D.W. Wilkin's Blog, page 25

September 25, 2016

Regency Personalities Series-Charles Yorke 4th Earl of Hardwicke

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Admiral Charles Phillip Yorke 4th Earl of Hardwicke

2 April 1799 – 17 September 1873

Charles Yorke

Charles Yorke 4th Earl of Hardwicke was born at Sydney Lodge, in Hamble le Rice, Hardwicke was the eldest son of Admiral Sir Joseph Sydney Yorke, second son of Charles Yorke, Lord Chancellor, by his second wife, Agneta Johnson. He was a nephew of Philip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke. He was educated at Harrow and at the Royal Naval College, where he was awarded the second medal.

Hardwicke entered the Royal Navy in May 1815 as midshipman on HMS Prince, the flagship at Spithead. Later, he served in the Mediterranean, on HMS Sparrowhawk (18) and HMS Leviathan (74) then subsequently HMS Queen Charlotte (100), the flagship of Lord Exmouth, by whom he was entrusted with the command of a gunboat at the bombardment of Algiers. He later joined HMS Leander (60) under the flag of Sir David Milne, on the North American station, where he was given the command of the Jane, a small vessel carrying dispatches between Halifax and Bermuda. He was then appointed acting lieutenant of HMS Grasshopper (18) and after a few months commissioned in the rank of lieutenant in August 1819. The next October, he joined the frigate HMS Phaeton on the Halifax station, until appointed to the command of HMS Alacrity in 1823 on the Mediterranean station, in this post he was employed, before and after he obtained the rank of captain in 1825, in watching the movements of the Turko-Egyptian forces and in the suppression of piracy.

Between 1828 and 1831, he took command of HMS Alligator (28), on the same station and took an active part in the naval operation in connection with the struggle between Greece and Turkey. Lastly, between 1844 and 1845, for short periods, he assumed command of the steam yacht HMS Black Eagle and HMS St Vincent (120), in which he carried the Emperor of Russia, Nicholas I, to England. He attained flag rank in 1838. In 1849, while commanding HMS Vengeance, he participated in the repression of the republican rebellion of Genoa in support of the forces of the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Vengeance also fired on the Hospital of Pammatone, causing 107 civilian casualties. For these actions, he was decorated by the Sardinian King Victor Emmanuel II with two medals he was authorized to accept by Queen Victoria only in 1855. In 1858, he retired from the active list with the rank of rear-admiral, becoming vice-admiral in the same year, and admiral in 1863. He retired from the Royal Navy in 1870.

Hardwicke represented Reigate in the House of Commons between 1831 and 1832 and Cambridgeshire between 1832 and 1834. In 1834, on the death of his uncle, he became the fourth Earl of Hardwicke, and inherited the substantial Wimpole estate in Cambridgeshire. He was a member of Lord Derby’s cabinet in 1852 as Postmaster General and as Lord Privy Seal between 1858 and 1859. In 1852 he was sworn of the Privy Council.

Lord Hardwicke married the Honourable Susan Liddell, sixth daughter of Thomas Liddell, 1st Baron Ravensworth, in August 1833. They had five sons and three daughters. He died in September 1873, aged 74, and was succeeded in the earldom by his eldest son, Charles. The Countess of Hardwicke died in November 1886.

He also supposedly fathered an illegitimate child by one Charlotte Pratt, a serving girl at his Wimpole Hall home. Charlotte got married in 1849, and the following was noted in the marriage register:

The year before this marriage, 18-year-old servant girl Charlotte gave birth to a son, James Pratt, who was baptised on 2 April 1848. The father was understood to have been her employer, the 4th Earl of Hardwicke. “Charlotte… was a Pratt; and she was a picture. The handsomest woman that I ever remember to have seen. In harvest time to see her swinging along the road with a bundle of corn balanced on her head, both arms akimbo, was a study in colour, figure and poise”. – A.C.Yorke

RAP (Regency Assembly Press) in need of Beta-Readers

Regency Assembly

Press

is looking for

Beta Readers

One novel is ready for Beta Reading

We have a continuation of Pride and Prejudice with Ms Caroline Bingley and her fortune at stake:

Do we think that Mr Hurst married his Bingley Bride without incentive? It is highly probable that Caroline Bingley, even though she has a sharp, acerbic tongue, still is in possession of a fortune and an astute fortune hunter who deciphers this may soon be on the road to, if not a happy marriage, one with financial security.

Please respond or send an email if you are interested

An Unofficial Guide to how to win the Scenarios of Rollercoaster Tycoon 3 Soaked and Wild

An Unofficial Guide to how to win the Scenarios of Rollercoaster Tycoon 3, Soaked! and WILD!

I have been a fan of this series of computer games since early in its release of the very first game. That game was done by one programmer, Chris Sawyer, and it was the first I recall of an internet hit. Websites were put up in dedication to this game where people showed off their creations, based on real amusement parks. These sites were funded by individuals, an expense that was not necessarily as cheap then as it is now. Nor as easy to program then as it might be to build a web page now.

Prima Books released game guides for each iteration of the game, Rollercoaster Tycoon 1, Rollercoaster Tycoon 2 and Rollercoaster Tycoon 3 (RCT3) but not for the expansion sets. And unlike the first two works, the third guide was riddled with incorrect solutions. As I played the game that frustrated me. And I took to the forums that Atari, the game publisher hosted to see if I could find a way to solve those scenarios that the Prima Guide had written up in error. Not finding any good advice, I created my own for the scenarios that the “Official” Guide had gotten wrong.

Solutions that if you followed my advice you would win the scenario and move on. But if you followed the

“Official” version you would fail and not be able to complete the game. My style and format being different than the folks at Prima, I continued for all the Scenarios that they had gotten right as well, though my solutions cut to the chase and got you to the winner’s circle more quickly, more directly.

My contributions to the “Official” Forum, got me a place as a playtester for both expansions to the game, Soaked and Wild. And for each of these games, I wrote the guides during the play testing phase so all the play testers could solve the scenarios, and then once again after the official release to make changes in the formula in case our aiding to perfect the game had changed matters. For this, Atari and Frontier (the actual programmers of the game) placed me within the game itself.

And for the longest time, these have been free at the “Official” Forums, as well as my own website dedicated to the game. But a short time ago, I noticed that Atari, after one of its bankruptcies had deleted their forums. So now I am releasing the Guide for one and all. I have added new material and it is over 150 pages, for all three games. It is available for the Kindle at present for $7.99. It is also available as a trade paperback for just a little bit more.

You can also find this at Smashwords, iBooks, Kobo and Barnes and Noble

(Click on the picture to purchase)

Not only are all 39 Scenarios covered, but there are sections covering every Cheat Code, Custom Scenery, the famous Small Park Competition, the Advanced Fireworks Editor, the Flying Camera Route Editor which are all the techniques every amusement park designer needs to make a fantastic park in Rollercoaster Tycoon 3.

Scenarios for RCT 3

1) Vanilla Hills

2) Goldrush

3) Checkered Flag

4) Box Office

5) Fright Night

6) Go With The Flow

7) Broom Lake

8) Valley of Kings

9) Gunslinger

10) Ghost Town

11) National Treasure

12) New Blood

13) Island Hopping

14) Cosmic Crags

15) La La Land

16) Mountain Rescue

17) The Money Pit

18) Paradise Island

Scenarios for Soaked!

1) Captain Blackheart’s Cove

2) Oasis of Fun

3) Lost Atlantis

4) Monster Lake

5) Fountain of Youth

6) World of the Sea

7) Treasure Island

8) Mountain Spring

9) Castaway Getaway

Scenarios for WILD!

1) Scrub Gardens

2) Ostrich Farms Plains

3) Egyptian Sand Dance

4) A Rollercoaster Odyssey

5) Zoo Rescue

6) Mine Mountain

7) Insect World

8) Rocky Coasters

9) Lost Land of the Dinosaurs

10) Tiger Forest

11) Raiders of the Lost Coaster

12) Saxon Farms

September 24, 2016

Regency Personalities Series-Sir George Best Robinson 2nd Baronet

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Sir George Best Robinson 2nd Baronet

14 November 1797 – 1855

Sir George Best Robinson 2nd Baronet was the son of Sir George Robinson, 1st Baronet and Margaret Southwell, the natural daughter of Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Suffolk, he succeeded to the baronetcy on 13 February 1832.

Between 1818-19 he was employed as a supercargo by the East India Company in Canton, (now known as Guangzhou).

He was appointed third Superintendent of British Trade in China alongside Lord Napier and John Francis Davis in December 1833. After Napier’s death in 1834, Davis and Robinson moved up to become chief and second superintendents.

Robinson became Chief Superintendent on 19 January 1835 following the resignation of John Francis Davis with John Harvey Astell and Charles Elliot as second and third superintendents. He maintained a “perfectly quiescent line of policy” during his tenure and reported a “quiet and prosperous routine of trade”. To maintain this state of affairs and to avoid the necessity of British ships obtaining port clearance in Macao, in November 1835, Robinson left the British Factory in Canton after announcing that he would henceforth operate from aboard the cutter Louisa moored off Lintin Island outside the Bocca Tigris. British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerton effectively dismissed Robinson in line with “the intention of His Majesty’s Government to reduce the establishment in China” through a dispatch dated 7 June 1836, in which he wrote:

“It, therefore, now becomes my duty to acquaint you, that His Majesty’s Government have decided to abolish at once the office and salary of Chief Superintendent. In communicating to you this decision, I have at the same time to inform you, that your functions will cease from the date of the receipt of this despatch. You will make over. to Captain Elliot all the archives of the Commission; which will, of course, include copies of every despatch, and its inclosures (sic), which you have addressed to this department during the period you have acted as Chief Superintendent.

The Spectator later commented:

“The conclusion can hardly be resisted, that to get rid of Sir GEORGE ROBINSON, Lord PALMERSTON abolished the office, with the intention of restoring it for Captain ELLIOT’S benefit with the purpose of enabling British subjects to violate the laws of the country to which they trade. Any loss, therefore, which such persons may suffer in consequence of the more effectual execution of the Chinese laws on this subject, must be borne by the parties who have brought that loss on themselves by their own acts.”

On 5 December 1825, Robinson married Louisa, youngest daughter of Major-Gen. Robert Douglas Diarist Harriet Low recorded on 5 April 1832 that Robinson and his wife: “are both six feet tall and no beauty to boast of; very well matched as regards intellect, and not at all troubled by the fashions of the world.” The Morning Post reported that Louisa died in London on 9 August 1843. He was at that time resident at Furzebrook House in Axminster, Devon. On 7 January 1863 the couple’s only daughter, Louisa, married John Prideaux Lightfoot, the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University

Space Opera Books presents ECO Agents:Save The Planet a Young Adult Adventure

First ECO Agents book available

Those who follow me for a long time know that I also write in other fields aside from Regency Romance and the historical novels I do.

A few months ago, before the end of last year and after 2011 NaNoWriMo, (where I wrote the first draft of another Regency) I started work on a project with my younger brother Douglas (All three of my brothers are younger brothers.)

The premise, as he is now an educator but once was a full on scientist at the NHI and FBI (Very cloak and dagger chemistry.) was that with the world having become green, and more green aware every week, why not have a group of prodigies, studying at a higher learning educational facility tackle the ills that have now begun to beset the world.

So it is now released. We are trickling it out to the major online channels and through Amazon it will be available in trade paperback. Available at Amazon for your Kindle, or your Kindle apps and other online bookstores. For $5.99 you can get this collaboration between the brothers Wilkin. Or get it for every teenager you know who has access to a Kindle or other eReader.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook Smashwords iBookstore for your Apple iDevices Amazon for your Kindle

Five young people are all that stands between a better world and corporate destruction. Parker, Priya, JCubed, Guillermo and Jennifer are not just your average high school students. They are ECOAgents, trusted the world over with protecting the planet.

Our Earth is in trouble. Humanity has damaged our home. Billionaire scientist turned educator, Dr. Daniel Phillips-Lee, is using his vast resources to reverse this situation. Zedadiah Carter, leader of the Earth’s most powerful company, is only getting richer, harvesting resources, with the aid of not so trustworthy employees.

When the company threatens part of the world’s water supply, covering up their involvement is business as usual. The Ecological Conservation Organization’s Academy of Higher Learning and Scientific Achievement, or simply the ECO Academy, high in the hills of Malibu, California overlooking the Pacific Ocean, is the envy of educational institutions worldwide.

The teenage students of the ECO Academy, among the best and brightest the planet has to offer, have decided they cannot just watch the world self-destruct. They will meet this challenge head on as they begin to heal the planet.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it

September 23, 2016

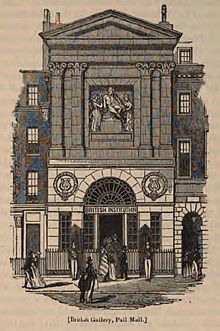

Regency Personalities Series-Boydell Shakespeare Gallery

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Boydell Shakespeare Gallery

4 May 1789 – (after) 28 January 1805

Boydell Shakespeare Gallery

Boydell Shakespeare Gallery project contained three parts: an illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s plays; a folio of prints from the gallery (originally intended to be a folio of prints from the edition of Shakespeare’s plays); and a public gallery where the original paintings for the prints would hang.

The idea of a grand Shakespeare edition was conceived during a dinner at the home of Josiah Boydell (John’s nephew) in late 1786. Five important accounts of the occasion survive. From these, a guest list and a reconstruction of the conversation have been assembled. The guest list reflects the range of Boydell’s contacts in the artistic world: it included Benjamin West, painter to King George III; George Romney, a renowned portrait painter; George Nicol, bookseller to the king; William Hayley, a poet; John Hoole, a scholar and translator of Tasso and Aristotle; and Daniel Braithwaite, secretary to the postmaster general and a patron of artists such as Romney and Angelica Kauffman. Most accounts also place the painter Paul Sandby at the gathering.

Boydell wanted to use the edition to help stimulate a British school of history painting. He wrote in the “Preface” to the folio that he wanted “to advance that art towards maturity, and establish an English School of Historical Painting”. A court document used by Josiah to collect debts from customers after Boydell’s death relates the story of the dinner and Boydell’s motivations:

[Boydell said] he should like to wipe away the stigma that all foreign critics threw on this nation—that they had no genius for historical painting. He said he was certain from his success in encouraging engraving that Englishmen wanted nothing but proper encouragement and a proper subject to excel in historical painting. The encouragement he would endeavor to find if a proper subject were pointed out. Mr. Nicol replied that there was one great National subject concerning which there could be no second opinion, and mentioned Shakespeare. The proposition was received with acclaim by the Alderman [John Boydell] and the whole company.

However, as Frederick Burwick argues in his introduction to a collection of essays on the Boydell Gallery, “[w]hatever claims Boydell might make about furthering the cause of history painting in England, the actual rallying force that brought the artists together to create the Shakespeare Gallery was the promise of engraved publication and distribution of their works.”

After the initial success of the Shakespeare Gallery, many wanted to take credit. Henry Fuseli long claimed that his planned Shakespeare ceiling (in imitation of the Sistine Chapel ceiling) had given Boydell the idea for the gallery. James Northcote claimed that his Death of Wat Tyler and Murder of the Princes in the Tower had motivated Boydell to start the project. However, according to Winifred Friedman, who has researched the Boydell Gallery, it was probably Joshua Reynolds’s Royal Academy lectures on the superiority of history painting that influenced Boydell the most.

The logistics of the enterprise were difficult to organise. Boydell and Nicol wanted to produce an illustrated edition of a multi-volume work and intended to bind and sell the 72 large prints separately in a folio. A gallery was required to exhibit the paintings from which the prints were drawn. The edition was to be financed through a subscription campaign, during which the buyers would pay part of the price up front and the remainder on delivery. This unusual practice was necessitated by the fact that over £350,000—an enormous sum at the time, worth about £38.8 million today—was eventually spent. The gallery opened in 1789 with 34 paintings and added 33 more in 1790 when the first engravings were published. The last volume of the edition and the Collection of Prints were published in 1803. In the middle of the project, Boydell decided that he could make more money if he published different prints in the folio than in the illustrated edition; as a result, the two sets of images are not identical.

Advertisements were issued and placed in newspapers. When a subscription was circulated for a medal to be struck, the copy read: “The encouragers of this great national undertaking will also have the satisfaction to know, that their names will be handed down to Posterity, as the Patrons of Native Genius, enrolled with their own hands, in the same book, with the best of Sovereigns.” The language of both the advertisement and the medal emphasised the role each subscriber played in the patronage of the arts. The subscribers were primarily middle-class Londoners, not aristocrats. Edmund Malone, himself an editor of a rival Shakespeare edition, wrote that “before the scheme was well-formed, or the proposals entirely printed off, near six hundred persons eagerly set down their names, and paid their subscriptions to a set of books and prints that will cost each person, I think, about ninety guineas; and on looking over the list, there were not above twenty names among them that anybody knew”.

The “magnificent and accurate” Shakespeare edition which Boydell began in 1786 was to be the focus of his enterprise—he viewed the print folio and the gallery as offshoots of the main project. In an advertisement prefacing the first volume of the edition, Nicol wrote that “splendor and magnificence, united with correctness of text were the great objects of this Edition”. The volumes themselves were handsome, with gilded pages that, unlike those in previous scholarly editions, were unencumbered by footnotes. Each play had its own title page followed by a list of “Persons in the Drama”. Boydell spared no expense. He hired the typography experts William Bulmer and William Martin to develop and cut a new typeface specifically for the edition. Nicol explains in the preface that they “established a printing-house … [and] a foundry to cast the types; and even a manufactory to make the ink”. Boydell also chose to use high-quality wove Whatman paper. The illustrations were printed independently and could be inserted and removed as the purchaser desired. The first volumes of the Dramatic Works were published in 1791 and the last in 1805.

Boydell was responsible for the “splendor”, and George Steevens, the general editor, was responsible for the “correctness of text”. Steevens, according to Evelyn Wenner, who has studied the history of the Boydell edition, was “at first an ardent advocate of the plan” but “soon realized that the editor of this text must in the very scheme of things give way to painters, publishers and engravers”. He was also ultimately disappointed in the quality of the prints, but he said nothing to jeopardize the edition’s sales. Steevens, who had already edited two complete Shakespeare editions, was not asked to edit the text anew; instead, he picked which version of the text to reprint. Wenner describes the resulting hybrid edition:

The thirty-six plays, printed from the texts of Reed and Malone, divide into the following three groups: (1) five plays of the first three numbers printed from Reed’s edition of 1785 with many changes adopted from the Malone text of 1790 (2) King Lear and the six plays of the next three numbers printed from Malone’s edition of 1790 but exhibiting conspicuous deviations from his basic text (3) twenty-four plays of the last twelve numbers also printed from Malone’s text but made to conform to Steevens’s own edition of 1793.

Throughout the edition, modern (i.e. 18th-century) spelling was preferred as were First Folio readings.

Boydell sought out the most eminent painters and engravers of the day to contribute paintings for the gallery, engravings for the folio, and illustrations for the edition. Artists included Richard Westall, Thomas Stothard, George Romney, Henry Fuseli, Benjamin West, Angelica Kauffman, Robert Smirke, John Opie, Francesco Bartolozzi, Thomas Kirk, Henry Thomson, and Boydell’s nephew and business partner, Josiah Boydell.

The folio and the illustrated Shakespeare edition were “by far the largest single engraving enterprise ever undertaken in England”. As print collector and dealer Christopher Lennox-Boyd explains, “had there not been a market for such engravings, not one of the paintings would have been commissioned, and few, if any, of the artists would have risked painting such elaborate compositions”. Scholars believe that a variety of engraving methods were employed and that line engraving was the “preferred medium” because it was “clear and hardwearing” and because it had a high reputation. Stipple engraving, which was quicker and often used to produce shading effects, wore out quicker and was valued less. Many plates were a mixture of both. Several scholars have suggested that mezzotint and aquatint were also used. Lennox-Boyd, however, claims that “close examination of the plates confirms” that these two methods were not used and argues that they were “totally unsuitable”: mezzotint wore quickly and aquatint was too new (there would not have been enough artists capable of executing it). Most of Boydell’s engravers were also trained artists; for example, Bartolozzi was renowned for his stippling technique.

Boydell’s relationships with his illustrators were generally congenial. One of them, James Northcote, praised Boydell’s liberal payments. He wrote in an 1821 letter that Boydell “did more for the advancement of the arts in England than the whole mass of the nobility put together! He paid me more nobly than any other person has done; and his memory I shall ever hold in reverence”. Boydell typically paid the painters between £105 to £210, and the engravers between £262 and £315. Joshua Reynolds at first declined Boydell’s offer to work on the project, but he agreed when pressed. Boydell offered Reynolds carte blanche for his paintings, giving him a down payment of £500, an extraordinary amount for an artist who had not even agreed to do a specific work. Boydell eventually paid him a total of £1,500.

There are 96 illustrations in the nine volumes of the illustrated edition and each play has at least one. Approximately two-thirds of the plays, 23 out of 36, are each illustrated by a single artist. Approximately two-thirds of the total number of illustrations, or 65, were completed by three artists: William Hamilton, Richard Westall, and Robert Smirke. The primary illustrators of the edition were known as book illustrators, whereas a majority of the artists included in the folio were known for their paintings. Lennox-Boyd argues that the illustrations in the edition have a “uniformity and cohesiveness” that the folio lacks because the artists and engravers working on them understood book illustration while those working on the folio were working in an unfamiliar medium.

The print folio, A Collection of Prints, From Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakspeare, by the Artists of Great-Britain (1805), was originally intended to be a collection of the illustrations from the edition, but a few years into the project, Boydell altered his plan. He guessed that he could sell more folios and editions if the pictures were different. Of the 97 prints made from paintings, two-thirds of them were made by ten of the artists. Three artists account for one-third of the paintings. In all, 31 artists contributed works.

In June 1788, Boydell and his nephew secured the lease on a site at 52 Pall Mall (51°30′20.5″N 0°8′12″W) to build the gallery and engaged George Dance, then the Clerk of the City Works, as the architect for the project. Pall Mall at that time had a mix of expensive residences and commercial operations, such as bookshops and gentleman’s clubs, popular with fashionable London society. The area also contained some less genteel establishments: King’s Place (now Pall Mall Place), an alley running to the east and behind Boydell’s gallery, was the site of Charlotte Hayes’s high-class brothel. Across King’s Place, immediately to the east of Boydell’s building, 51 Pall Mall had been purchased on 26 February 1787 by George Nicol, bookseller and future husband of Josiah’s elder sister, Mary Boydell. As an indication of the changing character of the area, this property had been the home of Goostree’s gentleman’s club from 1773 to 1787. Begun as a gambling establishment for wealthy young men, it had later become a reformist political club that counted William Pitt and William Wilberforce as members.

Dance’s Shakespeare Gallery building had a monumental, neoclassical stone front, and a full-length exhibition hall on the ground floor. Three interconnecting exhibition rooms occupied the upper floor, with a total of more than 4,000 square feet (370 m2) of wall space for displaying pictures. The two-storey façade was not especially large for the street, but its solid classicism had an imposing effect. Some reports describe the exterior as “sheathed in copper”.

The lower storey of the façade was dominated by a large, rounded-arched doorway in the centre. The unmoulded arch rested on wide piers, each broken by a narrow window, above which ran a simple cornice. Dance placed a transom across the doorway at the level of the cornice bearing the inscription “Shakespeare Gallery”. Below the transom were the main entry doors, with glazed panels and side lights matching the flanking windows. A radial fanlight filled the lunette above the transom. In each of the spandrels to the left and right of the arch, Dance set a carving of a lyre inside a ribboned wreath. Above all this ran a panelled band course dividing the lower storey from the upper.

The upper façade contained paired pilasters on either side, and a thick entablature and triangular pediment. The architect Sir John Soane criticised Dance’s combination of slender pilasters and a heavy entablature as a “strange and extravagant absurdity”. The capitals topping the pilasters sported volutes in the shape of ammonite fossils. Dance invented this neo-classical feature, which became known as the Ammonite Order, specifically for the gallery. In a recess between the pilasters, Dance placed Thomas Banks’s sculpture Shakespeare attended by Painting and Poetry, for which the artist was paid 500 guineas. The sculpture depicted Shakespeare, reclining against a rock, between the Dramatic Muse and the Genius of Painting. Beneath it was a panelled pedestal inscribed with a quotation from Hamlet: “He was a Man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again”.

The Shakespeare Gallery, when it opened on 4 May 1789, contained 34 paintings, and by the end of its run it had between 167 and 170. (The exact inventory is uncertain and most of the paintings have disappeared; only around 40 paintings can be identified with any certainty.) According to Frederick Burwick, during its sixteen-year operation, the Gallery reflected the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism. Works by artists such as James Northcote represent the conservative, neoclassical elements of the gallery, while those of Henry Fuseli represent the newly emerging Romantic movement. William Hazlitt praised Northcote in an essay entitled “On the Old Age of Artists”, writing “I conceive any person would be more struck with Mr. Fuseli at first sight, but would wish to visit Mr. Northcote oftener.”

The gallery itself was a fashionable hit with the public. Newspapers carried updates of the construction of the gallery, down to drawings for the proposed façade. The Daily Advertiser featured a weekly column on the gallery from May through August (exhibition season). Artists who had influence with the press, and Boydell himself, published anonymous articles to heighten interest in the gallery, which they hoped would increase sales of the edition.

At the beginning of the enterprise, reactions were generally positive. The Public Advertiser wrote on 6 May 1789: “the pictures in general give a mirror of the poet … [The Shakespeare Gallery] bids fair to form such an epoch in the History of the Fine Arts, as will establish and confirm the superiority of the English School”. The Times wrote a day later:

This establishment may be considered with great truth, as the first stone of an English School of Painting; and it is peculiarly honourable to a great commercial country, that it is indebted for such a distinguished circumstance to a commercial character—such an institution—will place, in the Calendar of Arts, the name of Boydell in the same rank with the Medici of Italy.

Fuseli himself may have written the review in the Analytical Review, which praised the general plan of the gallery while at the same time hesitating: “such a variety of subjects, it may be supposed, must exhibit a variety of powers; all cannot be the first; while some must soar, others must skim the meadow, and others content themselves to walk with dignity”. However, according to Frederick Burwick, critics in Germany “responded to the Shakespeare Gallery with far more thorough and meticulous attention than did the critics in England”.

Criticism increased as the project dragged on: the first volume did not appear until 1791. James Gillray published a cartoon labelled “Boydell sacrificing the Works of Shakespeare to the Devil of Money-Bags”. The essayist and soon-to-be co-author of the children’s book Tales from Shakespeare (1807) Charles Lamb criticised the venture from the outset:

What injury did not Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery do me with Shakespeare. To have Opie’s Shakespeare, Northcote’s Shakespeare, light headed Fuseli’s Shakespeare, wooden-headed West’s Shakespeare, deaf-headed Reynolds’ Shakespeare, instead of my and everybody’s Shakespeare. To be tied down to an authentic face of Juliet! To have Imogen’s portrait! To confine the illimitable!

Northcote, while appreciating Boydell’s largesse, also criticised the results of the project: “With the exception of a few pictures by Joshua [Reynolds] and [John] Opie, and—I hope I may add—myself, it was such a collection of slip-slop imbecility as was dreadful to look at, and turned out, as I had expected it would, in the ruin of poor Boydell’s affairs”.

By 1796, subscriptions to the edition had dropped by two-thirds. The painter and diarist Joseph Farington recorded that this was a result of the poor engravings:

West said He looked over the Shakespeare prints and was sorry to see them of such inferior quality. He said that excepting that from His Lear by Sharpe, that from Northcote’s children in the Tower, and some small ones, there were few that could be approved. Such a mixture of dotting and engraving, and such a general deficiency in respect of drawing which He observed the Engravers seemed to know little of, that the volumes presented a mass of works which He did not wonder many subscribers had declined to continue their subscription.

The mix of engraving styles was criticised; line engraving was considered the superior form and artists and subscribers disliked the mixture of lesser forms with it. Moreover, Boydell’s engravers fell behind schedule, delaying the entire project. He was forced to engage lesser artists, such as Hamilton and Smirke, at a lower price to finish the volumes as his business started to fail. Modern art historians have generally concurred that the quality of the engravings, particularly in the folio, was poor. Moreover, the use of so many different artists and engravers led to a lack of stylistic cohesion.

Although the Boydells ended with 1,384 subscriptions, the rate of subscriptions dropped, and remaining subscriptions were also increasingly in doubt. Like many businesses at the time, the Boydell firm kept few records. Only the customers knew what they had purchased. This caused numerous difficulties with debtors who claimed they had never subscribed or had subscribed for less. Many subscribers also defaulted, and Josiah Boydell spent years after John’s death attempting to force them to pay.

The Boydells focused all their attention on the Shakespeare edition and other large projects, such as The History of the River Thames and The Complete Works of John Milton, rather than on lesser, more profitable ventures. When both the Shakespeare enterprise and the Thames book failed, the firm had no capital to fall back upon. Beginning in 1789, with the onset of the French revolution, John Boydell’s export business to Europe was cut off. By the late 1790s and early 19th century, the two-thirds of his business that depended upon the export trade was in serious financial difficulty.

In 1804, John Boydell decided to appeal to Parliament for a private bill to authorise a lottery to dispose of everything in his business. The bill received royal assent on 23 March, and by November the Boydells were ready to sell tickets. John Boydell died before the lottery was drawn on 28 January 1805, but lived long enough to see each of the 22,000 tickets purchased at three guineas apiece (£250 each in modern terms)

Space Opera Books Presents A Trolling We Will Go Omnibus:The Latter Years

A Trolling We Will Go Omnibus:The Latter Years

Not only do I write Regency and Romance, but I also have delved into Fantasy.

The Trolling series, is the story of a man, Humphrey. We meet him as he has left youth and become a man with a man’s responsibilities. He is a woodcutter for a small village. It is a living, but it is not necessarily a great living. It does give him strength, muscles.

We follow him in a series of stories that encompass the stages of life. We see him when he starts his family, when he has older sons and the father son dynamic is tested.

We see him when his children begin to marry and have children, and at the end of his life when those he has loved, and those who were his friends proceed him over the threshold into death.

All this while he serves a kingdom troubled by monsters. Troubles that he and his friends will learn to deal with and rectify.

Here are the last two books together as one longer novel.

Trolling, Trolling, Trolling Fly Hides! and We’ll All Go a Trolling.

Available in a variety of formats.

For $5.99 you can get this fantasy adventure.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook

The stories of Humphrey and Gwendolyn. Published separately in: Trolling, Trolling, Trolling Fly Hides! and We’ll All Go a Trolling. These are the tales of how a simple Woodcutter who became a king and an overly educated girl who became his queen helped save the kingdom of Torahn from an ancient evil. Now with the aid of their children and their grandchildren.

Long forgotten is the way to fight the Trolls. Beasts that breed faster than rabbits it seems, and when they decide to migrate to the lands of humans, their seeming invulnerability spell doom for all in the kingdom of Torahn. Not only Torahn but all the human kingdoms that border the great mountains that divide the continent.

The Kingdom of Torahn has settled down to peace, but the many years of war to acheive that peace has seen to changes in the nearby Teantellen Mountains. Always when you think the Trolls have also sought peace, you are fooled for now, forced by Dragons at the highest peaks, the Trolls are marching again.

Now Humphrey is old, too old to lead and must pass these cares to his sons. Will they be as able as he always has been. He can advise, but he does not have the strength he used to have. Nor does Gwendolyn back in the Capital. Here are tales of how leaders we know and are familiar with must learn to trust the next generation to come.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it

September 22, 2016

Regency Personalities Series-William Henry Ireland

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

William Henry Ireland

2 August 1775 – 17 April 1835

William Henry Ireland

William Henry Ireland claimed throughout his life that he was born in London in 1777, recently discovered evidence puts his birth two years earlier, on 2 August 1775. His father, Samuel Ireland, was a successful publisher of travelogues, collector of antiquities and collector of Shakespearian plays and “relics”. There was at the time, and still is, a great paucity of writing in the hand of Shakespeare. Of his 37 plays, there is not one copy in his own writing, not a scrap of correspondence from Shakespeare to a friend, fellow writer, patron, producer or publisher. Forgery would fill this void.

William Henry also became a collector of books. In many later recollections Ireland described his fascination with the works and the glorious death of the forger Thomas Chatterton, and probably knew the Ossian poems of James Macpherson. He was strongly influenced by the 1780 novel Love and Madness by Herbert Croft, which was often read aloud in the Ireland house, and which contained large sections on Chatterton and Macpherson. When he was apprenticed to a mortgage lawyer, Ireland began to experiment with blank, genuinely old papers and forged signatures on them. Eventually he forged several documents until he was ready to present them to his father.

In December 1794, William told his father that he had discovered a cache of old documents belonging to an acquaintance who wanted to remain unnamed, and that one of them was a deed with a signature of Shakespeare in it. He gave the document – which he had of course made himself – to his overjoyed father, who had been looking for just that kind of signature for years.

A letter supposedly written by Shakespeare (forged by Ireland) expressing gratitude towards the Earl of Southampton.

Ireland went on to make more findings – a promissory note, a written declaration of Protestant faith, letters to Anne Hathaway (with a lock of hair attached), and to Queen Elizabeth – all supposedly in Shakespeare’s hand. He claimed that all came from the chest of the anonymous friend. He “found” books with Shakespeare’s notes in the margins and “original” manuscripts for Hamlet and King Lear. The experts of the day authenticated them all.

On 24 December 1795, Samuel Ireland published his own book about the papers, a lavishly illustrated and expensively produced set of facsimiles and transcriptions of the papers called Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments under the Hand and Seal of William Shakespeare (the book bears the publication date 1796). More people took interest in the matter and the plot began to unravel.

In 1795, Ireland became bolder and produced a whole new play – Vortigern and Rowena. After extensive negotiations, Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan acquired rights for the first production of the play at London’s Drury Lane Theatre for £300, and a promise of half of all profits to the Irelands.

Sheridan read the play and noticed it was relatively simplistic compared to Shakespeare’s other works. John Philip Kemble, actor and manager of Drury Lane Theatre, later claimed he had serious doubts about its authenticity; he also suggested that the play appear on April Fool’s Day, though Samuel Ireland objected, and the play was moved to the next day.

Although the Shakespeare papers had prominent believers (including James Boswell), sceptics had questioned their authenticity from the beginning, and as the premiere of Vortigern approached, the press was filled with arguments over whether the papers were genuine or forgeries. On 31 March 1796, Shakespearean scholar Edmond Malone published his own exhaustive study, An Inquiry into the Authenticity of Certain Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments, about the supposed papers. His attack on the papers, stretching to more than 400 densely printed pages, showed convincingly that the papers could be nothing other than modern forgeries. Although believers tried to hold their ground, scholars were convinced by Malone’s arguments.

Vortigern and Rowena opened on 2 April 1796, just two days after Malone’s book appeared. Contemporary accounts differ in details, but most agree the first three acts went smoothly, and the audience listened respectfully. Late in the play, though, Kemble used the chance to hint at his opinion by repeating Vortigern’s line “and when this solemn mockery is o’er.” Malone’s supporters had filled the theatre, and the play was greeted with the audience’s catcalls. The play had only one performance, and was not revived until 2008.

When critics closed in and accused Samuel Ireland of forgery, his son published a confession – An Authentic Account of the Shaksperian Manuscripts – but many critics could not believe a young man could have forged them all by himself. One paper published a caricature in which William Henry is awed by the findings when the rest of the family forges more of them (as opposed to what was really going on). Samuel Ireland’s reputation did not recover before his death in 1800.

In 1805 William Henry published The Confessions of William Henry Ireland, but confession did not help his reputation. He took on a number of miscellaneous jobs as a hack writer but always found himself short of money. In 1814 he moved to France and worked in the French national library, continuing to publish books in London all the while. When he returned in 1823, he resumed his life of penury. In 1832 he published his own edition of Vortigern and Rowena (his father had originally published it in 1799) as his own play with very little success.

There has been recent scholarly interest in his later Gothic novels and his poetry. His illustrated Histories were popular, so to say that Ireland died in obscurity is probably not correct. He was, however, perpetually impoverished; he spent time in debtors’ prison, and was constantly forced to borrow money from friends and strangers. When he died, his widow and daughters applied to the Literary Fund for relief. They received only token amounts.

An Unofficial Guide to how to win the Scenarios of Soaked the 1st Expansion for Rollercoaster Tycoon 3

An Unofficial Guide to how to win the Scenarios of Soaked

I have been a fan of this series of computer games since early in its release of the very first game. That game was done by one programmer, Chris Sawyer, and it was the first I recall of an internet hit. Websites were put up in dedication to this game where people showed off their creations, based on real amusement parks. These sites were funded by individuals, an expense that was not necessarily as cheap then as it is now. Nor as easy to program then as it might be to build a web page now.

Prima Books released game guides for each iteration of the game, Rollercoaster Tycoon 1, Rollercoaster Tycoon 2 and Rollercoaster Tycoon 3 (RCT3) but not for the expansion sets. And unlike the first two works, the third guide was riddle with incorrect solutions. As I played the game that frustrated me. And I took to the forums that Atari, the game publisher hosted to see if I could find a way to solve those scenarios that the Prima Guide had written up in error. Not finding any good advice, I created my own for the scenarios that the “Official” Guide had gotten wrong.

Solutions that if you followed my advice you would win the scenario and move on. But if you followed the “Official” version you would fail and not be able to complete the game. My style and format being different than the folks at Prima, I continued for all the Scenarios that they had gotten right as well, though my solutions cut to the chase and got you to the winner’s circle more quickly, more directly.

My contributions to the “Official” Forum, got me a place as a playtester for both expansions to the game, Soaked and Wild. And for each of these games, I wrote the guides during the play testing phase so all the play testers could solve the scenarios, and then once again after the official release to make changes in the formula in case our aiding to perfect the game had changed matters. For this, Atari and Frontier (the actual programmers of the game) placed me within the game itself.

And for the longest time, these have been free at the “Official” Forums, as well as my own website dedicated to the game. But a short time ago, I noticed that Atari, after one of its bankruptcies had deleted their forums. So now I am releasing the Guide for one and all. I have added new material and it is near 100 pages, just for the first of the three games. It is available for the Kindle at present for $2.99.

(Click on the picture to purchase)

Not only are all 9 Scenarios covered, but there are sections covering every Cheat Code, Custom Scenery, the famous Small Park Competition, the Advanced Fireworks Editor, the Flying Camera Route Editor which are all the techniques every amusement park designer needs to make a fantastic park in Rollercoaster Tycoon 3.

Scenarios for Soaked!

1) Captain Blackheart’s Cove

2) Oasis of Fun

3) Lost Atlantis

4) Monster Lake

5) Fountain of Youth

6) World of the Sea

7) Treasure Island

8) Mountain Spring

9) Castaway Getaway

September 21, 2016

Regency Personalities Series-Mary (Nisbet) Hamilton Bruce Countess of Elgin

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Mary (Nisbet) Hamilton Bruce Countess of Elgin

18 April 1778 – 9 July 1855

Mary (Nisbet) Hamilton Bruce

Mary (Nisbet) Hamilton Bruce Countess of Elgin was born in Dirleton. Her parents were of the landed gentry; William Hamilton Nisbet was a Scottish landowner, one of the few who owned large estates in Scotland. Her mother, also called Mary (née Manners) was a granddaughter of John Manners, 2nd Duke of Rutland. Nisbet grew up on the Archerfield Estate, not far from Edinburgh. From an early age she kept a detailed diary. During her teens Nisbet’s father became a Member of Parliament, and the family traveled to London, where she entered society via her grandmother, Lady Robert Manners. According to biographer Susan Nagel, “she was noted to be very mature for her age and often joined her parents at gatherings traditionally held for grown-ups.”

Mary Nisbet met Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, who had only recently become Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, in 1798. The pair were distantly related via the Montagus and were considered a good match by both families. They married on 11 March 1799. After spending the wedding night at Archerfield the couple travelled to Bruce’s home in Broomhall, Fife.

Following a short stint in London the couple left England on 3 September 1799 so that Bruce could take up his ambassadorial position; sailing from Portsmouth on the HMS Phaeton. By this point Nisbet was pregnant but decided to travel with her new husband. During the two-month voyage they visited Lisbon and Gibraltar (as guests of Charles O’Hara), Sicily, Palermo, Messina and Tenodoes before arriving in Constantinople.

It was a difficult time in Constantinople; English people were not well liked or trusted. The couple moved into the old French embassy (which had recently been vacated) which Mary Bruce then had decorated and where she hosted lavish parties. In November, with the permission of the Grand Vizier, she became the first woman to attend a political Ottoman ceremony. Despite being five months pregnant she was required to dress as a man.

The Bruces had five children; two sons and three daughters:

George Charles Constantine (1800–1840), died unmarried and before his father, known by the courtesy title of Lord Bruce.

Mary, married on 28 January 1828, Robert Dundas

Matilda-Harrie, married on 14 October 1839, John Maxwell, son and heir of Sir John Maxwell, 7th Baronet

William, died young of illness on April 8, 1805. It is debated whether or not William was the child of Lord Elgin.

Lucy, married on 14 March 1828, John Grant of Perthshire

Bruce divorced Nisbet in either 1807 or 1808, and she went on to marry Robert Ferguson of Raith (1777–1846).