Remittance Girl's Blog, page 17

December 15, 2013

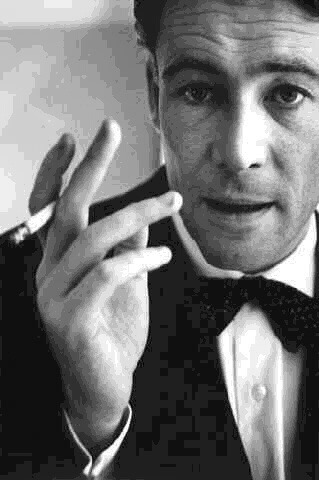

HandSome Devil

Peter O’Toole died today. I remember my mother telling me she had met him at a cocktail party in London in the 60′s and turned into a pillar of salt looking into his blue, blue eyes. She said he was ‘hyperbolically handsome.’ We were watching Lawrence of Arabia on TV; I was only twelve at the time. I asked her what that meant. “Some men are good looking,” she replied, ” and some men are so beautiful they fuck you up for life.”

I was left to look up the word ‘hyperbolic’ in a dictionary for myself. My mother always was a little self-absorbed and careless with language around her children.

For me, it’s not his eyes, or the face, or the pecs, or the ass… It’s the hands. Not any particular kind of hand, either. I realize Mr. O’Toole has rather long, graceful, feminine fingers. And, yes, they make me quiver. But I’m not a hand snob - it’s the belongingness of the hands to the man that counts. The hands need to speak to the man.

I’m just as attracted to rough, grubby, calloused, childlike, scarred-up hands. Short-fingered, hair-dusted, gnarled-knuckled, nimble-quick, tapered, blunt-ended, expressive or still. A man can alter a lot of things about himself; he can change what he wears, build muscle, get wiry running marathons… but the most he can do to change his hands is to get a manicure.

When a man’s words correspond to his hands, an evil little click goes off in my head and I’m gone. I don’t mean that if he has scarred up, calloused hands he should talk like someone who works with his hands. It’s more subtle than that. It’s a liminal agreement of form and content. Hand-to-mouth coordination.

Certain men’s hands become a great distraction. I’ll sit wordless and mesmerized. Yes, of course, it’s the full-sensory fantasy of those hands at work. Caught up in my hair, curled around my neck, full of my thigh, on me, in me, smelling of me. But, it’s also the less personal narrative of that hand slipping into a pocket, holding a pen, lifting a cup, using a knife, clutching a steering wheel. And, of course, possessively curled around the owner’s cock.

So, ‘handsome’ is not about beauty. Lithesome, winsome, loathsome, lonesome, cumbersome… The suffix ‘some’ denotes a thing or person in possession of that quality. You might think that the etymology stems from someone whose hand you might accept in marriage, but the ‘hand’ in question is a measurement of size, inferring largess, generosity and aptness to purpose.

When I look at a man’s hand, I think about the purposes to which they’ve been turned and to which they could be turned. History in a caress or a blow. It is the narrative that cannot lie.

December 13, 2013

Surveillance and Selfies

We have a wired world that exhorts us to reveal ourselves. Of course, this didn’t start with the web. It was brewing since we said goodbye to our Victorian reserve. Early celebrity magazines like “Tattler” and “Hello” both served and punished those who featured in them; congratulating the rich and famous on their weddings, and publicly pillorying them for their excesses and social faux pas. But the exposé talk shows of the 80′s, with their cast of families falling apart, people coming out on live television, the spectacle of humanity in its ugliest moments, etc. brought this push for full public disclosure to a fevered pitch. The formula being that if celebrities are people whose lives are fully exposed, then we can all be celebrities if we fully expose ourselves. And this is formalized in the structure of reality TV and taken to its limits in the spectacle of self-made amateur porn.

We have a wired world that exhorts us to reveal ourselves. Of course, this didn’t start with the web. It was brewing since we said goodbye to our Victorian reserve. Early celebrity magazines like “Tattler” and “Hello” both served and punished those who featured in them; congratulating the rich and famous on their weddings, and publicly pillorying them for their excesses and social faux pas. But the exposé talk shows of the 80′s, with their cast of families falling apart, people coming out on live television, the spectacle of humanity in its ugliest moments, etc. brought this push for full public disclosure to a fevered pitch. The formula being that if celebrities are people whose lives are fully exposed, then we can all be celebrities if we fully expose ourselves. And this is formalized in the structure of reality TV and taken to its limits in the spectacle of self-made amateur porn.

Meanwhile, the tragedy of 9/11 and the growing sophistication of electronic means of surveillance, allow states, in the name of keeping us safe from harm, access to our communications, data transfers, stores of privately held information. Edward Snowden’s revelations about what the NSA has been doing have been met with, for the most part, ambivalence. For every person who complains that they no longer have privacy, five people respond that ‘If you don’t have anything to hide, this shouldn’t bother you.’

It’s for our own good. Our safety. We are told, patronizingly, that public confession is good for our souls. Get it off your chest. Tell us all about it. Blog it, tweet it, put it on Facebook. Reveal your innermost secrets, desires, dreams and we will… marketize them. The internet runs, financially, on user-generated content. And so we must encourage users to generate content and we do it by making self-exposure a civic duty.

I’m sorry Michel Foucault is not alive. I think he would have some valuable insights on what has happened to our culture in the last 20 years. He had some interesting things to say about surveillance; extrapolating the ‘panopticon’ model of Victorian prisons to the culture at large. For the most part, it is not necessary for those in power to keep us in line. We watch and judge each other. We model correct behaviour to each other, and never more so than now that we do it online.

We continue to protest that our sexuality is repressed, and yet we talk about it constantly. We flaunt our fantasies and our desires, and our self-exposure is reinforced by the accolades we receive for doing so. And the more extreme those desires, the more attention we get for having them. As long as we perform them publicly… and someone makes some money out of it.

For those who don’t expose themselves, there is always the shadowy, pseudo-legality of ‘those who keep us safe from terrorists’ who can pry into our emails, our telephone calls, our servers and our harddrives. If you refuse to be a public spectacle, we will ensure you know that you are still watched, still overseen by those who purport to have our best interests at heart.

No matter how anonymous you try to be, no matter how much think you’ve covered your tracks and separated your ‘real self’ from your online persona – I feel very confident in assuring you that you are not safe. If it is of benefit to someone to discover your real name, your home, your job… they can and they will.

Perhaps, truly, there is only one great transgression left. That of obscurity.

December 12, 2013

Knotted

I dream him in knotted clumps, caught in the tangle of puzzled occurrences. Wedged between the pages of books on how to just get through this one next moment. He has taken the one page I need in the phrasebook of a foreign tongue. He comes to me as a man in a hurry, a woman in denial, an old wizened hag weighted down with too much knowing, a child with big eyes full of inexplicable whims, serrated like plastic knives at a late summer picnic.

But I always know it’s him, looking out from those eyes. Hey there, stranger, I say. And the spectre grins and gives me a wink. How do we play this one out? Let’s see how it goes. There is no resolution to the nightly glass bead game. Different rules, different places, another obstacle course.

The obstacle used to be getting to him. Now the challenge is to get through to dawn. To break the surface at a place where time and space matter.

December 1, 2013

Pork Satay With Peanut Dipping Sauce

Things on Sticks. Streetside satay bar in Yangon, Burma.

This is another one of those posts that should probably go on another site, but in the interests of not being one-dimensional, here’s my recipe and guide for Pork Satay with Peanut Dipping Sauce. You can download it in PDF, ePub or Mobi (Kindle) format. Right-click to save to your desktop.

PDF version

ePub version

Mobi (Kindle) version

November 27, 2013

Extremist Sites and Rape Porn: Fear and Disgust and our Mindless Reactions

Mr Cameron is targeting websites which show videos and images of rape – whether they claim they are ‘simulated’ or not.

The prime minister has previously attacked websites which show the material, saying: ‘These images normalise sexual violence against women – and they are quite simply poisonous to the young people who see them.’ (“Rape Porn,” Metro.co.uk)

My response:

Mr. Cameron: these sites do not normalize violence against women. If they normalized it, people wouldn’t find it erotic. It’s erotic because it’s transgressive, i.e. not normal. And if you really cared about what is poisonous to young people, you’d reconsider issues of school fees and student loans. Because ignorance, Mr. Cameron, is far, far more poisonous to young people.

Fear and disgust are deeply wired mechanisms. Visceral reactions to the things we don’t like, things that scare us. I don’t deny anyone their right, as a human – as an organism – to react, to recoil, to turn away from the things in the world that trigger these reactions.

It’s the very common secondary knee-jerk reaction I object to: the equally almost instantaneous, equally mindless need to quash, kill, stifle, smother or ban the object of disgust or fear. And I object to a media that almost wholly validates this secondary reaction. They revel in it, they profit from it, they luxuriate in the serve and return of irrational spectacle that erupts from it.

I’ve spent many years, as a writer, creating stories that attempt to interrupt the mindless snowball that can result from that first reaction of disgust. I don’t want to make my readers like something they find disgusting. I just want to encourage them stop and consider what lies at the root of that fear or disgust, and consider what is really going on, in them, at the moment of that reaction. I try to do this as responsibly as possible, while still respecting that my readers are intelligent adults. I know I am going to offend and lose some of them. I know that some are going to plunge unflinchingly forward. What really interests me are those readers on the edge of the fight or flight knife.

I wrote the short story “Click” for this purpose. I don’t ask my reader to see the protagonist in a sympathetic light, although some might. I don’t ask people to be turned on by the non-consensual sex in the story, although some will be. Others will be instinctively disturbed and disgusted by it. It’s not a story that romanticizes or eroticizes rape or excuses it. And I’d have to wonder at the ethics of anyone who doesn’t find the story at least a little difficult to read. It was certainly difficult to write.

All I wanted to do in that story is carve a moment of thought, a minute of silence and consideration, for the complexity of the chain of events and for the readers own instinctive, emotional reactions to them. No one in their right mind would excuse ‘Carl with a C’; he’s a rapist. He’s a miserable, fucked up man with a mountain of existential anger that makes him dangerous and cruel. But I did want to invite my reader to pause and consider how he got there. Not to forgive him, just to understand.

Let me be really honest: I don’t like ‘rape porn’. I don’t like porn much, period. I can see how, for many women and men, rape porn might trigger a visceral, instantaneous reaction of disgust. It might even trigger both arousal and disgust. But the fact is that this is NOT REAL. The actors are consenting, the sex is consensual. The ‘rape’ part of rape porn is a fiction. And in the very few instances where what is offered is a documentation of a real crime, there are plenty of existing laws to prosecute that.

I understand this, and still I don’t like it. I think visual rape porn is problematic. Unlike text, which requires the reader to actively construct the imagery in their minds and by its nature engages whatever filters the reader requires, still and moving images are mentally processed differently. Those filters and that active participation are not required in the same way.

And so… I don’t watch it.

Yup. That’s it. I. Don’t. Watch. It.

Simple as that.

No need to make laws. No need to ban it.

If you don’t like it, don’t watch it.

If you do watch it and are shocked or disgusted or offended. Please feel free to be, and pledge never to watch it again. You don’t need to go that extra step and ban it just because you have a visceral reaction to it. Your urge to ‘keep the world safe from it’ is not a rational one; it’s a product of your very valid, very unreasoned visceral reaction. Yes, yes, I know it may FEEL like you need to stop the rest of the world from seeing it. But you don’t.

And just before you grope for another justification to ensure the thing that just disgusted you is never seen again by anyone, I’d like to remind you that there are a lot of heterosexuals who have this exact same reaction to homosexual sex. And no, I’m not equating gay porn with rape porn. I’m simply pointing out the problem. Our visceral knee-jerk reactions of disgust are uncontrollable. How we act upon them IS controllable, and we should act based on real threat, not imagined threat.

There is no significant data to argue that porn of any sort causes rape. There is, however, significant evidence that fictive, eroticized rape serves as a metaphor for a host of very complex psycho-sexual issues. I’ve got a post coming on that.

November 25, 2013

Make Better: Critical Writing Friends and Process

I am very fortunate to have two excellent supervisors for my PhD. My primary supervisor oversees my theoretical and critical work, my secondary supervisor acts in the spirit of a critical friend. She reads the work I’m producing for the creative part of the PhD, and gives me very good, very deep critiques.

I thought I’d pass on our process, because I think it is a very creative relationship. I’m pretty sure the institution is not paying her enough money for the time and thought and focus she puts in to reviewing the creative writing efforts of her students. This is something that money can’t buy. The friendship, which one is taught to prize above money, is not with the writer, but with the work.

A Room With A View

To begin with, after she reads the piece, she gives me her ‘reading of it.’ This is an excellent humanities-based version of a checksum. A ‘do you see what I see’ process in which she, as a reader, tells me what she believes the story means and what my intentions as a writer were. This is a very fertile way to start the criticism process because:

You know if you’ve really missed the mark in what you were aiming for (boo); or

You’ve created a very layered work that can have a number of interpretations (yay).

Discerning the difference is a matter of honesty and an understanding that every reader brings their own life-experience to the work they read, and this will always colour the interpretation. However, honesty on the part of both reader and writer are necessary and, being, for instance, of Caribbean descent, she lets me know when something in my story brings up strong cultural resonances or divergences. This is critically important. You need to know how someone from another culture will read your work. That doesn’t mean you have to tailor it to their culture – only be aware of it. On the part of the writer, you need to be honest about what your writerly intentions are.

So, if you end up with opposite understandings of the text, then you have a problem. The writing is not good enough. If, on the other hand, the critics reading agrees broadly with yours, but their interpretation adds another dimension, then you’ve got a good thing happening. Every reader is going to ‘see’ the story through differently tinted lenses, but if what they’re seeing is something completely different, you haven’t succeeded in your aim.

The Importance of Being Ernest

Next, she examines her reactions to the characters. She does this by asking questions about them. When I answer those questions, she will either say something like: “Yes, this is also how I see him/her” or “Really? I read him/her differently.” Very often the issue is what is motivating the characters. And this will depend greatly on whether or not this character attracts reader ‘investment’ and how. ‘Investment’ doesn’t mean a reader has to like a character, but they do have to care about what happens to them. It’s good to know if you have reader investment or not. If you don’t, you haven’t succeeded in creating an interesting enough character. I have to say, I see this a lot in erotic fiction. If all I’m offered is a character who just wants sex, they’re disposable. Most of the world wants sex; It doesn’t make them special.

Something Fresh

Then she looks at the language, line by line. She will catch almost every moment where I’ve lowered my guard and lapsed into laziness: where my metaphors or similes are cliche or stale and unevocative, hyperbolic or just uninteresting. Where I’ve used an adverb because I couldn’t be fucked to find a better verb. Similarly, she calls me out on dialogue that doesn’t ring true. Places where, for instance, I’ve let the necessities of the plot eclipse the truth of my character’s personalities. Sometimes she’ll point out a sentence and, without giving me any suggestions, simply say, “Make better.” I know what she means. I appreciate that she isn’t trying to re-write the work herself and that she trusts my judgement to know when I’ve been lax. I just needed it pointed out to me. Given the head’s up, I can indeed “Make better.”

The Time Machine

Finally, she is very honest about the pacing of the story. She notes exactly where her attention starts to wander. She’ll say – paragraph five, take out a sentence. The pace is lagging there. This is a very hard to take but critical part of the process. Writers have a tendency to think that everything they’ve written is necessary to the whole, but boring your reader is probably the worst thing you can do. Of course, there will be readers who simply aren’t interested in the subject of the story at all. That’s different. If they ARE interested, but you lose their attention, you haven’t written tight enough.

This isn’t an easy process, but its value is immeasurable. You now know what you’ve got on your hands and what you need to do to make your piece stronger. The proviso in all of this is that you both care more about the work than your own egos or opinions.

Novel Relations

Setting up critical friendships is hard. You want someone who can be a stranger to your work, and you can be the same to theirs. You want to be able to come at the work without preconceptions of conventions or modes. A reader outside your immediate genre, but with eclectic reading tastes is best. Remember, this isn’t about making your work more salable, but simply making it a better piece of writing. You’ve got to be prepared to say: “I don’t understand.” This isn’t about who’s clever. There are different levels of dedication to writing. Some people do it as a hobby. Some write simply for masturbatory reasons. Some write because it feeds their ego to get praise for it. I am not a good critical friend for that person. I will expect more willingness to work, to rethink, to rewrite than they are willing to give. Pick someone whose level of commitment to their craft is similar to yours and who you respect. That way, every piece of feedback you give or get is going to be appreciated and considered and, if it is discarded, you will know that it is done for good reason and not out of pique.

As a writer, you have to be proud of what you write. You have to be happy to associate your name with the piece. Ultimately, the decision to act upon or ignore a good piece of criticism is yours alone. As it should be.

November 23, 2013

Say it ain’t so: when reality doesn’t accord with our beliefs

I’ve spent a lot of this week collecting references for some papers I’d like to write. One attempts to challenge the very pervasive belief that being aroused by fiction sexually, emotionally, sentimentally or fearfully is somehow fundamentally negative – that it impairs our judgement completely and renders us quivering idiots (no, that’s not quite how I word it in the paper). The other seeks to defend the seemingly indefensible: the eroticization of fictional depictions of rape. So, I’ve been collecting a lot of papers, research from a wide set of disciplines. I’ve also being paying more attention to debates I’ve, until recently, had little interest in.

Take the debate that porn leads to rape. The more porn, the more easily accessible it is and the harder-core it is, the more it will influence people and cause them to rape. Well, no. This turns out not to be true in the general population. In fact, several large scale studies in various countries indicate that the opposite is true. (D’Amato, A. (2006). Porn up, rape down. Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series.). In a significant survey of many of the studies done on this topic, Ferguson puts it thus:

Real world rape data clearly does not support the belief that pornography contributes to rape in a negative sense. Rather data in the USA, Europe, and Japan supports the catharsis hypothesis that pornography is inversely related to rape. However, as this data is correlational in nature it is not possible to make a causal attribution

(Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Pornography. In Adolescents, Crime, and the Media: A Critical Analysis, Advancing Responsible Adolescent Development (pp. 141–158). New York, NY: Springer New York.)

A study done specifically on the effects of pornography consumption on sex offenders ( Mancini, C., Reckdenwald, A., & Beauregard, E. (2012). Pornographic exposure over the life course and the severity of sexual offenses: Imitation and cathartic effects. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(1), 21–30.) suggests that adolescent exposure to porn has some correlation to levels of victim harm, but that,

…although findings from the current study support the view that pornographic exposure (during adolescence) can lead to increased victim harm, little conclusive evidence exists to support the view that pornography use consistently impacts an offender’s propensity to become violent during a sexual attack. On the contrary, findings from this study also highlight null effects—that is, offenders who viewed pornography during adulthood did not inflict significantly more more violence during the crime. Not least, results indicate as well a potentially beneficial, cathartic effect—offenders who used pornography immediately prior to the offense were significantly less likely to physically injure their victims.

We now have some very useful data. Exposure to porn doesn’t cause people to rape, but there is a correlation where adolescent exposure is concerned. This gives us good guidance: we should not let our children watch porn. That’s good to know, since most responsible parents do their damnedest to limit their children’s exposure to it anyway. However, the study doesn’t say that adolescents who watch porn become sex offenders. It says that sex offenders who’ve been exposed to porn during adolescence are affected. This is still cor-relational, not causal. There are very probably a lot of reasons why people become sex offenders, and it would be foolish to heap all the blame on porn, or even a small portion of it. We know this because, over the centuries and all across the globe, people have been raping other people since time immemorial, and very few of them have been exposed to porn at any age.

Although data shows that rape rates are coming down (D’Amato, 2006), people have refuted the veracity of this data by arguing that it is based on reporting rape, and that perhaps levels of reporting have gone down. However, this is an argument that cuts both ways. It could very easily be argued that reporting has gone up, since being a victim of rape is no longer as socially stigmatized as it once was. In the absence of any evidence that there has been a dramatic fall in reports of rape in the past 25 years, I will take the good news.

Now, if we could just widen the effect of whatever it is we’re doing and exert some influence on places like the Democratic Republic of Congo – which at the moment seems low on democracy and sky high on incidences of horrific and violent rape – we’d be even better.

But… many won’t. I’ve encountered a very shrill, insistent dismissal of research results in some of the ‘rape culture’ discussions I’ve come across. These voices are well-intentioned. They believe passionately in trying to keep women safe from harm. They are fighting for a world in which women have better lives. And it’s not as if they are making a fuss over nothing. Women are getting raped. There are many, many women the world over living awful, miserable lives. But how does doggedly clutching on to a belief that may not be true help these women? There are reasons why men rape and why women, proportionally, are treated so poorly in society. It’s important to find out the real causal factors and deal with those. But my suspicion is that porn is an easier enemy to take aim at than the real ones. The social and psychological mechanisms that allow one person to see another as a non-entity whose feelings don’t matter, whose life doesn’t count, whose success should be feared are probably very complex. They were around long before even photographic pornography began. We’ve been treating each other like shit for centuries.

On an equally emotive and contested topic, a large longitudinal study (11,000 participants) has just been published on the psycho-social effects of TV and video games on children. (Parkes, A., Sweeting, H., Wight, D., & Henderson, M. (2013). Do television and electronic games predict children’s psychosocial adjustment? Longitudinal research using the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Archives of Disease in Childhood.) It turns out that there is very little, only on TV watching, not game playing, and only when children watched 3+ hours of TV per day.

I’m not a huge fan of porn. I find it facile, artificial and annoying. Similarly, I find video games – especially the really violent ones – disturbing. Intuitively, I would have thought that porn might cause some men to be more likely to commit rape. Intuitively, I would have thought spending hours shooting shit up on a videogame would make children more violent. It would be gratifying to believe that my aesthetic judgement is borne out in statistics that show how evil these things are.

But it turns out my intuition is wrong, they’re not. And personally, I’m happy to hear this, because it means that we aren’t doing awful shit to ourselves consuming this stuff. What disturbs me is the number of people whose agenda so depends on these results being different that they simply discount them and ignore them and keep on repeating and disseminating blatantly false information.

And if you thought this had any political stripe, you’d be wrong. Because there are literally millions of people who refuse to acknowledge that global warming is causing a rise in sea levels, even when the scientific data is overwhelming. (Bulkeley, H. (2013). Cities and climate change. Routledge.)

I don’t think simple confirmation bias explains this. I think people become dogmatic about what they want to believe, what seems ‘right’ to them, and they weave it so deeply into their lives that to consider they might be mistaken or working without valid information threatens their sense of self and sometimes, even, the purpose of their lives.

I guess the purpose of this post is just to say that although there is nothing wrong with questioning the data that science provides, it is also equally important to question ourselves. Why do we want something to be true/not true? What is our emotional investment in the debate and is that getting in the way of accepting new information and reconsidering our earlier assumptions?

Because if we cannot do this, then what is the point in having a debate at all? What is the point in using data at all, if the aim is only to gratify our egos by being ‘right’.

November 17, 2013

Pleasure’s Apprentice

Above the venerable silver shop in the Burlington Arcade, he taught her the uses of pleasure. Not the nervous-handed, spring-loaded fumblings of teenaged lust, or the ego-abraded outcomes of young love. Mr. Pierce offered Rebecca schooling in something quite different.

After quitting an English degree halfway through the first semester, alienated by the prospect of having to read and deconstruct ‘Waiting for Godot’ in French for the sake of authenticity, Rebecca Holloway found herself, both directionally and financially, at a loss.

Near Earl’s Court, she rented a drab bedsit with diurnally cyclical smells. In the morning it inevitably stank of burnt toast. At midday it was redolent with the smell of bleach. And, by nightfall, every rental room in the house was infused with the ghost of overboiled cabbage.

Having only ever had a Saturday job selling trendy clothes for pocket money, the possibility of full and gainful employment was daunting, but a lowering of expectations and a careful scanning of the ads in the evening newspaper paid off. Within a week, she found a position as silver-polisher and part-time shop assistant at Holmes & Sons Silversmiths in an arcade just of Bond Street. It was neither her previous work experience nor her successfully completed ‘A’ levels that got her the job. It was the fact that her antiquarian father had taught her how to decipher hallmarks and how to tell solid from plate—a skill she hadn’t dreamed would ever come in handy.

There was, of course, no Mr. Holmes or Mr. Holmes junior. The business’ name and stock had been sold on long ago to another proprietor with a less auspicious surname. The Ms. Patel who interviewed her made it clear that Rebecca’s chief job was to assist Mr. Pierce in polishing the silver as it tarnished, make minor repairs and otherwise remain scarce. She was only to be seen on the shop floor at the morning and afternoon delivery of tea to the sales persons, and during the lunchtime lull when the sales assistants took their lunch. Otherwise, she should remain invisible on account of her dyed-purple air and the ring in her nose, which didn’t bring the right ‘tone’ to the establishment.

The low-ceilinged room above the shop was dark. Light crept in from two small windows that let out onto the upper levels of an arcade that was almost Tudor in age. Night and day, summer and winter, the workspace was lit by a string of bare bulbs that ran down the ceiling of the tunnel like room. The walls were unevenly plastered in that way you only see in black and white movies, and down one of the long walls stood a massive set of shelves groaning under the weight of row upon row of old silver. Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, Art Nouveau and Deco. There was no new silver. Holmes & Sons had ceased to be silversmiths long ago. Now they were the Aladdin’s cave of everything your mother didn’t want to have to polish. Roughly in the centre of the room was a long, wide wooden worktable, half covered in newspaper, and laden with all manner of silver objects in need of attention. There were two chairs, opposite each other at the table, reminding Rebecca of the sort you saw in paintings of old school houses. Wooden, upright and mean.

In this domain—Mr. Pierce’s preserve—he showed her how to set out the silver tea service, place the spoons onto the china cups and saucers in rigid gridlike order. On first meeting him, Rebecca thought he would have made the perfect butler in a murder mystery; he was a tallish, thick-set man of about fifty, with a pale complexion and graying hair cropped close to his skull.

His eyes were grayish blue and held a look of perpetual disinterest. He seldom spoke in sentences, and preferred to pass on his knowledge by showing rather than explaining. It was an approach he took to everything, Rebecca was later to learn.

The first day on the job, he sat at the large wooden worktable across from her and watched in solemn taciturnity as she polished teapots, salvers, trays and flatware. Then, he repolished every item again. At ten thirty sharp he prepared the tea and gave her the huge, rattling tray to take down the narrow stairs, carpeted and threadbare, that lead to the shop floor.

“They’ll have finished,” he muttered, at eleven, and sent her back down to retrieve the tea tray.

In turn, Rebecca sat and watched him as he tied an unnecessary apron around his waist and carefully washed the tea things at an ancient stone sink in the corner of the room.

She had never met a man like Mr. Pierce. His existential economy of words, of movement, of expression fascinated her. Her father had been a nervous and excitable man with a penchant for over-dramatizing the banal. Her boyfriend in secondary school had been loud, sporty and prone to fits of temper. The lover she’d taken at university—a fellow student —had been melancholy and furtive, one moment bemoaning the injustice of the justice system and the next demanding proclamations of undying love. Mr. Pierce was a very different sort of man.

At first his silence intimidated her. He never told her she was polishing the wrong way. He simply polished it again. After a week of this redundancy of labour, Rebecca gathered up the courage to express her frustration.

“Mr. Pierce, if I’m not doing it right, tell me how you’d like it done.”

This elicited a single word. He reached over the table, took the Victorian sterling milk jug from her hands and said: “Watch.”

In the afternoons, Mr. Pierce would do repairs at the other end of the worktable. With torch, goggles and gloves, he would solder handles, spouts and knops back into their places. He would reset hinges and unbend ornamentation. After hours of sitting and watching, Rebecca asked if there was anything she could do, and was told she could read him the newspaper while he worked. On Thursdays, they sat together in silence and listened to the horse race reportages on an old brown melamine radio, used solely for that purpose, it seemed. Other times, it glowered silently at her from its spot on the shelf between the racks of flatware and the decorative picture frames.

Only after three weeks did Mr. Pierce allow her to make the tea. He supervised her in silence as always and, once she’d settled the teapot onto the tray, he nodded his approval.

“You’ll put me out of a job, lass,” he said, and indicated with a nod of his head that she could take it down to the shop.

Rebecca very much doubted there was anyone with the balls to consider firing Mr. Pierce. And it was with an inexplicable glow of pride that she carried the tea tray down to the sales staff.

In retrospect, Rebecca attempted but failed to comprehend how, as time went by, her world contracted by inches, until the pattern of it was unbroken only by weekend visits with old school friends and the occasional trip to the cinema. Her life became a badly lit cycle of evenings spent reading in her bedsit, days in the workshop and the commute between the two. And equally incomprehensible was why it didn’t bother her. Even as she watched it happen, knowing it was happening, there didn’t seem anything unnatural in it. What mattered was that the tea was made correctly, the silver was polished properly and the public library was still open by the time she got off the bus after work. Her phone never rang, and the small portable television that came with the room offered her nothing that engaged her attention.

Then, one day, almost three months after her arrival at Holmes & Sons, something happened.

Having retrieved the tray at 3:30 pm on a chilly November afternoon, Rebecca went to the stone sink and began to wash up. She stood at the sink, washing out a cup when she heard—or rather felt—Mr. Pierce step behind her.

“Aren’t you forgetting something, lass?”

She glanced down to watch his arms reach around her waist. He placed one hand on her lower stomach and moved her back from the sink and against his big body. With the other, he draped the drab green apron around her and, smoothing it flat, he stepped away and tied its strings tight about her waist, leaving behind the mixed scent of lead solder, silver polish, and masculinity.

The moment was electric. Her hand holding the china cup shook. Blood rushed up her chest and climbed the sides of her neck, making her skin burn. Her nipples stiffened into a sudden, awful ache. At her cunt, she felt a blossom of heat and then the creeping wetness seep into the crotch of her panties.

And that evening, having reached her cramped, shabby bedsit, she pulled of the still-damp panties, flung herself onto her single bed, and masturbated her way to a panting, sobbing orgasm. She came with an intensity she had never experienced before. Not that she’d ever come with anyone else; neither of her lovers had had the skill or the inclination to uncover the mysteries of a body she hardly understood herself.

Why Mr. Pierce had elicited this extreme reaction was unfathomable. Rebecca only knew that he had. And so, at eleven the following morning, once she had brought up the tray and prepared to do the washing up, she knowingly and deliberately did not put on the apron. Sponge in one hand, dirty cup in the other, she stood at the sink apronless and waited.

The water from the faucet was icy. Her fingers numbed. But, after what seemed to Rebecca like an inordinately long pause, she felt him come up behind her, and do exactly what he’d done the day before.

“Forgetful, are we?”

“Yes. Sorry.”

But she wasn’t sorry in the least. All she could feel was his massive hand moving her into his meaty warmth and the efficient tug of the apron strings as he crossed them around her waist and tied them at her back.

Did that hand linger just a little longer over her belly? Did he take just a little more time in smoothing the apron in place? Did he tug the strings a little more snugly than he had the previous afternoon? The intensity of her arousal and the fog in her head made it impossible to know for sure.

It was Thursday, race day. The radio’s nasal drone gave out the progress of the horses as they sped around the track at Kempton, as Rebecca came upstairs with the tray and set it by the sink. At first, she thought that Mr. Pierce was so engrossed in the narrative, he probably wouldn’t notice as she washed the cups. But, having left off the apron, she set about her task. As she began to soap the second cup, she felt him behind her again.

This time he said nothing. All she heard was a slow long exhalation. The hand again, encircled her waist, settled itself just below her navel, and eased her back from the sink, against his body. But instead of moving to wrap the apron around her, he left it there. His heat seeped through her blouse, her skirt. And her body, realizing this was a breaking of the pattern, set her heart thundering in her chest. He pressed harder and she heard him inhale. The breath was uneven and stuttered as he drew it.

It seemed to Rebecca that he held her like that for an eternity, but it couldn’t have been more than a few seconds. She had the sensation that somehow, she’d just stepped of a ledge and into thin air. It lingered until, with her ass pressed tight against his hips, she felt the slow and strangely frightening press of his cock as it came alive.

With his free hand, he covered her breast easily. At first the pressure was warm, gentle, but it grew into something demanding and raw. He squeezed until she squirmed, and, when she did, his other hand pushed down the front of her skirt, massive fingers wedging into the space between her legs and cupped her roughly.

Rebecca had been so worked up even before Mr. Pierce had touched her that she almost came apart in his hands.

“Put down the cup, lass. Turn off the water.” His voice was soft, almost inaudible above the radio’s drone.

Unsteadily, she lowered the cup into the sink and shut off the ancient faucet with a shaking hand. He held her there, letting her feel his erection throb against the clothed cleft of her ass. The hard metal of his belt dug into her backbone as she did what she was told.

Then, without any warning, the grip on her breast eased and the hand at her groin disappeared. He took her shoulders, moving her away from the sink.

“I’ll wash up today,” he said and, without glancing at her, stepped up to the sink and began to soap the cups and saucers.

For a moment, Rebecca stood in stunned silence, searching his impassive profile, glancing down at the dishes, and then back up at Mr. Pierce.

“Go on then, there’s all that Georgian flatware to be seen to. Don’t stand about.”

It was the most he’d ever said to her. With her heart still racing, and her body still wanting, and the echo of his fierce hands on her flesh, she returned to the table, sat down and finished her work.

Once the race commentary was over, Mr. Pierce switched off the radio, and they worked in silence until five-thirty. As her body cooled down and the hush stretched out, a sense of shame replaced the arousal. Only when he followed her through the darkened interior of the closed shop and let her out the door, locking it behind them, did he speak.

“It’s not a game,” he said, his stern, grey eyes meeting hers as he pocketed the keys and pulled on a pair of gloves.

“No,” she replied, unable to move in the pin of his gaze.

His face softened and he reached up, swiping the side of her cheek with a gloved finger. “You’re awfully young, lass. Find yourself a nice young man.”

There was no way to say what she wanted. She only knew that she did want, and with a terrible ferocity. Rebecca turned and fled down the arcade as if her body would burst apart into a thousand pieces if she didn’t use it to run.

Friday morning found Rebecca in an only slightly calmer state. She had hardly slept the night before. All she could see when she closed her eyes was the old stone sink, the running faucet, and the cup shaking in her hand. All she could feel was the overwhelming need Mr. Pierce engendered in her. All she could remember was the brief enormity of his touch. No one had ever held her with such purpose. For those fleeting minutes, when her body had quivered like liquid, she had never felt such a sense of being possessed in her life.

Throughout their morning work, she felt Mr. Pierce’s stare. He watched everything she did. And under that unrelenting gaze, she dropped salvers and spilt polish and fumbled the simplest tasks.

“Take it down,” he said, when the morning tea was ready.

She was sure she’d drop the tray as she brought it into the shop. And as the minutes ticked by, from ten-thirty until eleven, a great battle raged in her mind. But when she walked back up the stairs with the empty cups, she had decided.

Very deliberately, she put the tray beside the sink. And very deliberately she turned on the water and squeezed a generous amount of washing up liquid onto the scrubber. And very deliberately, she began to wash the dishes without the wearing the apron.

Mr. Pierce had watched her the entire time, from his seat at the worktable. He didn’t move.

“Lass, put the apron on,” he said softly.

Rebecca didn’t glance at him. She stared down at the saucer in her hand and washed it with a furious purpose.

“Put it on.”

His voice was close, but she didn’t look up. Her blood was singing with an eerie defiance. Her flesh was on fire. Inside, muscles fluttered wildly, and the crotch of her panties was sodden with need.

Hardly touching, Mr. Pierce reached around her and turned off the tap. He covered her hands with his and guided them down to the bottom of the sink. She let the plate clatter to the stone and dropped the sponge.

“Good lass.” It was a soft, whisper close to her ear.

Without releasing them, he guided both her hands to the thick, rough lip of the sink and forced her fingers to grip it. Then he let them go.

“Don’t move. Not a word. Not a sound,” he growled.

The hands settled on her waist and then moved upwards, big and sure. They took her like territory. As they covered her breasts, she flinched and heard his breath hitch. He was behind her, breathing hard, one hand groping her right breast while the other unbuttoned her blouse and pulled it open.

He didn’t bother to fight with her bra, simply tugged the cups down and the straps dug and burned at her shoulders as he took a breast in each hand and squeezed them. His big, rough fingers burrowed into her skin.

At her back, she could feel the want bleed from his body. His hard on pushed into the roundness of her ass, ground it against her and unsteadied her, he growled again.

“Not an inch. I told you.”

Rebecca gripped the sink, steadied her body and closed her eyes. She clamped her mouth shut to stifle the moan that she was sure would emerge unbidden, but it was like trying to stop boiling water from bubbling.

His hands moved down, leaving her nipples throbbing. They paused to grip her hips and hold her steady as he rubbed against her, before one snatched at her skirt and pulled it up. Fingers raked up the nylon of her stockings and past them, over bare thigh, and covered her sodden mound.

He made a noise, soft and low in his throat. “Is this for me, lass?”

The contact made it impossible to be still. Rebecca rocked her hips, drove herself against the hand at her crotch. “You know it is.” It came out like slurry.

Was it for him? For him specifically? For a man more than twice her age who never flirted, never wooed her, hardly spoke? And did any of that matter once she felt him tug her knickers down her thighs, once she heard him unbuckling his belt, unzipping himself? She listened to his trousers, keys in the pocket, slither and drop to the floor.

The way he moved her to his liking, the delicious heat of him when he pushed his cock between her thighs and angled himself so expertly for the first, deep thrust. The way he bent over, bending her too and braced himself against the same cold stone sink with one hand, the other clamped over her mound.

She had been so ready for him, for what seemed like so many days. When he finally took was she was offering, it only took half a dozen thrusts to detonate the bomb inside her. As if he’d done this many times before, he knew, and shushed her as she came on his cock. And so what should have been a cacophony of pleasure came out as a stream of choked off whimpers.

“Good lass,” he panted. “Give me another.”

The hand that had steadied her pubic bone moved, fingers searched out and found her swollen clit. He coaxed it with each inward thrust, so that each felt like a stubborn door being battered open. And it was impossible to refuse him what he asked for.

He fucked her methodically, meticulously. Rebecca could feel the ridge of his cock head as he withdrew almost completely before plunging home again. If he was worried about being caught fucking his assistant, he didn’t fuck like he gave a damn. He fucked like he did everything else: quietly, carefully, thoroughly, until she broke again in shudders and sobs locked up in her chest.

Only then did he come. As if he’d been waiting to see that she’d done the job properly before moving on to the next step. It wasn’t quick or furtive. He just stopped thrusting and erupted into her cunt, letting her feel each hot spurt flood her passage.

Then he withdrew, pulled her panties up roughly and put his trousers back on.

“Stand up, turn around.”

With the lassitude that comes from orgasm, Rebecca straightened herself and watched, mutely, while he repositioned her bra, and buttoned up her blouse.

“Lots of work waiting. Better get to it, now.”

* * *

In the days that followed, Rebecca learned a lot. Mr. Pierce taught her how to clean off broken pieces of silver, coat the sheared edges in flux, and solder them back into place.

He also taught her how to please him. His huge hand wrapped around hers as she stroked his cock, using her saliva and his precum to make it slick. He showed her when he was ready for her, on her knees, looking up at him, to cover the head with her mouth and staunch the flood that resulted.

“Don’t make a mess, lass,” he said.

He showed her how to ride him as he sat on one of the two schoolroom chairs. How to let him use her body the way he wanted, to relax as he guided her hips up and down. How to stifle her cries against the side of his neck when she came so hard from his use.

Bent over the worktable, he taught her to lie still and silent and let him plunder her cunt and her ass with his fingers, his cock and his mouth.

He never kissed her. Never said words of love to her. Never asked her out or did any of the things that lovers do. All he ever offered her was the pleasure of being possessed by him in that drab room above the shop. She never learned his first name.

When, a year later, she left Holmes & Sons to have another go at a university degree, she left knowing exactly what her body could do, and with an unnatural reaction to the scent of silver polish.

Stone, Memory and Want

There is a specific jouissance to being denied what you need. An ecstasy to it that comes to define you. It describes you as a potential, as a flawed thing, undeserving of the thing you want, incomplete for now.

I am the piece of meat that circles around the whirling blades. Nicked but never ground into the paste of the whole. The drop of water that never quite makes it down the drain to join the sea. And after a while, that simple act of missing the boat becomes the work of a lifetime. The familiar landscape of the imperfect vortex.

Perhaps today I wouldn’t think it much of a mountain but, at the age of seven, it towered above me, rocky and steep and seemingly impossible. In the hills above Ojen, my father handed me a glass bottle of water in a string bag, and fitted his own into his knapsack.

Perhaps today I wouldn’t think it much of a mountain but, at the age of seven, it towered above me, rocky and steep and seemingly impossible. In the hills above Ojen, my father handed me a glass bottle of water in a string bag, and fitted his own into his knapsack.

“Come on,” he said, beckoning with a strong, brown, vein-lined hand. “We can get to the top by lunch.”

Rock and scrub. Dry red earth and grey-green brush, hunkered down against the mountain from the sun and wind. We climbed: my father with his long, dark, muscular legs and I on all fours. I scrabbled up the incline like a badly nurtured feral child. Succeeding only when I stopped thinking and let my body do what all small creatures try to do, I gave in to the instinct to climb to safety.

The young, ferocious sun reached its needle-like fingers through the weave of my shirt and pricked me. The rock crumbled in my hands, under my summer-bleached Keds. My long black hair caught in the thickets of dead bushes and dry leaves, stuck to my face and my neck in the rivulets of sweat, its salt stinging in the crevices of my limbs. The dust smelled of sharp things and tasted like a penny on my tongue.

He strode ahead. His legs taking him easily over the jagged rock, up the steep grade of the mountainside. A god immersed in his own inner dominion. His lips moved as he climbed. He was writing in his head. Lost to the mountain and the sun and the wind and to me. I knew I was following the physical incarnation of a god whose mind was elsewhere, as it often was. Gods have important things to think about.

Even if I had to reach the summit like a baby, on my hands and knees, I would do it. I would not fail my father. I would not disappoint him this time. I would not give him another reason to think less of me.

Not like the last time, when he had taken me out to sea on the pedalo, and I’d fallen in the water while he was thinking. It had been a long dog-paddle back to the beach through a forest of medusa tendrils.

That’s what you get for not keeping up with a god. The sun reminded me of the burn of those thousands of tiny, jelly strands against my skin and climbed faster.

The bottle swung in my string bag. Bumping against my hip. My thigh. Water sloshed in the bottle. It’s sound so alien in that landscape. It’s inner coolness condensing on the glass. Droplets pattered into the dust, leaving a trail from the sea up that mountain. The incontrovertible evidence of my propensity to fail him on my heels, I climbed faster.

He did not talk as we ascended. But the rocks spoke to me: hard glottal stops and crumbling dusty whispers until we reached the line of dry, misshapen pines, bent tight to the hillside just like me. Then the needles and the cones spoke in thick, tight patterns of order and disorder. The morse of sparse shade and the half-finished sentences of roots grown free from the earth. The acrid scent of old sap and sweetness of wounded wood where the beetles ate their way through the crinkled, scaly bark.

I lost my footing and slid backwards into the bowed trunk of a tree. For a moment, all I knew was fear and the exhilaration of the almost something worse than the big, black ants I’d disturbed. They crawled in wavy, black rivers over my fingers where I clutched onto trunk.

“What’s wrong?” he demanded.

“Nothing. I’m okay. I’m coming.”

“No. You’re not okay.” He towered above me, looking down at my leg, and I followed his gaze. “You’re bleeding.”

I was. I’d gashed my ankle on something as I’d slid. Perhaps a rock or a root.

“It’s okay. It doesn’t hurt,” I said, pulling myself up.

“Stay there.”

“But there’s ants.” I watched two shiny black ones skitter through the blood on my foot, leaving two little lines of red as they climbed up my shin.

“Stay there!”

My father edged his way down to me, dust and dead pine needles shifting under his feet. He crouched by my leg, pulled a glaring white handkerchief from the pocket of his shorts and, after brushing off the ants and dabbing at the cut, tied it tight around my ankle. It had looked like a flag of truce until I bled through it. Then it just looked like a bandage.

“You’re fine,” he said.

“I know.” Even though by then the shock had caught up to me and I was on the verge of tears.

“Drink some water.”

I stood up, did my best not to panic as I brushed the rest of the ants off me, and pulled my bottle of water free from the string bag. It had one of those metal and rubber stoppers – bright red and white – and made a popping sound as I flipped the wire back and opened it. Before I drank, I watched him to see how much was the right amount to drink.

Jaw up, head back, he drank. His Adam’s apple jumped as he swallowed, perhaps a quarter of the bottle. So I did the same. The water was warm. It pushed the tears back down my throat. That’s why he never cried, I realized. He had that Adam’s apple to keep the tears from coming up. Lucky.

“Let’s go. We’re almost there,” he said, glancing up the rocky incline. He wasn’t lying.

It wasn’t long before we clambered up and out onto a flat area, barren but for one bent, gnarled pine. Beyond it, in the glaring distance, lay the flat cobalt slab of sea, a rock of a different colour. Above it, the hazy blue belch of sky rose from a long roll of cloud on the horizon.

I sat cross-legged on hot, speckled granite, but my father stood and slowly turned. He closed his eyes, spread out his arms and inhaled, sucking the sky down into his chest.

“Shut up,” he murmured, eyes still shut. “Don’t say anything. Don’t spoil it.”

It was a view. It was perhaps the reason why the mountain was there – to bring that view into being. I think only adults can love views. At seven, once I’d taken it in, there was no more to drink. It was big – big as the world -and beyond my ability to absorb it. But under the crippled pine, in the shade of its tortured branches, was a small pile of stones.

It wasn’t terribly tall. It only rose up to just above my knee. A pyramid of smooth, rounded rocks. Some had writing in chalk on them, others were pitted and bare. Some had been scratched with something – maybe another stone – like cuts into its hard, dark skin, the pale heart of the rock showing through. It was my father’s shadow that blunted the glare of the sun and allowed me to see that they were letters. Words. Names. Initials. And tucked between the rocks, yellowing, tattered folds of paper. I pulled one out and opened it. There was writing in pen, but so faded I could not read it. So I folded it back up and put it back.

He swung his pack off his shoulder and rooted inside it, pulling out a little spiral-bound notebook and a pencil. Leafing through it, he tugged on an empty page and handed it to me with the pencil.

“Write something.”

I took the paper and pencil and squinted up at him. “What should I write?”

He clicked his tongue in frustration. “Look around you, you idiot. You’re here, on the top of this mountain, in this incredible place. Write something. Something that matters.”

I squatted in the shade and thought. Something that matters. What could I write that would be big enough to fit on that page? Big enough to be fit for the purpose? There, on that summit, with my father the god, a whirlwind of dust at his feet, and the sun waiting on me to find the right words.

I wouldn’t know what to write now. I had even fewer words then. So I pretended to write something. I used the pencil to echo the patterns the pine needles had made, the whorls of bark on the trunks, the purposeful trails of gleaming black ants, the angles of the rocks, the crackled lattice of dried mud I saw on the way up.

My father held out his hand. I knew he wanted to read what I had written, but I couldn’t let him see. I folded and refolded the page until it was a small, tight little square and gave it to him. He didn’t open it. Perhaps he didn’t want to be disappointed. I think he knew that, whatever was on the paper, it wasn’t something he would have given me any praise for so he chose to postpone that deeper silence.

We hunted for some nice round stones and, after snuggling my illegible, wordless note between two kissing rocks, he carefully placed the new ones on top of the existing pile. The breeze stilled, the dead branches ceased rustling against each other, and the cicadas stopped keening. For a few moments, my father, the mountain and the world stilled. I knew it was to let me know that my failure had been duly noted.

“Right, let’s get a move on,” he said, standing from his crouch. “It’s a long way down.”

* * *

He’s in Highgate now, sandwiched between his selfish bitch of a mother and his criminally irresponsible father. There was just enough room between them to slot him in. None for the rest of us, and that’s probably all to the good.

This is about as far from the hot, dusty mountaintop above Ojen as either of us could get. It’s overcast. Drizzling and cold in the way only England can be. It reaches beneath your clothes, no matter how many layers you’ve put on, and snatches at the warmth like a spiteful, bitter urchin.

I’ve come to talk to a headstone. Something I’ve only recently realized has any value. I wasn’t here for his burial. I didn’t believe in those things then. I always thought it was my duty to carry him around in my heart. The whole clever, cruel, skilled, manipulative, rotting mass of him. I’ve wandered through the world, traveled to almost every continent, gone to bed each night and awakened each morning with the black hole of him inside me. Sought out his echo in every lover I’ve had. Treasuring the ones who would not or could not give me what I needed and despising the ones who tried.

Over the years, I’ve grown to love the sublime exile and the ritual denial of whatever it is I am so certain could complete me. Perhaps it was lost in the sea off the coast of Malaga and wedged among the rocks on that steep climb up to the mountaintop above Ojen. Other places, earlier places, too. Or perhaps I just need to believe that it must once have existed and once been found because the wound is so indescribably deep and needs a reason to exist. My failure to find it defines me.

I thought that what I needed was praise from him. Praise he couldn’t give me, praise I didn’t deserve. There was no praise to be had. And perhaps that’s the clue. I’m almost certain now – that wasn’t it. It just served as a convenient marker for some amorphous impossibility we’ve passed down through the generations, like a disease.

“Did you take that deep breath on the mountain because you knew that one day you’d end up here?” I ask the headstone. “Was it big enough to last all those years?” I don’t have to ask the dark anymore. I can speak to this piece of granite and leave his answers behind when I go.

I have failed brilliantly, again and again, to write something important. It took me almost half a century to understand that there are moments when it’s hubris to think there are words – any adequate words – to mark the occasion. Out of my purse, I retrieve the tightly folded blank sheet of paper, place it on the headstone, and pin it there with a smooth, round rock.

November 8, 2013

Silken Tofu with Ginger Syrup

Yes, this has nothing to do with erotic fiction. But you know, I do other stuff too. I wrote up this recipe for a friend. It’s downloadable in PDF or Kindle version.

Yes, this has nothing to do with erotic fiction. But you know, I do other stuff too. I wrote up this recipe for a friend. It’s downloadable in PDF or Kindle version.

Silken Tofu with Ginger Syrup

PDF document

Epub document

Kindle document