Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 78

September 28, 2011

Tales from Dystopia: SACC Consultation on Racism 11-14 February 1980

At the beginning of 1980 I was asked to be one of four representatives of the Anglican Church (then known as the Church of the Province of South Africa, or CPSA) at a consultation on racism being organised by the South African Council of Churches at Hammanskraal, about 50 km north of Pretoria.

What follows is not a historical account of the consultation, but rather one person's point of view on it. I'm posting it here partly as a link to the preceding posts which are part of a conversation on racism, and partly because it is a historical event that caused some puzzlement to people who weren't there (and even to many who were). Klippies Kritzinger, of the Missiology Department at Unisa, mentioned it in one of the study guides in his course, because one of the results of the consultation was an ultimatum about the formation of a Black Confessing Church, which never came into being. In relation to the preceding posts about racism, the Consultation helped to confirm for me some of the ideas I already had about racism, and to refine them. It was four days of sustained discussion of racism among Christians of different backgrounds and experience.

When I was asked to attend the consultation, I was Director of Training for Ministries in the Anglican diocese of Zululand, living in Melmoth, and responsible for arranging training meetings for self-supporting clergy, and post-ordination training for church-supported clergy. I had been asked to do that by the Bishop, Lawrence Zulu, who had himself previously been a lecturer at the Federal Theological Seminary in Alice.

I mention this because one of the things that the Consultation gave me a new insight into was the nature of interdenominational discourse. People talked past each other because they had little understanding of each other's context and experience. Methodists, for example spoke from the experience of a connexional church, where everything important was decided by a conference that sat like a great octopus waiting to devour its victims. The conference was impersonal. You could address it, but you couldn't talk to it. Anglicans, however, had different experiences based on which diocese they were in. Authority was personal, in that it was represented by a bishop with a human face that you could talk to rather than a conference which wasn't there when the meeting was over.. Some of the things that Methodists said about authority in the church were incomprehensible to Anglicans, who did not experience that degree of bureaucratic centralism – and vice versa. And the experience of Anglicans differed from diocese to diocese. I came from Zululand, where 95% of the clergy and 99% of the laity were black. And so at this Consultation it became clear that people had different concerns based on their denominational structures and experience. Lutherans were concerned about "pastors" and "missionaries", Methodists about centralised structures, Dutch Reformed about "older" and "younger" churches, and so on.

When I was asked to attend the Consultation I was told that its purpose was to evaluate the World Council of Churches' Programme to Combat Racism (WCC PCR) after 10 years. Such consultations were being held throughout the world, arranged by regional councils of churches at the request of the WCC. The Programme to Combat Racism (PCR) had been controversial in South Africa because, among other things, it had a "Special Fund" that made financial grants to movements engaged in guerrilla warfare, including the ANC and PAC of South Africa. At the time the South African Prime Minister, B.J. Vorster, had demanded that the South African denominations that were members of the WCC should resign from that body. We were told that the activities of the PCR were far wider than the Special Fund, but in the event we were never told what the activities of the PCR were. We were therefore in no position to evaluate them, nor were we asked to do so. The group of SACC staff who organised the Consultation organised it as a general discussion of racism in South Africa, with no reference to the PCR. If I had known that, I would have prepared for it quite differently, and so, I suspect, would others who attended. I knew little about the PCR, so waited to be given information before discussing it, but the information was not forthcoming. But we all had experience of racism, and if I had known that is was going to be a general discussion I would have tried to discuss it with others in Zululand before going, to get their opinions.

So I drove the 500 km to Hammanskraal, arriving on the afternoon of 11 February 1980, and registered for the consultation, and was given a huge wad of papers to read, which I started to do before tea.

At tea I met John Warden, another Anglican representative, from the Anglican Diocese of Pretoria, who like me was disturbed that there was no information at all provided about the World Council of Churches' Programme to Combat Racism, apart from the Special Fund. I was concerned that one could not evaluate something about which one had no information, and that we were therefore wasting our time. John said that we were always told that the Programme to Combat Racism was "far wider" than the Special Fund, but in fact nobody knew anything about it, but always spoke of the Special Fund, and it seemed that the Special Fund tail was wagging the dog of the rest of the Programme, though John suspected that there was nothing there, and that in fact the whole thing was a blind.

We got together after tea, and Dan Vaughan, a staff member of the SA Council of Churches, said that the evening would be free for study of papers, but most work would be done in groups, and I was to be a group leader. I didn't want to be. The group leaders were to meet after supper, which meant that there would be far less time to try to digest the material.

So we met to discuss after supper, and I suggested that people should be free to choose which groups they wanted to be in, to discuss whatever subjects interested them, but that was turned down on the grounds that there was a lot of work to get through, and everyone might choose the same group. As a "group leader" I at least was able to choose, and so I chose to be in the group that was discussing manifestations of racism in the church on the first day, and structures and membership of the church on the second. Other groups were to discuss racism in politics, in industry, in education and various other facets of society.

I thought that the decision to allocate people to groups in advance was a bad one. They could have asked everyone to sign up for the things that interested them, and if the result was unbalanced, then ask those who had a second choice to move to one of the groups that was too small. Arbitrary allocation of people to groups meant that someone with valuable knowledge or expertise in one area might not be able to contribute, because they were stuck in a group dealing with a topic that did not interest them and that they knew nothing about.

I chose the group dealing with racism in the church because it seemed to be the most practically useful one. The churches were powerless in most of the other areas, which were entirely beyond their control and they could only hope to influence indirectly. All we could really do would be to pass resolutions "deploring" racism "in the strongest possible terms" (though the strongest terms never actually appeared in such resolutions). In the group dealing with racism in the church it would not only be possible to identify instances and examples of racism, but to try to come up with practical ways of countering or eliminating racism. The ball was in our court. When it came to politics, however, the churches were relatively power-less. The government called the shots, and even discussing it was probably illegal in terms of the Improper Interference Act. We could conceivably have called on members of the church to engage in massive civil disobedience campaigns, but since racism was rife in the church itself the response to that would probably have been zero.

I asked how we could evaluate the Programme to Combat Racism when there was no information on the Programme available to us, and was told that it was available in that among the papers was a copy of an article by Albert van den Heuvel, which mentioned it. I went to my room and tried to read some of the material, but then John Warden came in and talked for a while. He seemed very uptight about it all, and while I had similar misgivings to his about many aspects of this consultation, I saw no reason to get so uptight and threaten to walk out and go home, but perhaps that was because my home was further away than his.

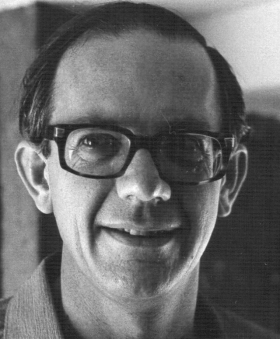

Chris Aitken

Then in walked Chris Aitken, the General Secretary of the Presbyterian Church. I was at school with him at St Stithians, where we started in 1953, and hadn't seen him since he left in 1957.Another one who dropped in was Jimmy Palos, who said he is joining the Council of Churches staff. He said he had met me at Rhodes 12 years ago, but I did not remember meeting him. He seemed a bit unaware of what was happening

The next morning, Tuesday 12 February, I woke up at 5:00, and prayed for the consultation, and read some of the papers. After breakfast we had a Bible study by Stanley Mokgoba, which was a very good analysis of racism from a biblical and theological point of view. He asked why black Christians found themselves more at home with black heathen than with white fellow-Christians and vice versa. He based it on Galatians.

Then John Rees, the former general secretary of the South African Council of Churches and now of the Institute of Race Relations, spoke, and said he did not like the Programme to Combat Racism giving money to guerrilla movements because he regarded that as "tokenism".

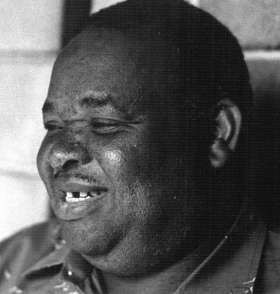

Ben Ngidi

After tea we divided into groups to discuss manifestations of racism in the church. We had a couple of SACC staffers in our group — Ann Hughes, who works for the Dependants Conference, and James Madiba, of the Choir Resources project. Church representatives were David Mosoma, of the Tsonga Presbyterian Church; Brian Jansen, of the Lutheran Church; Ben Ngidi, of the Congregational Church, and Maredi Cheou, a businessman, also of the Lutheran Church.

We divided church activities into various headings, to see how racism is manifested. Ministry – Appointments & Salaries: In general, race is a factor in the appointment of pastors. In salaries, there was generally the same minimum for black and white, but in some churches foreign missionaries have a different pay structure. In some churches, white ministers getting above the minimum would be reluctant to serve in poor black congregations.

Congregational structures: In some churches, race is often a very important factor in determining areas of pastoral oversight. Language is sometimes involved, but is often used as an excuse. Racism is sometimes manifested in church names, e.g. Tsonga Presbyterian Church (shortly after the Consultation the Tsonga Presbyterian Church changed its name to the Evangelical Presbyterian Church, perhaps influenced in this, to some extent, by the consultation). In some churches, the family of a white pastor serving a black congregation worship in another church.

Training for Ministry: Generally different institutions serve different races, thereby not only manifesting but promoting racism. Qualifications for admission to training often show racial bias, e.g. language and academic qualifications.

Administration, Leadership, Finance: The medium of communication and skill advantages possessed by whites can mean that leadership is concentrated in white hands.

Mr Maredi Choeu seemed to have an odd assortment of good and crackpot ideas, and went off into long anecdotes about racism which was in society but not necessarily in the church. He said the architects of apartheid were the children of German missionaries, so he would support any suggestion that the children of missionaries should be sent to their home countries for education, because having grown up among blacks, and gone to school with them, they said they knew blacks. and nobody would dare to contradict them. He gave as an example Dr Eiselen.

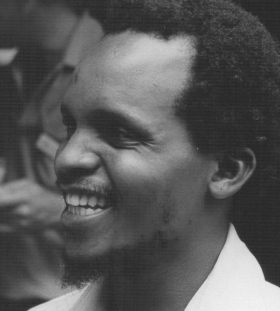

David Mosoma

After lunch we continued in groups, and reported back after tea. John Warden, who was clearly very conservative politically, came to me at tea time and said he was thinking of going home, because one of the black kids in his group was "smouldering" as he put it, and said that violence was the only solution. He said they were supposed to examine attempts to combat racism, and to analyse their success or failure, but they hadn't even listed them, much less analysed them.

One group proposed that there should be a "black confessing church", which sounded to me like starting yet another denomination, and since there were already several thousand black denominations, so I did not how starting yet another one would make any difference. We continued after supper with the same sort of thing.

We began the next morning with a Eucharist, and then I went to breakfast and sat next to Rykie van Reenen, the reporter for Beeld and Rapport, and I told her how much I had enjoyed her reporting of Sacla, which had been accurate and sympathetic, yet the reports in the same papers of the Anglican Church's provincial synod in Grahamstown four months later had been distorted and unremittingly hostile.

As we began Desmond Tutu (then General Secretary of the SACC) said he had been praying, and that the Lord had given him no peace about the fact that the Dutch Reformed Churches were hardly represented at all, and said that he had been given something that he was sure the Lord wanted him to say to our brothers in the Dutch Reformed Churches. He read out this statement, and a number of blacks got up and asked that it be accepted as a message from the consultation as a whole. Roelf Meyer, the only white member of the Dutch Reformed Church present, objected, saying that the Dutch Reformed Churches were on the other side of the struggle. It seemed to me that he was not concerned to be Christian at all, because even if one does perceive them as enemies, we must still love our enemies, but he seemed to be full of bitterness, possibly at the way his own church had treated him.

Desmond Tutu said that the government had stopped talking to him after he had said in Denmark something about boycotting South African coal exports, and though I don't think I heard what he said, there was apparently a great big tizwoz in the press and in government circles about it. In my cynical way I suspect that the fuss was because many cabinet ministers have coal shares, and so they stand to lose out where it hits their own pockets. For the same reason they are not encouraging ethanol as a motor fuel, because they've got their money in Sasol. Personally, I thought that in view of the energy crisis, we should not be exporting coal anyway, even if it were not something that might hurt apartheid.

There was a Bible study by Charles Villa-Vicencio, and then we went into groups again.

Our group was supposed to discuss church structures, organisation and membership, but Ben Ngidi said he thought we ought to discuss the formation of a black confessing church. He said that the time had come to form a black confessing church. I said that if that were so, then we should be leaving this consultation right now, because it would be an admission that racism had defeated us, and that we saw absolutely no point in combating it at all. Certainly it seems to contradict all that we had discussed so far. as it would be attempting to entrench racism in the church. Furthermore, it carried the suggestion that blacks were orthodox because they were black, and that whites were heretical because they were white, and therefore the whole idea is racist from the start. Ben said blacks responded to the gospel from a situation of poverty and oppression, and whites from a position of power and privilege, which I thought was a gross oversimplification — one of yesterday's groups had reported back saying that they thought it was evil that the government should be trying to form a black middle class. But this was, in worldly terms, a middle class consultation. We were a bunch of people who were largely male, largely clergy, and largely middle class.

I gave an example of how members of the black middle class exploited the black poor. In Zululand there was a resettlement are called Nondweni, where people who had been ethnically cleansed from "white" farms and locations near white towns like Vryheid had been dumped. Nondweni was far from any town or other places of employment, so most people there were unemployed and destitute. A few had an income from money sent by relatives who were migrant workers in towns far away. And the very first public building that had been erected in Nondweni was not a school, not a clinic, not a church, but a bottle store. And it was owned by a very respectable black middle-class businessman who was a faithful member of his church. But all the blacks present seemed to think that that was quite legitimate. One said "maybe he gives bursaries", and so showed their middle-class bourgeois nature, and I wanted to laugh.

There was an earnest white American lady who had joined us for the day, whose name I didn't catch, but she spoke to me at lunch and was very patronising. She spoke of "us" and "them", and said that while she agreed with what I was saying, I couldn't tell "them" that, because "they" wouldn't listen to me. I thought that if we could not be honest with each other, and say what we really thought, and perceived people in the group as "us" and "them" on the basis of colour, then we were in fact part of the disease.

And this is the point that led me to tell this story now, because it is the point that impinges on the discussion of "whiteness", and so I think it is worth reflecting upon it a bit more.

Ben Ngidi was dead right when he said that blacks responded to the gospel from a situation of poverty and oppression, and whites from a position of power and privilege. That is still true even today, but it was even more true back then, when the entire legal system and the power structure in the country was geared to entrenching white privilege. But it was also an oversimplification even back then, as the example from Nondweni illustrates. And just as whites tend to easily forget the power and privilege that whiteness gives them, so middle-class people, both black and white, tend to easily forget the power and privilege that middle-classness gives to them. Race is significant in these things, but it is not the only significant thing, which is what the proponents of "Whiteness Studies" seem to suggest.

But the racism of the well-meaning American lady, with her talk of "us" and "them", left me quite gob-smacked. I suppose that she might have been, in American terms, a "white liberal" such as those described in the article by Tim Wise that Roger Saner recommended to me in an earlier comment. But she clearly based the "us" on whiteness, and that struck me as racism. Ben Ngidi and I could argue hammer and tongs, and quite vociferously, but even if we disagreed, we could remain friends, and as South Africans we were far more of an "us" even in our disagreements, than this American who based "us-ness" and "them-ness" purely on skin colour. She is one of the reasons that I resist American analysis of South African problems, and even more American solutions to South African problems.

I began getting a bit of a guilty conscience about this, however, thinking that my reaction might be a bit xenophobic and anti-American. We might bicker among ourselves, but let an outsider come in and start criticising, and we get all defensive, and the outsider becomes a "them" to our "us". But hey (dare I say it?) some of my best friends are Americans.

But still, I do have a similar reaction to Tim Wise — who is he to pontificate about the racism of the likes of Ruth First and Joe Slovo and Jeremy Cronin? He's on about the "white left" you see, and those are the first names that come to mind when I think about the "white left". And "white liberals"? I suppose if you want to find white liberals nowadays you'd find them in the ranks of IDASA, and I doubt that Tim Wise knows any more than I do.

We continued group work in the afternoon, and then I spoke on biblical and theological categories. Ann Hughes accused me of being "academic", and that for me summed up the biggest weakness of the consultation. For many of the participants the Bible and the Christian faith were not existential realities, but are something external to themselves, things which they have had to study in order to pass an exam as a prerequisite to holding a certain office or position within the ecclesiastical structure, but of little use to them in interpreting the reality of their lives. But I saw everything in South Africa in biblical and theological terms. I knew of no other way of dealing with them.

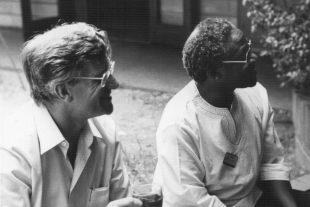

Donald Veysie and Desmond Tutu

The previous day, when one of the groups reported back on the causes of racism, Dr Gomedje from Swaziland commented that the whole report could be summed up in one word — sin. Why do we beat arouind the bush, he asked, why don't we just call racism what it is — sin? And several people sniggered at the naivety of the country hick from Swaziland. Desmond Tutu was quick to rebuke them, and said that that showed that we had nothing different to offer the world, and again at the group leaders' meeting he appealed that the groups should come up with solutions rooted in scripture and prayer, because we were meeting as Christians. But people, certainly in our group, were showing themselves incapable of doing this. Scripture and prayer were "academic" – things you learned about in order to pass exams, but of no existential significance in everyday life.

We finally decided to list a few practical recommendations for combating racism in church structures, organisations and movements. But they all came from my own suggestions and nobody else in the group came up with anything positive or concrete. They just wanted abstractions. I suggested that the basic thing was membership, and that baptism and confirmation instruction should stress the importance of renunciation of the standards of the flesh, of which racism was one, and one of the most significant in South Africa. It should be based on the point that Stanley Mokgoba had made at the beginning – of white Christians feeling more at home with white heathen than with black Christians, and black Christians feeling more at home with black heathen than with white Christians and so on.

Now perhaps this was an example of white privilege. I, being white, could be vocal, and the blacks could sit and listen. But I don't think so. Most of the blacks in the group were people of considerably more power and influence than I was. Maredi Choeu was certainly a good deal richer. I think a more important factor was forcing people into groups not of their own choosing. Most of the people in the church group would rather have been somewhere else, and so getting suggestions for practical action was like drawing teeth. I was the only one who had actually chosen to be there.

When we got back into plenary another group, which had first made the suggestion, called for the immediate formation of a "black militant confessing church", and that led to a heated discussion, which continued after supper. Some were saying that the "black" in the title meant an attitude of mind, others said it meant skin colour and nothing else. I thought that the latter were more honest than the former. It occurred to me that if there was a "black militant confessing church" and if the Christian Leaguers went off and formed the white equivalent, the real confessing church might well emerge from the faithful remnant. But I never got a chance to say that, because it was then decided to exclude "whites" from the debate.

So the whites went off and had coffee, and Jimmy Palos gave us his interpretation of events, which I didn't record, and so have forgotten. John Warden was saying that in a recent survey he had done, the Anglican Church was taking on more of the characteristics of a sect, and I said that that was good, in terms of what our group had said about combating racism as manifested in the church. "Think sect" as Will D. Campbell suggests. The very idea horrified Jimmy Palos.

But if racism was at the foundation of our society, what our society was built on, and we rejected racism as immoral and sinful, then we were already a sect in relation to "mainstream" society, and if we were trying to pretend otherwise we were simply deluding ourselves.

We had Mass the morning, celebrated by Sidwell Thelejane, and I helped him as a server. We resumed in plenary after breakfast, and then discussed a statement that had been produced last night about a black confessing church, and it had been agreed to say that unless there was a meaningful change within a year a black confessing church would be formed. I thought it would be better to discuss such a thing right away, rather than in a year's time, because on it depended the whole raison d'etre of the consultation. And no one said what the change should be, and what would make it "meaningful". There was a growing air of unreality about the whole thing.

We had more group sessions, but these were no more productive than before, which made it clear to me that people should have been free to choose the groups they were in, because they wanted to discuss anything but the topic we were supposed to be discussing, and we never did get round to evaluating the World Council of Churches' Programme to Combat Racism. There was a leaders meeting afterwards to discuss the formation of a continuation committee, which would see that the "decisions" such as they were, were brought to the attention of church leaders, and it was followed by a plenary to elect delegates to go to a meeting of the All-Africa Conference of Churches meeting in Nairobi.

There was some discussion about how to pay for the Consultation, and Desmond Tutu said we could take it out of a fund that was meant to help the poor, as our consultation was intended to help the poor. I commented that all our words were like rain dripping into the sand, and that there had been a lot of talk about the "oppressive structures of society", while the consultation itself was one of them, because the cost of feeding and housing the people who came, in one of the more expensive conference centres, which St Peter's, Hammanskraal is, was paid out of a fund which was supposed to be helping the poor. There was no way that a bunch of well-fed middle-class clergy, meeting for ineffectual discussions, would be of any help at all to the poor. We ourselves were part of the oppressive structures of society, even while we were talkin g about them.

And so we all went home, and I contemplated how to convey the message of the consultation to the people back home. I pictured myself saying to the black bishop and the black archdeacons and the largely black diocesan council: "Unless there is meaningful change within a year, we are going to form a Black Confessing Church."

So was it all a waste of time and money then?

No, I think some good did come from it.

The Tsonga Presbyterian Church adopted a less racist name. The "Black Confessing Church", while it had little meaning for Anglicans, or at least not for those in Zululand, did have some meaning for people in the Dutch Reformed Mission Churches. One of the people who was most concerned about it was Allan Boesak, and he was involved in drawing up the Belhar Confession a couple of years later. So in effect a Black Confessing Church did come into existence among the Dutch Reformed Family of Churches – it is called the Uniting Reformed Church. And it even has some white members.

There are two other aspects of the consultation that are perhaps worth mentioning. I was chatting to David Mosoma at tea between sessions, and told him about the charismatic renewal movement which had affected the whole Anglican Church in Zululand. He was rather surprised, as people outside Zululand tended to think of the charismatic renewal movement as a largely white phenomenon, whereas in Zululand it had started among black Anglicans, and in some cases spread to whites from there. He asked me "where does that leave your Marxist analysis?" And I said "Much where it was before."

This can be seen in a prequel to the consultation, which took place in Zululand a few months before. It was about the bottle store in Nondweni, and it was why I mentioned it in the consultation.

We had had a discussion about it in the Mthonjaneni Deanery, and someone had mentioned that the first public building to be erected in most resettlement areas was a bottle store, and given Nondweni as an example. We eventually drew up a motion for the diocesan synod, very mild and carefully worded, requesting the KwaZulu government to be very careful about issuing liquor licences in areas of high unemployment.

This seized the imagination of people in the diocesan office, and they said that this was a significant motion and they were going to devote a lot of time to it at synod, and that they were thinking of getting some expert on alcoholism to address the synod. And we said, thanks, but no thanks. Our motion is not about alcoholism, it is about exploitation of the poor and people making private profit out of public misery.

And when it was debated at synod people were standing up to say that drinking was a sin, and others were arguing against them and saying no, it is not drinking but drunkenness that is a sin. And we of the Mthonjaneni Deanery tried to bring the debate back on track by saying that it is not about drinking or drunkenness but about exploitation of the poor.

And after one such intervention Mr Gideon Mdlalose, whose brother Frank Mdlalose was Minister of the Interior in the KwaZulu government, which was responsible for the issuing of liquor licences, stood up and said "I am the man. I own the bottle store at Nondweni." And so he confessed in front of the whole synod. But he added that if the bottle store at Nondweni were closed, they would just go to buy liquor at Nqutu, and if that were closed, they would just go on to Dundee. And someone responded, "Yes, but would the school children do that?"

But the purpose of our motion was not to attack Gideon Mdlalose. His name was not mentioned. Nor was Nondweni. We didn't even say "resettlement areas". We just said "areas of high unemployment". The motion was not aimed at individual sinners, to point a finger at them. It was rather aimed, in a very small way, at structural injustice. And what became clear was that the synod was very uncomfortable with discussing structural injustice. It was much more comfortable discussing individual and individualistic sin. It tried ducking and diving every which way – alcoholism, drinking, drunkenness. Anything but systemic exploitation of the poor. And even the consultation on racism did the same thing, not knowing either the place or the people involved. "Maybe he gives bursaries," someone said.

The problem with structural sin is that we are all complicit in it, and it is very difficult to see a way out. It is easier to talk about alcoholism, because we can feel superior to the alcoholic, and can even help people who are trapped in it. But the middle class clergy see the respectable upstanding middle-class exploiter of the poor, and think of the generous amounts he gives to the parish, without which the parish would be in debt, and so it is easier to talk about alcoholism.

At the synod, as the seconder of the motion, I got the penultimate word. I read Nehemiah 5:1-13.

There is no good people complaining that they are oppressed by whites, if there are also black capitalists making a profit and getting prosperous on the miserable degradation of their brothers. Race may indeed play a part in exploitation, but by treating it as if race were the whole problem we blind ourselves to the bigger part, and can fob ourselves off with the excuse that since the people we are exploiting are of the same skin colour as ourselves, it's not racism and therefore OK.

But it's still racism, and it's not OK.

September 26, 2011

Race, class and history

Back in the 1970s there was a school of Marxist historians who attacked the "liberal" school that had flourished 30-40 years earlier.

According to the "liberal" school, the biggest problem in South African society was "race", and in particular "native policy", which they saw as retarding the development of the country.

The Marxist historians believed (with some justification) that the liberal historians had missed the role of capitalism in promoting poverty, oppression and misery. Capitalism was largely invisible to the "liberal" historians, because they assumed that it was part of a normal society, and if they thought about it at all, they thought of it being largely beneficial. Any glitches were simply teething troubles in the development of an industrialising society, and so in an industrial society those problems would be things of the past, just as when a baby learns to chew solid food and enjoy new tastes, it forgets the discomfort of the eruption of milk teeth.

The Marxist historians, or some of them at least, tended to deny that there was such a thing as racism. Racism, to them, was simply a cover up for class warfare, a rationalisation and an excuse for exploitation of the working class. All economic activity, and even government policies were described in terms of "extracting surpluses".

So there were two competing views of South African history — one with the view that the central issue was "race" and the other with the view that the central issue was class.

Now this is a gross over-simplification, and I've been exaggerating the extremes and playing down the middle to try to make the two tendencies clearer, but these tendencies were nevertheless there.

There were other schools of history too — for example, the Afrikaner nationalist school, which tended to dominate school text books in the mid-20th century, and portrayed the main theme of history as the rise and development of the Afrikaner nation, with its own language, culture and territory (which God had given them by displacing the savages who had previously occupied it). Central to this story was the Great Trek.

Marxist historians, on the other hand, tended to see the Great Trek as just one of several similar population migrations (like that of the Ndebele to Matabeleland in the present Zimbabwe) which put the ruling classes in the various groups in a better position to extract surpluses from their own groups or their neighbours.

New History of South Africa by Hermann Buhr Giliomee

New History of South Africa by Hermann Buhr Giliomee

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

More recently there has been, in the true Marxist dialectical pattern, a synthesis. If "liberal" historiography was the thesis, and Marxist historiography the antithesis, then the synthesis combines the two into a new synthesis. And that seems to be the role of New history of South Africa.

But at the moment I'm not just writing a book review, or a review of different schools of historians, but rather recent discourse about "whiteness" (see the previous two posts) seems to indicate a swing of the pendulum, rather than the dialectical pattern of the Marxists. If the focus among the liberal historians was on "race", and that of the Marxist historians was on class, the pendulum now seems to be swinging back to race. Actually even that is an oversimplification, because the very period in which Marxist historiography flourished was also the period in which Black Consciousness flourished.

For the "liberal" historians one of the desirable aims was the creation of a black middle class, which would be more acceptable to the white middle class, and thus South Africa could become a non-racial society in which middle class values would flourish and all would be well.

The Marxist historians thought a better solution would be more power to the working class, and regarded the idea of enlarging the middle class as a backward step, because it would make the middle class more powerful and they would therefore continue to oppress the working class.

Now along comes "Whiteness Studies" which seems to shift the focus back to race.

It seems to emanate mainly from the USA, where it might be easy to identify "whiteness" with being middle class. But even there, I suspect, it is an oversimplification as this article shows: 6 Ways the Rich Are Waging a Class War Against the American People | | AlterNet:

But there's another way of looking at "class war": habitually vilifying the unfortunate; claiming that their plight is a manifestation of some personal flaw or cultural deficiency. Conservatives wage this form of class warfare virtually every day, consigning millions of people who are down on their luck to some subhuman underclass.

The belief that there exists a large pool of "undeserving poor" who suck the lifeblood out of the rest of society lies at the heart of the Right's demonstrably false "culture of poverty" narrative. It's a narrative that runs through Ayn Rand's works. It comes to us in bizarre spin that holds up the rich as "wealth producers" and "job creators."

To bring it back to a Christian perspective, the liberation theologians of the 1970s spoke of a "preferential option for the poor". The proponents of "Whiteness Studies" seem to have a slightly different aim: a preferential option for the non-white.

And the Christian answer to those who like to see the rich as "wealth producers" or "job creators" was, I think, given by G.K. Chesterton, when he said:

For the whole modern world is absolutely based on the assumption, not that the rich are necessary (which is tenable), but that the rich are trustworthy, which (for a Christian) is not tenable. You will hear everlastingly, in all discussions about newspapers, companies, aristocracies, or party politics, this argument that the rich man cannot be bribed. The fact is, of course, that the rich man is bribed; he has been bribed already. That is why he is a rich man.

The whole case for Christianity is that a man who is dependent upon the luxuries of this life is a corrupt man, spiritually corrupt, politically corrupt, financially corrupt. There is one thing that Christ and all the Christian saints have said with a sort of savage monotony. They have said simply that to be rich is to be in peculiar danger of moral wreck. It is not demonstrably un-Christian to kill the rich as violators of definable justice. It is not demonstrably un-Christian to crown the rich as convenient rulers of society. It is not certainly un-Christian to rebel against the rich or to submit to the rich. But it is quite certainly un-Christian to trust the rich, to regard the rich as more morally safe than the poor.

A Christian may consistently say, "I respect that man's rank, although he takes bribes." But a Christian cannot say, as all modern men are saying at lunch and breakfast, "a man of that rank would not take bribes." For it is a part of Christian dogma that any man in any rank may take bribes. It is a part of Christian dogma; it also happens by a curious coincidence that it is a part of obvious human history. When people say that a man "in that position" would be incorruptible, there is no need to bring Christianity into the discussion. Was Lord Bacon a bootblack? Was the Duke of Marlborough a crossing sweeper? In the best Utopia, I must be prepared for the moral fall of any man in any position at any moment; especially for my fall from my position at this moment.

September 23, 2011

Whiteness Studies, Black Consciousness and non-racialism

I only learnt about "Whiteness Studies" a few days ago. Having overcome, to some extent, my initial revulsion towards the name, I thought I'd try to find out a bit more about it. So I used Web search engines to see what I could find.

And the first thing I find is Washington Post Article on Whiteness Class/Whiteness Studies:

Advocates of whiteness studies — most of whom are white liberals who hope to dismantle notions of race — believe that white Americans are so accustomed to being part of a privileged majority they do not see themselves as part of a race.

"Historically, it has been common to see whites as a people who don't have a race, to see racial identity as something others have," said Howard Winant, a white professor of sociology at the University of California at Santa Barbara and a strong proponent of whiteness studies. "It's a great advance to start looking at whiteness as a group."

There are several things to quibble about right there.

In my previous post I tried to understand why I reacted so negatively to the name of the thing.

But reading that makes me react negatively towards the thing itself.

For one thing, it seems that it has been concocted by "white liberals", and, in South Africa, at least "white liberal" is well on its way to being the ultimate insult, and the ultimate negative stereotype. See here, and here, and here.

But by far the bigger problem is that this idea was concocted by Americans.

"Historically, it has been common to see whites as a people who don't have a race, to see racial identity as something others have," said Howard Winant.

That may be true in America, but, historically, it is not true in South Africa. The very foundation of the apartheid ideology was that white people should cling to whiteness and see it as the most important thing about them. The education system was geared to inculcating race consciousness. The whole ordering of society was predicated on that, and it was difficult to get away from it. Actually, I am not even sure if it was true in America, though my perceptions of American society in this respect has been shaped by films like To kill a mocking bird and In the heat of the night. But there do seem to have been some parts of America where it was not true, historically. But the significant point here is not whether it is true or not, but that the proponents of "whiteness studies" think that it is true.

And then the American understanding of "white liberals" probably differs from the South African one, and even the South African caricatures are different.

Steve Biko's critique of the role of white liberals and non-racialism in South Africa is somewhat different too — see White Skins, Black Souls? – Highly recommended critique of white liberals – Steve Biko | Straight Talk:

The role of the white liberal in the black man's history in South Africa is a curious one. Very few black organisations were not under white direction. True to their image, the white liberals always knew what was good for the blacks and told them so. The wonder of it all is that the black people have believed in them for so long. It was only at the end of the 50s that the blacks started demanding to be their own guardians.

Nowhere is the arrogance of the liberal ideology demonstrated so well as in their insistence that the problems of the country can only be solved by a bilateral approach involving both black and white. This has, by and large, come to be taken in all seriousness as the modus operandi in South Africa by all those who claim they would like a change in the status quo. Hence the multiracial political organisations and parties and the "nonracial" student organisations, all of which insist on integration not only as an end goal but also as a means.

The integration they talk about is first of all artificial in that it is a response to conscious manoeuvre rather than to the dictates of the inner soul. In other words the people forming the integrated complex have been extracted from various segregated societies with their in-built complexes of superiority and inferiority and these continue to manifest themselves even in the "nonracial" set-up of the integrated complex. As a result the integration so achieved is a one-way course, with the whites doing all the talking and the blacks the listening. Let me hasten to say that I am not claiming that segregation is necessarily the natural order; however, given the facts of the situation where a group experiences privilege at the expense of others, then it becomes obvious that a hastily arranged integration cannot be the solution to the problem.

I think there was a lot of truth in what Biko said there, but it was also a partial truth. I believe that Biko was speaking in the context of student politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And that was complex, and had reached a unique stage. The Extension of University Education Act had been passed in 1959, which removed most of the black students from the previously "open" universities (which hadn't been all that open anyway). The National Union of South African Students (Nusas) aimed to represent all students in South African universities, but the Afrikanerstudentebond (ASB) dominated the Afrikaans-speaking campuses, on which Nusas had only a tiny membership, if it was not prohibited altogether. During the 1960s the number of students at the segregated tribal colleges grew enormously, which meant that Nusas flourished only on the increasingly-white English-speaking campuses, like Wits, Cape Town, Rhodes and Natal, and most of its leaders were entirely out of touch with the situation on the black campuses, where most of the staff had been formed in the more authoritarian culture of the Afrikaans universities, and so staff and students were increasingly polarised into opposing camps. Where students from the different campuses came together, as at Nusas congresses and conferences, the white students spoke with the freedom of speech they were accustomed to on their campuses, and most of what they said was entirely irrelevant to the conditions experienced by black students on their campuses. And the result was as Biko described.

But before knocking liberalism too much, consider this.

The white English-speaking campuses were not exactly hotbeds of liberalism. True liberals were a small, if sometimes vocal minority. But the universities did have something of a liberal tradition, and were less authoritarian than the Afrikaans-speaking campuses. Students did have more say. On one occasion the SRC of Pottchefstroom University visited Natal University in Pietermaritzburg, and were amazed to discover that the SRC actually controlled the Student Union building where they were meeting, with its cafeteria, hall, meeting rooms and and offices. Student organisations that wanted to hold meetings in the Union approached the SRC to book a venue. In Potchefstroom such a thing was unthinkable in the 1960s (it may be different now). Anyone who wanted to hold a meeting on campus had to have permission from the Rector's office, and the people in the Rector's office would want to be sure that the meetings would be politically and ideologically correct (eg no criticism of apartheid, in education or enywhere else).

Most of the black universities, the "tribal colleges", as they were called, were authoritarian from the start, and so the students who went to them knew nothing else. They did not have Vice-Chancellors, they had Rectors, whose job, as the name implies, was to rule the students and punish the unruly. And in most, instead of treating the students like young adults, the Rector behaved more like the headmaster of an infant school.

The exception to this was Fort Hare, which had originally been a satellite campus of Rhodes University in Grahamstown, segregatecd, but with something of a more liberal tradition. After the university apartheid act, it too switched to the authoritarian model, and also switched to being a tribal college for Xhosa-speaking students. But though the senior staff changed from the liberal to the authoritarian model, the students did not, and generations of students at Fort Hare maintained the liberal tradition, and there were always more student protests there than at other black universities. At least, so Fort Hare students told me in the 1960s. It wasn't white liberals, but black liberals who passed on the liberal tradition.

From about 1970 to 1990 the Black Consciousness ideology propounded by Steve Biko dominated black student discourse. And then came the unbanning of the ANC, and the ANC-backed non-racial ideology came to the fore again. Some people look back rather nostalgically to those days, for example Writing Africa – Tinyiko Sam Maluleke's Blog: Of Liberation and Destructive Ideologies of Struggle Heroism:

One of the greatest liberation heritages of our country, for example, is the Black Consciousness (BC) philosophy. In a context where our grid of criteria for contribution to liberation is the political party and the famous prison-decorated-individual-cum-military-commander, we may miss just how phenomenal Black Consciousness has been for this country. In a context where we are looking for blood-soaked mass events of the "skop-skiet-en-donder" type, as the only milestones in the road to liberation, the more enduring intellectual, psychological and political role of BC can be missed. We all know that the man deserves more recognition than has been given since the advent of democracy, but by BC I mean more than Steve Biko. Nor am I speaking of Azapo or the Black Consciousness Movement — mere political parties which tried to capture (that horrible word again!) the spirit of Black Consciousness.

And some would like Black Consciousness to return: Daily Maverick :: Bring back black consciousness, killed by 'non-racialism':

The fact is the reasons for founding a black consciousness movement have not gone away. Political freedom has been achieved, but Steve Biko spoke of a need, essentially, for black people to define for themselves how the struggle was to be fought. He recognised that the struggle could not be spearheaded by white people, no matter how well-intentioned, simply because they didn't really know what being disenfranchised meant (for a fuller discussion on the roots of Black Consciousness, refer to an earlier column of mine: Black Man, You Are Still Very Alone).

The habit of well-meaning, but ultimately harmful liberals to try to direct the struggle for black people has survived today in the form of efforts to move past race, as if apartheid and all its effects were wiped out in 1994.

"Black consciousness" is still necessary. Black people still need to shape a post-apartheid identity, away from the attentions of those who would seek to capture such discussions for their own ends.

I have a few quibbles with that too. While he doesn't actually use the term "white liberals", there is a kind of assumption that "liberals" are one thing, and "black people" another. For me that has echoes of the the Broederbond's definition of an Afrikaner as someone who was (1) white and Afrikaans speaking, (2) a supporter of the National Party and (3) a member of one of the three Dutch Reformed Churches.

He also sets "Black Consciousness" and "non-racialism" in opposition to each other. Now from reading his other writings, I don't think he is a racist, but I still think he is comparing two fundamentally different things. Non-racialism is not really an ideology.

To understand this, perhaps one needs to go back to the 1950s, when white people generally had a monopoly of political power in Southern Africa. Some white people thought this must change, but gradually. White people who had political power would give a little bit of power to black people, and then a little bit more after a generation or two. Eventually, after maybe a thousand years or so, black people and white people might have equal power in society. That was multiracialism. It was exemplified by the Central African Federation, led by Roy Welenski of the then Northern Rhodesia. He spoke of a racial partnership between black and white, which he likened to the partnership between a horse and rider. So there would be a multiracial parliament, with black members elected by black voters, and white members elected by wehite voters, but even though it could be seen that in the distant future equality might be reached, with equal numbers of black and white MPs, the thought that it could go beyond equality, to "black majority rule" was quite unacceptable to multiracialists.

Non-racialism was the idea of equal representation not of racial groups voting separately, but that everyone should be free to vote for anyone, regardless of race, and that race should not count for anything in political representation or political or civil rights. Non-racialism is not really an ideology, or a philosophy, or a psychological outlook. You could think of yourself as white or black or something else, and it could be of great or little or no importance to you, just as long as you didn't think it gave you more political rights than someone of a different race.

Under the previous regime I was classified as "white" (but I never asked to be — they told me to be). I was also a card-carrying member of the Liberal Party. That made me a "white liberal", or a "White Liberal" if you prefer. But in the term "white liberal" the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and while I acknowledge the separate parts, I don't accept the whole.

The Liberal Party policy was non-racial democracy, and you can read about it here. And you can note that it also made provision for what is now called "affirmative action". But it was a political policy for the ordering of society, and not an ideology, worldview or religion. The Liberal Party had members of many different religions and ethnic backgrounds. They were black, white, coloured, Indian. They were Christian, Hindus, Muslims, Jews, atheists, agnostics and lots of other things besides. Each had their own religious or irreligious or humanist or ideological reasons for belonging and supporting the policy.

In my case, my reasons for supporting the Liberal Party and its policies were primarily theological.

I believed in "one man one vote" because I believed that all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and therefore nobody was better equipped to rule than anyone else.

I believe that God loves all men (male and female, for those who want to pick that particular nit) and that he has no favourites based on race, language, colour or culture. I believe that racism is worse than a heresy and is a false gospel, so that if I detect any traces of it in myself, I must by all means seek to get rid of it. The reasons for this are well expressed by A Message to the people of South Africa, which says, among other things:

Many of our people believe that their primary loyalty must be to their group or tradition or political doctrine, and that this is how their faithfulness will be judged. But this is not how God judges us. Indeed, this kind of belief is a direct threat to the true salvation of many people, for it comes as an attractive substitute for the claims of Jesus. It encourages a loyalty expressed in self-assertion: it offers a way of salvation with no cross. But God judges us, not by our faithfulness to a sectional group but by our willingness to be made new in the community of Christ. We believe that we are under an obligation to state that our country and Church are under God's judgement, and that Christ is inevitably a threat to much that is called 'the South African way of life'. We must ask ourselves what features of our social order will have to pass away if the lordship of Christ is to be fully acknowledged and if the peace of God is to be revealed as the destroyer of our fear.

I believed that when it was first published back in 1968, which was why, though I could understand the reasons for the development of Black Consciousness, I could never regard it as a permanent thing or an ultimate good. And I regard "whiteness studies" as not even of temporary use. We really shouldn't be looking for or clinging to a racial or ethnic identity. The problem in America might be people thinking that they don't have a racial identity when they do. In South Africa I think the problem is that many people have an exaggerated sense racial identity which needs to be pruned.

I believe that the Message to the People of South Africa, or rather the theological thought behind it, is just as important today, when many of my fellow Christians still "believe that their primary loyalty must be to their group or tradition or political doctrine, and that this is how their faithfulness will be judged", only now the group is more likely to be Greeks or Serbs or Russians or Romanians or Bulgarians, though recent outbursts of xenophobia shows that it still applies in other senses as well. But I can walk into a church in my own country, in South Africa, and many people will still regard me as a xenos.

The Message to the People of South Africa is not an old-fashioned historical document. It applies just as much today.

September 17, 2011

Whiteness, whiteliness and White Studies

Reading my blogging friend Cobus van Wyngaard's Facebook page the other day he mentioned "whiteness" and "whiteness studies".

Quick question for those familiar with racial theory and whiteness studies: a common argument in whiteness studies is that not everyone who are white has always been white. The most-common example would be how the Irish became white. Here is the question: have Afrikaners always been white? Was there a time or place when Afrikaners were not white, or not white enough?

I'm not qualified to answer his question, because that was the first time I had ever heard of "whiteness studies", and I was quite surprised by my own reaction to the term. It made me want to puke.

But I can answer the question as someone unversed in "whiteness studies". I can say no, Afrikaners have not always been white. They were not white when they were brown. And the leaders of the white Afrikaners made the brown Afrikaners go and live in their "own" Group Areas so that the children of the white Afrikaners wouldn't be tempted to play with their brown cousins. And that was because the leaders of the white Afrikaners were obsessed with the idea of "whiteness", and thought their "whiteness" made them better than everyone else. And that is why "whiteness" makes me want to puke. And I don't think you need to be familiar with "racial theory" or "whiteness" studies to know that, just history.

Those things on Facebook are difficult to find again, especially when they are more than a day or two old but Cobus has written something on the topic on his blog at How good white people keep white superiority in place | my contemplations:

But as more and more white voices start grappling with the implication of whiteness, this seems to become a strategy of keeping white superiority in place. This is going beyond some of the points Verashni make (although not all), engaging the critique of self, being able to identify the privileges of being white. Yet, when we are challenged to start contributing towards rectifying past injustices, some kind of mumbling follow about how you cannot fight the system, and that it is bigger then one person, and finally that you already know all this, so someone else isn't allowed to point it out to you.

I'm not sure I have completely grasped what Cobus is saying there, but I think my reaction of wanting to puke is that, as Cobus puts it, "this seems to become a strategy of keeping white superiority in place".

Somewhere else Cobus also mentioned a paper by Samantha Vice, on How do I live in this strange place (I hope the link works, because others have linked to it, and it keeps changing, and is quite hard to find). This is a long introspective piece on white guilt and white shame and at the end of it I wondered what on earth could be achieved by such self-absorption. Yes, I know, I started this article by wondering why the word "whiteness" makes me want to puke, and that's pretty introspective right there. But Samantha Vice's article made me long for a breath of fresh air, and I found it here: Daily Maverick :: How to live in this strange place? First, don't run away

As much as we like to malign the escapism that sees certain suburbanites prefer not to live in this country, the likes of tripartite alliance parties do it too. What South Africa doesn't need is for us to shy away from the difficulties by running or opting for "easy" solutions.

Go ahead, read the whole article. Breathe deeply.

So, having breathed deeply of the sound common sense of Sipho Hlongwane, let me plunge once again into the murky waters of introspection and responses to "whiteness".

But first a brief excursion to something Cobus menioned in passing, Stuff white liberals say and do – Verashni Pillay – Mail & Guardian Online. That might be funny, but it also shows that "white liberal" has become a racist stereotype like "lazy kaffir" and "devious coolie", and I'm not sure that racist stereotypes are all that funny in a society where too many people still take them seriously and believe them. The trouble is that many people accept the stereotypes as the reality. If you want to know what a real white liberal is like, as opposed to Pillay's racist caricature, see here Biography of Peter Brown, South African liberal leader | Khanya.

So why do terms like "racial theory" and "whiteness studies" make me want to puke?

Once upon a time there was an organisation called the South African Institute for Race Relations (SAIRR). It was started by people who, if not liberal, did have some liberal tendencies. And the National Party government didn't like some of their reports and the assumptions on which they were based, so they set up a rival body, the South African Bureau for Racial Affairs (SABRA), as a sort of think-tank to fine-tune racial theory.

And that is why terms like "racial theory" make me want to puke, because they remind me of Nazi race theories and SABRA and the theoretical underpinnings of the apartheid ideology.

I grew up in the time when the apartheid ideologists were entrenching themselves in power. Their aim was a totalitarian society in which thinking outside the apartheid box would become unthinkable. But there were still pockets of resistance, and so the ideological battle was still being waged. They tried to play with our minds. They tried to indoctrinate us in school, and in the universities, especially those they controlled.They did it in big ways and in little ways, in grand ways and petty ways.

And among those who resisted were liberals, white and black.

And they got hammered for it.

One could paraphrase what Pastor Martin Niemoller is reputed to have said of resistance to the Nazis:

First they came for the Communists, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a communist

Then they came for the ANC, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a member of the ANC

Then they came for the liberals, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a liberal

Then they came for the trade unions, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a trade unionist

Then they came for the students, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a student.

And before they came for me PW Botha had a stroke and FW de Klerk let everyone out of jail and we could start talking about it.

So what did we set against "racial theory" and "whiteness"?

The idea of non-racial democracy, that's what.

Here are two documents from the sixties that show it:

The manifesto of the Liberal Party

A Message to the people of South Africa

The first is from a political party, the second from the Christian Churches. But both were intended to exorcise the demon of racial theory from our minds and souls and society.

And what I find fascinating as I reread the Liberal Party manifesto after 50 years is that we have a constitution that is very close to the kind of thing the Liberal Party proposed back then. And that many, if not most of the policies of the Liberal Party back then are now policies of the ANC government. Isn't that amazing? A liberal constitution and liberal policies, and all without a liberal in sight?

There is, of course, the small problem of implementation, but that is always the problem with practical politics. And the fact that the ANC, with its Thatcherist policies, is a little further to the right than the Liberal Party was back then.

And the Message to the People of South Africa denounced apartheid and its underpinning of theories of racial identity as worse than a heresy: it was a pseudogospel, seeking salvation by race rather than grace.

And that is why talk of "whiteness" and "racial theory" makes me want to puke.

It reminds me of demons that us old farts spent most of our lives trying to exorcise.

And using those names sounds to me like using Beelzebul to cast out Beelzebul.

And when I see terms like "racial theory" and "whiteness studies" my reaction is the same as that of German Jews when they see a swastika, and are told that it is an ancient Aryan symbol of peace and harmony. Yeah, right.

September 15, 2011

Is blogging in decline?

I was just asked to take part in a survey for Technorati on the "state of the blogosphere", and they asked me to provide statistics about my blogs and things like that.

I had to go hunting for the statistics, and they seem to show that blogging is in decline, or at least it seems to be so for my blogs.

Here are the statistics for this blog, Khanya, for this year so far:

Khanya stats - monthly visitors 2011

My other general blog, Notes from underground, shows a similar decline:

Notes from underground - visitors stats 2011

Our family history blog shows a slight upward trend in recent months, but that may be because we have been more than usually active in family history in the period:

But though there is a decline in page reads and visitors, these blogs seem to maintain their general position in relation to other blogs, which is why I think there may be an across-the-board decline.

But though there is a decline in page reads and visitors, these blogs seem to maintain their general position in relation to other blogs, which is why I think there may be an across-the-board decline.

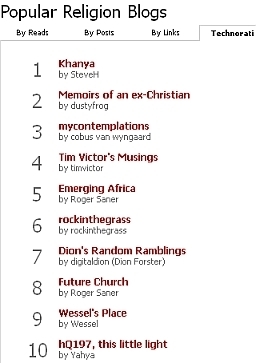

Here, for example are the Amatomu statistics for religious blogs in South Africa.

For the purpose of this exercise, this blog, Khanya, has been at the number 4 position for the last year or so. On rare occasions it has moved up to 3 or down to 5, but it's generally about at the same number 4 position. So if its readers are declining, the average reeadership of all the other blogs in the table must be declining as well.

For the purpose of this exercise, this blog, Khanya, has been at the number 4 position for the last year or so. On rare occasions it has moved up to 3 or down to 5, but it's generally about at the same number 4 position. So if its readers are declining, the average reeadership of all the other blogs in the table must be declining as well.

One problem is that I'm not sure how accurate the Amatomu statistics are. The blog at No 3, Dion's random ramblings, is inactive, and so should have dropped a long way down the list. Dion Forster's new blog, An uncommon path remains inexplicably stuck below it at number 7, even though he posts to it regularly.

On the same page of Amatomu, though not shown in this extract, there is a list of currently popular recent posts. The list is supposted to contain posts that are not more than two days old, ranked by the number of reads in the last hour. But posts from the top three blogs in the list almost never appear there. That means either that a lot of people are reading their old posts, and almost no one is reading their current ones, or that the Amatomu statistics are simply inaccurate, and quite meaningless.

There is also a quite different picture that one gets when one reads the list according to different criteria. The righthand tab shows the list ordered by Technorati "authority". I think that is calculated by the number of links to recent individual posts from other blogs, but I'm not sure about that.

But I think one can draw the same conclusion from that too — if blogs remain in the same relative positions, then the number of people reading blogs has been dropping steadily from the beginning of the year.

Amatomu - religious blogs sorted by Technorati authority

I suspect that one reason for the decline may be the Gadarene rush to sites like Facebook.

Some bloggers I know have been blogging less frequently, and have been putting pages on Facebook instead. The problem is that Facebook is a pretty poor medium for that kind of thing.

I sometimes announce links to my blog posts on Facebook. The problem is that many people prefer to comment on the Facebook link rather than on the blog post itself.

That's OK for ephemeral, trivial or irrelevant comments. But for serious comments, it means that the comments are lost. I can look at the blog post three years later and can see the comments that people made when it was first posted, or at any time since. But the comments that were posted on the link at Facebook are irretrievable, no matter how profound or witty they may have been.

There was a group of bloggers who tried to post a monthly Synchroblog, blogging on the same general topic, and linking to each other's posts. There is a mailing list for regular participants, to discuss what the monthly theme should be, and remind people about it. But then people thought that Facebook was the new and in thing, and started announcing it there instead. As a result, I missed this month's one, because I was busy and spent less time on Facebook. I always read my e-mail first thing in the morning (well, fourth really, but first of the things I do on the Internet). I look at Facebook when I have time. Yes, e-mail reminders come to me from Facebook, but they inevitably get dropped in the "Junk and suspicious mail" queue, which I look at about once a week, mainly to do a mass delete of spam.

So really, people, Facebook has its uses, but it's no substitute for blogging, and for many things, blogging's better.

Anyway, if you'd like to participate in the Technorati "state of the blogosphere" survey, here's the blurb:

We'd love for you to share some information about blogging as your passion or your profession, that we can then share back with you, the bloggers, and everyone who is interested in you. It should take just 15 minutes of your time.

The more responses we get the better the data we can deliver to you, so please share this link with other bloggers. http://www.psasurveys.com/detect.aspx?I.Project=a18214

Look for the full study on technorati.com on Monday, November 7.

I have to say that I found it somewhat annoying.

For example, one question offered the following options:

I blog as part of my full-time job for a company or organization

I blog full-time for the company or organization I work for

I blog full-time for a company or organization that I own

Right now I blog for fun. I would like to make money on my blog some day

I blog occasionally for a company or organization that I own

I blog for fun. I do not make, or plan to ever make, any money on my blog

I am an independent blogger and consider it my full time job

I use my blog to supplement my income, but dont consider it my full time job

My answer was "None of the above", but that wasn't an option.

I find this grossly insulting to people who do the survey. It implies that the only alternative to "making money" is "fun", and so that anyone who is not blogging for money is shallow and only interested in trivialities.

Still, I suppose it is an accurate reflection of the dominant religion of the West — Moneytheism.

September 14, 2011

Blessing of a cross

I left home just after 4:30 am to drive down to St Nicholas in Brixton for the Divine Liturgy, since today is the Feast of the Elevation of the Holy Cross. The Liturgy starts at 6:00, and that is a good time, because it enables one to get there before the traffic gets bad, and by the time it is over the worst of the traffic is finished too.

Afterwards we went to Soshanguve to bless a cross to put on Fr Johannes Rakumako's grave. Fr Athanasius left hss car and came with me — why use two cars when we could fit into one. We met Fr Frumentius in Pretoria — he had brought the cross in a taxi, and it had been made by the monks at the Monastery of the Descent of the Holy Spirit. We fetched Fr Johannes's mother and her grandchild, and went off to the cemetery.

The cross was the suggestion of Fr Pantelejmon, who had arranged the 40-days memorial service for Fr Johannes. He said there should at least be a simple wooden temporary cross, and the monks agreed to make one. And as we drove through the cemetery and saw the increasingly elaborate granite tombstones (some can be seen in the background of the picture), I thought it might not be a bad idea of the wooden cross were the permanent memorial. The rubrics for the service of blessing say: There is no Blessing in the Book of Needs for an ordinary tombstone; Orthodox tradition requires a Cross over the grave, or at the minimum a cross inscribed on the stone.

Blessing of the cross on Holy Cross day. 14 Sep 2011

And so once again we sang the Troparion for the Feast:

O Lord, save Thy people, and bless Thine inheritance.

Grant victories to the Orthodox Christians over their adversaries

And by virtue of Thy Cross preserve Thy habitation.

Afterwards I took Fr Athanasius and Chrysostome to Hatfield station to ride back on the new Gautrain. I haven't been on it yet, but to all accounts it is very pleasant.

September 12, 2011

Obstacles to mission

One of the advantages of house churches is that sometimes new people pop in, which doesn't often happen when the church meets in a school classroom. So when the school where we met in Mamelodi suddenly more than doubled the rental for a classroom on Sundays, we began meeting in the house of one of our oldest members, Christina Mothapo, who is 85. She was finding it a bit of an effort to walk to the school anyway. And since we've been meeting in her house, members of her extended family, who live on the premises, have joined us, which they never did before.

One of the disadvantages, however, is that Orthodox worship really requires a cetain environment that is not apparent in the small cramped sitting room of a council house. For those familiar with Orthodox worship, a couple of ikons propped up against the TV can suggest a great deal more. For those unfamiliar with it, it just seems a rather odd kind of decoration.

So when two of Christina's daughters began joining us regularly, we began to plan to take them to St Nicholas in Brixton. Before our Toyota Venture was stolen five years ago we were able to to that quite frequently, but now it takes two cars, which means covering 400 km on a Sunday. When they start levying tolls on the freeway at 40c per kilometre it will be a lot worse. So it's not something we can do every week, and we checked with Fr Athanasius at St Nicholas to make sure he knew they were coming, and that the full choir would be there.

So last Sunday we went there. I was afraid we would be late, but in fact we were the first to arrive, and Val came a little later, because Christina asked her to take them past the Russian Church in Midrand, which is the most beautiful temple in the diocese. We didn't go there for the service because it is usually all in Slavonic, and though very polished and beautiful, would not be easy for visitors to follow. St Nicholas was founded as a missional parish, and the services are mostly in English, with a few bits in other languages, mainly Greek, Slavonic, Romanian and Afrikaans.

And everything seemed to go extraordinarily well. There were more people in church than usual, and it was even half-full for the second half of Matins, which is unusual. The singing was good, and so we hoped the visitors would have a picture of Orthodox worship as it is meant to be. At the end Fr Athanasius welcomed the visitors, and explained that there were people among them who were not familiar with Orthodox worship, as a kind of hint that people should chat to them and perhaps answer any questions they might have over tea after the service.

Well, we went into the hall for tea, and all hell broke loose.

Three people were engaged in a shouting match. I don't know what it was about, but they sounded very angry. As one song I used to sing in my youth put it, "They'll know we are Christians by our love."

On the way back to Mamelodi Val asked one of the new visitors what she had thought of it, and she said she was put on the spot by one of the parishioners who asked her if she was from Mamelodi, and when she said she was, the parishioner asked her what she thought of Julius Malema, and she was kind of gobsmacked.

So much for being missional.

But then I thought of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who in his book Life together said

Even when sin and misunderstanding burden the communal life, is not the sinning brother still a brother, with whom I, too, stand under the Word of Christ? Will not his sin be a constant occasion for me to give thanks that both of us may live in the forgiving love of God in Jesus Christ? Thus the very hour of my disillusionment with my brother becomes incomparably salutary, because it so thoroughly teaches me that neither of us can ever live by our own words and deeds, but only by that one Word and Deed which really binds us together — the forgiveness of sins in Jesus Christ.

Glory to God for all things!

September 9, 2011

Lest we forget

There are numerous articles about the upcoming anniversary of the crashing of aircraft into the World Trade Center in New York, but spare a thought for the other anniversary. It will also be the seventh anniversary of the death of four Orthodox bishops of Africa, as well as several other people, in a helicopter crash on 11 September 2004.

Among those who died were the Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa Petros VII, Metropolitan Chrysostomos of Carthage, Metropolitan Ireneus of Pelusim and Bishop Nectarios of Madagascar. Seventeen people were killed altogether, but it is very difficult to find the names of the others.