D.W. Wilkin's Blog, page 178

October 3, 2014

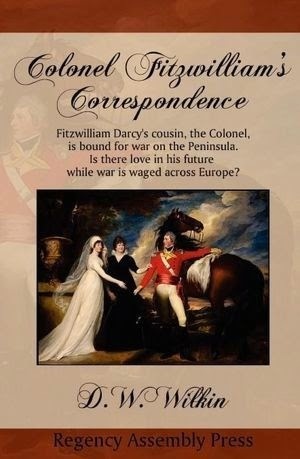

A Jane Austen Sequel: Colonel Fitzwilliam’s Correspondence

Colonel Fitzwilliam’s Correspondence For your enjoyment, one of the Regency Romances I published.

It is available for sale and I hope that you will take the opportunity to order your copy.

For yourself or as a gift. It is now available in a variety of formats.

For just a few dollars this Regency Romance can be yours for your eReaders or physically in Trade Paperback.

Visit the dedicated Website

Barnes and Noble for your Nook or in Paperback

Amazon for your Kindle or in Trade Paperback

Witnessing his cousin marry for love and not money, as he felt destined to do, Colonel Fitzwilliam refused to himself to be jealous. He did not expect his acquaintance with the Bennet Clan to change that.

Catherine Bennet, often called Kitty, had not given a great deal of thought to how her life might change with her sisters Elizabeth and Jane becoming wed to rich and connected men. Certainly meeting Darcy’s handsome cousin, a Colonel, did not affect her.

But one had to admit that the connections of the Bingleys and Darcys were quite advantageous. All sorts of men desired introductions now that she had such wealthy new brothers.

Kitty knew that Lydia may have thought herself fortunate when she had married Wickham, the first Bennet daughter to wed. Kitty, though, knew that true fortune had come to her. She just wasn’t sure how best to apply herself.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

October 2, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Richard Hurd

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Richard Hurd

13 January 1720 – 28 May 1808

Richard Hurd

Richard Hurd was born at Congreve, in the parish of Penkridge, Staffordshire, where his father was a farmer. He was educated at Brewood Grammar School and at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He took his B.A. degree in 1739, and in 1742 he proceeded M.A. and became a fellow of his college. In the same year he was ordained deacon, and given charge of the parish of Reymerston, Norfolk, but he returned to Cambridge early in 1743. He was ordained priest in 1744. In 1748 he published some Remarks on an Enquiry into the Rejection of Christian Miracles by the Heathens (1746), by William Weston, a fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge.

He prepared editions, which won the praise of Edward Gibbon, of the Ars poetica and Epistola ad Pisones (1749), and the Epistola ad Augustum (1751) of Horace. A compliment in the preface to the edition of 1749 was the starting-point of a lasting friendship with William Warburton, through whose influence he was appointed one of the preachers at Whitehall in 1750. In 1765 he was appointed preacher at Lincoln’s Inn, and in 1767 he became archdeacon of Gloucester.

In 1768, he proceeded D.D. at Cambridge, and delivered at Lincoln’s Inn the first Warburton lectures, which were published later (1772) as An Introduction to the Study of the Prophecies concerning the Christian Church. He became bishop of Lichfield and Coventry in 1774, and two years later was selected to be tutor to the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York. In 1781 he was translated to the see of Worcester. He lived chiefly at Hartlebury Castle, where he built a fine library, to which he transferred Alexander Pope’s and Warburton’s books, purchased on the latter’s death.

He was extremely popular at court, and in 1783, on the death of Archbishop Cornwallis, the king pressed him to accept the primacy, but Hurd, who was known, says Madame d’Arblay, as “The Beauty of Holiness,” declined it as a charge not suited to his temper and talents, and much too heavy for him to sustain. He died, unmarried, on 28 May 1808.

He bequeathed his library to his successors as bishop, and it remains at Hartlebury Castle, but its fate remains uncertain, now that the castle has ceased to be used as the bishop’s residence.

Hurd’s Letters on Chivalry and Romance (1762) retain a certain interest for their importance in the history of the romantic movement, which they did something to stimulate. They were written in continuation of a dialogue on the age of Queen Elizabeth included in his Moral and Political Dialogues (1759) Two later dialogues On the Uses of Foreign Travel were printed in 1763. Hurd wrote two acrimonious defences of Warburton On the Delicacy of Friendship (1755), in answer to John Jortin and a Letter (1764) to Dr Thomas Leland, who had criticized Warburton’s Doctrine of Grace. He edited the Works of William Warburton, the Select Works (1772) of Abraham Cowley, and left materials for an edition (6 vols., 1811) of Addison. His own works appeared in a collected edition in 8 vols. 1811.

Space Opera Books Presents A Trolling We Will Go Omnibus:The Latter Years

A Trolling We Will Go Omnibus:The Latter Years

Not only do I write Regency and Romance, but I also have delved into Fantasy.

The Trolling series, is the story of a man, Humphrey. We meet him as he has left youth and become a man with a man’s responsibilities. He is a woodcutter for a small village. It is a living, but it is not necessarily a great living. It does give him strength, muscles.

We follow him in a series of stories that encompass the stages of life. We see him when he starts his family, when he has older sons and the father son dynamic is tested.

We see him when his children begin to marry and have children, and at the end of his life when those he has loved, and those who were his friends proceed him over the threshold into death.

All this while he serves a kingdom troubled by monsters. Troubles that he and his friends will learn to deal with and rectify.

Here are the last two books together as one longer novel.

Trolling, Trolling, Trolling Fly Hides! and We’ll All Go a Trolling.

Available in a variety of formats.

For $5.99 you can get this fantasy adventure.

Barnes and Noble for your Nook

The stories of Humphrey and Gwendolyn. Published separately in: Trolling, Trolling, Trolling Fly Hides! and We’ll All Go a Trolling. These are the tales of how a simple Woodcutter who became a king and an overly educated girl who became his queen helped save the kingdom of Torahn from an ancient evil. Now with the aid of their children and their grandchildren.

Long forgotten is the way to fight the Trolls. Beasts that breed faster than rabbits it seems, and when they decide to migrate to the lands of humans, their seeming invulnerability spell doom for all in the kingdom of Torahn. Not only Torahn but all the human kingdoms that border the great mountains that divide the continent.

The Kingdom of Torahn has settled down to peace, but the many years of war to acheive that peace has seen to changes in the nearby Teantellen Mountains. Always when you think the Trolls have also sought peace, you are fooled for now, forced by Dragons at the highest peaks, the Trolls are marching again.

Now Humphrey is old, too old to lead and must pass these cares to his sons. Will they be as able as he always has been. He can advise, but he does not have the strength he used to have. Nor does Gwendolyn back in the Capital. Here are tales of how leaders we know and are familiar with must learn to trust the next generation to come.

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

October 1, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Granville Sharp

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Granville Sharp

10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813

Granville Sharp

Granville Sharpwas the son of Thomas Sharp (1693–1759), Archdeacon of Northumberland, prolific theological writer and biographer of his father, John Sharp, Archbishop of York. Sharp was born in Durham in 1735. He had eight older brothers and five younger sisters. Five of his brothers survived their infancy and by the time Sharp had reached his midteens the family funds set aside for their education had been all but depleted, so Sharp was educated at Durham School but mainly at home.

He was apprenticed to a London linen-draper at the age of fifteen. Sharp loved to argue and debate, and his keen intellect found little outlet in the mundane work in which he was involved. However, one of his fellow-apprentices was Socinian (a Unitarian sect that denied the divinity of Christ), and in order better to argue, Sharp taught himself Greek. Another fellow apprentice was Jewish, and so Sharp learned Hebrew in order to be able to discuss theological matters with his colleague. Sharp also conducted genealogical research for one of his masters, Henry Willoughby, who had a claim to the barony of Willoughby de Parham, and it was through Sharp’s work that Willoughby was able to take his place in the House of Lords.

Sharp’s apprenticeship ended in 1757, and both his parents died a year later. That same year he accepted a position as Clerk in the Ordnance Office at the Tower of London. This civil service position allowed him plenty of free time to pursue his scholarly and intellectual pursuits.

Sharp had a keen musical interest. Four of his siblings – William, later to become surgeon to George III, James, Elizabeth and Judith – had also come to London, and they met every day. They all played musical instruments as a family orchestra, giving concerts at William’s house in Mincing Lane and later in the family sailing barge, Apollo, which was moored at the Bishop of London’s steps in Fulham, near William’s country home, Fulham House. The fortnightly water-borne concerts took place from 1775–1783, the year his brother James died. Sharp had an excellent bass voice, described by George III as “the best in Britain”, and he played the clarinet, oboe, flageolet, kettle drums, harp and a double-flute which he had made himself. He often signed his name in notes to friends as G#.

Sharp died at Fulham House on 6 July 1813, and a memorial of him was erected in Westminster Abbey. He lived in Fulham, London, and was buried in the churchyard of All Saints Church, Fulham. The vicar would not allow a funeral sermon to be preached in the church because Sharp had been involved with the British and Foreign Bible Society, which was Nonconformist.

Sharp is best known for his untiring efforts for the abolition of slavery, although he was involved in many other causes, fired by a dislike of any social or legal injustice.

Sharp’s brother William held a regular surgery for the local poor at his surgery at Mincing Lane, and one day in 1765 when Sharp was visiting, he met Jonathan Strong. Strong was a young black slave from Barbados who had been so badly beaten by his master, David Lisle, a lawyer, that he had been cast out into the street as useless. Sharp and his brother tended to his injuries and had him admitted to Barts Hospital, where his injuries were so bad they necessitated a four-month stay. The Sharps paid for his treatment and, when he was fit enough, found him employment with a Quaker apothecary friend of theirs. In 1767, Lisle saw Strong in the street and had him kidnapped and sold to a planter called James Kerr for £30. Strong was able to get word to Sharp, and in a court attended by the Lord Mayor and the Coroner of London, Lisle and Kerr were denied possession of Strong. They instituted a court action against Sharp claiming £200 damages for taking their property, and Lisle challenged Sharp to a duel—Sharp told Lisle that he could expect satisfaction from the law.

Sharp consulted lawyers and found that as the law stood it favoured the master’s rights to his slaves as property: that a slave remained in law the chattel of his master even on English soil. Sharp said “he could not believe the law of England was really so injurious to natural rights.” He spent the next two years in study of English law, especially where it applied to the liberty of the individual.

Lisle disappeared from the records early, but Kerr persisted with his suit through eight legal terms before it was dismissed, and Kerr was ordered to pay substantial damages for wasting the court’s time. Jonathan Strong was free, even if the law had not been changed, but he only lived for five years as a free man, dying at 25.

The Strong case made a name for Sharp as the “protector of the Negro” and he was approached by two more slaves, although in both cases (Hylas v Newton and R v Stapylton) the results were unsatisfactory, and it became plain that the judiciary – and Lord Mansfield, the Chief Justice of the King’s Bench (the leading judge of the day) in particular – was trying very hard not to decide the issue. By this time, Great Britain was by far the largest trafficker in slaves, transporting more Africans across the Atlantic than all other nations put together, and the slave trade and slave labour were important to the British economy.

In 1769 Sharp published A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery …, the first tract in England attacking slavery.

On 13 January 1772, Sharp was visited and asked for help by James Somersett, a slave from Virginia in America, who had come to England with his master Charles Stewart in 1769 and had run away in October 1771. After evading slave hunters employed by Stewart for 56 days, Somersett had been caught and put in the slave ship Ann and Mary, to be taken to Jamaica and sold. Three Londoners had applied to Lord Mansfield for a writ of habeas corpus, which had been granted, with Somersett having to appear at a hearing on 24 January 1772. Members of the public responded to Somersett’s plight by sending money to pay for his lawyers (who in the event all gave their services pro bono publico), while Stewart’s costs were met by the West Indian planters and merchants.

Calling on his now-formidable knowledge of the law regarding individual liberty, Sharp briefed Somersett’s lawyers. Mansfield’s prevarications stretched Somersett’s Case over six hearings from January to May, and he finally delivered his judgment on 22 June 1772. It was a clear victory for Somersett, Sharp and the lawyers who acted for Somersett: Mansfield acknowledged that English law did not allow slavery, and only a new Act of Parliament (“positive law”) could bring it into legality. However, the verdict in the case is often misunderstood to mean the end of slavery in England. It was no such thing: it only dealt with the question of the forcible sending of someone overseas into bondage; a slave becomes free the moment he sets foot on English territory. It was one of the most significant achievements in the campaign to abolish slavery throughout the world, more for its effect than for its actual legal weight.

In 1781 the crew of the over-capacity slaver ship Zong massacred an estimated 132 slaves by tossing them overboard; an additional ten slaves threw themselves overboard in defiance or despair and over sixty people had perished through neglect, injuries, disease and overcrowding.

The Zong’s crew had mis-navigated her course and underestimated water supplies; according to the maritime law notion of general average, cargo purposely jettisoned at sea to save the remainder was eligible for insurance compensation. It was reasoned that as the slaves were cargo, the ship’s owners would be entitled to the £30 a head compensation for their loss if thrown overboard: were the slaves to die on land or at sea of so-called “natural” causes, no compensation would be forthcoming.

The ship’s owners, a syndicate merchants based in Liverpool, filed their insurance claim; the insurers disputed it. In this first case the court found for the owners. The insurers appealed.

Sharp was visited on 19 March 1783 by Olaudah Equiano, a famous freed slave and later to be the author of a successful autobiography, who told him of the horrific events aboard the Zong. Sharp immediately became involved in the court case, facing his old adversary over slave trade matters, the Solicitor General for England and Wales, Mr. John Lee. Lee notoriously declared that “the case was the same as if asses had been thrown overboard”, and that a master could drown slaves without “a surmise of impropriety”.

The judge ruled that the Zong’s owners could not claim insurance on the slaves: the lack of sufficient water demonstrated that the cargo had been badly managed. However, no officers or crew were charged or prosecuted for the deliberate killing of the slaves, and Sharp’s attempts to mount a prosecution for murder never got off the ground.

Sharp was not completely alone at the beginning of the struggle: the Quakers, especially in America, were committed abolitionists. Sharp had a long and fruitful correspondence with Anthony Benezet, a Quaker abolitionist in Pennsylvania. However, the Quakers were a marginal group in England, and were debarred from standing for Parliament, and they had no doubt as to who should be the chairman of the new society they were founding, The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. On 22 May 1787, at the inaugural meeting of the Committee – nine Quakers and three Anglicans (who strengthened the committee’s likelihood of influencing Parliament) – Sharp’s position was unanimously agreed. In the 20 years of the society’s existence, during which Sharp was ever-present at Committee meetings, such was Sharp’s modesty that he would never take the chair, always contriving to arrive just after the meeting had started to avoid any chance of having to take the meeting. While the committee felt it sensible to concentrate on the slave trade, Sharp felt strongly that the target should be slavery itself. On this he was out-voted, but he worked tirelessly for the Society nevertheless.

When Sharp heard that the Act of Abolition had at last been passed by both Houses of Parliament and given Royal Assent on 25 March 1807, he fell to his knees and offered a prayer of thanksgiving. He was now 71, and had outlived almost all of the allies and opponents of his early campaigns. He was regarded as the grand old man of the abolition struggle, and although a driving force in its early days, his place had later been taken by others such as Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce and the Clapham Sect. Sharp however did not see the final abolition as he died on 6 July 1813

September 30, 2014

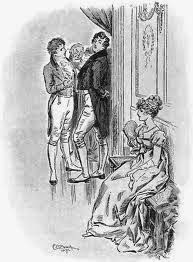

RAP is now looking for Cover and Interior artists-Can you draw like CE Brock?

Are you an Artist?

Now editing the final draft of another of our romance stories, we have started to lean to the idea that perhaps a professional artist might be better than our own renditions. Someone who can bring out the details and bring our stories alive.

If anyone knows of someone who would like to discuss designing a cover for RAP or the interiors (we think that a facing illustration at the start of every chapter like in the early part of the last century would be splendid), please get in contact with us.

In the immediate future we plan to launch a Kickstarter and wish to contract out the cover art and interior illustrations. Should we be funded in this project, you will be paid for your work immediately.

Our many works, one of the things we would like to see is having pen & ink or pencil illustrations at the beginning of each chapter. Can you draw like CE Brock? He did amazing work for the books and stories of Jane Austen in the early 1900s.

Regency Personalities Series-John Stuart 1st Marquess of Bute

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

John Stuart 1st Marquess of Bute

30 June 1744 – 16 November 1814

John Stuart

John Stuart 1st Marquess of Bute was the son of John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute and the former Mary Wortley Montagu, a granddaughter of the 1st Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull and great-granddaughter of the 1st Earl of Sandwich. He was educated at Winchester and Oxford University, and around 1757 he began to be tutored by the later famous Scottish philosopher Adam Ferguson.

Lord Mount Stuart was Tory Member of Parliament for Bossiney from 1766 to 1776. On 2 November 1775 he announced in the House of Commons his intention to introduce a bill to establish a militia in Scotland, and during the next few months James Boswell assisted in seeking support for the bill in Scotland. In March 1776 the bill was debated, but ultimately failed to pass. In 1776 Mount Stuart was elevated to the Peerage of Great Britain in his own right as Baron Cardiff, of Cardiff Castle in the County of Glamorgan. Though this title was also used, he continued to be sometimes to be known by his courtesy title of Lord Mount Stuart. In 1779 he was sworn of the Privy Council and was sent as an envoy to the court of Turin. He was ambassador to Spain in 1783. He held the sinecure of Auditor of the imprests from 1781 until the abolition of the office in 1785, upon which he was paid £7000 compensation. He succeeded his father in the earldom in 1792. In 1794 he was created Viscount Mountjoy, in the Isle of Wight, Earl of Windsor and Marquess of Bute. Lord Bute was inducted as a Fellow of the Royal Society on 12 December 1799.

Lord Bute married the Honourable Charlotte Hickman-Windsor, daughter of Herbert Hickman-Windsor, 2nd Viscount Windsor, on 12 November 1766. They had several children:

John Stuart, Lord Mount Stuart (25 September 1767 – 22 January 1794), whose son succeeded as 2nd Marquess

Lord Evelyn Stuart (1773–1842), a colonel in the army

Lady Charlotte Stuart (c. 1775 – 5 September 1847), married Sir William Homan, 1st Baronet

Lord Henry Stuart (7 June 1777 – 19 August 1809), father of Henry Villiers-Stuart, 1st Baron Stuart de Decies

Captain Lord William Stuart (18 November 1778 – 28 July 1814)

Rear-Admiral Lord George Stuart (1 March 1780 – 19 February 1841)

His first wife died on 28 January 1800. He married Frances Coutts, daughter of Thomas Coutts, on 17 September 1800. They had two children:

Lady Frances Stuart (d. 29 March 1859)

Lord Dudley Coutts Stuart (11 January 1803 – 17 November 1854)

His second wife outlived him, and died on 12 November 1832.

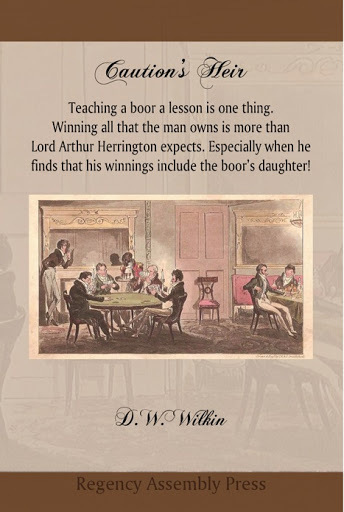

Caution’s Heir from Regency Assembly Press-Now available everywhere!

Caution’s Heir is now available at all our internet retailers and also in physical form as well

The Trade Paperback version is now available for purchase here @ $15.99 (but as of this writing, it looks like Amazon has still discounted it 10%)

Caution’s Heir is also available digitally for $4.99 @ the iBookstore, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo and Smashwords.

The image for the cover is a Cruikshank, A Game of Whist; Tom & Jerry among the ‘Swell Broad Coves.’ Tom and Jerry was a very popular series of stories at the time.

Teaching a boor a lesson is one thing.

Winning all that the man owns is more than Lord Arthur Herrington expects. Especially when he finds that his winnings include the boor’s daughter!

The Duke of Northampshire spent fortunes in his youth. The reality of which his son, Arthur the Earl of Daventry, learns all too well when sent off to school with nothing in his pocket. Learning to fill that pocket leads him on a road to frugality and his becoming a sober man of Town. A sober but very much respected member of the Ton.

Lady Louisa Booth did not have much hope for her father, known in the country for his profligate ways. Yet when the man inherited her gallant uncle’s title and wealth, she hoped he would reform. Alas, that was not to be the case.

When she learned everything was lost, including her beloved home, she made it her purpose to ensure that Lord Arthur was not indifferent to her plight. An unmarried young woman cast adrift in society without a protector. A role that Arthur never thought to be cast as. A role he had little idea if he could rise to such occasion. Yet would Louisa find Arthur to be that one true benefactor? Would Arthur make this obligation something more? Would a game of chance lead to love?

Today, the iBookstore is added, HERE

Get for your Kindle, Here

In Trade Paperback, Here

Digitally from Smashwords, Here

For your Sony Kobo, Here

Or for your Nook, Here

From our tale:

Chapter One

St. Oswald’s church was bleak, yet beautiful all in one breath. 13th century arches that soared a tad more than twenty feet above the nave provided a sense of grandeur, permanence and gravitas. These prevailed within, while the turret-topped tower without, once visible for miles around now vied with mature trees to gain the eye of passers-by.

On sunny days stain-glass windows, paid for by a Plantagenet Baron who lived four hundred years before and now only remembered because of this gift, cast charming rainbow beams across the inner sanctum. And on grey overcast days ghostly shadows danced along the aisle.

As per the custom of parish churches the first three pews were set-aside for the gentry. On this day the second pew, behind the seat reserved for the Marquess of Hroek, who hadn’t attended since the passing of his son and heir, was Louisa Booth his niece and her companion Mrs Bottomworth.

Mrs Bottomworth was a stocky matron on the good side of fifty. Barely on the good side of fifty. But one would not say that was an unfortunate thing for she wore her years well and kept her charge free of trouble. Mrs Bottomworth’s charge was an only child, who would still have been in the schoolroom excepting the fact of the death of her mother some years earlier. This had aged the girl quickly, and made her hostess to her father’s household. The Honourable Hector Booth, third son of the previous Marquess, maintained a modest house on his income of 300 pounds. That was quite a nice sum for just the man and one daughter, with but five servants. They lived in a small, two floor house with four rooms. It should be noted that this of course left two bedchambers that were not inhabited by family members. As the Honourable Mr Booth saved his excess pounds for certain small vices that confined themselves with drink and the occasional wager on a horse, these two rooms were seldom opened.

Mrs Bottomworth had thought to make use of one of the empty rooms when she took up her position, but the Honourable Hector Booth advised and instructed her to share his daughter’s room. For the last four years this is what she had done. When two such as these shared a room, it was natural that they would either become best of friends, or resent each other entirely. Happily the former occurred as Louisa was in need of a confidant to fill the void left in her mother’s absence, and Mrs Bottomworth had a similar void as her two daughters had grown and gone on to make their own lives.

The Honourable Mr Booth took little effort in concerning himself with such matters as he was ever about his brother’s house, or ensconced in a comfortable seat at either the local tavern or the Inn. If those locations had felt he was too warm for them, he would make a circuit of what friends and acquaintances he had in the county. The Honourable Mr Booth would spend an hour or two with a neighbour discussing dogs or hunters, neither of which he could afford to keep, though he did borrow a fine mount of his brother to ride to the hunt. The Marquess took little notice, having reduced his view of the world by degrees when first his beloved younger brother who was of an age between the surviving Honourable Mr Booth had perished shortly after the Marquess’ marriage. Their brother had fallen in the tropics of a fever. Then the Marquess had lost his second child, a little girl in her infancy, his wife but a few years after, and most recently his son and heir to the wars with Napoleon.

This caused the Honourable Mr Booth to be heir to Hroek, a situation that had occurred after he had lost his own wife. With that tragedy, Mr Booth had found more time to make friends with all sorts of new bottles, though not to a degree that it was considered remarkable beyond a polite word. Mr Booth was not a drunkard. He was confronting his grief with a sociability that was acceptable in the county.

Louisa, however, was cast further adrift. No father to turn to. No uncle who had been the patriarch of the family her entire life. And certainly now no feminine examples to follow but her companion and governess, Mrs Bottomworth. That Mrs Bottomworth was an excellent choice for the task was more due to acts of the Marquess, still able to think clearly at the time she was employed, than to the Honourable Mr Booth. Mr Booth was amenable to any suggestion of his elder brother for that man controlled his purse, and as Mr Booth was consumed with grief, while the Marquess had adapted to various causes of grief prior to the final straw of his heir’s death, the Marquess of Hroek clearly saw a solution to what was a problem.

Now in her pew, where once as a young girl she had been surrounded by her cousins, parents, uncles and aunt, she sat alone except for her best of friends. Louisa was full of life in her pew, her cheeks a shade of pink that contrasted with auburn hair, which glistened as sunlight that flowed though the coloured panes of glass touched it from beneath her bonnet. Blue eyes shown over a small straight nose, her teeth were straight, though two incisors were ever so slightly bigger than one would attribute to a gallery beauty painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

She was four inches taller than five feet, so rather tall for a young woman, but her genes bred true, and many a girl of the aristocracy was slightly taller than those women who were of humbler origins. Her back was straight and for an observant man, of which there were some few in the county, her figure might be discussed. The wrath though of her uncle the Marquess would not wish to be bourne should it be found out that her form had become a topic amongst the young men. Noteworthy though was that she had a figure that men thought inspiring enough to tempt that wrath, and think on it. A full bosom was high on her chest, below her heart shaped face. She was lean of form, though her hips flared just enough that one could see definition in her torso. Certainly a beauty Sir Thomas’ brushes would wish the honour to meet.

The vicar Mr Spotslet had at one time in his early days in the community, discussed the Sunday sermons with the Marquess. Mr Spotslet had enjoyed long discussions of theology, philosophy, natural history and the holy writ that were then thoughtfully couched in terms to be made accessible by the parish. The lassitude that had overtaken the Marquess had caused those interviews to become shortened and infrequent and as such the sermons suffered, as many were wont to note. There had been dialogues that Mr Spotslet had engaged in with the attendees of his masses. Now he seemed to have lost his way and delivered soliloquies.

This day Mr Spotslet indulged in a speech that talked to the vices of gambling. The local sports, of which the Honourable Mr Booth was an intimate, had raced their best through the village green the previous Wednesday for but a prize of one quid, and this small bet had caused pandemonium when Mrs McCaster had fallen in the street with her washing spread everywhere and trampled by the horses. Not much further along the path, Mr Smith the grocer’s delivery for the vicar himself was dropped by the boy and turned into detritus as that too was stampeded over. A natural choice for a sermon, yet only two of the culprits were in attendance this day. The rest had managed to find reasons to avoid the Mass.

Louisa squirmed a little in her seat the moment she realised that her father had been one of the men that the sermon was speaking of. Was she not the centre of everyone’s gaze at such a time? Her father having refused to attend for some years, and her uncle unable due to his illness. She was the representative of the much reduced family. Not only was it expected that the parish would look to her as the Booth of Hroek, but with her father’s actions called to the attentions of all, it was natural that they look at her again. This time in a light that did not reflect well on her father and she knew that she had no control over that at all.

Mrs Bottomworth, who might have been lightly resting her eyes, Louisa would credit her in such a generous way, came to tensing at the mention of the incident. Louisa did not want to bring her friend to full wakefulness, but Mrs Bottomworth realised what was occurring and the direction that the sermon was taking. Louisa’s companion took her hand and patted it reassuringly.

“Perhaps a social call on Lady Walker?” Mrs Bottomworth suggested as they walked back to the house after services. The house which sat just within the estate boundaries was four hundred feet off the main bridal way that led to Hroek Castle. A small road had been cleared from the gatehouse to the house that Mr Booth now maintained, and this the two women travelled.

Louisa generally appreciated visits such as this as she had gotten older, and certainly several of the adults in the neighbourhood showed a kindly interest in her education and the development of her social manners. “I think I shall go to the castle and read to my uncle.” A task that she had done each day of the last fortnight but one.

“We have not talked, but you and the Marquess had an interview with the doctors.” Mrs Bottomworth had tried to comfort her charge after that, but Louisa had waved her hand and gone to sit quietly under a yew tree that had a grand vista of the park leading to Hroek Castle.

“Uncle will be most lucky if he should be with us come Michaelmas.”

“That will be a sad day when we lose such a friend.” These were words of comfort. Mrs Bottomworth had been well encouraged in her charge by the Marquess but one could not say that they interacted greatly with one another. The Marquess ensured that his brother heeded the suggestions and advisements of Mrs Bottomworth as the Honourable Mr Booth left to his own devices would have kept his daughter in the nursery and would have forgotten to send a governess to provide her with instruction.

“Indeed, my uncle may not have been one of the great men of England, but he is well regarded in the county.” Often with that statement followed the next, “Warmly remembered is it when the Prince Regent came and stayed for a fortnight of sport and entertainment.” This had been many years before, and certainly before any of the tragedies beset the line of the Booths.

“Yes, I have heard it said with great earnestness. But come let us change your clothes and then we shall go up to the great house. I shall have Mallow fetch the gig so we may proceed all the more expeditiously.”

“That would be good, but we will have to use the dogcart. Father was to take the gig to see Sir Mark today, or so he said at breakfast.” Where Louisa knew he would drink the Baronet’s sherry for a couple hours before thinking to return, unless he was asked to stay for dinner.

September 29, 2014

Regency Personalities Series-Fanny Imlay

Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

Fanny Imlay

14 May 1794 – 9 October 1816

Fanny Imlay was the daughter of the British feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft and the American entrepreneur Gilbert Imlay. Both had moved to France during the French Revolution, Wollstonecraft to practise the principles laid out in her seminal work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and Imlay to engage in speculative business ventures. The two met and fell in love. At one point during Wollstonecraft and Imlay’s relationship, the couple could meet only at a tollbooth between Paris and Neuilly, and it was there that their daughter was conceived; Fanny was therefore, in Godwin’s words, a “barrier child”. Frances “Fanny” Imlay, Wollstonecraft’s first child, was born in Le Havre on 14 May 1794, or, as the birth certificate stated, on the 25th day of Floreal in the Second Year of the Republic, and named after Fanny Blood, her mother’s closest friend. Although Imlay never married Wollstonecraft, he registered her as his wife at the American consulate to protect her once Britain and France went to war in February 1793. Most people, including Wollstonecraft’s sisters, assumed they were married—and thus, by extension, that Fanny was legitimate—and she was registered as such in France.

Initially, the couple’s life together was idyllic. Wollstonecraft playfully wrote to one friend: “My little Girl begins to suck so manfully that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the R[igh]ts of Woman”. Imlay soon tired of Wollstonecraft and domestic life and left her for long periods of time. Her letters to him are full of needy expostulations, explained by most critics as the expressions of a deeply depressed woman but by some as a result of her circumstances—alone with an infant in the middle of the French Revolution.

Wollstonecraft returned to London in April 1795, seeking Imlay, but he rejected her; the next month she attempted to commit suicide, but he saved her life (it is unclear how). In a last attempt to win him back, she embarked upon a hazardous trip to Scandinavia from June to September 1795, with only her one-year-old daughter and a maid, in order to conduct some business for him. Wollstonecraft’s journey was daunting not only because she was travelling to what some considered a nearly uncivilized region during a time of war, but also because she was travelling without a male escort. When she returned to England and realized that her relationship with Imlay was over, she attempted suicide a second time. She went out on a rainy night, walked around to soak her clothes, and then jumped into the River Thames, where a stranger rescued her.

Using her diaries and letters from her journey to Scandinavia, Wollstonecraft wrote a rumination on her travels and her relationship—Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796)—in which, among other things, she celebrated motherhood. Her maternal connection to her daughter prompted her to reflect on a woman’s place in the world:

You know that as a female I am particularly attached to her—I feel more than a mother’s fondness and anxiety, when I reflect on the dependent and oppressed state of her sex. I dread lest she should be forced to sacrifice her heart to her principles, or principles to her heart. With trembling hand I shall cultivate sensibility, and cherish delicacy of sentiment, lest, whilst I lend fresh blushes to the rose, I sharpen the thorns that will wound the breast I would fain guard—I dread to unfold her mind, lest it should render her unfit for the world she is to inhabit—Hapless woman! what a fate is thine!

Wollstonecraft lavished love and attention on her daughter. She began two books, drawn from her own experience, related to Fanny’s care: a parenting manual entitled “Letters on the Management of Infants” and a reading primer entitled “Lessons”. In one section of “Lessons”, she describes weaning:

When you were hungry, you began to cry, because you could not speak. You were seven months without teeth, always sucking. But after you got one, you began to gnaw a crust of bread. It was not long before another came pop. At ten months you had four pretty white teeth, and you used to bite me. Poor mamma! Still I did not cry, because I am not a child, but you hurt me very much. So I said to papa, it is time the little girl should eat. She is not naughty, yet she hurts me. I have given her a crust of bread, and I must look for some other milk.

In 1797, Wollstonecraft fell in love with and married the philosopher William Godwin (she had become pregnant with his child). Godwin grew to love Fanny during his affair with Wollstonecraft; he brought her back a mug from Josiah Wedgwood’s pottery factory with an “F” on it that delighted both mother and daughter. Wollstonecraft died in September of the same year, from complications giving birth to Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, who survived. Three-year-old Fanny, who had been scarred from smallpox, was unofficially adopted by her stepfather and given the name of Godwin. Her copy of Wollstonecraft’s only completed children’s book, Original Stories from Real Life (1788), has the initials “F. G.” written in large print in it. According to the dominant interpretation of Godwin’s diary, it was not until Fanny turned twelve that she was informed in an important conversation with Godwin that he was not her natural father.

After Wollstonecraft’s death, Godwin and Joseph Johnson, Wollstonecraft’s publisher and close friend, contacted Fanny’s father, but he was uninterested in raising his child. (Neither Wollstonecraft nor her daughter ever saw Gilbert Imlay after 1796.) Wollstonecraft’s two sisters, Eliza Bishop and Everina Wollstonecraft, Fanny’s only two living female relatives, were anxious to care for her; Godwin, disliking them, turned down their offer. Several times throughout Fanny’s childhood Wollstonecraft’s sisters asked Godwin to allow them to raise their niece and each time he refused. Godwin himself did not seem particularly ready for parenthood and he now had two small children to raise and no steady source of income. However, he was determined to care for them. During these early years of Fanny’s life, Joseph Johnson served as an “unofficial trustee” for her as he had occasionally for her mother. He even willed her £200, but Godwin owed Johnson so much money upon his death in 1809 that Johnson’s heirs demanded Godwin pay the money back as part of his arrears.

Although Godwin was fond of his children, he was, in many ways, ill-equipped to care for them. As Todd explains, he was constantly annoyed by their noise, demanding silence while he worked. However, when he took a trip to Dublin to visit Wollstonecraft’s sisters, he missed the girls immensely and wrote to them frequently.

On 21 December 1801, when Fanny was seven, Godwin married Mary Jane Clairmont, a neighbour with two children of her own: three-year-old Claire and six-year-old Charles. She had never been married and was looking, like Godwin, for financial stability. Although Clairmont was well-educated and well-travelled, most of Godwin’s friends despised her, finding her vulgar and dishonest. They were astonished that Godwin could replace Mary Wollstonecraft with her. Fanny and her half-sister Mary disliked their stepmother and complained that she preferred her own children to them. On 28 March 1803, baby William was born to the couple.

Although Godwin admired Wollstonecraft’s writings, he did not agree with her that women should receive the same education as men. Therefore, he occasionally read to Fanny and Mary from Sarah Trimmer’s Fabulous Histories (1786) and Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s Lessons for Children (1778–79), but, according to Todd, he did not take great pains with their educations and disregarded the books Wollstonecraft had written for Fanny. William St Clair, in his biography of the Godwins and the Shelleys, argues that Godwin and Wollstonecraft spoke extensively about the education they wanted for their children and that Godwin’s writings in The Enquirer reflect these discussions. He contends that after Wollstonecraft’s death Godwin wrote to a former pupil to whom she had been close, now Lady Mountcashell, asking her advice on how to raise and educate his daughters. In her biography of Mary Shelley, Miranda Seymour agrees with St Clair, arguing that “everything we know about his daughter’s [Mary's and presumably Fanny's] early years suggests that she was being taught in a way of which her mother would have approved”, pointing out that she had a governess, a tutor, a French-speaking stepmother, and a father who wrote children’s books whose drafts he read to his own first. It was the new Mrs Godwin who was primarily responsible for the education given to the girls, but she taught her own daughter more, including French. Fanny received no formal education after her stepfather’s marriage. Yet, the adult Imlay is described by C. Kegan Paul, one of Godwin’s earliest biographers, as “well educated, sprightly, clever, a good letter-writer, and an excellent domestic manager”. Fanny excelled in drawing and was taught music. Despite Godwin’s atheism, all of the children were taken to an Anglican church.

The Godwins were constantly in debt, so Godwin returned to writing to support the family. He and his wife started a Juvenile Library for which he wrote children’s books. In 1807, when Fanny was 13, they moved from the Polygon, where Godwin had lived with Wollstonecraft, to 41 Skinner Street, near Clerkenwell, in the city’s bookselling district. This took the family away from the fresh country air and into the dirty, smelly, inner streets of London. Although initially successful, the business gradually failed. The Godwins also continued to borrow more money than they could afford from generous friends such as publisher Joseph Johnson and Godwin devotee Francis Place.

As Fanny Imlay grew up, her father increasingly relied on her to placate tradespeople who demanded bills be paid and to solicit money from men such as Place. According to Todd and Seymour, Imlay believed in Godwin’s theory that great thinkers and artists should be supported by patrons and she believed Godwin to be both a great novelist and a great philosopher. Throughout her life, she wrote letters asking Place and others for money to support Godwin’s “genius” and she helped run the household so that he could work.

Godwin, never one to mince words, wrote about the differences he perceived between his two daughters:

My own daughter [Mary] is considerably superior in capacity to the one her mother had before. Fanny, the eldest, is of a quiet, modest, unshowy disposition, somewhat given to indolence, which is her greatest fault, but sober, observing, peculiarly clear and distinct in the faculty of memory, and disposed to exercise her own thoughts and follow her own judgment. Mary, my daughter, is the reverse of her in many particulars. She is singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire for knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes is almost invincible. My own daughter is, I believe, very pretty; Fanny is by no means handsome, but in general prepossessing.

The intellectual world of the girls was widened by their exposure to the literary and political circles in which Godwin moved. For example, during former American vice-president Aaron Burr’s self-imposed exile from the United States after his acquittal on treason charges, he often spent time with the Godwins. He greatly admired the works of Wollstonecraft and had educated his daughter according to the precepts of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. He was anxious to meet the daughters of the woman he revered and referred to Fanny, Mary, and Claire as “goddesses”. He spent most of his time talking with Imlay about political and educational topics. Burr was impressed by the Lancastrian teaching method and took Fanny to see a model school in 1811.

It was not Burr, but the Romantic poet and writer Percy Bysshe Shelley who had the greatest impact on Imlay and her sisters’ lives. Impressed by Godwin’s Political Justice, Shelley wrote to him and the two started corresponding. In 1812, Shelley asked if Imlay, then 18 and the daughter of one of his heroes, Mary Wollstonecraft, could come live with him, his new wife, and her sister. Having never actually met Shelley and being sceptical of his motivations (Shelley had eloped to marry his wife, Harriet), Godwin refused. When Shelley finally came to visit the Godwins, all three girls were enamoured with him, particularly Imlay. Both Shelley and Imlay were interested in discussing radical politics; for example, Shelley liked to act as if class were irrelevant, but she argued that it was significant in daily affairs.

In 1814, Shelley spent a considerable amount of time at the Godwins’ and he and Imlay may have fallen in love. Later, Claire Clairmont claimed that they had been. Imlay was sent to Wales in May of that year; Todd speculates that Godwin was trying to separate her from Shelley while Seymour hints that Mrs Godwin was trying to improve her despondent mood. Meanwhile, the Godwin household became even more uncomfortable as Godwin sank further into debt and as relations between Mary and her stepmother became increasingly hostile. Mary Godwin consoled herself with Shelley and the two started a passionate love affair. When Shelley declared to Godwin that the two were in love, Godwin exploded in anger. However, he needed the money that Shelley, as an aristocrat, could and was willing to provide. Frustrated with the entire situation, Mary Godwin, Shelley, and Claire Clairmont ran off to Europe together on 28 June 1814. Godwin hurriedly summoned Imlay home from Wales to help him handle the situation. Her stepmother wrote that Imlay’s “emotion was deep when she heard of the sad fate of the two girls; she cannot get over it”. In the middle of this disaster, one of Godwin’s protégés killed himself, and young William Godwin ran away from home and was missing for two days. When news of the girls’ escapade became public, Godwin was pilloried in the press. Life in the Godwin household became increasingly strained.

When Mary Godwin, Claire Clairmont, and Shelley returned from the Continent in September 1814, they took a house together in London, enraging Godwin still further. Imlay felt pulled between the two households: she felt loyal both to her sisters and to her father. Both despised her decision not to choose a side in the family drama. As Seymour explains, Imlay was in a difficult position: the Godwin household felt Shelley was a dangerous influence and the Shelley household ridiculed her fear of violating social conventions. Also, her aunts were considering her for a teaching position at this time, but were reluctant because of Godwin’s shocking Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798). Seymour writes, the “few timid visits Fanny made to see Mary and [Claire] in London were acts of great courage; she got little thanks for them”. Although instructed by Godwin not to speak to Shelley and her sisters, Imlay warned them of creditors who knew of Shelley’s return (he also was in debt). Her attempts to persuade Clairmont to return to the Godwins’ convinced Shelley that she was of Godwin’s party and he began to distrust her. Imlay was also still responsible for soliciting money from Shelley in order to repay her father’s debts; despite Shelley’s essential elopement with two of his daughters, Godwin agreed to accept £1,200 from Shelley. When Mary Godwin gave birth to a daughter in February 1815, she immediately sent for Imlay, particularly as both she and the infant were ill. Godwin chastised Imlay for disobeying his orders not to see her half-sister and her misery increased. After the death of the child, Imlay paid more frequent visits to the couple.

Soon after, Clairmont became a lover of the Romantic poet Lord Byron, and Mary Godwin and Shelley had a second child on 24 January 1816, who was named William after Godwin. In February, Imlay went to visit the Shelleys, who had settled in Bishopsgate. Godwin’s debts continued to mount, and while he demanded money from Shelley, Godwin still refused to see either him or his daughter. At this time, Charles Clairmont (Imlay’s step-brother), frustrated with the tension in the Godwin household, left for France and refused to help the family any further. At around the same time, Claire Clairmont, Mary Godwin, and Shelley left for the Continent, seeking Byron. Godwin was aghast. He relied on Shelley’s money, and the stain on his family’s reputation only increased when the public learned that the group had left to join the rakish Byron.

Amidst all of this family turmoil, Imlay still found time to ponder larger social issues. The utopian socialist Robert Owen came to visit Godwin in the summer of 1816 and he and Imlay discussed the plight of the working poor in Britain. She agreed with many of Owen’s proposals, but not all of them. She decided, in the end, that his utopian scheme was too “romantic”, because it depended heavily on the goodwill of the rich to sacrifice their wealth. That same summer, George Blood—the brother of Fanny Imlay’s namesake—came to meet her for the first time and told her stories of her mother. After this meeting she wrote to Mary Godwin and Shelley: “I have determined never to live to be a disgrace to such a mother… I have found that if I will endeavour to overcome my faults I shall find being’s [sic] to love and esteem me” .

Before Mary Godwin, Clairmont, and Shelley had left for the Continent, Imlay and Mary had had a major argument and no chance to come to a reconciliation. Imlay attempted in her letters to Mary to smooth over the relationship, but her sense of loneliness and isolation in London are palpable. She wrote to Mary of “the dreadful state of mind I generally labour under & which I in vain endeavour to get rid of”. Many scholars attribute Imlay’s increasing unhappiness to Mrs Godwin’s hostility towards her. Kegan, and others, contend that Imlay was subject to the same “extreme depression to which her mother had been subject, and which marked other members of the Wollstonecraft family”. Wandering amongst the mountains of Switzerland, frustrated with her relationship with Shelley, and engrossed by the writing of Frankenstein, her sister was unsympathetic.

The group returned from the Continent, with a pregnant Clairmont, and settled in Bath (to protect her reputation, they attempted to hide the pregnancy). Imlay saw Percy twice in September 1816; according to Todd’s interpretation of Fanny’s letters, Fanny had earlier tried to solicit an invitation to join the group in Europe and she repeated these appeals when she saw Percy in London. Todd believes that Imlay begged to be allowed to stay with them because life in Godwin’s house was unbearable, with the constant financial worries and Mrs Godwin’s insistent haranguing, and that Percy refused, concerned that anyone learn about Clairmont’s condition, least of all someone he believed might inform Godwin (Shelley was being sued by his wife and was worried about his own reputation). After Percy left, Todd explains that Imlay wrote to Mary “to make clear again her longing to be rescued”.

In early October 1816, Imlay left Godwin’s house in London and committed suicide on 9 October by taking an overdose of laudanum at an inn in Swansea, Wales; she was 22. The details surrounding her death and her motivations are disputed. Most of the letters regarding the incident were destroyed or are missing. In his 1965 article “Fanny Godwin’s Suicide Re-examined”, B. R. Pollin lays out the major theories that had been put forward regarding her suicide and which continue to be used today:

Imlay had just learned of her illegitimate birth.

Mrs Godwin became more cruel to Imlay after Mary Godwin and Claire Clairmont ran off with Percy Shelley.

Imlay had been refused a position at her aunts’ school in Ireland.

Imlay was depressive, and her condition was aggravated by the state of the Godwin household.

Imlay was in love with Percy Shelley and distraught that Mary and he had fallen in love.

Pollin dismisses the first of these, as have most later biographers, arguing that Imlay had access to her mother’s writings and Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman which openly discuss the circumstances of her birth. Imlay herself even makes this distinction in letters to her half-sister Mary Godwin.

Pollin is also sceptical of the second explanation, pointing to Imlay’s letter to Mary of 3 October 1816 in which she defended her step-mother: “Mrs. Godwin would never do either of you a deliberate injury. Mamma and I are not great friends, but always alive to her virtues, I am anxious to defend her from a charge so foreign to her character.”

Pollin finds no evidence that Imlay had been refused a position at her aunts’ school, only that such a scheme may have been “in contemplation”, as Godwin later wrote, although Seymour grants this explanation some plausibility. St Clair claims that Imlay was on her way to join her maternal aunts in Ireland when she decided to commit suicide. He believes that it was to be a probationary visit, to see if she could be a teacher in their school. Godwin’s modern biographer, Richard Holmes, dismisses this story.

In his survey of the letters of the Godwins and the Shelleys, Pollin comes to the conclusion that Imlay was not depressive. She is frequently described as happy and looking toward the future and describes herself this way. The mentions of melancholia and sadness are specific and related to particular events and illness. Richard Holmes, in his biography of Percy Shelley, argues that “her agonizing and loveless suspension between the Godwin and Shelley households was clearly the root circumstance” of her suicide. Locke argues that “most probably because she could absorb no more of the miseries of Skinner Street, her father’s inability to pay his debts or write his books, her mother’s unending irritability and spitefulness”, all of which she blamed on herself, she committed suicide.

Pollin largely agrees with Todd, speculating that Imlay saw Percy Shelley in Bath and he “somehow failed her”, causing her to commit suicide. Seymour and others speculate that Shelley’s only failure was to live up to his financial promises to Godwin and it was this that helped push Imlay over the edge; she was convinced, like her father, “that the worthy have an absolute right to be supported by those who have the worth to give”. Todd, on the other hand, agrees with Pollin and speculates that Imlay went to see Mary Godwin and Shelley. Todd argues that Imlay had affection for Shelley and felt that his home was her only haven. Relying on scraps of poetry that Shelley may have written after Imlay’s death, Todd concludes that Shelley saw her in Bath and rejected her pleas because he needed to protect Claire’s reputation as well as his own at this time. Todd also notes that Imlay had worn her mother’s stays, which were embroidered with the initials “M.W.”, and the nicest clothes she owned. She had adorned herself with a Swiss gold watch sent to her from Geneva by the Shelleys and a necklace, in order to make a good impression. After Shelley rejected her, Todd concludes, Imlay decided to commit suicide.

On the night of 9 October, Imlay checked into the Mackworth Arms Inn in Swansea and instructed the chambermaid not to disturb her. The same night Mary Godwin, staying in Bath with Shelley, received a letter Imlay had mailed earlier from Bristol. Her father in London also received a letter. The alarming nature of the letters prompted both Godwin and Shelley to set out for Bristol at once (although they travelled separately). By the time they tracked her to Swansea on 11 October, they were too late. Imlay was found dead in her room on 10 October, having taken a fatal dose of laudanum.

RAP’s has Beggars Can’t Be Choosier

One of the our most recent Regency Romances.

Beggars has won the prestigious Romance Reviews Magazine Award for Outstanding Historical Romance:

It is available for sale and I hope that you will take the opportunity to order your copy.

For yourself or as a gift. It is now available in a variety of formats. For $3.99 you can get this Regency Romance for your eReader. A little more as an actual physical book.

When a fortune purchases a title, love shall never flourish, for a heart that is bought, can never be won.

The Earl of Aftlake has struggled since coming into his inheritance. Terrible decisions by his father has left him with an income of only 100 pounds a year. For a Peer, living on such a sum is near impossible. Into his life comes the charming and beautiful Katherine Chandler. She has a fortune her father made in the India trade.

Together, a title and a fortune can be a thing that can achieve great things for all of England. Together the two can start a family and restore the Aftlake fortunes. Together they form an alliance.

But a partnership of this nature is not one of love. And terms of the partnership will allow both to one day seek a love that they both deserve for all that they do. But will Brian Forbes Pangentier find the loves he desires or the love he deserves?

And Katherine, now Countess Aftlake, will she learn to appreciate the difference between happiness and wealth? Can love and the admiration of the TON combine or are the two mutually exclusive?

Purchase here:Amazon Kindle, Barnes and Noble Nook, Kobo, Smashwords, iBooks, & Trade Paperback

Feedback

If you have any commentary, thoughts, ideas about the book (especially if you buy it, read it and like it ;-) then we would love to hear from you.

[image error] [image error]

September 28, 2014

RAP is now looking for Cover and Interior artists-Can you draw like CE Brock?

Are you an Artist?

Now editing the final draft of another of our romance stories, we have started to lean to the idea that perhaps a professional artist might be better than our own renditions. Someone who can bring out the details and bring our stories alive.

If anyone knows of someone who would like to discuss designing a cover for RAP or the interiors (we think that a facing illustration at the start of every chapter like in the early part of the last century would be splendid), please get in contact with us.

In the immediate future we plan to launch a Kickstarter and wish to contract out the cover art and interior illustrations. Should we be funded in this project, you will be paid for your work immediately.

Our many works, one of the things we would like to see is having pen & ink or pencil illustrations at the beginning of each chapter. Can you draw like CE Brock? He did amazing work for the books and stories of Jane Austen in the early 1900s.