David M. Schwartz's Blog, page 2

June 30, 2011

Lightweight Summertime Musings

Deer Mom and Dad…. whoops, wrong musing. That was my letter from camp when I was seven years old, in which I described my excitement at catching a "forg" in the pond.

This summer, just a few years after that incident, my summertime musings begin by recalling my final school visit tour of 2010-11, which took place in late May in rural Gallia County, Ohio. It's in southeastern Ohio, near the charming small city of Gallipolis (pronounced nothing like Gallipoli, the peninsula in Turkey, but more like "Galley-Police"). This part of Ohio is in Appalachia, across the river from West Virginia, and just as scenic. Economically similar as well, I believe. I hadn't realized Appalachia extends into Ohio.

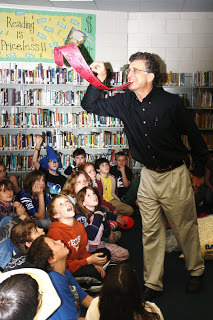

Here's a picture taken by my host, Leanna Martin of Addaville Elementary School, who organized my four days in the county schools. Can you tell that I'm demonstrating the principles of proportion? I've got a "tongue" that is half as long as my body, just as the tongues of many chameleon species are half the length of their bodies. (Those are the laggards of the chameleon world. Some species flick out tongues that are three times their body length. Their doctors must regret ever asking them to stick out their tongues for tonsil inspection.)

Anyway, I had a great time with the kids of rural schools in Gallia County. I loved watching them laughing at my math antics and getting all excited about my bags of popcorn that grow in size by powers of ten. Which is pretty much the same reaction I get from kids at suburban schools and urban schools. From white kids, black kids, brown kids. From rich kids, poor kids, in-between kids.

The great thing is that when you give them a chance, kids will be kids in more or less the same way. They find the same things funny, the same things suspenseful and the same things fascinating. There is a variation in taste, of course, but the vast majority will react in more or less the same way to the same stimuli. I'm not sure that's as true with adults. And it's the same with non-fiction books. Kids are curious about their world. They find fascinating facts to be…well, fascinating. Most adults have narrower focus. They're interested in sports…or science…or finance…or politics…or cooking…or children…or home improvements … I'm not saying they can't have multiple interests but I think kids have a more voracious and undiscriminating palate for the wonders of life. Which sounds delicious to me. Here is a picture of kids in counting to a million by piling up ten imaginary bags of one hundred thousand popcorn kernels. "… seven hundred thousand … eight hundred thousand … nine hundred thousand … ONE MILLION!!!"

OK, here's another summer musing. My deer mom sent me this link.

OK, here's another summer musing. My deer mom sent me this link.

It takes you to a blog about Egypt with a fascinating math-related post about the origins of the shapes of numbers — why Arabic numerals (the kind we all use) look the way they do. The answer: you've got to know the angles. The thesis is surprising and delightful. Is it true? I have no idea. I didn't do the research to check it. Hey, it's summertime! (I do have to wonder, though, if the numeral 9 ever really looked like that.

If you teach K-12, you're probably on vacation now, but that doesn't mean you're necessarily on vacation from discussions about education. Certainly the news media isn't on vacation from discussing (and often distorting) the subject and our politicians aren't on vacation from cutting school budgets and the bloviators aren't on vacation from spreading myths about teachers, students, schools and test scores. So here's a handy "talking-points guide" that you can carry around in your hip pocket if you like. It's part of the semi-weekly "Five Myths" series in the Washington Post that is intended to get you to take a second look at what you think you know. As Will Rogers said, "It isn't what we don't know that gives us trouble. It's what we know that ain't so." So to help in your discussions about education with those who know many things that ain't so, check out "Five Myths About America's Schools." I'll get you started:

Today's school reform movement conflates the motivations and agendas of politicians seeking reelection, religious figures looking to spread the faith and bureaucrats trying to save a dime. Despite an often earnest desire to help our nation's children, reformers have spread some fundamental misunderstandings about public education.

You can read all the myths here. I might carry on about my wish that author Paul Farhi had nodded to a sixth myth about school libraries in general and non-fiction literature in particular being disposable "extras" to education rather than one of its lead actors… but I won't.

Happy summer, everyone!

April 25, 2011

A Temple to the Glory of Knowledge and the Written Word

Two weeks ago, I spoke for three days at elementary schools in Fairfax County, Virginia, and for the next five days I played unabashed tourist in Washington, DC. It was Spring Break for many school districts and, as far as I could tell, 25% of the nation's school children were spending the week in the nation's capital. Museums, monuments and other federal buildings were bursting at the pilasters. In some cases, queues for limited admission tickets began at 6:30 am. As a result I didn't even cross the porticos of many of the sights on my list. Just the same, my visit had a clear highlight and I cannot imagine any other attraction having surpassed it.

I refer to our nation's temple of learning, dedicated to the glorification of knowledge and exaltation of the printed word. I refer to the Library of Congress.

The LOC's main building, now called the Jefferson Building, is an Italian Renaissance masterpiece, a celebration of learning, nationalism and the spirit of confidence and optimism that defined the United States at the turn of the 20th Century. To quote from a page on art and architecture in the LOC's extensive website, "Few structures represent human aspiration in such dramatic fashion." Compare the following anecdote with the political and financial climate of today: in 1886, architects presented Congress with two sets of plans for a library building — an adequate one with a projected cost of $4 million and an elaborate one with a price tag of $6 million. Congress opted to spend $6 million. And this: the construction engineers managed to build it for less than the allocated sum, leaving substantial funds for "artistic enhancement." The result is a highly decorated cultural monument featuring sculpture, mural painting and architecture unsurpassed in any public building in America. And all of it devoted to the glory of…books. (OK, not just books but other cataloged items that include recordings, photos and maps.)

When I decided to write my post on this remarkable institution, the world's largest library, I first thought I would delve into the numbers, my usual stock in trade: the 32 million books, which are but a fraction of the 142 million cataloged items … the 22,000 items received daily, of which 10,000 are added to the collection (what kind of recycling bin receives the other 12,000?) … the 650 miles of shelving … the staff of 3,600 … the 1.7 million visitors per year (few of whom exercise their right to access the collection, available to anyone 15 years or age or older). Instead I have decided to share some of the quotations inscribed in stone in the four corridors on the second floor of the Great Hall. Blown away by the overall effect of the building and entranced by the plethora of details, I found myself returning time and again to those quotations. Their sources are not given, lending an air of secular "gospel."

What follows are my favorites, without punctuation edits (though I am tempted) and with brief commentaries to which I invite you to add your own by commenting on this post.

BOOKS MUST FOLLOW SCIENCES

AND NOT SCIENCES BOOKS

Does this bring "creation science" to mind? Global warming denialism? Astrology and other pseudosciences?

IN BOOKS LIVES THE SOUL OF THE

WHOLE PAST TIME

Note that it says "the soul," not merely "the record." The difference is profound and, I imagine, the word choice was not accidental.

WISDOM IS THE PRINCIPAL THING

THEREFORE GET WISDOM AND WITH ALL

THY GETTING GET UNDERSTANDING

So it's not just the stuffing in of facts, but the understanding that counts! Do you see any parallel to the dichotomy between the reading of textbooks (chockablock with disembodied facts) vs. quality non-fiction literature (facts in the service of understanding)?

KNOWLEDGE COMES BUT WISDOM LINGERS

The ultimate goal, again, is not merely a gluttony of facts, but what happens when they are processed into wisdom. A comforting thought.

IGNORANCE IS THE CURSE OF GOD

KNOWLEDGE THE WING

WHEREWITH WE FLY TO HEAVEN

Even in this secular temple we find theological themes like this, but notice how the author identifies the flight path to Heaven.

THERE IS ONLY ONE GOOD NAMELY KNOWLEDGE

AND ONLY ONE EVIL NAMELY IGNORANCE

Another aphorism with theological undertones but secular overtones.

GLORY IS ACQUIRED BY VIRTUE

BUT PRESERVED BY LETTERS

A high-fallutin' paen to books. And as a tribute to those who write them, we have…

THE CHIEF GLORY OF EVERY PEOPLE

ARISES FROM ITS AUTHORS

How can I but adore this one? Finally…

THE FOUNDATION OF EVERY STATE

IS THE EDUCATION OF ITS YOUTH

I can add nothing to that. I just hope that some members of the august body for whose education this institution was principally intended (and whose name it bears) will wander over here to take note. . . and instead of political lip-service to education, they will literally put their money where their mouth is in a fashion as generous as that of their 19th Century forbears who chose the high road in funding this truly magnificent building.

March 28, 2011

What If

Esteemed non-fiction author Elizabeth Partridge recently wrote in her blog, Hot Tea and a Pencil, that she had just learned about an ancestor of the same name as herself who, in 1846, had been transported from England to Australia.

Contemporary Elizabeth asked,

"What did this Elizabeth Partridge do that got her ten years in jail, swapped off for being sent to Australia? What was it like for her once she got there?"

What if….

and a seed is planted. I don't know that I would ever take this any further, but it is exhilarating to have my mind tumble in a new direction.

What kind of random things have been making you think 'What if….?'"

Here is what I wrote as a comment:

Hi Elizabeth,

Since you asked what kinds of things make my mind ask, "What if?" I'll say that many of my own science and math picture books are based on "What if?" questions that I asked, going back to childhood:

"What if I could ride my bike to the Sun — how long would it take?"

"How about if I rode to the distant stars?"

"What if I could ride to the end of the Universe? What would I find there? Would there be a wall with a sign: "END OF UNIVERSE–DO NOT GO BEYOND THIS POINT"? (I really do remember imagining that sign, not because I really thought it could exist but as a way of expressing the mind-boggled feeling I got from contemplating the idea of a finite universe.)

"What if I could hop like a frog? How far could I go in proportion to my own body size?"

"What if someone filled an Olympic-size swimming pool with ice cream and I dived in–how long would it take me to eat my way through the pool?"

"If I grew to the height of a redwood tree, how high would a basketball hoop be if it elevated proportionally?"

And so on. In various ways, these musings ended up becoming books.

When I visit schools, the kids' top three questions are:

1) How old are you? (Teachers always say, "No, don't ask that question!")

2) How much money do you make? (Teachers say, "No, no! Never ask that question!")

and

3) Where do you get your ideas? (Teachers say, "That's a good question!")

I answer the first question by telling them what year I was born. (I don't mind if they know how old I am. How else will they learn what a 59-year old looks like compared to a 29-year old?) I answer the second question by telling them how much (little) I make on the sale of one book. And I answer the third question by telling children I get many of the ideas for my books from questions I asked when I was their age, and that they will get plenty of great ideas themselves if they wonder about the world. In other words, if they ask questions like, "What if?"

I also point out that I wrote about my love for the word "if" in my math alphabet book, G Is for Googol, under the letter "I" which, in my book, is for "If." With the word "if," I tell readers, you can imagine anything and sometimes you can use math to figure out what would happen if it were true.

I think parents and teachers (not to mention media providers) would do children and our future a great service if they encouraged wondering and the asking of questions rather than simply consuming and accepting information and stimuli. Children need to interact, not just imbibe, what the world sends their way. Our idea of interactivity has come to mean playing games invented by someone else rather than making our own observations, asking our own questions and finding answers through experiments (whether physical experiments or thought-experiments or both).

Case in point: I once met a 6th grade science teacher who had asked her students in a well-heeled public school to put some small piece of the natural world (a few plants and/or small animals) and temporarily transfer it to a contained environment (shoebox, glass jar, etc.) for an hour of observing, speculating, hypothesizing and experimenting. Everyone in the class thought the assignment was too hard. They didn't know what to do for an hour. The teacher lamented that if she had asked them to write a 10-page report on Einstein, no one would have batted an eye.

You might say the whole class — or a whole generation — has a "what if?" deficit.

What if we started a nationwide discussion on what to do about it? My two cents: more wondering, not more testing.

January 24, 2011

Saving Lives — and Math Education — With Statistics

Once again, a child at a school assembly asked me where I get my ideas. As usual, I said ideas are everywhere. This month I've been getting ideas from the newspaper, particularly coverage of the Tucson tragedy. It's given me the idea that it's high time to write a book that will go some small way to make our country a better place for people's lives, not just a better place for people's math. In fact, I'm thinking of a book that can do both because they just might be related.

Once again, a child at a school assembly asked me where I get my ideas. As usual, I said ideas are everywhere. This month I've been getting ideas from the newspaper, particularly coverage of the Tucson tragedy. It's given me the idea that it's high time to write a book that will go some small way to make our country a better place for people's lives, not just a better place for people's math. In fact, I'm thinking of a book that can do both because they just might be related.

We live in an era and a society where dogma trumps evidence and the drama of one trumps the experiences of many. The tendency to generalize from single examples seems to take over the minds of those (and there are many) unwilling or unable to recognize the relative insignificance of the examples they flourish. Show a gun-rights supporter statistics demonstrating unambiguously that families with guns in their homes are far more likely to suffer an injury or death from gunshot … and they'll come back with an anecdote about one exceedingly rare instance where someone defended his family with a gun. Talk about Columbine or Virginia Tech or Tucson and they'll tell you an apocryphal story about the arms-bearing citizen who stopped a potential shooting.

Statistics let us distinguish data from anecdote. Maybe some day (how's this for wishful thinking?) a society that is statistically literate will create laws that actually help protect people from madmen instead of absurdly lax laws that protect the madmen until it's too late to stop them.

And we need to understand probability. If you tell a gun supporter that we need better background checks on gun purchasers, she might point out that the checks are no better than 50% effective. But if prospective purchasers have to go through three successive screens, nearly 90% of the mad shooters would be stopped. One more screen and you're up to almost 95%. It's in the math.

And we need to understand probability. If you tell a gun supporter that we need better background checks on gun purchasers, she might point out that the checks are no better than 50% effective. But if prospective purchasers have to go through three successive screens, nearly 90% of the mad shooters would be stopped. One more screen and you're up to almost 95%. It's in the math.

Would quality children's books on statistics and probability make any difference in our laws or attitudes? I don't know but can we afford to wait any longer to find out? Let's see… if 10% of the people had a better mathematical basis for interpreting the information and misinformation that bombards us daily, and if each of them told 10 people who told 10 people…

One of my math heroes is Dr. Arthur Benjamin, a math professor at Harvey Mudd College, and a world-renowned "math magician" who astonishes audiences with amazing mental math calculations that he can do faster than any of the eight volunteers who come to the stage with their calculators. Prof. Benjamin did a short Ted talk about his formula for changing math education in America. You can find it on the TED webiste. It's only three minutes long and it might change your view of math education which, Benjamin believes, is on the wrong trajectory.

In every school system in America, math starts with counting and arithmetic, goes through algebra, aiming squarely for calculus. The genius of calculus and its importance to physicists and engineers is not to be denied, says Benjamin, but the vast majority of us will never use it. Instead they get lost and disillusioned with mathematics long before they face their first derivative. Benjamin believes that math education should point math users towards probability and statistics instead of calculus. You'll use your understanding of statistics and probability every day, whether you're a physicist or a farmer, whether you work in a factory or in front of a computer monitor (or both). And, I hope, you'll use it when you read the newspaper.

October 25, 2010

Are Picture Books Dead?

UPDATE: One of the commenters on this post pointed out that Amanda Gignac was badly misquoted, or quoted out of context, by the New York Times in the article I refer to. Apparently, her misquote has been perpetuated widely on the internet and I am one of the perpetuators. I hereby offer my apology to Ms. Gignac and I will delete two somewhat sarcastic remarks I made in the original version of this post. Her account of what happened and her commentary, can be found on her book blog, The Zen Leaf, and I urge you to read it.

Despite the unfortunate aspects of this kerfuffle (Ms. Gignac's appropriate word for it), and without meaning disrespect singled out at any individual, it does remain the case that the push for higher test scores and faster achievement in reading has taken a toll on the attitude toward picture books held by many schools, parents and even children. Many of us find that to be a disturbing and counterproductive trend.

–David

Did you see the obituary for picture books that appeared earlier this month in the New York Times?

The title of the article is "Picture Books No Longer a Staple for Children" but that title understates the purported demise of the picture book. Not only are sales way down and shelf space in bookstores vastly diminished, not only are publishers cutting way back on the number of picture books they're willing to publish each year, but parents are forbidding their children to even peek at the nasty things. That's right, there are parents out there — plenty of them — who seem to think that picture books are hazardous to their child's intellectual health. For example, we get to meet Amanda Gignac, who writes a book blog, and whose son started reading chapter books at 4. At 6 1/2, Laurence is forbidden to regress in his reading. "He would still read picture books now if we let him," says the boy's mom. But, according to the New York Times, both parents are firm in their mission to allow only chapter book. But wait a minute… there is one other thing we get to learn about this boy from his mother: "He is still a 'reluctant reader.'"

Well, in their comments, readers of this article excoriated the attitude held by parents such as the Gignacs. I had expected people to pay tribute to some of the unforgettable picture book characters that we all know and love, characters we would hate to have grown up without. But most of the comments focused on the benefits of the pictures in picture books, how they aid in the intellectual and emotional development of children, how they open up worlds of imagination and thought, and how a childhood without them would be an impoverished childhood.

I have no disagreement with any of those sentiments. But for a moment let's forget about the splendid illustrations and beloved fictional characters we'd have to kiss good-bye in a world without picture books, and let's mourn the loss of non-fiction picture books. Not the illustrations and photographs — magnificent as they often are — but the concepts and text. Let's imagine a young child like Laurence Gignac totally deprived of them. Here's what I want to know: If he were limited to non-fiction literature outside the picture book section of his local library or bookstore, if he shunned all those big, thin books with pictures in addition to words on every page, would his intellectual capacities develop more rapidly or less rapidly? Comparing the picture book world of non-fiction with the low- or no-picture book world, is the only difference in the reading level? Or is something else missing in that picture-less world?

Here is where I want your help. I think we should compile a running list of non-fiction picture books that have no counterpart whatsoever in the other, more "grown-up," world of chapter books. My hunch is that for every author of this blog, there are oodles, and the same for the zillions of other excellent books by other excellent authors. I'll get you started with one of my own, and then it's going to be your turn.

I might as well pick my first book, How Much Is a Million? It's celebrating its 25th anniversary this year and it's still going strong in both hardcover and paperback (and in a number of languages). I guess somebody must be reading it! The book offers mind-bending ways to picture the numbers one million, one billion and one trillion and gives the reader concrete ways to wrap their minds around the difference in magnitude between those three oft-used but poorly-understood big numbers. For example, if you counted non-stop from one to one million, it would take you about 23 days … if you counted non-stop to a billion it would take about 95 years … and to a trillion you'd be at it for 200,000 years! Big diff, eh?

Can anyone show me a chapter book that would lead precocious children to a better understanding of what happens to a number when you put three zeros after it? Does such a book exist? If so, I haven't seen it. Interestingly, since my book came out, a few other authors have tackled similar material in fascinating, original ways. But they're all picture books.

So how about if each reader of this blog (including but not limited to the authors of this blog, who need not be shy about pushing their own books) chimes in with just one example of a non-fiction picture that contributes to the education of its readers in a unique way that has no parallel in the world of more advanced chapter books. We'll put together a list, just to keep track of what humankind will be missing if the portentous trend described in the New York Times continues. We may not have any new picture books, but least we'll have our list!

September 27, 2010

Speaking to the Test

I think I did pretty well, but I'm not sure.

Several teachers told me that the presentations I had just given were the best they had ever seen. One said it was inspiring to her students and herself. Another said she didn't want me to stop because the kids were learning so much. A third said I was explaining difficult concepts in ways she had never thought of, and the kids were getting it — and having fun to boot!

But the only evaluation that "counts" will be the one that comes in after the tests are graded. Yes, the Big Brother of testing is now watching over authors who speak at schools. I spent three days giving author presentations in central California, funded by a special state program for the children of migrant agricultural workers. It was explained to me that the state requires the children to be tested before and after the presentation so their learning (i.e., my teaching) can be assessed. It was a new experience for me. I had to write a test for each grade level, to be administered both before and after my presentations. Improved scores would be the ticket.

Sounds logical, doesn't it? Sounds simple, right? Wrong! What an awakening it was for me to see firsthand what testing does to teaching. Teachers have to cope with this every day so, if nothing else, at least I could get a feel for their daily reality. And they don't have the opportunity to write to the test.

I'm glad the kids had fun and they learned something but that's only because I got to do what teachers never have the luxury of doing: I ignored the tests. After writing them, I thought about how I could boost scores. I came up with many ways, but I realized a something that teachers have known for years: testing trumps teaching. (For another blog post on the subject of testing, see Vicki Cobb's superb, thought-provoking I.N.K. piece on September 10th.) Here's what I would have done if my main object had been to raise test scores:

speak to the test — The test is what counts so ignore all else! If a wonderfully teachable moment comes along and it's not on the test, forget it. I use popcorn as a prop to explain big numbers and to show, visually, what happens every time you put a zero after a number. If, as often happens, a child asks, "Did you count all that popcorn?" I should ignore the question and go on. Never mind that it's the perfect opportunity to talk about estimation — an important concept often misunderstood by both teachers and children. Estimation is not on the test. Forget it.

pretend all children learn in the same way — There's no time to approach the same subject from different angles in order to reach different kinds of learners. Just get the info out there so they will learn it. Pound it into them. I talk about proportions using the example of a three inch frog hopping 20 feet. "How good of a hopper is that frog for its size?" I ask. In other words, how many of its own size does it hop? There are many ways to approach such a question but there is only time for one approach. To make sure that one gets through…

repeat, repeat, repeat — If I know I'm making a point that is on the test, I'd better say it three, four, ten times. Then maybe they'll all hear it and remember it. Repeating the same fact or the same approach over and over again takes less time than starting the whole problem over in a different way to accommodate different learning styles.

forget about the love – Just go for the facts. There is no need to talk about a love of learning or books or, in my case, math and science — and how my passion for them goes back to my childhood. That's not testable. There is no sense in trying to get my audience to wonder about the world around them ("Wondering is wonderful," I like to say as I show them how my books go back to my childhood musings), but what good is that when it can't be tested?

throw spontaneity out the window — Normally, I try to read my audience, as a teacher must read her/his class, and respond appropriately. My presentations are not a "speech" that I read aloud or recite from memory. They go in different directions based on the children's responses to what I have already done, and where they inspire me to go next. But with a test lurking in the background, spontaneity will not do! I must go to the same place every time because the test questions are fixed.

Before I got to the schools last week, I thought about all the changes I would have to make to my presentation in order to maximize test scores. And then I decided not to make any of those changes. I decided I'd rather inspire the kids and give them a good time, let them associate math and science with fascination and fun instead of dullness and drudgery. So I gave the presentation I wanted to give. And they loved it, as did their teachers.

When the test scores come in, I'll find out if it was any good.

June 28, 2010

Goodbye, Mr.Gardner

A few years ago, after I finished a presentation at an elementary school in Norman, Oklahoma, a boy came up to tell me that his great grandpa also liked to make math fun. "Who's your great grandpa?" I asked. "Martin Gardner," he said.

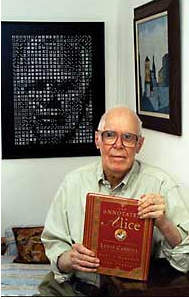

Martin Gardner! He might as well have told me that his great grandpa was God. No doubt about it, Martin Gardner, creator of the witty and mind-bending "Mathematical Games" column that ran for 24 years in Scientific American, could be called the God of recreational math. And Gardner was more than that. He wrote more than 70 books on subjects as diverse as philosophy, magic and literature — The Annotated Alice, his definitive guide to Lewis Carroll's classic, was perhaps his best selling title. He was also a leading debunker of pseudoscience: after retiring from Sci Am, he sicked his penetrating logical powers on purveyors of quackery, ESP, UFOs and the like in a column called "Notes of a Fringe Watcher," published for 19 years in The Skeptical Inquirer.

Poet W.H. Auden, sci fi author Arthur C.Clarke, evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould and astronomer Carl Sagan were among his many admirers. Vladamir Nabokov named him in a novel. Astrophysicists named an asteroid after him.

Martin Gardner died last month at the age of 95. He had continued to write and publish until the last months of his life. His last article, on the pseudoscience of Oprah Winfrey, was published in March. But he will always be remembered most fondly as bringing math to millions. Of many tributes I have read, my favorite is from mathematician Ronald Graham: "He has turned thousands of children into mathematicians, and thousands of mathematicians into children."

It doesn't get any better than that.

When I read some of his obits, looking for impressive biographical material, I was surprised to find that Martin Gardner, despite his godly status, struggled to keep one step ahead of his readers. When Scientific American asked him to write a column on mathematical games, he hit the secondhand bookshops to find books about math puzzles. This became his m.o. for years as he attempted to meet his monthly deadline. "The number of puzzles I've invented you could count on your fingers," he told The New York Times.

Can you believe it? Martin Gardner, deity, scrambling to come up with the next mathematical game for his readers, and not always as original as we assumed. It reminds me of myself with this blog! Actually, it reminds me of myself with my books, and probably many other non-fiction authors with theirs. Students, teachers and librarians often seem to think we have a magical facility for turning the facts of the world into mellifluous, riveting prose, but actually we're just folks who get out there to do research, write and rewrite until we're blue in the face, and finally come up with something we're not too embarrassed to send to a waiting readership (and reviewership) — then we hold our collective breath in the hope that someone will like it. Martin Gardner, who never took a college class in mathematics (he graduated in philosophy from the University of Chicago), wrote of the research for his Sci Am columns, "It took me so long to understand what I was writing about, that I knew how to write about it so most readers would understand it." He took complex mathematical concepts and turned them into puzzles, explaining them clearly in playful, witty, inviting ways. According to Douglas Martin's obituary in The New York Times, Gardner said his talent was asking good questions and transmitting the answers clearly and crisply.

Isn't this the talent that all non-fiction authors strive to develop? For those as successful as Martin Gardner, it expresses itself effortlessly and abundantly. The rest of us it keep plugging away at it, as if it were a Martin Gardner puzzle.

May 24, 2010

Researching with Researchers

I always enjoy outdoor activities and meals with Tom and Ellen but I had an ulterior motive this time. Ellen, aka Prof. Simms, is a botanist in the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. I am writing a book on what happens to the jack-o' lantern after Halloween — a Halloween book for November, you might say. My ulterior motive is that I wanted Ellen's help in identifying some of the blotchy, fuzzy and moldy looking things growing on the pumpkin. Their portraits, captured by photographer Dwight Kuhn, were the perfect accompaniment to herb tea and ice cream.

I always enjoy outdoor activities and meals with Tom and Ellen but I had an ulterior motive this time. Ellen, aka Prof. Simms, is a botanist in the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. I am writing a book on what happens to the jack-o' lantern after Halloween — a Halloween book for November, you might say. My ulterior motive is that I wanted Ellen's help in identifying some of the blotchy, fuzzy and moldy looking things growing on the pumpkin. Their portraits, captured by photographer Dwight Kuhn, were the perfect accompaniment to herb tea and ice cream.

When people think of what it means for a non-fiction author to do research, they usually envision the author looking up facts in books or articles — either in print or online. For me research involves all of that, but most of all, I like to consult experts. Whether the subject is mathematics, music or mycology (or subjects that don't begin with "m"), I get the most bang for my research buck when I sit down and talk with someone who knows what he or she's talking about — if it is what I want to be writing about.

Before I started writing non-fiction book for children, I was a frequent contributor of articles to Smithsonian, National Wildlife and Audubon. Working with experts was not only essential to reporting a story, but it was more than half the fun. I spent two weeks in Tanzania with a biologist who studied communication in hippos. I went to far northern Scotland to track outlaw egg collectors with investigators from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. I spent time with wildlife biologists who were breeding river otters from Louisiana to reintroduce them to the species' former range in Missouri. What fine fun, what fine facts (and what a lot of frequent flyer miles)!

How does a writer find these mavens? It helps to have friends in universities but there are other ways. I have looked for the names of researchers quoted in books and articles. Usually that person's university or company is mentioned, so I just look her up and call. I don't always get a call back, but I'm onto my next lead and not worrying about. The internet can really help here. Just search any topic and follow a few of the links to find the names of experts galore. I look at their publications to see if they specialize in the subject of my own research.

Experts themselves are a little like websites: they usually "link" me to others. Before we had gotten past the first few pictures, Ellen had suggested I see a Berkeley colleague, mycologist Tom Bruns, in the Department of Plant and Microbial Biology. (Mycologists study fungi.) He doesn't know it, but at about the time you read this, I'll be looking up his phone number and getting ready to call.

April 26, 2010

To Be a Writer: Read, Read, Read. But…

Last week, I had the pleasure of working with Linda Sue Park and Ed Young at the American Embassy School of New Delhi, India. We were the featured authors at AES's annual Authors' Week. During one of our many dinners together, Linda Sue and I talked about the importance of reading children's books as a prerequisite to writing children's books. Linda Sue is a Newbury Award-winning novelist and picture book author. Although she is essentially a fiction writer, the crafts of writing fiction and non-fiction probably have more in common than they have differences, and the need for reading is surely a commonality.

Linda Sue has posted something about reading for writing on her website, www.lspark.com. I am traveling in India this week, checking email intermittently at internet cafes (and wondering why they call themselves cafes when they serve neither coffee nor tea nor anything else one can drink or eat). For this post — if I can squeeze it out before the power goes off again — I am going to quote this portion of Linda Sue's website, and then comment upon it briefly.

The Importance of Reading

Read. That's the single best thing an aspiring writer can do for his or her work. I once heard an editor say, "Read a thousand books of the genre you're interested in. THEN write yours."

I was astonished and pleased to hear her say this–because that's exactly what I did. During the years when I had no thought of writing for children (see About the Author), I read and read and read. Middle-grade novels. Hundreds of them–easily more than a thousand. Then I wrote mine–and it sold on its first submission. Luck? Coincidence? Maybe…but I doubt it.

My personal reading list draws from a wide variety of genres. I love middle-grade novels best, but I also read Young Adult novels and picture books. I read adult literary fiction, mysteries and nonfiction. I read poetry. I love books on food and travel. Whether a wondrous story or a hilarious passage of dialogue or a beautiful sentence or a memorable image, every bit of reading I do helps my own writing. The rhythm of language and the way words combine to communicate more than their dictionary meanings infuse the serious reader's mind and emerge transformed when that reader sits down to write.

That's really the best possible advice I could give any writer–read. But I find that folks are often disappointed with this advice, so I'll offer a few more basic tips.

Please do read Linda Sue's valuable tips (www.lspark.com/writing.html) but that's all I will quote here. I agree with absolutely everything she says on this subject and I would encourage any writer, whether previously published or not, to read extensively. But there is a "but." The "but" has to do with my own early experience as a writer. Question: How many children's books in the mathematical genre did I read before writing my first book, How Much Is a Million? Answer: none.

This is only in part because there weren't many back in the late 70′s and early 80′s when I was working on the disorganized morass of handwritten and typed pages that eventually coalesced into that book. Mainly it is because I didn't think of myself as a writer and I guess I didn't take my project seriously. I had no idea if what I was working on would ever become a book. I simply had an idea that went back to my childhood fascination with big numbers, and I wondered if I could turn it into something anyone would want to read. In writing it, I just went with my instincts.

Perhaps — though I'm not really sure– this had something to do with the content of the telephone call I eventually got telling my that my manuscript was going to be published. "It's so original," said Barbara Lalicki, senior editor at Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books. "We've seen plenty of number book manuscripts, but we've never seen one like this."

Original. Would my manuscript have been considered so original if I had read a thousand books before reading it? Maybe. Maybe not. I don't know but I have a hunch that my naivite had something to do with the ultimate product.

Yet I completey agree with Linda Sue. And here's an irony. In preparing to write the 50 books since that one, I have always read as extensively as I could. But is any of these books as original as my first one? I have no idea. Please feel free to weigh in with your two rupees. I have to sign off because they're about to close the internet cafe. Namaste.

March 14, 2010

Happy Pi Day

In case you missed it, March 14th was an important international holiday. Every year, math enthusiasts worldwide celebrate the date as Pi Day. March 14th. 3/14. 3.14. Pi. Get it? If you'd like a higher degree of accuracy, you can celebrate Pi Minute at 1:59 on that date (as in 3.14159). Or why not Pi Second at 26 seconds into the Pi Minute (3.1415926)?

"It's crazy! It's irrational!" crows the website of the Exploratorium, San Francisco's famously quirky hands-on science museum. The Exploratorium invented the holiday twenty-one years ago. In a delightful coincidence, Pi Day coincides with Albert Einstein's birthday. Exploratorium revelers circumambulate the "Pi Shrine" 3.14 times while singing Happy Birthday to Albert.

Pi Day celebrations have spread to schools. Just over a year ago, I visited Singapore American School to give a week's worth of presentations and I found parent volunteers serving pie to appreciative students whose math teachers were trying to sweeten their understanding of the world's most famous irrational number. Just as pi is endless, so is the list of activities, from memory challenges and problem solving to finding how pi is connected to hat size … and writing a new form of poetry called "pi-ku," which uses a 3-1-4 syllable pattern instead of haiku's 5-7-5.

It's Pi Day!

Learn

math's mysteries.

It is indeed the mysteriousness of pi that makes it so fascinating. For 3,500 years, according to David Blatner, author of The Joy of Pi, pi-lovers have tried to solve the "puzzle of pi" — calculating the exact ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter. But there is no such thing as "exact." No matter how successful, pi can only be estimated.

A refresher course for the pi-challenged: The 16th letter of the Greek alphabet, ? or "pi," is used to represent the number you get when you divide a circle's circumference (the distance around) by its diameter (distance across, through the center). Try it on any circle with a ruler and string and you'll get something a little over 3 1/8 or approximately 22/7 (some have therefore proposed the 22nd of July for Pi Day). Measured with a little more precision, the ratio comes out to 3.14. But don't stop there. Pi is an irrational number, meaning that, expressed as a decimal, its digits go on forever without a repeating pattern. Hence the obsession of some with memorizing pi to 100, even 1,000 places. As a Pi Day gift from 5th graders at a school I visited this year on March 15th, I received a sheet of paper with pi written out to 10,000 digits. In 2002, a computer scientist found 1.24 trillion digits. Never mind that astrophysicists calculating the size of galaxies don't seem to need an accuracy of pi any greater than 10 to 15 digits. Playing with pi offers endless hours of good, clean mathematical fun. So what if it's irrational.

Happy (belated) Pi Day, everybody!