Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 86

February 10, 2011

Nine lives, by William Dalrymple: book review

Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India by William Dalrymple

Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India by William Dalrymple

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Until I was seven years old I lived in Westvile, near Durban, where Hindu temples were a familiar feature of the landscape, so I have always been curious about Hindu beliefs and practices, and have, at various times, tried to read something about it. I discovered, however, that most books about Hinduism published in the West were abstract and philosopical, and none of them explained those temples that dotted the landscape, or what people did in them. At school I learnt in History classes a little about Indian religion, with things like the life of the Buddha, and the Muslim conquests, but it was very sketchy. The most informative book I read was a work of fiction, Rudyard Kipling's Kim, which gave a more human picture.

Gateway to Hindu temple at Mount Edgecombe, Natal

On a trip to Singapore in 1985 I had a stop-over of a few days in Thailand, and visited some Buddhist temples. I discovered from tourist booklets that it was considered rude to point one's feet at a Buddha statue, but there was still little to say what the temple meant to Buddhists, or what they did there.

So when I saw this book, I thought it could give a more human picture of Indian religion, and I was not disappointed. I had previously read William Dalrymple's From the Holy Mountain, and, as an Orthodox Christian I thought he managed to give a fair picture of Orthodox Christianity, so I hoped that he would give an equally fair picture of Indian religion, and that his biographical approach would give a reasonably accurate portrayal of what these religions mean to those who practise them.

"Religion" is itself a Western concept, shaped by the encounter between the Enlightenment and Christianity in the West, and so imposing it on India (or other countries outside Western Europe and its cultural offshoots) is bound to produce a distorted impression. "Hinduism" is a Western perception of Indian religion, viewing it through the spectacles of Western modernity. Western authors (and Indian authors writing for Western readers) find it difficult to avoid this trap. Dalrymple manages to avoid it by his biographical approach, letting his subjects tell their own stories.

The stories that they tell also shows some of the variety of Indian culture and society. Dalrymple explores the byways rather than the highways, the backwaters rather than the mainstream Vaishnavite and Shivite cults. And this probably gives a better picture too, since for the majority of Indians, religion is local, and the central worship is of local gods and godesses.

The book begins with the story of a Jain nun, whose best friend had starved herself to death. One of the qualities that Jain nuns and monks try to cultivate is non-attachment, so the nun describes her feelings of loss of her friend, and the conflict of this with the ideal of non-attachment.

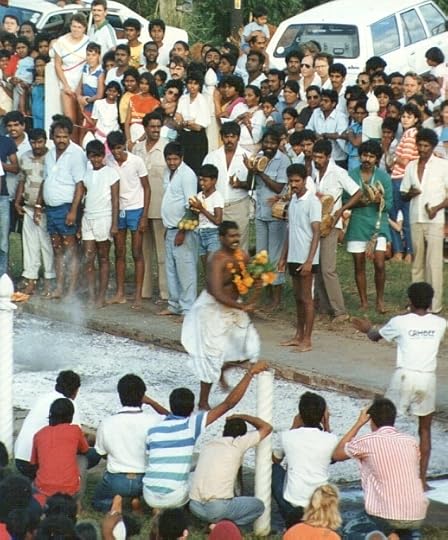

Ceremony at Umbilo Temple, Durban, 1987

Next is the dancer of Kannur. There is a troupe of dancers who travel around villages portraying the stories and activities of the gods, and in the course of the performance they are possessed by the spirit of the god, and become the god, so that the dance is as much an act of worship as a dramatic performance.

The third is one of the daughters of Yellama, one of the sacred prostitutes in the service of the goddess.

Then comes the singer of epics. Like the dancers, the singers tell the stories of the gods in song, in front of the phad, a kind of scroll with illustrations of what the songs are about, which is also a form of portable temple. The songs are learnt and passed on by oral tradition, and Dalrymple makes some interesting points about the differences between oral and written cultures, and the effects of modern technology on the tradition — will people bother to learn the songs when you can get them all on DVD? He also notes how this has been lost in the West, where epics like Homer's Iliad have long been passed on in written form, and the oral performance has been completely lost.

In the story of the Red Fairy, Dalrymple moves across the border to Pakistan, and speaks to one of the followers of sufi Islam. A woman who was born in Bihar, on the eastern side of India, to a Muslim family, and fled to East Pakistan when Hindu-Muslim hostility grew too great, and had to flee again when East Pakistan broke away to become Bangladesh. Now the mystical sufis are under threat from the Wahhabis. This reform movement in Islam, often called "fundamentalist" by Western journalists, though "puritan" or "protestant" might be better analogies with Christian history, aims to purify Islam of accretions like the sufi cult of the saints, which the Wahhabis regard as syncretistic superstitions. Wahhabi is the official form of Islam in Saudi-Arabia, and is being spread throughout the Islamic world with Saudi oil money. The people at the shrine of the sufi saint complain that the Arab madrasa students come to make trouble, and blow up the shrines. Dalrymple explains that madrasa students are known as Talibs, from which the word Taliban is derived.

And this takes me back to my schooldays. When I was 14, a group from our school went on a camp in the Western Cape, at Firgrove near Somerset West. It was an evangelical Christian camp, with Bible studies every day, and much singing of evangelistic choruses. One day we went on a walk to Macassar Beach, the site of Sheik Yussuf's tomb or kramat. But in those days our Evangelical Christian teachers were not Islamophobic, and they explained that Sheik Yussuf was one of the first Islamic teachers in the Cape, and was revered as a saint, and we went in to sit quietly and reverently in the kramat, where the tomb itself was covered with layer upon layer of silk cloths. These Evangelical teachers, whom some would call "fundamentalists", taught us to respect people of other religions, and to respect their holy places, even if we did not share all their beliefs. But no such respect is shown by the Wahhabis, who blow up such shrines in Pakistan. And the West also had its Taliban, led by the likes of Oliver Cromwell, who behaved in a similar fashion.

Dalrymple manages to explain all this, as far as I can recall, without once using the word "fundamentalist". He lets his people tell their own stories.

Then comes the monk's tale, the story of a Buddhist monk from Tibet, who left his monastery and monastic vows to become a guerrilla fighter against the Chinese in the Tibetan resistance, and later in the Indian army. When he retired from the army he returned to his monastic lifeat Dharamsala in India, where the Dalai Lama lives, in a settlement of Tibetan refugees.

The seventh is the story of the maker of idols, who casts bronze statues of gods for the temples, a trade that has been handed down from father to son for generations, but the idol maker's own son does not want to follow in his father's footsteps, and is more interested in becoming a computer engineer.

There is the Lady Twilight, the goddess of a crematorium, whose devotees live in the grounds of the crematorium, and use skulls from the cremated remains for their devotions. Grim and macabre as it sounds, Dalrymple find that they believe that central to it all is love.

Fire walking at Umbilo Temple, Durban, 1987

Through the dwellers in the crematorium he comes into contact with the Bauls, wandering minstrels. It goes back to the singer of epics in an earlier chapter, because the Bauls wander from place to place, singing songs, but many of them are agnostic, almost atheist, and they reject the conventional religion of temple and mosque, they reject the caste system, and the conventions of society. They are holy madmen, holy fools. Though Dalrymple does not say so, they could be compared to the hippies of the West.

Nine lives, of people living in different places and having different religious beliefs and practices, yet dedicated to a way of life based on their religion. Some ascetics, some prostitutes, and some somewhere in between. By telling their stories, Dalrymple makes it possible to catch brief glimpses of Indian "religion", without imposing too much of a Western framework on it.

February 8, 2011

Creativity and worship

In 1967 I was studying at St Chad's College in Durham, England, and I went to spend the Christmas vacation with an Augustinian community at Breda in the Netherlands.

It was only a couple of years after the Second Vatican Council, and liturgical reform was in the air, and the Dutch Catholics were the avant garde of the Roman Catholic Church, doing things that had not been done before.

While I was staying with them they asked me to translate papers and articles from Dutch into English, and their papers were mostly about liturgical reforms. One of the papers stressed the point that the new forms of liturgy were more flexible, and therefore would demand a great deal more creativity from the celebrant. Apart from the use of the vernacular instead of Latin, this was the biggest change.

With the old Roman Catholic liturgy, no creativity was needed. All one had to do was learn what to say, when to say it, and what actions to perform. There was a greater or lesser degree of ceremonial. High Mass was done with lots of ministers, servers, choirs and clouds of incense. Low Mass could be gabbled by a priest on his own in 20 minutes.

Now the services could be tailored to the needs of each community. It was recognised that different societies and different cultures had different needs and expectations. So creativity was demanded, but was not always to hand. The result was not always happy.

Priests who had been saying the Latin Mass for 20 years were suddenly lost, and if they lacked the spark of creativity, the congregations suffered. When it was in Latin, which few people understood, at least it sounded mysterous and numinous. When it was in a rather banal vernacular translation, with an uncreative priest, it could be deadly dull.

If you've read this far, and haven't guessed it by now, for this synchroblog I'll be discussing one aspect of creativity, the creativity in leading worship referred to in the paper by the Dutch Augustinian. I'll also be discussing it mainly as a personal narrative of my own experience, so if that sounds too boring, scroll down to the end and pick one of the other posts.

I returned to St Chad's College after the vac, where they had their own tangles with liturgical reform. The previous term they has been using the C hurch of England's "Series II" services in the college chapel, which had been sabotaged by some members of staff, who didn't like it. On my return, the college staff had unilaterally reverted to the old version, which was a kind of Anglo-Catholic version of the Roman Latin Mass, only in English. Some of the other students had been at a conference that had been addressed by Walter Hollenweger, a Swiss-Chilean Pentecostal who worked for the World Council of Churches. He got them all fired up on liturgical creativity, and had said that the people who knew about creative liturgy were journalists. So there was a group of us who were feeling somewhat rebellious about the reversion to the old ways in the college chapel.

In the Easter vac in 1968, two of us went to Switzerland for a course on Orthodox theology for non-Orthodox theological students, and took the opportunity to go and see Walter Hollenweger at his office in the WCC headquarters in Geneva, to discuss our complaints. I won't go into all the details here, but we had a minor revolution in the college. In July 1968 I returned to South Africa with ideas of liturgical creativity and also having had a first taste of Orthodox liturgy. I attended a couple of "experimental" services organised by the University Christian Movement at Rhodes University, but wasn't very impressed.

In 1969 I found myself at the Missions to Seamen in Durban, where the main form of public worship was a kind of truncated Anglican Evensong, with a few sentimental frills for those who had romantic notions of the sea and sailors. When I was asked by the priest in Greenwood Park to lead a couple of services when he was on leave, and he told me that they had the bishop's permission to scrap Evensong and do "experimental" worship, it sounded like an opportunity to be creative. I asked him if I could call in the youth group of the Christian Institute, an ecumenical group, to help plan and lead it. He agreed. The result of it was that I was fired by the Anglican bishop of Natal. You can read the full story at Notes from underground: Psychedelic Christian Worship — thecages, which is really an integral part of this post.

The next few years saw the rise of the charismatic renewal movement in the Anglican Church (and several other denominations). This led to a new desire for praise and worship among those who were touched by the renewal, but the emphasis was not on creativity, but spontaneity.

At the same time the Anglican Church introduced new forms of service, called Liturgy 1975. This was minimalist. They were liturgical outlines rather than liturgical texts, and so they made room for both creativity and sponteneity. Because the printed service books services trimmed everything regarded as non-essential, they were regarded as the "bare bones". The local congregation provided the flesh and skin, and, it was hoped, the Holy Spirit would breathe life into it. This sometimes happened, if there was the right mix of creativity and spontaneity.

The service for the Holy Eucharist had a section headed "Praise", which began as follows:

Praise the Lord

Praise him you servants of the Lord

You that stand in the house of the Lord

Praise the name of the Lord

Then is said the following, which may be omitted in Lent

Glory to God in the highest

and peace to his people on earth…

In parishes influenced by the charismatic renewal, the space between "Praise the name of the Lord" and "Glory to God in the highest" could be filled with anything from a few minutes to several hours of spontaneous prayer and praise. This could be either serial or parallel. Sometimes people prayed one at a time, in plain language or in tongues, someone might start a hymn or chorus, which would be taken up by others, and sometimes there would be singing or praying in tongues, with everyone praying at once. In places like Zululand it got quite exuberant, with people shouting and jumping up and down. When the celebrant, or the minister leading that part of the service judged that it was enough, it would go on to "Glory to God in the highest", which, if sung well, could sum up the praise part of the service, or if said (uncreatively) could bring everyone down to earth with a bump.

Ten years later, in 1985, we began going to Orthodox services, and in 1987 we joined the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox liturgical texts were maximalist rather than minimalist. There was lots of repetition, which was one of the things the Anglican and Roman Catholic liturgical reformers had been determined to do away with. "Again and again in peace let us pray to the Lord" was exactly right, but "Let us complete our prayer to the Lord" usually indicated that there was another hour or two to go. There was little room for creativity or spontaneity. And the texts were theologically concentrated. There was sometimes an enormous amount of theology packed into a few words. There is a lot of repetition, but after 25 years of the repetition, it still isn't exhausted. There is always something new, something that has been there all along, but which suddenly impinges on one's consciousness.

So looking back over more than forty years on the remarks of the Dutch Augustinians about the need for more creativity in leading worship with the (then) new liturgical revisions, I've come to question whether it was a good thing.

I think of our "psychedelic" service in St Columba's, Greenwood Park. It took a great deal of preparation, and a great deal of creative thinking. As a once-off, it wasn't too bad, but the thought of repeating that amount of effort once or twice or even more every week for ten, twenty, thirty years or more is daunting. Sooner or later the creative juices must run out, and too much depends on a small group of leaders.

The Orthodox liturgies don't run out of juice because they don't rely on the creative mood of the moment, which can be minimal if one is feeling tired, or sick, or depressed. The Orthodox services rely on 1000 or more years of experience, which is inexhaustible, whereas the creative effort of a small group of people soon becomes exhausted. The problem is that not everyone can be creative all the time, and some people are not creative at all, and so what was once inspiring and creative and spontaneous worship can soon descend into banality and boredom.

After becoming Orthodox, we were out of the western charismatic scene for a while, but a couple of years ago I had a taste of it at the Amahoro Conference, where I mistook what was intended to be "worship" for the band practising (see What is worship? | Khanya).

I'm sure that creativity has its place in the Christian life, but in leading worship I think it is greatly overrated.

___

This post is part of a synchroblog on Christianity and creativity, in which several people post on the same theme on the same day. Here are some of the other posts on the topic:

Bethany Stedman – How God Creates

EmmaNadine – Creativity and Christianity

Bill Sahlman – Created, Continued Creativity

Heidi Renee – Synchroblog Creativity and Christianity

Annie Bullock – Old Things are New

John O'Keefe – What is Half of 11

Kathy Escobar – open.

Tim Nichols – Artist-Priests in God's Poetic World

Maurice Broaddus – The Artist and the Church

Jeremy Meyers – Creativity First Christian Act (link not working yet)

Steve Dehner – The Divine Projectionist (link not working yet)

Ellen Haroutunian – Creativity and Christianity: It Matters

Tammy Carter – His Instrument His Song

February 7, 2011

Hell became afraid

On Sunday I posted a kind of digest of my sermon at St Nicholas, because someone had asked me to do so. It was on the phrase "casting away the ancestral curse", which occurs in the Resurrectional Troparion for Tone 4. This prompted someone else to write:

Thank you so much i did not know that you would give the sermons out the one I wanted was 2 weeks ago when you said that *HELL IS A PERSON NOT A PLACE* , that was mind blowing , would you be able to send that one to me as I needs to get my head around it .

It is not so much that hell is not a place but a person, but rather that Hell is something of both, and is rather a person in charge of a place.

At this point I should perhaps explain that in the Orthodox Church every Sunday is a little Pascha (Easter), a commemoration of the resurrection of Christ, and each Sunday has a couple of theme-hymns for this, a Troparion and a Kontakion (sometimes called Apolyiticon). These follow the eight tones of the Octoechos, a set of hymns with proper melodies that are repeated every eight weeks.

These hymns contain a lot of the theology of the church, and so two weeks before I discussed the Troparion and Kontakion for Tone 2:

TROPARION

When Thou didst descend to death, O Life Immortal,

Thou didst slay hell with the splendour of Thy Godhead!

And when from the depths Thou didst raise the dead,

all the powers of heaven cried out:

O Giver of Life! Christ our God! Glory to Thee!

KONTAKION

Hell became afraid, O Almighty Saviour,

seeing the miracle of Thy Resurrection from the tomb!

The dead arose!

Creation, with Adam, beheld this and rejoiced with Thee!

And the world, O my Saviour, praises Thee forever.

I discussed the phrase "hell became afraid" and "Thou didst slay hell", and pointed out that though we often think of hell as a place, in the language of these hymns hell is referred to as much as a person as a place.

The English word Hell is linked to a number of Greek and Hebrew words: Hades, Tartarus, Sheol, and also (among the Romans) Pluto and Dis.

I can't remember exactly what I said in my sermon two weeks ago, but the gist of it can be found in an earlier post on this blog on Go to Hell!

February 6, 2011

Casting away the ancestral curse

This post is based on a sermon I preached this morning, the Sunday of Zacchaeus, at the Church of St Nicholas of Japan in Brixton, Johannesburg. Some members of the congregation asked me to post a written version of it, so I've tried to write it down here.

Six or seven times a year we sing the Resurrectional Troparion of the Fourth Tone:

When the women disciples of the Lord

learned from the angel the joyous message of Thy Resurrection;

They cast away the ancestral curse

and elatedly told the apostles:

Death is overthrown!

Christ God is risen,

granting the world great mercy.

In the Orthodox Church we sing our theology, and several times during the service the deacon says "Let us attend", and that means standing to attention like a soldier awaiting orders. If we pay attention to what we sing, we can learn a lot about the theology of the church, and that Troparion is a summary of the Gospel, the Good News about Jesus Christ. You would have noticed, if you were paying attention, that the hymn is based on the gospel reading at Matins, which describes the Myrrhbearing Women coming to the tomb of Jesus, and then running to tell the apostles, who dismissed it as an idle tale, but Peter went to check up on it, found the tomb empty, and didn't know what to make of it.

There is one line in the hymn that doesn't appear in the gospel story, however, though it is added to show the extraordinary and world-changing nature of this event. "They cast away the ancestral curse".

What is the ancestral curse, and how and why did they cast it away?

The ancestral curse is sometimes called ancestral sin, and sometimes original sin.

This is a rather tricky subject, because there are different understandings of original sin, and especially between the Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches. At the risk of oversimplifying it, I will use an analogy. In the last couple of centuries social scientists (sociologists, psychologists etc) have sometimes argued about whether heredity or environment play the most important part in making us what we are. Are we what we are because of our genes, our DNA, or because of our environment and upbringing — whether our parents are rich or poor, go to good schools, bad schools or none at all? Some have made studies of identical twins (who share the same DNA) who have been brought up separately, to try to find answers to the question.

It could be said, very roughly, that Roman Catholic theology leans to the hereditary explanation, while Orthodox theology leans to the environmental explanation of original sin. This can be seen in the Roman Catholic doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, which holds that God intervened to miraculously remove the stain (macula) of original sin from the Virgin Mary at the moment of her conception. To the Orthodox, this looks like an exercise in genetic modification. And to the Orthodox it looks quite unnecessary. The problem with the Roman Catholic doctrine of the Immaculate Conception from an Orthodox point of view is not with the immaculate conception of the Theotokos, but with the idea of the maculate conception of the rest of us. Orthodox theologians question the notion of a stain of sin that is passed on genetically from generation to generation, and needed to be miraculously removed in one particular case.

Orthodox theology tends to lean more to the "environmental" explanation. Original sin, the ancestral curse, is caused by our being born in a world that has gone away from God, and fallen into the hands of the Evil One (I John 5:19). Jesus spoke of the devil as "the ruler of this world". We are born in a world that lies in the power of the devil. If we are born in the Republic of South Africa, we are automatically South African citizens. So, when we are born in this world we are born as citizens of the Kingdom of Satan. We are literally born possessed by the devil. In society in which slave owning was lawful (as it was in the Cape Colony in the 18th century) a child born to slaves becomes the property, the slave, of the slave owner. One of my wife's ancestors was the daughter of a slave woman and a free man, and her father manumitted her — the legal documents are in the Cape archives. He bought her freedom, and the technical word for that is redemption, which is also a theological word that describes what Christ has done for us, redeeming us from slavery to sin, death and the devil. So we are born possessed by Satan, which is why the Orthodox baptism service begins with not one, but four exorcisms.

Different approaches to baptism can also show the different understandings or original sin. In the Roman Catholic Church, until recently, it was regarded as important to baptise babies lest, having been born in sin, they should die in sin. There was a special place for unbaptised babies who died, called "limbo", though I believe that that is no longer taught. But it is certainly the idea of original sin that was stressed in the Roman Catholic understanding of the importance of infant baptism.

Some Protestant Christians in the West developed a different undertanding of baptism. Instead of seeing it as God's act, they saw it as a purely human act. We were baptised as an act of obedience, because Jesus commanded it, and as a witness to our faith. This differs from the Roman Catholic understanding, but there is the same undercurrent of legalism that is found in the Roman Catholic understanding, of the necessity of obeying something seen as a command of God. They therefore believe that young children should not be baptised, because they are "too young to understand it".

The Orthodox understanding of the need for infant baptism is somewhat different. It's usually not expressed directly in contrast to the Western views, because it was always accepted. But it comes out when we sing our theology, and especially on Holy Saturday, when we sing about the people of Israel fleeing from slavery in Egypt and crossing the Red Sea. This is seen as a type of baptism, and a type of our salvation. The people of Israel, escaping from slavery in Egypt, and pursued by Pharaoh's army, come to the barrier of the Red Sea. They can go forward and drown, or stay where they are and be taken back into slavery. Then God suddenly opens a way of escape through the sea. Did they carry their infant children across with them, or did they leave them on the Egyptian shore because "they were too young to understand it"? You can bet they didn't leave their kids behind to the tender mercies of Pharaoh's army.

In the Orthodox Church the baptism service in some ways resembles a secular naturalisation ceremony. After the exorcisms we face the West and renounce our citizenship of the kingdom of Satan, and then we turn to the East and accept Christ as our king and our God. One American translation of the baptismal liturgy even borrows the wording of a secular naturalisation ceremony, and the candidates say "I pledge allegiance to Christ". And so we are transferred, as St Paul puts it, "from the authority of darkness to the kingdom of God's beloved Son" (Colossians 1:13), not by the transmutation of our DNA, as the Western doctrine of original sin implies, but by a change of orientation.

This is also seen in the gospel reading at the Divine Liturgy, because today is the Sunday of Zacchaeus, and that points us to Pascha, and the preparation for Pascha, Great Lent, which is now approaching. One of the things that Great Lent reminds us of is how far we have strayed from God. We may, by baptism, have become citizens of Christ's kingdom, but all too often we don't behave like it. And the story of Zaccheus shows us that there is no sin that is so great that it cannot be forgiven. People muttered about Jesus going to dinner with Zacchaeus because he was such a bad man. And the change in Zaccheus begins because he wanted to see Jesus. That is where it begins. As we approach Great Lent and Pascha, we must want to see Jesus, and then salvation will come to our house, as it did to the house of Zacchaeus.

We also see a change in Zacchaeus. He promises to put right the wrong he had done, and in doing so, he too casts away the ancestral curse.

So what is the ancestral curse? We can read it in Genesis chapter 3, but one of the significant parts of it is this:

Gen 3:17 And unto Adam he said, Because thou hast hearkened unto the voice of thy wife, and hast eaten of the tree, of which I commanded thee, saying, Thou shalt not eat of it: cursed is the ground for thy sake; in toil shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life;

The ancestral curse is not merely that we are cursed, but that we become a curse. The very ground is cursed because of us. As we were travelling to church there was a programme on the radio that talked about the problem of acid water in abandoned mines, that is killing the fish in the rivers and causing the vegetation alongside the rivers to die. Man's sin affects not ourselves alone, but we become a curse to the whole creation.

But what happened when Zaccheus cast away the ancestral curse? It meant that instead of being a curse, he became a blessing. He gave away half his goods to the poor, and thus he became a blessing to the poor instead of being a curse to them.

And that is one of the consequences of switching allegiance from the kingdom of Satan to the Kingdom of God. We cast away the ancestral curse, and instead of being a curse, we become a blessing.

January 29, 2011

Tales from Dystopia VIII: Deportation from Namibia

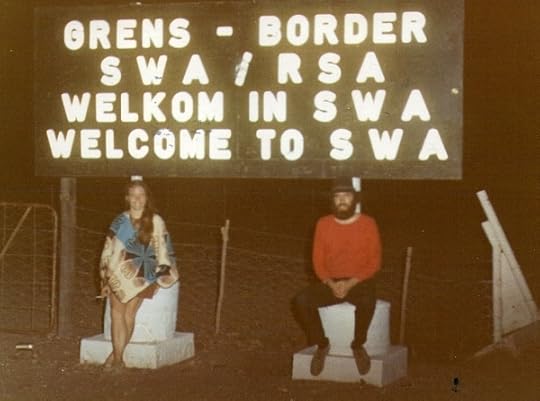

In 1972 I was deported from Namibia, along with the Anglican bishop of Damaraland Colin Winter, the diocesan secretary Dave de Beer, and Toni Halberstadt. We were given until midnight on 4th March 1972 to leave the territory. A couple of lawyers urged us to contest the deportation order in the courts, and said they would act free of charge if we did so, so we hung around until the Supreme Court verdict was announced at about 2:30 pm. It went against us, so we left Windhoek and headed for the border, which we crossed at about 10 minutes before the midnight deadline. We stopped at the border for a commemorative photo, which I recently put on Facebook.

Antoinette Halberstadt and Stephen Hayes leaving Namibia 10 minutes before deportation deadline

The photos sparked off some discussion among Toni's Facebook friends who asked what had happened, but there isn't really room to tell it in Facebook comments, so I thought I'd say a bit more about it in a blog post, though this isn't by any means the full story.

I worked as a proof reader and rewrite man for the Windhoek Advertiser, then the only English-language daily newspaper in Namibia, which the South African government called South West Africa, and continued to rule, though the World Court had declared, in the middle of 1971, that South Africa had no legal right to govern the country. Dave de Beer and I were also stringers for the Argus Group of South African newspapers, and sent them stories for which we got paid a modest fee. Toni Halberstadt was a teacher at the Anglican Church school of St Mary's, Odibo, which was on the Angolan border, and about 500 miles from Windhoek. She was kicked out of there by the South African government, and also came to work for the Windhoek Advertiser.

One day the chief reporter of the Windhoek Advertiser, that legendary journalist J.M. (Jakkals Mal) Smith came into the newsroom and announced that a strike was being planned in Walvis Bay. The rest of us laughed it off. There were seven fish factories in Walvis Bay and the workers there were always going on strike, and there were strikes three or four times a year. No, said Smittie, this is a big one.

And so it turned out to be.

The strike started because Dave de Beer, speaking at Wits University, had said that the contract labour system for Ovambo workers in Namibia was a form of slavery (see Tales from Dystopia I: Epukululo Lovawambo | Khanya). This was picked up by a journalist who happened to be in the room quite by accident, and was splashed all over the front page of Die Suidwester (the National Party newspaper in Namibia) for a week, one of their quarterly bouts of Anglican-bashing.

This prompted the Commissioner General for Ovamboland, Jannie de Wet, to say, in a broadcast on Radio Ovambo, that the contract labour system was not slavery, because the workers were free to go home at any time they wanted. Some of the workers in Walvis Bay, who heard the broadcast, wrote letters to the Ovambo compounds in other towns in Namibia, suggesting that on a certain day they should all go home, "just as the Boer Jannie de Wet had said."

On a Sunday afternoon in Windhoek a meeting was held in the veld just outside the compound and the letter was read out, and they decided that they would not go to work on the Monday. So on Monday 13 December 1971 none of the Ovambo workers in Windhoek left the compound. And just to make sure they didn't, the compound was surrounded by police.

Government officials, the government-supporting press and white businessmen, who were all convinced that blacks were incapable of organising a booze-up in a brewery, attributed the total stayaway from work to "outside agitators" (the stock phrase used in such situations). Because those who made such statements were invariably racists convinced that blacks were too stupid to organise a strike, they either said or implied that these "outside agitators" were white. The South African newspapers for which we were stringers sent their own reporters to cover the big story, but they didn't have any local contacts and repeated the government line. We had contacts and continued to report the story from the strikers' point of view, as described above. We weren't aware, at that point, that the "white agitators" who were enforcing the strike were the South African Police, who were allowing no one to enter or leave the Ovambo compound.

Our informants were three contract workers who nipped out of the compound on the Sunday evening before the strike started. They worked for Noki Construction, a building firm set up by the Anglican Church to train people in the building trade. They said that they had left, not because they disagreed with the aims of the strike, but because they weren't dissatisfied with their contracts, and also, because if the police went into the compound and found they were Anglicans, they would be blamed for starting the strike and would be arrested.

On 21 December Toni Halberstadt and I were called in by the owner (not the editor) of the Windhoek Advertiser, a guy called Juergen Meinert, and fired with immediate effect. No notice, we were to leave at once. I'd never met Meinert before, and wouldn't have known what he looked like. We had been hired by the editor, but the owner stepped in to fire us, I suspect through pressure from the Security Police, or perhaps from the editor of the sister paper, the Allgemeine Zeitung. He was Kurt Dahlmann, a former Luftwaffe pilot in World War II.

Soon after that we went on holiday to South Africa. Toni went to the Northern Cape, while I went on a tour visiting friends and family in South Africa, and taking Marge Schmidt, Bishop Winter's secretary, and her two daughters, to see the sights.

When we returned to Windhoek, some "ringleaders" of the strike had been arrested and faced trial. Dave de Beer and I were now reporting for the SA Morning Group of newspapers, and, having been fired from the Windhoek Advertiser, that was now my sole source of income, so I attended the trial every day. The defence of the strikers was organised by the Anglican Church, and there was an observer from the International Commission of Jurists, a Judge Booth from New York. The "ringleaders" were charged, among other things, with intimidating the strikers to cause them to stay away from work.

The evidence that came out at the trial showed that what we had written in our reports was substantially accurate, though there were several things that we had not known. The policeman in charge of the police who surrounded the compound was cross-examined by the defence advocate, and asked if they let anyone in and out of the compound. And the police officer said that they let them out if they had permission from their own people inside. "So the police were carrying out the orders of the strike leaders?" asked the defence advocate. And the Magistrate had a broad grin on his face.

On another occasion he was asked about the stikers boycotting the compound food. They went in a group to local shops to buy food – about 1200 of them in all. The defence advocate asked how, if those people were desperate to go to work but for the intimidation, it was possible to prevent them from going to work. The police witness insisted that they were intimidated. Asked how many were intimidating them, he said about six. Were they armed? Yes, with sticks. How many had sticks? Two of them. The defence advocate said "We are told in the Bible that Samson slew 600 Philistines with the jawbone of an ass, so are you telling us that these two men with sticks were stronger than Samson?" Again the magistrate grinned at the discomfiture of the police witness.

When we were reporting the story, we interviewed Katutura shopkeepers about conditions inside the compounds, because the strikers had patronised their shops, and were chatting about it as they did so. Among the shopkeepers were Clemens Kapuuo, the Herero chief (unrecognised by the government) who was later killed by an unknown assassin, and David Meroro, the local Swapo leader. None of the staff reporters from the South African newspapers thought to interview them, even thought they were not only in touch with the stikers, but were political leaders in their own right. Views of black people, no matter how well-informed, just did not count among the white-controlled media in those days.

And a couple of weeks after the trial ended, we were deported.

The (all-white, all National Party) South West Africa legislative assembly had a special all-night sitting to amend the law so that we could be deported without appeal to the courts (the law was originally intended to apply to suspected German spies between the world wars, when South Africa governed the former German colony of South West Africa under a League of Nations Mandate). Nevertheless, these clever lawyers persuaded us to contest the deportation order, promising that they would do it free of charge. The case was dismissed with costs. Bishop Colin Winter raised the costs among well-wishers overseas, but we did not realise that the sneaky lawyers had pocketed the money and not paid it over to the SAW Administration, and one day the Durban sheriff came to seize my goods for the unpaid debt, which I knew nothing about. But that too is another story.

January 23, 2011

What is African? Race and identity

Yesterday's City Press had a bunch of articles on being African, sparked off by an earlier article We are not all Africans: only black people are: City Press: Columnists:

Henry Ford once said: "You can have any colour, as long as it is black." Similarly, native inhabitants of Africa say: "You can be an African in any colour, as long as you are black."There has been a sudden demand for an African to come in a variety of colours.

During the days of slavery, when an African was a commodity, there was never a demand for him in any colour but black.

There is now an attempt in the 21st century to redefine the colour scheme of an African.

Now whites want to be classified as African too.

Others take a different view, like White people are African too!: News24: Columnists: Khaya Dlanga:

Human beings are referred to as Earthlings because they live on the planet Earth. A person of any colour born in South Africa, for example, is called a South African. No one denies their South Africanness simply because of the colour of their skin. South Africa is on the African continent, and therefore a South African is an African regardless of colour. Unfortunately it is as simple as that. No great revelation here.

This country has been divided for too long. Those divisions didn't work. To attempt to divide us again, even under the guise of creating debate, isn't doing us any favours.

The truth is this debate is worn out and pointless because it doesn't achieve anything but division.

This has led to quite a discussion in the blogosphere, for example here Becoming African | my contemplations.

Sentletse Diakanyo's contention that only black people can be African takes me back to the political debates of the 1950s and 1960s.

Back in the 1950s, in South Africa, white people were called, in English, "Europeans", and so in the apartheid labelling of the time various entrances were labelled "Europeans only" or "Non-Europeans only". Someone, I forget who, pointed out how silly it was by introducing himself, "I'm a non-European, from non-Euirope." The English-language newspapers of the time referred to black people as "natives", but this came to be thought derogatory and so some time around 1960s they switched to "African". The government didn't go for this, because if translated into Afrikaans, "African" would become "Afrikaner" and that clearly would not do, so the government adopted "Bantu" as a substitute for "native". The government Department of Native Affairs became the Department of Bantu Affairs.

The confusion was apparent in an Afrikaans reader I had at school when I was about 10 years old. We had to take it in turns to read and I lost my place and the teacher kept yelling at me "die naturel" (the native). I couldn't find it on the page because my book had "die kaffer", and some of the newer editions had "die Bantoe". So we learnt how political correctness was always moving the goalposts, although neither "political correctness" nor "moving the goal posts" were part of current idiom back then.

In opposition circles the African National Congress (ANC) only had black members, but it was part of the Congress Alliance, where the Congress of Democrats had white members and there were Indian and Coloured Congresses too. The ANC comprised a great variety of people with different views. Some were left and communist, some were cenbtrist and liberal, wanting to establish a non-racial democracy. Some were African nationalist, and sometimes referred to themselves as Africanist. They objected to the influence of white communists on the ANC, and broke away in the late 1950s to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). Their aim was to liberate Africa from white rule, and for them "African" had both colour and geographgical connotations. One of their aims, inherited from the Pan African movement of the 1920s, was to create a United States of Africa. Many in the PAC rejected the Congress Alliance kind of thinking, and said that whites, coloureds and Indians had no role to play in the liberation of South Africa; it was only for Africans.

This attitude of the PAC led some to accuse them of racism, which lead some in the movement to adjust their definition of "African". It did not mean only black people, they said. It could include white, coloured and Indian people as well, provided that they identified themselves as African, and did not regard themselves as having a "home" on another continent, like Europe or Asia.

So the term "African" could mean various different things. It could refer to people of a particular skin colour and ethnic origin. It could refer to those whose political thinking was continent-wide, rather than confined to one country. And it could mean those who, no matter what their colour, identified themselves as African. And things haven't changed much from 50 years ago.

One thing that apartheid fostered was racial stereotypes, and the belief that cultures should not mix but that they should "develop separately along their own lines". Their "own lines" were usually laid down by the National Party government.

In 1961 and 62 I was a bus conductor in the Johannesburg Transport Department, which had buses for "Europeans" "Non-Europeans" and "Asiatics and Coloureds". The "European" buses weren't labelled, but the others were, and while Asiatics and Coloureds could ride on the Non-European buses, Africans/Natives/Bantu/Blacks could not ride on the Asiatic and Coloured buses. When I was training as a bus conductor most of my fellow trainees were urbanising Afrikaners straight from the farm, and we were told that we must not call the black clients "kaffers". The transport department staff referred to them as "Kadals" or "Kadallies" — I assume that that was a reference to Clements Kadalie, a prominent black trade unionist of the 1930s.

And from observing and interacting with passengers in these separate universes, I developed my own racial stereotypes. Whites were grumpy when sober and mildly uncooperative when drunk. Blacks were cheerful and chatty when sober and sullen and uncooperative when drunk. Indians were cold, aloof and icily polite and always sober. Coloureds (who travelled on the same buses as the Indians) were rarely sober but rude and uncooperative whether drunk or sober. These are gross generalisations, and there were, of course, exceptions. By "uncooperative" I mean that they did not pay their fares promptly. And of course the way people behaved when they were bus passengers did not determine the way they behaved in the rest of their lives. The white passengers also varied more depending on the bus routes. Those on the Dunkeld route were upper middle class, living in posh mansions with lots of servants. Those on the South Hills route were working class living in council houses. Blacks travelling to Dunkeld were usually servants to the white madams on the white buses. Blacks travelling on the Race Course route on weekdays were usually workers in factories in Booysens, Selby and Ophirton, while on Saturdays they were usually going to bet on the horses. It did give an observation point to see how the other half lived.

So though I became a strong proponent of a non-racial society, and joined the Liberal Party, which advocated a non-racial democratic society, I never imagined that people of all cultures and ethnic groups were the same. But despite the obvious differences, I thought that all should have equal legal rights in society. and that if they were to develop along their own lines, they should be free to decide for themselves what those lines were and whether those lines cut across the boundaries of the various ethnic groups that apartheid insisted must be kept separate.

When I went to university I met students of different backgrounds, especially at student conferences, such as those of the Anglican Students Federation, because the universities themselves were segregated and becoming more so. One whom I met at such conferences was Stephen Gawe. He was also a member of the interndenominational Student Christian Association, which itself was being forced to become segregated under pressure from its Afrikaans section. In 1964 he was detained and eventually charged with being a member of the banned ANC, and sentenced to a year in jail. On being released he was banned. I was active in the Liberal Party, especially during my final year at university, and warned that I would be banned, and left for the UK just before getting a banning order.

I thought I'd feel at home in the UK. After all, they spoke English there, and so it should be easy to communicate. Most of the books I'd read when growing up, both fiction and non-fiction, had been published in the UK. The last thing I expected was culture shock, and because it was so unexpected, it probably hit me harder. I knew the names of London streets and landmarks from reading about them, and from playing Monopoly, though they turned out to be utterly different from what I had pictured when reading about them.

A few months later I was joined by by Stephen Gawe, who had a bursary to study at Oxford as I had at Durham. We compared notes, and found we had suffered almost exactly the same culture shock. For our first few months in Britain we both felt alien and alienated. And i then realised that in spite of apartheid, which had tried to separate us and say we were too different to associate with each other, we had in common that we were African and not European. We had grown up under the same sky. We had grown up under the same oppressive government, and struggled against it. Africa was my home. And when Stephen Gawe got married, I was both flattered and honoured when he asked me to be his best man.

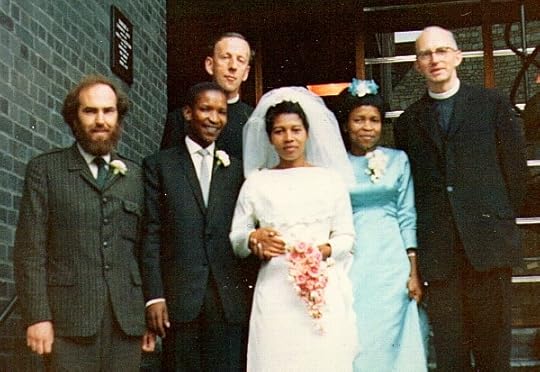

Wedding of Stephen Gawe and Tozie Mzamo, Oxford 1967

As a student in Britain I made some British friends. But they could never share with me what Stephen Gawe shared with me. I could see and share to some extent the environment in which they grey up, but they never knew where I was coming from. To them i was, and would remain, a "wog". I'd been to a wog college, had a wog degree, and wore a wog academic hood on formal occasions when we had to wear such things. As an alien I had to register with the police, and notify them of any change of address. When I went to Durham to the university, they told me at the police station that there was another South African student who had registered. He was in a different college, but we met. We was black and I was white, and though I had never met him before, there was a bond; we were homeboys.

And then I think, there are lots of black people in Britain, British born, and their parents born in Britain too. Are they British, or will they forever be regarded as aliens, as second-class citizens. There are some, like English nationalists, who would say that black people in Britain may be British, but they are not and can never be English. It seems to work both ways.

People spoke about differences between European and African culturee, or between black and white culture. Some of these have been described as characteristically African. But I've discovered that most of them are not. What is described as "African" is actually premodern, and those characteristics were common in Europe before the premodern area. Europe has exported modernity to Africa, and it is something picked up through Western education and urbanisation.

As time has passed, I've become less aware of questions of identity. I've stopped bothering so much about whether I am African or whatever. Perhaps that is a result of encountering more different cultures, and discovering more points of contact between different cultures. I read Samuel Huntington's book The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order and realised that I am a walking clash of civilizations myself. I'm African by birth, Western by education, and Orthodox by religion. I've got a foot in three camps, and so don't have a clearcut "identity". But that has ceased to bother me.

So when Sentletse Diakanyo complains "Now whites want to be classified as African too" all I can say is that I'd rather not be classified at all. Classification into such groups was one of the features of apartheid, and it's high time we stopped being obsessed by racial identity and wanting to be classified.

And when it comes to identity, the one thing I reject, utterly and completely, is any sense of concept of "white" identity. Perhaps that's a hangover of my rejection of apartheid, but one thing I really hate is when people speak of "the white community". There is no such thing, and even if there were, would want no part in it. And there is no such thing as "white" culture or "white" values. And I'm not sure that one can speak of European culture or African culture either. How much common culture is there between Albania and France, or between Tunisia and Swaziland?

Fifteen years ago I spent a couple of weeks in the Orthodox seminary in Nairobi, doing research for my doctoral thesis. There were students from all over Africa. I found it interesting that the students from West Africa seemed to gravitate to me. They were suffering from culture shoch, and they couldn't stand the East African food, and perhaps they thought that I, as a foreigner, would be equally alienated. But actually I felt quite at home in Kenyan culture. It seemed to have a lot of similarities with southern Africa, and far fewer with West Africa. One thing I did find stange about Kenyan culture, though, was their attitude to South Africa. When people heard I was from South Africa I expected them to ask about our (then fairly recent) transition to democracy. But no, the only thing they were interested in was the Mandela divorce and who would get the money.

One of the things that helped me to discover my primary identity, however, was the republican referendum of 1960. The referendum question was "Are you in favour of a republic for the union?" Were you a republican or a monarchist. I decided that I was a monarchist. My primary loyalty was to the kingdom of God, and the republic of South Africa came a very poor second, especially when the main criterion for citizenship was whiteness.

January 21, 2011

What is a priest?

I've recently noticed on the Anglican blogs I read more frequent references to "lay presidency" and "diaconal presidency" at the Eucharist. Such ideas strike me as completely daft, and remind me of why I quit the Anglican Church 25 years ago.

So why, if I'm no longer Anglican, do I blog about such things? It certainly doesn't bother me, because it no longer affects me, and it makes little difference to my life what Anglicans ultimately decide about such things. I've been debating with myself whether to write a blog post on it or not. It's not that I hope to influence Anglicans to do one thing rather than another. I suppose at one level my interest is academic. My academic field of study is missiology, and so I am interested in the way that ministry in the church affects mission and vice versa. Also, I cannot deny that my experience as an Anglican, and especially in training self-supporting priests and deacons in the Anglican Diocese of Zululand, helped to shape my understanding of ministry in the church, and thus helped, if indirectly, to lead me to Orthodoxy. And I also believe that whereas the Orthodox understanding of ministry in the church is theologically sound, the practical application of it has often been a hindrance to mission. So I think it could be quite useful to "think aloud" about it in my blog.

So, to go back to the beginning, why do I think "lay presidency" and "diaconal presidency" are daft?

They are daft because they seem to assume the interchangeability of ministries in the church. Think of a different field — a Formula I racing team. It's a pretty good example of what St Paul is talking about when he compares the church to a body, with each of the parts of the body having a different function. Most of what you see on TV is one member of the team, the driver. The driver gets pole position or some other position. The winning drivers appear on the podium at the end of the race and squirt each other with champagne. But occasionally during the race, during the pit stops, you catch glimpses of other members of the team — the guy who handles the refuelling, the guys who change the wheels, the guys who jack the car up so the others can change the wheels. And even less frequently you catch glimpses of other people behind the scenes. There's the team manager, people who monitor the car's performance and track conditions on computers, and so on. And then there are the ones you never see — the people who arrange the logistics — that spares are available when needed, and those who arrange to transport the whole kit and caboodle to the next race venue.

But what if the driver ate something that disagreed with him at lunch, and had to make a pit stop to puke? Do they say "Oh, let the guy who jacks the car up drive, and let the guy who changes the left rear wheel handle the jack." Not likely. As St Paul puts it (1 Cor 12:14-18):

For the body is not one member, but many. If the foot shall say, Because I am not the hand, I am not of the body; it is not therefore not of the body. And if the ear shall say, Because I am not the eye, I am not of the body; it is not therefore not of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where were the hearing? If the whole were hearing, where were the smelling?

But now hath God set the members each one of them in the body, even as it pleased him.

St Paul was not talking about a Formula I team, but of the church, and if the analogy applies to a Formula I racing team, how much more does it apply to the church?

In my Anglican days, as Director of Training for Ministry in the Anglican Diocese of Zululand, one of my duties was to attend the annual meeting of the Provincial Department of Theological Education. This gathered diocesan trainers, representatives of the theological seminaries and an episcopal chairman, and they would discuss for 3-4 days at a residential conference. And almost invariably, at the beginning of the meeting, someone would say something like, "Before we can decide about training for the ministry, we have to be clear on what a priest is." And out would come the newsprint and the felt-tipped pens, and someone would write at the top of a sheet, "What is a priest?" and the rest of the meeting would be devoted to brainstorming that, and writing down what was said on the newsprint. At one such meeting I asked "Didn't anyone save the newsprint from last time? Can't we just put that up and move on?" and there were glares and exasperated snorts at such a suggestion of a departure from the established ritual, for such it was.

The question itself was interesting. It was always, "What is a priest?" Never "What is a deacon?" or "What is an evangelist?" or "What is a prophet?" (there is more about deacons at Deacons and diaconate | Khanya). Behind it lay the assumption of a "one-man band" model of ministry. The priest did everything, and of course needed to be trained to do everything. And at some point the representatives of the theological seminaries would get edgy, and one of them would say something like, "There are only 24 hours in the day, and the curriculum is pretty crowded as it is. We can't just keep adding things without taking something away. If we cut the lunch break to 15 minutes and drop New Testament II we might be able to squeeze in Marxism and Bookkeeping, but not all the other things on the list."

Oh, and if any Pentecostals are reading this and you have managed to get this far without being bored out of your skull, don't me smug because you don't have priests, or think you believe in the "priesthood of all believers". Just ask yourself "What is a pastor?" Because a one-man band pastor is really no different from a one-man band priest, and bears as little relation to the New Testament.

Imagine if the Formula I team was just the driver, and there was no pit crew, never mind all the others, the mechanics, the logistics people and all the rest. But when they discussed "What is a priest?" the assumption seemed to be that the priesthood was the ministry.

And all this talk of "lay presidency" and "diaconal presidency" seems to be just the other side of the coin. After loading the priest with all the ministries of the whole team, they now want to take the one ministry that is actually characteristic of a priest and give that to everyone else. It's as if, in the Formula I team, the Driver changes the wheels, watches the computers, makes the tea, and organises the spares, but anyone else does the actual driving. Inverting a distorted idea of ministry doesn't take away the distortions. If a deacon (or anyone else for that matter) can preside at the celebration of the eucharist, why not ordain them as priests? If my bishop told me that he wanted me, as a deacon, to preside at the Eucharist, I'd be seriously annoyed. If I thought God was calling me to preside at the Eucharist, I would seek ordination as a priest. That is what a priest does.

So I really wonder why so many Anglicans seem to want to have so many unordained priests floating around. Why not just ordain them? And if you are going to have lots and lots of unordained priests, why bother to have ordained ones? What are they for?

I suspect that the real reason is clericalism and pride. There are not enough priests to preside at all the eucharists that need people to preside at them, but if you have too many priests, it would lower the prestige of "the" ministry, which depends on its scarcity value. So "lay presidency" is just a manifestation of the old Anglican disease of pluralism, where, in the 18th century, a priest could be Rector of several parishes, and thus be entitled to the tithes and the titles of all of them, but couldn't be in all those place at once on a Sunday, so employed a poorly-paid assistant curate to do the actual work. As Roland Allen once put it, the chief obstacle to "voluntary clergy"is the jealousy of the present clergy for their position.

Something similar happened in some Anglican parishes during the height of the charismatic renewal about 30 years ago. In those parishes they read in the New Testament about "elders", so they appointed "elders", but never bothered to ask the bishop to ordain them. But I don't think they ever expected them to preside at the eucharist either. So there were two "half-ideas" floating around. There was talk in some places of "self-supporting priests" and there was talk in other places of "elders", but nobody seemed to connect the two and see that they were precisely the same thing. If these "elders" had been ordained by the bishop, and also presided at the eucharist, there would have been the self-supporting priests, and Roland Allen's vision might have been fulfilled.

I once spoke about this at a clergy conference in the Anglican diocese of Natal, and was attacked by two priests (of the Evangelical persuasion), who encouraged the appointment of unordained elders in their parishes. They simply did not believe me when I said that the word "priest" means "elder", and that in the church "elders" and "priests" were the same thing. The English word "priest" is a contraction of the Greek presviteros, and in the New Testament the "elders" were presbyters, or priests. John Milton, who favoured the congregational form of church government, and disliked the presbyterian form introduced by Cromwell & Co, knew the difference, and said "New presbyter is but old priest writ large".

Some Evangelicals make much of the doctrine of "the priesthood of all believers" (not a biblical term, by the way) and believe that there should not be an order of ministry called "priests" because all believers are priests. But ask them if they believe in the "eldership of all believers" and why there should therefore not be elders in the church, and they become less certain. The problem is that in English Bibles the Greek word "presviteros" is translated as "elder" rather than as "priest", and the English word "priest" is used to translate another Greek word, "ierefs", and while there is a connection between priest as in presviteros and priest as in ierefs, it is different from what many people seem to imagine.

And in all the discussions about "What is a priest?" that took place is a preliminary to training for "the" ministry, there were two fatal errors or omissions, first, that the priest is primarily an elder, and secondly that the ministry of a priest is not "the" ministry, but one ministry among many.

It used to be the case that in many places Orthodox priests had little specialised academic theological training. Academic theologians were mostly lay people, and in many places still are. But now, especially in the West, the idea seems to be gaining ground among the Orthodox that there is a need for "an educated clergy", and so the same disease that I noticed among the Anglicans seems to be taking root among the Orthodox as well.

What training does a priest need?

Primarily training as a worship leader, and especially presiding at the Divine Liturgy, with all that that implies. The priest is the link between the parish and the wider church — the priest is ordained by the bishop, and cannot celebrate the Divine Liturgy without the Antimension from the bishop. The priest commemorates the bishop in the Liturgy (and, in the Preparation service, the bishop who ordained him). The qualifications of elders in the New Testament are primarily moral rather than academic, though the bishop, especially, should have enough knowledge of doctrine to be able to convict gainsayers (Titus 1:9).

Another interesting thing is that in the New Testament the elders (ie priests) of the church are always plural. St Paul calls to him the elders of Ephesus (Acts 20:17), Titus is urged to appoint elders in every city (Titus 1:5) and when Christians are sick they should call for the priests of the church to anoint them (James 5:14). This is recognised in the Orthodox service of anointing of the sick, which, if done properly, as St Mark taught us when he brought the gospel to Africa in the first century, requires seven priests and seven deacons for its performance.

Academic theology has its place, but not every priest needs to be an academic theologian, and academic theologians do not need to be priests.

And if priests are not the ministry, but one ministry among many, what about the others, and how should they be trained? And, if people are to be trained for those ministries, we also need to ask what they are.

Ralph Winter, the Presbyterian missiolgist who died a couple of years ago, used to refer to two different kinds of ministry in the church, which he called Modality and Sodality. Those fancy names don't tell us very much, but he believed that the Modality ministries were those that belonged to the local church, which was a community of people of all ages, and a great variety of different people. The Sodality was a more selective community; it was itinerant rather than local, and required particular skills, calling, or training. The Modality ministries, those of the local church, included the ministries of bishops, priests and deacons. The Sodality ministries included monks (who needed a monastic calling in addition to their call to be Christians), missionaries, apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastor/teachers and so on.

The Methodist movement, which grew up in the Church of England in the 18th century, was originally an example of a Sodality ministry. Early Methodists were members of the Church of England, so they went for the sacraments to their local Anglican parish church, but the Methodist Society, as a kind of ginger group within the church, had its own local preachers, and also had itinerant pastor/teachers who travelled in a circuit to a group of Methodist Societies to exhort, encourage and teach them. So the ministry of Methodist ministers was quite different from that of Anglican priests. It was, to use Winter's terms, a Sodality ministry rather than a Modality ministry.

But when the Methodists broke from the Anglicans, the Anglicans no longer provided the sacraments, so Methodist ministers gradually came more and more to resemble Anglican priests, and tended to settle down in one place, and the "itinerant" part of it became no more than a nostalgic longing for a vanished past.

Conversely, in places like Zululand, Anglican priests became more like the original Methodist ministers. The priest would settle in a place and built up a mission centre (sometimes called a mission station) with a church, a school, and sometimes a clinic or hospital). Evangelists, paid and unpaid, took the gospel to the surrounding countryside and formed Christian congregations, which were called "outstations". And the priest, like the early Methodist ministers, would itinerate to the outstations, for preaching, teaching and the sacraments. Contrary to St Paul's instructions to Titus, they did not appoint elders (priests) in every place, but rather catechists, who were authorised to preach and teach (which they were often ill-qualified to do) but not to administer the sacraments (which they could probably have been taught to do quite easily). One catechist preached every Sunday on the working of the steam engine, which he had read about in a book.

An Anglican evangelist in Sekhukhuniland had an itinerant ministry preaching the gospel, and within a short time had planted about 30 new congregations, after which it stopped growing. Why? Because he was ordained a priest (the only one) and had a complex itinerary for visiting those congregations for the Eucharist, and so he had no time to go to new places. He had become a Mass nomad. But if, as St Paul instructed Titus, he had appointed elders in every place where he had planted a church, that problem would not have arisen. He, or someone else, could have visited them like the original Methodist ministers, as itinerant pastor/teachers, to encourage and teach them, though with a less demanding schedule and being able to spend more quality time in each place, without the need to rush off somewhere else for Mass.

Among the early Methodists, people like John Wesley were itinerant evangelists just like the Anglican one in Sekhukhuniland, but they were able to avoid the problems in Sekhukhuniland, at least for a while, because there was already a network of Anglican parish churches. The Orthodox Church too had its John Wesley. St Cosmas the Aetolian was a contemporary of John Wesley, and had a similar itinerant evangelistic ministry in the Balkans. Under Ottoman Turkish rule most Orthodox Christians were ignorant of the Christian faith, and St Cosmas went from village to village, and would erect a cross and preach in the open air, just as Wesley did.

So what is a priest?

A priest is an elder and an elder is a priest. But priesthood (eldership) is not "the" ministry. It is one of many ministies in the church, but one of the central aspects of the ministry of priests is "presiding at the eucharist".

Flattery gets you nowhere

Spammers seem to think that their spam is more acceptable if they dress it up with lots of patently insincere flattery. Fortunately WordPress uses Akismet, which seems to have very good spam detection qualities, and so all I need to do is finally delete the comments flagged as spam. I very occasionally look at them, and my eye was caught by this one, which strings together all the flattering cliches ever uttered by any spammers while, as usual, managing to say nothing at all.

Your post is very useful. Thank you so much for providing plenty of useful content.Thanks a lot for sharing these information. The post has also helped a lot. Look forward to your next post Your blog is very useful. Thank you so much for providing plenty of useful content. I have bookmark your blog site and will be without doubt coming back. Once again, I appreciate all your work and also providing a lot vital tricks for your readers. Thanks for the great idea you have post. I'll wait for another info which will you share.

But one wonders at the mentality of someone who appears to think that repetition of such garbage will actually fool the recipient. It doesn't even fool Akismet.

January 19, 2011

Looted ikons

In various conflicts around the world one of the things that happens is that churches are pillaged, and things like ikons are looted. Occasionally, however, they are returned to their rightful home, as in this story: BBC News – Boy George returns Christ icon to Cyprus church:

Musician Boy George has agreed to return to the Church of Cyprus an icon of Christ that came into his possession 11 years after the Turkish invasion.

The former Culture Club singer bought the piece from a London art dealer in 1985 without knowing its origin.

Boy George – real name George O'Dowd – said he was 'happy the icon is going back to its original rightful home'.

In 1974, the year of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, there were also political upheavals in Ethiopia, and in 1994 some ikons and other things that had clearly been looted from churches turned up in a fleamarket in Hatfield, Pretoria.

Looted ikons in a fleamarket in Pretoria

We asked about the prices, but could not afford to buy even one. We would like to have bought the whole lot and tried to find a way to return them to the churches from which they had been stolen.

Crosses as African curios

We wondered about the people who did actually buy such things, and clearly lots of people did, because when we visited later a lot of the church items had gone. Ikons and crosses were not the only thing; there were also well-used liturgical books, presumably in Ge'ez, and censers that appeared to have been home-made.

Looted crosses at Hatfield fleamarket

Anyway, kudos to Boy George for returning stolen property. Would that others would do the same.

January 15, 2011

Renewal in the Orthodox Churches: the diaspora

It is quite unusual for Western theological or missiological journals to publish anything written by Orthodox theologians and missiologists, or about Orthodox Christianity. But Studies in World Christianity (Edinburgh University Press) edited by Alastair Kee has just published an entire issue devoted to the theme "Renewal in the Orthodox Churches: the Diaspora".

Here are abstracts of the articles in Volume 16, Part 3. They are listed below in alphabetical order of the authors of the articles.

Hayes, Stephen, 2010. Orthodox diaspora and mission in South Africa, in Studies in World Christianity, Vol. 16(3). Page 286-303.

The Orthodox diaspora has, paradoxically, spread Orthodox Christianity throughout the world, but has not contributed much to Orthodox mission. Even after the third or fourth generation of immigrants, church services are generally held in the language of the countries from which the immigrants came. This is certainly true of South Africa, where most of the Orthodox immigration has been from Greece and Cyprus, with smaller groups of Russians, Serbs, Bulgarians, Lebanese and Romanians. Though there were immigrants from these countries in southern Africa in the middle of the nineteenth century, it was only at the beginning of the twentieth century that Orthodox clergy arrived, and churches were built, first in Cape Town and then in Johannesburg. It was only in the twenty-first century that clergy began to be ordained locally in any numbers. The churches therefore tended to be ethnic enclaves, and apathetic towards, or even opposed to mission and outreach to other ethnic communities.

Lim, Michelle Sungshin, 2010. Adversity and advance: the experience of the Orthodox Church in Korea, in Studies in World Christianity, Vol. 16(3). Page 304-319.

The development of the Orthodox Church in Korea and her philanthropic works have evolved like a three-act play, ridden with the hardship and sorrow of modern Korean history. That history dates from around 1848 to the late 1980s, evoking a long and sad tragedy narrative of MinJung that began in 1852 and continued to the early 1980s. The "Han" memory of Korean ancestry contains a prolonged painful and shameful past during the collapse of the JoSeon dynasty, which ushered in the imperial Japanese occupation, followed by a brief respite at the time of the Korean independence movement in 1945. Finally in the aftermath of the Korean War from 1950-3 at last, in the name of democracy and industrialisation, many young women were exploited and sacrificed under the two oppressive structures – patriarchy and capitalism – under the rule of the totalitarian government from 1953 to the latter years of the 1980s, including the KwangJu massacre on 18 May 1980.

Makris, G.P., 2010. The Greek Orthodox Church and Africa: Missions between the light of universalism and the shadow of nationalism, in Studies in World Christianity, Vol. 16(3). Page 245-267.

The present article considers the socio-political conditions and the character of the Greek Orthodox Church's missionary activities, taking Nigeria as a case par excellence of the hopes and tensions inherent in the project. As such, the analysis touches only lightly upon the subject of Eastern Orthodox presence in Africa in general, as that would have meant an extended study of the relationship between the Patriarchate of Alexandria, the various Greek immigrant communities, and the multiplicity of local Christianities. The latter are discussed from the point of view of the Church hierarchy in Greece as well as in Nigeria. For this reason the article is meant as an introduction to the issue and should be complemented by ethnographic material from Nigeria.

Persoon, Joachim, 2010. The planting of the Tabot on European soil: the trajectory of the Ethiopian Orthodox involvement with the European continent, in Studies in World Christianity, Vol. 16(3). Page 320-340.

This article relates the concept of the Tabot, the central symbol of divine presence in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in the European diaspora experience. The tabot represents the ark of the covenant in Solomon's temple and is likewise associated with Noah's ark. Thus the Church is conceptualised as facilitating the traversing of the "ocean of troubles" to reach the "safe haven" of the divine presence. This is experienced in an especially intense way in the diaspora context. Beginning with the concept of diaspora the article gives an overview of the history of the establishment of Ethiopian Orthodox Churches in Europe and explores related trajectories. The Church is experiences as a place of memories, and is also a place where the sojourner can feel at home and belong. It facilitates the preserving of identity and culture, re-creating morals and values, and through aesthetics creates a hermeneutic frame of experience, satisfying the "fourth hunger".

Saad, Saad Michael, 2010. The contemporary life of the Coptic Orthodox Church in the United States, in Studies in World Christianity, Vol. 16(3). Page 207-225.