Max Gladstone's Blog, page 12

March 26, 2014

The Tractor Story from ICFA. Also, Vericon fun!

Greetings Earthling carbon units. I am a digitized uploaded echo of Max’s consciousness, which is still in traction after ICFA and Vericon. I have been instructed to inform you all that he had an excellent time, and / though he is still somewhat unhinged as a result of sleep deprivation. Do not fear, however: he endures, recovers, and grows stronger through a combination of espresso, dark magic, exercise, and metal.

Current exhaustion is irrelevant, however, compared to the general excellence of guerilla poolside readings, hot tub luxuriation, good food with excellent people, wonderful readings, far too many cocktails, books and signings at ICFA, Smallworld (with Saladin Ahmed and ML Brennan and the Durdands, & Pat Rothfuss looking on; Saladin crushed us all with a vicious combination of Stout Skeletons and Merchant Humans), and some of the best panels it’s ever been my / meat-Max’s pleasure to participate in. Different in many ways, Vericon and ICFA were amazing, and it was a pleasure to attend both.

Hugo Reminder

If you’re voting for the Hugos this year, we only have a few days left so I figure it’s fair to sum up my eligibility: I’m still eligible for the John W. Campbell Best New Writer award this year; Two Serpents Rise is eligible for the Best Novel category, and Drona’s Death is eligible for Short Story. If you’re not voting for the Hugos this year, let me offer you some non-voting reminders so you can get in the spirit: the discursions in Hugo’s Les Miserables are not as irrelevant as they seem at first glance, and if you liked the musical you really should read the book sometime. Also, an early film version of The Man Who Laughs was a primary inspiration for the Joker’s character design. Anyway! Enough Hugo. On to Tractors.

The Tractor Story

The International Conference on the Fantastic in Art this year shared convention space with a John Deere brand meeting, and of course, being writers, we had to do something with that in true Heian garden-party fashion. Evidence is hazy on who proposed the initial idea, but after a few drinks poolside a number of us including Fran Wilde, Ilana Teitelbaum Reichert, and Emily Jiang embarked on a flash fiction contest with a John Deere theme. Ellen Klages agreed to judge. The prize: a John Deere hat. And so without further ado, a brief adult language warning, and many apologies (among them to Kenny Chesney), allow me to present the contest winner: my story, Sam Ogilvy’s Lament.

Sam Ogilvy’s Lament

by Max Gladstone

She thinks my tractor’s sexy.

And she don’t even think it for the right reasons. A kind of attraction I’d understand: he’s a sharp John Deere chassis with top-shelf Yoshida trinary brain and 16 nanometer mag field resolution to guide its little critters as they unsalt the chem-fucked earth. Cleans and plants a field ten times faster than the A-230. One season with him and some of Grampa’s old high pasture what hasn’t sprouted shrub in years can carry a crop to term. Keep him away from over-fucked soil and he’ll run forever. Apple candy green, with shiny canola yellow stripes and highlights. He is some machine, worth every drop of sweat it’ll take to earn him off.

But that ain’t what gets her. I mean, she respects him—her folks’ farm’s just two miles over, and she knows from good equipment. When I got him, at first I thought that’s all it was. She walked over that morning, fresh and full in Daisy Dukes and sweating from the sun, and looked all the way up to me on the back of that John Deere and asked for a ride. I asked him, and he said fine, so I had her climb on up and she straddled him and held the touch ‘trodes and I said take him for a spin, and climbed down to watch them roll to the old mended pasture fence and back, her whooping high and long as the sun rose.

And watching her holler with her head back and hair streaming I had some unchristian thoughts, I tell you.

She thanked me. I said she could come see him any time. She smiled and said she’d take me up on that.

“Sam,” he said once she was gone and we got back to work, “your friend is a fascinating person.”

“Irene?” I was happy about it then. I thought, she’ll be by regular to see the tractor and who knows what might happen. “Yup.”

But she took to coming by in the evenings long after work, just settin’ in the barn talking to him, crosslegged in overalls on the floor by his big wheels. I snuck up on them once to listen. “A cookie?” she asked.

“A madelene is a kind of cookie, from the writer’s childhood. Our parents would have used chocolate chip. Of course there’s no chocolate now.”

I tried to joke with her about it one night, but she gave me that angry frown makes her lower lip stick out like a ledge. “Fred’s third generation hipster. His folks were trapped in Brooklyn after the Big Seal. He ain’t ever seen proper stars but through those camera eyes, and when they plug him out of the Turk he goes home to a three-room apartment he shares with fourteen guys all high on federal dope. We never had to live like that and it wouldn’t hurt you to show some human feeling, Samuel Ogilvy.”

“Don’t see where his books come into it, is all. They got us into this shit in the first place. He should want to learn from us ‘stead of thinking he knows best while he flies the bugs and fixes the soil.”

“Not all those books were the problem. Some of them, if anyone had listened, maybe we wouldn’t be in this mess. And Fred is learning from you. You know he started a rooftop garden? They’re getting tomatoes off that. Real ones. Fruit of their own hands, not from Turk-for-Food or anything.”

“Well color me fucking impressed” was I guess the wrong thing to say, because when I did she looked at me like I’d grown a third eye and then she stormed off.

I felt bad about that. Fred and I didn’t talk for a few days. Thursday night, though, the stars were bright and brilliant out the window, a high clear sky with the Milky Way as real as a dusty road. And the pair of them stood out in the back field: him huge and still green even in the starlight, and her with one hand tender on his wheel.

I went to join them.

The night was cool and the kind of dark that has light in it. At first I thought she must have moved around to his other side, because I couldn’t see her.

Then I saw something move on top of him.

I heard the generator’s whine, and a soft moan I’d hoped to hear elsewhere. Human body ain’t got much metal in it—but enough for a 16-nanometer resolution mag field to touch lightly. Or less than lightly.

She didn’t holler. She was trying to keep quiet. After a while, she laughed like falling rain.

I left.

But I’ve got to thinking: there’s this old field up past Grampa’s we own but haven’t plowed in twenty years on account of the soil’s too chem- and critter-fucked. Try to work it and I’ll break the bugs the tractor uses, brick the thing and end up stuck with a bad loan and a long wait for my next. Have to go back to the old A-230. But the A-230 don’t read books, and hell, without that new John Deere maybe Irene and I could work.

Besides, the A-230′s that same pretty shade of green.

March 19, 2014

Interviews, The Poker Analogy, ICFA, Vericon, and TV Tropes!

Lots of stuff for you all this week!

To start off—the excellent Mur Lafferty hosted me on her podcast, I Should be Writing. Thanks, Mur! The interview is here, and is great. Alas, though, it was cut off right at the end. Basically the only thing missing is a longwinded analogy I was about to launch into about ideas, poker, and writing. Twitter-person @tamahome02000 asked for the end of the analogy, so here it goes.

The Poker Analogy

Ideas are like the hole cards in poker—in Texas Holdem you’re dealt two cards in the hole, your private hand no one else can see, and five cards to the board, which everyone else can see. All players try to construct the highest hand of five cards from any combination of their hole and the board. In this analogy, the “board” is all the aspects of writing to which everyone has access: the current state of the English language, the publishing market, trends in your chosen genre, whatever.

So you think, ah-hah, to win at writing I just need THE BEST IDEA POSSIBLE. I will never commit to a board unless I am holding the nuts. One of the funny things about Holdem and writing alike, though, is that the board develops over time—you first bet without seeing any board cards. After the first round of betting, three of the five total board cards are revealed. After another round of betting, you see the fourth, and after the third round, if anyone’s still playing, you see the fifth. The best idea you could possibly have in the first round—pair of aces, say, the most valuable hand you can build with only two cards—might not intersect at all with the board. Your buddy went in with Ace-8, but the flop gives her two more eights and there’s nary an ace to be seen—and hell, even if you do crack an ace on the turn, your three of a kind will lose to her eights full of aces.

Because in writing, as in poker, success doesn’t result from an idea (hole) or circumstance (board). You need both of these, sure—but success results from play. Let’s go back to our Ace-eight example earlier. You can’t see your buddy’s hand. You play super conservatively—you never commit unless you have, let’s say, pair of kings or better. All night long. Your buddy, you know, plays a little loose—and plays a wider range of hands, among them Ace-eight. She sees the flop with you, and it’s, say, 4-8-8. She bets conservatively; you commit more, thinking she has a pair of kings, and she re-raises, and all of a sudden you start thinking, shit, she has the eights. But does she really?

And so on.

As poker players go I’m something of a sieve through which money flows, so let me cut to the point: you can always be outplayed, even if you have the best hole cards in the game. Which is just to say, the better a player you are, more you can do with the cards you’re dealt.

Which is not to say that hand composition doesn’t matter! Good players aren’t afraid to fold, as Kenny Rogers reminds us. But they’re not afraid to play, either, and where some people might see garbage, a good player sees opportunity.

And the only way you become a better player, of course, is by playing. So if you’re sitting at the keyboard thinking, gosh, if I write this idea down then it’s gone and I will never have any more ideas ever ever ever, well… you’re probably shooting yourself in the foot. The more you hesitate, the less progress you make on your own art.

Look for the right ideas, sure. Sometimes the perfect idea hits you like a bolt from the heavens. Sometimes it doesn’t don’t. A good writer can do something awesome in both cases.

Oh yeah and success.

I have very little idea what I mean by ‘success’ above. I don’t mean making money. (F. Scott Fitzgerald died poor and drunk.) I don’t mean being published by the Big However Many We’re Saying They Are These Days. (Contemporary equivalents of the Big However wouldn’t publish Lady Chatterly’s Lover, Ulysses, or Howl. Virginia Woolf self-published most of her work. Though don’t think that invalidates Publishing, either—it worked for Faulkner, Hemmingway, Steinbeck, Edith Wharton and Ralph Ellison. Pace Frank Baum, there are many roads to the City, though see above as to the question of whether any of these roads is paved with golden bricks.) I don’t even mean showing anyone your work, though I caution folks against taking the Emily Dickinson route. I might mean writing things worth reading; knowing you’ve made something that scares you, or makes you proud, or sends a message, or fights a power, or tells a truth, or mourns what’s lost. I might mean being able to write things worth writing. Though we can’t stop there: we’re in Tautology Country!

ICFA

As you read this, I’m traveling to the airport to fly south for the International Conference on the Fantastic Arts. I don’t think I’m on any programming, but if you’re there, say hi! I plan on bringing one suit and an assortment of brightly-colored short-sleeved shirts, because new spring in Boston is about as spring-y as new spring in the Borderlands (which makes Canada the Blight I guess?) and I won’t get to wear anything flower-printed in my hometown for another month at least. I’ll be returning from ICFA on Friday, though, so I can be a guest at….

Vericon!

Vericon is Harvard’s student-run convention, and looks to be crazy this year—the con isn’t terribly large, but they have an all-star cast of literary guests. Here’s my schedule, though you really should check out their website for more info.

Saturday

10am – 11am – Selling Your First Novel – M.L Brennan, Luke Scull, Saladin Ahmed, Max Gladstone – Writing it is difficult, and when it’s done that’s when the trouble really starts. How do you sell your first novel in today’s market? – Lead by Shuvom Ghose (Sever 113)

11 am – 12:30pm Panel on Interactive Media – Max Gladstone, Luke Scull, Patrick Rothfuss – So, this panel is geared towards discussing the challenges and advantages of story-writing for media other than the printed word. How does having to deal with player interactivity affect story? How do you tell a story in conjunction with music and visuals? Those and similar questions will be the focus of this panel. – Lead by Ore Babarinsa (Sever 113)

BOOK SIGNING — You should all come to my signing of course, but some other people are signing whose presence just might be worth your attention, and by just might be worth your attention I mean absolutely come to this signing oh my god look at these people. All of these events are at Harvard Book Store in Harvard Square!

Patrick Rothfuss : 1pm – 2pm

Jo Walton & Scott Lynch : 1:45pm – 2:15pm

M.L. Brennan, Saladin Ahmed & Max Gladstone : 2:30pm – 3:00pm

Luke Scull & Greer Gilman : 3:15 – 3:45 pm

1pm – 2pm – Seen One Elf, Seen ‘em All – Saladin Ahmed, Scott Lynch, Max Gladstone, Shira Lipkin

How do you get away from codmedieval Europe fantasyland? There’s am exciting recent trend towards more original kinds of fantasy worlds, ones drawing on other cultures. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this new approach? – Lead by Carl Engle-Laird (Sever 113)

3:30pm – 4:30pm – Worldbuilding Panel – Patrick Rothfuss, Saladin Ahmed, Scott Lynch, and Max Gladstone

This panel focuses on crafting a setting, and how one actually builds the story. Further, it’ll also touch on influences, both literary and culture, for your writing, as well as what you think goes into your work. Lastly, It’s also an opportunity for guests to ask you about details of your worlds, and discuss the things off the beaten path in your works. – Lead by Carl Engle-Laird

(Sever 113)

8pm – 10pm – Milk and Cookies -Lowell Lecture Hall – This is totally optional, so if you’re exhausted by this point, feel free to return to your hotels and rest. That being said, if you want to do any sort of readings of your own work, or even just share some your own personal favorite works, please participate! To explain the concept of Milk and Cookies, it’s a HRSFA/HRSFAN tradition where we all get together and share short stories in a circle (or in the case of Vericon, several circles), while sharing snacks, particularly the eponymous milk and cookies.

TV Tropes!

And, because I have no regard for your personal productivity—turns out there’s a Two Serpents Rise page over at TV Tropes! *sniff* I’m so happy….

Happy, and as you may have guessed from the above, busy. That’s all for this week. Have a great few days, see you this weekend maybe, and catch you on the flip side!

March 12, 2014

Deus Ex Savings Time

[Advance warning: this post may involve nostalgia.]

I never realized how weird Daylight Savings Time was until I returned to it.

The People’s Republic of China does not have such a conceit. In fact the PRC doesn’t go in for much American-model timefoolery at all: no time zones either, and a land mass comparable to the US, makes for 2pm solar noon over Lhasa, and the occasional 9 am sunrise.

I lived in rural Anhui for a couple years after college, which I’ve mentioned before. If you chase back into the darkest recesses of this blog you will see some travel notes from those days. This isn’t the post where I talk about the cultural experience of living abroad, though that’s a rich topic—I made friends, improved my Chinese, saw my world from outside itself, taught cool students, ran past water buffalo in the rain, learned taiji, climbed around ancient abandoned towers, drank tea in temples, learned to cook and to play mah jiang and work through local politics, etc. etc. etc. There’s so much to write about all that, it’s hard to fit out my mouth. Fortunately I wrote a great deal down at the time (and I really should go back and re-read those letters…). Anyway.

My housemate and fellow teacher Wyatt and I shared a hastily-built apartment in an old plaster-and-concrete school building—a few rooms that used to house biological specimens in formaldehyde until a gang of students shattered the jars in the Cultural Revolution. Apparently the specimens were counterrevolutionary. Or the teacher was.

We had wall-mounted heater units, space heaters basically, and no insulation. I’d never slept with so little separating me from the outside world. In winter, the apartment was cold and damp; we wore sweaters and fingerless gloves and drank whiskey to keep warm. The heater worked, but not brilliantly—the heat focused on our desks, and it was much more effective at drying out our throats than at toasting up our rooms. Still, by having heaters at all we were living in comparative luxury set beside our students in their dorms, and for that matter many other teachers—which reinforced our desire to use the heaters as little as possible, opting for more elegant local solutions like heated blankets and thin-walled mugs of perpetually refilled tea and glass-and-felt-and-iron heating elements set on our desktops. In our second year we didn’t use the wall-mounted heaters at all.

Damn, this started to turn into the uphill both ways story. Anhui ain’t Boston—it’s warmer in winter even than Tennessee, so the absence of heat, while uncomfortable, wasn’t a huge issue. And anyway my point isn’t the chill, it’s the proximity to the outside world. When the solstice approached, it came devouring inch by inch—we watched seconds of sunlight slip away like sands running down an hourglass. Then, the sun fought back from the darkness. We felt it on our faces and in the air—and, of course, we saw it. Minute by minute, summer regained the field. And when the sun set at seven for the first time in months, we knew how the victory came to pass: we’d watched every second as the flower bloomed.

I’ve missed that since my return to the States. I don’t live as close to the outside as I did then—that’s not advisable in the Greater Boston Area, among other things, though we do keep the heater low in the winter and lack air conditioning which is a much bigger deal for the southerner in me who grew up seeing central air as basic a household need on par with a front door. I’ve been in New England five years now and every year the sun dies. It sets at four and change p.m. on the solstice, and then we start winning our way back from Hell. The battle goes well—you mark victories off in quarter-hours, oh my god the sun didn’t set until quarter ’til five today, and then, and then.

One day in early March, you wake up and find you’ve been fiat-awarded an hour.

If the year is a story, this is deus ex machina at its most blatant. Just as the Hero emerges from the Underworld, Ceres descends from on high with a longwinded speech about how farmers something something agricultural work day something else, and all of a sudden the quest is much less urgent. Oh, turns out an earthquake wiped out Sauron’s army and broke his tower. Still, might as well chuck the ring into the volcano just to be sure, amirite?

Can’t be too careful.

This is not a legislative proposal. This is not a Call to Action. At best this is a bit of nostalgia coupled with a gentle reminder: there is a living world beneath the concessions of our clocks. That’s where we all live. And while we’re forced to render unto Clock what is Clock’s, maybe we should remember there’s more to the story of our year than Daylight Savings Monday.

March 5, 2014

Time and the Sword — Also, Sword & Laser Interview!

Time works differently when there are swords involved.

I don’t mean by that the old “everything moves in slow motion” adrenaline-pumping effect associated with true oh-shit-I-will-die-in-the-next-ten-seconds panic. That kind of adrenal time-dilation goes away after your first few minutes on a fencing strip, if you ever feel it at all—a modern fencer is as safe as anyone in history ever has been when menaced with a blunt blade. The blade’s made to bend, not pierce. You, intrepid D’Artagnan, are wrapped in kevlar-reinforced armor and wear a ballistic-test mask that makes the sport almost completely unmarketable due to the fact that all players appear to be transformations of the same white-jacket-and-cheese-grater 3d model. (I guess we could maybe wear different color socks?)

No, I mean that time is more flexible. Controllable. Traversable. Amenable to influence.

We’re conditioned—especially those of us who grow up in the US-schools environment—to waiting for the next stimulus from the outside world and responding accordingly. We don’t often think about adjusting the tempo of the world around us; email comes in and must be answered. Walk sign turns to little dude and the street must be crossed. Onions are browned, garlic must be added.

Fencing, though, puts you on equal footing with “the outside world”—reduced and concentrated on the strip in the form of some dude with a sword. The outside world wants to stab you. The outside world moves in patterns—maybe it likes a 1-2 disengage for example, or advance lunges. The outside world not only knows how it wants to attack you, it knows how you’re likely to respond to its attack, and as a result it knows how to set traps. And so on and so forth. If you limit yourself to pure reaction, you end up frantic, at the mercy of the outside world’s time, and that’s a loser’s game. Give the outside world enough time, and it will skewer you. Sometimes it will skewer you on accident.

Fortunately, you have a sword, and can reclaim time for yourself.

For example: I have a tendency to retreat when I’m in a bind—say, when I’ve been caught in a parry. I’m a reasonably athletic guy; I can retreat very quickly, and most of the time get myself out of danger. But that “RUN AWAY!” move is pretty limited: among other problems, it only works at one speed (as fast as possible!), which makes it easy for a smart opponent to incorporate into his (or her) game. Once I start the move, I have very little control.

But if, instead of running away, I stay in the bind—well, then things get interesting. Held as I am in a parry, I can nevertheless choose how and when to try my next attack on a different angle. I can sense when my opponent begins her (or his) riposte, and perhaps catch her in a bind of her own. I can begin infighting (basically trying to find a way to stab the other fencer even though we’re way too close for proper stabbing) immediately, or I can create an extra beat or two of room, waiting for my opponent to make a mistake. I can build tension by drawing out an action, or I can break it by pressing rapidly for advantage. An simple change presents me with a huge range of options for shaping time.

Now, I don’t think the message here is “commit to the attack”—since part of the reason I feel like I see more options by staying in the bind is that I’m not just listening to instinct. Staying in the bind, I feel like Frank Herbert’s human being in the trap; by suppressing the animal response (“move as fast as possible to save myself!”) I’m able to see a whole range of other options and approaches to time. It’s possible that a fencer whose natural tendency was to bull-rush into engagements might see more options if she were to retreat instead; I don’t know. I’m no coach. I barely know which end of the sword goes in the other guy.

But I think this sense of time control applies beyond the martial arts. It’s easiest to see there, because the whole outside world gets reduced to the form of our opponent—but the same issues apply to ethical dilemmas, to email, to love and poetry and boardroom meetings. How do we instinctively respond to stimuli? How can we open up more options for ourselves? How can we create room to play about inside our own lives? In a way this is just another face of the karmic determination issue to which I’ve returned again and again over the last few weeks. (Fence for social justice!)

Tempo, by Venkatesh Rao, is a great book on this very subject, if you want to read the musings of someone who actually knows what he’s talking about. Or, you know, you could get yourself an epee and find a gym!

—-

A few postscripts!

1: I was on the Sword & Laser podcast last week! The show is totally cool, I had a great time, and you can see it here now:

2. A while back I posted a link to this piece of killer fan art for Choice of the Deathless, by Piarelle on DeviantArt. I may have mentioned back then that I love fan art—there’s no feeling like the sense you’ve inspired someone to create something awesome. Someone must have wanted to ensure I had a great week, because a couple days ago designer Glinda Chen sent me this amazing piece based on Two Serpents Rise. Thumbnail below, click through for full glory:

Isn’t that awesome?

Hope y’all are having a great week! See you around.

February 26, 2014

Two More Craft Sequence Books!

The big news hit Publisher’s Weekly on Friday: Tor Books has bought two more novels in the Craft Sequence! So, after Full Fathom Five, I get to play more in this world of creepy lawyers, boss skeletons, existential uncertainty and gargoyles and undead gods.

The first of the pair is done already—in fact, this morning I finished the fourth draft, a bit ahead of schedule. With luck this means I can start the next book earlier, maybe even write some short fiction in the meantime. I got a great title suggestion for a Craft Sequence short story at Boskone, and I’m eager to write something that goes with it.

Based on this deal, in the coming years you can expect from me, on the fiction front:

FULL FATHOM FIVE, due out this July, in which a priest who builds ‘idols’—fake gods primarily used for sacrifice avoidance—breaks the rules of her order to help out a friend and investigate a deal gone bad. I’m especially excited for FF5 because it pulls together characters from previous books; this is going to be a much bigger element of the Craft Sequence moving forward, tying together prior installments and crossing story-streams.

LAST FIRST SNOW, as the (working) title suggests, is set a bit earlier along the series timeline, and shows the older generation’s history. Dresediel Lex teeters on the edge of a knife, riven by protest over controversial zoning legislation, while a younger Elayne Kevarian confronts a tangle of conspiracies, revolutionaries, personal demons, and dead gods.

After that, I think we’ll revisit our friends in Alt Coulumb, and see what trouble they’ve made for themselves in our absence. (Hint: it’s probably quite a lot.)

Outside of that I have SEKRET PROJEKT #2, as well as [REDACTED], on my plate. Hopefully I’ll be able to give you less censored news about those in the near future!

In other news, I was going to write a bit here about rules, writing, and the martial arts, but as I was brainstorming I realized that you should all just go watch this clip from Enter the Dragon again:

Have a great week!

February 19, 2014

Die Hard and Fairy Tales

I think Die Hard might be a fairy tale.

Let me back up and offer context. At Boskone this weekend, which was amazing by the way, had a great time and thanks to everyone who came out and said hello, I participated in a panel about fairy tales with Theodora Goss, Miriam Weinberg, and Craig Shaw Gardener, and was thrillingly outclassed in academic knowledge and depth of study. My brain’s been firing in unaccustomed directions in the aftermath.

Tolkien says myths and legends are about superhuman figures (gods and demigods respectively), while fairy stories tell of human beings who encounter magic. A few weeks ago, I wrote about kingship, psychology, and the Wolf of Wall Street—and debate in the comments expanded to the question of how the psychological and narrative symbol of monarchy was endorsed by, and endorsed in turn, actual monarchy. To carry forward a thread from that discussion: the hero of the standard Campbell myth is privileged. His job—his hereditary job—is to repair the world. He is safe when he descends into the underworld to reclaim fire, because that’s what he’s supposed to do. It’s almost as if fire was stolen in the first place so the hero would have something to descend and reclaim! Rising from the grave, fire in hand, the hero fixes the problems of his world, and ushers in a New Order.

But the fairy tales I know don’t tend to have such explicitly “positive” endings (if we want to call the ascension of the Year King and inauguration of a New Order positive—depends on the king, I guess). You can turn Hansel and Gretel into an Underworld Journey story, but the kids bring nothing out of the forest save one another. Little Red Riding Hood straight up dies in many old versions of her tale. The bride in Mr Fox escapes with her life. One of the early Goldilocks versions ends with Goldilocks impaled on the steeple of St Paul’s, which, ow.

Contact with magic in an initiation myth may be terrifying and bloody, but it leads to power, grace, and a cool new sword. Level up! Contact with magic in fairy tales, on the other hand, does not necessarily ennoble. There are Cinderellas, sure, but just as often survivors escape with nothing but their own skin and the knowledge they almost lost it. To use a framework I’ve employed earlier—myths are badass. Fairy tales are hard core.

Or to put it another way: in our modern understanding, Campbellian myths are about knowledge, while fairy tales are about metis.

I’m stealing this word, which is Greek for ‘cunning,’ from James C Scott’s book Seeing Like a State. In the book Scott discusses how a certain kind of “high modernist” knowledge can lead to policy that optimizes for one easily-defined and desirable metric while ignoring the broader consequences of this optimization. Easy example: when thinking about your career, it’s easy to optimize for ‘highest salary’ without realizing until too late that you’ve become a nervous wreck, deeply depressed, morally bankrupt, substance addicted, etc. (Wolf of Wall Street, again. Maybe Breaking Bad too?) Scott’s examples are more societal, for example discussing how 19th century scientific forestry optimized short-term lumber yields at the price of creating forests that did not work as forests (and as a result collapsed after two harvests, taking the market with them). High modernist knowledge, then, is a specific way of knowing that assumes the ability to manipulate independent variables. Metis, by contrast, is a way of knowing that’s sensitive to specificity and on-the-ground reality. Metis is the infantry commander’s situation awareness, vs. the general’s view of units on a map.

These two ways of knowing are linked to distinctions of class and political power, in much the same way as are myths and fairy tales. To the king-mythic hero, the world can be manipulated, transformed, and saved by using or gaining knowledge / power (mystic power in stories, political power in actuality). To the fairy tale hero, or often heroine (much more often a heroine in fairy tales than in initiation myths, unless I’m forgetting something), power (mystic or political) is beyond our control. Sometimes (say, in Cinderella) those who possess power want to help us; sometimes (Hansel and Gretel, Mr. Fox) they want to hurt us. Sometimes even ostensibly benign uses of power —for example the fairy who curses the prince in Beauty and the Beast—turn out to be the source of the protagonist’s problems. The fairy tale protagonist must learn to survive in a world shaped by others’ whims. The initiation-mythic protagonist must learn to exercise unknowable power to control (or save) the world. Whatever else is going on in myths and fairy stories (and I think there’s a lot more, it’d be foolish to reduce them to just this aspect), these types of tales see power from either side of a class line.

I’m reminded here of John Connolly’s The Book of Lost Things, which is beautifully written and haunting, though I think it has a problem with women. (That’s another essay.) David (main character) wanders through a fairy tale world that has been (spoiler) perverted by the existence of a king. The regal initiation myth structure in BoLT is in fact a cruel trick played by the Bad Guy to distort the world of stories.

But if this is the case—if class dynamics are a key ingredient of fairy tales—then we have a wealth of unrecognized modern fairy stories:

80s underdog action movies. Story structure classes talk a lot about Campbell, sure, but really Die Hard is a fairy tale. Little John goes into the woods of LA looking for his lost wife, encounters a wicked nobleman who wants to do (bad stuff) and has to defeat him by being clever, strong, and sneaky. The whole movie opposes high modernist knowledge—Gruber’s “plan” and the building’s super-security—to metis, here in the form of John McClane’s beat cop street smarts. The first Lethal Weapon also fits the bill—Murtaugh and Riggs wander into the woods, also of LA, and end up fighting rich and powerful noblemen in order to survive. Their opponents? A paramilitary conspiracy, complete with grand schemes, political authority, and all sorts of high-tech equipment. Basically any of the “fight the big boss” stories, including Enter the Dragon, can be thought of in this way. Oh! And let’s not forget Alien and Terminator, both of which oppose a working class woman—a trucker in the first case, a waitress in the second—to sexual creepy-crawlies and the technocratic military-industrial complex. (Which sometimes doubles as a sexual creepy-crawly; Ash trying to choke Ripley with a rolled-up girly mag is one of the most skin-crawling scenes in Alien, at least to this viewer.)

(Sidebar: This notion of power disparity also may explain why Steven Moffat’s vision of Doctor Who as a fairy tale has never quite convinced me, since New Who mythology sets the Doctor up as a being of unknowable power himself, which makes it hard to evoke that fairy tale aesthetic.)

Our mainstream, tentpole movies have turned to myth rather than fairy tale recently—Captain Kirk becomes a Destined Hero rather than a guy trying to do his best against impossible odds. That’s not a priori a bad thing, stories and life both change after all, but when everyone’s a damn Destined Hero the pendulum might have swung too far. I wonder how we could recapture this older dynamic. Maybe I should slink off and write an 80s action movie for a while.

—

Some unrelated current-eventsy notes:

1. SFWA stuff: I agree with Nora Jemisin, John Chu, et. al. about this petition fiasco. The SFF community, and SFWA in specific, should be a place of support, friendship, cooperation, understanding, and action. We should be stretching our imaginations, and applauding and supporting others who stretch theirs. To the extent those two sentences don’t describe the community or SFWA, we have more work to do. Doing this work, and talking about how to do it, may hurt. Most work does. But that’s not the same as oppressing and censoring people. So, count me in with the insect army.

2. If you have any interest in Star Trek whatsoever for the love of god run don’t walk and download John M Ford’s The Final Reflection. It’s bloody brilliant. A Boskone panel convinced me I should read Ford’s work; the Star Trek novels are most widely available due to some rights and will-related madness which if I wrote about it here I’d just write a scream for the next few thousand lines. I’m reading How Much for Just the Planet soon. Whenever I find a new author I like this much, I feel like I’ve discovered a whole new universe, and not in the Species 8472 way.

February 12, 2014

Booker DeWitt at Wounded Knee: Baptism in Bioshock Infinite

I just finished playing Bioshock: Infinite. It’s a great game. The play is smooth and fun, with swashbuckling sky-rollercoaster antics and magic crows flying out of your hands. And the soundtrack, my stars and garters, the soundtrack. (If you want to get me on your side there is no better way than having a barbershop quartet cover “God Only Knows” in the first 20 minutes of a game that’s supposedly set in 19-fucking-12, combining worldbuilding awesomeness and male close harmony and “wait a second is that really-” for a shot of pure brain joy.) The two central characters of Booker DeWitt (your not-so-silent protagonist) and Elizabeth, the girl he’s trying to rescue from flying racist sky-city Columbia, are engaging and fabulous. I’ve never felt so damn *concerned* for a tagalong NPC in a game. I cared about Elizabeth. I wanted to help her, protect her, make her happy, and, hell, just to wander around the city with her hanging out. Not because the game told me I was supposed to like her—because the story was built so that I just *did*. Serious Final Fantasy VI level stuff here. If there’s a better compliment to game, I don’t know how to offer it.

And on top of and beneath all the Erroll Flynning and the magical crows and the time travel, Bioshock: Infinite is a brilliant investigation of the sacrament of baptism.

(WARNING: In case you didn’t guess, I am about to mercilessly spoil B:I. Gamers, if you haven’t finished it yet, what are you doing here? Theology folks, I’ll try to bring you up to speed on the story’s conceits as quickly as possible.)

(WARNING 2: I’m talking theology here, so a bit of background: most of my theology is early C20 German existentialist though there’s a lot of Augustine up in the attic too, for which thank you Dr. Richardson. As with all theological argument, this is me groping at the edge of immense symbols with imprecise words & trying to describe how I’ve lived with, around, and occasionally through them. Mileage varies.)

Consider a soldier named Booker DeWitt, who participated in the massacre at Wounded Knee, the U.S. Army’s wholesale slaughter of Sioux men, women, and children. Broken by his own actions, DeWitt seeks solace in religion. He goes down to the river to pray. A preacher offers him baptism.

This is where things get weird. In one timeline, DeWitt accepts baptism, and rises from the pool feeling his sins not merely washed clean, but *justified*—he is God’s agent in the world, and he strides forth to remake Earth in the service of his white American deity. He takes a new name to represent his new life: Zachary Hale Comstock. And since delusions of grandeur are inferior to, you know, actual grandeur, he enlists the aid of a brilliant scientist who can control quantum stuff and create tears between realities. Said scientist builds for Comstock a flying city from which he can dispense justice on the world below: Columbia! So Comstock has his empire, but he still needs an heir. Unfortunately, quantum tomfoolery has left him infertile—so, easy enough, since we can open tears from one reality to the next we can just reach into a neighboring reality and pull a child out of them—a girl who shares his own DNA even. Comstock does this, names the girl Elizabeth, and locks her in a tower, raising her to maturity and attempting to brainwash her to share his ideals and vision for the world. The brainwashing is not very successful.

“Meanwhile” (hah!), in another timeline, DeWitt refuses baptism, goes to New York, gets married. His wife dies, leaving behind DeWitt and their baby girl, Anna. Single dad DeWitt tries to keep his shit together, fails, and falls into a depressive spiral of drink and gambling. Debts mount. He’s in trouble. One day a mysterious scientist arrives and offers him a devil’s deal: DeWitt’s debts will be forgiven so long as he gives up his daughter. DeWitt, at rock bottom, agrees. He comes to his senses, chases after the scientist, but can’t stop the “theft” of his child. With her gone, he sinks further into depression and drink. Somewhere in all this he joins the Pinkertons and spends 20 years beating labor organizers over the head with a lead pipe.

Until one day the same scientist, for reasons of “his” own (it’s complicated), returns, and offers DeWitt a second chance: to visit the alternate reality super-racist sky city of Columbia and steal “the girl” (Anna, now Elizabeth) back from him. When our heroes piece all this together, in the story’s final act, they understand what they must do: go back to the moment of Comstock’s baptism and drown him—that is, Booker must inhabit Comstock and drown himself, with Elizabeth’s help.

On its surface this story seems to come down pretty hard on baptism. DeWitt-turned-Comstock is reprehensible—a villain so villainous he borders on parody, as Yahtzee’s review observes. (Though Comstock’s sins are also the arch-sins of the United States in ways that make Comstock’s madness intelligible at least to this US-American; Comstock’s our heart of darkness, the evil we fear might be, and sometimes know is, the truth beneath our pretense of opportunity and grace. Comstock is us—literally, in this game! But this relies on a lot of cultural context to which non-US-Americans might not have access; I dunno.) Baptism is his origin story; the first sin of Zachary Hale Comstock, it seems, is his belief that a little fresh water could wash away the blood of Wounded Knee. But I think the story’s subtler than that.

See, baptism is a discontinuity—a tear. At the very least, setting aside all questions of metaphysics, it offers us a narrative break from the past. That distance gives us the strength to appreciate the depths of our mistakes, and the spiritual leverage to mend them and live better. Baptism is not God saying “Hey, you’ve done really well so far, have a nice bath!” We need baptism, say faiths that rely on the sacrament, because we haven’t. Because doing well is impossible. Because we live in a suffering world, because we benefit from that suffering, because we pass it on to others, because almost all of us who can read this blog post (if we’re frank about it) live with our feet on the necks of people we can’t name, running back centuries. And that’s for those of us who did not actively bayonet children during one of the darkest and bloodiest moments of American history! To do meaningful work in the world, to be honest with ourselves, we must wake up. We must embrace a moment of change, a spiritual inflection point. We must acknowledge our role in oppression and work to stop oppressing. (Notice parallels to the stuff I wrote about karma a few weeks back? The concepts of sin and karmic determination approach similar truths from different angles, I think.)

Seen this way, both Booker and Comstock refuse baptism after Wounded Knee. Booker recognizes his refusal, and sinks into despair, alcoholism, and gambling until he’s so low he sells his daughter to save his own skin. Comstock twists the offer of rebirth—he uses the discontinuity of baptism to *justify* his past actions. Obviously God approves of my deeds, or else He would not forgive me. Right?

Hah.

Comstock was no more prepared to confront what he’d done than was DeWitt. He mythologized it, rather, created an elaborate fantasy world in which his every evil was a virtue. (A parallel to certain other ubernationalist video game franchises, maybe…) To defeat him and save Elizabeth, DeWitt must force Comstock to accept the most profound narrative discontinuity, and to accept it himself—to embrace baptism and die.

DeWitt / Comstock drowns. Elizabeth vanishes, because without Comstock she does not exist. Credits roll.

And then…

After the credits, we join DeWitt in his office. In the next room, a lullaby plays. He stands, walks to the door—hesitates with his hand upon it— “Anna?”

He pushes the door open, and finds his daughter.

Since Comstock never came to be in any alternate timeline, no one stole Elizabeth from DeWitt. She remains Anna, and the future is unwritten.

Beautiful.

(Yes, okay, we never actually see the baby in the post-credits scene. There’s room for ambiguity, though I think the reason for that is to leave open the question of whether it’s Anna or Elizabeth in the crib.)

But, and here’s the key: for this ending to work, we *must believe* that the Booker DeWitt we join post-credits is a different man from the Booker DeWitt who sold his daughter, or anyway that he will become a different man. Granted we see little evidence of this, but if we’re to feel at all positive about the ending we need to believe that Booker will be as good a father to Anna as he became to Elizabeth by the end of Bioshock Infinite—which means that he’ll get his act together, stop drinking, stop gambling, pay off his debts and raise his child. Booker will emerge from his self-destructive spiral and become a man good for something other than breaking the world. (And if Booker can, maybe America can too.)

Booker DeWitt accepted the sacrament of baptism and was reborn.

And the story’s pro-baptism logic goes even further! Elizabeth is an admirable woman: strongwilled, joyful, idealistic, practical. She has suffered horrible things during her captivity, most of which are left vague, but still—she asks Booker to kill her rather than let Comstock take her back, which suggests some pretty creepy shit. This woman is worthwhile, and DeWitt’s baptism, while severe for him, goes even further for her: if we believe she’s in the room in the final scene, she’s been reset to literal infancy.

DeWitt, mind, doesn’t make this choice *for* Elizabeth. She holds all the cards in the final act: she can see every alternate reality, and shift between them at will. (It’s possible that all the tears are actually game-representations of the operation of consciousness—that we’re inside Elizabeth’s head the entire time, or even inside of Booker’s, all of BI being a single moment of transcendent experience during his baptism after Wounded Knee—but this isn’t that essay.) The way the story’s presented, Elizabeth decides that literal rebirth is preferable to her past. She’s willing to abandon everything she *is* in order to escape what’s happened to her, and what she’s done.

If there’s a more extreme form of baptism, I haven’t seen it yet.

Now, there’s another way to spin this final moment: Elizabeth and DeWitt want to save New York / the world / herself in *all* timelines, so Comstock must die in all timelines, which means Elizabeth must sacrifice herself. She, as Elizabeth, will disappear—but she, as Anna, will have a chance to grow up with her real father. By submitting to baptism and rebirth, she keeps herself from ever becoming the tool of Comstock’s vengeance on the world. One baptism for the forgiveness of sins in all realities—or the prevention of future sins. (This is starting to sound very Tielhardian, I guess.) I think the story accepts both spins, maybe even at the same time. People are complicated, especially time-traveling realty-hopping omniscient people.

Either way, Bioshock: Infinite might seem to take a hard stance against baptism, but it’s actually one of the most thoughtful investigations (and IMO endorsements) of the concept I’ve seen. I understand the game came under some fire on release for being “antireligious.” If cutting open tough theological concepts and developing them through the media of play and storytelling is “antireligious,” maybe modern faith needs more antireligion in games, not less.

February 5, 2014

What a Twist—Real Life, Directed by M Night Shyamalan.

We live in a twist ending world.

I feel like the mid-90s through early oughts were the Golden Age of the Twist, but even though they’ve receded a bit from their M Night Shyamanence in the last decade or so they’re still a huge part of the modern writer’s toolbox. Some of the great all-time cinema moments are twists (and if you don’t see the spoilers coming hot and heavy in the next few minutes I suggest you leave now and go somewhere pleasant, preferably with a beach, good surf, and no wi-fi). Think about it:

I AM YOUR FATHER

TYLER DURDEN IS HOBBES

BRUCE WILLIS WAS ROSEBUD THE WHOLE TIME

CHRISTIAN BALE IS ACTUALLY CHRISTIAN BALE

KEYSER SOZE WAS IN THE HOUSE ALL ALONG

PAUL BETTANY IS MADE OUT OF CHOCOLATE

TOM HARDY IS MARILON COTILLARD, OR WHATEVER HAPPENED AT THE END OF THE DARK KNIGHT RISES

These moments are needles stuck into our heads. I love their power. I’m a bit of a twist junkie when it comes to storytelling. And yet…

Twists do rob us of drama. The end of Usual Suspects feels brilliant the first time you watch it, and on the mandatory rewatch where you snag the clues that were “there all along”—but on repeat viewings you (or I) come to feel that on some level Keaton’s relationship problems, McManus’s general psychosis, and Benicio Del Toro’s tragic quest to make himself understood in an uncaring universe don’t matter. The gang starts off manipulated but unaware. At the half-mark they learn something about the extent to which Soze’s playing them, but they can’t do anything about it. When they finally discover the truth, they die and the movie ends. In a way the whole thing is a single dramatic beat: Soze tries to trick the audience as well as Keaton’s crew and the FBI, and succeeds. One magic trick. It’s a brilliant trick! I love The Usual Suspects, and whenever I learn a friend hasn’t seen it, I’ll scurry off to schedule a viewing party—because while the trick itself loses its spark when you know how it’s done, there’s a pleasure in watching someone else fall for it the first time.

But it’s a very different experience from watching a film that uses pure dramatic storytelling, like Thank You for Smoking or The Fellowship of the Ring. (Confession: the only other thing these movies have in common far as I can tell is that I’ve seen both of them an embarrassing double-digits number of times and thus can talk about them from memory. Maybe I’ll add Newsies into the mix later for good measure.) Characters in these stories have desires, try to achieve those desires, and succeed or fail because of opposition or internal weaknesses, and it all matters. These stories may surprise us, but the surprises don’t tend to eclipse the rest of the story. Journalist Heather Holloway (played by Katie Holmes, and after TYFS and Mad Men can we maybe retire Holloway as an ironically significant surname at least for a few years?) turns out to be sleeping with Nick Naylor (okay, maybe I should just let these names go) in order to write her hard-hitting expose on the man and his industry; this is a surprise but it doesn’t abrogate their relationship so much as cast it in a different (exploitative, vicious, sexy) light. Ditto with Boromir’s betrayal at the end of Fellowship.

I’ve read hard-hitting indictments of the drama-sapping twist (and of all storytellers so lazy as to employ it). But… Okay, so twists can rob stories of the potential for drama. If so, why do we use them? In a marketplace with a billion stories competing for our attention constantly, why would a storyteller ever use a device that forces them to make their stories less dramatic?

Maybe the answer’s purely market-driven: viewers are more likely to inflict stories with twists on their friends, so they can talk about the twist. I don’t like that answer, though; I don’t know anyone who thinks about storytelling in this mercenary a fashion, but hell, maybe those people do exist! Maybe there’s some creepy evo-psych hardwiring that makes sharp twists hit us harder. But that way lies tautology & madness (“we like it because we do”) so let me recoil.

The answer I like is the one at the very start of this article (What a twist!): “We live in a twist-ending world.” The world, our friends, our families, our societies, our histories, our preferences, and even our own minds really aren’t what we think. They’re bigger, weirder, and deeper. We’ve become so used to the revelation that Strange Things are Afoot at the Circle K that we’ve come to expect it from our stories, too. Our history is wrong—the cowboys aren’t the good guys, the Indians aren’t savage, the High Middle Ages were cool but really didn’t contribute much to burgeoning Afro-Eurasian civilization (outside of some awesome polyphonic chant), Jefferson was… not a saint. The Aztecs sacrificed human beings, sure, but some scholars feel that contemporary European states (I mean contempary with the Aztec empire here) executed more of their own people overall. We think Coke tastes better than Pepsi unless we don’t know which one we’re drinking. We think we’re angry when we’re sad. We think we’re hungry when we’re thirsty. We think we’re oppressed when we’re the oppressors. Our friend who seemed happy when we last spoke threw himself off a bridge. We drink because we want to, only we don’t. So when someone shows us, on screen or in a book, a window into a world where characters take dramatic action on false premises only to discover their errors too late, we say “oh, yeah, I know exactly how that feels.”

If that’s the reason, though, then it informs the kind of twist we as writers should be preparing. A good twist doesn’t just yank the audience’s chain. A good twist should reveal the world in which our characters live to be bigger, deeper, and more complicated than we initially supposed, confronting characters and viewers at once with the limits of their perception. The twist isn’t so much that Vader is Luke’s father as that, holy shit, this oppressive Imperial evil is intimately connected with Luke, the Jedi, and by extension everything we thought was good. The enormous dragon of Charles Foster Kane was, at some point, an innocent happy boy on a sled—which breaks open both the myth of invulnerable irredeemable Charles Foster Kane, and the myth of the sacred innocence of happy little boys on sleds at once. Jack contains and conceals Tyler (or vice versa) in exactly the same way that the fluorescent middle-management cube farm contains and conceals the will-to-power of late millennial manhood. (And womanhood, and personhood in general, but Fight Club is more concerned with manhood and IIRC white manhood in specific.)

(Fight Club’s a weird movie, by the way, and I don’t mean by the discussion above to suggest that I agree with everything it says. That’s for a longer article which I may never get around to writing. But I think it uses the twist well by opening new depths for its world.)

That kind of twist, when it works, not only mirrors the weird and unsolved nature of our existence, it confronts protagonists with the kind of challenge we all face with disturbing regularity: some number of things I thought I knew are wrong. What should I do in this situation? What’s moral? What’s practical? What’s sane? How can we move forward?

It turns out that the galaxy-spanning empire you’ve been fighting is actually your own galaxy-spanning empire. Your father built it for you. What now?

And—this being why I love Star Wars—the story refuses to let the protagonist get off so easy as “frustrate his plans and end it all by jumping off a building.” Nope. Luke survives to ask himself what he’s going to do next.

So may we all.

—

(By the way, if the topic of this post interests you at all, run, do not walk, to your nearest store and buy a copy of Sara Gran’s Clare DeWitt and the City of the Dead, a trippy and philosophical mystery novel that is all about this sort of thing.)

January 29, 2014

Giant Super Mega Post of News and ARCs and Schedules and Board Games

I’m giving the OMNISCREED 4000 a break for the week, since there’s some cool stuff to report from Casa Gladstone. First, roll tape!

Last Friday I sent in the final page proofs for FULL FATHOM FIVE, the next book in the Craft Sequence. And the same day, I received a few of these beauties. The cover looks great—I’m amazed by Chris McGrath’s ability to come up with powerful work that somehow fits with the series.

I’ve received enough questions about the cast list that I think I might need to spoil it in advance. So far, all I’ll say is that FF5 does feature the return of some old familiar faces from Two Serpents Rise and Three Parts Dead, facing brand new problems. You’ll like it a lot more than they will, I promise.

Launch day’s July 2014. Watch this space for more news and possible giveaways.

WORLDCON MEMBERSHIP DEADLINE

If you haven’t yet become a member of WorldCon (this year, it’s LonCon 3), then you should do so before Jan 31 if you want to be able to nominate people for the Hugos and the John W Campbell Best New Writer Award. Curious as to how? I’ve presented my argument, and easy-to-follow directions, here.

As for folks who are eligible this year for the Campbell Award this year—I’m in my second (and final) year of eligibility. I’ve been nose-to-grindstone this last year when it came to reading new stuff, and sadly most of the new stuff I’ve read won’t come out until 2014! That said, you should check out Wesley Chu and John Chu— Wes writes action-packed alien madness, and John writes heartfelt worldbuilding-heavy SF.

I’M ON THE FUNCTIONAL NERDS PODCAST THIS WEEK

If you have a brief commute and like hearing folks talk, why not hear me, John Anealio, and Patrick Hester talk about books, tiaras, and neat stuff? Here’s the link.

CHOICE OF THE DEATHLESS IS ON iOS HOT LIST

Someone over at Apple thinks Choice of the Deathless is cool. If you haven’t played it yet, give it a shot. It will scratch the Craft Sequence itch and tide you over to summer.

BOSKONE SCHEDULE

I’m at Boskone next month! Check out all these things I’m doing. I’m looking forward to everything, but the “Writing Fan Fiction for Kids” event should be a hoot. Plus, Mur!

Writing Fan Fiction for Kids with Mur Lafferty and Max Gladstone

Saturday Feb. 15 10:00 – 10:50

Campbell Award winning authors Mur Lafferty and Campbell nominee Max Gladstone introduce kids to writing fan fiction for children.

Mur Lafferty, Max Gladstone

Urban Fantasy in Transition

Saturday Feb. 15 12:00 – 12:50

Urban fantasy has a long history within fantasy literature, but it’s certainly gained new prominence recently. How has the definition changed over time? What influences have helped to shape urban fantasy? How far back into the literary past does urban fantasy reach? How might it evolve in the future?

Leigh Perry (M), Christopher Golden, Melinda Snodgrass, Mur Lafferty, Max Gladstone

Gender Roles in _Doctor Who_

Saturday Feb 15, 13:00 – 13:50

The characters (Companions, foes, etc.) in TV’s _Dr. Who_ have included men, women, and “other.” How have they all conformed to “expected” gender conventions? Discuss notable breaks in tradition, giving examples (this will not be graded.) Note: you may also include Captain Jack and the Doctor’s Wife.

Laurie Mann (M), LJ Cohen, Carrie Cuinn, Julia Rios, Max Gladstone

The Enduring Power of Fairytales

Saturday Feb. 15, 17:00 – 17:50

What is it about fairytales that holds the imagination — and can it survive a few tweaks? Fantasy is rife with retellings of myths and legends, but why are today’s authors and screenwriters so radically changing classic fairytale characters (as in _Wicked_) and/or even outcomes (as in _Once Upon a Time_)?

Theodora Goss (M), Mary Kay Kare , Craig Shaw Gardner , Max Gladstone

Who’s in the Attic, What’s in the Basement, and I Don’t Know Is Under the Bed

Sunday Feb. 16 13:00 – 13:50

A panel discussion of the things that give us goose bumps, send chills down our spines, or otherwise scare the daylights out of us.

Gillian Daniels (M) , Darrell Schweitzer, F. Brett Cox, Paul G. Tremblay, Max Gladstone

Reading by Max Gladstone

Sunday Feb. 16 14:00 – 14:25

Guys I will read so much stuff you have no idea. Can I read an entire book in twenty-five minutes? I don’t know, but maybe you are interested in finding out! I sure am.

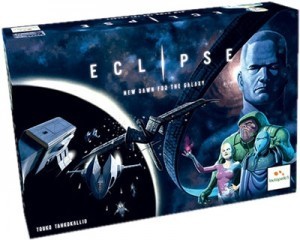

YOU REALLY SHOULD PLAY ECLIPSE: A NEW DAWN FOR THE GALAXY

Want to conquer the universe? Uncover strange alien technologies? Dispatch Dreadnaught fleets to crush your friends and intimidate your enemies? Become an ancient race of inscrutable monolith-builders who hover implacable and distant above the carnage? Or just play a race of crazy plant-people? Want to do all this in the form of a beautiful, elegant board game that does not require twelve hours to play?

Enter Eclipse: A New Dawn for the Galaxy. Eclipse is a Finnish game, further support for my theory that Good Games Come From Places With Nasty Winters. (A corollary to my theory that Good Ice Cream Comes From Hot Countries.) You and your friends play human and / or alien factions spreading their hands / tentacles / pseudopoda across Known and Unknown Space. Each of you starts with a teeny civilization, confined to one corner of the galaxy. You win by accumulating the most Victory Points (natch)—a semi-secret currency that can be gained by developing territory, engaging in diplomacy, winning battles, building monoliths, and developing high-level science.

Admittedly this sounds exactly like the kind of game we made computers to play: tons of bookkeeping, addition, micromanagement, and related nutjobbery. But the designers took the existence of computer games as a challenge, I think: “How can we” (they seem to have said) “make a board game this big without making the players once think, I wish I had a computer to do the math for me.”

The answer is elegance. For example: each player has an “upkeep track” consisting of circles covered by little wooden “influence discs”. To take an action on your turn, you move an influence disc from the upkeep track onto the action you want to take. This reveals a number, which is the amount of money it costs to keep your civilization out of bankruptcy this turn. Generating more money? You can take more actions. But watch out—you spend the same influence discs to control star systems. As a result, your sprawling star empire costs a lot more to control than a small, focused colony cluster. Depending on their income, civilizations can be paralyzed by their own bulk. Some technologies give you more influence discs; in the event of bankruptcy you may have to remove discs from your colonies, effectively giving up control of an entire star system—which might be great, or horrible, depending on your goals. I can’t remember the last time I saw such a simple mechanic with such complex implications. It was probably in Advanced Civilization. And that’s just one aspect of the game. Combat, colonization, and technology research are every bit as elegant, and all mechanics interlock.

Speaking of combat, I love how this game represents interstellar warfare. Spaceships are big, expensive, and slow. As a result, combat between players is rare—but each exchange is fraught with import. A battle swinging your way or your enemy’s may not outright lose you the game, but it may radically alter the direction of play. Going to war puts your civilization at hazard. You may win big. You may collapse. In my group’s first game, my friend Dan built a Maginot line of starbases at the last possible minute to stop Vlad’s hyper-cruisers in a Second Battle of DS9-style omnifracas which devastated Vlad’s fleet and indirectly won Dan the game—though it could have gone either way. So. Much. Fun.

There’s a lot more to love: the aliens all have subtly different mechanics than the humans, which skews their play in cool new ways. Since each action requires an Influence Disc, even bookkeeping stuff like upgrading your starship becomes frought with dramatic import—since by choosing to do it, you’re choosing not to do something else which might be really important. There’s chance enough to skew the game in fun new directions, but not so much chance that skill becomes irrelevant. And all this gets done in about 30-45 min. per player.

Also, and I cannot stress this enough: you can win by seeding your territory with inscrutable 2001-style Monoliths. What are you waiting for.

(Also the publisher has killer customer support. The game I received was missing a few minor pieces, and they sent replacements even though they are in Finland. That seems above & beyond to me.)

January 22, 2014

Sacred Kingship in Fantasy (and the Wolf of Wall Street)

As a fantasy writer, I have a chip on my shoulder about monarchies.

There are good reasons for this! It’s pretty weird for fantasy lit to embrace a form of government that, when it survives at all in the modern day, tends to fall somewhere between a charming affectation and a confusing throwback. So many books about rightful kings and the return of a grand sovereign who will Fix Everything. So many destined heroes and heroines. Blood royal by the gallon. And to make matters worse, some fantasy novels consume hundreds of pages taking nuanced and risky political positions like “serfdom is bad” or “maybe some people who are not aristocrats would be good at governing,” which seems to me the political equivalent of singing the Welsh longbow’s praises to the 1st Infantry Division.

Now, the genre’s been veering away from this rock. The Lies of Locke Lamorra and The Name of the Wind, both wildly successful in the field, have hardly any kings at all. China Mieville’s fantasies engage with 19th-century through postmodern modes of oppression and government. The Shattered Pillars is in some ways a restoration-of-the-King fantasy, but one of the central noble characters has explicitly rejected any path to the throne or to aristocratic power generally, and the other spends a lot more of the first book wanting to save his commoner girlfriend than he does thinking about Ascending to the Throne. Karen Lord’s Redemption in Indigo isn’t concerned with medieval kingship. Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death isn’t either, though it’s a postapocalyptic fantasy and doesn’t belong in the same category as the others I’ve listed here. I have my necromancer-lawyers in a fantasy analogue of late-millennial capitalism. But still, the issue of kings arises.

I’ve wrestled with this question on and off for years, and this year I ended up on a panel called Why Root for Monarchies?, moderated by Vanessa Layne. I went in raring for revolution—and then Ms. Layne mentioned that she approached the topic from her background in Jungian analysis.

At which point a lightbulb clicked on in my brain.

Because stories are dreams, in a way. And we are everyone in our dreams—father, mother, kitten, needle-toothed-monstrosity. (At least, this is an interpretive framework I’ve found useful.) When we’re writing about kings, we’re writing about ourselves as kings of ourselves.

Because we are all kings, aren’t we? Or queens. Reigning monarchs, whatever our gender.

By which I mean: we stand in the center of our own minds—of our awareness that fills the universe we know (by definition). The decisions we make every day shape that universe. When the monarch of our mind is diseased, warped, evil, then the land—the mental land, the soulscape—twists and decays. When the monarch of our mind is just, upright, generous, and kind, the land calms, and flourishes. Possibilities grow. New life enters the world. Nothing can live in the land of the evil king because the evil king allows nothing to live there—nothing surprising, nothing beautiful, nothing that can flourish or transform or challenge. The good king welcomes, and so allows growth, transformation, and the full richness of the world.

So a certain kind of spiritual kingship story can be profoundly democratic. Most of our talk about the Campbellian monomyth and mystic kingship misses this critical point: if the monomyth is an initiation ritual, it’s a ritual which all members of society must undergo. It’s not something special, a secret marker for kings or tribal leaders; all adults of the tribe walk this path. To reach adulthood is to be Luke Skywalker, or Arthur, or Aerin-sol.

And when I say all members of society I do mean all. Monomyth discussion can get weird and gender-essentialist for historically contingent reasons—but I don’t see anything gendered about the need to achieve generative agency in our own minds and lives.

This same kind of logic shows up in Vajrayana Buddhism, too—tantric meditation refigures the adept as an enlightened divine being in the center of a mandala-palace. Every single adept. Initiations are large ceremonies: thousands of people are all being told at once, “Envision yourself as a divine being at the center of the universe.”

So, am I giving monarch-apologist fiction a free pass? No. The spiritual self-rule I’m talking about (which by the way also plays nice with Christian theology; if you think what I’m describing sounds awfully prideful I humbly submit to you Augustine’s discussion about standing upright in The City of God, not to mention Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor scene from Bros. K) is the absolute reality; secular kingship is the shadow that reality casts on the cave wall. To play in this territory, stories need to guide the reader away from the shadow, to the reality. To make Arthur a secular Christ, storytellers gave him a mystic birth, a wizard advisor, draconic signifiers, a magical sword, tragedy and destiny and the Holy Grail and Green Men and all the like precisely because these things were weird. These are symbols that Arthur exists in the realm of the sublime, of the archetype—White’s “Island of Gramarye” where you and I shall fare.

The funny thing is, because of their success, these same symbols have become so common as to be seen to define a world in which they make sense. Rather than pointing us away from the cave wall, they posit another cave wall with a slightly different topology and physics. When the reaction to the phrase “this is a magic sword” is not a feeling of wonder and awe—of being invited into the sublime by an object’s presence— but instead the question “is it more, or less, magic than that guy’s magic sword?” then I think it’s safe to say we’re back from the clouds and rooted once more in the mundane world, no matter how many wizards are whizzing about.

I don’t mean that rules-based high fantasy cannot evoke the sublime; it just has to evoke the sublime in such a way as to signify that something outlandish is taking place even by the standards of an outlandish world. The Lord of the Rings does this well. So does Guy Gavriel Kay’s Fionavar Tapestry. So do Ursula K LeGuin’s Earthsea books—Earthsea’s magic is systematized, but by pressing around its edges LeGuin turns us again and again to the sublime.

And, of course, it’s possible to deal with these questions without any literal monarchs whatsoever! Which brings me to The Wolf of Wall Street.

Wolf presents two opposed versions of adult manhood: Jordan Belfort, introduced riding a white Porche getting a blow job from his supermodel wife, and Patrick Denham, the FBI agent investigating Belfort for fraud. Belfort’s character is presented as a secular monarch of US culture. He has the castle, the millions, the everything. Denham wears a decent suit, and rides the subway to work. His scenes are tinged a slight gray, with washed-out colors.

Wolf of Wall Street, I think, is a brilliant depiction of the Wasteland of the Evil King. In Belfort’s world, no one is old. In Belfort’s world, no one is wise. In Belfort’s world, there are no black people except for his female housekeeper. In Belfort’s world, women exist entirely for sex and money laundering—and (this is my favorite bit) he’s not even any good at the sex! Sexuality defines his physical life and the few times we see him get busy, he’s horrible at it. Like, fourteen-year-old-boy-in-back-of-Dad’s-Camero, “um-shit-where-does-this-bit-go” horrible. And at the apex of Belfort’s anti-initiation, the moment of grail-finding in a spiritual kingship narrative? He finds his Grail, the ur-Quaalude, consumes it and transforms into an infant, unable to speak or walk or even crawl, in one of the best sequences of physical comedy I’ve ever seen in a movie. For all the lushness of his surroundings, he inhabits a blasted land. (Come to think, he’s just as bad at drugs as he is at sex!)

The few scenes which we don’t see through Belfort’s eyes we see (with one brief exception) through Denham’s—and these are the only scenes where the movie shows us women who aren’t airbrushed supermodels. Near the end, we join Denham on the subway; a silent, unsensational minute or two of film in which he reads the paper, sets it down, and sits alongside the usual inhabitants of a New York subway car, old and young, of a range of body types and skin colors and styles of dress and affect. No one talks, but they are there, being themselves. No one needs to serve anyone. The scene transcends in just how uncanny it feels, how different: how much it shows Belfort’s fantasyland for the husk it is. Denham is the sacred king. Belfort is doomed to himself. And the film’s last shot indicts us for how hungry we are for secular kingship, and how little we understand the sacred variety.

In sum: the Monarchies panel reminded me of a symbolic role kingship plays in stories that I’d forgotten. The role is complicated, though, and it’s not about kingship so much as initiation, ascendancy, and adulthood—about becoming. Shiny hats might help get the point across, but shiny hat and throne are only trappings of a deeper reality. The reality deserves our striving. The trappings don’t deserve much at all, really.

—-

(All that said—I had an awesome time at Arisia. Great panels, great questions, great thought. Still recovering, but that’s to be expected. Thanks to the whole con team, and especially to Shira Lipkin, who organized the Literary track!)