Gabriel Mckee's Blog: SF Gospel, page 2

March 21, 2011

Adjustment Bureau: Choosing your Destiny

In The Adjustment Bureau, Matt Damon plays a politician named David Norris who gets an accidental peak behind the veil of everyday reality. Right before making a big speech, he runs into an impulsive young lady named Elise in a hotel bathroom. She inspires him to throw his boring old speech out the window and do something off-the-cuff and utterly unforgettable. The speech is a hit, his political future seems assured-- and, we soon learn, Mysterious Forces never want him to see the young lady again. But he does, and before you can say "Dark City" he's being chased around Manhattan by strange guys in fedoras. (Apparently, if you cast John Slattery, you get to borrow freely from Mad Men's costume department.) They're agents-- don't call them angels!-- of a distant and unseen Chairman, who has devised a Plan for Norris, and indeed for the entire world. And those agents will stop at nothing to keep Norris from seeing his inamorata again.

In The Adjustment Bureau, Matt Damon plays a politician named David Norris who gets an accidental peak behind the veil of everyday reality. Right before making a big speech, he runs into an impulsive young lady named Elise in a hotel bathroom. She inspires him to throw his boring old speech out the window and do something off-the-cuff and utterly unforgettable. The speech is a hit, his political future seems assured-- and, we soon learn, Mysterious Forces never want him to see the young lady again. But he does, and before you can say "Dark City" he's being chased around Manhattan by strange guys in fedoras. (Apparently, if you cast John Slattery, you get to borrow freely from Mad Men's costume department.) They're agents-- don't call them angels!-- of a distant and unseen Chairman, who has devised a Plan for Norris, and indeed for the entire world. And those agents will stop at nothing to keep Norris from seeing his inamorata again.

As Gary Westfahl's review ("Philip K., Diminished") points out, The Adjustment Bureau is not so faithful to its source material. That's not, in and of itself, a bad thing: great films are often the result of unfaithfulness to source material. (Heck, look at Blade Runner-- or, more x-tremely, Total Recall!) It's what you do with those changes that matter. Westfahl points out how making the protagonist of the story an up-and-coming politician, rather than insignificant real estate man Ed Fletcher, changes the tone of the story. More disappointing for me is the fact that the film completely chucks out what I consider the centerpiece of the original story: a nightmarish sequence in which the protagonist sees the world around him collapsing into dust and ash. But so be it: that's the name of the adaptation game, right? You take what works, and you leave what doesn't, and maybe that scene just wouldn't have served what George Nolfi (Adjustment Bureau's writer/director) was going for.

So, what was he going for? Adjustment Bureau is rather clever, when it wants to be. I rather like how Norris plays out the proverbially oxymoronic "honest politician" part, the design of the would-be angels' Plan-tracking notebooks, the inventiveness of the early footchases. But all of this culminates in a conclusion that requires a mess of contrived, arbitrary rules; the angels can teleport, but only if they're wearing their magic hats! They're virtually omniscient-- but not around water! (The latter rule implies that every naval battle in history threw humankind off-Plan, but that's another matter.) It starts to feel a bit... silly. Ever see Lady in the Water?

But, more centrally, more naggingly, the concept of God as "Chairman" just doesn't work here. It's one thing to posit a God who works through efficient means, and entirely another to posit God as an arch-bureaucrat, a beancounter of souls. This is far too simplistic a picture of divine providence-- and, moreover, it makes God into not just a foil for our self-determining protagonist, but an outright villain-by-proxy. Furthermore, Norris' rebellion ends up being too darned easy, on an ontological level. His decisions, once he steps outside the prescribed path, are no different than any impulsive decision you've ever made. The centrality of the Plan implies that every impulsive decision we make is predetermined. the story thus requires that Norris's impulsive decisions be ontologically different somehow-- but this never receives an adequate explanation. Sure, his adjustor napped on the job, but this does not sufficiently account for why his will somehow then becomes more free than everyone else's.

But, more centrally, more naggingly, the concept of God as "Chairman" just doesn't work here. It's one thing to posit a God who works through efficient means, and entirely another to posit God as an arch-bureaucrat, a beancounter of souls. This is far too simplistic a picture of divine providence-- and, moreover, it makes God into not just a foil for our self-determining protagonist, but an outright villain-by-proxy. Furthermore, Norris' rebellion ends up being too darned easy, on an ontological level. His decisions, once he steps outside the prescribed path, are no different than any impulsive decision you've ever made. The centrality of the Plan implies that every impulsive decision we make is predetermined. the story thus requires that Norris's impulsive decisions be ontologically different somehow-- but this never receives an adequate explanation. Sure, his adjustor napped on the job, but this does not sufficiently account for why his will somehow then becomes more free than everyone else's.

As for what that freedom is in aid of-- well, tying the "adjustment" that Norris's guardian agent messed up so directly to the Plan's ends serves to streamline the story a bit. In Dick's original the Plan is complex, and the fruits of the adjustment don't become apparent until long after the insignificant protagonist is out of the picture. But that's exactly the point: this is the smallest change possible to achieve some very, very big ends. But Norris, a rising star in national politics, is already part of the big picture, so these means don't end up looking quite so efficient. This doesn't elevate the everyday to cosmic significance-- quite the opposite, in fact. The folks in charge really are the ones that matter, and that's the way it must stay. The angel/agents show a callous disregard for the everyman-- just ask that cab driver who they just "adjusted" into a three-car wreck.

What Adjustment Bureau's characters, divine and otherwise, really care about is a Hollywood romance that doesn't make too much sense. By the end of the movie, we've seen very little reason why Elise should want to be with Norris; he's treated her like crap for much of their relationship, including abandoning her for months at a time, dumping her while she's in the hospital, etc. (Shades of Twilight here.) And yet, by the rules of romantic logic if not by the Plan, their relationship is destined, so their love must conquer all. If anyone is suffering from an absence of free will, it is these characters in the hands of their screenwriter. At the end of the film, when the Chairman-- spoiler alert!-- abolishes the Plan and hands the reins back to humankind, we haven't been given enough evidence to support believing it's a good thing. Sure, these two get to be together, hooray-credits-roll, but we've already been told that the last time this happened it led directly to the Holocaust. God may have declared this was all a test, but you have to question why he passed: all we've seen him do is make impulsive decisions, consequences be damned. As Jay Michaelson asks in his review for Religion Dispatches, is that really the path we should be leading ourselves down?

In any event, what the film has done by its conclusion is completely invert the attitude of the original story toward predetermination. By the end of "Adjustment Team," Dick's Ed Fletcher has come to a shaky acceptance that our world is controlled by incomprehensible forces. It's a bit like an optimistic Lovecraft story: Fletcher sees behind the veil, and is driven, not to insanity, but to a nervous but respectful understanding. Later in his life, Dick became an admirer of Nicolas Malebranche, a medieval theologian who saw God as the only true actor in every event in the universe: created reality, including human beings, is just a gathering of "occasions" for divine action. Adjustment Bureau just won't have it: its libertarian, if not Nietzschean, dedication to the individual will will brook no consideration of the Chairman's point of view, let alone a really omnipotent deity like that of Malebranche.

But enough of the big words: is it a good movie? I could say that it's better than I've just made it sound. But here's a more appropriate answer: I'm not at liberty to say...

March 17, 2011

Philip K. Dick adaptations ranked

Nerve recently asked me to rank and briefly review all of the Philip K. Dick movie adaptations to date. The results are here. I deliberately, but truthfully, went against the conventional wisdom on Blade Runner, which I never thought quite lived up to the hype, at least in terms of narrative and character. Which isn't to say I dislike it-- not at all, in fact-- but I am definitely not inclined to knee-jerk it into the #1 slot. And yeah, I missed Barjo, the French adaptation of Confessions of a Crap Artist, which has yet to be released on DVD, and has been out of print on VHS for, oh, 20 years or so. I would, however, like to give an honorable mention to the oft-overlooked TV series Total Recall 2070, which is far better than you'd expect from a canceled-after-on-season Canadian-produced SF show of the late '90s.

You will also note a capsule review of Adjustment Bureau in that list. Where is the full review, you ask? It is, after all, an SF film with God as the hero's main antagonist. Short answer: it's coming, soon. In the meantime, there are two very thoughtful reviews of the film worth reading. For Locus, Gary Westfahl details the extent to which Dick's story "Adjustment Team" went out the window in this adaptation, calling into question the very nature of adaptation. Regardless of your opinion on the film, it's a great essay. And for Religion Dispatches, Jay Michaelson (though much more kindly disposed to the film than Westfahl) finds fault with the way it frames, and solves, the question of free will vs. divine providence. Your homework, reader, is to take a look at those two essays; my review (hopefully up in a day or two) will touch on a few of the same points.

March 7, 2011

"That Leviathan, Whom Thou Hast Made": Mormon Sun-Whales!

The single most up-my-alley story of the last year has been nominated for a Nebula Award: Eric James Stone's "That Leviathan, Whom Thou Hast Made," published in the September 2010 issue of Analog. It's the story of Harry Malan, a Mormon not-really-missionary living on a science station orbiting the sun. He's not a scientist-- he's a banker, sent to make stock trades based on solar gas-mining operations, which he can do with an eight-minute lead over his Earthbound competitors-- so he's understandably not too knowledgeable about the natives. Yes, the sun has natives: enormous plasma beings called "swales" or "solcetaceans." A handful of these enormous sun-whales have converted to Mormonism, and Malan-- who is, almost by default, the leader of the sun station's Mormon congregation-- is thrown into both a moral dilemma and a diplomatic debacle when one of his swale congregants complains of having been forced into sexual contact by a larger, older swale. The swales have very different ideas about sex and consent than humans do, but Malan can't help but view the situation through the lens of human laws and customs: a member of his flock has been raped, and he sets out to right the perceived wrong. The plot soon thickens when Malan finds himself embroiled in a power struggle with Leviathan, the oldest known swale, who claims to be the originator of its entire species, and possibly the oldest living thing in the entire galaxy-- certainly something akin to a god. And this god is angry about being questioned by lesser beings.

The single most up-my-alley story of the last year has been nominated for a Nebula Award: Eric James Stone's "That Leviathan, Whom Thou Hast Made," published in the September 2010 issue of Analog. It's the story of Harry Malan, a Mormon not-really-missionary living on a science station orbiting the sun. He's not a scientist-- he's a banker, sent to make stock trades based on solar gas-mining operations, which he can do with an eight-minute lead over his Earthbound competitors-- so he's understandably not too knowledgeable about the natives. Yes, the sun has natives: enormous plasma beings called "swales" or "solcetaceans." A handful of these enormous sun-whales have converted to Mormonism, and Malan-- who is, almost by default, the leader of the sun station's Mormon congregation-- is thrown into both a moral dilemma and a diplomatic debacle when one of his swale congregants complains of having been forced into sexual contact by a larger, older swale. The swales have very different ideas about sex and consent than humans do, but Malan can't help but view the situation through the lens of human laws and customs: a member of his flock has been raped, and he sets out to right the perceived wrong. The plot soon thickens when Malan finds himself embroiled in a power struggle with Leviathan, the oldest known swale, who claims to be the originator of its entire species, and possibly the oldest living thing in the entire galaxy-- certainly something akin to a god. And this god is angry about being questioned by lesser beings.

Stone's story is chock full of scriptural allusions to the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon-- some stated plainly, others less so. Most intriguing for me is the Job-like confrontation at the story's end between the finite Malan and the all-but-infinite Leviathan. The idea that limited, contingent, mortal beings can have some influence and importance in the infinite, eternal eyes of the deity is, arguably, the core of all human religion. Stone's story presents this concept in the context of a speculative ethical puzzle, and is quite entertaining to boot. Its Nebula nomination is well earned.

Through the end of March, you can read "That Leviathan, Whom Thou Hast Made" for free on Stone's website.

March 6, 2011

Recent reading roundup

I recently bought a complete run of my favorite SF magazine-- If, later known as Worlds of If. Which is great-- but I need to make some room for it. And that needs I need to clear off the shelf that's been holding all the books I've wanted to write something about for the last, oh, 16 months or so... So, in the order they're piled up next to me...

I recently bought a complete run of my favorite SF magazine-- If, later known as Worlds of If. Which is great-- but I need to make some room for it. And that needs I need to clear off the shelf that's been holding all the books I've wanted to write something about for the last, oh, 16 months or so... So, in the order they're piled up next to me...

I Am Not a Serial Killer and Mr. Monster by Dan Wells

I mentioned these in my "best things I read this year" list for SF Signal's Mind Meld a couple months ago. They're not SF, but rather supernatural young adult mysteries with a horror edge (or is that horror stories with a mystery edge?). They're of some interest for, surprisingly enough, Dickian reasons: their protagonist is a teenage sociopath who desperately wants not to end up a serial killer (hence the title of the first book). I liked Wells' approach to his emotionless hero: this is a portrait of PKD's "android mind" from the inside. (Credit this connection to my recent research and writing about Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?).

Doctor Who: The Coming of the Terraphiles by Michael Moorcock

Doctor Who: The Coming of the Terraphiles by Michael Moorcock

Pretty good stuff, though a bit slow to start. I am not too big a fan of Moorcock's Jerry Cornelius novels-- the first one is good, but feels like juvenilia; the three that follow are... let's say "meandering." (I suspect I'd like the short stories more.) The first hundred pages of Terraphiles meanders in a similar way, basically depicting the teatime conversations of a handful of far-future socialites. Wikipedia tells me it's an homage to Wodehouse. Shrug. But when the classic Moorcock mythology starts up, things get a bit more interesting-- the whole "struggle for balance between the cosmic forces of Law and Chaos" thing is exactly the sort of scale that Doctor Who thrives on. And there are a couple characters that would have fit brilliantly in the Tom Baker era-- the two-headed space pirate Frank/Freddie Force and his Antimatter Men are particularly inspired. This definitely made me want to dig a bit deeper into Moorcock's more deliberately mythological stories, certainly.

Makers is basically a novel about Disney World-- I think it's a deliberate update/cannibalization of the ideas from Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom. The central characters are a pair of culture-hacking inventors who create a theme park-cum-art installation that can be identically reproduced anywhere in the world, and is entirely open-souce and modifiable by any user-- basically the polar opposite of the rigidly controlled Disney ideal. What interested me most in the novel was the extent to which "the ride" becomes a sort of religion for its devotees. One character, a one-time Disney devotee who goes by the ubergoth nickname "Death Waits," puts it this way: "There had been a time... when he'd really felt like he was part of the magic. No, the Magic, with capital letters. Something about the shared experience of going to a place with people and having an experience with them, that was special. It must be why people went to church." This reminds me of something. I rather like Doctorow's novels, but I rarely find anything to say about them; religion is not exactly high on his list of priorities. The one thing I hated about Eastern Standard Tribe-- probably my second-favorite of his books that I've read, next to Little Brother-- he wrote my alma mater out of history. At one point, a character states that Harvard doesn't have a divinity school. In the audio version of the novel, Doctorow puts in an aside saying that he had received a number of e-mails about this, and that the point of this statement was to say that "they don't have one... in the future," or something to that effect. I just don't buy it, and I don't see what the point is. There's a lot of questions begged by such a minor detail-- not just questions about cultural shift, which I assume is what he was getting at, but questions about institutional politics and departmental financing. HDS has been there for a couple centuries, and it's not going to disappear so quickly that people in a near-future novel should be able to get away with assuming it doesn't exist. (end slightly ranty aside). So, yeah, Disneyland as a religion. That's pretty interesting, and the first hint I've seen in any of Doctorow's works in the direction of some sort of understanding of the kind of communal experience that is central to a lot of people's experience of religion.

Pleasure Model and The Bloodstained Man by Christopher Rowley

No theology here, but something worth noting, however briefly. These are the first two novels in Tor's "Heavy Metal Pulp" line, a series of self-consciously pulpy adult-theme-filled SF, à la Heavy Metal magazine. I didn't go into these with high expectations, but I was impressed with the spirit of fun in these books-- they read like a particularly compelling half of a good Ace Double.

The Cardboard Universe: A Guide to the World of Phoebus K. Dank by Christopher Miller

An intriguing book from its form alone: this book is written in the form of an encyclopedia on the work of its imaginary titular character, with alphabetically-organized entries written by two of the foremost experts on his life and work, who happen to deeply hate each other. At first I thought its picture of "Dank" was a bit too cruel a caricature of Philip K. Dick, but it soon became clear that Dank has very little to do with Dick at all, initials aside. He's more like a cross between Kilgore Trout and Ignatius J. Reilly from Confederacy of Dunces: an off-putting, obese imbecile who writes intriguing trash. One of the two encyclopedia authors hates Dank, which reminded me of Thomas Disch's slanderous The Word of God. But other than that, the PKD material in this novel is all on the surface. It's an entertaining book, to be sure, but trying to read PKD into its title character-- or vice versa-- would be headache-inducing, so it's best not to try.

I picked this up after reading Adam Roberts' brief mention of it in his History of Science Fiction (which was excellent-- hopefully more on that soon)-- Roberts calls it one of the best SF novels of 1987, arguing that it was overlooked because it was a licensed tie-in novel rather than a standalone "literary" work. I have some growing bibliographical interest in licensed novels, so I figured this might be a good one to look into. I don't know that I can entirely agree with Roberts' accolade-- I'd have to see what else was published that year-- but it was definitely enjoyable. Most intriguing to me was the novel's explanation of Vulcan theology. According to Duane, the presence of God is not a mystery or a matter of faith for Vulcans, but a reality that they experience directly. The Vulcan word for this is a'Tha, translateable as "immanence." Spock states: "a'Tha is the direct experience of the being or force responsible for the creation and maintenance of the Universe... Vulcans experience that presence directly and constantly. They always have, to varying degrees. The word is one of the oldest known, one of the first ever found written, and is the same in almost all of the ancient languages." Spock even implies that this constant experience of the divine may be one of the driving forces behind Vulcan logical enquiry:

"Humans have no innate certainty on this subject and therefore must hink it would solve a great deal. In some ways it does. But there are many, many questions that this certainy still leaves unresolved, and more that it raises. Granted that God exists: why then does evil do so? Why is there entropy? Is the force that made the Universe one that we would term good? What is good? And if it is, why is pain permitted? ... They are all the same questions that humans ask, and no more answered by a sense of the existence of God than of His nonexistence... It takes more than the mere sense of God to create peace. One must decide what to do with the information."

Haldeman's 1997 novel is a thematic sequel of sorts to his 1974 classic The Forever War (discussed here)-- it takes place in an entirely different universe, but explores similar ideas of the morality of war and peace. Forever Peace is centered on wars fought remotely, with professional soldiers undergoing extensive surgery to allow them to control distant robotic soldierboys." Most of the world south of the Tropic of Cancer is embroiled in permanent war, with U.S. corporations funding soldierboy invasions to repress guerrilla rebellions. The main plot involves two discoveries that threaten this world's status quo-- one of a doomsday weapon that could recreate the Big Bang; the other of a means for eliminating human aggression using the "jacking" technology behind the soldierboys. The apocalyptic implications of the first are clear. It's the moral conundrum posed by the second that I find the most interesting. Enlightenment-style humanism is the moral bedrock of much SF, according to which free will is an absolute good above pretty much all others. The bad guys brainwash; we know the good guys have won when their freedom to choose is no longer threatened. Forever Peace throws that moral picture into question. If we really did have a means of eliminating aggression and fostering permanent peace, how much would it matter if some portion of free will were thereby suppressed? If literally countless lives could be saved, isn't that worth more? In this novel, the possibility to eliminate the greatest human evil moves from theory to reality, and its use is urgent. I'm reminded of the doctrine of "expedient means" laid out in the classic Buddhist text the Lotus Sutra. In this text, the Buddha tells a parable about a burning house full of children who don't know it's burning, and don't want to leave. So their father tells them a lie-- that there are three spectacular kinds of carts for them to ride on, far more fun than any of their toys inside. When the children arrive outside, he gives them all the same kind of cart to carry them to safety. They may be disappointed-- but at least they won't burn to death. In the Lotus Sutra, this parable is intended to explain how the varying practices of the three main branches of Buddhism can lead to the same goal: the means are not important, but the end-- nirvana and the end of suffering-- is. Where suffering is involved, the Lotus Sutra argues, the ends justify the means. Forever Peace applies this argument to the question of war. Wouldn't true and lasting peace be worth the sacrifice of that portion of free will that makes war possible?

January 29, 2011

The Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick, 1980-1982

The issue of the SFRA Review containing my review of The Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick vol. 5: 1980-1982 has been posted at the SFRA's website. An excerpt:

The issue of the SFRA Review containing my review of The Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick vol. 5: 1980-1982 has been posted at the SFRA's website. An excerpt:

Those familiar with the previous volumes of Dick's letters will know, more or less, what to expect of this one. Dick is still exploring and expounding upon his religious experiences of early 1974, and much of this volume consists of extended philosophical speculations. (Indeed, most of the book's first hundred pages are a single series of letters sent to Patricia Warrick, author of Mind in Motion: The Fiction of Philip K. Dick,in January 1981). But philosophical exegesis is not all that was going on in Dick's life and mind in this period, and this volume presents vital information about other aspects of his work as well. Dick's final two novels—The Divine Invasion and The Transmigration of Timothy Archer—were written during this period, and several letters shed light on their composition. A pair of letters to Ursula K. Le Guin (137 and 150–151) show Dick reflecting on the often-problematic nature of his female characters, and even suggest that Angel Archer, the protagonist of Transmigration and undoubtedly Dick's most carefully thought-out female character, grew at least in part in response to Le Guin's criticisms. Two letters (to Russell Galen, 89–92, and to David Hartwell, 154–156) contain detailed plot outlines for novels that were never written. Elsewhere, we can glean information about Dick's knowledge of William S. Burroughs (145), Alfred North Whitehead (148), and Martin Luther (251). Other letters show Dick's thoughts on the publication of VALIS and his response to the novel's reviews, his shifting opinions on the film Blade Runner, and his brief love affair, a mere four months before his death, with a young woman known only as "Sandra." Needless to say, there is much to reward the PKD researcher in this volume.

Read the full review, plus the rest of the issue, here (it's on p. 9-10 of the PDF).

January 26, 2011

"Against textual idealism"

Rob Latham's short piece "Against Textual Idealism," published a few years ago but first read by me a couple days ago, hits all the right notes for me as a librarian, scholar, and collector of SF:

It matters intimately to an informed grasp of Dickens' novels, for example, that most of them were released in serial form, an arrangement that had appreciable effects on such intra-textual features as plot and characterization. Every text, whether an original publication or a reprint, is materially instantiated in a specific medium, accessible through particular modes of distribution, and amenable to discrete forms of reception. Encountering a story by H.P. Lovecraft or Dashiell Hammett in a pulp magazine such as Weird Tales or Black Mask is not the same thing as reading it in a Library of America edition.

I can't say it better, so you might as well just read the whole thing. (To tie it into issues of recent relevance, I think these issues of textual interpretation are more than relevant to Richard Dawkins' unrefined and totalizing view of the Bible. On a more gut and personal level, though, it just means it's way more fun to read an issue of Galaxy than a clothbound scholarly edition.)

January 25, 2011

Richard Dawkins and religious discrimination

Regulars here know I'm no fan of Richard Dawkins, but even I was surprised at his latest article for Boing Boing. Discussing the recent lawsuit between astronomer C. Martin Gaskell and the University of Kentucky, Dawkins goes lower than I thought he dared, stopping just this side of libel against a fellow scientist.

Regulars here know I'm no fan of Richard Dawkins, but even I was surprised at his latest article for Boing Boing. Discussing the recent lawsuit between astronomer C. Martin Gaskell and the University of Kentucky, Dawkins goes lower than I thought he dared, stopping just this side of libel against a fellow scientist.

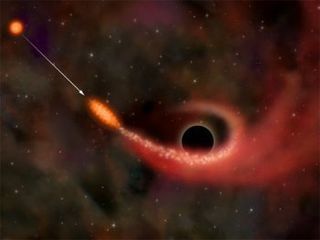

Some background: in 2007, Gaskell was up for a position at the University of Kentucky. He was a hot contender, but one of the members of the search committee researched his religious beliefs and concluded that he was "potentially evangelical." He was questioned about his faith in his interview, and ultimately didn't get the job-- despite, according to one committee member, being "breathtakingly above the other applicants in background and experience." E-mails sent among the search committee submitted as evidence in the case make it clear that Gaskell's religious beliefs-- which don't play a role in any of his peer-reviewed work on quasars and supermassive black holes-- were pretty much the only factor in the committee's decision not to hire him. Gaskell is not a creationist, and accepts the theory of evolution-- things which would be unlikely to turn up in his work anyway. All of which renders that phrase "potentially evangelical" even more chilling. Gaskell was rejected not because he wasn't the right guy for the job, and not even because his beliefs conflicted with his duties. He wasn't even rejected for beliefs that he actually held. He was rejected because of his membership in a group that also contains individuals whose beliefs are in conflict with a related department to the one in which he was applying to teach. It was a clear-cut case of religious discrimination, and the school has settled the case out of court for $125,000.

Enter Dawkins, who concludes from this that all kinds of beliefs, religious and otherwise, should justly and rightly serve as grounds for dismissal or rejection of employment, laying out several hypothetical cases-- none of them bearing more than a superficial resemblance to the Gaskell case-- in which he feels discrimination would be just. He even laments that "the word 'discriminate' carries such unfortunate baggage." The piece reads like an opening salvo in a witch hunt for "the creationists among us": it is a call for greater prejudice.

The entire argument rests on the faulty assumption that religious ideas are protected and non-religious ideas are not. I'm no lawyer, but it seems to me that if I were dismissed from my job because I believe in a subterranean super-race of mole people, I would start taking notes for my wrongful dismissal suit. Unless that belief interferes with my completion of assigned tasks (I am an excavator operator who will not break ground on a building project for fear of angering the mole people) or it interferes with my coworkers, clients, or customers (sales are down at the hardware store because I keep scaring people away with talk of their underground masters when all they wanted to do was buy a hammer). My personal beliefs-- religious or otherwise-- are personal, and if they don't interfere with my job, then there is no cause for termination.

In the Gaskell case, of course, it's even more preposterous: Gaskell doesn't believe that the Earth is 6,000 years old any more than he believes that the mole people are preparing to reclaim the surface world. But Dawkins' entire article is framed to mislead the reader into believing Gaskell is a secret creationist. The attempt to paint Gaskell with the creationist brush has its roots deep in Dawkins' views of religion in general, and the idea of God in particular. Dawkins will only grant that Gaskell "claims... that he is not a full-blooded YEC [young earth creationist]." For Dawkins it can only be a "claim," not a fact, and that use of "full-blooded" shows that he is only capable of considering religious people as holding some degree of creationist ideas. Dawkins includes a selectively-clipped quote from Gaskell, " I have a lot of respect for people who hold this view because they are strongly committed to the Bible," Dawkins quotes. A-ha! A creationist! But here's the remainder of the quote: "...but I don't believe it is the interpretation the Bible requires of itself, and it certainly clashes head-on with science." Gaskell does what Dawkins cannot: see multiple ways of reading a text.

In The God Delusion, Dawkins misdefines the word "God" as denoting an intelligent designer. He builds creationism into the very idea of belief in God. Thus he is beyond perplexed at someone like Gaskell, who believes in both God and evolution. He simply can't comprehend people who find meaning in the Bible without also believing that the Earth is 6,000 years old. Dawkins has drawn boxes for us all to fit in-- "deluded creationist," "'bright' atheist." When presented with someone who doesn't fit in those boxes, his brain shuts down. This is a fact: not all believers are creationists. The data do not fit Dawkins' theoretical model. But rather than reframe his hypothesis, Dawkins continues to insist that his model is correct. His ideas about faith are nothing more than bad science.

The worse thing, though, is the other thing that Dawkins' article intends to do: to suggest that the Unversity of Kentucky's discrimination against Gaskell was justified. If you read waaaaay down into the comments section, he backpedals, claiming that "Nowhere in my article did I say that Gaskell himself should not have got the job," and that he did not intend to discuss the Gaskell case-- begging the question of why, if his hypotheticals don't apply to the case at hand, he bothered to frame the article with it at all. But even if we take those hypothetical situations as "preposterous examples," we are left with the distinct sense that Dawkins is not content with his quest to rid the world of religion. He also wants to rid the world of the strange, the eccentric, and the wacky. I have long felt that Dawkins must be, at heart, a profoundly boring person, for his insistence that the world must actually be as he conceives it. This article cements that opinion. I would not want to live in Dawkins' perfect world, because it would be a world of profound and fathomless sameness. We need our eccentrics. We need preposterous ideas, for how else will we be shaken out of our false beliefs, unless challenged with what we know must be impossible? Give me the bizarre, the preposterous, and yes, the delusional: better that than the bleak unity of a world squeezed into neat, pseudo-empirical boxes.

January 20, 2011

What I've been doing lately:

Don't mistake the sluggishness of this blog for inactivity: there's been much going on behind the scenes lately. Most relevant to our purposes here are a couple of Philip K. Dick-related writing projects. I wrote a review of the final volume of the Selected Letters for the SFRA Review. It's not yet available online, but it will hopefully be up soon at the SFRA's website. (I may post it here soon as well.) More importantly, I have a forthcoming essay in Boom! Studios' comics adaptation of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? My piece, which looks at the theological and ethical content of DADOES (but not quite so boringly as I just made it sound), will appear in #21, due out sometime in March. I'm told that issue also includes some major material relating to the empathy-based religion of Mercerism and its enigmatic messiah, Wilbur Mercer-- quite appropriate, I think.

Don't mistake the sluggishness of this blog for inactivity: there's been much going on behind the scenes lately. Most relevant to our purposes here are a couple of Philip K. Dick-related writing projects. I wrote a review of the final volume of the Selected Letters for the SFRA Review. It's not yet available online, but it will hopefully be up soon at the SFRA's website. (I may post it here soon as well.) More importantly, I have a forthcoming essay in Boom! Studios' comics adaptation of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? My piece, which looks at the theological and ethical content of DADOES (but not quite so boringly as I just made it sound), will appear in #21, due out sometime in March. I'm told that issue also includes some major material relating to the empathy-based religion of Mercerism and its enigmatic messiah, Wilbur Mercer-- quite appropriate, I think.

Then there's my best-things-I-read-this-year roundup for SF Signal's Mind Meld, which you can read here. I hope to return to this soon with a bit more robust listing of recently-read materials. (I've been kicking myself since late December because I completely forgot to mention what was actually the best thing I read last year-- C.M. Kornbluth and Frederik Pohl's The Space Merchants, which is every bit as good as you've heard and more.)

Less theologically-relevant, but certainly no less fun, I've been involved in the operation of a gallery show featuring the work of the Sucklord, easily the best artist working in the art-toy idiom. His bootleg toys, mostly cast in resin from remixed molds, are irritating, hilarious, and firmly rooted in a brand of nerdishness that I appreciate greatly. The Suckadelic universe contains only supervillains, with names like "Star Chump" and "Galactic Jerkbag." The Sucklord's primary reference points are in the Star Wars realm, but my favorite piece is a bit more obscure:

The Salarystak is the middle piece in a series that also includes the "Altrusian"--a simple-yet-elegant knockoff of Land of the Lost's Sleestak--and the Starstak, a highly-evolved future form of the same. In addition to the great visual, I love the SFnal moral dilemma that the Salarystak embodies:

"To which end of the spectrum is his pendulum swinging? He knows not, for he is ignorant of his place in the temporal timeline. He has closed the mental door of escape and filled the void with his Career, his family, his mortgage, his car, and his martinis. Only in his deepest subconscious lies the dim comprehension that there is a bigger picture and something greater is at stake..."

Of course, in the world of the Sucklord, a triptych is presented as a multi-figure blister-pack:

There is a very good chance that I'll be adding that little item to my collection before the show closes on January 23rd. Another contender, this one with a bit more theological flavor to it: A series of four Greek-ish gods, presented as supervillains, who govern everyday disappointments: Chronos (wasted time), Tyros (insufficient income), Daemos (aches and pains), Mordros (general aimlessness), Eros (a broken heart). Nicest touch: their heads are polyhedral dice. You can check out what's for sale in the current gallery show at Suckshoppe.com and peruse the exhibit catalog below (warning: it's not for the faint of heart, the easily-offended, or those with good taste in general).

December 9, 2010

Doomsday Film Festival

Don't think the prolonged quiet on this blog is due to inactivity-- quite the opposite. For instance: I'll be speaking on a panel this Saturday at the Doomsday Film Festival in Brooklyn, N.Y. I'm speaking after the late-Cold War anxiety tale Testament. But if you're interested you might as well just get the festival pass, because the entire lineup looks amazing! (I'm most looking forward to Damnation Alley and Hardware.) Buy your tickets soon, because by all accounts the theater is tiny (like a fallout shelter, natch). The festival begins tomorrow night (Friday, Dec. 10th), and my film and panel session begin at 3:30 on Saturday the 11th. See you at the end of the world!

Don't think the prolonged quiet on this blog is due to inactivity-- quite the opposite. For instance: I'll be speaking on a panel this Saturday at the Doomsday Film Festival in Brooklyn, N.Y. I'm speaking after the late-Cold War anxiety tale Testament. But if you're interested you might as well just get the festival pass, because the entire lineup looks amazing! (I'm most looking forward to Damnation Alley and Hardware.) Buy your tickets soon, because by all accounts the theater is tiny (like a fallout shelter, natch). The festival begins tomorrow night (Friday, Dec. 10th), and my film and panel session begin at 3:30 on Saturday the 11th. See you at the end of the world!

October 10, 2010

Radio Free Albemuth: The politics of mystical experience

Radio Free Albemuth is generally considered an oddity in the Philip K. Dick canon. Initially entitled Valisystem A, it was Dick's first attempt at transforming his religious experiences into a novel. When he sent it in to a publisher they returned it with a request for minor revisions; instead he scrapped the whole thing and started from scratch, resulting in the masterful Valis. Valisystem A was essentially forgotten until three years after his death, when it was published under the title it's known by today. There is disagreement among the grand assembly of Dickheads over the relative quality of many of his lesser-known books, but perhaps none is so controversial as RFA. Some think it is a minor footnote in the grander story of Valis (Jonathan Lethem, who left it out of the third Library of America novel in favor of A Maze of Death,* is in this camp); but others-- myself among them-- think it's an overlooked masterpiece, a powerful fusion of theological exploration and science-fictional storytelling.

Radio Free Albemuth is generally considered an oddity in the Philip K. Dick canon. Initially entitled Valisystem A, it was Dick's first attempt at transforming his religious experiences into a novel. When he sent it in to a publisher they returned it with a request for minor revisions; instead he scrapped the whole thing and started from scratch, resulting in the masterful Valis. Valisystem A was essentially forgotten until three years after his death, when it was published under the title it's known by today. There is disagreement among the grand assembly of Dickheads over the relative quality of many of his lesser-known books, but perhaps none is so controversial as RFA. Some think it is a minor footnote in the grander story of Valis (Jonathan Lethem, who left it out of the third Library of America novel in favor of A Maze of Death,* is in this camp); but others-- myself among them-- think it's an overlooked masterpiece, a powerful fusion of theological exploration and science-fictional storytelling.

John Alan Simon, the writer, producer, and director of the recent independent film adaptation of Radio Free Albemuth, clearly falls into the latter camp, as evidenced by his ardently faithful adaptation. It's obviously a labor of love, as underscored by the story of the film's production: Simon has been working on the adaptation for over 15 years. The screenplay hews closely to the novel in both structure and content-- something that no other PKD adaptation has done except A Scanner Darkly. The story is all there: Nicholas Brady, a PKD stand-in, is contacted by a semi-divine alien satellite that hopes to rescue humankind from the ontological injustice underlying not only a growing fascism in the United States, but all human suffering everywhere. His friend, the science fiction author Philip K. Dick, is gradually pulled into Brady's understanding of the world and his attempts at revolutionary action-- an action that cannot be judged in worldly terms of success or failure. The film transcribes the story with painstaking care.

That's not to say there isn't some creative interpretation going on, but the film handles that interpretation smartly. This is especially evident in the numerous dream sequences: the dreams of PKD stand-in Nicholas Brady are a central aspect of the novel (and of Dick's real-life religious experiences), and the film captures the otherworldly quality of those dreams brilliantly. (The bemused look on the face of Jonathan Scarfe, playing Brady, as he receives a computerized message from an alternate-universe "Portuguese States of America" is a particular high point). The film uses an awful lot of computer effects for a movie without a car chase, and those effects pay off-- they are an otherworldly intrusion, just like the alien-divine messages they represent. There's a slightly different look to each dream, including a couple fully-animated sequences. Some are extremely polished; others are deliberately more sketchy, but there's a powerful aesthetic driving all of these sequences. It's clear that a lot of thought went into the look of Brady's visions, which are, after all, the backbone of this story.

There's also a strong emphasis placed on the novel's political message. It gives a sinister illustriation of an America gradually transforming into a police state that reminded me of Southland Tales.** In this context, those contacted by the alien satellite from Albemuth become not just religious visionaries, but revolutionaries as well. Collectively known as "Aramchek," they become the victims of brutal political repression. The falsity of the distinction between politics and religion is a recurring theme in the story. Near the novel's end, the narrator (Philip K. Dick himself, albeit a fictional version thereof) discusses this idea in dialogue closely reproduced in the film:

There's also a strong emphasis placed on the novel's political message. It gives a sinister illustriation of an America gradually transforming into a police state that reminded me of Southland Tales.** In this context, those contacted by the alien satellite from Albemuth become not just religious visionaries, but revolutionaries as well. Collectively known as "Aramchek," they become the victims of brutal political repression. The falsity of the distinction between politics and religion is a recurring theme in the story. Near the novel's end, the narrator (Philip K. Dick himself, albeit a fictional version thereof) discusses this idea in dialogue closely reproduced in the film:

"[Aramchek believes] that we shouldn't give our loyalty to human rulers. That there is a supreme father in the sky, above the stars, who guides us. Our loyalty should be to him and him alone."

"That's not a political idea," Leon said with disgust. "I thought Aramcheck was a political organization, subversive."

"It is."

"But that's a religious idea. That's the basis of religion. They have been talking about that for five thousand years."

I had to admit that he was right. "Well," I said, "that's Aramchek, an organization guided by the supreme heavenly father."

This political theology-- in essence, a form of Christian anarchism-- is at the heart of Radio Free Albemuth, and the film highlights these concepts brilliantly. That's an element that was significantly diluted in the transition from Albemuth to Valis: bringing the story out of an alternate-universe police state and into something more closely resembling the real world reduces the urgency of this political theology. Simon also holds the film rights to Valis, which goes further down the theological rabbit hole, and has written a screenplay for Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said, which depicts a particularly unpleasant police state. In this context, Radio Free Albemuth may end up occupying the central territory in a sort of trilogy exploring the breadth of Dick's philosophy and theology. The film is currently in search of a distributor, but when it becomes more widely available, it's definitely worth seeking out.

Fore more on Radio Free Albemuth, see the film's official website and the Wall Street Journal's coverage of the premiere.

*Admittedly an overlooked masterpiece in its own right, and an excellent fusion of SF and theology.

**I should probably note that I mean this comparison as a compliment, since not everyone is kindly disposed to that film. See also my comparison of Sunshine to Event Horizon.

SF Gospel

- Gabriel Mckee's profile

- 21 followers