Patricia C. Wrede's Blog, page 32

January 21, 2015

Why “There’s no Plot” Sometimes

Could you try an entry or two on punching up a sense of ‘there really is a plot here”? I’ve read several that I’ve thought were good but my husband grumbles had no plot. *I* thought there was one, but it’s not getting across to him. And he sees the same in our teen’s fiction.

I think your description nails the fundamental problem dead on: this reader is not getting “a sense that there really is a plot here.” The question then becomes, why does he have trouble seeing the plot, when you don’t? There are a couple of possibilities; some of them are susceptible to a writing solution, and some aren’t.

For starters, readers vary a lot in taste, preference, and reading conventions. For instance, some readers only recognize a plot if it is an action plot; they parse emotional or intellectual problems as subplots, if they recognize them as plots at all. At the other end of the scale are readers who like to work at the books they read, teasing out meaning and connections from obscure hints. For them, the typical action plot is too easy and too obvious (it is hard to miss or misinterpret explosions, fist-fights, battles, or chase scenes). Any book written with one end of this spectrum of readers in mind is unlikely to please the people at the other end, and there’s not much that can be done about it.

More commonly, though, when one reader sees a plot and another reader doesn’t, the reason is that seeing the plot depends on stuff that the writer has not actually put into the book. Sometimes, the missing thing is some background knowledge or other that the writer assumes is common knowledge but that isn’t (like a knowledge of Greek mythology or a familiarity with particular cultural norms). This is, obviously, extremely common with great books written by someone from a culture different from the reader – it’s why a lot of foreign-language books “lose a lot in translation,” and why stories from a hundred years ago or more frequently need lots of footnotes to explain things ranging from the significance of different styles of horse-drawn carriages to the meaning of a rude gesture that nobody has used in a couple of centuries.

The missing link isn’t always outside cultural or background knowledge, though. Sometimes it is more of an angle of attack, a point of view that is so clear and obvious to the writer that he/she doesn’t get it onto the page, except perhaps by implication. Readers who have a similar approach will instantly make the right assumptions about what is going on; everyone else has to dig for it or end up floundering.

And sometimes, the problem is the problem. That is, the thing that is supposed to be the central story problem is so obvious and important to the writer that it simply doesn’t occur to them that not everyone will instantly recognize it as of crucial importance to the main character. Saving The World is probably going to be important to any main character (though if the author forgets to mention that the reason the hero needs some odd item is to Save The World, it can be hard to understand why the main character is in such a hurry to locate a pair of scissors or a lost roller skate). A central problem that involves the main character deciding between taking a job at K-Mart and working at Taco Bell seldom seems as urgent or important, especially if the character him/herself has no reason to recognize this as a potentially life-changing decision.

When the story problem has a lot of emotional connection for the author, the author sometimes assumes that it will have an equal intensity for readers, and may even deliberately play it down a little to avoid being too obvious…or to avoid raking up the author’s own emotions around the subject. If the central problem is the sort of thing that most people recognize as emotionally intense, like abuse or dealing with the death of a friend or family member, damping the intensity a bit can work very well. If, however, the problem is something like losing a library card, which was highly traumatic for the author at age 8 but which most people aren’t likely to see as a big deal, downplaying how important this is to the main character is likely to result in an impression of non-plot, except among readers who already consider losing their library card to be a tragedy.

The other difficulty in this sort of situation – when the author is using something in the story that has a lot of personal emotional resonance for them – is that it can be a lot more difficult than usual for an author to judge what has gotten into the story. Years ago, I read a scene in which the author described an incident that anyone would recognize as emotionally intense – think watching a drunk driver in an SUV come straight at you, and then waking up in the hospital. The scene was brief, factual, and a bit clumsy…and what the author wanted was advice on how to “tone it down, because it is so intense.” It was intense for the author, because the scene was based on a real incident and just writing a minimalist version still gave that author the shakes…but for the reader, it was more of a “Yeah, that would have been bad, I guess” moment. It wasn’t involving or emotional, because the author’s emotions got in the way of putting the incident vividly on the page – it was already way too vivid in the author’s mind.

Notice that in all of the above cases, the “missing plot” problem has to do with something getting left out of the story. Usually, this is accidental, but occasionally an author has a deep and abiding horror of being too obvious (the way many authors have a horror of writing purple prose), and they’re leaning over too far backward. In any case, the solution to the “there is no plot here” feeling is to make the central story problem clearer, harder to achieve, or more obviously vital to the main character. If the author objects that the problem is already hard to achieve and/or vital to the main character’s health and happiness…well, if a significant percentage of one’s beta readers can’t find the plot, then the difficulty and/or importance of the central problem hasn’t gotten onto the page. (I can talk more about this in the next post, if people are interested.)

Also notice that there will always be differences in taste and preference. Back in high school, I had a friend whose taste in fiction ran very strongly toward things I considered over-the-top melodrama, verging on the hysterical. She considered my favorite books unemotional, cold, and full of almost robotic characters. With forty years of hindsight, I can see that it was a difference in taste, not necessarily in the quality of the prose, plotting, or characterization. There will always be readers who want every detail of the plot laid out clearly (whether it’s action-adventure, romance, or man-learns-lesson), and others who find it annoying to have stuff spelled out that they consider obvious. There will always be writers who have a horror of being obscure, and others who cannot stand the thought of being too obvious. Sometimes, all you can do is say, “I guess this isn’t your sort of story, then.”

January 18, 2015

What you are good at

Everybody is good at something. Nobody is good at everything.

At least 98% of the writers I know, faced with those two sentences, nod sort of absently at the first one and immediately start working out exactly how the second one applies to them – that is, they immediately start worrying about what they are bad at. Most of the people I know have a pretty good idea what their writing weaknesses are, even if none of us like talking about them much. The odd thing is that we spend so much time trying to find more things we’re bad at, supposedly in order to fix them.

In actuality, what’s most important are your writing strengths, how strong they are, and how well they fit what you are writing. Erasing mistakes and errors makes things less bad; it doesn’t necessarily improve their fundamentals. Getting rid of every single problem in a mediocre book will make it read more smoothly, but it won’t make it a great work of art. A writer who has lots of basic craft problems with plot can, with work, get rid of every last technical difficulty, but if the plot wasn’t interesting to start with, technical changes aren’t going to make it interesting. A writer whose strong point is creating intricate plots but who is weak on characterization will very likely have trouble selling to a genre in which characterization is fundamental (like literary fiction or Romance), but not have a problem selling a thriller.

So how does one identify one’s strengths? Hint: What things do you enjoy writing the most? Very few people enjoy doing something they are bad at. If you adore writing dialog or battle scenes or description, if the fun part is making up random stuff in the first few chapters, if you love seeing your plot come together or your characters unfold – those are probably things you do well.

Note that enjoying writing something doesn’t mean that the writing is fast or easy. Sometimes the stuff I enjoy writing most is labored over. Also note that I’m talking about stuff that you enjoy the writing. Some of the stuff I labor over, I enjoy because writing it is fun; other stuff, I enjoy because it is a challenge. When it is a challenge, it usually means that I am still learning how to be good at it. Of course, most people do not enjoy failing at something, either, so challenging stuff that I’m enjoying is usually stuff that I am “getting right.” (Final note on this: the fact that you are not enjoying something does not mean you are getting it wrong. This isn’t a reciprocal equation.)

Things that come fast and easy are sometimes just inspiration (which is unfortunately no guarantee that the result is any good). If, however, you always find dialog fast and easy to write, or you have to rein in your tendency to write pages of gorgeous description, that’s probably something you do well.

Next, what do you think you are good at? What do you think your writing strengths are? What do your friends and beta readers compliment you on – do they like the banter in general, or is there always a character they fall in love with, or do they say it was exciting and they couldn’t put it down?

Put all of these things together, and you should get an idea of what your writing strengths are. Bear in mind that sometimes, this is a matter of personal taste and preference. There are writers who have won multiple major awards whom I find virtually unreadable – I can get through one of their books, but it is an unpleasant slog. There are writers I admire or love whose work friends of mine bounce off in the same way. I do not believe that this means some of us have “bad taste” in style; I think it means that we have different tastes, full stop. So if you enjoy a particular aspect of writing, like what comes out, and find it easy and think you’re good at it, but you have people telling you that that aspect of your writing doesn’t work…it may be a matter of taste.

None of this is guaranteed to be right. This is not rocket science. Writing is not something that has been mathematically quantified, and an enormous amount of what constitutes “good writing” is a matter of taste, personal preference, and the conventions of particular groups and genres.

And it doesn’t matter whether your list of strengths is complete, or even mostly right, because what you do with your list of strengths is…you work on improving them. The payoff for going from mediocre plotting to pretty good plotting or pretty good characterization to very good characterization is generally a lot bigger than the payoff for going from terrible, horrible plotting (or dialog, or characterization, or whatever) to merely bad whatever-it-is.

How you work on improving involves two very obvious things: reading and writing.

You read stories by writers you think are doing whatever-it-is better than you do it, and observe what they are doing that you aren’t. Then you experiment with adding those things to your writing to see how they work. You also read stories by writers you think do whatever-it-is worse than you do it, and look for a) what you are doing that they aren’t (and decide whether doing more of it would help or be overkill), and b) things they are doing that you are also doing and that you maybe shouldn’t be (often, it is a lot easier to recognize an area that needs improvement if you spot it in somebody else’s work first).

The writing part is practice, practice, practice. I prefer to do my practicing on pay copy, i.e., on stories that I fully intend to sell. Depending on what aspect of writing I’m focusing on, I will sometimes construct a story so that it forces me to do whatever-it-is – five or six of my earliest novels were quite deliberate practice in various types of viewpoint and viewpoint structures. Some writers find that this makes them crazy – they don’t want to risk finding out halfway through a novel that they’ve totally messed up some extra-stretchy thing they’ve been trying, and the novel will have to be completely rewritten. So instead, these folks do exercises and “practice pieces” until they have enough of a comfort level to apply their new, growing skill to potential pay copy. Still others like the formality of a class, if they can find a good one.

When and how you practice is up to you and your process. The only thing that is not optional is, you have to do it. The writing fairy does not come down and leave beautiful new words on your computer without you actually doing anything. You have to write, yourself.

January 14, 2015

Deadlines

Deadlines. Some writers love them, some hate them, and some don’t seem able to finish anything unless they have one. And how many times have you heard someone say (not necessarily about writing) “I do my best work when I have a deadline to meet”?

Around a quarter of the writers I know have said something like this at one point or another (sometimes it’s not “I do my best work…” it’s “I get the most work done…” or even “I can only finish things…” but it’s the same principle). It’s a comforting story we tell ourselves, but I don’t think the folks who say this think about it much. Because what it sounds as if they are saying is “I can be creative on demand” or maybe even “I can only be creative if someone else demands I do so on their schedule.” (And doesn’t that put a spoke in their complaints about writer’s block, if all it takes to get them writing is someone else to say “I need that by Friday?”)

Nevertheless, it is perfectly obvious that a lot of writers do produce more when they have a deadline (even if they’ve missed it). I know several professionals who, when I think about it, haven’t managed to write anything but a proposal all the way through to the end since their first sale, unless they’ve sold it and have a deadline. What’s going on?

After doing some considerably thinking and observation, I’ve come to the conclusion that there are several rather different things in play. For different writers, one or another is primary, which is why you get such different reactions if you try to grill someone about their reaction to deadlines.

The writer doesn’t want to let someone else down.

Writing and other creative professions don’t fit very well into the kind of productivity paradigm that is epidemic in our society. If one is only writing for oneself, one’s writing tends to be seen as self-indulgence, something unessential that can be put off…or that can be polished continually until it is perfect (and it never is perfect). If someone else is waiting for it, though, that’s different. If that someone is going to be inconvenienced if the manuscript doesn’t get turned in – if the agent will have to spend extra time apologizing to editors, and the editor will have to rejigger the publication schedule and the art director will have a hole in his/her plans for keeping a particular artist busy…if a writer knows that’s going to happen, they are more likely to feel guilty if they miss the deadline. People don’t like feeling guilty, and generally don’t like letting people down, so they’re willing to work harder to avoid it.

Also, a writer who is writing “on spec” (on speculation, that is, without selling the work based on a proposal) has no assurance that the work in question will sell. When one is bogged down in the middle of a manuscript and one doesn’t want to have to think about it again, ever, a spec writer can decide that the thing is hopeless and will never sell, so there is no point in finishing. A writer who has sold the book can’t do that. The thing has sold; someone is waiting for it and has in most cases paid something already. The writer will force themselves to continue working through the times when progress is slow and they’re disheartened because they feel as if they have to. And it works.

The writer needs the money, or the career or ego boost, or something else that will only happen when the deadline is met.

A deadline doesn’t just mean an obligation on the writer’s part; it means that other things are going to happen, too. The obvious one is money: the next part of the advance usually arrives when the ms. is delivered, and if the writer has rent to pay or cats to feed, getting hold of that advance is important. Sometimes there are other things involved that are important to the writer (for instance, the editor has promised the top spot on the spring list if the writer can get the ms. in by a certain date, or there’s a big indie publishing festival coming up that will be a huge potential sales boost if the book can be finished by then).

Deadlines also frequently provide validation. The reason one has a deadline at all is usually because an editor wants the thing one is writing – and wants it badly enough to give one money for it. That kind of recognition is extremely powerful and reassuring, especially to writers who routinely bog down because they are truly convinced that nobody will want to read what they are working on (and even the best and most well-established professionals have bouts of severe insecurity from time to time). Knowing that an editor has bought the thing can make a tremendous difference.

A deadline adds urgency.

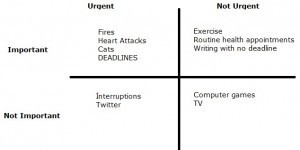

According to a lot of time-management gurus, the things we have to do fall into one of four categories: both urgent and important, important but not urgent, not important but urgent, and neither important nor urgent. In case someone has been under a rock and hasn’t seen the ubiquitous matrix, it looks something like this:

People tend to pay the most attention to stuff that falls in the Urgent column, whether or not it’s important, and then kick back with non-urgent, non-important stuff. That leaves important-but-not-urgent stuff like writing at the bottom of the list, after things like buying toothpaste (which may be urgent under some circumstances, but in the grand scheme of things is not terribly important by most people’s standards).

A deadline moves writing from important-but-not-urgent into the both-urgent-and-important box, if not immediately, then certainly as the deadline gets closer. That sense of urgency is what it takes to get a lot of people to quit reading their Twitter feed, livejournal, or Facebook (urgent but not important) and write.

A deadline limits available writing time.

This isn’t quite the same thing as urgency. There’s a quote from Gene Wolfe about writers who require specific environments, music, pens, etc. in order to produce, which ends, “A writer with only two hours a day in which to write can write in the back of an open truck traveling down the Interstate.” In other words, a writer who has a limited amount of time in which to write, and who knows exactly what that limit is, is less likely to waste any of it dithering or noodling around with trivia like which pen will be luckier today.

What it all adds up to is this: Having a deadline gives many writers the necessary reason to really focus, and it’s that extra level of focus that stimulates both productivity and creativity. If one can find another reason to focus (or muster the discipline to just do it) then the deadline isn’t really necessary.

January 11, 2015

Writing with a Day Job

Back when you were working a FULL TIME JOB (in finance?) what was your schedule like? Did you have to burn a lot of midnight oil, and come to work exhausted the next day? How did it feel and what tips might you have for those of us that are doing the same thing? (Bruce Wayne during the day and Batman at night).

It is exactly thirty years come March that I left my FULL TIME JOB (yes, in finance – I was a corporate financial analyst for what is now Target Corporation), so my memories are of a distinctly different time and place. No cell phones, let alone smartphones; no Internet; hardly any email, certainly no social media; no flash drives. That’s the first thing you need to know, because the upshot of all this was that it was impossible to use my corporate desktop terminal to write on, because the software was completely incompatible with my home computer, even after I switched from the Apple II+ to a PC, and even if they’d been compatible, there was no convenient, mostly-unnoticeable way to get the information from one machine to the other.

The second thing you need to know is that I am not a night owl. Even then, I found it hard to stay up past 10 p.m., and almost impossible to be coherent after 11. Once in a great while, I was on a hot enough streak to keep going beyond my usual falling-into-bed time, but that was rare – like, happening twice a year rare. If that. I am also not a lark, except by comparison to my current full-time-writer friends who sleep until ten or eleven every morning. If I am getting up at 6 a.m., it is because that’s when I have to get up in order to shower, dress, eat, and get over to wherever I have to be (at the job, when I had a day job; at the gym, now that I don’t have a day job but do have a walking partner with a day job). Getting up half an hour earlier to write is right out, then and now.

What my writing schedule looked like back when therefore involved splitting the process into two parts. During the day, I had a 15-minute “coffee break” in the morning, another in the afternoon, and an hour for lunch. I spent those times (and the relatively few slow periods when there really wasn’t anything to do for half an hour) scribbling the next few paragraphs on legal pads in a nearly-illegible abbreviated semi-shorthand. When I started getting asked to go out to lunch with too many people, my writing time suffered significantly. Eventually, Pamela Dean (who worked half a block down the street, and who had the same problem with writing time and lunches) started having lunch together once a week, during which we sat and wrote instead of talking to each other, and that worked remarkably well for both of us.

When I got home from work, I would take the day’s production and type it onto the computer. Usually I did this after dinner, on the same day I’d written the stuff (if I waited two or three days, I often could not decipher my own abbreviations). As I typed, I changed, expanded, and revised. Even with the additions and changes, it seldom took as long to type in as it did to write the stuff in the first place (I was a reasonably fast typist). When I got to the end of the day’s production-so-far, I’d keep going until I started to slow down; at that point, I’d copy the last paragraph or so (by hand until I got a printer) onto the top of the legal pad to take to work for the following day. Then I’d go do laundry or dishes or whatever.

The long writing sessions I had at the computer were usually on weekends. I had enough life maintenance and social engagements that I didn’t usually manage to get a long session in on both Saturday and Sunday – sometimes it was one day, sometimes the other. I did not work to a specific writing schedule (every day at 6 a.m. or 9 or noon or whatever). I didn’t even work to a schedule on weekends when my time was theoretically mine to arrange all day. Something always came up. I could usually get in at least one two-hour session sometime during the weekend; it was a matter of always being on the lookout for time I could use to write in, and taking immediate advantage of it whenever it came up.

Working this way, I generally got between half a page and three to four manuscript pages written on weekdays – I think it averaged out at a little over one manuscript page per day. The down side was that I did not spend much time socializing with my fellow workers or hunting out the sort of extra projects one needs to do in order to advance in a corporate environment, which means that I was most definitely not on a fast track to promotion.

I did not regularly come to work exhausted from writing into the wee small hours. Quite apart from the not-being-a-night-owl thing, I was being paid to do a job to the best of my ability, and I’d have felt wrong if I’d deliberately fudged on my responsibilities like that day after day. I might have felt differently if my day job had been something like waiting tables that didn’t require a lot of mental acuity. There were, of course, days when I stayed up too late and came in tired and not entirely up to snuff, but most of those were due to having had a late-night gaming session, rather than writing. I find it a lot easier to stay up late if there’s more stimulation than that provided by letters appearing on a screen and the noise of a keyboard.

As for advice, my first piece is that whether you write at your workplace during lunch hour or not, you do not tell anyone there that you have ambitions as a fiction writer. People have all sorts of weird ideas about how writers work and what they are like. Once they get over the excitement of knowing a Real! Live! Writer!, they are extremely likely to assume that you will stop pulling your weight at the job, or that they will be appearing as recognizable characters in your next novel (complete with embarrassing personal information). This doesn’t always happen, but in my experience it has happened with a frequency depressing enough to advise very strongly that you don’t mention your writing at your day job, even if you are quite, quite certain that your boss would love the idea and never, ever penalize you for it.

The second piece of advice is, remember what’s paying the bills. The day job comes first, until you have enough of an “IQ” fund (i.e., enough in the bank that you could say “I Quit” without worrying about paying the bills for six months, minimum) that you don’t actually need it any more. Past that, it’s an ethical decision. My feeling is that the writing comes on your time, not out of time during which you are supposed to be doing stuff for your employer. If you can do the job and still write (say, you are on the midnight-to-8-a.m. shift on the 24-hour help line that nobody ever calls at 4 a.m., and really, all you have to do is sit there and listen), fine…as long as you do the job. Again, it’s an ethical decision, and some people draw their lines differently.

Actual writing advice – well, that depends in part on your process. Take a look at the kinds of stuff you usually do and/or that you have to do for this story. Usually, that involves stuff like research, notes/prewriting, outlining, first draft, keyboarding (if you don’t do your first draft on the computer), revising/editing/proofreading. Think about which of these things you can easily do on a coffee break or lunch hour, and which you can’t. Think about when you need to do them (research, for instance, usually comes early in the process of developing a particular story; revising, editing, and proofreading can’t happen until you have at least a draft to revise), and how you do them. If your prewriting involves handwritten sticky notes plastered all over a door and your research involves reading a book on Roman aqueducts, you may want to do the first at home and the second on your lunch hour.

Next, think about when you have time that is yours. At the office, you have lunch time and coffee breaks. If you have the sort of office job where everybody clears out at five, but your bus doesn’t come until 5:30, you can grab another fifteen or twenty minutes of writing time by stretching your day a little. (You can do this at the other end of the day if you are a lark, too.) You may be able to snag some time after dinner, or after the kids go to bed (if you have kids). Or you may only have kid-free home time during certain TV shows, or on alternate weekends when you trade babysitting with someone in the same boat.

Then think about which parts of your process – most especially writing drafts – would fit well in which bits of the time you have. Also think about where you can salvage time you are spending on things that aren’t terribly important, like checking your email every five minutes, reading Twitter or Facebook, playing computer games, watching TV, etc.

Finally, commit to writing during some of that time. Yes, you have laundry and dishes to do, phone calls you could make on your lunch hour, etc. Life maintenance will eat your writing time if you let it, and you are the only person who can keep it from doing so. Yes, you have colleagues to chat with during coffee breaks, and you really, really want to see what they think of the latest episode of “The Walking Dead.” Socializing will eat your writing time if you let it, and you are the only person who can keep it from doing so. If you want to write, you have to write. If you “don’t have time,” you are spending your time doing something else that you are treating as more important. Sometimes it is more important … which can mean anything from a family crisis to the minutia of raising a family to, well, anything that is more important to you than writing. If that last includes discussing yesterday’s news at the water cooler on your coffee break or always joining your friends for “happy hour” after work on Fridays, or never missing an episode of your favorite TV series, that’s your choice and you are entitled to make it. Nobody gets more than 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. Everybody else has exactly the same number of minutes, hours, and days as you do; those of us who are writing are simply spending them differently.

January 7, 2015

Back on the horse

To Our Hostess: If you’re still looking for topics, how about something on getting back to writing after one of those periods of stress that justifies dropping writing like a hot rock while you cope? You’ve touched on it in various posts about being stuck, but I was thinking of something specifically about coming back after a crisis: anything from how to know if you’re ready, to tips on getting back into the saddle.

Funny you should ask that. A week and a half ago, my 94-year-old father fell and broke a rib; I have been down in Chicago since, making tea, doing things that hurt when he tries (like picking stuff up off the floor), dealing with plumbing emergencies, and not getting any writing done to speak of. Now he’s recovered enough to handle things with minimal check-in from the sibling on the spot, so I’m headed home to catch up and get back on the writing horse. So the suggested topic is…pertinent, to say the least.

First off, I’ll grant you that a week isn’t much in the grand scheme of things. This kind of emergency does, however, mean a total shift in mental focus; the difference between a one-week time off and six months or more is one of degree, not of kind. Coming back to writing after months away takes longer, but the steps are the same.

The first thing one has to do is accept that no matter what one’s intentions were, one has spent X amount of time not-writing. Yes, you planned to get up early and write a page before plunging back into crisis mode, or maybe grab a notepad during lunch break, or do fifteen minutes of journaling before you went to bed. You didn’t. You couldn’t. Stuff kept happening, and it wasn’t your fault. Other stuff was more important. So don’t beat yourself up.

Also, don’t expect to hit the ground running at the same speed and intensity you were working before the crisis. Sometimes, if the crisis went on long enough, some writers find that they sit down and all sorts of things come out in a glorious rush, like water rushing out of a dam when the flood gates are opened. If you are one of those writers, great; take advantage of it as much as you can. Just don’t count on it, because for most of us, getting started again is more like trying to run water through a backed-up drain – the blockage has set and hardened from lack of use, and it is going to take time and work to clear it out before things will flow properly again.

What I do, coming off one of these incidents, is to start off easy. If I was in the middle of a project before the handbasket whisked me off, I spend a while gearing up again. I do a sort of quick-and-dirty version of starting a project from scratch: I spend a few days or a week rereading my research notes (and any particularly important research). I go over my plot outline(s) and any notes about characters or background. I redraw or extend maps, if I have any; if I did any charts of the plot or character relationships that have gotten messy as I changed my mind about how things will go, I re-do them so they are neat and up to date (and fresh in my mind).

Eventually, I almost always end up revising the plot outline. I also reread and tinker with the already-written part of the project. And every time I do, I take a look at the end of the file, where the story isn’t moving forward. Sometimes, I add a sentence, but I don’t worry too much about pushing it. The point is more to remind my backbrain where it is going to be moving on from than to actually start moving.

Somewhere in here, I start generating random ideas that may belong in the story somewhere eventually – snippets of scenes, random bits of witty dialog, jokes, telling bits of characterization. Mostly, they’re only two or three lines long. They go in a “notes” file, which I also fiddle with, rearranging bits to group things together that seem to belong – sometimes because they feel as if they ought to be in the same scene, sometimes because they all deal with the same character or plot point. The idea on the top of my head is to be able to find them easily if I need them; really what I’m doing is, again, reminding my backbrain that this is the kind of stuff we are trying to do and this is where we left off.

The other thing I do is to try to do at least something – looking over research, reviewing notes, writing a sentence or two – every day. Even if it’s just opening the file and reading a page, and not actually writing anything, it helps get the habit back. I find it easier to be strict and get back to the something-every-day habit (even if it’s just reviewing notes), and then either expand to lots-every-day or else back off a little, than it is to have a little writing session once a week, and try to move to two a week and then three a week. Some writers get better results by starting with a session once a month or every other week, and adding more sessions as the urge comes back.

What I look for is the return of the urge to write. This does not happen if I try to force it; you cannot make yourself want something. If one watches too closely, trying to interpret every little thing as an increase or decrease in the writing urge, it won’t happen. It’s like planting a seed and then digging it up every five minutes to see if it is sprouting yet; you end up interfering with the natural process and making it less likely to work. One has to plant the seed and then get on with boring stuff like weeding and fertilizing and watering occasionally, and perhaps prepare ground for other seeds, or just dream about what the seed will grow into when it’s a mature, blooming plant, while trusting that down in the darkness, things are happening even if you can’t see them. Backbrains run on trust.

This description sounds a lot more organized and deliberate than it is in practice. I don’t have a procedure for getting back in the saddle after a crisis or a dry spell, though looking at this, I could probably develop one fairly easily (and I almost certainly should; I suspect it would be invaluable). What I’m doing here is thinking about what happened during and after various emergencies in the past 30 years, and trying to describe what I recall of how things worked for me. In thinking about it, I can say that sometimes the entire process has taken about five minutes, starting with reviewing notes and ending with me typing away furiously on the next scene or chapter; other times, it has taken weeks or months. It doesn’t seem to depend on the length of the crisis so much as it is related to the degree of emotional drain; when the tree came through my roof, it took a week to deal with all the practicalities and about five minutes to start writing again, while certain family news took five minutes to hear and two weeks to finish processing and get back on the horse. Which will, of course, vary depending on the writer. As always, it depends.

December 24, 2014

Christmas Break

Merry Christmas and Happy Whatever-You-Celebrate to all! I’m taking a two-week break for the holidays; your next post will be January 7.

December 21, 2014

Ideas and plot-noodling

Deep Lurker wanted to know what my ideas look like when I come up with them, specifically whether they’re just concepts or whether they have skeletal plots attached. Unsurprisingly, the answer is “It varies.” The slightly longer answer is “It varies A LOT.”

To give you a more specific idea of the range I’m talking about, Talking to Dragons started as just exactly that: the title and nothing else. At the other end, Snow White and Rose Red started with Terri Windling asking for an adult retelling of my favorite fairy tale, and me saying “I want ‘Snow White and Rose Red’ and I’m going to set it in Elizabethan England,” which certainly had a general plot attached (courtesy of the fairy tale and setting).

Every book is different. Every idea is different. Some come with plots attached, some don’t. Some are plots, and need characters and settings generated. It doesn’t really matter; what matters is whether the thing I come up with makes that spider-sense tingle, the one that tells me “I want to know more about this; I want to find out more about these people, this place, why and how this happened, what is going on.” When I say I can come up with five or six ideas in a couple of hours, I mean five or six that I want to write. I can come up with a whole lot more ideas than five or six, but most of them aren’t things I personally am interested in writing about. This is why I like plot-noodling for other people; it lets me generate lots of ideas that I feel no obligation to save or write about myself, that someone else can use.

The hard part is not really generating all this stuff; it’s forcing oneself to take the time to do the generating, and to make sure that what one has come up with is reasonably solid and interesting. Accepting the first character who auditions for the central role in your cool plot, or the first screenplay that comes along for your wonderful characters to play in…well, once in a while it works brilliantly, but you can’t depend on that. Most of the time, the first character who shows up turns out to be rather cardboardy and stereotypical, and the first plot either requires your wonderful characters to do things they simply wouldn’t do, or else is clichéd and doesn’t give them a chance to shine, or is full of holes.

Of course, some writers have a process that requires them to write something about their people or situation or idea in order to get it properly fleshed out. They have to write their way into their ideas, and while they grumble just as much as the rest of us when it all falls apart in the middle, their process almost requires them to write half a book or a hundred-and-fifty-page “draft zero” – it’s how they go about really digging into the idea, the situation, the characters, whatever the story-seed is. Once they’ve done that, then they can sit down and figure out the real story they want to write.

Me, I find it annoying to have to throw away seven or ten chapters and rewrite; I’d rather put the work in up front. How I do the work…well, let me come up with something and show you.

So what I came up with, after a couple of minutes, was “Girl unexpectedly inherits something magical.” The first thing I want to know is, “What is the magical thing?” I start thinking of physical objects: a cauldron of plenty? A cookbook of magical recipes? A magic carpet? A wishing ring? Aladdin’s lamp? Or maybe it’s an animal. Cats are the obvious first choice; too obvious. Dogs…no. Birds…birds? A mynah bird? Or maybe a parrot…African Grays are scarily intelligent even without magic being involved (as far as we know).

Next, who’s the girl? How old? I’m thinking mid-twenties, old enough to be out of college and on her own, and to have elderly relatives who could leave her something interesting without their deaths necessarily being a huge unexpected traumatic event (since that’s not the story I want to write; somebody else might make a different choice). But I feel no particular urge to write contemporary fantasy. So when is this happening? Is it even set in our world? I can see it going two ways: either as a “secret history” story set in real-life past, or in an alternate universe where magic is out in the open. Since I’m not sure which I like better, I’d normally noodle around with both of them for a while until one of them felt more interesting.

In this case, I’m imagining a large Victorian-style house, so I’ll go with AU Victorian-era. That makes me think of Dickens and Oliver Twist, which immediately changes my protagonist to a much younger person, early teens probably. So now I have an impoverished Victorian-era teenaged girl, and a potential plot (I could combine Oliver Twist and Bleak House for the inheritance part). I’m not happy with the Dickensian remake, though, so I look back at the other things I’ve considered. An impoverished Victorian girl inherits a magical African Gray parrot…what can it do for her? Where have I heard that question before? Puss in Boots…and there is the plot I want to start with.

I say “start with” because Puss in Boots will not transplant easily to the Victorian era, plus I don’t think my parrot is going to act quite like Puss. The plot will also change depending on the social setting and the magic, on who the girl inherited the parrot from and why, and a bunch of other things. Also, I can’t imagine that nobody knows the parrot is magical, so there are likely other people who are interested in getting their hands on it. Right now, everything is still pretty flexible – if something comes up that “feels right,” like the Victorian house and Oliver Twist, I’ll happily change everything else to fit, the same way my heroine went from being a post-college mid-twenties young woman to an impoverished young teenager.

All of this took me about half an hour, and it is a good solid story-seed. It still needs a lot of work and development before I’m ready to write – names for characters, more specifics about the background and backstory, more characters (each of whom will alter the potential plot, because each will have his/her own agenda), and a decision about the central story problem (is this fundamentally going to be rags-to-riches, or will it be finding out who killed the person who left her the parrot? And I didn’t know til I wrote that that it was murder, so things are still developing…). (And no, this isn’t what I’m currently working on. Maybe later.)

Coming up with a decent preliminary five-to-ten page plot summary from this will take me somewhere between two or three days and two or three months, depending on how much juice the idea has, how much time I have to really focus on the story and play with different possibilities, and normally I wouldn’t start writing until I have one (there have been exceptions to this – as I said, every book is different).

December 17, 2014

Terror and dreams

Still with the process questions, starting with “What in the writing process TERRIFIES you (gives you bouts of anxiety)…and how do you push through it? For example, a blank page is both terrifying and exciting at the same time…”

I think I spent ten minutes staring at that question, trying to formulate an answer more coherent than “What?” Because I have a hard time imagining writing being terrifying. Climbing cliffs is terrifying; hearing the phone ring and having the first words be “Your mother had a stroke last night and is in the hospital” is terrifying; spinning out on an icy freeway overpass when I didn’t know whether I was going to go over the side onto the lower freeway or slam into the cement median is terrifying.

Writing? Does not compare in the slightest. Because those other things have serious real-life possible consequences ranging from emotional trauma to serious injury or death. The only consequence of screwing up a scene in my writing is that I’ll have to rewrite the scene. Or possibly the story won’t sell. Absolute worst case is that the story does sell and the editor doesn’t point out that the scene needs to be redone and the thing will be published and I’ll be embarrassed in public. But it isn’t like I’m a surgeon; babies won’t die if I mess up a scene, a story, or even an entire novel.

(Um. Just so you know: I didn’t fall off the cliff, but I’ve been nervous about heights ever since. Mom died peacefully at home three weeks later. The car managed not to go over the guard rail or hit the cement barrier; I ended up in the center of the freeway in the narrow space between the barrier and the traffic lane, facing the wrong way. I spent about five minutes watching everyone coming in my direction figure out what had happen and slow down before they got to the black ice, and then there was a break in traffic long enough for me to get turned around and drive on. Trust me, writing doesn’t even come close.)

There are some things that I refuse to get wrong, but the idea of writing about them doesn’t terrify me. I don’t have to write about them if I don’t want to; I am perfectly capable of setting a story aside if I don’t think I can do a proper job of handling something, or if I’ve written it and, upon examination, it doesn’t do justice to one of those touchstones. There are a couple of things that have been in the to-write stack for years waiting for me to have the chops to write that particular story the way I want to write it.

It might be a problem if everything ended up in the “I’m not a good enough writer yet” stack, but I am also wonderfully stubborn about some things. If I think I can make something work, and all my test readers say it isn’t working, I badger them until I think I have a theory about why it isn’t working, and then I go off and rewrite it. Lather, rinse, repeat, until it does work.

There are also some things that I dislike writing. This is not the same as having an anxiety attack; I’m perfectly capable of writing council scenes and transition scenes, but I dislike doing them. A lot. I also turn out to have a really deep desire not to write contemporary-setting fantasy, which I didn’t know until I sat down to write the first few chapters of the current WIP and realized that if my characters didn’t get out of here a lot faster than that I was going to start throwing things or break my computer or something. Even so, it was basically a matter of a) cutting things back to make that part as short and tight as possible and b) buckling down and writing it so I could get to the fun stuff.

Next: idea sources. I have plenty of dreams, few nightmares, and no, they don’t end up in the books. They tend to be long and convoluted, and either they make no logical sense when examined upon waking, or else they are intensely boring, like the one that had about ten people arguing about how to purify the water supply in a cave. Boiling or chlorine tablets? Or the ceramic camping filter? Or the Rube-Goldberg contraption somebody whipped up? Or ordering from the survivalist catalog somebody else had? With endless technicalities and nobody ever getting around to making a decision.

Trust me, this would not make even a good scene, much less a decent story idea. I might be able to do something with the reason all those people were sitting around a cave arguing about the water supply, but I’d have to come up with it; it wasn’t part of the dream. And frankly, they weren’t interesting enough for me to want to write about.

I was going to go on some more about ideas, but the post nearly doubled in size and I wasn’t even half done, so that’ll be Saturday.

December 14, 2014

Fermentation

I suspect that I shouldn’t have been surprised when my request for blog topics netted several about my process and career, but I was. The first one I’m going to deal with was about letting projects “ferment” and its implied negative effect on productivity and the writer’s finances.

In order to explain how that works for me, you probably need to know a couple of things. The first one is that I’m inconsistent. Every book’s process is a bit different. For instance, I usually have an outline, which I proceed to ignore, but at least five of my books don’t fit that pattern: Talking to Dragons had no outline and no plan until nearly two-thirds of the way through and neither did Sorcery and Cecilia; the three Star Wars novelizations had what might be termed an extreme outline – I had a 120 page script for each book which I had to follow.

Next, I’m usually a one-project writer. Still, I wrote the first four or five chapters of The Seven Towers alternately with the first four or five of Talking to Dragons – and when I say “alternately,” I mean that I spent one week working on the first book and the next week working on the second, then back to the first. It worked for me then because the process was very different for the two: for Seven Towers, I was still in the making-things-up-and-nailing-them-down stage, which requires frequent pauses to think. Talking to Dragons, on the other hand, was just showing up; it needed pauses, but I couldn’t do anything in the pauses because I didn’t know what was going on.

That back-and-forth rhythm only worked for the first four or five chapters, though; I couldn’t maintain the constant shift in focus beyond that. Also, Talking to Dragons took off, and Seven Towers needed some attention to get unstuck, so I set the second book aside, finished Talking, and then went back and picked up Seven Towers some eight or ten months later. I’ve never been able to keep two book manuscripts going at the same time for more than a couple of chapters. Even when I’ve been hit with a must-write short story idea, it generally means setting the novel aside for a few weeks while I focus on the short piece (fortunately, this only happens about every five years or so).

For about the first twelve years of my career, I finished everything I started, though not necessarily all in one go. There were a couple of time when I started a book, got halfway through, and then had to stop and work on something else because of circumstances or to take advantage of a can’t-pass-it-up opportunity. Mairelon the Magician is an example of that; I got a good chunk of the book written, and then the Letter Game came along and took over my life for three months and turned into a novel. By then I’d realized that I didn’t want to sell Mairelon to my then-current publisher, but they had an option on my next book. So I wrote them something I thought they’d like, which took more time, and in the end it was a couple of years before I got back to Mairelon and finished it.

That sums up my answer to the question about letting my stories settle or ferment: either the story is actively getting worked on and the “fermenting” takes at most a week or two, or else the story has been placed in storage, where I expect it to stay for a year or more before I get back to it. In the former case, the intermediate non-writing weeks are part of my normal writing process, and I’m noodling at the story constantly. In the case of half-done things in storage, there’s a reason they’re there (beyond “Oh, gosh, I’m stuck”) and I immediately start working on something else. It’s part of filling the pipeline.

Writing can be looked at as a series of very long pipelines. People sometimes recognize the last and most obvious: when you sell a book to a publisher, it can take years to work its way through the editorial and production processes. Ideally, one continues writing and selling things, and eventually they start coming out the other end of the process. Other parts of the process work this way, too: when one is trying to get published and/or establish one’s career, for instance. The most successful writers I know wrote their first manuscript, put it in the submissions pipeline, and immediately started writing their next ms. Some of them had four or five books under submission when the first one finally got to the other end of that pipeline and an editor bought it.

For some writers, writing works the same way. I know a number of writers who really can’t focus on more than one story at a time at all. They have a hard time coming up with stories they want to tell, and once they have one, they relax with a sigh and don’t generate any more ideas until they’ve completed the one they’re working on. I, on the other hand, can generate five or six interesting ideas for possible books in a couple of hours, tops. I used to be able to keep this tendency under control, but some time in the 1990s it got loose and now there’s no keeping up with it. Some of the stories need working on before I can see whether they’re interesting enough to finish; some of them stall when they need some heavy-duty research that I don’t have time to do; and there are a few that I started and then realized I didn’t have the chops to do justice to. So those are all partials sitting on my hard drive, and I revisit them occasionally between books to see if any of them are ready to get written the rest of the way yet. If one of them is, I have a big jump on getting the next thing started.

The “fermenting” is only a financial problem if it takes a long time and one cannot produce any other pay copy in the meantime (or can’t produce it fast enough to keep the publishing pipeline filled) and one is in a position where one is depending on that steady income. Otherwise it’s only a problem of patience.

December 10, 2014

Attitude

I feel like I keep coming in fourth at the Olympics. – Tiana Smith

Trying to break into publishing is a time-consuming and deeply discouraging process. It always has been. There is little that can make someone feel as unappreciated and untalented as a string of form rejection letters.

And there is nothing you can do to change that. (You can opt out, i.e., self-publish, but that isn’t the same as changing the submission process. It’s doing an end run around it…and you need to be very good at running for that to work, but that’s a whole different post.) When you have a publishing industry that generates approximately 600 SF novels per year, and (judging from the self-published stuff I see on the Internet) hundreds of thousands of people writing stuff they hope will get one of those 600 slots, it is going to take a while even if you are good at what you do.

This is what being a professional writer is about. And it is not just a problem for first-time novelists. I don’t know any professionals who have not been turned down by an editor, some of them quite nastily. And that includes some writers who have been making a living at this for decades, and/or have won awards ranging from minor to major.

Even after you have an established career, there will be times when the book you are excited about writing evokes no tiny spark of interest even from your agent, let alone an editor. There will be times when the agent you worked so hard to get tells you (gently or bluntly, depending on her style) that the cool, clever thing you just produced is unsellable, just like the last two, and unless you give her a proposal that has some possible sales, she’s going to have to stop representing you. Some of those times, she will even be right about the unsellability.

If you are going to have a writing career, you have to learn to deal with it.

So how do you deal with it, Ms. Wrede?

Everybody finds his or her own way of dealing with the emotional roller coaster that is writing. Some bury their heads in the sand, some get deeply involved with the minutia of their careers, some self-publish. The thing you have to remember is that no method is perfect. Sooner or later, something will get through whatever wall of reassurance you have erected, at which point, you simply have to tough it out until the wind changes and you claw your way out of the Slough of Despond.

I realize that this does not sound helpful or reassuring. So here are some things to consider:

Why are you doing this writing thing, anyway?

No, don’t start with the easy, flip answer. Dig for the real one, and be honest with yourself. I doubt that many long-time readers of this blog are mainly in it for the status or the fame or the money (ha!), but if there happens to be someone for whom that is their primary motivation, I recommend that they sell everything they own, move to Los Angeles, and try to become a movie star. Their chances of getting what they really want are a whole lot better that way.

That leaves everybody else. There are still lots of different reasons for writing, though, and it can help to know which one is yours and how it fits with your other motivations. (And you have other motivations, or you wouldn’t be asking this question.)

Me, I tell stories. I’m fortunate enough to be able to make a living from it, but if I couldn’t, I’d still be telling stories to somebody, even if it was just my cats. I write them down in order to clear out my head so more stories can come in without making my brain explode. I try to write them well because a) I think my stories deserve the best and b) I am a horrible perfectionist about everything.

That’s why I write. It doesn’t have anything to do with selling, please note.

So why are you trying to break into publishing?

There are a bunch of possible reasons for this one, too, but the thing to notice is that this is where the status and fame and money parts come in, and also success/failure. If they didn’t, Tiana’s nice analogy wouldn’t strike that resonant chord that it does in all of us (yes, me, too). From a rational perspective, publishing has a lot of advantages in terms of production, distribution, and publicity – yes, some of those advantages are less in this age of ebooks and the Internet, but a lot of them are still there to at least some extent. But you almost never hear writers talk about publishers in terms of what they can do for a book that the writer can’t, which leads me to the obvious conclusion that most writers are motivated by something else in this regard.

The important thing here is that unless you are one of those people who really ought to go to Los Angeles and get into movies, breaking into publishing is not why you write. It is secondary. This is useful to remember when one is facing a string of publishing setbacks.

How will you know when you are a success as a writer?

Many of the writers I’ve known never think much about this part. The publishing system has all sorts of ways of measuring how writers “succeed” or “fail” – size of advance, sales, reviews, movie deals, awards, bestseller lists, critical acclaim (which is not quite the same as reviews), length of time in print. And, of course, whether you can “break in” and be bought by a traditional Big New York Publishing House in the first place.

Unfortunately, none of these things is universally recognized as the measure of success as a writer. You pretty much have to decide for yourself what “success” means – a six figure advance, even if the sales tank and the reviews are terrible? Great reviews, even if the advance was miniscule and the sales mediocre? A movie option, even if the movie is never made? Huge, bestseller-level sales even if the critics pan the book and the movies won’t touch it?

I’ve watched a number of writers come to grief because they never stopped to think past “I want to get published” as their criteria for “success as a writer,” with the result that even after they sold and had solid mid-list careers, they were never happy with what they had. Nobody ever gets it all – the advances, the sales and bestseller lists, the movies and the awards and critical acclaim. There’s always a piece missing, and if you don’t know how you define writing success, odds are good that you’ll be unhappy because you’ve focused on what you haven’t got instead of what you’ve achieved. Others will congratulate you on your bestselling book, and you’ll glower because the movie option fell through, or you won’t enjoy the critical acclaim because the sales weren’t all that you expected.

The real trick is that you do not have to use any of these metrics to define your success. You get to decide. I define “success” as writing a book that is close to the story I envisioned, written to the absolute best of my ability. Consequently, I have written books that sold well but which I am not happy with (there’s a flaw that only I can see) and books that I am extremely happy with in spite of the negative reviews they occasioned. It doesn’t make me happy with the bad reviews, but it keeps them in perspective. Actually, I rarely read reviews of any kind – I don’t see the point. I can’t do anything to fix whatever they think is wrong with the book, because by then it’s in print, and if they like it, well, that’s lovely, but so is a day at the beach. I’m not going to get exercised about it.

The other thing I do is compartmentalize. Writing books is what I do, and I would do it whether or not I got them published. Getting published is my career and my business, and I have to pay attention to it, but it’s a different sort of attention, and how my business is doing does not reflect on my worth as a person or my success as a writer. It’s a completely different thing.