Jay Sennett's Blog, page 2

November 3, 2018

You: A Transsexual Love Story

To my dearest, dearest transsexual family,

Remember the time you felt a moment of rest, a pause, your body relaxing just ever so much, noticed by you alone?

When, after years of a bolt stiff neck and spine, wary of the next stranger, leery of all those people claiming to be your friends, chary of your body, the hormones and surgeries and studied practicing of the gender of your need all conspired to make you the you were — for that moment at least — always desperate to be?

Did you relax a little more?

Did a piece of the armor fall away?

Did you cry?

Breath a second of relief?

This.

This is always what we’ve wanted. Our human right to relax into each moment of body’s living embrace of time passing.

This is the transsexual agenda: we want to exhale. We’ve too long been blue in the face, seeking permission to breathe.

Well done, I say.

We are very special, long of strength of will and patience.

How can anyone succeed who cannot wait?

We wait for permission to wear the clothes we want, for permission to be called by the name we desire and the pronouns we need, for permission to receive medical care, for permission to live free from humiliations and violence.

Waiting is our greatest super powers. Come at us.

We will outlast all of you.

We seek to inhabit the here and now, free from the interruptions, the interrogations, the inquisitions, some of them life-threatening, brought about by a protrubering adams apple or globular, jingling breasts or a voice too low or one too high, a mincing walk or a barreling gait.

We seek the right to be forgotten in a crowd, to burrow deep down in a body that feels — finally after many years of waiting — like a friend.

In the newness of these moments, blossoming into a new us froman old gender, we have nothing left to fight about.

In this moment our bodies have become home.

We no longer living a short distance from our bodies.

We find ourselves not out there but in here.

Well done my beautiful tribe of Transsexual Waiters and Lurkers and Doers.

Inhale the moment when it first comes to you.

Exhale into your body.

It has been worth it. It will be worth it. Because you live and breath and fight, waiting until the right times arise.

Rejoice and be glad. We were never meant to survive.

November 2, 2018

Sincerely, Your Transgender Friend

Dear Eraserhead,

I checked this morning in the mirror, and guess what? I’m still here. At least as far as I can tell, I appear no more effaced, deleted or canceled than yesterday. Or the day before that. Or even compared to last year.

You seem to find me a threat. There’s not much I can do about that. Only you can control your own mind and thoughts. The same is true for me. And since I can’t control you, I won’t be thinking too much about you.

I most certainly won’t be getting angry with you. Why would I? If I do, then somehow I agree with you. Since only I can disturb my serenity through my thoughts, why would I relinquish my peace of mind to you?

You are not my master. I won’t collude with your pain and suffering by agreeing that I as a transsexual man am the source of your problems, that as a transgender person, I cause you tremendous disruption, and maybe even terror.

I get it. You want to feel safe, to feel happy.

Okay. Sure. If you think rubbing me out or abolishing me or negating me, will make you happy, then by all means my friend, be happy.

Sincerely,

Your Transgender Friend

Your transgender friend, age 2-ish, in an original VW Beetle.

Your transgender friend, age 2-ish, in an original VW Beetle.November 1, 2018

When a Beta Reader Says No

The manuscript, a second volume of my ongoing memoir series, was done and sent to my beta readers. I felt so proud, constructing essays using some of the tools I learned in Julie Otsuka’s Buddha in the Attic and a few essays I studied in the journal APublic Space.

“I like what you’ve written,” one beta reader wrote in an email. “My question is,” she continued. “Who are you writing for?”

Her question floored me. I had countless bylines, varieties of writing experience, two completed screenplays and one completed novel and more than a passing understanding of how the English language works. Not once had a beta reader ask me who I was writing for.

The second volume seemed no different. I was writing for my readers.

Like me, I thought the tired cliches used to describe transsexual experiences like mine bored them. Like me, I thought they wanted a complex narrative about being born female then transitioning to male, and well before the internet, too. Like me, I thought the singular and sole use of the first-person in the emerging, but still small, body of transgender and transsexual literature made them weary.

Didn’t they want second- and third-person pronouns used to explore the difficult, fraught yet wonderful experiences that center around living in a conundrum? (How does a 32-year-old lesbian become a man?)

I know I did. They did, too, right?

I care quite a bit about people reading what I write, reveling in every story people share about how my writing touched them. Crass as it may be, I do want to move people, a nearly impossible task if I’m only writing for myself.

My beta reader’s response set me back on my heels, and longer than I care to admit. Professionals should recover quickly, from even the most devastating feedback.

Something about the style of the manuscript combined with her question forced me to accept an embarrassing truth. I wrote this manuscript for myself, only.

I was that guy on a first date who tires of listening to his date. Enough about you! Let’s talk about me.

I was also the guy who forgot the importance of story telling. Experimental fiction and nonfiction attracted me for a variety of reasons. Narrative structures are usually the first thing to go in experimental writing.

Virginia Woolf has written one of the very best anti-plots in English. Mrs. Dalloway taught me a lot about time in narratives and the arbitrary nature of literary realism.

But Ms. Woolf won’t be remembered ever for her compelling plotting skills.

What I realized after pondering my beta reader’s question, reviewing my dogeared copy of The Story Grid and whining to myself about how so very hard – hard, I say!- writing is, I understood something very important for my career as a writer: people like me, who have had their lives dissected in medical journals, scorned in the media and degraded from the pulpit need well-written stories. Our lives may depend on it.

Axiomatic, I know. But experimental literatures works on the principal that the thing being experimented on has a whole body of positive words somewhere else. Transsexuals like me don’t have the luxury of an already existing body of literature where we are loved and feted and seen for who we are.

How I write anything is a choice, and while I could choose from a variety of tools, I have opted to rewrite every essay using the power of the age-old three-act structure to share my experiences. This kind of storytelling touches us all still.

This article originally appeared at Authors Electric.

October 3, 2018

Do I Write What I Want to Read?

The words read flatly and stunk out loud. A kind of slow-moving gloom descended over me. What had happened to this essay? I worked on it for weeks and rewrote it twice. Another reading out loud confirmed my initial review: the words lay dead on the page.

The culprit eluded me. Rereading no longer worked. I had read it so often the words no longer meant nothing and decided to put it aside and reread Joan Didion’s The White Album.

Her nonfiction work in general and the titular essay of the book in particular changed how American authors write nonfiction essays. “We tell ourselves stories to live,” begins the essay and meanders through Didion’s observations of the late 1960s California. A news story about a woman who deserted her five-year-old daughter on the median of a Los Angeles freeway is juxtaposed with excerpts from her own psychiatric evaluation.

The Summer of Love and the 1960s were for her a complete failure. She had charted the beginnings of this failure in her essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and documented its death in “The White Album.”

Didion’s meticulous details build an impressionistic sense of doom and make a covenant of honesty with the reader. While I may not agree with her conclusions, my disagreements result from how she interprets the evidence she gives, not the evidence itself.

After finishing The White Album I picked up my essay and reread it and discovered my words lacked sensate details, honesty and a compulsion to grind more than one axe. To paraphrase George Orwell (a mentor to Didion), most of the passages lacked all meaning.

The culprit I found in a series of books I had just completed. The Vietnam War colored every detail of my childhood. The nightly news broadcast napalm bombing. Soldiers visited houses on my street. Look and Life magazines published images of children older and younger than me dead and maimed.

As an adult it seemed like most of my friends had brothers and fathers and cousins, sometimes women if they were nurses, who returned afflicted and affected and angry and learned to suffer in silence and alcohol.

I set about understanding the Vietnam War through a reading list that included Halberstam’s The Best and The Brightest, Hue 1968 by Mark Bowden, Bloods: Black Veterans of the Vietnam War by Wallace Terry and War Torn: Stories of War by Women Reporters Who Covered Vietnam by Tad Bartimus. The words in these books educated and persuaded, some more successfully than others. All four relied on first-person interviews to support their narratives.

Michael Herr wrote what many consider the best book about Vietnam and his nonfiction essays in Dispatches affected me deeply, effecting as it did a kind of something in me. That I could not point to how he had created that effect warned me to reread more carefully. I did and then understood why I had only imprecise feelings from his book.

Herr’s writing lacked the skilled precision of Didion, relied on the kind of vague language loathed by Orwell and failed to separate what he thought he should feel about certain actions versus what actually happened.

All of which ended up in my essay.

I had forgotten the important four questions Orwell described in Politics and the English Language.

What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?”

(Re)armed with Didion, Orwell and Hemingway for his directness and utter lack of sentimentality, I have begun rewriting the essay. I’m pleased to say I’ve made great progress and have also begun applying Orwell’s four questions to everything I read.

The experience reminded me of the importance of vigilance and honesty as a writer. My job is to write as truly as I can and get out of the way and resist the urge to explain. Nebulous language must go. Trusting myself as a writer still proves to be a challenge and one I welcome.

This article originally appeared at Authors Electric.

June 1, 2018

Wonderful, Radical Transsexual Acceptance

I wish I could say my path to masculinity followed a straight line from A to B.

I thought it should have done that. But in retrospect, how can any path of identity, particularly a transsexual one for which we have few landmarks and fewer roadmaps, follow a straight line?

Identities move back and forth, shoot out in one direction for long periods of time, only to return to some earlier beginning, but with a renewed understanding of origin stories.

I like my body now. But this hasn’t always been true.

* * *

About two years after I started hormones, I decided to stop taking them. The future I imagined when I first started hormones never materialized. The ease I thought I would feel in my body eluded me. The confidence I saw in other FtMs missed me.

My sexuality was muddled. I had no idea how to date women as a man. They all seemed wary of me, in ways I saw physically, but had no idea how to address.

How do I date women now?

My only positive sexual experiences had been as a butch woman and may have influenced my desire to stop taking hormones.

At least I know how to be butch and date and have sex.

The recriminations began. I taunted myself.

Was I even a man?

If I was, what kind of man was I? Who would want to date a man like me?

Stopping hormones seemed like the only way to resolve my dilemma. Walking further and longer on this path of becoming a man, the road had narrowed. Ease and relaxation were distant points on an ever-receding horizon — one I could never reach.

It would only be many years later when I understood these dilemmas as part of living as a transsexual.

* * *

Changing genders has been a source of great spiritual inspiration, when I let it.

The narrowing of the path sometimes requires me to turn sideways and inch my way through, or step off the path into the brambles, or stop.

Of course I had no idea how to date women. Dating another lesbian as a lesbian differs from dating a woman as a man.

Now I know this. Then I didn’t. Little information existed for FtMs outside of a small forum on AOL and FtM International’s newsletter. FtMs weren’t keen to talk about this topic. Maybe we feared chatting about feelings of inadequacy or the losses of never having had a penis.

We talked instead about facial hair and the medical consequences of hormones on our bodies. We never discussed these in-between spaces — I like to call them interstitial — shot through with fear, confusion, and anxiety that have made up a lot of my transsexual life. I thought of manhood as a destination rather than a process. Any misstep on the way to my goal meant I was a failure rather seeing the missteps (if it’s even fair to call them that) as part of the ongoing, sometimes difficult, always beautiful process of being a female-to-male transsexual.

* * *

For reasons still unclear to me I changed my mind and continued taking my hormones. Maybe something as shallow as refusing to give up shaving my face drove me to keep injecting testosterone every two weeks. I can’t recollect any particular reason for continuing. I just did.

The acceptance of contradictions, dead ends, and false turns seems to be very much a part of living as a transsexual. I see that now.

But then, with the cudgel of the straight line from A to B, I beat myself up. It wasn’t even my body that drove me. It was some existential need to find fault with everything about my transition.

It wasn’t perfect. Nothing ever is.

Radical self-acceptance means living in the middle of a mess sometimes (maybe a lot of the time) while trying to keep a beginner’s mind about the process.

As I struggled with the decision to stop hormones, I remembered the excitement and pride I felt when I first began testosterone and the thrilling fantasies I had about dating women as a man. Of course these fantasies got tempered by the fear I saw in women’s eyes when they saw me as a man. Instead of banishing the fantasies, which I had been doing, I tried a different approach, one that included holding both truths inside of me.

Intimate terrorism and sexual assault make women fear men. But I am a different kind of man, one who understands that my penis is not a weapon.

* * *

Each step on this journey has asked me to make my circle of self-acceptance a little bit larger, to practice a kind of spiritual acceptance of the contradictions and conundrums living at the heart of FtM transsexuality.

Now I see wrinkles above my knees, reflecting my aging body.

Rubbing testosterone gel on my shoulders once a day thrills me, a feeling I’ve never experienced with injectables, probably because I hate needles. But still. How many people relish taking a daily prescription of anything?

Each major surgical change — top surgery, then bottom surgery — has altered my perceptions of myself in my body and myself in my gender. Last year I tweaked my hormone dosage with great result.

Now I find myself in the midst of another technological change: weight-bearing exercise. Now I have aged to a point where I must work to keep some mass on my muscles. Now I endeavor to complete ten full push ups and ten assisted pull ups. I fail, every day.

I keep trying and I keep taking hormones.

In 1996, no charts could point me in the direction of transsexual true north. I winged it, never revealing my ambivalence and fear.

I can know some things only as I go through them. Ambivalence shouldn’t surprise me. It frightened me then. Now it seems ordinary, a natural part of the transitioning process.

Today I take great joy in what my body, and my body on hormones, can do. My heart continues to beat, my lungs expand and contract.

My eyes scan the gym and what a wonderful thing it is that I am a man. Two decades since my first hormone dose, and I still get a thrill.

Now I’m glad I kept taking hormones even when I wanted to stop on that long-ago night on the freeway, glad one part of me refused to listen to another part of me. I’m glad to be me today, stumbling towards ecstasy and the profound gifts transitioning has given me: my life, my beloved, my words.

I’m glad to be in this body, this lovely transsexual body.

May 30, 2018

A Minimalist Guide to Gender – Transgender or Otherwise

A lot of words have been devoted to minimalism: minimizing your clothes, your books, your money, even your relationships. I decided to apply a minimalist approach to gender.

Why not, right? Transsexual and transgender people know how much junk we get handed at birth about sex and gender and sexual orientation and femininity and masculinity.

Even after twenty-plus years of living as a female to male transsexual, I still ball myself up with all kinds of crap questions. Questions about what is real masculinity. Which is kind of a lousy thing to do to myself, since in asking it I’m already assuming that I’m not a man, really.

I mean I get that many people don’t think I’m a man. But, really, why should I do it to myself? (Not nice, I know.)

Language plays a huge role in how I think about my gender and how people explain gender to me.

We possess certain body parts:

I have toes.

I have genitalia

I have hands

I have legs

But we, you and I, exist:

I am a man

I am human

I am gendered

Gender is something that exists or happens. But I don’t possess it, per se.

In my minimalist approach I tried this:

I have gender

I do gender

Which then led to my minimalist approach to gender:

Got gender?

How do you do your gender?

You bet. I do my gender pretty awesomely, too.

And all those mean things I say to myself – Oh a female to male transsexual – Hah! You aren’t a real man – that’s part of the doing of gender. For me.

Transcendence and acceptance live in the mean-spirited thoughts, too. I will always say nasty words to myself. The do the job of getting in the way of me being present in my body as I do my transsexuality for today.

And there you have it. A minimalist guide to gender: you have gender or you do gender or probably both.

May 29, 2018

Sohini Chakraborty – Dance for Empowering Revolution

Sohini Chakraborty has been helping sex-trafficking survivors using dance movement therapy (DMT) through the nonprofit Kolkata Sanved, an organization she founded in 2004. DMT allows enables survivors to recover from the trauma they have experienced through the medium of the body.

“I feel that any creative expression, not only dance, can bring big change. If you look at history, creativity is really, really powerful. It can change society’s attitude. It’s a tool for recovery, healing, self-expression and reintegration.” (Vital Voices)

Artists as Activists is part of an ongoing curiosity I pursue through my email newsletter, Making Art in a Time of Rage.

May 28, 2018

No One Talks About Murder Like They Talk About Transsexual Genitalia

October, 1971 John Berderka discharged two no. 4 bullets into David Allen Sennett’s neck and shoulder, murdering him almost instantly.

When I said I was coming out of stealth mode, did you expect me to reveal my past as a woman? Tell you I’ve not always lived as a man? Disclose I have a complicated body?

I’m sorry not sorry to disappoint you.

The secret I carry can’t be found in my initially female genitalia nor in the scars under my chest or the birth certificate I changed from F to M in 2004; but in the shattered bone fragments of my grandfather’s skull spattered around his still running car. He slid into the Chevrolet to attend to a birth and as he turned over the engine the man who swore he would get even for his estranged wife’s social visits with my grandfather fired his shotgun at my grandfather’s jaw and neck.

My mother requested a closed casket at the funeral.

§ § § § § § § §

The secret I want to share with you today carries no salacious undertones or overtones, imports no agendas about my attempts to deceive or mislead you, lifts no blanket off a body that is really just female, if I could only just admit it.

No.

What I want to disclose is that my grandfather was murdered. What I want to share is that I am a survivor of intimate terrorism. What I want to leak is that on some days being a transsexual is the least complicated thing about me.

I can explain my genitalia. But my grandfather’s murder? I’d rather discuss my private parts as publicly as possible.

§ § § § § § § §

Publicly we treat murder like a common thief, worthy of attention only when the scale of the pilfering or violence exceeds our expectations. Think Bernie Madoff or Adam Lanza. Many people must be affected before the publicity machine churns into overdrive.

But let one lone macho man – preferably a former sports star or ex-military man – change his gender and the publicity machine churns into overdrive.

Family members left to live in the aftermath of unspeakable violation receive little attention from the media, and family members of perpetrators even less.

We act as though murder doesn’t exist; we act as though changing genders the far more compelling behavior than murder or surviving murder or what ever it is I’ve lived through; we act as though not talking about murder will protect us from it.

But you want to know about my secrets.

My secrets are many. I am ashamed that my grandfather is, and thus I am, a victim of domestic violence. The man who murdered my grandfather had vowed to murder his wife, my grandfather’s girlfriend. He skulked around her apartment building waiting. When my grandfather left to drive to the hospital, he changed his mind and killed my grandfather instead.

I hate this man and would gladly throttle him myself, or better yet, crush his skull with a baseball bat. I wish to make him suffer, and greatly. In the middle-class language of my peers, this makes me a not-very-nice person.

Entre nous: I have no fucks to give on this point.

I laugh at people who seem bewildered or shocked about violence in the world. Really, I want to say. How stupidly naive are you to evil in the world. Men – and it’s always mostly men, isn’t it – murder and pillage, for nationalist reasons and familial ones, yes, but because of insecurity, rage and because they can.

Wanting to slaughter this now senile old man makes me part of the problem. I can’t seem to be part of the solution, unless that includes his death.

Another secret: my transsexuality, talking about it, sharing it, especially to nontrans/cisgendered people bores me. I know my transsexual body makes me the most interesting man in the room, to you. For me it is now like dandelions in the spring. Common and everyday.

I can never seem to find the words to discuss my grandfather’s murder. It’s as though the surfeit of words required of my transsexuality creates an equal lack of words about his murder, even though I can discuss easily murdering the murder.

But the hole, the void, the absence, the thing that happened to me and my brother and my mother and to my grandfather’s community and to the murderer’s son and daughter and estranged wife, that keeps happening, at least for me. Of this, what can I say?

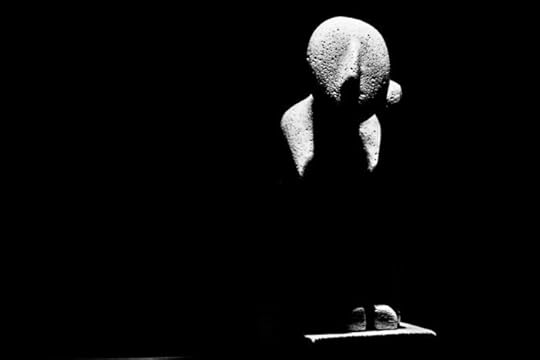

The act creates a black hole like the one the physicist’s describe. The force of its pull sucks in all matter and light at its edge.

Get too close and I’ll disappear. This is another secret I harbor: in my silence I collude with the murderer.

But here, let’s talk about my genitalia or how duped you think my wife is. We both want to. You, because you love salacious, voyeuristic gossip, and me, to avoid the void.

A confidence: when left to draw on my own as a child I would often sketch bloodied stick figures in black, crying red tears underneath a rifle-filled sky.

And another: I am a murderer. When we would visit the woman my grandfather loved, the one he left on the night of his murder, I would reenact my grandfather’s slaughter thinking, mistakenly, that his murder had occurred outside the house she lived in then. Pressing myself against a cliff of furrowed dirt, I waited for the opportune time to rush any car sitting in the driveway. Pow! Pow! Pow! My Mannix-style handgun sounded out its report in my head.

Never once did I imagine myself as my grandfather. Kill or be killed, that’s what a murderer thinks, I guess. Kill or be killed, that’s what a child – even a transsexual child – learns in the aftermath of a family murder.

Or maybe that’s how it is for men. I hadn’t realized how violent men are to other men until I began living full time as a man. In the early years the femininity I thought I had shed reappeared – or maybe, more truthfully – transformed me into a thin, gay looking white man.

Hey faggot! I’m going to kill you!

The menacing glare of the taut, compact white man in the work lunch room.

I will rape you.

I know you will, I wanted to say to him.

A secret: I felt intense self-hatred at my fear towards this man. My inability to defend myself against him gave me pause and made me question my decision to transition.

Another secret: now I know to fight back. How to bully men verbally, condescend towards them if they are working-class or poor. Kill or be killed. I will be the only walking away from this encounter.

This disclosure reddens my face with shame.

You want to hear about how becoming a man is all about privilege and getting to the top of the food chain.

But do you want to hear about my grandfather? Or the child who could only transform the violence of intimate terrorism by becoming the aggressor?

Or that I’ve raged in ways that have terrified people I love?

Or that I think anyone who asks about my genitalia lacks imagination and dignity?

I’ll show you mine, if you show me yours.

If I do decide to show you mine, I need you to understand that I control that narrative; that I get to say whatever I want; that you will have to listen until I am finished. The over-verbalization of my transsexuality, and the under-verbalization of my grandfather’s murder are two sides of the coin. So be prepared to have me expose in public something far deeper and more tender than my privates: anguish, rage and grief.

May 25, 2018

Call Me Enraged: Simplistic Transsexual Metaphors

Doctors are unsure if transsexuals suffer from a disease of the soul or one of the brain, and so they cover their bases and create a diagnostic box, a square of the soul that must be ticked before a surgeon can remediate our malfunctioning bodies.

In lay terms, we say we are either:

born this way; or

born in the wrong body.

We are “born this way” means we have a compelling psychiatric disorder, found in the DSM, and called gender dysphoria.

We are “born in the wrong body,” possibly as a result of something that happened in utero, is a fact that can be remedied through surgeries, the path through which our psychiatric disorder — our very soul — may be relieved.

Both descriptions speak to a possible malaise of the soul and the brain. Both spring from narratives derived from the psychiatric and medical communities.

Both locate the source of our dysphoria within us as individuals.

Both argue transsexuality is a problem to be fixed.

Both believe the body is the enemy.

Both are institutional and hackneyed.

The Problem

Indeed, my soul and my brain were relieved through surgeries. Without them I imagine an alternative future wherein I committed suicide, as my dysphoria felt that profound and overwhelming. The cutting effects of my dysphoria got fixed by many good and fine doctors.

These same doctors, though, have a habituated need to answer Why. The answer to Why, in order to receive the surgeries I needed to live my life, cost money — a lot of it. The peddlers of the Why — Big Insurance — use diagnostic categories as the medium through which they will release money from their cheap, bony grasp.

The accounting of Why seems simple. Big Insurance traffics in ICD-10 codes for any condition. Transsexuality is a mental condition. No physical tests — no blood tests, no radiographs, nor minor exploratory surgeries — exist to diagnose transsexualism, a wholly and purely mental condition.

Mental conditions are the purview of soul doctors; and as gatekeepers between me and Big Insurance, soul doctors conducted interviews, administered testing instruments like the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, scheduled more interviews with my beloved, then determined if my tests — and I use this word shorn of all scientific weight — indicated I am a transsexual.

My declaration, my self-report of severe gender dysphoria, was immediately voided. They declared me an Unreliable Witness. I used to become enraged even thinking about this truth.

The answer to Why could never be because I want to. Even if I were willing and able to pay for my own surgeries, without a tidy, psychologically categorized answer to Why, my hometown surgeons would refuse. I could have used an out-of-town surgeon, flying out-of-state, recovering in a hotel room. This option terrified me, as I feared a hypothetical visit to an emergency room without immediate (or near immediate) access to my primary care physician.

For years I resented all of them for wasting my time. Now I know that neither they nor I live in a time in which I can change my body on demand. So what, exactly, is my problem?

Tidy and Categorized

These two explanations allow ordinary citizens, people lacking doctoral degrees in clinical psychology or medical degrees of any kind, to put me in the diagnostic box, label it, tidy and categorized, just like Big Insurance, and keep me there.

Forever.

These two short phrases reflect the total of most people’s ability, even willingness, to understand my experiences as a transsexual. Nontranssexuals that they are, the sides of the box they erect around me shape their sense of roomy normalcy, and of the freedom surrounding them.

Me? I’m hemmed in on all sides, squished into one neat box, squared. Prearranged living conditions don’t suit me, especially ones where I’m required to sort through my life, storing all the messy, contradictory and odd episodes into an offsite storage facility.

Don’t ask me to dump the stuff of my life into some little, shitty tiny bin you’re comfortable in. Box yourself in. The narrative that people want me to use is one in which I have had no input.

Think of this diagnostic box, with its everyday usages, as akin to arriving at a friend’s party. Once there, you realize they’ve set you up on a surprise date with a nice, well-meaning person who already thinks they know everything about you, exhibiting utter disinterest in your opinion about your own life. Your experience has nothing to do with their understanding. It doesn’t interest them one bit.

Distasteful Options

When confronted with people who believe they support me but who grow deadly bored if disrupted from their plan to discuss me in an authoritative but dismissive manner, what should I do?

If I have no desire to waste my time and energy forcing my opinion on someone who wills it away with distracted looks, how should I respond?

I can choose silence, refusing to participate in a conversation with anyone exhibiting no interest in me. But I fear my quiet would signal tacit agreement with these metaphors.

I can attempt to counter those narratives with my own. But then I act as though I disagree with the speaker’s support.

“No, I wasn’t born in the wrong body,” I say as I begin to watch their eyes glaze over.

“My choices result from complex interactions,” and as I continue, the other person may very well begin withdrawing their support.

“Gosh! I was just trying to be supportive and now you’re so triggered!”

My Naming Attempt — A Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery

When I transitioned in the 1990s, I believed I was born in the wrong body, and hated my body and myself for it. This is by far the worst choice I could have adopted when confronted with these metaphors. The richness of my relationship to my body withered, if it had any chance to grow at all. Neither nuance nor complexity of feeling flourished in that acidic environment.

As I transitioned I felt I had to lie to psychological and medical experts regarding any feelings of fear, concern, or ambivalence. If I revealed any anxiety about transition, about assuming male privilege, or about fears of homophobic violence, I believed there was a strong possibility of losing access to hormones. Since I was born in the wrong body, the thinking went, how could I possibly be anxious about becoming a man? The hormones and surgeries were simply going to fix the problem.

In late 2003, I had breast reduction surgery. A cup and a half too large for the keyhole procedure, I needed a full-blown reduction, a more difficult procedure, requiring the surgeon to remove breast fat and breast tissue along the muscle, with the hope that the scarring would reside along the pectoralis major line, underneath the ridge created by superior chest muscles.

To remove the necessary breast tissue, doctors cut off my nipples, extracted the tissue, stitched up the sutures, and regrafted the nipples. These two little mounds of tissue no longer have any erotic sensation.

In the ledger of transsexual accounting, the credit for becoming a man required an opposing debit of erotic sensation.

I’m not bitter. I hated my breasts and am glad they are gone, but I still miss erotic sensation, and understand now how much my transsexual experiences are ones of intertwining loss and joy.

This kind of complexity can’t get started in the born this way/broken body narrative.

Transsexuality is an ongoing series of conundrums and contradictions. A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

I fail to explain it every time I attempt it.

At the twilight of each day, I’ve aged a little more. Am I a man? A madwoman? A man with the body of a woman? An FtM? An MtM? The wrong body metaphor reduces all these possible truths to none. A single stinking story written by hacks utterly without imagination.

The body itself, wrote Walt Whitman, balks account.

If being born in the wrong body is the answer, what is the question?

I, and we, deserve so much more than these metaphors. All of us can count past zero.

This essay appears in Moxie, Vol. 1.

May 23, 2018

Be Daring: Love the Body You Have, Not the One You Want

I have uttered this mantra countless times since I transitioned from female to male more than twenty years ago. Nothing prepared me for the degree of self-loathing I would feel post transition. Pre-transition disgust seemed understandable. But after the hormones took effect and I obtained my court ordered name change and legally altered all my important documents, I should still hate myself and my body?

I have uttered this mantra countless times since I transitioned from female to male more than twenty years ago. Nothing prepared me for the degree of self-loathing I would feel post transition. Pre-transition disgust seemed understandable. But after the hormones took effect and I obtained my court ordered name change and legally altered all my important documents, I should still hate myself and my body?

Call me surprised, to say the least. Hormones should have provided the salvation I sought. But they didn’t, and I felt like a failure, alone. My body had failed me, again. Happiness could be found in costly surgeries with sometimes poor outcomes. Yes, I would have a something like a penis but I would also have multiple revisions and permanent scarring at the sight where doctors harvested tissue for the graft. The cost made me balk, too.

Even with a phalloplasty I would have felt like a failure and an imposter. My genitalia would have still been wrong. Without too much effort I decided to forego surgery. It wasn’t right for me. Others have made that choice, and I congratulate them heartily for doing what they believe best for their bodies.

Sans phalloplasty I faced an ongoing confrontation with a very wrong body. I wanted to have sex with women, in particular ways, ways that seemed impossible without a penis. Dildos helped. There was always a moment, though, when everything stopped to put on the strap, cinch it up, adjust, re-cinch, that just killed my sexy mood. I became a novice actor in my first audition, sweating under the lights, forgetting my lines, laughed at by people sitting in the darkened seats.

I made a confession, of sorts, of my shame. Nothing direct but my words contained enough detail for my friend, a high-femme, sex worker, to smile at me.

“Are you kidding me? What you have is so sexy. Think about it. You’re a man with a hard-on that never fails. Ever.”

“Love the body you have. Not the one you want.” A life-saving incantation, one I’ve repeated so often I’ve come to believe it. Learning to work with what I have — to see my “loss” as a “win” since I really do have a hard-on that never fails, ever — has been an ongoing gift I give myself, some days a dozen times or more. I must. The alternatives feel too bleak and depressing, always chasing a perfect body, a body existing only in my mind, a dangerous place, best visited with other people.

Through these same people I have found redemption. My lover, of course. She has loved me with a steadfast ardor that still takes my breath away. Friends, too, in their own ways reflect back to me a vision of myself I find attractive and one I can live with everyday. Whether they think about it or not, they love the body I have. So why shouldn’t I?

The work of greater bodily acceptance has gotten easier as I have grown older. At 53, having been on hormones for more than two decades, I can honestly say that, should anything heartbreaking befall my lover, I could, one day, date again. Date with confidence and joie de vivre. But what’s cool now is that I bring this self-acceptance to my love today.

I don’t need to wait to express my self-acceptance. Tomorrow may never come and now seems as a good a time as any to share my sense of self-sexiness. The world needs more of this kind of work to be done. Self-sexiness defies age, race, class, ability and any other junk tossed our way.

The pursuit of greater self-acceptance has taught me that most of us hate our bodies. Why wouldn’t we? Too fat or too thin, too dark or too swarthy, we labor under definitions of beauty — only skin deep and narrowly defined — designed to make us feel like we have no right to live.

Revolutions, I’ve also learned, actually begin in the mirror. I might effect a change of government or social policy through collective action. When I do this work hating my body, sloth and gluttony wait for me at home and in my bed. Envy consumes me. Monsters stare back at me from the mirror.

Love the body I have, not the one I want. No greater work exists.

This piece first appeared at onescene.