandran, a fitness professional studying for his Ph.D. in exercise science, argues that it's virtually all genetics, and makes his case on his blog in this post and this one. His biggest point is that the people who are obese today are the people who would've been obese anyway, and what we call an epidemic is a rise in their weight, not an overall fattening of the entire population.

No one in my position wants to accept genetics as the final answer. To paraphrase Lt. Aldo Raine, "We ain't in the excuse-makin' business. We in the killin'-fat business. And cousin, business is a-boomin'."

In the past I've worked hard to show that genes are part of the problem (in this Men's Fitness article from 2005 I'm on the record saying it's 40 percent), but that environment and lifestyle choices still matter. And, for a variety of reasons, our environment has become substantially more fattening since the late 1970s.

For example, take a look at this picture of my siblings and me from the 1970s, and guess how many people in that photo have struggled with their weight. (The answer: five.) Now guess how many ended up obese. (Three.) What do you see in that photo that suggests any of those fit, tanned, and healthy-looking people will end up gaining substantial amounts of weight that they will subsequently struggle to lose? That's my own family, where everyone played sports, everyone worked out, and everyone has gone through life with a higher-than-average concern about his or her personal health.

But here's the wild card: Our father (as I've mentioned in almost every book and several magazine articles) was extremely fat for his generation. If he was in a room, chances are he was the fattest guy there. Our mom was the opposite: skinny and so focused on weight that several of us worry when our kids are within earshot. She's said terrible things about some of them, including my son when he was a roly-poly infant whose entire diet consisted of breast milk. What were we supposed to do, deny him the left breast so he'd learn to settle for whatever he could get from the right?

As I said, five of my siblings have inherited my father's predisposition to easy weight gain, while for two of us, weight control has been relatively easy. Was it all just the luck of the draw? Or was there a range of possibilities for each of us?

Thanks to this paper from a journal called Disease Models & Mechanisms, we have an answer. (Huge thanks to Mike Nelson for the heads-up.) The authors are an international who's who of veteran weight-loss researchers. Their goal was to explain why conventional explanations of obesity, like the set-point theory, are flawed, and what might provide a more durable model.

If obesity is all or mostly a genetic phenomenon, then the set-point theory would explain it. We all have a weight and a body-fat percentage that our bodies want to maintain, and any challenge to that set point will trigger mechanisms that make weight loss impossible to sustain. There might be a small range — perhaps 5 to 10 percent of body weight — that we can control. The rest was genetically determined at conception, more or less.

The authors poke these holes in that argument:

Why are the most affluent members of poor societies, but the poorest members of affluent societies, most prone to obesity? Why are children who watch more TV most susceptible? Why do people gain weight in specific circumstances (college, marriage, or upon moving from Asia to the U.S.)? I love this quote:

If the set point changes in response to our social class, our marital status, or whether or not we watch TV, then it is not a 'set' point.

To replace set-point theory, the authors offer the dual intervention point model. Each of us has an upper and lower intervention point. Your body won't allow your weight to sink below the latter, or rise above the former. The range between my floor and ceiling seems to be relatively small, which is why my weight rarely goes below my current 180 pounds or above 190. But for someone else, it might be huge.

To quote the authors:

Within the gap between upper and lower intervention points is the space where environmental effects on energy balance hold sway. … More broadly, the model can explain the obesity epidemic as a consequence of increased food supplies driving up food intake, while also explaining why only some people become overweight and obese in this obesogenic environment.

So how much of your weight is determined by genes? According to the authors, our current best guess is 65 percent. The rest depends on the life you live and the choices you make.

January 2, 2012

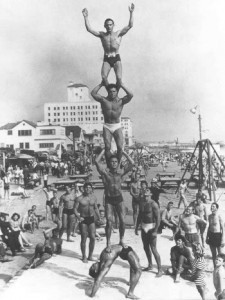

Occupy Muscle Beach!

I love working out in December. The January newbies are long gone. Even the novices who work out with the gym's trainers have mostly given up. It's easy to get to the equipment I need, and to find space to use it. There's an easy camaraderie among those of us who lift 52 weeks a year. Even if we don't know each other by name, we know the woman to the left won't try to step over the bar we're about to lift off the floor, and the guy to the right won't bump into the arm that's pressing a 70-pound dumbbell.

But it's January now, and January is different. January is when you see people you've never seen in your gym before, some of whom are there for the first time. Most of them will be gone by St. Patrick's Day. Some won't last to Valentine's Day. The odds of any of them working out next to you in late December are too small to contemplate.

All the more reason to treat them with courtesy and respect, argues Robin Owens, a moderator at the menshealth.com fitness forum:

Are you ready? The time is near. The time for another occupy movement. Prepare yourselves. It is going to happen Monday morning, Jan 2nd. And it is going to happen in your gym. They are going to move in and set up camp. They are going to take up all the cardio machines; park themselves on the weight machines; leave weights on the floor; curl in the squat rack; spend hours naked at the locker room sink; leave gym towels on empty benches. They are your new 99%.

99%. The amount of people that want to do better this year. The number that wants to be a part of something great. The volume of masses that wish they had what it took. How will you treat them? How will you act toward them? How will you respond when they occupy yourgym? Will you treat them like the 1% that you already know and have come to work with at your gym? Or will you treat them like outcasts?

I challenge you this year to again Be The Example. Lift smart, lift hard and lift with purpose. But also lift with one thing in mind: You are being watched. It does not take a lecture, advice or even a nod of the head to make a difference in the lives of a newb in the gym. It simply takes one small act of respect to encourage one of those 99%ers to come back time and time again.

It's trickier than it sounds. Gym culture is odd and mysterious to people who aren't part of it. If you try to help someone, there's a chance he'll take it the wrong way, like you're big-dogging him or pulling rank.

Besides, where do you begin to point out mistakes to someone who's doing everything wrong? He's using the wrong equipment, or blocking equipment she's not using, or doing something distracting or inappropriate, or just wandering about cluelessly, forcing you to worry about her safety when you should be focused on your form.

That's why I was struck by Robin's advice. Most of us don't consider ourselves to be part of any elite. We're regular people with regular families, muddling along from month to month and year to year. But those of us who show up to lift the first Monday in January because we also showed up to lift the first Monday of every other month are the inner circle of gym culture. We're the ones who wear the knurling off the barbells, and have the calluses to show for it. We're the ones who use the weights on the bottom row of the dumbbell rack. And, without meaning to, we're the ones who can make people feel even more lost and intimidated than they'd otherwise be.

We don't have the power to turn January newbs into lifelong gym rats, like us. It's not our job to teach them what we know. All we can do is go about our business. If someone's paying attention and learning from our example, so much the better.

October 25, 2011

My Reluctant Fast

The first to come after you when you turn 50 is the AARP. Nonstop pressure to join, nonstop pressure to buy useless crap while you're in, and nonstop pressure to rejoin when you quit because you're sick of the AARP selling your address to every company that wants to make a quick buck off people who're slipping into dementia. The second is the healthcare industry, which give you the full-court press for a colonoscopy.

I have nothing against diagnostic procedures in general, but I have a real problem with procedures that require an empty stomach. That's why I minimize blood tests. I'm as concerned about my HDLs as the next guy; I just don't want to have to fast 12 hours to get a reading.

A colonoscopy requires a full 24 hours without food, about 6 of which are spent on the toilet. Looking at the bright side, I figured I'd come out of it lighter, leaner, and totally not full of anything that would earn this post a PG-13 rating.

So here's what happened as I went a day without food for the first time in my life when I wasn't sick:

I got hungry almost immediately, and stayed hungry the entire time. I never felt not hungry.

I felt cold most of the day, until I realized I could drink chicken stock. A few cups of that warmed me up.

I felt distracted and lethargic. I never got that burst of energy you're supposed to get on a fast.

I skipped my workout. I can't train on an empty stomach.

I drank so many fluids that I felt bloated.

I was allowed to drink clear liquids that have calories, so for the first time in memory I had apple juice and Gatorade. Since I never have sports drinks, I didn't realize that 32 ounces of Gatorade has just 213 calories. Add in 3 cups of apple juice, and that's another 350 calories. I don't know how many calories are in the chicken stock, but I'm going to guess I got a week's worth of sodium.

I wish I would've weighed myself before I started. Late in the day, when I was in full bloat, I weighed 195, which is 10 more than normal. This morning, fully depleted, I was at 184.

I'd be lying if I didn't admit I reached the "lighter and leaner" goal. Maybe not a lot lighter, but this morning my stomach looked flatter than it has in months.

I'd also be lying if I said it was anything short of a miserable experience. I've been eating 4 to 6 small meals a day for so long that my body and brain just don't function without them.

I understand my 24 hours of nutritional hell wasn't an actual fast; I never went more than a few hours without some calories, and the 600 calories' worth of carbs, without any protein or fat, is among the worst meal plans imaginable for a health-conscious person.

As soon as I got my release from the butt-probing center, Kimberly and I went to Perkins for a refeed. It was hard to sit up at first — they pump you full of air during the procedure, and it's up to you to deflate on your own schedule — but once I got used to it I was able to put away an omelet, 2 pieces of toast, a glass of orange juice, and one of Kimberly's pancakes. (They're even better than I remember, and as soon as I had one I wanted the rest … which is why I stopped eating them in the first place.)

I'm back to my small-meals-throughout-the-day plan. It may not work perfectly, but it sure beats the alternative.