Kittredge Cherry's Blog: Q Spirit, page 55

April 30, 2013

LGBT rights versus Christian faith: International Day Against Homophobia calls for prayers

Cartoon by Carlos Latuff

Cartoon by Carlos LatuffChristian and LGBT values clash in a new cartoon for the International Day Against Homophobia by Brazilian artist Carlos Latuff.

The International Day Against Homophobia (IDAHO) on May 17 raises awareness of LGBT rights violations around the world and supports a progressive vision of sexual and gender diversity. It includes a “multi-faith global prayer initiative.”

Freedom of religion and LGBT rights are often seen as opposites, as in Latuff’s illustration. LGBT Christians get caught in the middle, embodying both viewpoints.

In Latuff’s image, the lesbian in a rainbow shirt brandishes a transgender symbol while shielding herself with the Constitution (Constituição in Portuguese). The Christian uses the Bible as a shield while he waves a cross. I imagine that the lesbian is in touch with her spiritual power, the power of Christ who broke rules and crossed boundaries: touching lepers, reaching out to women, eating with prostitutes, talking to foreigners, being accused of blasphemy.

For more info about Latuff, see my previous post, Gay Christ wears rainbow flag in art by Latuff.

Latuff created this image specifically to promote Brazil’s National March Against Homophobia (Marcha Nacional Contra Homofobia), which will be held May 15 in Brasília. The twin towers in his cartoon are the government buildings in the Brazilian capital of Brasilia designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer.

_______

Copyright © Kittredge Cherry. All rights reserved.

http://www.jesusinlove.blogspot.com/

Jesus in Love Blog on LGBT spirituality and the arts

Published on April 30, 2013 12:18

April 27, 2013

Christina Rossetti: Queer writer of Christmas carols and lesbian poetry

Cover illustration for Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market and Other Poems” (1862) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti)

Portrait of Christina Rossetti

by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Christina Georgina Rossetti was a 19th-century English poet whose work ranged from Christmas carols to sensuous lesbian love poetry. A devout Christian who never married, she has been called a “queer virgin” and “gay mystic.” Her feast day is today (April 27) on the Episcopal and Church of England calendars.

Many consider her to be one of Britain’s greatest Victorian poets. Rossetti’s best-known works are the Christmas carol “In the Bleak Midwinter” and “Goblin Market,” a surprisingly erotic poem about the redemptive love between two sisters who overcome temptation by goblins. The imagery is unmistakable in verses such as these:

She cried, “...Did you miss me?

Come and kiss me.

Never mind my bruises,

Hug me, kiss me, suck my juices

Squeez’d from goblin fruits for you,

Goblin pulp and goblin dew.

Eat me, drink me, love me…”

She clung about her sister,

Kiss’d and kiss’d and kiss’d her…

She kiss’d and kiss’d her with a hungry mouth.

There is no direct evidence that Rossetti was sexually involved with another woman, but the imagery in her writing is unmistakable. Historian Rictor Norton reports that her brother destroyed her love poems addressed to women when he edited her poetry for publication. Rossetti is included in “Essential Gay Mystics

” by Andrew Harvey. A comprehensive chapter titled “Christina Rossetti: The Female Queer Virgin” appears in “Same Sex Desire in Victorian Religious Culture

” by Andrew Harvey. A comprehensive chapter titled “Christina Rossetti: The Female Queer Virgin” appears in “Same Sex Desire in Victorian Religious Culture ” by Frederick S. Roden. Rossetti is also important to feminist scholars who reclaimed her in the 1980s and 1990s as they sought women’s voices hidden in the church’s patriarchal past.

” by Frederick S. Roden. Rossetti is also important to feminist scholars who reclaimed her in the 1980s and 1990s as they sought women’s voices hidden in the church’s patriarchal past.Rossetti (Dec. 5, 1830 - Dec. 29, 1894) was born in London as the youngest child in an artistic family. Her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti became a famous Pre-Raphaelite poet and artist. Encouraged by her family, she began writing and dating her poems starting at age 12.

When Rossetti was 14 she started experiencing bouts of illness and depression and became deeply involved in the Anglo-Catholic Movement of the Church of England. The rest of her life would be shaped by prolonged illness and passionate religious devotion. She broke off marriage engagements with two different men on religious grounds. She stayed single, living with her mother and aunt for most of her life.

Christina posed

for this Annunciation

by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

During this period she served as the model for the Virgin Mary in a couple of her brother’s most famous paintings, including his 1850 vision of the Annunciation, “Ecce Ancilla Domini” (“Behold the Handmaid of God”)

Starting in 1859, Rossetti worked for 10 years as a volunteer at the St. Mary Magdalene “house of charity” in Highgate, a shelter for unwed mothers and former prostitutes run by Anglican nuns. Some suggest that “Goblin Market” was inspired by and/or written for the “fallen women” she met there.

“Goblin Market” was published in 1862, when Rossetti was 31. The poem is about Laura and Lizzie, two sisters who live alone together and share one bed. They sleep as a couple, in Rossetti’s vivid words:

Cheek to cheek and breast to breast

Lock’d together in one nest.

But “goblin men” tempt them with luscious forbidden fruit and Laura succumbs. After one night of indulgence she can no longer find the goblins and begins wasting away. Desperate to help here sister, Lizzie tries to buy fruit from the goblins, but they refuse and try to make her eat the fruit. She resists even when they attack and try to force the fruit into her mouth. Lizzie, drenched in fruit juice and pulp, returns home and invites Laura to lick the juices from her in the verses quoted earlier. The juicy kisses revive Laura and the two sisters go on to lead long lives as wives and mothers.

“Goblin Market” can be read as an innocent childhood nursery rhyme, a warning about the dangers of sexuality, a feminist critique of marriage or a Christian allegory. Lizzie becomes a Christ figure who sacrifices to save her sister from sin and gives life with her Eucharistic invitation to “Eat me, drink me, love me…” The two sisters of “Goblin Market” are often interpreted as lesbian lovers, which means that Lizzie can justifiably be interpreted as a lesbian Christ.

In 1872 Rossetti was diagnosed with Graves Disease, an auto-immune thyroid disorder, which caused her to spend her last 15 years as a recluse in her home. She died of cancer on Dec. 29, 1894 at age 64.

She wrote the words to “In the Bleak Midwinter” in 1872 in response to a request from Scribner’s Magazine for a Christmas poem. It was published posthumously in 1904 and became a popular carol after composer Gustav Holst set it to music in 1906. Her poem “Love Came Down at Christmas” (1885) is also a well known carol, but “In the Bleak Midwinter” continues to be sung in churches, by choirs, and on recordings by artists such as Julie Andrews (video below), Sarah McLaughlin, Loreena McKennitt and James Taylor. The haunting song includes these verses:

In the bleak mid-winter

Frosty wind made moan,

Earth stood hard as iron,

Water like a stone;

Snow had fallen, snow on snow,

Snow on snow,

In the bleak mid-winter

Long ago.

Our God, Heaven cannot hold Him

Nor earth sustain;

Heaven and earth shall flee away

When He comes to reign:

In the bleak mid-winter

A stable-place sufficed

The Lord God Almighty,

Jesus Christ....

What can I give Him,

Poor as I am?

If I were a shepherd

I would bring a lamb,

If I were a wise man

I would do my part,

Yet what I can I give Him,

Give my heart.

The Episcopal Church devotes a feast day to Christina Rossetti on April 27 with this official prayer:

O God, whom heaven cannot hold, you inspired Christina Rossetti to express the mystery of the Incarnation through her poems: Help us to follow her example in giving our hearts to Christ, who is love; and who is alive and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, in glory everlasting. Amen.

Rossetti herself may well have felt ambivalent about being honored by the church and outed as a queer. She shared her own thoughts for posterity in her poem “When I am dead, my dearest” (1862):

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

___

Related links:

Goblin Market (complete text)

In the Bleak Midwinter lyrics

Love Came Down at Christmas lyrics

Christina Rossetti profile (glbtq.com)

Christina Rossetti's Amazon.com page

____

This post is part of the GLBT Saints series by Kittredge Cherry at the Jesus in Love Blog. Saints, martyrs, mystics, prophets, witnesses, heroes, holy people, deities and religious figures of special interest to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) and queer people and our allies are covered on appropriate dates throughout the year.

Published on April 27, 2013 09:32

April 24, 2013

Jesus Appears to His Friends (Gay Passion of Christ series)

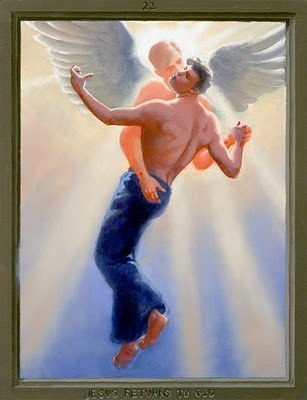

21. Jesus Appears to His Friends (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard (Collection of Bill Carpenter)

21. Jesus Appears to His Friends (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard (Collection of Bill Carpenter)“See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself; handle me, and see.” -- Luke 24:39 (RSV)

Friends react with joy -- and some doubt -- to the return of the risen Christ in “Jesus Appears to His Friends” from “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a series of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard. Jesus allows himself to be embraced and examined by his diverse friendship group. He gets hugs from his Beloved Disciple and an elderly woman with a cane. Smiling beside them is a young black woman, apparently Mary Magdalene. Meanwhile a bald skeptic in a suit inspects his wounded wrist. Other disciples watch from behind. The red gash in Jesus’ side stands out against his manly physique.

Jesus has been to hell and back. He’s managed to return to the land of the living. The same room and some of the same people are pictured in Blanchard’s Last Supper, but here the mood is transformed from a dark-toned goodbye to a happy hello, lit up with lavender and with warm flesh tones. Misty moonlight pours in from the back window in the shape of an ascending dove, hinting at the presence of the Holy Spirit.

Everyone else in Blanchard’s painting is delighted to see Jesus, while the bald Doubting Thomas figure in the tie and glasses is busy fact-checking. Jesus affirms the believers, but doesn’t push away the pragmatist. He is welcome to check the wounds scientifically. Thomas provides a positive role model as someone who tries to engage religion without falling for any mystical trickery. Many people, queer or otherwise, share the skeptic’s desire to develop a belief system based on direct experience and not get caught up in all the hoopla about Jesus.

The Bibles offers differing accounts of Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances to his friends. Taken as a whole, the gospels describe how the disciples were hiding from authorities behind closed doors when Jesus “came and stood among them.” He calmed their fears and breathed the Holy Spirit upon them. One disciple, Thomas, had rejected earlier reports that Jesus was still alive. “Unless I see in his hands the print of the nails, and place my finger in the mark of the nails, and place my hand in his side, I will not believe,” [John 20:25 RSV] he insisted. His doubt turned to faith when Jesus invited him to do just that.

As usual in the gay Passion series, Jesus attracts a surprisingly varied group. The imagery and title emphasize that the people around Jesus were not just his followers. They were his friends. As he told them at the Last Supper, “I have called you friends, for all that I have heard from God I have made known to you.” (John 15:15 Inc Lang Lect) It was the focus on friendship that led Bill Carpenter to acquire this particular painting when Blanchard’s gay Passion series was displayed at the 2007 National Festival of Progressive Spiritual Art in Taos, New Mexico.

Carpenter is one of the leaders of Soulforce, a civil-rights group that works to free LGBT people from religious and political oppression. He went to Taos to teach nonviolent resistance in preparation for anti-LGBT attacks, which fortunately did not materialize. “I chose ‘Jesus Appears To His Friends’ because, through it, I connected with the humanity of Jesus…He had friends! And, because Doug showed Jesus’ friends as a beautifully diverse collection of humanity…just like our world…and I felt that Jesus truly welcomed each and every soul into his world…with no qualification or judgment and I wanted to be reminded of that potential within me,” Carpenter said.

The painting fits into the long artistic tradition of Doubting Thomas, a common subject at least since the sixth century. Perhaps the most famous version was painted in 1602 by Italian artist Caravaggio with unflinching realism and street people as models. Artists mostly stopped portraying the Doubting Thomas scene after the Baroque period ended in the 18th century, even though his skepticism sums up the spirit of the modern era. Blanchard contributes to the standard repertoire of Doubting Thomas iconography by putting him in a larger vision of equality where same-sex love has an honored place. Another contemporary gay version was done by Spanish photographer Fernando Bayona Gonzalez. He accentuates the homoeroticism of Thomas touching the wound in Jesus’ side in his 2009 “Circus Christi” series.

“Jesus Appears of His Friends” affirms themes of vital importance to the LGBT community: Friendship, because many have been cut of from their biological families. Touch, because touching someone of the same gender has been taboo. And doubt, because religion has been used to justify violence against LGBT people. Crossing the boundary from death to life, Jesus touches those who live in the borderlands between male and female, between doubt and faith.

“The doors were shut, but Jesus came and stood among them, and said, ‘Peace be with you.’” -- John 20:26 (RSV)

Jesus’ friends were hiding together, afraid of the authorities who killed their beloved teacher. The doors were shut, but somehow Jesus got inside and stood among them. They couldn’t believe it! He urged them to touch him, and even invited them to inspect the wounds from his crucifixion. As they felt his warm skin, their doubts and fears turned into joy. Jesus liked touch. He often touched people in order to heal them, and he let people touch him. He defied taboos and allowed himself to be touched by women and people with diseases. He understood human sexuality, befriending prostitutes and other sexual outcasts. LGBT sometimes hide themselves in closets of shame, but Jesus wasn’t like that. He was pleased with own human body, even after it was wounded.

Jesus, can I really touch you?

___

This is part of a series based on “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a set of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard, with text by Kittredge Cherry. For the whole series, click here.

Scripture quotations are from Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, and 1971 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Published on April 24, 2013 13:35

April 17, 2013

Sor Juana de la Cruz: Nun who loved a countess in 17th-century Mexico City

Sor Juana Inés de la CruzBy Lewis Williams, SFO trinitystores.com

Sor Juana Inés de la CruzBy Lewis Williams, SFO trinitystores.com Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was a 17th-century Mexican nun whose critically acclaimed writings include lesbian love poetry. She is considered one of the greatest Latin American poets, an early advocate of women’s rights, and some say, North America's first lesbian feminist writer. Her feast day is today (April 17).

Production begins this summer on a film based on “Sor Juana’s Second Dream

,” a novel in which author Alicia Gaspar de Alba explores Sor Juana's romance with a Mexican countess.

,” a novel in which author Alicia Gaspar de Alba explores Sor Juana's romance with a Mexican countess.Sor Juana (Nov. 12, 1648 - April 17, 1695) was born out of wedlock near Mexico City in what was then New Spain. She was a witty, intellectually gifted girl who loved learning. Girls of her time were rarely educated, but she learned to read in her grandfather’s book-filled house.

When she was 16, she asked for her parents’ permission to disguise herself as a male student in order to attend university, which did not accept women. They refused, and instead she entered the convent in 1667. In her world, the convent was the only place where a woman could pursue education.

Sor Juana’s convent cell became Mexico City’s intellectual hub. Instead of an ascetic room, Sor Juana had a suite that was like a modern apartment. Her library contained an estimated 4,000 books, the largest collection in Mexico. The following portrait from 1750 shows her in her amazing library, surrounded by her many books.

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera, 1750 (Wikimedia Commons)

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera, 1750 (Wikimedia Commons)She turned her nun’s quarters into a salon, visited by the city’s intellectual elite. Among them was Countess Maria Luisa de Paredes, vicereine of Mexico. The two women became passionate friends. It’s unclear whether they were lesbians by today’s definition, but Maria Luisa inspired Sor Juana to write amorous love poems, such as:

That you’re a woman far away

is no hindrance to my love:

for the soul, as you well know,

distance and sex don’t count.

Click here for more of Sor Juana’s lesbian poems in English and Spanish.

The romance between Sor Juana and Maria Luisa continues to be an inspiration for contemporary writers and film makers. Poet and Chicano studies scholar Alicia Gaspar de Alba writes about it vividly in her novel “Sor Juana’s Second Dream

.” The novel became the basis for the play “The Nun and the Countess” by Odalys Nanín.

.” The novel became the basis for the play “The Nun and the Countess” by Odalys Nanín.Production begins this summer on a movie based on Gaspar de Alba's novel. Mexican actress Ana de La Reguera will play Sor Juana in "Juana de Asbaje," the film adaptation of Gaspar de Alba’s novel. She co-wrote the screenplay with the film's director, Rene Bueno.

Church authorities cracked down on Sor Juana, not because of her lesbian poetry, but for “La Respuesta,” her classic defense of women’s rights in response to opposition from the clergy. Threatened by the Inquisition, Sor Juana was silenced for the final three years of her life. At age 46, she died after taking care of her sisters in an outbreak of plague.

She is not recognized as a saint by the male-dominated church hierarchy that she criticized, but Sor Juana holds a place in the informal communion of saints honored by lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people of faith and our allies. She is especially revered as a role model by Latina feminists.

The icon at the top was painted by Colorado artist Lewis Williams of the Secular Franciscan Order (SFO). Sor Juana sits between Mexico City’s two volcanoes, the male Popocatépetl and the female Iztaccíhuatl, symbolizing the conflict between men and women that she experienced in trying to get an education. She holds a book with a quote from her writings: “The most unforgivable crime is to place people’s stature in doubt.”

_________

This post is part of the GLBT Saints series at the Jesus in Love Blog. Saints and holy people of special interest to gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people and our allies are covered on appropriate dates throughout the year.

Icons of Sor Juana de la Cruz and many others are available on cards, plaques, T-shirts, mugs, candles, mugs, and more at Trinity Stores

Icons of Sor Juana de la Cruz and many others are available on cards, plaques, T-shirts, mugs, candles, mugs, and more at Trinity Stores

Published on April 17, 2013 08:22

April 13, 2013

LGBT litany of the saints: Harvey Milk, pray for us; Joan of Arc, pray for us...

A Dignity Litany of the Saints

By Dr. Rachel Waltz, 2013

Lord have Mercy

Christ have Mercy

Lord have Mercy

Mary, Mother of God; Pray for us

Harvey Milk

; Pray for us

Harvey Milk

; Pray for us

St. Joan of Arc ; Pray for us

Our brothers and sisters who died at the hands of strangers; Pray for us

Matthew Shepard ; Pray for us

Our sisters and brothers who died in concentration camps; Pray for us

St. Anselm, who called another man “Beloved”; Pray for us

All those who died not knowing their worth; Pray for us

St. George, the androgynous warrior; Pray for us

Our sisters and brothers who died at the hands of loved ones; Pray for us

Mary, Mother of us all; Pray for us

Saints Perpetua and Felicity

, who bestowed the kiss of peace on each other before being martyred; Pray for us

Saints Perpetua and Felicity

, who bestowed the kiss of peace on each other before being martyred; Pray for us

All Ye Holy Men and Women; Pray for us

Those taken from us by AIDS; Pray for us

St. John the Evangelist

, who loved Christ fiercely; Pray for us

St. John the Evangelist

, who loved Christ fiercely; Pray for us

All Ye Holy Women and Men; Pray for us

____________________________________________________________________

Notes from Kittredge Cherry:

This prayer stunned me with its direct approach: Let’s just ask the queer saints to pray for us!

I have been blogging about LGBT saints since 2009, but I never thought of putting them into a traditional prayer format like this.

I was so moved by this prayer that I asked Dr. Rachel Waltz to let me share it on the Jesus in Love Blog. She wrote the prayer for Dignity , an organization supporting LGBT rights in the Roman Catholic Church. Thank you, Rachel, for permission to post your prayer here!

The standard Litany of the Saints is a formal prayer used in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Orthodox and Lutheran traditions. The usual version does address a few queer saints, including the same Perpetua and Felicity who are named in the Dignity version.

Visit the LGBT Saints page at jesusinlove.org/saints.php for more info on saints of special interest to queer people and our allies. It provides easy access to my profiles of 55 LGBT saints: 31 traditional Christian saints and 24 alternative figures. Along with the official saints, there are martyrs, prophets, mystics, witnesses, holy people, deities and religious figures of special interest to LGBTQ people and our allies.

___

Image credits:

Most of the icons shown can be purchased as cards, plaques, T-shirts, mugs, candles, and framed prints from TrinityStores.com.

"Harvey Milk of San Francisco" by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

"St. Joan of Arc" by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

"Saints Perpetua and Felicity" by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

“The Passion of Matthew Shepard” by William Hart McNichols © www.fatherbill.org

"Christ the Bridegroom" (John the Evangelist with Jesus) by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

___

Related links:

Why we need LGBT saints (A queer theology of sainthood by Kittredge Cherry)

Rainbow Christ prayer (by Kittredge Cherry and Patrick Cheng)

By Dr. Rachel Waltz, 2013

Lord have Mercy

Christ have Mercy

Lord have Mercy

Mary, Mother of God; Pray for us

Harvey Milk

; Pray for us

Harvey Milk

; Pray for us

St. Joan of Arc ; Pray for us

Our brothers and sisters who died at the hands of strangers; Pray for us

Matthew Shepard ; Pray for us

Our sisters and brothers who died in concentration camps; Pray for us

St. Anselm, who called another man “Beloved”; Pray for us

All those who died not knowing their worth; Pray for us

St. George, the androgynous warrior; Pray for us

Our sisters and brothers who died at the hands of loved ones; Pray for us

Mary, Mother of us all; Pray for us

Saints Perpetua and Felicity

, who bestowed the kiss of peace on each other before being martyred; Pray for us

Saints Perpetua and Felicity

, who bestowed the kiss of peace on each other before being martyred; Pray for usAll Ye Holy Men and Women; Pray for us

Those taken from us by AIDS; Pray for us

St. John the Evangelist

, who loved Christ fiercely; Pray for us

St. John the Evangelist

, who loved Christ fiercely; Pray for usAll Ye Holy Women and Men; Pray for us

____________________________________________________________________

Notes from Kittredge Cherry:

This prayer stunned me with its direct approach: Let’s just ask the queer saints to pray for us!

I have been blogging about LGBT saints since 2009, but I never thought of putting them into a traditional prayer format like this.

I was so moved by this prayer that I asked Dr. Rachel Waltz to let me share it on the Jesus in Love Blog. She wrote the prayer for Dignity , an organization supporting LGBT rights in the Roman Catholic Church. Thank you, Rachel, for permission to post your prayer here!

The standard Litany of the Saints is a formal prayer used in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Orthodox and Lutheran traditions. The usual version does address a few queer saints, including the same Perpetua and Felicity who are named in the Dignity version.

Visit the LGBT Saints page at jesusinlove.org/saints.php for more info on saints of special interest to queer people and our allies. It provides easy access to my profiles of 55 LGBT saints: 31 traditional Christian saints and 24 alternative figures. Along with the official saints, there are martyrs, prophets, mystics, witnesses, holy people, deities and religious figures of special interest to LGBTQ people and our allies.

___

Image credits:

Most of the icons shown can be purchased as cards, plaques, T-shirts, mugs, candles, and framed prints from TrinityStores.com.

"Harvey Milk of San Francisco" by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

"St. Joan of Arc" by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

"Saints Perpetua and Felicity" by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

“The Passion of Matthew Shepard” by William Hart McNichols © www.fatherbill.org

"Christ the Bridegroom" (John the Evangelist with Jesus) by Brother Robert Lentz, OFM, TrinityStores.com

___

Related links:

Why we need LGBT saints (A queer theology of sainthood by Kittredge Cherry)

Rainbow Christ prayer (by Kittredge Cherry and Patrick Cheng)

Published on April 13, 2013 11:58

April 6, 2013

Jesus Appears at Emmaus (Gay Passion of Christ series)

20. Jesus Appears at Emmaus (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

Collection of Jodi and Michael Simmons

“When he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them. And their eyes were opened and they recognized him.” -- Luke 24:30-31 (RSV)

Three travelers share a meal together in “Jesus Appears at Emmaus” from “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a series of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard. Three travelers share a meal together in “Jesus Appears at Emmaus.” Jesus is hard to recognize with his hair hidden under a bright blue ski cap. He sits at a restaurant table, breaking a loaf of bread. His companions, a man and a woman, touch in an attitude of prayer. The setting looks like a contemporary airport lounge with large windows. The table is nicely set with a red rose and generic salt and pepper shakers. Suitcases in the foreground confirm that they are traveling. It is a normal scene of friends eating together, until the viewer recognizes Jesus. And that is the point.

The painting illustrates the Biblical story of two disciples who met the risen Christ on the road, but didn’t recognize him at first. A disciple named Cleopas and his unnamed companion encountered the stranger on the way to Emmaus, a village seven miles from Jerusalem. They confided in him about their sadness over Jesus’ crucifixion and the disappearance of his corpse. The mysterious stranger listened and comforted them by using scripture to explain what happened. Impressed, the disciples persuaded him to join them for supper in Emmaus. When the stranger blessed and broke the bread, they connected completely. Suddenly they recognized Jesus.

The Emmaus story fits the mythic pattern of the magical traveling companion who appears unexpectedly and offers help. Such legends were common in medieval Europe when the practice of pilgrimage was important and widespread. Artists have been depicting Emmaus since the fifth century, but in the Middle Ages they gave more attention to the scene of encounter on the road. Jesus wore a large pilgrim’s hat to explain why his disciples failed to identify him. Pilgrimage fell out of favor in the 16th century with the Reformation. The supper scene, with all its Eucharistic implications, became increasingly prevalent. Artists began to focus on the dramatic moment of recognition, with famous versions painted by Rembrandt in the Netherlands and Caravaggio in Italy. In modern times the supper at Emmaus lost much of its appeal to artists. The mood and style of Blanchard’s Emmaus are reminiscent of 20th-century American painter Edward Hopper. Like Hopper, Blanchard finds the poetry in an anonymous urban environment, capturing the elusive interaction of people in a quiet moment just before something happens.

Artists of the past generally assumed that both disciples at Emmaus were male, but Blanchard brings the episode into the present and makes one disciple female, subtly communicating that gender does not limit a person’s relationship with God. The woman wears a headscarf, perhaps a hijab. Jesus may be sharing a meal with Muslim refugees. That possibility is especially powerful because Blanchard painted his Passion series in the aftermath of 9/11 attacks by Islamic terrorists. He strategically places the red rose so it blooms over Jesus’ heart, echoing the Sacred Heart motif in which Jesus exposes his physical heart as a symbol of his love and sacrifice.

Blanchard’s Emmaus painting now hangs in the kitchen of Jodi and Michael Simmons. They owned JHS Gallery in Taos, New Mexico, when Blanchard’s gay Passion series was displayed there in a 2007 group show. “We purchased the painting because we felt it most accurately captured the spirit of what we intended by the entire exhibition ‘Who Do You Say That I Am? Visions of Christ, Gender, and Justice,’” Jodi explained. “The Supper at Emmaus has always been one of both Michael and my favorite Gospel stories. I think it is the best example of ‘mature’ Christianity. Life is a journey; we meet many travelers and experiences along the way. To be able to be clear and awake enough to recognize the Light and Presence of God in all places, with all people, is a great, great milestone. Michael and I both think that it is absolutely the best image of this difficult to convey spiritual reality that we have ever seen.”

The Emmaus story has parallels with the queer spiritual journey. The disciples discovered Jesus after they left their faith community in Jerusalem. Most of the others were hiding there in fear, refusing to believe in the resurrection. The disciples on the road from Jerusalem to Emmaus are like LGBT people who turn their backs on their churches of origin -- and then find God on the outside! In the Bible narrative Jesus disappears as soon as he is recognized. The disciples return immediately to Jerusalem to tell the other disciples what happened. Likewise, some LGBT Christians feel called to return to religious institutions to proclaim their fresh understanding of the all-inclusive Christ.

“For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” -- Matthew 18:20 (RSV)

Two travelers met a stranger on the way to a village called Emmaus. While on the road they told the stranger about Jesus: the hopes he stirred in them, his horrific execution, and Mary’s unbelievable story that he was still alive. Their hearts burned as the stranger reframed it for them, putting it in a larger context. They convinced him to stay and join them for dinner in Emmaus. As the meal began, he blessed the bread and gave it to them. It was one of those moments when the presence of God breaks through ordinary life. Suddenly they saw: The stranger was Jesus! He had been with them all along. Sometimes even devout Christians are unable to see God’s image in people who are strangers to them, such as LGBT people or others who have less social status. People can also be blind to their own sacred worth. But at any moment, the grace of an unexpected encounter can open our eyes.

Come and travel with me, Jesus. Or are you already here?

___

This is part of a series based on “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a set of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard, with text by Kittredge Cherry. For the whole series, click here.

Scripture quotations are from Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, and 1971 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Published on April 06, 2013 10:52

March 31, 2013

Queer Christ Rising: Happy Easter from Jesus In Love and Kittredge Cherry!

"Queer Christ Rising" by Andrew Craig Williams

"Queer Christ Rising" by Andrew Craig WilliamsHappy Easter! Christ is risen! Rejoice!

Jesus wears a glowing rainbow as he steps up from his tomb in "Queer Christ Rising" by Andrew Craig Williams (with a little help from Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld). The title in Welsh is “Crist Queer yn Codi.” Williams is a queer artist, writer and music maker based in Wales who blogs at andrewcraigwilliams.blogspot.com. He created the Easter images this year and last year specifically for Jesus in Love's Easter greeting. It's becoming quite a tradition!

For the true meaning of Easter, check out The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision with art by Douglas Blanchard and expanded commentary by Kittredge Cherry.

You are invited to give to my Easter offering to support my work at Jesus in Love for LGBT spirituality and the arts. Give now by clicking by visiting my donate page .

Thank you to everyone for the many ways you show support. Happy Easter!

Published on March 31, 2013 07:24

Day 8: Jesus rises, appears to Mary and friends, and more (Gay Passion of Christ series)

18. Jesus Rises (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

18. Jesus Rises (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard“I am the resurrection and the life.” -- John 11:25 (RSV)

A handsome young Christ in blue jeans leads a joyous jailbreak in “Jesus Rises” from “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a series of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard. He holds hands with a prisoner as he steps upward, leading the captives to freedom. Jesus still bears the wounds of his crucifixion, but he glows with life and health. For the first time in this series, Jesus also has a halo. Beams of light shoot from his head in four directions, forming a diagonal cross behind him. Jesus does not bask in his own glory, but is determined to use his new-found power to free others. Christ is even more powerful as a liberator because he is also one of the prisoners. His inner light illuminates the shadowy crowd behind him.

Blanchard dares to paint a communal resurrection. One prisoner raises a fist in victory, a broken chain dangling from his shackled wrist. Another waves his hat in celebration. The scene can be read as “gay” because Jesus appears to hold hands with another man. The arch motif recurs in the brick wall behind them, but this time Jesus rises above it. Even the picture frame cannot hold back the risen Christ. He heads directly for the viewer, making eye contact, ready to burst through the flat surface of the image and into our lives. The frame cracks open at the top as light breaks through in this naturalistic yet supernatural scene. The words painted on the inseparable faux frame inform the viewer that this is the moment of cosmic significance when “Jesus Rises.” He overcomes death itself in an updated vision of the first Easter.

The resurrection is one of the most difficult parts of the Passion story for modern people, who mistrust miracles and are suspicious of happy endings. Artists and theologians struggle to reconcile a realistic understanding of the human condition with hope for a tortured world. Skeptics question whether the resurrection really happened, but it is central to the faith of most Christians. Easter is when Jesus becomes more than a great teacher, when minds are challenged to stretch and take a leap of faith. By rising from the dead Jesus completes the mystery of saving a broken world and embodies a new truth: Love transcends history; love is stronger than death. Death ceases to be a prison and becomes a passage to new life.

Jesus was a unique historical person, but he also epitomizes the sacred archetype of the god-man hero who returns from the dead with new powers to help others. There are many ancient myths of gods who die and return, sometimes in harmony with the seasons. Cycles of death and rebirth repeat in nature and in the hearts of people who must let parts of themselves “die” in order to grow. Christ lives again the actions of countless martyrs, prophets, and humanitarians throughout history up to the present. Jesus triumphs not by denying death, but by moving through it. Ultimately he unites birth and death in himself.

Illustrating the resurrection has always been a challenge for artists. The Bible doesn’t describe the actual moment when Jesus rose from the dead, but instead conveys the good news with reports of the empty tomb and appearances of the risen Christ. For more than a thousand years artists followed suit and avoided depicting the resurrection itself. Even the traditional Stations of the Cross stops short of the resurrection. The subject became more common in art starting in the twelfth century. At first Christ was usually shown stepping out of a Roman-style sarcophagus. Then artists began to picture Jesus hovering in the air. The 16th-century Isenheim Alterpiece by Matthias Grünewald matches its horrific crucifixion with an equally extreme resurrection in which a radiantly robust Jesus floats above his tomb, serenely awake. But church authorities clamped down on the trend, insisting that Jesus’ feet remain firmly on the ground. Renaissance artist Leonardo Da Vinci pioneered a more natural approach with Jesus emerging from a rock-hewn cave.

In art history it is almost unprecedented to see others rising along with Jesus. Usually Jesus rises alone, perhaps accompanied by angels and bowling over or even trampling upon the Roman guards outside the door to his tomb. Blanchard’s group scene has a lot in common with another artistic tradition. Artists show Jesus rescuing the souls of the dead in a scene known as the Anastasis or Harrowing of Hell, but that is usually a separate event before the resurrection. The subject arose in Byzantine culture and then spread to the West around the eighth century. It continues to be more prominent in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Blanchard cites English Romantic artist William Blake as a visual source for some of his resurrection and post-resurrection imagery.

The original painting “Jesus Rises” hangs in my own home, a gift from the artist. Blanchard wanted me to have this particular painting because it brought us together. In 2005 was hunting for queer Christian images for my JesusInLove.org website, which was still in the design stage. It was hard to find any kind of LGBT-oriented Christ figures, but the rarest of all was the queer resurrection. I was delighted when an Internet search finally led me to Blanchard’s “Jesus Rises.” After emails, letters, and phone calls, he eventually agreed to let me use it on my website. Later I shared more of his Passion series in my book “Art That Dares” and a 2007 exhibit that I helped organize at JHS Gallery in Taos. “Jesus Rises” hangs in my living room, where it serves as a constant reminder to maintain hope no matter what happens.

Blanchard’s resurrection does not occur in a vacuum or even in a lonely cave. His Jesus is no isolated individual experiencing a one-of-a-kind miracle, but first in the diverse group that will become the body of Christ in the world. He leads an uprising, as much insurrection as resurrection. These particular “prisoners” are the dead, but the prison can stand for any kind of limitation, including the closets of shame where LGBT people hide. The struggle to reconcile the resurrection with harsh reality can be especially tough for LGBT people who have endured hate crimes, discrimination, and the ravages of the AIDS epidemic. The risen Christ leads the way to a state of being where hate does not always lead to more hate, and anger becomes a motivation for life, not destruction.

For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. -- -- Romans 6:5 (RSV)

Christ lives! Nobody knows exactly how it happened, but Jesus rose to new life on the third day after his crucifixion. The mystery of resurrection replaced the law of cause and effect with a new reality: the law of love. Jesus lives in our hearts now. Just as he promised, he freed people from all forms of bondage. Captives are released from every prison. LGBT people are free to leave every closet of shame. Christ glows with the colors of all beings. People of all kinds -- queer and straight, old and young, male and female and everything in between, of every race and age and ability -- together we are the body of Christ.

Jesus, welcome back!

19. Jesus Appears to Mary (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

19. Jesus Appears to Mary (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard“Now when he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene.” -- Mark 16:9 (RSV)

Two friends meet at sunrise in “Jesus Appears to Mary.” They circle each other as Mary Magdalene gestures with happy surprise at finding Jesus alive in the graveyard. It almost looks like Jesus is dancing with his own shadow. A patch of sunlight catches the risen Christ, now restored to health and handsome in his blue jeans. Mary, a black woman, remains in darkness with her back to the viewer. The morning star shines in a gorgeous blue sky while the first rays of dawn awaken the spring-green grass. The frame itself is green -- even the faux wood has sprung to life!

On the distant horizon are excavating machines. A body of water separates Jesus and Mary from the faraway city skyline. They are surrounded by numbered gravestones. The one behind Jesus is marked “124” -- the same number on the mysterious tag around Jesus’ neck in the first painting of this series. The artist has stated that he chose “124” because it has no special meaning in Christianity. His Jesus died with a random number, a human castoff stripped of his name. The gravestones and setting look like Hart Island, a public cemetery for the unknown and indigent in New York City. Operated by prison labor, Hart Island is the world’s largest tax-funded cemetery with daily mass burials and almost a million people buried there.

First Mary was blinded by grief, and then she saw a deeper truth: The living Christ is here now. In such moments, supreme awareness breaks through ordinary perception, awakening awe for the ultimate mystery that transcends all names. The scene can symbolize any “aha moment” when sudden clarity leads to life-changing insight.

The dynamic tension between the figures suggests that this is the moment known as “Noli me tangere,” the Latin phrase usually translated as “Don’t touch me.” Jesus spoke these words to Mary Magdalene in John 20:17 when they meet after his resurrection. In John’s gospel, Mary went to visit Jesus’ tomb before sunrise on Easter. She was distraught that his corpse was missing -- until the risen Christ called her name. Overcome with emotion, she started to hug him, but he stopped her with a request that has multiple translations. The original Greek is best translated as “Stop clinging to me.” But the Latin translation is embedded in cultural tradition: “Don’t touch me (noli me tangere) for I have not yet ascended.” The scene has been an iconographic standard for artists throughout the Christian world since late antiquity. Modern artists are still keen to portray the suffering and death of Jesus, but most won’t touch the subject of his resurrection appearances. Indirect references continue. For example Picasso’s mysterious 1903 allegorical painting “La Vie,” the masterpiece of his Blue Period, includes references to “Noli Me Tangere” by Renaissance painter Antonio da Correggio.

Jesus appearing to Mary is good news for all the disenfranchised, including today’s LGBT people. Like Jesus here, LGBT people cannot take touch for granted and become untouchable. The reason that Jesus rejects Mary’s touch is because he has “not yet ascended,” but in a gay vision it also suggests an aversion for heterosexual contact. Jesus made his first post-resurrection appearance to a woman in an era when women weren’t even allowed to testify at legal proceedings. And yet the risen Christ chose a woman as his first witness. Mary Magdalene has an undeserved reputation for sexual sins. The church mistakenly labeled her as a prostitute for centuries, but the Bible does not support this view. Progressive theologians are reclaiming her as a role model for church leaders. The Bible portrays Mary Magdalene as the most important woman follower of Jesus. She supported his ministry with her resources, traveled with him on his teaching tours, witnessed his crucifixion, and hurried to his tomb before sunrise. In Luke’s gospel angels ask a question to Mary Magdalene and the other women at the empty tomb: “Why do you seek the living among the dead?” LGBT Christians and allies sometimes ask themselves the same question as they seek the living Christ in the rusty, deadening rituals and relics of the institutional church.

“Why do you seek the living among the dead?” -- Luke 24:5 (RSV)

Mary Magdalene went to the tomb of her friend Jesus early on Sunday morning. It was empty! She started crying and someone came up to her. Mary thought he was the gardener until he spoke her name. Her heart leaped as she recognized Jesus. Human beings often miss the presence of God right before our eyes. Like Mary, we get lost in our emotions. It feels like God is far away or even dead. Then something happens and suddenly we see: God was with us all along. Jesus chose an unlikely person as the first witness to his resurrection. Women were second-class citizen in the time of Jesus, not unlike LGBT people in some countries today. But Jesus, who loved outcasts, gladly revealed himself to the woman who came looking for him. Christ is ready to speak to each of us by name, even if we are looking in all the wrong places.

Jesus, where are you now? Will you speak to me?

The final five paintings in the gay Passion series are presented below with short meditations only. They will be re-posted with full commentary on appropriate dates between now and Trinity Sunday (May 26).

20. Jesus Appears at Emmaus (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

20. Jesus Appears at Emmaus (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard“When he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them. And their eyes were opened and they recognized him.” -- Luke 24:30-31 (RSV)

“For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” -- Matthew 18:20 (RSV)

Two travelers met a stranger on the way to a village called Emmaus. While on the road they told the stranger about Jesus: the hopes he stirred in them, his horrific execution, and Mary’s unbelievable story that he was still alive. Their hearts burned as the stranger reframed it for them, putting it in a larger context. They convinced him to stay and join them for dinner in Emmaus. As the meal began, he blessed the bread and gave it to them. It was one of those moments when the presence of God breaks through ordinary life. Suddenly they saw: The stranger was Jesus! He had been with them all along. Sometimes even devout Christians are unable to see God’s image in people who are strangers to them, such as LGBT people or others who have less social status. People can also be blind to their own sacred worth. But at any moment, the grace of an unexpected encounter can open our eyes.

Come and travel with me, Jesus. Or are you already here?

21. Jesus Appears to His Friends (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

21. Jesus Appears to His Friends (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard“See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself; handle me, and see.” -- Luke 24:39 (RSV)

“The doors were shut, but Jesus came and stood among them, and said, ‘Peace be with you.’” -- John 20:26 (RSV)

Jesus’ friends were hiding together, afraid of the authorities who killed their beloved teacher. The doors were shut, but somehow Jesus got inside and stood among them. They couldn’t believe it! He urged them to touch him, and even invited them to inspect the wounds from his crucifixion. As they felt his warm skin, their doubts and fears turned into joy. Jesus liked touch. He often touched people in order to heal them, and he let people touch him. He defied taboos and allowed himself to be touched by women and people with diseases. He understood human sexuality, befriending prostitutes and other sexual outcasts. LGBT sometimes hide themselves in closets of shame, but Jesus wasn’t like that. He was pleased with own human body, even after it was wounded.

Jesus, can I really touch you?

22. Jesus Returns to God (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

22. Jesus Returns to God (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard“As they were looking on, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight.” -- Acts 1:9 (RSV)

“As the bridegroom rejoices over the bride, so shall your God rejoice over you.” -- Isaiah 62:5 (RSV)

Words and pictures cannot express all the bliss that Jesus felt when he returned to God. Some compare the joy of a soul’s union with the divine to sexual ecstasy in marriage. Perhaps for Jesus, it was a same-sex marriage. Jesus drank in the nectar of God’s breath and surrendered to the divine embrace. They mixed male and female in ineffable ways. Jesus became both Lover and Beloved as everything in him found in God its complement, its reflection, its twin. When they kissed, Jesus let holy love flow through him to bless all beings throughout timeless time. Love and faith touched; justice and peace kissed. The boundaries between Jesus and God disappeared and they became whole: one Heart, one Breath, One. We are all part of Christ’s body in a wedding that welcomes everyone.

Jesus, congratulations on your wedding day! Thank you for inviting me!

___

Bible background

Song of Songs: “O that you would kiss me with the kisses of your mouth!”

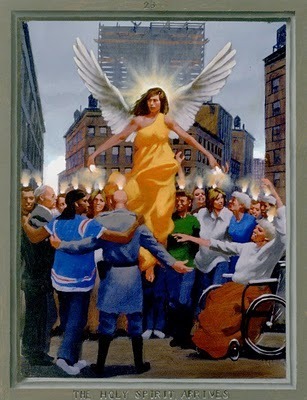

23. The Holy Spirit Arrives (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

23. The Holy Spirit Arrives (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard“There appeared to them tongues as of fire, distributed and resting on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit.” -- Acts 2:3-4 (RSV)

“I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and the young shall see visions, and the old shall dream dreams.” -- Acts 2:17 (Inclusive Language Lectionary)

Jesus promised his friends that the Holy Spirit would come to empower them. They were together in the city on Pentecost when suddenly they heard a strong windstorm blowing in the sky. Tongues of fire appeared and separated to land on each one of them. Jesus’ friends were flaming, on fire with the Holy Spirit! Soon the Spirit led them to speak in other languages. All the excitement drew a big crowd. Good people from every race and nation came from all over the city. They brought their beautiful selves like the colors of the rainbow. Each one was able to hear about God in his or her own language. The story of Jesus has been translated into many languages. Now the Gospel is also available with an LGBT accent. Inspired by the Holy Spirit, we too can hear God’s story. We are the flaming friends of Jesus!

Come, Holy Spirit, and kindle a flame of love in my heart.

24. The Trinity (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

24. The Trinity (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard“Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”-- Luke 23:43 (RSV)

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the realm of heaven.” -- -- Matthew 5:10 (Inclusive Language Lectionary)

God promises to lead people out of injustice and into a good land flowing with milk and honey. We can travel the same journey that Christ traveled. His spirit and legacy live on in everyone who remembers his Passion. Opening to the joy and pain of the world, we can experience all of creation as our body -- the body of Christ. As queer as it sounds, we can create our own land of milk and honey. The Holy Spirit inspires each person to see heaven in his or her own way. Look, the Holy Spirit celebrates two men who love each other! She looks like an angel as She protects the same-sex couple. Are the men Jesus and God? No names can fully express the omnigendered Trinity of Love, Lover, and Beloved… or Mind, Body, and Spirit. God is madly in love with everybody. As Jesus often said, heaven is here among us and within us. Now that we have seen a gay vision of Christ’s Passion, we are free to move forward with love.

Jesus, thank you for giving me a new vision!

___

Click the titles below to view previous installments in the series:

1. Son of Man (Human One) with Job and Isaiah

2. Jesus Enters the City

3. Jesus Drives Out the Money Changers

4. Jesus Preaches in the Temple

5. The Last Supper

6. Jesus Prays Alone

7. Jesus Is Arrested

8. Jesus Before the Priests

9. Jesus Before the Magistrate

10. Jesus Before the People

11. Jesus Before the Soldiers

12. Jesus Is Beaten

13. Jesus Goes to His Execution

14. Jesus Is Nailed to the Cross

15. Jesus Dies

16. Jesus Is Buried

17. Jesus Among the Dead

18. Jesus Rises

This concludes the series based on “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a set of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard, with text by Kittredge Cherry. For the whole series, click here.

If you enjoyed the Gay Passion of Christ series, please give now to the Jesus in Love Easter offering. Your gifts keep this blog going.

Scripture quotations are from Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, and 1971 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations are from the Inclusive Language Lectionary

, copyright © 1985-88 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

, copyright © 1985-88 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.____

This post is part of the Queer Christ series by Kittredge Cherry at the Jesus in Love Blog. The series gathers together visions of the queer Christ as presented by artists, writers, theologians and others. More queer Christ images are compiled in my book Art That Dares: Gay Jesus, Woman Christ, and More

.

.

Published on March 31, 2013 07:10

Give now: Easter offering for Jesus In Love

Kittredge Cherry holding “Jesus Rises” by Douglas Blanchard (photo by Audrey)

Kittredge Cherry holding “Jesus Rises” by Douglas Blanchard (photo by Audrey) I am collecting an Easter offering to support my work at Jesus in Love for LGBT spirituality and the arts.

Give now by clicking the “GoFundMe” button below or visiting my donate page .

Thank you! Your gifts help me provide resources such as the Gay Passion of Christ series and the LGBT Stations of the Cross, plus much more throughout the year.The Jesus in Love Blog gets 187,000 pageviews per year and my e-newsletter has more than 800 subscribers.Numbers alone can’t express the impact of Jesus in Love on people’s lives. Listen to the voices of readers:

“It’s very, very important to reach LGBTQ's with the love of God, and I don’t know anyone who does that better than you.” -- Josh Thomas

“Your boldness for the Queer Christ inspires me and gives me joy.” -- Brian HutchisonRight-wing rants also show that my work at Jesus in Love is effective:

Blasphemy 101: ‘Lesbian Christian’ Kittredge Cherry Offers ‘Rainbow Christ Prayer’ was posted by Americans for Truth about Homosexuality. Headed by Peter LaBarbera, it is classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.By supporting Jesus in Love, you stand up for freedom of speech and freedom of religion. You empower people to experience the divine in new ways.Jesus in Love is my gift to the world. What do you feel called to give in return? Click here to give now. I am passionately committed to Jesus in Love because it grew out of my own personal journey as a lesbian Christian. Since I launched JesusInLove.org in 2005, it has grown to include a popular blog and e-newsletter. You can read my bio at this link. Many thanks to EVERYONE who has given their time, talent and resources. Have a joyous Easter!

Published on March 31, 2013 07:06

March 30, 2013

Day 7: Jesus is Buried; Jesus Among the Dead (Gay Passion of Christ series)

16. Jesus is Buried (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

“They took the body of Jesus, and bound it in linen cloths with the spices, as is the burial custom.” -- John 19:40 (RSV)

A mother mourns her dead son in “Jesus is Buried” from “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a series of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard. Mary leans over the body of Jesus, ready to kiss his ashen face goodbye. Crucifixion wounds are still visible on his wrists, feet, and side. An identification tag from a morgue is tied around his wrist. His corpse is bloodless and wrapped in a plain white shroud. The gravedigger shovels dirt from the grave where Jesus will be buried. A simple wooden coffin waits. The night is dark with city lights in the distance.

The simple dignity of the scene conveys the deepest sorrow and the finality of death. The burial of Jesus is described in all four gospels and discussed in the earliest summaries of the Christian message in the epistles. His burial has been important to Christians since Biblical times because it confirms that Jesus really died, thus laying the groundwork for the miracle of his resurrection. The Bible reports that Jesus was laid in a rock-hewn tomb with the help of his disciple Joseph of Arimathea, while Mary Magdalene and “the other Mary” watched.

The subject is common in art history, where it is known as the Lamentation. A notable version was painted by Italian Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna, who showed Jesus’ foreshortened cadaver on a slab, wounded feet first. Like most scenes from the Passion, the Lamentation was not depicted at all until the 11th century, and then proliferated in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The last two scenes in the traditional Stations of the Cross show Jesus being taken down from the cross and buried in his tomb. Nothing touched viewers more deeply than a mother’s grief, so artists gave an increasingly central role to Mary. They focused on the heart-rending moment when the bereaved mother cradles her son’s dead body in a specific type of Lamentation known as a Pieta (Italian for “pity”). The most famous Pieta is the sculpture by Michelangelo at St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City. It has become one of the Passion’s most iconic scenes, often copied or parodied to make a point.

Modern artists have used his Pieta composition to express other forms of grief. Some relocate it or switch the characters to make a political statement. Others, such as German Surrealist Max Ernst, use it to depict the unconscious mind. He replaced Jesus and Mary with a self-portrait of the artist held by his stern, staunchly Catholic father in “Pieta or Revolution by Night.”

Some versions address the impact of AIDS and homophobia on LGBT people. The magnitude of the AIDS death toll was made worse by Christians who saw the disease as God’s punishment for homosexuality. In her famous Ecce Homo series, Swedish artist Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin photographed an emaciated gay AIDS patient cradled by a leather bar employee in the AIDS ward of a Stockholm hospital. American painter Matthew Wettlaufer’s “Pieta” shows a gay man at the bedside of his dying lover while bombs drop and a blanket lists the names of war-torn countries and gay-bashing victims. “Stations of the Cross: The Struggle for LGBT Equality” by Mary Button weaves together past and present to make deadly comparisons: Jesus is taken down from his cross beside a map of states banning same-sex marriage, and LGBT youths driven to suicide watch as he is laid in his tomb.

Blanchard’s understated Lamentation is closely related to the next two paintings in his gay vision of the Passion. All three images use dark tones to convey Jesus’ experiences with death and the underworld. Life, not death, was Jesus’ focus, and he gave mixed messages about mourning the dead. He promised comfort for those who mourn. He was so concerned about the welfare of his mother and his beloved disciple after his death that from the cross he declared them to be family for each other. But he did not have an overly sentimental attachment to family or funeral customs. He even ordered a disciple to skip his father’ funeral, saying, “Leave the dead to bury their own dead.”

“You are dust, and to dust you shall return.” -- Genesis 3:19 (RSV)

After Jesus died, the authorities allowed one of his friends to take his body for burial. Almost all of his many supporters were gone. Jesus’ body was laid to rest in a fresh tomb at sundown, just before the sabbath began. When they buried him, they also buried a beautiful part of themselves. Sometimes the humiliations continue even after death… when homophobes picket the funerals of the LGBT people and other outcasts, when mortuaries refuse to handle the bodies of AIDS patients, when families exclude same-sex partners from memorial services, on and on. Jesus understood grief and didn’t try to suppress it. He said, blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Jesus, I wait in silence at your grave.

17. Jesus Among the Dead (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

Collection of Robert Wilder Nightingale

“Even the darkness is not dark to you.” -- Psalm 139:12 (Inclusive Language Lectionary)

Endless rows of corpses fill a vast black space in “Jesus Among the Dead.” Even in death, Jesus is not separate from humanity. He lays with the stink, the dead bodies, and the skeletons -- a common man in a common grave. Jesus can be identified by his crucifixion wounds. His corpse only stands out because it has not begun to decompose. He glows just slightly with a sick luminescence. Jesus just lies there, not judging, not fixing, not rescuing. He is simply present with people in the darkest state of being. This must be hell, or some human holocaust. Perhaps there is no difference.

At first glance Blanchard’s painting looks almost entirely black. The painting challenges viewers to keep looking until their eyes adjust to the lack of light. Then shapes and meanings emerge from the shadows to offer uncomfortable wisdom from the depths. Mystical traditions say there power to be gained by descent into the dark netherworld of dreams, intuition, death, and the unknown. In the mass grave Jesus is fulfilling Isaiah’s prophecy that God’s suffering servant would be buried with “transgressors” and “the wicked.” The black void conveys utter despair over the meaninglessness of life.

The Bible doesn’t tell what Jesus experienced in the interlude between crucifixion and resurrection, but artists and theologians of the past were quick to fill the void. The Apostle’s Creed clearly states, “He descended into hell,” or in another translation, “He descended to the dead.” Artists traditionally show Jesus leading an uprising in hell. The subject is traditionally known as the Harrowing of Hell, when Christ descends to hell or limbo to rescue the souls held captive there since the beginning of time. Some churches mark the event on Holy Saturday by stripping their altars bare or covering them with black cloth.

Blanchard takes the dead Jesus to a whole new level. His Jesus is not triumphantly waking the deceased, at least not yet. He stays dead in the afterlife, sharing the reality of human powerlessness. A few artists, notably German Renaissance painter Hans Holbein, depicted the corpse of Jesus with gruesome realism. But Blanchard’s monolithically black visual vocabulary in “Jesus Among the Dead” has more in common with modern art, photography, and philosophy. He based the composition on documentary photographs of the Holocaust, especially photos of bodies laid out in long rows after the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp at Nordhausen in 1945. New Mexico gallery owner Robert Wilder Nightingale singled out “Jesus Among the Dead” to purchase for his private collection when it was exhibited in Taos in 2007. “To me the work is haunting. A nightmare I wish never to see happen in reality,” he explained.

This is one of the most difficult paintings in Blanchard’s Passion series because it’s hard to see anything at all in the gloom. It resembles the all-black abstract paintings done by American artist Ad Reinhardt in the 1960s. Reinhardt claimed that these were the “last paintings that anyone can paint” -- a fitting concept for Jesus among the dead. Reinhardt painted them in the era when the “God is dead” theological movement announced that there was no longer any cultural relevance for the idea of transcendent God acting in human history. Another precedent for Blanchard’s black image is the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington DC. Inscribed with a seemingly endless list of war casualties, the memorial stretches like a long, black gash in the earth.

The most significant memorial for many in the LGBT community is the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. More than 48,000 handmade panels commemorate those who died of AIDS, including thousands of gay men. Before effective treatments were developed in the 1990s, AIDS was stigmatized as the “gay plague” and the LGBT community felt like a war zone as thousands died. Fundamentalists preached that AIDS was God’s punishment for homosexuality and President Reagan kept silent. Lovers, friends, and family learned to show they cared by staying present with the dying. Meanwhile they advocated change through groups such as ACT UP, whose motto was “Silence = Death.”

The AIDS pandemic is part of a larger queer holocaust. Many LGBT people experience a kind of living death, trapped in the private hell of the closet. Some have wished themselves dead and even taken their own lives. Those who wore the pink triangle were exterminated in Nazi death camps. The tragic history of church-approved persecution for homosexuality stretches back to the 13th century, when the first “sodomites” were burned at the stake. In Blanchard’s vision, Jesus rests with them in the ashes.

There are many hells and many types of limbo in which people are trapped neither fully alive nor dead. For example, the US Supreme Court overturned state sodomy laws in 2003, but same-sex marriage is still illegal in almost every state, leaving most LGBT people to exist in a non-quite-legal limbo.

“He poured out his soul to death, and was numbered with the transgressors.” -- Isaiah 53:12 (RSV)

Like all human beings, Jesus eventually had to experience death. In effect, it was like he was buried in a mass grave with all humankind -- saints and sinners, queer and straight, male and female, all of us without exception, even the worst of us. His body rested in peace with the other corpses. Jesus lay buried like a seed waiting in the wintry earth. He didn’t believe death was the end. During his lifetime, he often talked about the afterlife. He said he would always be with us, connected like a vine to a branch. But when his body lay cold in the tomb, his friends and family simply missed him.

O God, can these bones live?

___

This is part of a series based on “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a set of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard, with text by Kittredge Cherry. For the whole series, click here.

Scripture quotation is from Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, and 1971 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Published on March 30, 2013 10:58

Q Spirit

Q Spirit promotes LGBTQ spirituality, with an emphasis on books, history, saints and the arts.

- Kittredge Cherry's profile

- 9 followers