Morgan Daimler's Blog, page 51

March 6, 2014

Popular fiction and Modern Paganism

I've been pagan for a couple decades now and I've observed a couple trends over that time. One of the most perplexing to me is the way that popular fiction - by which I mean novels, television, and movies - shapes and influences paganism. The reason it perplexes me is because the things that get picked up and absorbed into the pagan paradigm are often based in plot points and rarely fit well or make sense (to me) in actual practice. I've had friends argue, however, that this reflects a normal growth and evolution within the wider community, creating the dynamic which is modern paganism.

I'll provide a few examples of things that I have noticed and the sources I attribute to them, based on apparent corollary relationships. This isn't a scientific study, just personal observation. Within a few years of the release of the movie The Craft I noticed an upswing in people condemning love magic as dangerous, calling on the made-up deity Manon, and a sudden trend towards people looking for an elemental balance in their groups, either using zodiac signs or affinity to elements. After Practical Magic came out I noticed a huge surge in people claiming to be natural witches. The Mists of Avalon (book and later movie) created a belief in a division between female witches and male druids (exacerbated by another fiction novel marketed as non-fiction), and forehead tattoos . The Charmed television series provided an array of beliefs I've run across in the pagan community, including the belief that magic shouldn't be done for personal gain, that familiars guide and protect new witches, in "whitelighters" as healers, and that each witch has a special power.

Why does any of this matter? Well, what I struggle with is the way that many of these beliefs are not rooted in anything and cannot be explained. When I asked someone telling me that Druids had to be men and I should be a witch why that was so he could only say because it was "how it was always done" even though that isn't true outside of fiction. When I asked someone claiming familiars protect and guide new witches how her cat does that she could not explain except to say that it was what her friend told her. When I asked the woman who was lecturing me about never doing magic for personal gain but only ever to help other people why the old cunningfolk were paid for their services; well she just gave me a dirty look and stormed off. But when I asked the girl telling me that she needed someone who was an "air" person to complete her Circle why she needed elemental balance - what would happen when she had it? Would the group size be limited to 4? What about traditional covens of 13? - she couldn't tell me.

Paganism already suffers from a lack of understanding of our own beliefs and cosmology; many people repeat beliefs by rote not from a place of comprehension. And we should understand what we believe, the meaning and purpose behind what we say. We should know why we do what we do. Grafting on beliefs that are rootless, that have nothing behind them except an author's need to forward or complicate a plotline, does not help us; in fact can only hurt by muddying already misunderstood waters. You can't explain a belief that is based in the writers need to keep their characters from solving things to easily, or which was meant to set up the main conflict of the story. That is fiction - our religions aren't.

I enjoy pagan fiction quite a lot, but I understand it for what it is - entertainment.

I'll provide a few examples of things that I have noticed and the sources I attribute to them, based on apparent corollary relationships. This isn't a scientific study, just personal observation. Within a few years of the release of the movie The Craft I noticed an upswing in people condemning love magic as dangerous, calling on the made-up deity Manon, and a sudden trend towards people looking for an elemental balance in their groups, either using zodiac signs or affinity to elements. After Practical Magic came out I noticed a huge surge in people claiming to be natural witches. The Mists of Avalon (book and later movie) created a belief in a division between female witches and male druids (exacerbated by another fiction novel marketed as non-fiction), and forehead tattoos . The Charmed television series provided an array of beliefs I've run across in the pagan community, including the belief that magic shouldn't be done for personal gain, that familiars guide and protect new witches, in "whitelighters" as healers, and that each witch has a special power.

Why does any of this matter? Well, what I struggle with is the way that many of these beliefs are not rooted in anything and cannot be explained. When I asked someone telling me that Druids had to be men and I should be a witch why that was so he could only say because it was "how it was always done" even though that isn't true outside of fiction. When I asked someone claiming familiars protect and guide new witches how her cat does that she could not explain except to say that it was what her friend told her. When I asked the woman who was lecturing me about never doing magic for personal gain but only ever to help other people why the old cunningfolk were paid for their services; well she just gave me a dirty look and stormed off. But when I asked the girl telling me that she needed someone who was an "air" person to complete her Circle why she needed elemental balance - what would happen when she had it? Would the group size be limited to 4? What about traditional covens of 13? - she couldn't tell me.

Paganism already suffers from a lack of understanding of our own beliefs and cosmology; many people repeat beliefs by rote not from a place of comprehension. And we should understand what we believe, the meaning and purpose behind what we say. We should know why we do what we do. Grafting on beliefs that are rootless, that have nothing behind them except an author's need to forward or complicate a plotline, does not help us; in fact can only hurt by muddying already misunderstood waters. You can't explain a belief that is based in the writers need to keep their characters from solving things to easily, or which was meant to set up the main conflict of the story. That is fiction - our religions aren't.

I enjoy pagan fiction quite a lot, but I understand it for what it is - entertainment.

Published on March 06, 2014 05:14

March 4, 2014

Danu

Danu is an obscure figure who appears only a handful of times in Irish mythology, and always under the genetive form of the name: "Danann" or "Danand". This has led many to suggest that the name of the Goddess is a reconstruction based off of the name Tuatha Dé Danann, which is often translated as "people of the goddess Danu". Tuatha Dé Danann itself may be a term added later by the Irish monks to differentiate the native Irish Gods from the biblical characters referred to as "Tuatha Dé" (People of God) in the writings, making the subject slightly more complicated.

Although many people assume Danann only shows up briefly in the Lebor Gabala Erenn (LGE), she does also make a couple appearances in the Cath Maige Tuired: "The women, Badb, Macha, Morrigan and Danann offered to accompany them." and "the three queens, Ere, Fotla and Banba, and the three sorceresses, Badb, Macha and Morrigan, with Bechuille and Danann their two foster-mothers" (Gray, 1983). It is possible that the second reference is a transcription error and should read "Dinann" which would mean the list included Be Chuille and Dinann the two daughters of Flidais listed as she-farmers in the LGE, something that would make more sense in the context of the reference, however the first appearance seems to stand alone. It's also worth noting that genealogies in the mythology are extremely convoluted between sources, so it is also possible based on the way that one redaction of the LGE describes "Danand" as a daughter of Flidais, and later says it is Dana, not Flidais, who is Bechuille's mother, that the reference in the Cath Maige Tuired reflects a different understanding of the Goddesses. In the LGE Danu is described as "mother of the Gods" and in some versions is equated to Anu, one of the Morrignae and a daughter of Ernmas (Macalister, 1941). Although in different versions Anu is listed as the seventh daughter of Ernmas, making Danu/Anu a sister to the three Morrignae rather than one of their number. We see her equated to Morrigu and listed as the mother of three sons by her own father as well as mother of all the Gods, for example, here: "The Morrigu, daughter of Delbaeth, was mother of the other sons of Delbaeth, Brian, Iucharba, and Iuchair : and it is from her additional name "Danann" the Paps of Ana in Luachair are called, as well as the Tuatha De Danann." (Macalister, 1941). She is sometimes also equated to Brighid because both are listed in different places as the mother of the three sons of Tuireann. It is possible that Danu was a name used for Anu, the Morrigu or Brighid, but is also possible that the later references to Danu were added in by monks seeking to give Danu more legitimacy as an important factor among the Gods. The third possibility, of course, is that there were originally regional variations of the stories that placed different Goddess in the same role depending on which Goddess mattered in what region and the attempt to unify these stories created the muddy waters we have today.

Elsewhere in literature Danu is described as a goddess and druidess (O hOgain, 2006). She is sometimes called the mother of the Gods but in other places is associated specifically with the three Gods of skill (O hOgain, 2006). It is extremely difficult to sort out any coherent list of her possible parentage, siblings, or children. Very little personal information is attributed to her that is not elsewhere applied to someone else, leading me to suspect that at least part of her story was grafted on at a later time.

Many modern authors associate her with the Welsh Don and with continental Celtic Goddesses based on the widespread use of the root word for her name Dánuv, which is associated, for example, with the Danube river. the name Danu itself seems to come from the Proto-Indo-European word for river*. She has associations with both rivers and as a Goddess of the earth; she likely was originally a river Goddess whose focus later shifted to the earth (O hOgain, 2006).

In modern myth we can find many new stories that include Danu; these are by nature based on the individual's personal inspiration. Alexei Kondratiev wrote an essay called 'Danu and Bile: the primordial parents?' where he links Danu and Bile as a likely pairing that could represent the parents of the Gods. Similarly Berresford Ellis also sees Danu and Bile as a pairing. Some modern pagans and Druids have created elaborate creation stories involving these two and internet sources will list Danu as the mother of deities like Cernunnos and an Dagda. It is best to bear in mind the lack of substantial historic evidence relating to this Goddess and take much of the modern myth and information for what it is.

Creating a relationship with this Goddess would be challenging and would rely on personal intuition to a great degree. The lack of substantial information and mythology means we have only hints to work with. She is a river Goddess. She is a land Goddess. She is a mother of many children and a druidess. Beyond this, let your own imbas guide you.

References

Gray, E., (1983) Cath Maige Tuired

O hOgain, D., (2006). The Lore of Ireland

MacAlister, R., (1941) Lebor Gabala Erenn, volume 4

* http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?t...

Although many people assume Danann only shows up briefly in the Lebor Gabala Erenn (LGE), she does also make a couple appearances in the Cath Maige Tuired: "The women, Badb, Macha, Morrigan and Danann offered to accompany them." and "the three queens, Ere, Fotla and Banba, and the three sorceresses, Badb, Macha and Morrigan, with Bechuille and Danann their two foster-mothers" (Gray, 1983). It is possible that the second reference is a transcription error and should read "Dinann" which would mean the list included Be Chuille and Dinann the two daughters of Flidais listed as she-farmers in the LGE, something that would make more sense in the context of the reference, however the first appearance seems to stand alone. It's also worth noting that genealogies in the mythology are extremely convoluted between sources, so it is also possible based on the way that one redaction of the LGE describes "Danand" as a daughter of Flidais, and later says it is Dana, not Flidais, who is Bechuille's mother, that the reference in the Cath Maige Tuired reflects a different understanding of the Goddesses. In the LGE Danu is described as "mother of the Gods" and in some versions is equated to Anu, one of the Morrignae and a daughter of Ernmas (Macalister, 1941). Although in different versions Anu is listed as the seventh daughter of Ernmas, making Danu/Anu a sister to the three Morrignae rather than one of their number. We see her equated to Morrigu and listed as the mother of three sons by her own father as well as mother of all the Gods, for example, here: "The Morrigu, daughter of Delbaeth, was mother of the other sons of Delbaeth, Brian, Iucharba, and Iuchair : and it is from her additional name "Danann" the Paps of Ana in Luachair are called, as well as the Tuatha De Danann." (Macalister, 1941). She is sometimes also equated to Brighid because both are listed in different places as the mother of the three sons of Tuireann. It is possible that Danu was a name used for Anu, the Morrigu or Brighid, but is also possible that the later references to Danu were added in by monks seeking to give Danu more legitimacy as an important factor among the Gods. The third possibility, of course, is that there were originally regional variations of the stories that placed different Goddess in the same role depending on which Goddess mattered in what region and the attempt to unify these stories created the muddy waters we have today.

Elsewhere in literature Danu is described as a goddess and druidess (O hOgain, 2006). She is sometimes called the mother of the Gods but in other places is associated specifically with the three Gods of skill (O hOgain, 2006). It is extremely difficult to sort out any coherent list of her possible parentage, siblings, or children. Very little personal information is attributed to her that is not elsewhere applied to someone else, leading me to suspect that at least part of her story was grafted on at a later time.

Many modern authors associate her with the Welsh Don and with continental Celtic Goddesses based on the widespread use of the root word for her name Dánuv, which is associated, for example, with the Danube river. the name Danu itself seems to come from the Proto-Indo-European word for river*. She has associations with both rivers and as a Goddess of the earth; she likely was originally a river Goddess whose focus later shifted to the earth (O hOgain, 2006).

In modern myth we can find many new stories that include Danu; these are by nature based on the individual's personal inspiration. Alexei Kondratiev wrote an essay called 'Danu and Bile: the primordial parents?' where he links Danu and Bile as a likely pairing that could represent the parents of the Gods. Similarly Berresford Ellis also sees Danu and Bile as a pairing. Some modern pagans and Druids have created elaborate creation stories involving these two and internet sources will list Danu as the mother of deities like Cernunnos and an Dagda. It is best to bear in mind the lack of substantial historic evidence relating to this Goddess and take much of the modern myth and information for what it is.

Creating a relationship with this Goddess would be challenging and would rely on personal intuition to a great degree. The lack of substantial information and mythology means we have only hints to work with. She is a river Goddess. She is a land Goddess. She is a mother of many children and a druidess. Beyond this, let your own imbas guide you.

References

Gray, E., (1983) Cath Maige Tuired

O hOgain, D., (2006). The Lore of Ireland

MacAlister, R., (1941) Lebor Gabala Erenn, volume 4

* http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?t...

Published on March 04, 2014 06:05

February 27, 2014

Interfaith and Workshop plans

Today's blog will be a brief one, as my daughter has a same day surgery procedure tomorrow and I have a lot to do today, but I read an interesting blog by Jason Mankey discussing his views on interfaith work which he ended by saying that he prefers to focus on building within the pagan community rather than working on interfaith outside it.

By definition interfaith work is rooted in looking for common ground between diverse religions. Ideally it goes beyond tolerance and nurtures acceptance and the acknowledgement of commonalities. For my own part I think understanding and tolerance are the first step we need to achieve before we start working on anything more grand. With so much work left to do in even getting people to understand what reconstructionism really is, I worry about putting the cart before the horse by emphasizing the common ground we share with other groups.

Interfaith of all sorts is a something I find to be very important, not only so I can learn about other traditions but so I can give a voice to mine. I see interfaith work as a chance to educate others about my beliefs and traditions, whether those others are monotheists or other pagans. The goal of education is simply to spread sound information to dispel the fear and mistrust that comes from ignorance. Whether people like what I do, or agree with it, is inconsequential to me if they can come to a place of understanding and tolerance similar to what I have for them. And I think that interfaith work, sharing what I really do and why, is essential to the long term success of the both my own community and a wider, diverse pagan community.

For reconstructionists, especially, I think its vital for us to get out there and have a voice. We are a minority within the minority, often misunderstood, maligned, and mocked, and that will only change if we actively work to change it. Ignorance doesn't go away on it's own; ignorance must be changed through action, both the effort of the speaker to teach and the listener to learn. If we don't make that effort, if we don't try, and just remain within our own insular communities then nothing changes. As part of that we also have to work on being more tolerant of those we disagree with.

As a follower of the traditional views about fairies, that viewpoint deserves equal time and respect too. Without a voice the old understandings are lost under the crush of new opinions and trends. And while it may be much easier to be silent, it is ultimately far more expensive.

In the spirit of this, and more widely of my intent to serve my Gods and spirits, I am going to be fairly busy this year at events and conferences. I'm speaking at Connecticut Pagan Pride's Beltane event in April, at ADF's Wellspring event in May, a Morrigan retreat in Massachusetts in June, Connecticut's Pagan Pride Day in September and the Changing Times Changing Worlds conference in November. I'm excited to have so many opportunities to meet people and talk about things I'm passionate about.

By definition interfaith work is rooted in looking for common ground between diverse religions. Ideally it goes beyond tolerance and nurtures acceptance and the acknowledgement of commonalities. For my own part I think understanding and tolerance are the first step we need to achieve before we start working on anything more grand. With so much work left to do in even getting people to understand what reconstructionism really is, I worry about putting the cart before the horse by emphasizing the common ground we share with other groups.

Interfaith of all sorts is a something I find to be very important, not only so I can learn about other traditions but so I can give a voice to mine. I see interfaith work as a chance to educate others about my beliefs and traditions, whether those others are monotheists or other pagans. The goal of education is simply to spread sound information to dispel the fear and mistrust that comes from ignorance. Whether people like what I do, or agree with it, is inconsequential to me if they can come to a place of understanding and tolerance similar to what I have for them. And I think that interfaith work, sharing what I really do and why, is essential to the long term success of the both my own community and a wider, diverse pagan community.

For reconstructionists, especially, I think its vital for us to get out there and have a voice. We are a minority within the minority, often misunderstood, maligned, and mocked, and that will only change if we actively work to change it. Ignorance doesn't go away on it's own; ignorance must be changed through action, both the effort of the speaker to teach and the listener to learn. If we don't make that effort, if we don't try, and just remain within our own insular communities then nothing changes. As part of that we also have to work on being more tolerant of those we disagree with.

As a follower of the traditional views about fairies, that viewpoint deserves equal time and respect too. Without a voice the old understandings are lost under the crush of new opinions and trends. And while it may be much easier to be silent, it is ultimately far more expensive.

In the spirit of this, and more widely of my intent to serve my Gods and spirits, I am going to be fairly busy this year at events and conferences. I'm speaking at Connecticut Pagan Pride's Beltane event in April, at ADF's Wellspring event in May, a Morrigan retreat in Massachusetts in June, Connecticut's Pagan Pride Day in September and the Changing Times Changing Worlds conference in November. I'm excited to have so many opportunities to meet people and talk about things I'm passionate about.

Published on February 27, 2014 06:36

February 25, 2014

One Druid's Magic

I often hear modern Druids saying that Druids today do not do magic, or that if we do it is not truly magic but a kind of positive thinking or aligning with nature. I find the pervasiveness of this thought interesting, especially as the ancient Druids in myth and legend were well known to wield magic of all sorts. Why have we, as modern Druids, chosen to disassociate from that aspect of our practice?

The core of what I believe is based in connection to things beyond myself: Gods, spirits, the land. It is achieved through Truth, nature, and knowledge; that is seeking Truth, studying nature, and nurturing knowledge. I am an Irish reconstructionist and within that I am a Druid because that best describes the role I fulfill for my community. For a long time I also identified as a witch - I still may in some cases when I feel its appropriate, especially in the context of the way I interact with the daoine sidhe - butwhen I talk about magic I most often mean the practice of Druidic magic. I see Druidic magic as a key part of what I do and I feel confident that it is as grounded as my religion is in ancient sources and folklore.

Historically we know that the ancient Irish had many distinct types of magic workers, of which Druids and witches were only two. Generally, and in broad terms, witches were those who worked baneful magic; the word for witch in Irish, bantúathaid, is related to the word túath in its meaning of wicked or perverse, going against the right order. Druids were known to be supporters of the right order and community.

The Tuatha De Danann had both witches and Druids who did magic for them in the battle against the Fomorians and looking at what the Cath Maige Tuired tells us about what each group brings to the fight is enlightening.

"‘Os sib-sie, a druíde,’ ol Luog, ‘cía cumong?’

‘Ní anse,’ ar na druíde. ‘Dobérom-ne cetha tened fo gnúisib no Fomore gonar'fétad fégodh a n-ardou, corus-gonot fou cumas iond óicc bet ag imgoin friu.’

‘And you, druids,’ said Lug, ‘what power?’

‘Not hard to say,’ said the druids. ‘We will bring showers of fire upon the faces of the Fomoire so that they cannot look up, and the warriors contending with them can use their force to kill them.’

‘Os siuh-sie, a Uhé Culde & a Dinand,’ or Lug fria dá bantúathaid, ‘cía cumang connai isin cath?’

‘Ní anse,’ ol síed. ‘Dolbfamid-ne na cradnai & na clochai ocus fódai an talmon gommod slúag fon airmgaisciud dóib; co rainfed hi techedh frie húatbás & craidenus.’

‘And you, Bé Chuille and Díanann,’ said Lug to his two witches, ‘what can you do in the battle?’

‘Not hard to say,’ they said. ‘We will enchant the trees and the stones and the sods of the earth so that they will be a host under arms against them; and they will scatter in flight terrified and trembling.’"

(http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G300...)

As we can see each brought a different power or skill to the battle. The Druids in this case brought rosc catha, battle magic, something we also see attributed to the Morrignae. The witches bring the ability to enchant the earth against the enemy to create fear. In other myths we see Druids using wands to enchant people by changing their shape and to divine the truth of a situation. We know that they were said to use spoken magic to call up ceo draiodheachte, the druidic mist, and the feth fiada, a spell of invisibility. Druids could influence the weather, divine the future and the truth of the present, bless, curse, and create illusions.

To me magic is an intrinsic part of the role of Druid and it is one I embrace. It fills the stories of Druids in myth and folklore and shapes how the ancient Druids in the stories were said to interact with their world. While witchcraft is often a personally oriented practice that has its own unique focus based in charms and spells, Druidic magic is broader and more intimately connected to understanding and manipulating the connections we have to everything around us. It is about standing in your personal power and using that power to influence things and exert your will.

Magic may not be important or central to all Druids, but I think we do ourselves a disservice as a community to dismiss it entirely. There is a long and rich history of magic in Irish paganism and in the modern era that often reflects or echos older stories of Druidic magic; that reflection should be honored. Th eold stories and modern folk magic give us the root material to work with to create a viable modern approach to magic that is uniquely Irish, pagan, and Druidic. For some of us Druidic magic is essential to what we do, and that should be respected as much as the choice not to follow that path should be respected.

The core of what I believe is based in connection to things beyond myself: Gods, spirits, the land. It is achieved through Truth, nature, and knowledge; that is seeking Truth, studying nature, and nurturing knowledge. I am an Irish reconstructionist and within that I am a Druid because that best describes the role I fulfill for my community. For a long time I also identified as a witch - I still may in some cases when I feel its appropriate, especially in the context of the way I interact with the daoine sidhe - butwhen I talk about magic I most often mean the practice of Druidic magic. I see Druidic magic as a key part of what I do and I feel confident that it is as grounded as my religion is in ancient sources and folklore.

Historically we know that the ancient Irish had many distinct types of magic workers, of which Druids and witches were only two. Generally, and in broad terms, witches were those who worked baneful magic; the word for witch in Irish, bantúathaid, is related to the word túath in its meaning of wicked or perverse, going against the right order. Druids were known to be supporters of the right order and community.

The Tuatha De Danann had both witches and Druids who did magic for them in the battle against the Fomorians and looking at what the Cath Maige Tuired tells us about what each group brings to the fight is enlightening.

"‘Os sib-sie, a druíde,’ ol Luog, ‘cía cumong?’

‘Ní anse,’ ar na druíde. ‘Dobérom-ne cetha tened fo gnúisib no Fomore gonar'fétad fégodh a n-ardou, corus-gonot fou cumas iond óicc bet ag imgoin friu.’

‘And you, druids,’ said Lug, ‘what power?’

‘Not hard to say,’ said the druids. ‘We will bring showers of fire upon the faces of the Fomoire so that they cannot look up, and the warriors contending with them can use their force to kill them.’

‘Os siuh-sie, a Uhé Culde & a Dinand,’ or Lug fria dá bantúathaid, ‘cía cumang connai isin cath?’

‘Ní anse,’ ol síed. ‘Dolbfamid-ne na cradnai & na clochai ocus fódai an talmon gommod slúag fon airmgaisciud dóib; co rainfed hi techedh frie húatbás & craidenus.’

‘And you, Bé Chuille and Díanann,’ said Lug to his two witches, ‘what can you do in the battle?’

‘Not hard to say,’ they said. ‘We will enchant the trees and the stones and the sods of the earth so that they will be a host under arms against them; and they will scatter in flight terrified and trembling.’"

(http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G300...)

As we can see each brought a different power or skill to the battle. The Druids in this case brought rosc catha, battle magic, something we also see attributed to the Morrignae. The witches bring the ability to enchant the earth against the enemy to create fear. In other myths we see Druids using wands to enchant people by changing their shape and to divine the truth of a situation. We know that they were said to use spoken magic to call up ceo draiodheachte, the druidic mist, and the feth fiada, a spell of invisibility. Druids could influence the weather, divine the future and the truth of the present, bless, curse, and create illusions.

To me magic is an intrinsic part of the role of Druid and it is one I embrace. It fills the stories of Druids in myth and folklore and shapes how the ancient Druids in the stories were said to interact with their world. While witchcraft is often a personally oriented practice that has its own unique focus based in charms and spells, Druidic magic is broader and more intimately connected to understanding and manipulating the connections we have to everything around us. It is about standing in your personal power and using that power to influence things and exert your will.

Magic may not be important or central to all Druids, but I think we do ourselves a disservice as a community to dismiss it entirely. There is a long and rich history of magic in Irish paganism and in the modern era that often reflects or echos older stories of Druidic magic; that reflection should be honored. Th eold stories and modern folk magic give us the root material to work with to create a viable modern approach to magic that is uniquely Irish, pagan, and Druidic. For some of us Druidic magic is essential to what we do, and that should be respected as much as the choice not to follow that path should be respected.

Published on February 25, 2014 10:39

February 20, 2014

Goibhniu

"Goibniu who was not impotent in smelting," - Lebor Gabala Erenn

Goibniu, or Goibhniu is the Irish God of smithcraft equated to the Welsh Gafannon. His name is derived from the word for smith; Old Irish gobha, Modern Irish gabha (O hOgain, 2006). It is said that he could forge a weapon with only three blows from his hammer (Berresford Ellis, 1987). Goibniu has two brothers, Credne the wright and Luchtne (or Luchtar) the carpenter, forming a trinity of crafting Gods. The three often work together to forge the weapons of the Gods, with each one making a part of the whole. According to the Lebor Gabala Erenn (LGE) Dian Cecht was also his brother and they were all sons of Esarg: "Goibniu and Creidne and Dian Cecht and Luichtne, the four sons of Esarg" (Macalister, 1941). Indeed the four are mentioned together at several points in the LGE such as: "In his [Nuada's] company were the craftsmen, Goibniu the smith and Creidne the wright and Luichne the carpenter and Dian Cecht the leech." (Macalister, 1941).

Goibniu was the preeminent smith of the Tuatha De Danann who made weapons in particular. Before the battle of Maige Tuired Goibniu is asked what he will contribute.

"And he [Lugh] asked his smith, even Goibniu, what power he wielded for them?

‘Not hard to say’, quoth he. ‘Though the men of Erin bide in the battle to the end of seven years, for every spear that parts from its shaft, or sword that shall break therein, I will provide a new weapon in its place. No spearpoint which my hand shall forge’, saith he, ‘shall make a missing cast. No skin which it pierces shall taste life afterwards. That has not been done by Dolb the smith of the Fomorians. I am now [gap: meaning of text unclear/extent: one word] for the battle of Magh Tuired’." (Stokes, 1926)

During the battle against the Fomorians he made peerless spears that never missed and killed whoever they hit, excluding only himself. We learn the latter fact after Brighid's son by Bres, Ruadan, goes to the forge, takes one of Goibniu's spears and wounds him with it, only to have the smith turn around and kill the would be assassin with the same spear. Goibniu is taken to Dian Cecht's healing well and recovers.

Goibniu had a special drink, a mead or ale called the fled Goibnenn, that conveyed the gift of youth and immortality to the Tuatha De Danann (O hOgain, 2006). This drink is sometimes called the feast of Goibniu and is said in some sources to cure disease (Monaghan, 2004). He also owned a cow who gave endless milk (O hOgain, 2006).

He also has some association with healing according to the St. Gall Incantation in which he is invoked to remove a thorn, possible also a reference to healing a battle wound:

"...dodath scenn toscen todaig rogarg fiss goibnen aird goibnenn renaird goibnenn ceingeth ass:-

very sharp is Goibniu’s science, let Goibniu’s goad go out before Goibniu’s goad!" (Stokes, 1901)

He is also appealed to for protection in some early Irish charms which call on the art of Goibniu (O hOgain, 2006). This may relate to the idea that the being that created the weapon which caused the injury had power over the injury caused, something that we see in the charms relating to elf-shot.

Goibniu is especially associated with Cork, and in particular with Aolbach (Crow Island) on Beara peninsula (O hOgain, 2006). He was said to have his forge there and to keep his magic cow in that area. Other folklore associates him with county Cavan and the Iron mountains there (Monaghan, 2004). In later Irish mythology Goibniu became Gobhan Saer, a smith and architect of the fairies (Berresford Ellis, 1987).

In modern practice Goibniu is still seen as a smith God, but he also has overtones associated with the Otherworld and the sidhe, as do most of the Tuatha De. He could be called on to heal injuries caused by bladed weapons and possibly also by other weapons, and might be called on in conjunction with his two brothers by those who create with metal. I have called on him to bless weapons. Offerings to him might include beer, ale, or mead; I often offer him water, personally, as to me it makes sense to offer something cooling and refreshing to a God of the hot forge.

References:

O hOgain, D (2006). The Lore of Ireland

Stokes, W., (1901). Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus : a collection of old-Irish glosses, scolia, prose, and verse

Berresford Ellis, P., (1987). A Dictionary of Irish Mythology

Macalister, R., (1941). Lebor Gabala Erenn

Monaghan, P., (2004). The encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore

Stokes, W., (1926). The Second Battle of Moytura

Goibniu, or Goibhniu is the Irish God of smithcraft equated to the Welsh Gafannon. His name is derived from the word for smith; Old Irish gobha, Modern Irish gabha (O hOgain, 2006). It is said that he could forge a weapon with only three blows from his hammer (Berresford Ellis, 1987). Goibniu has two brothers, Credne the wright and Luchtne (or Luchtar) the carpenter, forming a trinity of crafting Gods. The three often work together to forge the weapons of the Gods, with each one making a part of the whole. According to the Lebor Gabala Erenn (LGE) Dian Cecht was also his brother and they were all sons of Esarg: "Goibniu and Creidne and Dian Cecht and Luichtne, the four sons of Esarg" (Macalister, 1941). Indeed the four are mentioned together at several points in the LGE such as: "In his [Nuada's] company were the craftsmen, Goibniu the smith and Creidne the wright and Luichne the carpenter and Dian Cecht the leech." (Macalister, 1941).

Goibniu was the preeminent smith of the Tuatha De Danann who made weapons in particular. Before the battle of Maige Tuired Goibniu is asked what he will contribute.

"And he [Lugh] asked his smith, even Goibniu, what power he wielded for them?

‘Not hard to say’, quoth he. ‘Though the men of Erin bide in the battle to the end of seven years, for every spear that parts from its shaft, or sword that shall break therein, I will provide a new weapon in its place. No spearpoint which my hand shall forge’, saith he, ‘shall make a missing cast. No skin which it pierces shall taste life afterwards. That has not been done by Dolb the smith of the Fomorians. I am now [gap: meaning of text unclear/extent: one word] for the battle of Magh Tuired’." (Stokes, 1926)

During the battle against the Fomorians he made peerless spears that never missed and killed whoever they hit, excluding only himself. We learn the latter fact after Brighid's son by Bres, Ruadan, goes to the forge, takes one of Goibniu's spears and wounds him with it, only to have the smith turn around and kill the would be assassin with the same spear. Goibniu is taken to Dian Cecht's healing well and recovers.

Goibniu had a special drink, a mead or ale called the fled Goibnenn, that conveyed the gift of youth and immortality to the Tuatha De Danann (O hOgain, 2006). This drink is sometimes called the feast of Goibniu and is said in some sources to cure disease (Monaghan, 2004). He also owned a cow who gave endless milk (O hOgain, 2006).

He also has some association with healing according to the St. Gall Incantation in which he is invoked to remove a thorn, possible also a reference to healing a battle wound:

"...dodath scenn toscen todaig rogarg fiss goibnen aird goibnenn renaird goibnenn ceingeth ass:-

very sharp is Goibniu’s science, let Goibniu’s goad go out before Goibniu’s goad!" (Stokes, 1901)

He is also appealed to for protection in some early Irish charms which call on the art of Goibniu (O hOgain, 2006). This may relate to the idea that the being that created the weapon which caused the injury had power over the injury caused, something that we see in the charms relating to elf-shot.

Goibniu is especially associated with Cork, and in particular with Aolbach (Crow Island) on Beara peninsula (O hOgain, 2006). He was said to have his forge there and to keep his magic cow in that area. Other folklore associates him with county Cavan and the Iron mountains there (Monaghan, 2004). In later Irish mythology Goibniu became Gobhan Saer, a smith and architect of the fairies (Berresford Ellis, 1987).

In modern practice Goibniu is still seen as a smith God, but he also has overtones associated with the Otherworld and the sidhe, as do most of the Tuatha De. He could be called on to heal injuries caused by bladed weapons and possibly also by other weapons, and might be called on in conjunction with his two brothers by those who create with metal. I have called on him to bless weapons. Offerings to him might include beer, ale, or mead; I often offer him water, personally, as to me it makes sense to offer something cooling and refreshing to a God of the hot forge.

References:

O hOgain, D (2006). The Lore of Ireland

Stokes, W., (1901). Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus : a collection of old-Irish glosses, scolia, prose, and verse

Berresford Ellis, P., (1987). A Dictionary of Irish Mythology

Macalister, R., (1941). Lebor Gabala Erenn

Monaghan, P., (2004). The encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore

Stokes, W., (1926). The Second Battle of Moytura

Published on February 20, 2014 05:12

February 18, 2014

Invocations, part 2

Continuing with invocations...

Invocation to an Dagda

Red God of Great Knowledge

Horse Lord Allfather

God who is good at all things

an Dagda, I call to you

Invocation to Aine

Queen of the sidhe of Cnoc Aine

Red mare who circles the lake

Lady of Midsummer bonfires

of straw torches and burning wisps

Aine of the harvest

Aine of the summer sun

Aine of the hill

I call to you

Invocation to Grian

Queen of the sidhe of Cnoc Greine

Sister of Aine, daughter of Yew

Lady of the winter solstice

of cold, pale light shining on snow

Grian of the cold winds

Grian of the winter sun

Grian of the hill

I call to you

Invocation to Manannan

Manannan son of Lir

Whose horses are the breaking waves

Whose cattle are the innumerable fish

Whose fertile plains are the ocean waters

Manannan of the cloak

Manannan of the feast of youth

Manannan of the wise counsel

Son of the sea, Lord of the strand

I call to you

Invocation to Goibniu

Goibniu, mightiest of smiths

Bearer of the gift of immortality

Goibniu, God of great skill

Remover of thorns

Goibniu, forger of fierce blades

I call to you

Invocation to Brighid (the poet)

Noble Lady of inspiration

Blessed Brighid of the poets

Inspiring Lady

I call to you

Invocation of Brighid (of the Forge)

Blessed Brighid of the forge

Creator, transformer,

Who shapes raw material

Into form and function

I call to you

Invocation to Brighid (the healer)

Brighid of the healing well,

Brighid of the healing cloak

Brighid of the healing word

I call to you

Invocation to an Dagda

Red God of Great Knowledge

Horse Lord Allfather

God who is good at all things

an Dagda, I call to you

Invocation to Aine

Queen of the sidhe of Cnoc Aine

Red mare who circles the lake

Lady of Midsummer bonfires

of straw torches and burning wisps

Aine of the harvest

Aine of the summer sun

Aine of the hill

I call to you

Invocation to Grian

Queen of the sidhe of Cnoc Greine

Sister of Aine, daughter of Yew

Lady of the winter solstice

of cold, pale light shining on snow

Grian of the cold winds

Grian of the winter sun

Grian of the hill

I call to you

Invocation to Manannan

Manannan son of Lir

Whose horses are the breaking waves

Whose cattle are the innumerable fish

Whose fertile plains are the ocean waters

Manannan of the cloak

Manannan of the feast of youth

Manannan of the wise counsel

Son of the sea, Lord of the strand

I call to you

Invocation to Goibniu

Goibniu, mightiest of smiths

Bearer of the gift of immortality

Goibniu, God of great skill

Remover of thorns

Goibniu, forger of fierce blades

I call to you

Invocation to Brighid (the poet)

Noble Lady of inspiration

Blessed Brighid of the poets

Inspiring Lady

I call to you

Invocation of Brighid (of the Forge)

Blessed Brighid of the forge

Creator, transformer,

Who shapes raw material

Into form and function

I call to you

Invocation to Brighid (the healer)

Brighid of the healing well,

Brighid of the healing cloak

Brighid of the healing word

I call to you

Published on February 18, 2014 05:40

February 13, 2014

Invocations part 1

I'll be honest with you all; when I invoke* deities in ritual or devotional offerings I almost always use extemporaneous invocations. However I've been told that invocations are challenging for many people, so I thought I'd offer a selection of different ones here for a variety of the deities I honor. You'll see pretty quickly the basic pattern I tend to use, and my approach to invocations. I'll include a half dozen here and more next time. Feel free to leave a request for a specific deity in the comments if you'd like to see an invocation for one.

Invocation to Macha

Great Goddess, Mighty Macha,

Clearer of plains

Speaker of prophecy

Lady of the Holy People

I call to you

Warrior and Druidess

Wielder of fierce magic

Queen of the Tuatha De

I call to you

Sun of womanhood

Swifter than steeds

Lady of the Sidhe

I call to you

(each verse above could be used as a stand alone with the first line if preferred)

Invocation of Nuada

Nuada of the Silver Arm

High King of the People of Skill

Bearer of the Shining Sword

Who did not turn from battle

Nuada, I call to you

Invocation to an Morrigan

Queen of battle,

Queen of war

Shape-shifting woman

Raven, wolf, and heifer

Bathing in bloodshed

Offering life or death

Obscurity or glory

Strong shield and

sharp spear point

Morrigan

I call to you

Invocation to Badb

Scald-crow who cries over

the seething battlefield

Who dances on sword points

and washes the clothes of

those doomed to die

Speaker of prophecy

Badb, I call to you

Invocation to Airmed

Healing Goddess

Lady of curing herbs

Gentle Goddess

Lady of the spreading cloak

Wise Goddess

Lady of health and wholeness

One of the three healing Gods

I call to you Airmed

Invocation to Flidais

Flidais, mother to many children

satisfier of the insatiable lover

An abundance of milk

flows out from your herds

Deer and cattle at your hand

Flidais of the soft hair

I call to you

*invoke: 1a : to petition for help or support

2: to call forth by incantation http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio...

Invocation to Macha

Great Goddess, Mighty Macha,

Clearer of plains

Speaker of prophecy

Lady of the Holy People

I call to you

Warrior and Druidess

Wielder of fierce magic

Queen of the Tuatha De

I call to you

Sun of womanhood

Swifter than steeds

Lady of the Sidhe

I call to you

(each verse above could be used as a stand alone with the first line if preferred)

Invocation of Nuada

Nuada of the Silver Arm

High King of the People of Skill

Bearer of the Shining Sword

Who did not turn from battle

Nuada, I call to you

Invocation to an Morrigan

Queen of battle,

Queen of war

Shape-shifting woman

Raven, wolf, and heifer

Bathing in bloodshed

Offering life or death

Obscurity or glory

Strong shield and

sharp spear point

Morrigan

I call to you

Invocation to Badb

Scald-crow who cries over

the seething battlefield

Who dances on sword points

and washes the clothes of

those doomed to die

Speaker of prophecy

Badb, I call to you

Invocation to Airmed

Healing Goddess

Lady of curing herbs

Gentle Goddess

Lady of the spreading cloak

Wise Goddess

Lady of health and wholeness

One of the three healing Gods

I call to you Airmed

Invocation to Flidais

Flidais, mother to many children

satisfier of the insatiable lover

An abundance of milk

flows out from your herds

Deer and cattle at your hand

Flidais of the soft hair

I call to you

*invoke: 1a : to petition for help or support

2: to call forth by incantation http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio...

Published on February 13, 2014 18:13

February 11, 2014

Spiritual Devotion and Small Children

I remember the days, 20 years ago, 15 years ago, when spiritual devotion was an easy, flowing thing. If I wanted to stop and pray, or make an offering, or meditate on something I had the flexibility to do so. If I wanted to spontaneously drive out to a state park or to the ocean, I got in my car and went. If I was invited to attend an event or a group celebration I went. the only limitation I had was my work schedule. My focus when I prayed or conducted a ritual was to make it as perfect as possible. I had scripts to follow and high expectations.

And then, ten years ago, I had my first child, and all that changed. My schedule wasn't my own anymore because there was no telling an infant to wait until I was done or finding that still meditative place in myself with a fussy toddler pulling at my hand. My previous approach to spirituality had been based around my own internal rhythms and patterns; what worked for me and when I felt pulled to do things. I had a very spontaneous spirituality, even in my set devotional work. When I planned things I had time to prep for rituals, to go over exactly what I was going to do until I was sure it could be executed perfectly. But all of that changed when children were involved.

There was a time when I chaffed a bit at the feeling of restriction, especially after my second child, who has several chronic medical issues, was born. The way I did things - the way I had done things for years and years at that point - suddenly had to be completely revised. It was a challenge, to be sure, but I believed from the beginning that it was vitally important that my children be included and that what I was doing be something they could also appreciate instead of something they would see taking my attention away from them.

We learned together how to form an organic approach to devotion and ritual. I had to accept that the idea of perfect prayers, recited with my full attention on worship, were right out the window; with small children you always have some small part of your attention on them and what they are doing. My offerings became more creative and also simpler, and I grew to understand that the Gods and spirits want our best efforts, but our best efforts in that moment not perfection. I re-read the Carmina Gadelica seeing it not as a simple prayer book but as a record of a living tradition practiced by people just like me, mothers praying their devotion within the daily round of feeding their families, bathing their babies, and worrying about the safety of those they loved.

I learned that it was better to try than not to do at all, even if the result was comical or rushed or interrupted. My devotional work became a study in perseverance, a type of devotion in its own way. If my morning prayers are interrupted by a hungry infant I sit down and nurse him and keep right on praying. If my Lughnasa ritual falls on an especially hot day then we celebrate inside so that my younger daughter can participate too without getting sick. We adapt, we work with what we have, and we give the Gods our best effort in that moment. Because I am sure the Gods and spirits - and I know for certain my ancestors - understand about hungry babies, and sick children, about life and human limitations.

Beltane 2013 My reward for adopting this approach is not only being able to continue my devotional practice no matter how chaotic my life may be on any given day, but more importantly inspiring my children to want to do what I do. My oldest daughter came to me of her own accord and asked if we could start saying my night prayers together, so now we do them as a family. They look forward to each holiday as something fun they will participate in, and they are proud to be part of the traditions we celebrate. I look back at myself 20 years ago and I see someone who was free to totally devote herself to her religion; I realize now that I still have that freedom if I choose to see my circumstances as a gift and not a burden.

Beltane 2013 My reward for adopting this approach is not only being able to continue my devotional practice no matter how chaotic my life may be on any given day, but more importantly inspiring my children to want to do what I do. My oldest daughter came to me of her own accord and asked if we could start saying my night prayers together, so now we do them as a family. They look forward to each holiday as something fun they will participate in, and they are proud to be part of the traditions we celebrate. I look back at myself 20 years ago and I see someone who was free to totally devote herself to her religion; I realize now that I still have that freedom if I choose to see my circumstances as a gift and not a burden.

Fragment 216 (modified)As it was,

As it is,

As it shall be

Evermore,

O Ancient Gods

Of Skill!

With the ebb,

With the flow,

O Ancient Gods

Of Skill!

With the ebb,

With the flow. - based on material from the Carmina Gadelica volume 2

And then, ten years ago, I had my first child, and all that changed. My schedule wasn't my own anymore because there was no telling an infant to wait until I was done or finding that still meditative place in myself with a fussy toddler pulling at my hand. My previous approach to spirituality had been based around my own internal rhythms and patterns; what worked for me and when I felt pulled to do things. I had a very spontaneous spirituality, even in my set devotional work. When I planned things I had time to prep for rituals, to go over exactly what I was going to do until I was sure it could be executed perfectly. But all of that changed when children were involved.

There was a time when I chaffed a bit at the feeling of restriction, especially after my second child, who has several chronic medical issues, was born. The way I did things - the way I had done things for years and years at that point - suddenly had to be completely revised. It was a challenge, to be sure, but I believed from the beginning that it was vitally important that my children be included and that what I was doing be something they could also appreciate instead of something they would see taking my attention away from them.

We learned together how to form an organic approach to devotion and ritual. I had to accept that the idea of perfect prayers, recited with my full attention on worship, were right out the window; with small children you always have some small part of your attention on them and what they are doing. My offerings became more creative and also simpler, and I grew to understand that the Gods and spirits want our best efforts, but our best efforts in that moment not perfection. I re-read the Carmina Gadelica seeing it not as a simple prayer book but as a record of a living tradition practiced by people just like me, mothers praying their devotion within the daily round of feeding their families, bathing their babies, and worrying about the safety of those they loved.

I learned that it was better to try than not to do at all, even if the result was comical or rushed or interrupted. My devotional work became a study in perseverance, a type of devotion in its own way. If my morning prayers are interrupted by a hungry infant I sit down and nurse him and keep right on praying. If my Lughnasa ritual falls on an especially hot day then we celebrate inside so that my younger daughter can participate too without getting sick. We adapt, we work with what we have, and we give the Gods our best effort in that moment. Because I am sure the Gods and spirits - and I know for certain my ancestors - understand about hungry babies, and sick children, about life and human limitations.

Beltane 2013 My reward for adopting this approach is not only being able to continue my devotional practice no matter how chaotic my life may be on any given day, but more importantly inspiring my children to want to do what I do. My oldest daughter came to me of her own accord and asked if we could start saying my night prayers together, so now we do them as a family. They look forward to each holiday as something fun they will participate in, and they are proud to be part of the traditions we celebrate. I look back at myself 20 years ago and I see someone who was free to totally devote herself to her religion; I realize now that I still have that freedom if I choose to see my circumstances as a gift and not a burden.

Beltane 2013 My reward for adopting this approach is not only being able to continue my devotional practice no matter how chaotic my life may be on any given day, but more importantly inspiring my children to want to do what I do. My oldest daughter came to me of her own accord and asked if we could start saying my night prayers together, so now we do them as a family. They look forward to each holiday as something fun they will participate in, and they are proud to be part of the traditions we celebrate. I look back at myself 20 years ago and I see someone who was free to totally devote herself to her religion; I realize now that I still have that freedom if I choose to see my circumstances as a gift and not a burden.Fragment 216 (modified)As it was,

As it is,

As it shall be

Evermore,

O Ancient Gods

Of Skill!

With the ebb,

With the flow,

O Ancient Gods

Of Skill!

With the ebb,

With the flow. - based on material from the Carmina Gadelica volume 2

Published on February 11, 2014 07:19

February 6, 2014

An Essay on the Instruction of King Cormaic Mac Airt

There are several Irish texts that offer instructions on how a King should live in order to be a good King, and these texts serve as good instructions for anyone to study on how to live a good honorable life. One of the best of these is the Instruction of King Cormaic Mac Airt, a dialogue that occurs between Cairbre and Cormac, where Cairbre is quizzing Cormac about the proper qualities of a King. The answers given describe the characteristics a King should embody, but these characteristics are equally applicable to any person seeking to live a good life. These characteristics can be divided into two categories: ways that the person should act towards others, and ways that the person should uphold themselves. The dialogue response begins with Cormac describing ways that the King should act in order to uphold his own honor. The first of these is by having good geasa, or ritual taboos that are positive. This could apply to anyone who has a geis on them, if only in the way we choose to look at the ritual taboos that bind us; we can choose to see our taboos as positive or negative and how we react to them shapes their nature on some level making them either a gift or a burden. The next line advises the King to be sober, good advice since drunkenness is often a source of trouble. The King is advised to be an invader as well, which is a slightly more obscure line; however I believe that this advice pertains to ambition and the need for any person to have a healthy sense of what they can achieve. Only by pushing outward and seeking to expand can we truly achieve our own potential. The following lines suggest a good King should have good desires and be affable, telling us that people should seek to want what is best for themselves and have a friendly nature. A good King should be both humble and proud, meaning that we should be humble in knowing our own limits and admitting to our own mistakes but also proud of what we do achieve and owning our own success; only through a balance of these two can true success be found. In the same way we should be quick and steadfast, meaning we should act quickly when speed is needed but also have the stamina to stick with anything and see it through. A good King, or a good Druid, should be a poet, versed in legal lore, and wise, as well as temperate. All of these qualities should be embodied in the King, or person, for them to find the inner strength to live honorably in all these ways, because these external expressions reflect the character within. Cormac also touches on ways that a good King should interact with others, beginning with being generous, decorous, and sociable. These three features all intertwine to support each other, and to support the proper social order where the King sets the tone for the Kingdom, but it is possible for anyone else to also live by these maxims and seek to express these things as well. Along with this go other suggested actions according to Cormac, such as feeding orphans, giving good judgments, raising up the weak, quelling wrongs, and loving truth while hating falsehood, all of which can be embraced by anyone seeking to live in honor. To seek to live these qualities is to seek to live Truth and support the right order of the world. The truth of this statement is seen in the final passage where Cormac describes what will occur in the kingdom of a good King, should he follow all this advice. We see the description of a good King ruling over a fertile land, with oak trees full of acorns, fruitful earth and rivers full of fish. In the same way if we as individuals seek to embody these characteristics and live these actions then we can also bring blessings upon the world we live in.

Published on February 06, 2014 07:55

February 4, 2014

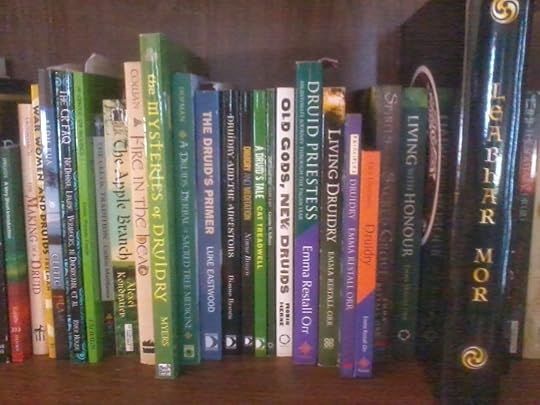

Recommended Reading for Irish Druids

Irish Druid's reading list:

The Mysteries of Druidry by Brendan Myers - a great book that discusses Druidism from a specifically Irish perspective including both history and modern practice

Celtic Flame: An Insider's Guide to Irish Pagan Tradition by Aedh Rua - a greta look at one person's attempt to create a modern Irish pagan tradition. Useful for an Irish Druid on several levels, including ritual structure and thought provoking ideas on theology

The Apple Branch: A Path to Celtic Ritual by Alexei Kondratiev - not Irish specific but a must read fo rthe histrory of the different holidays; also full of important mythology and folklore

The Sacred Isle: Pre-Christian Religions in Ireland by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin - one of my personal favorites, a great look at the pagan Irish and Druids; the author does tend to look for a classical model for the Gods, so some of his ideas should be taken with a grain of salt, but overall very useful.

The Lore of Ireland: An Encyclopaedia of Myth, Legend and Romance by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin - essential quick reference for different Irish material, especially deities, heroes, places, and holidays

The Druid's Primer by L. Eastwood - again not Irish specific but an excellent look at the basic history of Druidism and a possible modern structure for it

Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain by Ronald Hutton - an in depth look at the history of Druidism, particularly the revival period

The World of the Druids by Miranda J. Green - focused more on the history of Celtic religion and Druidism, including archaeological evidence

Druids, Gods & Heroes from Celtic Mythology (World Mythology Series) by Anne Ross - a basic introduction to Celtic mythology

Celtic Heritage by Rees & Rees - an indepth look at Celtic culture

A Druid's Herbal of Sacred Tree Medicine by Ellen Evert Hopman - lots of herbal lore, but also tidbits of Druidic history and lore about the holidays

Druidry and the Ancestors by Nimue Brown - not specifically Irish, but an excellent look at how to incorporate ancestor honoring into modern practice

War, Women, and Druids by Philip Freeman - a concise collection of ancient references relating to Celtic culture including Druids and bards

Druids Sourcebook edited by John Matthews - a collection of a variety of early and later references and articles about Druidism.

I'd also repeat my Irish recon reading list as it includes a lot of the important mythology:

Festival of Lughnasa by Maire McNeill - an in-depth look at the historic and modern celebration of Lughnasa, including a good deal of folklore and mythology

The Lebor Gabala Erenn - the story of the invasions of Ireland by the Gods and spirits and eventually humans.

Cath Maige Tuired - the story of the battle of the Tuatha de Danann with the Fomorians.

the Year in Ireland by K. Danaher - an overview of holidays and folk practices throughout the year.

The Silver Bough (all four volumes) by F. MacNeil - Scottish but extremely useful for understanding folk practices and beliefs

Fairy and Folktales of the Irish Peasantry by Yeats - a look at folklore and belief, important for including the Daoine maithe in your practice

Lady with a Mead Cup by Enright - useful look at ritual structure and society in both Celtic and Norse cultures

Celtic Gods and Heroes by Sjoestedt - discusses both the gods and tidbits of folklore and mythology

I'd suggest my own books as well, but that seems a bit self serving..

The Mysteries of Druidry by Brendan Myers - a great book that discusses Druidism from a specifically Irish perspective including both history and modern practice

Celtic Flame: An Insider's Guide to Irish Pagan Tradition by Aedh Rua - a greta look at one person's attempt to create a modern Irish pagan tradition. Useful for an Irish Druid on several levels, including ritual structure and thought provoking ideas on theology

The Apple Branch: A Path to Celtic Ritual by Alexei Kondratiev - not Irish specific but a must read fo rthe histrory of the different holidays; also full of important mythology and folklore

The Sacred Isle: Pre-Christian Religions in Ireland by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin - one of my personal favorites, a great look at the pagan Irish and Druids; the author does tend to look for a classical model for the Gods, so some of his ideas should be taken with a grain of salt, but overall very useful.

The Lore of Ireland: An Encyclopaedia of Myth, Legend and Romance by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin - essential quick reference for different Irish material, especially deities, heroes, places, and holidays

The Druid's Primer by L. Eastwood - again not Irish specific but an excellent look at the basic history of Druidism and a possible modern structure for it

Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain by Ronald Hutton - an in depth look at the history of Druidism, particularly the revival period

The World of the Druids by Miranda J. Green - focused more on the history of Celtic religion and Druidism, including archaeological evidence

Druids, Gods & Heroes from Celtic Mythology (World Mythology Series) by Anne Ross - a basic introduction to Celtic mythology

Celtic Heritage by Rees & Rees - an indepth look at Celtic culture

A Druid's Herbal of Sacred Tree Medicine by Ellen Evert Hopman - lots of herbal lore, but also tidbits of Druidic history and lore about the holidays

Druidry and the Ancestors by Nimue Brown - not specifically Irish, but an excellent look at how to incorporate ancestor honoring into modern practice

War, Women, and Druids by Philip Freeman - a concise collection of ancient references relating to Celtic culture including Druids and bards

Druids Sourcebook edited by John Matthews - a collection of a variety of early and later references and articles about Druidism.

I'd also repeat my Irish recon reading list as it includes a lot of the important mythology:

Festival of Lughnasa by Maire McNeill - an in-depth look at the historic and modern celebration of Lughnasa, including a good deal of folklore and mythology

The Lebor Gabala Erenn - the story of the invasions of Ireland by the Gods and spirits and eventually humans.

Cath Maige Tuired - the story of the battle of the Tuatha de Danann with the Fomorians.

the Year in Ireland by K. Danaher - an overview of holidays and folk practices throughout the year.

The Silver Bough (all four volumes) by F. MacNeil - Scottish but extremely useful for understanding folk practices and beliefs

Fairy and Folktales of the Irish Peasantry by Yeats - a look at folklore and belief, important for including the Daoine maithe in your practice

Lady with a Mead Cup by Enright - useful look at ritual structure and society in both Celtic and Norse cultures

Celtic Gods and Heroes by Sjoestedt - discusses both the gods and tidbits of folklore and mythology

I'd suggest my own books as well, but that seems a bit self serving..

Published on February 04, 2014 04:59