Nancy Butts's Blog, page 2

February 27, 2015

Power Can Go To Your Head: The Perils of Omniscient POV

Note: This is the fifth in a series of articles on demystifying viewpoint. The originals will appear first as posts on my Spontaneous Combustion blog, then be archived on my website as downloadable PDFs.

Library of CongressSome of my favorite books are written in omniscient viewpoint—and yet omni POV is my least favorite form of narration. It makes even the most modern of books sound antique—and don't even get me started on the almost ubiquitous head hopping to be found in novels with omniscient narration. I am convinced that such head hopping is the leading cause of vertigo among avid readers. Seriously. The National Institutes of Health should do a study.

Library of CongressSome of my favorite books are written in omniscient viewpoint—and yet omni POV is my least favorite form of narration. It makes even the most modern of books sound antique—and don't even get me started on the almost ubiquitous head hopping to be found in novels with omniscient narration. I am convinced that such head hopping is the leading cause of vertigo among avid readers. Seriously. The National Institutes of Health should do a study.

OK, let me remove my tongue from my cheek for a moment. If you have read the earlier installments of this web series on viewpoint, you will already know that I am just a teensy bit prejudiced in favor of single viewpoint. I'm not all that fond of shifting or multiple POV; and I have just made it obnoxiously clear that omni POV, as I will call it for short, is also a member of my Hall of Shame.

That being said, I adore books like Harry Potter and Lemony Snicket—both of which make use of omniscient narration. And I'm not just pinching my nose, holding my breath, and vowing to "get through it" when I read these books either. I actually enjoy what these two gifted storytellers are able to accomplish with their skillful use of omniscient viewpoint.

So what separates good from bad when it comes to omni POV? And why do I think that it is a very dangerous form of narration, especially for new writers?

Before I talk about that, let me back up and make sure it is clear exactly what omniscient viewpoint is. It comes in several different flavors, the distinctions between which can get fairly subtle. In the book The Power of POV which I have recommended multiple times in this web series, Alicia Rasley divides omniscient narration into three basic kinds: objective, classical omniscient, and contemporary omniscient.

For the purposes of this piece, however, I don't think it's useful to delve too deeply into the distinctions between them. If you're interested, read Rasley's book [which I think you should do anyway].

For the purposes of this piece, however, I don't think it's useful to delve too deeply into the distinctions between them. If you're interested, read Rasley's book [which I think you should do anyway].

I think the most helpful way to look at omniscient narration is simply to think of it as another kind of third person. We are already familiar with limited third person, where a book is written using he/she but the perspective remains inside the mind of one or more of the characters.

Well, in omniscient narration you are for the most part outside the viewpoint of any of the characters. Thus you can think of omni POV as a distant or impersonal form of third person rather than a personal one; or an exterior form of third person rather than an interior one.

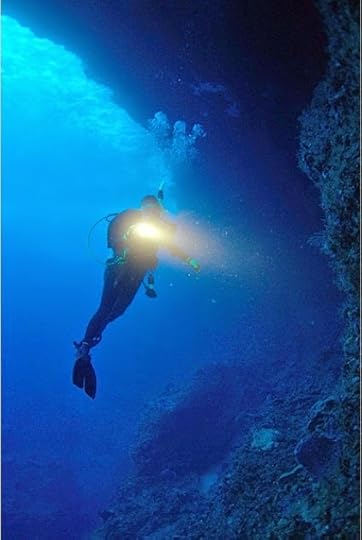

Photo by Steve WilsonWhatever it is called, when you write in omniscient narration you are not limited by anything any of the characters know—hence the name omniscient, which means all-knowing. Omni POV is a good way to let readers in on information that you don't want your hero to know just yet. For example, if your main character is trying to sneak up on the lair of the villain, you can increase the tension and suspense for readers by letting them know about the evil minions lurking in the shadows, while at the same time keeping the hapless hero in the dark about the danger that awaits him. " Three men with guns stood as still as statues on the other side of the door whose lock Archie had just successfully picked."

Photo by Steve WilsonWhatever it is called, when you write in omniscient narration you are not limited by anything any of the characters know—hence the name omniscient, which means all-knowing. Omni POV is a good way to let readers in on information that you don't want your hero to know just yet. For example, if your main character is trying to sneak up on the lair of the villain, you can increase the tension and suspense for readers by letting them know about the evil minions lurking in the shadows, while at the same time keeping the hapless hero in the dark about the danger that awaits him. " Three men with guns stood as still as statues on the other side of the door whose lock Archie had just successfully picked."

Omniscient narration is also handy in certain genres, such as fantasy, science fiction, and sweeping historical sagas. Here a writer can use omni POV to do two things. First, the all-knowing author can use her omniscience to fill readers in on necessary history or backstory that again, no one character might know.

Second, if it's important to the book for the author to keep track of how multiple characters are affected by something like a war , natural catastrophe, man-made apocalypse, or epic quest, omniscient narration is a smoother, more seamless way to do that than a frequently-shifting multiple POV. [Which can end up feeling like a game of musical chairs; when the chapter stops, readers wonder, which character's chair do I have to scramble to sit in next?]

But in a touch of dramatic irony that fiction writers can appreciate, it is the very strengths of omni POV which can lead to its doom. The all-knowing writer's ability to expound at length on absolutely any character's backstory, any event's history, any fantasy world's provenance, or any sci-fi gadget's fascinating inner technology can all too quickly lead to the dreaded "information dump." That's what it's called when a writer allows the characters to go into hibernation and the plot to stall out while she goes on and on for pages of exposition, in what amounts to a term paper within the novel. Boring!

And if you're not careful, omniscient narration can lead you to reveal too much, too soon—which can ruin a good thriller, ghost story, or mystery.

I also think that omniscient narration can sound old-fashioned to today's readers, since many of the classics that we grew up on—or were forced to read by our English teachers at school—were written in omniscient narration. So even if a book was published in the 21st century, if it is written in omniscient POV, we feel a sort of literary déja vu when we read it—a flashback that makes the modern story feel as if it were a relic from the 19th century.

But to me the number one failing, the Fatal Flaw, of omniscient narration, is its impersonality. Readers don't know who it is that is dispensing this encyclopedia of information. Is it some god-like narrator, or is it the author? If it's the latter, is he or she wearing an invisibility cloak that we're supposed to pretend not to see, or is this some kind of purposeful meta-fictional insertion of the writer's persona into the book?

Zeus

Zeus

Photo by Marie-Lan NguyenOr is the narrator an eerily amorphous no one at all? That's the hallmark of what Rasley calls objective or camera's-eye POV.

And not only are readers unsure of who the narrator is in omniscient viewpoint, and what their relationship to that narrator is supposed to be, they also aren't given the opportunity to get know any of the characters all that well. As a consequence, readers may never bond with any character. That emotional distance heightens the risk of alienating readers from the book all together, to the point that they put it down for good.

Writers who use omniscient POV know this, which is perhaps why you see a lot of what is called "dipping," or momentarily slipping into the viewpoint of one of the book's characters. JK Rowling is a genius at this. The first chapter of Goblet of Fire is a superb example of how to write omniscient narration well.

Midway through the chapter, Rowling makes the graceful narrative glissade that is called dipping. Within the space of one paragraph, she descends gradually from the stratospheric heights of omniscience. First she slips into the heads of several nameless village boys, all at once, in a kind of joint or communal POV, telling us that they teased the crippled old gardener Frank Bryce simply for the cruel fun of it.

Then, in the very next sentence, Rowling descends even further. This times she dips into Frank's head to tell us that Frank has misinterpreted the boys' motives. He believes that they torment him because they blame him for the murders of Tom Riddle and his family—though we already know that those murders bear the unmistakeable stamp of dark magic.

The fact that Rowling changes POV twice in one paragraph could mark this as head hopping—the worst of the writer's Deadly Sins. Indeed, it can be difficult to know when a writer has transgressed, crossing the line from dipping to head hopping, and I am probably a harsher judge of that than most. Nonetheless, I think Rowling avoids being branded with head hopping here primarily because for the rest of the chapter, she stays in Frank's head. If she had jumped back out of Frank's head again, that would have been head hopping.

But it's a narrow escape, and that's my point; it's devilishly difficult to avoid head hopping when you write in omniscient narration and try to dip. Harsh judge that I am, I think that author Trenton Lee Stewart made that mistake in his best-selling middle grade novel The Mysterious Benedict Society.

Stewart uses omniscient narration throughout the book, though he frequently dips into several of the characters' viewpoints. Most of the time, he stays in a POV long enough to avoid head hopping—but not always. Look at this passage where the adult mentor is telling the four young characters about a challenging task ahead. One of them gets a little nervous and needs a bathroom break.

Stewart uses omniscient narration throughout the book, though he frequently dips into several of the characters' viewpoints. Most of the time, he stays in a POV long enough to avoid head hopping—but not always. Look at this passage where the adult mentor is telling the four young characters about a challenging task ahead. One of them gets a little nervous and needs a bathroom break.

To me, going into a character's head for just one sentence, and for no compelling plot purpose, is head hopping. So with apologies to Mr. Stewart, I do believe that's what he's done here.

The point is, if a talented and experienced author can make that kind of slip-up, what hope do the rest of us have of avoiding the same trap? It is just too perilously easy to go astray with omniscient POV.

So proceed at your own risk. If you are writing the kind of book that might benefit from the peculiar powers of omniscient viewpoint, then go for it! Just keep your wits about you at all times, and stay on the lookout for the pitfalls that await the unwary writer with this form of POV.

[© 2015 This article is subject to copyright. Please do not use or reproduce without express written permission from the author.]

Next—Which POV technique is best for you?

Library of CongressSome of my favorite books are written in omniscient viewpoint—and yet omni POV is my least favorite form of narration. It makes even the most modern of books sound antique—and don't even get me started on the almost ubiquitous head hopping to be found in novels with omniscient narration. I am convinced that such head hopping is the leading cause of vertigo among avid readers. Seriously. The National Institutes of Health should do a study.

Library of CongressSome of my favorite books are written in omniscient viewpoint—and yet omni POV is my least favorite form of narration. It makes even the most modern of books sound antique—and don't even get me started on the almost ubiquitous head hopping to be found in novels with omniscient narration. I am convinced that such head hopping is the leading cause of vertigo among avid readers. Seriously. The National Institutes of Health should do a study.OK, let me remove my tongue from my cheek for a moment. If you have read the earlier installments of this web series on viewpoint, you will already know that I am just a teensy bit prejudiced in favor of single viewpoint. I'm not all that fond of shifting or multiple POV; and I have just made it obnoxiously clear that omni POV, as I will call it for short, is also a member of my Hall of Shame.

That being said, I adore books like Harry Potter and Lemony Snicket—both of which make use of omniscient narration. And I'm not just pinching my nose, holding my breath, and vowing to "get through it" when I read these books either. I actually enjoy what these two gifted storytellers are able to accomplish with their skillful use of omniscient viewpoint.

So what separates good from bad when it comes to omni POV? And why do I think that it is a very dangerous form of narration, especially for new writers?

Before I talk about that, let me back up and make sure it is clear exactly what omniscient viewpoint is. It comes in several different flavors, the distinctions between which can get fairly subtle. In the book The Power of POV which I have recommended multiple times in this web series, Alicia Rasley divides omniscient narration into three basic kinds: objective, classical omniscient, and contemporary omniscient.

For the purposes of this piece, however, I don't think it's useful to delve too deeply into the distinctions between them. If you're interested, read Rasley's book [which I think you should do anyway].

For the purposes of this piece, however, I don't think it's useful to delve too deeply into the distinctions between them. If you're interested, read Rasley's book [which I think you should do anyway].I think the most helpful way to look at omniscient narration is simply to think of it as another kind of third person. We are already familiar with limited third person, where a book is written using he/she but the perspective remains inside the mind of one or more of the characters.

Well, in omniscient narration you are for the most part outside the viewpoint of any of the characters. Thus you can think of omni POV as a distant or impersonal form of third person rather than a personal one; or an exterior form of third person rather than an interior one.

Photo by Steve WilsonWhatever it is called, when you write in omniscient narration you are not limited by anything any of the characters know—hence the name omniscient, which means all-knowing. Omni POV is a good way to let readers in on information that you don't want your hero to know just yet. For example, if your main character is trying to sneak up on the lair of the villain, you can increase the tension and suspense for readers by letting them know about the evil minions lurking in the shadows, while at the same time keeping the hapless hero in the dark about the danger that awaits him. " Three men with guns stood as still as statues on the other side of the door whose lock Archie had just successfully picked."

Photo by Steve WilsonWhatever it is called, when you write in omniscient narration you are not limited by anything any of the characters know—hence the name omniscient, which means all-knowing. Omni POV is a good way to let readers in on information that you don't want your hero to know just yet. For example, if your main character is trying to sneak up on the lair of the villain, you can increase the tension and suspense for readers by letting them know about the evil minions lurking in the shadows, while at the same time keeping the hapless hero in the dark about the danger that awaits him. " Three men with guns stood as still as statues on the other side of the door whose lock Archie had just successfully picked."Omniscient narration is also handy in certain genres, such as fantasy, science fiction, and sweeping historical sagas. Here a writer can use omni POV to do two things. First, the all-knowing author can use her omniscience to fill readers in on necessary history or backstory that again, no one character might know.

Second, if it's important to the book for the author to keep track of how multiple characters are affected by something like a war , natural catastrophe, man-made apocalypse, or epic quest, omniscient narration is a smoother, more seamless way to do that than a frequently-shifting multiple POV. [Which can end up feeling like a game of musical chairs; when the chapter stops, readers wonder, which character's chair do I have to scramble to sit in next?]

But in a touch of dramatic irony that fiction writers can appreciate, it is the very strengths of omni POV which can lead to its doom. The all-knowing writer's ability to expound at length on absolutely any character's backstory, any event's history, any fantasy world's provenance, or any sci-fi gadget's fascinating inner technology can all too quickly lead to the dreaded "information dump." That's what it's called when a writer allows the characters to go into hibernation and the plot to stall out while she goes on and on for pages of exposition, in what amounts to a term paper within the novel. Boring!

And if you're not careful, omniscient narration can lead you to reveal too much, too soon—which can ruin a good thriller, ghost story, or mystery.

I also think that omniscient narration can sound old-fashioned to today's readers, since many of the classics that we grew up on—or were forced to read by our English teachers at school—were written in omniscient narration. So even if a book was published in the 21st century, if it is written in omniscient POV, we feel a sort of literary déja vu when we read it—a flashback that makes the modern story feel as if it were a relic from the 19th century.

But to me the number one failing, the Fatal Flaw, of omniscient narration, is its impersonality. Readers don't know who it is that is dispensing this encyclopedia of information. Is it some god-like narrator, or is it the author? If it's the latter, is he or she wearing an invisibility cloak that we're supposed to pretend not to see, or is this some kind of purposeful meta-fictional insertion of the writer's persona into the book?

Zeus

ZeusPhoto by Marie-Lan NguyenOr is the narrator an eerily amorphous no one at all? That's the hallmark of what Rasley calls objective or camera's-eye POV.

And not only are readers unsure of who the narrator is in omniscient viewpoint, and what their relationship to that narrator is supposed to be, they also aren't given the opportunity to get know any of the characters all that well. As a consequence, readers may never bond with any character. That emotional distance heightens the risk of alienating readers from the book all together, to the point that they put it down for good.

Writers who use omniscient POV know this, which is perhaps why you see a lot of what is called "dipping," or momentarily slipping into the viewpoint of one of the book's characters. JK Rowling is a genius at this. The first chapter of Goblet of Fire is a superb example of how to write omniscient narration well.

Midway through the chapter, Rowling makes the graceful narrative glissade that is called dipping. Within the space of one paragraph, she descends gradually from the stratospheric heights of omniscience. First she slips into the heads of several nameless village boys, all at once, in a kind of joint or communal POV, telling us that they teased the crippled old gardener Frank Bryce simply for the cruel fun of it.

Then, in the very next sentence, Rowling descends even further. This times she dips into Frank's head to tell us that Frank has misinterpreted the boys' motives. He believes that they torment him because they blame him for the murders of Tom Riddle and his family—though we already know that those murders bear the unmistakeable stamp of dark magic.

The fact that Rowling changes POV twice in one paragraph could mark this as head hopping—the worst of the writer's Deadly Sins. Indeed, it can be difficult to know when a writer has transgressed, crossing the line from dipping to head hopping, and I am probably a harsher judge of that than most. Nonetheless, I think Rowling avoids being branded with head hopping here primarily because for the rest of the chapter, she stays in Frank's head. If she had jumped back out of Frank's head again, that would have been head hopping.

But it's a narrow escape, and that's my point; it's devilishly difficult to avoid head hopping when you write in omniscient narration and try to dip. Harsh judge that I am, I think that author Trenton Lee Stewart made that mistake in his best-selling middle grade novel The Mysterious Benedict Society.

Stewart uses omniscient narration throughout the book, though he frequently dips into several of the characters' viewpoints. Most of the time, he stays in a POV long enough to avoid head hopping—but not always. Look at this passage where the adult mentor is telling the four young characters about a challenging task ahead. One of them gets a little nervous and needs a bathroom break.

Stewart uses omniscient narration throughout the book, though he frequently dips into several of the characters' viewpoints. Most of the time, he stays in a POV long enough to avoid head hopping—but not always. Look at this passage where the adult mentor is telling the four young characters about a challenging task ahead. One of them gets a little nervous and needs a bathroom break....and then Mr. Benedict added, “Now, do you truly need to use the bathroom, or can you wait a few minutes longer?” [Omni POV]

Sticky truly did, but he said, “I can wait.” [Sticky's POV]

“Very well...” Mr. Benedict said [Omni POV]

To me, going into a character's head for just one sentence, and for no compelling plot purpose, is head hopping. So with apologies to Mr. Stewart, I do believe that's what he's done here.

The point is, if a talented and experienced author can make that kind of slip-up, what hope do the rest of us have of avoiding the same trap? It is just too perilously easy to go astray with omniscient POV.

So proceed at your own risk. If you are writing the kind of book that might benefit from the peculiar powers of omniscient viewpoint, then go for it! Just keep your wits about you at all times, and stay on the lookout for the pitfalls that await the unwary writer with this form of POV.

[© 2015 This article is subject to copyright. Please do not use or reproduce without express written permission from the author.]

Next—Which POV technique is best for you?

Published on February 27, 2015 11:23

February 1, 2015

Priming the pump: my home-brewed writing practice

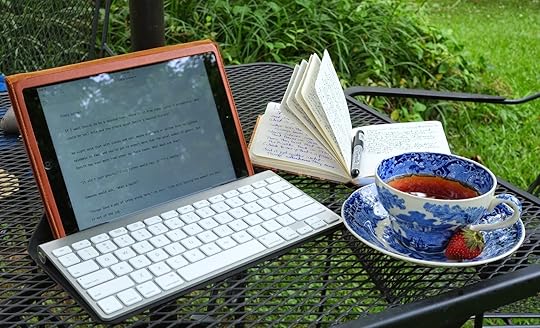

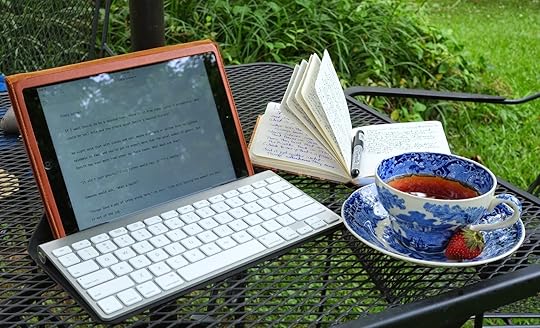

Photo by ProjectManhattanAfter lamenting the failure of my morning page experiment last week, I vowed to cook up a little something of my own to try instead. No way I was going to give up entirely on my search for a method that would help me get back on track in terms of my writing.

Photo by ProjectManhattanAfter lamenting the failure of my morning page experiment last week, I vowed to cook up a little something of my own to try instead. No way I was going to give up entirely on my search for a method that would help me get back on track in terms of my writing.What I wanted was some regular discipline that would do more than help me be creative in a general sense—which is what Julia Cameron’s morning pages are designed to do.

I also wanted something more than a technique to merely get me started—to get me past that brain-petrifying paralysis that afflicts many of us when we first sit down and try to begin a work session. Giving one a “jump start” like this is what Natalie Goldberg’s freewriting exercise is designed to do.

No, I wanted a more laser-like focus on productivity: on having something useable and at least halfway decent to show for my sweat and tears at the end of the day.

And I did come up with something—although I can’t claim that it is original or unique. Other writers and teachers before me have devised a modification of freewriting, one that gives it more structure by targeting a specific topic or goal for each session.

Once you do that, however, can you call it freewriting anymore? So I’m not naming my “method” that, if you can dignify what I’m doing with that formal a designation. I call it Priming the Pump . It’s simple, but in the first week that I’ve tried it, it’s accomplished just what I hoped it would—it has helped me produce something tangible at the end of each work day, something that moves my work forward in a measurable and substantive way. I’m quietly ecstatic about the results so far.

This method requires that you have a writing project already underway. This is not a brainstorming technique, though I suppose you could use it for that as well. There are five steps to Priming the Pump .

Do a Preliminary Review of a work in progressWrite down a Question of the DaySpend either a period of time [ten to fifteen minutes?] or a number of words [100 to 700?] sketching out Starting Notes about the questionSeamlessly Shift into Writing actual sentences, paragraphs, and [hopefully] pagesDo a Summary Review of work done. At the end of the session, write down the answer to the initial question, to see what tangible progress you’ve madeI’ve used this five-step practice this week to help claw my way out of an uncharted swamp in the middle of a middle grade novel. I had lots of plot ideas swirling around my head, but they were confusing and contradictory and unclear. After writing the first ten chapters and being stalled for ages, I needed to blow away the fog by figuring out precisely what happens in the remaining chapters of the book. Yes, this means a dreaded outline, which I don’t always use but which I have come to think I desperately need on this particular book.

Photo by Yann Richard (Ze)

Photo by Yann Richard (Ze)The first thing I did was briefly glance over what I had already written of the book, and the notes I’d made for what was to come: Step 1, the Preliminary Review.

From that a clear Question of the Day arose, almost asking itself: Step 2. I wrote it down on a sticky note [an electronic one] and left it floating on the screen of my laptop where it would always be visible. You could do the same thing by using a paper Post-It note, an index card, or by simply jotting down the question at the top of the page on which you’re about to write.

It’s important to be as specific as you can when framing your question, because that specificity will help steer you in a fruitful direction. If you simply ask yourself, “What happens next?” your mind may seem even emptier of words and ideas than before. But if you ask, “What happens after the Hero finds the treasure map but before he meets the nefarious guide?” you will have a much better chance of finding the answer during your daily writing session.

Photo by JaypeeI think it is also important to write down the question in twenty-words or less, and to keep it somewhere that is always visible during your writing session. Then if you start to feel lost again, you have only to glance up to find your writing “compass” right there to steer you back onto the path.

Photo by JaypeeI think it is also important to write down the question in twenty-words or less, and to keep it somewhere that is always visible during your writing session. Then if you start to feel lost again, you have only to glance up to find your writing “compass” right there to steer you back onto the path. In Step 3, I don’t think it matters whether you have a time goal for your Starting Notes, or a word goal. Do whatever works best for you. I can dash off 700 words in about 15 minutes, if I’m writing on my Macbook Air or iPad, so 700 words was the goal I set for myself.

But in practice, I found I got so quickly immersed in puzzling out the answer to my question that the goal disappeared. I would look up an hour or so later and realize I had burned up those 700 words a long time ago, and was already well into Step 4: Shift into Writing.

Work as long as you can—whether that means as long as you continue to produce useful work; as long as your poor stiff joints hold out; or as long as your dog, cat, family, or boss at your day job will let you.

I do think it’s important to know when to stop. This is going to vary with every person; we all seem to have only so many hours of good writing in us each day before the juices stop flowing. Pull the plug when you realize that are doing more harm than good by continuing to write: either producing drivel, haring off on a wild detour, or bogging down in a quagmire of confusion or needless complexity.

But before you leap up from your desk and race off to celebrate with a glass of wine, don’t forget Step 5: the Summary Review. Briefly read back over what you’ve written during the session, and write down the answer to your Question of the Day. Don’t skip this step, as I’ve found it helps keep you on target—and often leads to the question you’ll work on the next day. This week while I was experimenting with it, the next day’s question often arose spontaneously while I was writing, which was an unexpected gift.

Writing down the answer to your daily question also keeps your mind working. Even while you are going about the non-literary part of your life—wiping your kids’ noses, doing the taxes, vacuuming the carpet—your writer’s brain is hard at work at a subconscious level, wrestling with a thorny problem although you’re not actively thinking about it. And that will make it all the easier for you to not only get started the next time you sit down to write, but to make actual headway on whatever it is you’re writing.

That’s the crux of this “priming” method: to have useable work to show for it at the end of the day. It may be a completed outline for a novel or non-fiction article. Or it may be a page, a scene, or even an entire chapter. Yes, these pages may “only” qualify as a first draft, but a solid one: much more than what I call “word salad,” a chaotic, loose jumble of raw ideas.

In one week of using this system, I have not only mapped out a plot route through the second half of my novel, but I’ve also generated this blog post, and written the lead to an article on omniscient POV on which I have been stalled for months.

Photo by Editor5807If this pump-priming method works as well for you as it has for me, then I hope you have a draft cohesive and clear enough that you can revise it without needing to either deconstruct it completely or throw it all away.

Photo by Editor5807If this pump-priming method works as well for you as it has for me, then I hope you have a draft cohesive and clear enough that you can revise it without needing to either deconstruct it completely or throw it all away. No method works for every writer, so there is no money-back guarantee for this free advice. :D But if you try it, I’d love to hear what your experience with Priming the Pump is.

Published on February 01, 2015 10:23

January 25, 2015

Morning pages? Epic fail, but new experiment coming

While I was laid up in a cast after Achilles tendon surgery the past two months, I decided to give Julia Cameron's morning pages a try, subjecting the fabled advice on creativity to a 30-day experiment. And for me at least, morning pages were a flop.

I make this declaration even though I enjoyed writing them every morning, and even though I felt they had some benefit. But they didn't achieve what I thought was their purpose—not just to unlock one's creativity in some vague and general sense, but rather to fuel a new burst of tangible, concrete productivity. This they did not do, not for me.

I make this declaration even though I enjoyed writing them every morning, and even though I felt they had some benefit. But they didn't achieve what I thought was their purpose—not just to unlock one's creativity in some vague and general sense, but rather to fuel a new burst of tangible, concrete productivity. This they did not do, not for me.

Now one can argue that I have misunderstood the raison d'être of morning pages, especially since, like the woman who wrote this sardonic blog post on "recovering" from The Artist's Way , I stubbornly refused to actually read any of Cameron's books. Instead, I relied on the instructions I found on Cameron's blog.

Perhaps Cameron never intended for morning pages to be as utilitarian as I wanted them to be. Maybe they are designed to be more like a routine tune-up for the creative spirit—something to lubricate the valves, clean the sludge out of the carburetor, and get the engine ready to run without worrying about whether the car ever leaves the driveway. But what I was hoping for was something that would actually propel me down the road, so I could rack up some real mileage on the odometer. And that didn't happen.

I did look forward to writing my 700 words—which is how I translated Cameron's prescription that one must complete three pages of longhand writing each day. For reasons that I explained in my previous blog post, I refused to do this by hand as Cameron prescribes. But I did do my pages first thing every morning, and yes, I did feel that it helped reconnect me each day to my identity as a writer. Certainly, that's a good thing.

But I still think they should be called morning purges, not pages. Because at the risk of being crude, they felt like the psychological equivalent of a visit to the bathroom, clearing one's self of all the emotional crap clogging up the works, making one lighter and freeing up the headspace to sit down to the day's work.

In other words, morning pages to me seem like nothing more esoteric or special than daily journaling. Period. End of sentence. And I was already doing that on a daily basis for the past eleven years, though at night rather than in the morning. And yes, it can be helpful. But it's a psychological/emotional/spiritual exercise, not a specifically creative one.

It's not what I need. This brought me back to freewriting, which I became familiar with via Natalie Goldberg's writings, though she wasn't the first to suggest them either. Dorothea Brande advised something similar in her 1932 classic, Becoming A Writer.

It's not what I need. This brought me back to freewriting, which I became familiar with via Natalie Goldberg's writings, though she wasn't the first to suggest them either. Dorothea Brande advised something similar in her 1932 classic, Becoming A Writer.

And apparently Jack Kerouac mentions something like the technique as well in his "Belief and Technique for Modern Prose."

Jack KerouacBut freewriting isn't necessarily aimed at helping you produce more useable prose at the end of the day's work either, and that's what I am looking for. Freewriting is like a key to switch on the ignition, when what I want is to get out of the garage and make it down the highway to the state line by sunset.

Jack KerouacBut freewriting isn't necessarily aimed at helping you produce more useable prose at the end of the day's work either, and that's what I am looking for. Freewriting is like a key to switch on the ignition, when what I want is to get out of the garage and make it down the highway to the state line by sunset.

So I'm playing around in my mind with a tiny spark of an idea, an adaptation of freewriting, one that has a more specific goal: to get my literary jalopy a certain number of miles down the road during each writing session. I'm not sure what to call it yet, and I'm not sure exactly what form it will take. But words like target, focus, specific, result, productivity, and useability are going to be key, I think.

Stay tuned for my next blog post to see what form this will take.

I make this declaration even though I enjoyed writing them every morning, and even though I felt they had some benefit. But they didn't achieve what I thought was their purpose—not just to unlock one's creativity in some vague and general sense, but rather to fuel a new burst of tangible, concrete productivity. This they did not do, not for me.

I make this declaration even though I enjoyed writing them every morning, and even though I felt they had some benefit. But they didn't achieve what I thought was their purpose—not just to unlock one's creativity in some vague and general sense, but rather to fuel a new burst of tangible, concrete productivity. This they did not do, not for me.Now one can argue that I have misunderstood the raison d'être of morning pages, especially since, like the woman who wrote this sardonic blog post on "recovering" from The Artist's Way , I stubbornly refused to actually read any of Cameron's books. Instead, I relied on the instructions I found on Cameron's blog.

Perhaps Cameron never intended for morning pages to be as utilitarian as I wanted them to be. Maybe they are designed to be more like a routine tune-up for the creative spirit—something to lubricate the valves, clean the sludge out of the carburetor, and get the engine ready to run without worrying about whether the car ever leaves the driveway. But what I was hoping for was something that would actually propel me down the road, so I could rack up some real mileage on the odometer. And that didn't happen.

I did look forward to writing my 700 words—which is how I translated Cameron's prescription that one must complete three pages of longhand writing each day. For reasons that I explained in my previous blog post, I refused to do this by hand as Cameron prescribes. But I did do my pages first thing every morning, and yes, I did feel that it helped reconnect me each day to my identity as a writer. Certainly, that's a good thing.

But I still think they should be called morning purges, not pages. Because at the risk of being crude, they felt like the psychological equivalent of a visit to the bathroom, clearing one's self of all the emotional crap clogging up the works, making one lighter and freeing up the headspace to sit down to the day's work.

In other words, morning pages to me seem like nothing more esoteric or special than daily journaling. Period. End of sentence. And I was already doing that on a daily basis for the past eleven years, though at night rather than in the morning. And yes, it can be helpful. But it's a psychological/emotional/spiritual exercise, not a specifically creative one.

It's not what I need. This brought me back to freewriting, which I became familiar with via Natalie Goldberg's writings, though she wasn't the first to suggest them either. Dorothea Brande advised something similar in her 1932 classic, Becoming A Writer.

It's not what I need. This brought me back to freewriting, which I became familiar with via Natalie Goldberg's writings, though she wasn't the first to suggest them either. Dorothea Brande advised something similar in her 1932 classic, Becoming A Writer.And apparently Jack Kerouac mentions something like the technique as well in his "Belief and Technique for Modern Prose."

Jack KerouacBut freewriting isn't necessarily aimed at helping you produce more useable prose at the end of the day's work either, and that's what I am looking for. Freewriting is like a key to switch on the ignition, when what I want is to get out of the garage and make it down the highway to the state line by sunset.

Jack KerouacBut freewriting isn't necessarily aimed at helping you produce more useable prose at the end of the day's work either, and that's what I am looking for. Freewriting is like a key to switch on the ignition, when what I want is to get out of the garage and make it down the highway to the state line by sunset. So I'm playing around in my mind with a tiny spark of an idea, an adaptation of freewriting, one that has a more specific goal: to get my literary jalopy a certain number of miles down the road during each writing session. I'm not sure what to call it yet, and I'm not sure exactly what form it will take. But words like target, focus, specific, result, productivity, and useability are going to be key, I think.

Stay tuned for my next blog post to see what form this will take.

Published on January 25, 2015 13:24

December 4, 2014

Rebel without a clue: is it truly necessary to freewrite longhand?

I am somewhat embarrassed to admit that after all my years as a writer and writing teacher, I have never read Julia Cameron's famous The Artist's Way. Recently one of my former students blogged about Cameron's advice to write so-called “morning pages” every day. They helped Mia find her way out of a painful creative desert, which provoked me to do a little research and find out what these morning pages are all about.

I am somewhat embarrassed to admit that after all my years as a writer and writing teacher, I have never read Julia Cameron's famous The Artist's Way. Recently one of my former students blogged about Cameron's advice to write so-called “morning pages” every day. They helped Mia find her way out of a painful creative desert, which provoked me to do a little research and find out what these morning pages are all about. Because what writer amongst us can't use inspiration? I know I can, especially now. I seem to be mired in a Sargasso of brain-lessness at the moment. I miss my morning walks, which seemed to open me up creatively each day. As I enter the fourth week of enforced immobility after Achilles tendon surgery last month, my mind as well as my leg seems to have stopped moving. I can barely concentrate long enough to read a book, much less write one myself.

And although I still haven't read Artist’s Way, I have read the author’s website about morning pages, and also several articles by other writers extolling what this practice has done for them. It strikes me that other than Cameron's prescription that these pages should be done first thing in the morning, this is the same technique that Natalie Goldberg recommended in her classic Writing Down the Bones.

And although I still haven't read Artist’s Way, I have read the author’s website about morning pages, and also several articles by other writers extolling what this practice has done for them. It strikes me that other than Cameron's prescription that these pages should be done first thing in the morning, this is the same technique that Natalie Goldberg recommended in her classic Writing Down the Bones.They both also stipulate that this freewriting be done longhand: with pen on paper, saying that this allows you in some undefined way to connect more authentically with your inner self. And this is where I'm going to rebel.

Why? It’s not because I’m a techno-snob. I love notebooks and pens. I've made almost a fetish of collecting them: Moleskines; Rhodias; Cartesios; handbound leather folios so gorgeous that I have never tainted the creamy acid-free pages by daring to actually write on them; even cheap Mead composition books that I sewed cute fabric covers for. I use a green clothbound notebook as my commonplace book where I lovingly inscribe quotes that appeal to me; I make a story bible out of a Moleskine each time I begin a big new writing project. I often organize my early ideas for stories in a notebook, using a cheap fountain pen whose ink flows freely onto the paper. So at times I do enjoy the pleasures—and ostensible virtues—of writing longhand.

But with apologies to Cameron and Goldberg, I’m not going to do my morning freewriting that way. I can list three good reasons why.

First, writing in a notebook isn't as private as writing on my computer, where I can password-protect something and later securely delete it for all eternity if I so desire. It's not that I'm going to divulge any deep dark secrets in my daily practice. But the free spirit in my brain will know that whatever I write could potentially be seen by someone, and that will inhibit me: creative constipation, I call it. I already have problems turning off my Inner Editor and writing as if no one were watching. So for me at least, writing longhand would negate any benefit of spontaneity that allegedly arises from writing longhand.

Second, I don't want to waste paper. Despite my love for notebooks [I've got an entire drawer full of temptingly blank ones just waiting for me to write something profound in them], I don't want to use them for what amounts to "junk writing" that is intended only to clear my clogged creative pipes, then be cast aside. Maybe it's the Scots in me, but it seems needlessly profligate to write on paper when I know in advance I’m just going to throw it in the trash. Better to do it with ephemeral electrons on a digital screen instead.

Third, since my neck fusion surgery two years ago, it is physically painful for me to write more than a paragraph or so by hand: my muscles seize up almost immediately. Although the surgery to relieve pressure on the spinal cord was successful, some of the [thankfully minor] nerve damage was nonetheless permanent.

So between the physical pain of writing longhand, and the mental constipation I would feel in knowing that what I was writing could be found and read by anyone, I am going to respectfully agree to disagree with both these wise writer women. I don’t think that spending thirty to forty minutes each day writing by hand is going to “unlock” me creatively if it’s an ordeal that I dread. No, my daily writing practice is going to be done with a keyboard, on either of my auxiliary brains.

What are those? Philosopher and cognitive scientist Andy Clark has written extensively about how *any* tool—from a paper notebook to to a laptop computer—can with repeated use become so much a part of an individual's thinking process that it effectively functions as an extension of his or her mind. For Cameron and Goldberg and many of their students, this externalized brain is a pen and notebook. For me, however, it is either my Macbook Air or my iPad.

The keyboard has long ago become a conduit to my brain. And it isn’t just a matter of typing speed or ease either. I have spent so many years composing at the keyboard that the very act of sitting down with my laptop flips a switch in my head. The words don’t just appear faster on the screen; the thoughts and ideas that precede the words flow freely and without impediment. It’s a very fluid process for me, one that taps into a wellspring of ideas within—and isn’t that the whole point of morning pages and freewriting?

Don’t get me wrong—I love to write longhand. It has a beauty and permanence for me—a kind of durability—that writing on a computer screen does not. And that’s yet another reason why I don’t want to do my morning pages this way. My understanding from perusing Cameron’s website is that the point of morning pages is not to cling to them. You write them to purge yourself of things that may be blocking you, to center yourself, to meditate on the page. And then you let it all go. Morning pages aren’t meant to be re-read or savored.

But when I write with pen and paper, I feel a sense of special reverence that would make me more inhibited in what I wrote, not less. When I commit something to paper, it feels like something I want to preserve forever. And so I would feel more inclined to pause and ponder, to debate every word with myself, and ultimately to sputter and stall out and stop writing completely.

Of course, your experience with freewriting might be very different from mine; every writer works in his or her own mysterious way. But for these final two weeks in a cast [at least I hope they are the last two weeks] while I am confined largely to my bed or recliner, this will be my grand experiment. I will see if I can jump start my idling brain by doing my personal variation on morning pages—but on my lap, with my iPad Air and an external keyboard.

I will let you know how it goes.

Published on December 04, 2014 06:15

November 10, 2014

The walking orthopedic disaster zone strikes again!

Meet Rowdy, my new ride for the next four to six weeks. Although I did manage to make it through October without heading to the OR—the first time in four years that has happened—the heady freedom didn’t last long. Because on Nov. 12th, I will be ending up in surgery after all, this time to repair my Achilles tendon. I will have to be off the leg completely for at least a month, part of the time in a cast: hence the nifty little red knee scooter. Do I know how to have fun or what?

And yes, I fully intend to decorate Rowdy with tinsel and a string of battery-operated lights for Christmas!

This surgery isn’t exactly a surprise. I’ve been hobbling around since last January on not just one but two bad Achilles tendons, which I ignored for as long as I could. Then I went through all the standard conservative treatments, including several weeks of painful physical therapy and a fashionable walking boot, but the tendons only continued to get worse. So finally my orthopedic surgeon—who really ought to name his next child after me, I’m such a good customer—said we could avoid the scalpel no longer. I got to choose which side to do first—because yes, I will have to have another surgery just like this one next year—and I picked the right leg, which is a bit worse.

I knew this surgery was looming even before my orthopod weighed in: my PTs were honest with me about how bad things were in my poor heels. So I took myself off in early October for what seemed like a decadently selfish thing to do: one week in the mountains, all by myself, so I could write. I’m so glad I did that. It helped me get back in touch with my own characters and stories after so much time helping other writers with theirs.

And who knows? Maybe the enforced down time after my surgery will give me the opportunity to have another writer’s retreat. It won’t be anywhere near as pleasant as my time in the mountains, but maybe it will still refresh my creative spirit.

Published on November 10, 2014 10:45

October 14, 2014

Why Lemony Snicket is my hero

“You cannot wait for an untroubled world to have an untroubled moment. The terrible phone call, the rainstorm, the sinister knock on the door—they will all come. Soon enough arrive the treacherous villain and the unfair trial and the smoke and the flames of the suspicious fires to burn everything away. In the meantime, it is best to grab what wonderful moments you find lying around.”

If anyone needed it, this quote from Lemony Snicket’s Shouldn’t You Be in School? is proof that children’s books aren’t all saccharine fluff and nonsense.

I know it's been months since my last post: a lot has been going on, and sadly today isn't the day for me to catch you up on it. [Though I did have a heavenly solo writer's retreat last week.]

I will pause long enough to say that over the past week I've been reading two middle grade series that appeal to my twisted and sometimes macabre sense of humor. The first series is Tales from Lovecraft Middle School, four books by the pseudonymous Charles Gilman that are like a cross between Goosebumps and the Cthulhu mythos. Some of my best memories of my late dad are of him telling us spooky stories that I later found out were written by H.P. Lovecraft. So Gilman "had me at hello" just with his titles.

The second series is All The Wrong Questions, a planned quartet of books in which Lemony shares a pivotal event from his apprenticeship at the age of thirteen in the secret VFD [Volunteer Fire Department]. If the famous Series of Unfortunate Events books were simultaneously an homage to and a parody of penny dreadfuls, then All the Wrong Questions does the same thing for Golden Age detective novels. There is even a noble librarian named Dashiell!

When I got to that quote about not waiting for a wonderful moment, I realized that was the very reason I fled to the mountains for my retreat in the first place. There never does seem to be an untroubled moment in which I can write. If it's not another round of surgery for me, it's needing to leave home to take care of my mother after she's had surgery. The central air conditioning dies and needs to be replaced, trees crash onto all three of our cars, the toilet chokes, the dog needs to go to the vet. And even when things are going well, there is always food to be bought and cooked, dishes to wash, floors to be swept, clothes to be folded, and carpets to be vacuumed. If it's not student or client manuscripts to edit, it's a new educational gig to stress over.

When I got to that quote about not waiting for a wonderful moment, I realized that was the very reason I fled to the mountains for my retreat in the first place. There never does seem to be an untroubled moment in which I can write. If it's not another round of surgery for me, it's needing to leave home to take care of my mother after she's had surgery. The central air conditioning dies and needs to be replaced, trees crash onto all three of our cars, the toilet chokes, the dog needs to go to the vet. And even when things are going well, there is always food to be bought and cooked, dishes to wash, floors to be swept, clothes to be folded, and carpets to be vacuumed. If it's not student or client manuscripts to edit, it's a new educational gig to stress over. This is true not just for me, but for all of you who are trying to write. None of us has a life filled with untroubled moments. But what I am learning, almost against my will, is that I need to stop waiting for those mythical halcyon times before I sit down to write. As Lemony tells us wisely, it's best to grab whatever moments we can find lying around in the midst of the daily chaos.

That's what I am trying to do today, with rain pouring down in sheets outside and tornado watches pending. Forget about all that, and just write.

I will leave you with another quote from Shouldn't You Be in School, this one by Lemony's imprisoned sister, Kit.

"“If you’re not scared, she told me, it’s not bravery.”

As I sit down to try and find my way back into my middle grade novel, I do feel a little shaky in the knees. Have I forgotten how to write? Is my idea stupid? Are my characters made of cardboard? Will kids find anything to like in this book? Is it worth writing at all?

So like Kit, I will be brave—and like Lemony, I will keep writing.

Published on October 14, 2014 08:47

July 24, 2014

Deep POV: Fast Track to Compelling Character Voice

Note: This is the fourth in a series of articles on demystifying viewpoint. The originals will appear first as posts on my Spontaneous Combustion blog, then be archived on my website as downloadable PDFs.

Deep POV is single viewpoint on steroids.

In the first article of this series, I compared single POV to viewing a scene through the eyeglasses of one particular character. Deep POV takes single POV and intensifies it. It's like putting two tiny cameras with powerful microscopic lenses in those glasses; installing microphones in the character's ears, and sensors in her nose, tongue, and skin; then finally inserting a silicon chip in her brain to channel every single thought, perception, sensation, and emotion directly to readers.

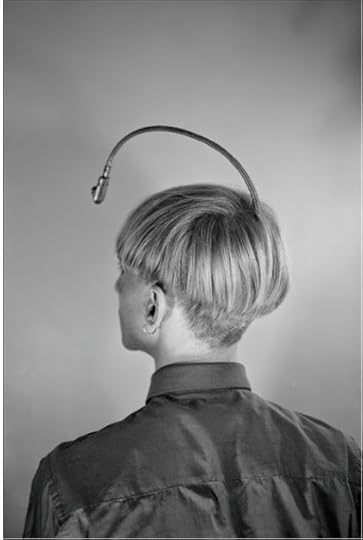

Lars Norgaard, "World's First Cyborg Artist" Handling POV like this is a fantastic way to immerse readers in your story. Although I'm not a gamer myself, it seems to me that Deep POV is like turning the protagonist of a novel into an avatar of the reader: the line between fictional character and reader of fiction gets blurred, so that the reader experiences the events of the plot as if they are happening to her. Readers slip so deeply inside the skin of a book's narrator that it's as if the two are fused into one.

Lars Norgaard, "World's First Cyborg Artist" Handling POV like this is a fantastic way to immerse readers in your story. Although I'm not a gamer myself, it seems to me that Deep POV is like turning the protagonist of a novel into an avatar of the reader: the line between fictional character and reader of fiction gets blurred, so that the reader experiences the events of the plot as if they are happening to her. Readers slip so deeply inside the skin of a book's narrator that it's as if the two are fused into one.

I told you Deep POV was intense!

The best way to get a feel for the difference between "regular" single POV and Deep POV is to read it in action. Here is a masterful example from the Okay for Now [Clarion 2001], a Newbery Honor book by the gifted children's writer, Gary D. Schmidt. The novel's narrator is eighth grader Doug Swietek. Here is he speaking about a Yankees baseball cap that his older brother had stolen.

This is Doug, talking straight to readers. There is absolutely no sense at all of any author sitting there with a pen or a typewriter or a computer making this up. Rather, Schmidt is writing as if he were possessed by Doug, being used by the character to transcribe his words onto the page. Now that's how to create a vivid, authentic, compelling character voice. Schmidt's novel is persuasive testimony of the power of Deep POV. There is no better way to bring a character to life.

Contrast this with regular single POV, in another wonderful middle grade novel, A Drowned Maiden's Hair [Candlewick Press 2006] by Laura Amy Schlitz.

"Maud had a hazy idea that the Battle Hymn had something to do with with war and slavery. She felt that by singing it she was defying authority and striking a blow against the general awfulness of the day."

"Maud had a hazy idea that the Battle Hymn had something to do with with war and slavery. She felt that by singing it she was defying authority and striking a blow against the general awfulness of the day."

Though this is single viewpoint, since it's written from within Maud's head, it is not Deep POV. It's phrases like she felt and Maud had a hazy idea that put readers at a subtle but real distance from the heroine.

The cumulative effect is a slightly more formal, slightly more adult voice. There is nothing wrong with this, but for me at least, it makes the ghost of the author more evident. I'm aware that there is a writer at work here; I don't feel that Maud is speaking directly to me.

"Duh!" you may object. "That's because Schlitz was writing in third person, and Schmidt was writing in first person, Nancy, you dolt." But it is possible to write Deep POV in third person. How? First, avoid writing anything that distances readers from your POV character in any way. Here's an example.

The phrase she heard is a tiny little wedge driven between the narrator and the reader. Do some quick and simple word-surgery, and you've gone a little deeper into your character's head.

You don't tell readers that she heard the slamming door, you simply show it happening—followed immediately by the character's response. So one way to achieve deeper POV is to follow the same old literary advice you've heard time and time again: show, don't tell.

In a similar vein, avoid distinguishing the narrator's thoughts in any way from the rest of the text. Certainly don't treat them like dialogue and set them aside in quotes, and don't italicize them either. That creates distance between your character and your readers. Also, don't apply what I call "thought tags," words such as thought, felt, surmised, guessed, supposed, etc. Again, just write the thought directly. For readers, this creates the sense that they are in the narrator's mind, hearing her thoughts by some kind of literary telepathy.

One of the places that it is easiest to slip up and forget to remain in Deep POV is in descriptive narrative. Writers—myself included—get carried away in describing a scene and start writing lyrical passages that their thirteen-year-old skateboarding hero would never say or think. Writing Deep POV is a humbling experience. With every word, you are trying to make readers forget that you, the author, exist. If you succeed, kids won’t even remember your name. Your goal is to convince them the main character is the one telling them the story, not you.

So it's definitely possible to write Deep POV in limited third person. But don't assume that you are automatically in Deep POV simply by virtue of writing in first person. I've read many first person narratives that remained aloof from the narrator. I see this mainly in student work, and when it happens, I think it's because the writer gets so caught up in setting down the events of the plot or what other characters are saying and doing that she forgets to let her narrator react to all of it.

Another way of putting that is to say that the POV glasses that the writer sets on her first-person narrator's face have clear lenses, as if the hero were a scientist recording "just the facts, ma'am." And who of us sees and responds to life in such a completely neutral fashion? It's the way a first-person narrator shares plot events and her observations of other characters that reveals to use what kind of person the narrator really is. There is color to the narrator's lenses.

[© Infrared photos by Nancy Butts]

[© Infrared photos by Nancy Butts]

A fine example of this is the Newbery-winning novel Jacob Have I Loved by Katherine Paterson. Told in first person, we believe that the cutting remarks Louise makes about her twin Caroline are accurate. It isn't until the end of the book that we realize that Louise has been envious of her sister all along, and that her observations have been tainted because she has been looking at her sister through green-colored glasses.

That taint is what you want when writing in first person: that is, if you want to achieve Deep POV. Let every word your narrator says—even if that is about something as ordinary as the weather, the menu in the school cafeteria, or the shoes his sister is wearing—reveal more about your hero than perhaps he'd like to admit.

That taint is what you want when writing in first person: that is, if you want to achieve Deep POV. Let every word your narrator says—even if that is about something as ordinary as the weather, the menu in the school cafeteria, or the shoes his sister is wearing—reveal more about your hero than perhaps he'd like to admit.

I've read articles and books that are almost prescriptions or recipes for how to do Deep POV, but I'm not sure that's the most helpful way to look at it. You don't have to go "all in." Such intense identification with a main character can get claustrophobic, especially if she is whiny, depressed,or unpleasant in some way. Not being able to get out of her head for even one moment can turn readers off. So you need to choose your project well. If you've got an anti-hero, or a character who might initially seem unlikeable for one reason or the other [perhaps the point of your book is show their transformation], Deep POV may not be the technique to choose, not exclusively.

Perhaps you could use it only for brief passages, borrowing techniques from Deep POV so we can hear your main viewpoint character's voice loud and proud. To me, and to many editors and readers, the voice of your protagonist is what makes a book stand out. What makes a thousand books about yet another dysfunctional family forgettable, and one book like Okay for Now so memorable that it haunts you for weeks after you finish it? Character voice. And one of the most powerful techniques for creating that is Deep POV. What better reason is there to learn as much as you can about it?

[© 2014 This article is subject to copyright. Please do not use or reproduce without express written permission from the author.]

Next in the series—Once Upon a Time: Does Omniscient POV Make Your Book Old-Fashioned?

Deep POV is single viewpoint on steroids.

In the first article of this series, I compared single POV to viewing a scene through the eyeglasses of one particular character. Deep POV takes single POV and intensifies it. It's like putting two tiny cameras with powerful microscopic lenses in those glasses; installing microphones in the character's ears, and sensors in her nose, tongue, and skin; then finally inserting a silicon chip in her brain to channel every single thought, perception, sensation, and emotion directly to readers.

Lars Norgaard, "World's First Cyborg Artist" Handling POV like this is a fantastic way to immerse readers in your story. Although I'm not a gamer myself, it seems to me that Deep POV is like turning the protagonist of a novel into an avatar of the reader: the line between fictional character and reader of fiction gets blurred, so that the reader experiences the events of the plot as if they are happening to her. Readers slip so deeply inside the skin of a book's narrator that it's as if the two are fused into one.

Lars Norgaard, "World's First Cyborg Artist" Handling POV like this is a fantastic way to immerse readers in your story. Although I'm not a gamer myself, it seems to me that Deep POV is like turning the protagonist of a novel into an avatar of the reader: the line between fictional character and reader of fiction gets blurred, so that the reader experiences the events of the plot as if they are happening to her. Readers slip so deeply inside the skin of a book's narrator that it's as if the two are fused into one.I told you Deep POV was intense!

The best way to get a feel for the difference between "regular" single POV and Deep POV is to read it in action. Here is a masterful example from the Okay for Now [Clarion 2001], a Newbery Honor book by the gifted children's writer, Gary D. Schmidt. The novel's narrator is eighth grader Doug Swietek. Here is he speaking about a Yankees baseball cap that his older brother had stolen.

"I guess now it's in a gutter, getting rained on or something. Probably anyone who walks by looks down and thinks it's a piece of junk. They're right. That's all it is. Now. But once, it was the only thing I ever owned that hadn't belonged to some Swieteck before me."

This is Doug, talking straight to readers. There is absolutely no sense at all of any author sitting there with a pen or a typewriter or a computer making this up. Rather, Schmidt is writing as if he were possessed by Doug, being used by the character to transcribe his words onto the page. Now that's how to create a vivid, authentic, compelling character voice. Schmidt's novel is persuasive testimony of the power of Deep POV. There is no better way to bring a character to life.

Contrast this with regular single POV, in another wonderful middle grade novel, A Drowned Maiden's Hair [Candlewick Press 2006] by Laura Amy Schlitz.

"Maud had a hazy idea that the Battle Hymn had something to do with with war and slavery. She felt that by singing it she was defying authority and striking a blow against the general awfulness of the day."

"Maud had a hazy idea that the Battle Hymn had something to do with with war and slavery. She felt that by singing it she was defying authority and striking a blow against the general awfulness of the day."Though this is single viewpoint, since it's written from within Maud's head, it is not Deep POV. It's phrases like she felt and Maud had a hazy idea that put readers at a subtle but real distance from the heroine.

The cumulative effect is a slightly more formal, slightly more adult voice. There is nothing wrong with this, but for me at least, it makes the ghost of the author more evident. I'm aware that there is a writer at work here; I don't feel that Maud is speaking directly to me.

"Duh!" you may object. "That's because Schlitz was writing in third person, and Schmidt was writing in first person, Nancy, you dolt." But it is possible to write Deep POV in third person. How? First, avoid writing anything that distances readers from your POV character in any way. Here's an example.

She jumped when she heard the door slam.

The phrase she heard is a tiny little wedge driven between the narrator and the reader. Do some quick and simple word-surgery, and you've gone a little deeper into your character's head.

The door slammed. She jumped, her heart ping-ponging in her chest.

You don't tell readers that she heard the slamming door, you simply show it happening—followed immediately by the character's response. So one way to achieve deeper POV is to follow the same old literary advice you've heard time and time again: show, don't tell.

In a similar vein, avoid distinguishing the narrator's thoughts in any way from the rest of the text. Certainly don't treat them like dialogue and set them aside in quotes, and don't italicize them either. That creates distance between your character and your readers. Also, don't apply what I call "thought tags," words such as thought, felt, surmised, guessed, supposed, etc. Again, just write the thought directly. For readers, this creates the sense that they are in the narrator's mind, hearing her thoughts by some kind of literary telepathy.

One of the places that it is easiest to slip up and forget to remain in Deep POV is in descriptive narrative. Writers—myself included—get carried away in describing a scene and start writing lyrical passages that their thirteen-year-old skateboarding hero would never say or think. Writing Deep POV is a humbling experience. With every word, you are trying to make readers forget that you, the author, exist. If you succeed, kids won’t even remember your name. Your goal is to convince them the main character is the one telling them the story, not you.

So it's definitely possible to write Deep POV in limited third person. But don't assume that you are automatically in Deep POV simply by virtue of writing in first person. I've read many first person narratives that remained aloof from the narrator. I see this mainly in student work, and when it happens, I think it's because the writer gets so caught up in setting down the events of the plot or what other characters are saying and doing that she forgets to let her narrator react to all of it.

Another way of putting that is to say that the POV glasses that the writer sets on her first-person narrator's face have clear lenses, as if the hero were a scientist recording "just the facts, ma'am." And who of us sees and responds to life in such a completely neutral fashion? It's the way a first-person narrator shares plot events and her observations of other characters that reveals to use what kind of person the narrator really is. There is color to the narrator's lenses.

[© Infrared photos by Nancy Butts]

[© Infrared photos by Nancy Butts]A fine example of this is the Newbery-winning novel Jacob Have I Loved by Katherine Paterson. Told in first person, we believe that the cutting remarks Louise makes about her twin Caroline are accurate. It isn't until the end of the book that we realize that Louise has been envious of her sister all along, and that her observations have been tainted because she has been looking at her sister through green-colored glasses.

That taint is what you want when writing in first person: that is, if you want to achieve Deep POV. Let every word your narrator says—even if that is about something as ordinary as the weather, the menu in the school cafeteria, or the shoes his sister is wearing—reveal more about your hero than perhaps he'd like to admit.

That taint is what you want when writing in first person: that is, if you want to achieve Deep POV. Let every word your narrator says—even if that is about something as ordinary as the weather, the menu in the school cafeteria, or the shoes his sister is wearing—reveal more about your hero than perhaps he'd like to admit.I've read articles and books that are almost prescriptions or recipes for how to do Deep POV, but I'm not sure that's the most helpful way to look at it. You don't have to go "all in." Such intense identification with a main character can get claustrophobic, especially if she is whiny, depressed,or unpleasant in some way. Not being able to get out of her head for even one moment can turn readers off. So you need to choose your project well. If you've got an anti-hero, or a character who might initially seem unlikeable for one reason or the other [perhaps the point of your book is show their transformation], Deep POV may not be the technique to choose, not exclusively.

Perhaps you could use it only for brief passages, borrowing techniques from Deep POV so we can hear your main viewpoint character's voice loud and proud. To me, and to many editors and readers, the voice of your protagonist is what makes a book stand out. What makes a thousand books about yet another dysfunctional family forgettable, and one book like Okay for Now so memorable that it haunts you for weeks after you finish it? Character voice. And one of the most powerful techniques for creating that is Deep POV. What better reason is there to learn as much as you can about it?

[© 2014 This article is subject to copyright. Please do not use or reproduce without express written permission from the author.]

Next in the series—Once Upon a Time: Does Omniscient POV Make Your Book Old-Fashioned?

Published on July 24, 2014 12:12

June 11, 2014

Why are trees throwing themselves at me?

There goes my writing retreat!

© Photo by Nancy Butts

© Photo by Nancy Butts

I am even sadder this morning than I was yesterday evening when I lost my "writing pecan" tree. I had spent several hours yesterday in its shade, blocking out a new outline for the second half of my middle grade novel. Around 5, I ran out of steam, so I packed up my portable office and began to move inside. I had just sat down at my computer to make sure that the day's work was backed up, when out of nowhere the winds started gusting and there was a sudden downpour of rain.

I heard a crack, but it wasn't so loud or so close that I thought it was anything in my yard. One of the neighbors lost a tree limb, I thought.

And then I heard my husband shouting. A microburst had completely uprooted my writing pecan, which had toppled down across all three cars, brushing the edge of the roof we just had replaced last year due to hail damage, and ending up with a few branches on the back porch. And to think that I had just been sitting at that table under the tree, not twenty minutes earlier. Brrrr.

The holly tree took the brunt of the pecan's weight, which saved my husband's car. The lid to the trunk will have to be replaced, but I think that's it. But both the holly and another pecan were severely injured when the first tree fell: hope we can save them, or I won't have any shade in my backyard at all. Where am I going to hang all my ghosts at Halloween?

And where am I going to write now?

My car escaped without damage, but my son's old junker is still buried under the mammoth trunk of the tree. My son launched into lumberjack mode, and the three of us were able to cut out enough of the branches to get my husband's car out and moved to a safer place, but we're now at a place where professionals need to step in. Sigh. We just finished replacing the air conditioning system last week; today we'll be dealing with insurance agents, adjusters, body shops, and tree removers.

This is the second time in six months that a tree has thrown itself at me. In January during the first ice storm, I was out walking—and please don't ask what kind of idiot goes out for a stroll in the midst of an ice storm—when a huge oak at the Baptist church suddenly crashed down just a split second after I had walked past it. It fell only a few feet behind me. I love trees so much I'm practically a Druid, so why do they keep committing suicide around me? :D

But most of all, I'm going to miss that beautiful old pecan.

© Photo by Nancy Butts

© Photo by Nancy ButtsI am even sadder this morning than I was yesterday evening when I lost my "writing pecan" tree. I had spent several hours yesterday in its shade, blocking out a new outline for the second half of my middle grade novel. Around 5, I ran out of steam, so I packed up my portable office and began to move inside. I had just sat down at my computer to make sure that the day's work was backed up, when out of nowhere the winds started gusting and there was a sudden downpour of rain.

I heard a crack, but it wasn't so loud or so close that I thought it was anything in my yard. One of the neighbors lost a tree limb, I thought.

And then I heard my husband shouting. A microburst had completely uprooted my writing pecan, which had toppled down across all three cars, brushing the edge of the roof we just had replaced last year due to hail damage, and ending up with a few branches on the back porch. And to think that I had just been sitting at that table under the tree, not twenty minutes earlier. Brrrr.

The holly tree took the brunt of the pecan's weight, which saved my husband's car. The lid to the trunk will have to be replaced, but I think that's it. But both the holly and another pecan were severely injured when the first tree fell: hope we can save them, or I won't have any shade in my backyard at all. Where am I going to hang all my ghosts at Halloween?

And where am I going to write now?

My car escaped without damage, but my son's old junker is still buried under the mammoth trunk of the tree. My son launched into lumberjack mode, and the three of us were able to cut out enough of the branches to get my husband's car out and moved to a safer place, but we're now at a place where professionals need to step in. Sigh. We just finished replacing the air conditioning system last week; today we'll be dealing with insurance agents, adjusters, body shops, and tree removers.

This is the second time in six months that a tree has thrown itself at me. In January during the first ice storm, I was out walking—and please don't ask what kind of idiot goes out for a stroll in the midst of an ice storm—when a huge oak at the Baptist church suddenly crashed down just a split second after I had walked past it. It fell only a few feet behind me. I love trees so much I'm practically a Druid, so why do they keep committing suicide around me? :D

But most of all, I'm going to miss that beautiful old pecan.

Published on June 11, 2014 04:29

June 3, 2014

Summer haven: or my micro-writer's retreat

Summer's upon us, and in a house full of academics—namely, my husband and son, both of whom are college professors—that means that everyone is on vacation. Everyone except me, that is.