Victor D. Infante's Blog, page 184

January 3, 2011

Back Into the Dark (Part I)

My friend Karl grumbles that there's really no good reason for the year to begin January, but really, it seems to me utterly self-evident why we begin and end our years in darkness, just as it strikes me as equally obvious why we choose that time to celebrate the birth of the Savior. This is, really, rudimentary symbolism, the kind that's hardwired into our brains: The time of year when the shadows are long, and snow covers the ground; the time of year when nothing grows, and the air's so frigid it burns your skin. The time of year when you light candles and wait for the land and sun to be born again, and all the fervent hope that we, too, have a resurrection ahead of us. That there is a spring beyond the winter of the body.

I'm teasing poor Karl a bit, of course, but he makes my point so well. We get so literal-minded sometimes that we fail to grasp the symbols and metaphors we first carved to make sense of the world. The ones we're still soaking in, centuries later. The ones that make up the very syntax of how we relate to nature, to each other, and to the hypothetical God. And of course there's someone reading this right now, some sensible aetheist, who's muttering to himself that we don't need these symbols anymore. They're just relics of the past. We understand how the world works now. And maybe he has a point, but then, I'm no atheist, and I have trouble believing that we understand how the world works when I live in a New England city that's consistently surprised each winter when it snows. Make no mistake, the mind is an amazing thing, and the light of reason has banished many demons. But we're not entirely reasonable creatures, are we? No, there's always some small part of us huddling against the dark in some desolate cave. Perhaps, the, it's easy to see why why our culture is awash in depictions of sex and violence, why we're captivated by them, and the two inevitabilities they promise us: birth and death.

We're born in the dark and, eventually, we head back into it. This is the simple, salient fact of our existence, and not a one of us can do anything but guess as to what, if anything, happens on either side of that short equation. I'm not inviting a theological debate, mind, I'm just pointing to the simplest truth of why we are the way we are: We are, always, surrounded by darkness, and the entirety of human civilization is nothing but a sort of Christmas -- a brief flicker of light amid the dark and cold, and no matter how much we instill ourselves with faith and reason, we know with every thump of our caveman heart that, eventually, we'll each of us, at the end, face that darkness alone.

So we create symbols to deal with all of that, to communicate on that level, to speak to that place that only understands emotional aggregates. And sometimes we call those symbols heroes and monsters, and we let them war inside our skulls to remind us of the darkness, and how we overcome it, over and over, perpetually striving for the distant promise of spring. And sometimes we let our heroes also be monsters, because that, too, is an old and necessary thing. Sometimes what we need from our heroes changes, and so we rewrite our stories accordingly. But it's worth remembering what they sometimes were, because those old stories are always rumbling beneath the new ones. Greek myths are filled with "heroes" who commit atrocities, who lie and murder. Sometimes, they're barely better than the monsters they stand against. Of course, sometimes a little better is better enough, especially when the young of your city are bing fed to the Minotaur. Who cares about Theseus' ill treatment of Ariadne, or his being so self-involved that he forgot to change the color of his sails?

No, they're not exactly the qualities we look for in heroes in today's literature. Except we do. Because nobility and justice are only one set of priorities. There are others -- the ones that give us westerns and samurai films, and the nascent heroic images rising out of the American urban ganglands, from John Wayne films to the brilliant anime series Afro Samurai, the place where personal and familial honor hold sway above all else, and were vengeance has actual currency.

January 1, 2011

Happy New Year!

Did want to take a moment, though, to repost this strip by R.K. Milholland, who regularly does the wonderful webcomic, Something*Positive, because it sums up everything I've been saying about the Muslim Batman nonsense out there (and indeed, mirrors my feelings about the uproar over black English actor Idris Elba playing the Norse god Heimdall in the forthcoming Thor movie.):

Here's to a great 2011, preferably one with fewer instances of racist stupidity permeating the culture. A boy can dream.

December 31, 2010

New Year's Eve

Yesterday, my love letter to local music was published in the Telegram. Just a little reflection on some of my favorite songs that I've encountered. If I had thought about it for another few minutes, I probably would have included Speaker for the Dead's "Saint Peter" or Niki Luparelli's "Toxique," but that's the way it goes. There's always something left undone, or unsaid. The column was never meant to be comprehensive. Just a little thank you to a life that, amid many wild ups and downs, allows me to spend a bit of my time writing about music. That allows me to write about joy.

Joy's an odd commodity, particularly in the pages of a daily newspaper. In the news business, you spend rather a lot of time talking to people about their struggles and tragedies. To be allowed to use some of that space to talk to people about music they love is a blessing beyond words, because it's those small, seemingly trivial joys that make all the rest of the heartache worthwhile. It's an honor to be allowed to do it, and I'm looking forward to doing it for a good while longer.

Never mind that there's a cynical part of my brain that can't help but feel that the years are getting costlier as they go on. Starting with my friend Gabrielle Bouliane's passing in January, on the heels of a good many other significant deaths, followed by the loss of close friends Erica Erdman and Steve Skitz, and friends and favorite sparring partners Ron Offen and Jeff Barnard. (And frankly, I'm even surprising myself in how much I find myself missing those latter two. it doesn't feel like there's anybody of their caliber and character worth crossing swords with out there right now, and certainly no one who's as much fun to do so with.)

And of course, this was the year I shut down The November 3rd Club , a decision I've second-guessed myself on every single day since I made it, and yet I can't really say I've regretted. No, it was the right thing to do. It's a good thing to know when things are finished, even if it hurts like hell in the process. I'm a sentimental old git, and that, too, gets worse every day, but sometimes you just have to know when to let go. Holding on to the past too tightly usually only serves to cause you to neglect the present. And yeah, it's been a costly old year, but there's still this bright and shining future glittering on the edge of vision.

Nov3rd's gone, but sometime very soon I'll be making a few announcements about the next thing, and I'm very excited. And I spend my days writing poems and stories, and writing about music and poetry. How bad can that be? I'm blessed with an amazing wife, and many wonderful friends and family. It's not a bad life. Not in the least.

So here's to absent friends, and to 2011. Frankly, I feel it's insufficient to wish it to be merely good. Let it be brilliant and joyful, and even a little mad. Here's to 2011 being a year worth having had.

December 29, 2010

Please Welcome Our Guest Blogger, Joseph Campbell!

Take it away, Joseph!

All of which is far indeed from the contemporary view; for the democratic ideal of the self-determining individual, the invention of the power-driven machine, and the development of the scientific method of research, have so transformed human life that the long-inherited, timeless universe of symbols has collapsed. In the fateful, epoch-announcing words of Nietzsche's Zarathustra:"Dead are all the gods." One knows the tale; it has been told a thousand ways. It is the hero-cycle of the modern age, the wonderstory of mankind's coming to maturity. The spell of the past, the bondage of tradition, was shattered with sure and mighty strokes. The dream-web of myth fell away; the mind opened to full waking consciousness; and modern man emerged from ancient ignorance, like a butterfly from its cocoon, or like the sun at dawn from the womb of mother night.

It is not only that there is no hiding place for the gods from the searching telescope and microscope; there is no such society any more as the gods once supported. The social unit is not a carrier of religious content, but an economic-political organization. Its ideals are not those of the hieratic pantomime, making visible on earth the forms of heaven, but of the secular state, in hard and unremitting competition for material supremacy and resources. Isolated societies, dream-bounded within a mythologically charged horizon, no longer exist except as areas to be exploited. And within the progressive societies themselves, every last vestige of the ancient human heritage of ritual, morality, and art is in full decay.

The problem of mankind today, therefore, is precisely the opposite to that of men in the comparatively stable periods of those great coordinating mythologies which now are known as lies. Then all meaning was in the group, in the great anonymous forms, none in the self-expressive individual; today no meaning is in the group-none in the world: all is in the individual. But there the meaning is absolutely unconscious. One does not know toward what one moves.One does not know by what one is propelled. The lines of communication between the conscious and the unconscious zones of the human psyche have all been cut, and we have been split in two.

The hero-deed to be wrought is not today what it was in the century of Galileo. Where then there was darkness, now there is light; but also, where light was, there now is darkness. The modern hero-deed must be that of questing to bring to light again the lost Atlantis of the co-ordinated soul.

Obviously, this work cannot be wrought by turning back, or away, from what has been accomplished by the modern revolution; for the problem is nothing if not that of rendering the modern world spiritually significant-or rather (phrasing the same principle the other way round) nothing if not that of making it possible for men and women to come to full human maturity through the conditions of contemporary life. Indeed, these conditions themselves are what have rendered the ancient formulae ineffective, misleading, and even pernicious. The community today is the planet, not the bounded nation; hence the patterns of projected aggression which formerly served to coordinate the ingroup now can only break it into factions. The national idea, with the flag as totem, is today an aggrandizer of the nursery ego, not the annihilator of an infantile situation. ...

... But there is one thing we may know, namely, that as the new symbols become visible, they will not be identical in the various parts of the globe; the circumstances of local life, race, and tradition must all be compounded in the effective forms. Therefore, it is necessary for men to understand, and be able to see, that through various symbols the same redemption is revealed. "Truth is one," we read in the Vedas; "the sages call it by many names." A single song is being inflected through all the colorations of the human choir. General propaganda for one or another of the local solutions, therefore, is superfluous-or much rather, a menace. The way to become human is to learn to recognize the lineaments of God in all of the wonderful modulations of the face of man.

With this we come to the final hint of what the specific orientation of the modern hero-task must be, and discover the real cause for the disintegration of all of our inherited religious formulae. The center of gravity, that is to say, of the realm of mystery and danger has definitely shifted. ... Both the plant and the animal worlds, however, were in the end brought under social control. Whereupon the great field of instructive wonder shifted-to the skies-and mankind enacted the great pantomime of the sacred moon-king, the sacred sun-king, the hieratic, planetary state, and the symbolic festivals of the world-regulating spheres.

Today all of these mysteries have lost their force; their symbols no longer interest our psyche. The notion of a cosmic law, which all existence serves and to which man himself must bend, has long since passed through the preliminary mystical stages represented in the old astrology, and is now simply accepted in mechanical terms as a matter of course. The descent of the Occidental sciences from the heavens to the earth (from seventeenth-century astronomy to nineteenth-century biology), and their concentration today, at last, on man himself (in twentieth-century anthropology and psychology), mark the path of a prodigious transfer of the focal point of human wonder. Not the animal world, not the plant world, not the miracle of the spheres, but man himself is now the crucial mystery. Man is that alien presence with whom the forces of egoism must come to terms, through whom the ego is to be crucified and resurrected, and in whose image society is to be reformed. Man, understood however not as "I" but as "Thou": for the ideals and temporal institutions of no tribe, race, continent, social class, or century, can be the measure of the inexhaustible and multifariously wonderful divine existence that is the life in all of us.

The modern hero, the modern individual who dares to heed the call and seek the mansion of that presence with whom it is our whole destiny to be atoned, cannot, indeed must not, wait for his community to cast off its slough of pride, fear, rationalized avarice, and sanctified misunderstanding. "Live," Nietzsche says, "Live as though the day were here." It is not society that is to guide and save the creative hero, but precisely the reverse. And so every one of us shares the supreme ordeal-carries the cross of the redeemer -not in the bright moments of his tribe's great victories, but in the silences of his personal despair.

And that's where we'll be picking up from, when we return to the subject, as we examine both what constitutes a hero, and what that means in the context of the 21st Century.

And we'll probably be talking a bit about Afro Samurai. For real.

December 27, 2010

Everyone's a Critic

Writes Saltz, in the latter article, "I failed at practicing criticism on TV. I wasn’t nearly clear or articulate enough about why I liked and disliked things. I didn’t explain how artists embed thought into material. There’s no doubt in my mind that many other critics would have done better than I did. But I’d gladly try again. I learned a lot from the experience. For decades, nearly every successful artist has come out of art school. I’m not saying forget about school and enter the art world via a reality-TV show. But Work of Art reminded me that there are many ways to become an artist and many communities to be an artist in. The show also changed the way I think about my job. Over the ten weeks it aired, hundreds of strangers stopped me on the street to talk about it. In the middle of nowhere, I’d be having passionate discussions about art with laypeople. It happened in the hundreds, then thousands of comments that appeared below the recaps I wrote for nymag.com. Many of these came from people who said they’d never written about art before. Most were as articulate as any critic. I responded frequently, admitted when I was wrong, and asked others to expand on ideas. By the show’s end, over a quarter-million words had been generated. In my last recap I wrote, 'An accidental art criticism sprang up … Together we were crumbs and butter of a mysterious madeleine. The delivery mechanism had turned itself inside out.' Instead of one voice speaking to the many, there were many voices speaking to me—and one another. Coherently. I now understand that, like us, criticism contains multitudes."

It's hard, coming from a poetry slam background, to not have a visceral sense of empathy for that sentiment. If slam has given the poetry world one great gift, one standard worth standing behind, it's been the democratization of art, the steadfast belief that everyone is entitled to an opinion about the work of art in front of them. It may be ill-informed and, on occasion, drunken, but if a work of art makes you feel nothing, it makes you feel nothing. If it makes you feel something, even if it's what I would deem sentimental claptrap, then it makes you feel something. There's an inherent value in that, and if it's not the be-all and end-all of a piece of art's merit, it's still worthy of consideration. Am I still more interested in reading what, say, Robert Bohm, Susan Somers-Willett, Jordan Davis or Peter Campion have to say about poetry than some guy at the bar? Well, yes. But that's because I'm interested in reading that discussion at a more advanced level, not because the guy at the bar's opinion doesn't matter. (And to be fair, I've more than once taken advice about particular poems from feedback given by random guys at bars.) No, I find, when we get into discussions about criticism, be it poetry criticism or any other artistic genre, I get annoyed by the presupposition that it all needs to be any open thing.

Panero, in an assault on Saltz that seems to comprise equal parts honest concern for the art from, reactionary venom and no small degree of jealousy, writes, "The material intimacy of direct artistic experience—seeing paint, sensing the artist’s hand—does not emerge from social networking. Rather, great art offers a necessary alternative to an over-mediated culture. Art writers should use the internet to counteract the dematerialization of a hyper-connected world, not encourage it through false promises. Criticism is in crisis, but new-media gambits like reality television and social networking, and the illusory communities they generate, are not the answers in themselves. The point of good art criticism, whether you read it in print or online, should be to turn off the computer, shut off the television, and enjoy art in the flesh."

Well ... yes and no. Certainly, I can see Panero's point of view, but there are a couple of statements in this one paragraph that I'm afraid I have to take issue with:

1.) The material intimacy of direct artistic experience—seeing paint, sensing the artist’s hand—does not emerge from social networking.

Fair point, but one does hope that the majority of people commenting on Saltz' articles are, indeed, going out and experiencing the work for themselves, or at least work in their geographic vicinity. What's been lacking in the past has been accessibility to art -- a problem that cuts straight across the arts, from top to bottom. People who may have had some interest in visual art didn't read articles about it, because it was all discussion of something that was far away -- inevitably in New York City, although occasionally London or Paris -- where the publishers and critics lived. The overall effect was alienating, and built walls between artwork and potential audiences. But I do agree that the work should be best experienced first-hand. It's just that social media now makes it a lot easier to figure out where to look, and offers competing views, which challenge art-world establishments.

2.) Rather, great art offers a necessary alternative to an over-mediated culture. Art writers should use the internet to counteract the dematerialization of a hyper-connected world, not encourage it through false promises.

I don't recall this ever being in the job description. Was there a memo? Was it caught in my SPAM filter? All glibness aside, this strikes me as a personal issue, and not a call-to-arms. Art should, to a great degree, reflect the world where it exists. Now, creating work (and criticism) that challenges "dematerialization of a hyper-connected world" is a worthy goal, but I'd hesitate to state it should be the only goal. As with anything in life, the immense connectivity of the day is a mixed bag, with blessings and pitfalls. Some people see immense value, and indeed, use art to navigate the emerging landscape. To deny the nature of the modern would altogether strikes me as reactionary to a troubling degree.

Panero writes that "the job of a contemporary critic remains to seek out that vitality, tell us where to find it, and explore its strengths," and in this, we're in total accord. But it strikes me that rejecting tools outright, even tools that have some downsides, is not a sensible tactic, and indeed, blinds both the artist and the critic to possibilities and new voices. It's foolish to pretend the world hasn't changed, and indeed, not recognizing that salient fact puts the critic already at a disadvantage.

ETA: It occurs to me that, what's bothering me most in the Panero article, is the blanket assertions that television and social media have no role in art or criticism. Writing about navigating the roles they could play, and watching experiments -- even flawed ones -- unfold to be far more interesting. The impulse to remain cloistered has never done any of the arts much good.

December 23, 2010

Now Leaving the 20th Century

These blog posts have all been an examination of a single metaphor, manifesting itself in myriad forms: the hero. "The Hero With a Thousand Faces," as Joseph Campbell said (and kudos to whomever won the betting pool as to how long it would take for me to bring him into this mess.) But not just any hero. No, I've been trying to come to grips with how the hero manifests now, whether he or she is named Buffy Summers, Harry Potter, Olivia Dunham, Hiro Nakamura, Veronica Mars, Jack Bauer, Deborah Morgan, Jaimie Reyes, Kim Possible, Jack Harkness, Kate Kane, Virgil Hawkins, Renee Montoya, Aang, Stephanie Brown, Malcolm Reynolds, Martha Jones or Ryan Choi. And I think, amid all of this, something's become clear to me: We're still struggling to enter the 21st Century.

You'd think something like that would be as easy as turning a calendar, wouldn't you? But it isn't. The past and the future are siege engines firing back and forth at the present, to steal a line from someone or other (Warren Ellis, maybe?), and we stand somewhere in the fallout. Everything around us changes, and we find ourselves facing questions that seem almost ridiculous, questioning assumptions about race, misogyny, homophobia, war, violence, economics, health care, even the distribution of information. Even the fairness of the platform we move that information around on. It's almost mind-boggling, and I think I can have a modicum of sympathy for people overwhelmed by it all, this idea that some of our basic assumptions of the world need to not only be re-evaluated, but built entirely from the bottom up. I listen to some of the Tea Party fever rage, and I keep hearing the same phrase, over and over again. "I want my country back."

Here's the sharpest, kindest answer: You can't have it. No one ever gets the past back, no matter how badly you think you want it. And really, you probably don't want it anywhere near as much as you think you do. History, for all its hardships, generally does move in the right direction. As a whole, we do become collectively more free, healthier, less violent and more comfortable as we move forward, but it sucks a lot along the way. It, really, really does. Every 80 years or so, American history pretty much takes a nose dive, and spends 10 to 20 years or so rebuilding. We're probably in the middle of that right now, and to tell you the truth, I have no idea what the other side is going to look like. History says it'll probably be a bit better, all around. History lies a lot, to steal another line, and there are still places in this country (never mind the rest of the world) where it still won't look that great. History's a zigzagging line, but the progression, over all, is usually upward.

But the past doesn't go away, either. Sometimes that's a good thing. The Bill of Rights becomes the syntax of our political vocabulary, sometimes holding it up like scripture, sometimes stewing when it gets in the way of what we think we want or need. Sometimes, we struggle over interpretations of what it means, or what it means today. Because we do live in a different world than it was in 1776. That's OK. Women can vote, we don't own slaves and non-property owners can vote. Never mind inoculations against a good many infectious diseases. The world's a better place than it was, and for all our struggles with it sometimes, over free speech and the right to bear arms, and just about any other issue we can conjure, it's still one of the things that makes us better than what we might have otherwise been. And we keep Superman around, too, as dusty and oddly quaint as he often seems. Because it's still, in the end, a good ideal. One worth remembering.

Still, some relics from the past can change. From the end of slavery to women's suffrage, from the Civil Rights Movement to the repeal of DADT, we do get better. We tinker and rebuild things for the future all the time. Stephen Moffat offers a Sherlock Holmes in the 21st Century, detached from others, choosing mostly to communicate via technology, and it works. Grant Morrison gives us a Batman who, rather than fighting a solitary war against crime in one city, turns costumed crime fighting into a franchise (like 7-11, or Al-Qaeda), with decentralized Batman operatives around the world, including a French one who is an Algerian Muslim immigrant, with requisite racist backlash from people who've not actually read the story, but who instead simply balk at any positive portrayal of a Muslim. As if such a large group of people -- about a sixth of the planet -- were all one thing. As if none of them are capable of being heroes. As if Muslim police and firefighters in New York weren't heroes on 9-11, some sacrificing their lives to save others. (But then, we don't always treat those real-life heroes all that well, do we?) Some of it is worth holding onto. It's not perfect, but it can be refitted.

But a lot of it? A lot of it can go. I raised the question earlier of no African-American poets being included in Anis Shivani's roundup of major poets discussing the influences of major poets. To his credit, Shivani responded, and said it wasn't for lack of trying. But that seems beside the point, because as much better as things have gotten, the shadow of history still falls on our literature as much as it does any other aspect of our culture. Writes critic Jordan Davis, "Literary history, at least as far as race in America is concerned, is stuck, and the doctrine of separate but equal has to be overturned again and again, with every book published. If the doctrine were dead, then it would be common knowledge that Robert Hayden is at least as remarkable a poet as Robert Lowell, or that the Hugheses—Ted and Langston—run about even; or that it would be ignorant of a young poet to study Elizabeth Bishop to the exclusion of Rita Dove, or vice versa. It would also finally be possible to assess the claim that Amiri Baraka's work—his early work as LeRoi Jones, anyway—outdoes them all. ... It can be difficult to be a young black poet now. You're courted by publishers and anthologists, by the halls of academe; yet post-colonial and subaltern and diaspora scholars, who fight turf battles over what to call themselves, tell you what to write and how to write it, questioning your language and your motives (or, worse, applauding them) before you've written a line. Easier, I suspect, to be a young poet everyone is ignoring. Easier for what? To do what? Write a memorable poem that makes everyone around take notice? Then where are all the show-stopping thousands of young ignored poets? Is their game good enough to stand up to some of the best trash talk of our times, talk so dismissive it doesn't even bother with the second person?" (Thanks to Daniel Nester for the reference.)

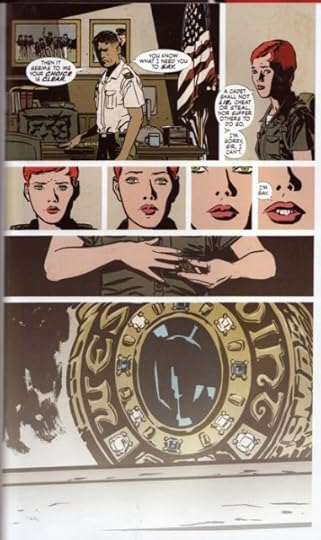

It's overwhelming, and the smart money's on fighting the exhausting series of small battles, one after the other, because they're the ones that actually add up, over time, to effective change. You can't simply elect a Barack Obama and walk away. He's a change, but not the totality of it. The changes that need to be made burble up from the culture, eventually flowing into some sort of tide. Literature -- fiction, poetry, cinema, theater, comic books -- are where that plays out, and what wins in that arena is what smacks of truth, not which suits an ideology. You can pass a billion bills in Congress, and I'm forced to wonder how much of it adds up to a single comic book page of a teenage girl -- the newest Batgirl, Stephanie Brown -- slapping Batman.

Writes the author of that comic, Bryan Q. Miller, "Stephanie’s journey over the course of the volume leading up to this issue was all about self-awareness. And about validation. She had finally started to get some traction regarding being okay with who SHE is/was. And then this legend, this symbol, shows back up. This man she probably thought she’d never have to deal with again. A man who’s approval she’d never truly been able to procure. But then, as soon as she saw his face, as soon as she realized Bruce was up to his old tricks again, that they were dancing to a very familiar tune, Batgirl realized something - not only did she not want Bruce’s approval… she didn’t NEED it. And that he would dare to presume to tell her what she did and did not need AND-THEN-SHE-TEA-KETTLED-AND-SLAPPED-HIM!"

It's magic. Sometimes the past -- even the past worth keeping around, in some form -- needs to get slapped, to be reminded that for all the good it's done, no matter how much we may love it, it doesn't own this moment. Because when the culture is dictated by nostalgia and habit, it's the present that gets neglected.

December 22, 2010

Odds and Ends ...

*I've made much hay, throughout this mess, of the TV show Fringe, and particularly, the character Olivia Dunham. I love Olivia -- she's smart, professional, and while she has odd, unflashy powers (she can travel between alternate universes, and see things that are from other universes) she's not really a superhero. She has what is sometimes described as a photographic memory, and a full life and story which involves family and romance. But ultimately she's all about her work. My kind of character. Alas, the people at Fox have seen to move the adequately rated Fringe to Friday nights, which has been a tomb for many fine shows, notably Firefly and Dollhouse, further proving one TV insider's assertion to me that Fox has the best development team in television, and marketers who have no idea what to do with them. I09 offers some things you can do to keep the show on the air.

*Way back in the article that got me rolling on this, Charlie Anders pondered examples of heroism -- not just in female characters, but in recent pop culture in general, and came up pretty empty. It's hard to argue when DC Women Kick Ass re-examines the death of Supergirl in Crisis on Infinite Earths, back in the '80s, which will always be among the gold standards of "heroic deaths" in comic books. They also offer some good thoughts on the rumored forthcoming death of Latino superhero Blue Beetle, none of them too kind toward old DC Comics, and rightly so. In related news, Bleeding Cool has some reactions from comic book creators on the repeal of DADT. The one from Larry Hama is touching. The one from Chuck Dixon is, to use DCWKA's terminology, "homophobic bullshit." AS DCWKA points out, it's significant, because he's been accused of homophobia in his writing before. (Go read their blog post. It's worth it.) What's clear here is that editorial at comic companies really do have the ability to put their feet down and keep themselves from being tarred as racists or homophobes, but somehow they seem to either be oblivious to what's happening in their own pages, or to how it's going to be perceived. Neither of which strikes me as a sensible attitude in an editor. (And as that's the job description on my nonexistent business cards, I know something of what I speak.) Surely, there's some sort of middle ground between creative freedom and change?

*Adam Christopher from Escape Pod talks up superheroes as the next big thing in fiction, using many of the same examples I did earlier, save one: Jeff DeRego's Union Dues stories ... which appear on Escape Pod! C'mon, dude. There's a time and a place for modesty!

December 20, 2010

Diversity, Heroes and Literature ...

In my excitement about DADT (and, admittedly, disappointment about the DREAM act), I've been echoing some of what the DC Women Kicking Ass blogs have been posting, regarding Kate Kane, AKA Batwoman. But they've run a lot of good stuff about female comic book characters there, and it's very worth reading. I found their overviews on Stephanie Brown (Batgirl) and Lois Lane to be particularly relevant in connecting those characters to the culture. Writings like these and Andrew Wheeler's wonderful "No More Mutants" colum for Bleeding Cool do a great job of keeping diversity issues forward in the minds of the creators and fans of pop culture fictions, the groups most likely to be able to influence the continued diversity of the characters.

It almost feels odd explaining why this might be important. They are, after all, simply stories, and in the case of comic books, not particularly widely-read ones, at that. It seems odd to have to explain why a Kate Kane or (to switch to TV) a Capt. Jack Harkness might be extremely relevant to a gay teenager, how being able to see themselves as an action hero is the sort of thing that might actually change the course of someone's life. Moreover, it's almost unbelievable that one needs to point out that seeing diversity reflected in mediums such as film, television and comics goes a long way toward helping the culture sort out and normalize its own issues with a swiftly changing population mix, never mind the strictly commecial concerns that changing landcape presents for media companies looking 10 or 20 years down the road.

No, it would seem self-evident, but it terribly much isn't. The culture gets stuck in tokenism, reverting to type with a shift in the breeze. Take the odd case of the superhero, the Atom. In the midst of a number of relaunches and redesigns, comics writer Grant Morrison (who is,, for my money, the absolute best in the business at reconceiving old superhero concepts, even if reactionary, usually corporate, forces usually undo his best ideas) came up with a new Atom, Ryan Choi, a young Chinese scientist and longtime fan of the preceeding Atom, Ray Palmer. In the hands of writer Gail Simone, his comic was a delicious read. When it changed hands, it disintegrated, and eventually was canceled. Soon after, DC Comics, wanting to return Palmer to the role, killed off the character in a different book. It was brutal and unneccesary, especially when you've got three different white guys running around as the flash. It was hardly DC's only instance of reluctance to part with its Caucasian characters, but it was certainly the most egregious, especially considering just how good the Simone run was. The fact remains, DC poked at diversifying its characters, but then bolted the moment it was hard. Could they have bolstered him by, say putting him in the Justice League, as they did with the Latino Super hero, Jamie Reyes (The Blue Beetle), whom they put in Teen Titans. Whatever their reasons for doing so, the move was distasteful and reeked of, if not overt racism, then at least a sort of enormous insensitivity.

This is the sort of bias that echoes throughout a culture, its significance snowballing as it moves further from the original slight. Nor is it restricted to "low" culture mediums. Take, for example, Huffington Post poetry critic Anis Shivani, who recently asked 22 poets to name who they believe is the most important contemporary poet and what influence that poet has had on his or her work. In what seems to be the sort of oversight that only the least race-conscious are capable of making -- that is to say, those who believe they are "blind to race," rather than keeping a conscious check on themselves and their own culturally inherited biases -- the list of poets queried seems to be devoid entirely of African-American writers. It's diverse, certainly -- there are Latino writers, and at least one Arab writer -- but unless I'm mis-identifying a writer's background, none of them are black. Moreover, although I do not recognize every poet that was named as influential in the article and so couldn't say for certain, but it appears that the only black poet named as being "influential" to contemporary poetry was Aimé Césaire. Forgive me if I'm wrong about that. I didn't recognize every name listed. But I recognized most, and it became clear fairly quickly that most of the poets interviewed selected those whose work and background was, quite understandably, most like their own.

But because of the initial act of bias (intentional or otherwise), an entire generation of highly influential black American poets was excluded from the list. Nikki Giovanni? Lucille Clifton? Sekou Sundiata? Quincy Troupe? These are poets that almost everyone who works the "live" (slam, coffeehouse, whatever) side of poetry has a direct debt to, not just African-American poets, but by positioning the focus of the lens where he did, Shivani manages to exclude the work of black American poets entirely. And that's a problem, especially when you have a forum and a readership. It's not just irresponsible, it creates an incomplete and misleading picture, one that echoes out and has ramifications beyond the initial mistake.

December 19, 2010

Digression: DADT and Batwoman (Part II)

I've been talking about heroes and fiction a lot lately, and there are a lot of ways that can be relevant to a culture, but perhaps the single greatest role a fictional hero can play is to illustrate the emotional truths behind ideas that can be too easily intellectualized, allowing injustices to be rationalized away. It's not the only role they can play, certainly, but it's one Rucka hit out of the park with this story: crafting a believable gay character who could be both related to and idolized, one who overcomes tragedy and still finds it in herself to help others.

Now, the argument will always be that it can be just as easily written the other way, and on a technical level, your correct. All sorts of hateful garbage gets published. Bit there's a spark when the writing hits something true. It's a matter of craft. Injustices against any groups are born out of caricature, and lack of empathy, and portrayals that re-enforce those views usually betray the lack of empathy with a hollowness of characterization. You can have conservative writers and characters -- science fiction, particularly, is rife with them -- but even those conservatives, the ones who write well, are slow to abandon empathy. Empathy is a tool in any artists' hands, and transcends political beliefs. With it, you can use a political issue as a starting point to create art. Without it, you're simply creating propaganda.

Morning Thoughts

In the meantime, I offer Shaun Sutner's excellent story on Worcester bloggers.