Jeanne Gehret's Blog: http://SusanBAnthonyFamily.com/, page 11

April 3, 2017

Posse Hunts John Brown

Why was D.R. Anthony so fiercely abolitionist? Events such as the following would have fueled his anger. Today’s post gives us a typical example of how proslavery forces treated John Brown, an antislavery man whom Anthony revered and probably knew. (D.R.’s brother Merritt had fought with Brown several years earlier in southern Kansas.)

Living only 25 miles away from the following tense encounter between a proslavery posse and Brown, Anthony might have stood with the guards who protected the famous hero. Even if Anthony didn’t, he certainly would have followed the news with as much anxiety as did New Hampshire emigrant Julia Louisa Lovejoy, whose letter back east gives us this riveting account.

For the death of John Brown, the Missouri governor and others offered $5,500. Lured by this “bait,” Lovejoy reported, a pro-slavery posse headed by Marshal J.P. Wood tracked “our champion” (Brown) to a cabin where the abolitionist holed up with a dozen African-Americans.

This cabin he had strongly barricaded, and told his pursuers “he would never yield, neither would he be taken alive.” The Marshal and his force surrounded the cabin and ordered Brown to “surrender!” Brown replied, “Come and take me.” The officer dared not undertake the job, and one hundred more like him could not capture those indomitable spirits that well knew what would follow if they were taken prisoners.1

A stand-off occurred. Brown’s group, armed with Sharpes rifles, was guarded by a company of twenty-five antislavery supporters. Giving voice to the bodyguard, Lovejoy wrote, “Take care, sir, if one gray hair on that venerable head is singed, your whole party will be riddled with balls!”

The Marshal’s posse sent for reinforcements to Atchison (about four miles away) and rumored that two cannons would soon arrive to explode the cabin. In an oddly turned phrase, Lovejoy wrote that United States Army troops who engaged in “pretended pursuit” seem to have sufficiently distracted the posse, during which time:

Brown sallied forth and took three of the Atchison men prisoners (one of them, it is affirmed, he recognized as the miscreant who shot his own son, F. Brown, at the “Ossawottamie battle.”) He also took four of their horses that they had secreted in the timber, and then with his freed slaves and party pulled for Iowa, taking prisoners and horses along with him!

Thus Brown escaped from Kansas in February 1859, just eight months before his fateful raid on the arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, WV. In a summary of this western event, Lovejoy correctly predicted the manner of Brown’s death, saying, “We fear now that Brown and his party will be intercepted by an overwhelming force, but he cannot be captured alive.” “

Photo courtesy of Kansas Historical Society

Bell, Sarah. “Lovejoy, Julia Louisa” Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Mar, 31, 2017 at http://www.civilwaronthewesternborder...

March 31, 2017

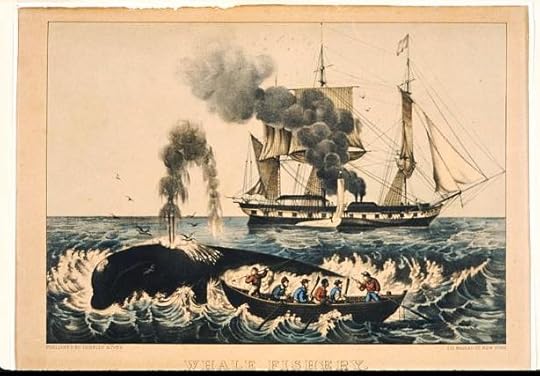

Women Whalers

It’s been awhile since we’ve spoken of Annie Osborn Anthony, daughter of a whaling captain from Martha’s Vineyard and eventually the wife of Daniel Read Anthony. Today’s post references her sister-in-law Lucy Hobart Osborn, who will represent dozens of women who accompanied their husbands in worldwide voyages in search of whales.

In the foreground of the photo above you can see a whaling crew attacking a sperm whale, the species that provided oil prized as an illuminant and lubricant. Seen through 21st century eyes, hunting this giant mammal is an ecological crime. (No doubt they were hunted almost to the point of extinction.) But seen through a 19th century lens, whale hunts filled a need as much as today’s natural gas drillings or Texas oil wells.

Before electricity, sperm oil was used to heat buildings and later, became an essential component of sewing machines, watches, and even locomotives. When its use was outlawed in the automobile industry in the 1970s, the number of transmission failures doubled.

It’s little wonder that Annie Osborn did not want to marry someone who attacked these giants to harvest sperm oil. Whale hunting was a dangerous, smelly, messy process that involved absences of up to five years from home. Voyagers suffered weather hazards and, in the case of the Ocmulgee captained by Annie’s brother Abraham, Confederate pirates. Nevertheless, Lucy Hobart Osborn accompanied her husband on many voyages and, according to the book Whaling Wives, was quite the navigator.

Abe Osborn captained a whaler named the Osmanli on a voyage in 1878, accompanied by Lucy and their daughter Annie. (Was the child named after her sister-in-law Annie Osborn Anthony?) Here is an account of their narrow escape from the sea near Mexico, beginning with a report from the Whalemen’s Shipping List from New Bedford:

“Osmanli got into the breakers at Altata, 160 miles north of Mazatlan, March 8, and became a total wreck. The crew lived on the beach two weeks and gained a scanty subsistence until the schooner Eldorado took them to Mazatlan. The men complain that Captain Osborn left them there to shift for themselves . . . .”

“Abe Osborn had not only the responsibility for the vessel and the crew but for his wife and daughter. One may only guess how he tried to cope with the situation, and how he got Lucy and Annie safely to the beach, probably in fog….”1

Lucy and Annie did not sail with Abraham again. Later, when Abe voyaged on the whaler Orca, mother and daughter met him in Boston.

Photo from Library of Congress

Emma Mayhew Whiting and Henry Beetle Hough, Whaling Wives, p. 239.

March 29, 2017

Enter Free Book Giveaway!

Two readers who enter a Goodreads contest will win a free copy of The Truth About Daniel. Click here to enter the contest, which runs from March 29-April 6.

Two readers who enter a Goodreads contest will win a free copy of The Truth About Daniel. Click here to enter the contest, which runs from March 29-April 6.

Not familiar with Goodreads? Here’s how they describe themselves:

…a free website for book lovers. Imagine it as a large library that you can wander through and see everyone’s bookshelves, their reviews, and their ratings. You can also post your own reviews and catalog what you have read, are currently reading, and plan to read in the future.

Besides all those bookworm activities, you can also sign up for free giveaway contests! They handle everything confidentially, and their site is secure. Give it a try!

March 28, 2017

Spymistress Elizabeth Van Lew

Today’s blog on one of my most-admired American women features my favorite historical novel (pictured) as well as a quiz on spies!

Today’s blog on one of my most-admired American women features my favorite historical novel (pictured) as well as a quiz on spies!

During the Civil War, Union Spy Elizabeth Van Lew lived in Richmond, VA, the very heart of the Confederacy. A wealthy churchgoing woman, she cited simple compassion for prisoners as her reason for visiting Libby Prison, six blocks from her home. Meanwhile, she was was exchanging valuable war secrets disguised in the soles of shoes and casserole dishes with secret compartments.

Even her rebel sister-in-law and neighbors did not realize she was against the politics of her city.

With nerves of steel (just like my March 16 blog heroine Beulah Vanderhoop), Van Lew managed a spy ring that included a servant in the most dangerous place of all—the home of the Confederate president. In her later years she was shunned by Richmond society and after her death, her mansion was burned, perhaps for spite.

For one of my favorite historical novels entitled Spymistress (by Jennifer Chiavarini), click here. Chiavarini’s style in this book inspired the writing of my historical novel of the same era, The Truth About Daniel.

For a factual account of Van Lew, click here.

And finally, watch this great video and take this quiz to identify female spies!

March 23, 2017

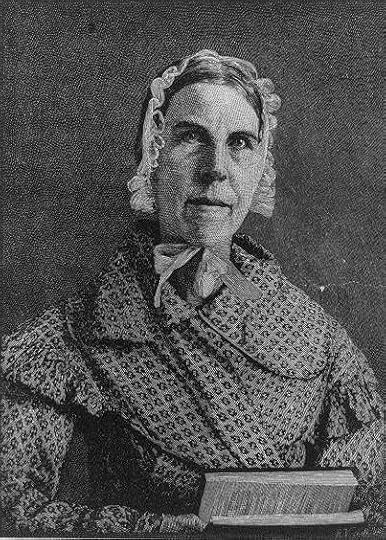

A Woman Alone

Like D.R. Anthony, Clarina Nichols emigrated to Kansas in 1854 with one of the earliest parties Emigrant Aid Company. By the time Nichols set foot in Kansas, D.R. had already returned to his home in Rochester, NY to save money for permanent relocation in Kansas. D.R. gave up (temporarily); Clarina stayed.

Like D.R. Anthony, Clarina Nichols emigrated to Kansas in 1854 with one of the earliest parties Emigrant Aid Company. By the time Nichols set foot in Kansas, D.R. had already returned to his home in Rochester, NY to save money for permanent relocation in Kansas. D.R. gave up (temporarily); Clarina stayed.

Both made the journey in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which decreed that citizens of the new territory should determine whether the state entered the Union as a slave state or free state. The state was then a rough frontier, and in one letter Nichols described ten thousand rowdy pro-slavery Missourians storming the Kansas polling place and preventing antislavery voters from casting their ballots.

Nichols wrote many letters to eastern newspapers, cheerfully describing the austere conditions in Kansas and noting that most of the male emigrants who abandoned Kansas did so because they could not keep house and farm at the same time. She, however, was forced to do just that when shortly after moving to a remote, pro-slavery area outside of Lawrence, her husband and adult sons died leaving her among political enemies and needing to homestead by herself.

Not only did she want to fight slavery in the territory, but she hoped that the new state would have a more open mind on women’s rights. She addressed numerous legislatures in Wisconsin, Ohio, and Kansas, declaring that women should either be allowed to vote or excused from taxation. She was responsible for gaining women the right to vote in the school elections of Kansas in 1860 and many other gradual victories. Always, her ultimate goal was for woman suffrage.

Much of her devotion to righting the wrongs of married women comes from her three marriages, especially the first to fellow Vermonter Justin Carpenter. Moving around New York State, Carpenter depleted his wife’s dowry, had an irascible and erratic temper, and tried to kidnap the children. Nichols’ family prevailed upon state legislators to modify divorce laws and, in the late 1830s, she was allowed to leave Carpenter behind. Nevertheless, she was psychologically wounded and financially depleted. It was during those early years that she began a long career of newspaper correspondence and publishing, at first creating a humorous pseudonym Deborah Van Winkle, an outspoken Yankee who spoke of “wimins wrongs.”

For information about this foremother I am indebted to Kansas Historical Quarterly and American National Biography.

March 20, 2017

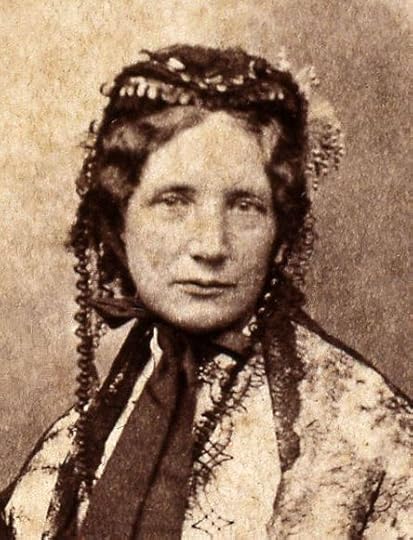

The Lady Who Made This Big War

That is how Abraham Lincoln is said to have greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe when he met her many years after the publication of her shocking 1852 bestseller Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which gave slavery a face and a heart by telling it through the eyes of individuals. Read about Harriet, her book and its amazing success by clicking here.Even more popular than the book itself (which had sales in the 19th century second only to the Bible) were the stage renditions of her play.

That is how Abraham Lincoln is said to have greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe when he met her many years after the publication of her shocking 1852 bestseller Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which gave slavery a face and a heart by telling it through the eyes of individuals. Read about Harriet, her book and its amazing success by clicking here.Even more popular than the book itself (which had sales in the 19th century second only to the Bible) were the stage renditions of her play.

It is probable that the Anthonys of Rochester and the Osborns of Marthas Vineyard were familiar with Stowe and her work. Harriet’s family of origin moved in the same abolitionist circles as the Anthonys. And Josiah Henson, the man who upon whom Harriet based her novel, made a notable appearance at the Methodist Camp Meetings that were held every summer on Martha’s Vineyard; the Osborns would likely have seen the publicity. In addition, the stage rendition of her story was one of the most popular theatrical renditions of its era.

Of her most famous book, Stowe said:

As a woman, as a mother, I was oppressed and broken-hearted with the sorrows and injustice I saw, because as a Christian I felt the dishonor to Christianity–because as a lover of my country, I trembled at the coming day of wrath.

For another look at her family, her other literary works, and her later years, visit the website of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

March 16, 2017

Vineyard Woman with Nerves of Steel

Today’s heroine for Women’s History Month is Beulah Vanderhoop of Martha’s Vineyard, a maritime conductor on the Underground Railroad in the 1850s. She had the courage it took to assist as many as eight ex-slaves to safety and in my novel, profoundly affected Annie Osborn of Edgartown.

Today’s heroine for Women’s History Month is Beulah Vanderhoop of Martha’s Vineyard, a maritime conductor on the Underground Railroad in the 1850s. She had the courage it took to assist as many as eight ex-slaves to safety and in my novel, profoundly affected Annie Osborn of Edgartown.

Though Vanderhoop is firmly grounded in history, the details about her are many and somewhat conflicting. Depending on which account you believe, she was either full or half Wampanoag, a member of the Native American tribe who populated the Island long before white settlers. In a custom not uncommon on the Vineyard, she was married to an African-American from Surinam.

Vanderhoop is the woman elsewhere identified by The Vineyard Gazette’s September 29, 1854 account of two women coaxing Randall Burton out of a swamp near Holmes Hole (now Vineyard Haven) and taking him to her home on Gay Head (now Aquinnah)—a distance of some 15 miles; another account says that he was brought to her home on the Wampanoag settlement at the furthest reach of the island. One version has her sailing him six miles across Vineyard Sound to New Bedford, while another suggests that another tribal member did it.

Beulah welcomed Burton into her home and fed him. One can imagine his appetite after being nearly starved hiding for months in a Florida swamp, stowing away on board a north-bound ship for at least five days, and then hiding in the Vineyard’s swamp for three days. All accounts agree that his enjoyment of his meal was short-lived, however, for the pro-slavery sheriff did his best to gather a posse, paying $1 to every man who would help him hunt and recapture the fugitive.

Though the sheriff wanted to search the Wampanoag homes, he had to leave the settlement empty-handed and come back six hours later with a warrant. That delay was enough for some of the Natives to arm themselves with guns, pitchforks, and clubs against the sheriff’s return and for others to undertake the arduous crossing of Vineyard Sound and Buzzard’s Bay, which can involve difficult headwinds and dangerous shoals. For a modern account of such a crossing, as well as some beautiful photos, click here.

True to form, some accounts say that Burton moved on to Canada, while others say that he remained for seven years gainfully employed in New Bedford, just across the Sound from the Vineyard. Personally, I like the one that says that every year he visited Beulah to thank her.

Photo by Jeanne Gehret

March 13, 2017

When Susan Retired Her Red Shawl

Today we commemorate the death of Susan B. Anthony.

Today we commemorate the death of Susan B. Anthony.

According to Susan’s official biography, it was said that Washingtonians marked spring each year with two signs: the return of Congress to the nation’s capital and the return of Miss Anthony in her red shawl to lobby Congress.

In her later years, the shawl was such a beloved trademark that when she stepped up on stage without it one day the newsmen ribbed her that they would not file their stories unless she wore it. She sent someone back to the hotel to fetch it. Only death could stop the indefatigable Anthony.

In 1906 (her 86th year), after making an earlier-than-usual visit to the capital, she contracted pneumonia and died at home on March 13. On her deathbed, she seemed to greet a parade of famous comrades with whom she had worked for universal suffrage. Together, they had labored long and hard and accomplished much, not only for women but for African-Americans. Still, the most precious right of female suffrage eluded her. Holding up her pinkie, she said to her lieutenant, Anna Howard Shaw, “Just think of it, I have been striving for over sixty years for a little bit of justice no bigger than that, and yet I must die without obtaining it. Oh, it seems so cruel.”

The following is an excerpt from the New York Evening Journal’s testimonial upon Susan’s death:

No wrong under which woman suffered was too great for her to dare attack it, no injustice too small to enlist her pity and her attempt to remedy it.

She saw the tears of the slave mother with the child torn from her arms…and she was foremost among those who fought for freedom for the negro.

She saw women with great intellects starving for knowledge, and she fought to open the avenues of education to them. She saw the poverty of the sweat shop women..and she fought to better the conditions under which they worked. She saw the honor of the girl-child made the plaything of the debauchee, and she fought for laws for her protection. She saw the woman working by the side of the man for half the salary, and she fought for equal pay for equal work. She saw the intelligent, educated, tax-paying woman of the country classed by the law with the idiot, the criminal and the insane, and she died fighting, with her face to the foe, to have this monstrous injustice removed.”

Ida Husted Harper, Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, vol III. Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1908

Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian

March 9, 2017

The Scandal of Speaking in Public

The National Women’s History Project salutes “countless millions of women who planned, organized, lectured, wrote, marched, petitioned, lobbied, paraded, and broke new ground in every field imaginable, [making] our world…irrevocably changed. Women and men in our generation, and the ones that will follow us, are living the legacy of women’s rights won against staggering odds in a revolution achieved without violence.”

The National Women’s History Project salutes “countless millions of women who planned, organized, lectured, wrote, marched, petitioned, lobbied, paraded, and broke new ground in every field imaginable, [making] our world…irrevocably changed. Women and men in our generation, and the ones that will follow us, are living the legacy of women’s rights won against staggering odds in a revolution achieved without violence.”

For women’s history month, I have confined my selection of heroines to those who lived in 19th century America. That eliminates some of my favorite women like Alice Paul and Inez Milholland, who were both so instrumental in the second generation of suffragists that brought the movement through the final years before the woman suffrage amendment finally passed in 1920.

This is a special year for New York State, where women earned suffrage on state matters in 1917. Unfortunately New York State resident Susan B. Anthony did not live to exercise her right to vote legally in either her state or her country, for she died in 1906. Indeed, even though the entire country revered her late in life, her home state in 1894 ignored 600,000 petitions for woman suffrage, and the following year it formed an association opposed to woman suffrage. The only states that allowed women to vote in Susan’s lifetime were Wyoming (1890), Colorado (1893), Utah and Idaho (1896).

To offset this sad showing for New York State, today I am highlighting two female reformers who blazed their way across the empire state so brightly that they inspired the young Miss Anthony. They were Sarah and Angelina Grimke, who made themselves unpopular in their native Charleston by championing slavery, as memorialized in Sue Monk Kidd’s excellent historical novel The Invention of Wings. The sisters grew up as privileged daughters of a judge and plantation owner, with their slaves sleeping on the floor of their bedroom.

In an article about the sisters’ Charleston home, author Louise Knight also gives background on the economic dependence of that slaveowning city on slavery.

The striking elegance of the Grimké home reflected both the sophistication of the city they lived in and the family’s fabulous prosperity. Charleston in the early years of the nineteenth century was one of the new nation’s great metropolises. In 1810, with a population of roughly 24,711, it was the fourth largest city in the United States and possessed enormous wealth. The white community numbered 11,568. Charleston was a majority black city, with 13,143 Africans and people of African descent. In 1810, 89 percent of the black population—11,570 people—was enslaved, toiling in the households or the family stables or hiring out to work in the trades. Their unpaid labor across the city—combined with the unpaid labor of those working on plantations across the state—created Charleston’s wealth. The remaining 11 percent of the black population—some 1,430 African Americans—formed the free black community, whose skills in the trades and at the docks kept the city functioning.

Sarah and Angelina witnessed their mother’s arbitrary and cruel punishment of slaves in the “sugar house,” a place of such barbarism that its walls were soundproofed to muffle the screams of tortured persons within. Sarah taught her slave to read and would probably have been a lawyer had she been female. Angelina wrote a pamphlet entitled “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South,” in which she wrote:

I appeal to you, my friends, as mothers; Are you willing to enslave your children? You start back with horror and indignation at such a question. But why, if slavery is no wrong to those upon whom it is imposed? Why, if as has often been said, slaves are happier than their masters, free from the cares and perplexities of providing for themselves and their families? Why not place your children in the way of being supported without your having the trouble to provide for them, or they for themselves? Do you not perceive that as soon as this golden rule of action is applied to yourselves that you involuntarily shrink from the test; as soon as your actions are weighed in this balance of the sanctuary that you are found wanting?

Her pamphlet was burned in Charleston. Soon after, the Grimke sisters undertook a 67-city speaking tour of the Northeast (including New York), where they amazed crowds by addressed mixed audiences, not just women—a practice that was considered scandalous because the sexes were supposed to be kept separate and women were not supposed to speak in public.

Sarah and Angelina Grimke paved the way for Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and others to speak in public about abolition and on women’s rights, as well.

March 6, 2017

Half the Sky

Susan. B. Anthony.

Lucretia Mott.

Elizabeth Van Lew.*

Clarina Howard Nichols.*

Lucy Stone.*

Elizabeth Blackwell.* Clara Barton.* Elizabeth Ann Seton.* Antoinette Brown Blackwell.*

Their names sound like a litany on our lips, these 19th century American heroines. During this month of women’s history, we usually think of women like these who have risen above the throng.

But let’s face it: women have always held up half the sky. And there is another kind of history–the tales of women who feed, clothe and shelter us by the work of their hands and the sweat of their brows, whether they are paid or not. Women who, when we are weak, hold us while we weep and then strengthen us to stand on our own.

Unlike the “greats” in my first paragraph, these women are noteworthy because they are accessible to us in their ordinariness. They live in our homes or next door, give us medical care, serve on our parent-teacher associations, run our libraries, watch our kids, and own the businesses we patronize. They teach us to walk, write the books we read, and snap the photos that make our hearts sing or cringe. They run myriad small businesses so they can juggle family and work. They are our sisters, mothers, aunts, friends, and members of our worship communities. Because they are close to us, we learn much from their intelligence, wit, grace, beauty, grit, daring, and faithfulness.

In addition to her many iconic friends in reform work, Susan B. Anthony leaned on many such everyday women for food, housing, friendship, and funds during her years of campaigning for universal human rights. She was inspired by her Quaker aunt Hannah Hoxey and her mother Lucy Anthony. Her letters and her biography show that she stayed close to her sisters, sisters-in-law, and nieces, many of whom helped her with the mundane tasks that allowed her to live her public life.

I was greatly inspired by Susan when I was writing my 1994 biography of her. (I hope to re-issue it soon.) This year I published a book an ordinary woman, Susan’s sister-in-law Annie, who held up half the sky with Daniel Read Anthony. In doing so, I discovered greatness in little-known people.

If you believe Bill Wilson’s adage, ““To the world you may be one person, but to one person you may be the world,” then such little-known women of America are just as valuable as Susan B. Anthony.

Happy Women’s History Month. Remember to hold up your half of the sky. But when you feel your arms falter, look to the woman next door.

*If you don’t know some of these contemporaries of Susan, they are:

Elizabeth Van Lew, Union spy during the Civil War;

Clarina Howard Nichols, Kansas abolitionist and feminist;

Lucy Stone, women’s rights activist;

Elizabeth Blackwell, first woman doctor in U.S.;

Clara Barton, Civil War nurse;

Elizabeth Ann Seton, first American saint;

Antoinette Brown Blackwell, first woman minister in U.S.

http://SusanBAnthonyFamily.com/

or her brother Daniel Read (D.R.) Anthony. I share all of these on my blog. You can also get special insights into my new b Whenever I travel, I stop in to visit a site connected with Susan B. Anthony

or her brother Daniel Read (D.R.) Anthony. I share all of these on my blog. You can also get special insights into my new book The Truth About Daniel, based on D.R.'s romance and his rambunctious days as an original Kansas Jayhawker ...more

- Jeanne Gehret's profile

- 15 followers