Michael Estrin's Blog, page 20

November 20, 2022

Homeward bound: 1 horse, 2 boats, 2 planes, too many cars, and a humbling farewell

I’m writing this dispatch from the Manila airport. If Dante’s ghost ever gets around to doing a sequel to The Divine Comedy, I think this place is in the running for the tenth ring of hell.

Sorry. I love to travel, and I love the Philippines, but as I write this, we’re twenty hours into our long journey home, and we’re looking down the barrel of a four-hour layover, followed by a thirteen-hour flight to Los Angeles. The only upside to this madness is that we leave Manila around noon Monday, and arrive in Los Angeles at eight in the morning also on Monday. Time travel!

Our journey home began Sunday morning on Gili Air, when a man with a horse-drawn cart came to pick us up and take us to the pier.

I tipped our driver, then tried to tip the horse, but that caused some confusion. Maybe there was a language barrier???

I tipped our driver, then tried to tip the horse, but that caused some confusion. Maybe there was a language barrier???At the Gili Air pier, I spotted a 24-hour Halal shawarma stand that looked promising, but we didn’t have time to eat because we had to catch a small boat to Lombok.

Unfortunately, there were no shawarma stands at the Lombok pier, where we waited for a “fast boat” to take us back to Bali. But the really bad news was that the fast boat’s engine kept getting clogged by trash because humans treat Earth’s oceans like dumps. A boat trip that should’ve taken three hours ended up being closer to five.

The SS Not-So-Fast

The SS Not-So-FastOur flight from Bali was scheduled to leave at one in the morning local time, but since we’re flying Philippine Airlines, our flight was delayed for no reason at all. Thankfully, we had booked a hotel near the Denpasar airport, so we could shower, nap, and grab a bite to eat. Which is what we did, except that Christina napped, and I didn’t. But I did go for a swim in the hotel pool, before binge-watching the BBC’s wall-to-wall coverage of the World Cup in Qatar. If you’re wondering, FIFA is Latin for whataboutism.

Just before midnight, we left for the airport. I took a picture of the van that picked us up, but I’m not going to bother including it in this post because vans are the same the world over, unless we’re talking about Van Life on TikTok, which is a subject for another post.

ANYWAY, I sort of had this idea that this dispatch would include a picture of each mode of transport on our journey, but on the five-minute ride to the airport something profound happened, and now I’m going to tell you about that instead.

The man who came to pick us up at the airport was the father of one of our guides. Our guide, a man named Ocha, had wanted to take us himself, but he had a family obligation that somehow didn’t involve his father. Ocha said it was a birthday. His father said it was a wedding. There may have been a misunderstanding there. But that’s besides the point. The point is what Ocha’s dad said to us.

“I want to thank you for coming to Bali,” he said. “Do you know why I say thank you?”

I was going to say something along the lines of, because you have a beautiful island full of lovely people, and really, everyone should visit Bali because it’s awesome. But it turned out that Ocha’s dad was asking a rhetorical question.

“I say thank you because tourism is the only resource Bali has. We cannot grow enough to export. We do not manufacture. We are tourism.”

Comments like this were a recurring theme on our trip. Tourism is the number one industry in Bali. But Bali isn’t a wealthy place. Indonesia is a developing nation; in term’s of GDP per capita, Bali ranks 19th out of 34 provinces. The GDP per capita on Bali is about $10,600 per year.

Ocha’s father might’ve dwelled on the fact that Bali’s prosperity is tied to the people from wealthy nations who choose to vacation there. If I were in his flip-flops, I’d probably dwell on that, and let’s face, I’d be bitter as fuck. But he wasn’t going to dwell, and I couldn’t detect an ounce of bitterness. In fact, the only emotion I picked up on was gratitude—not the kind some influencer sells on social media, but rather the genuine article. Gratitude with a capital G. And I think what Ocha’s father said next explains where that gratitude comes from.

“My village had no electricity when I was young. No plumbing. In 1969, when America goes to the moon, the chief of my village rings the bell, and we go to the temple, and he tells us America is on the moon. And we all look up at the sky—WOW!”

As someone born at the tail end of the Generation X cohort, every Boomer I’ve ever met can tell me where they were when John F. Kennedy was killed and where they were, just six years later, when our nation fulfilled our President’s promise to go to the moon. Many of those Boomer recollections are moving, but none have moved quite so much as hearing about the moon landing from a man who witnessed a giant leap for mankind from an island in the Indian ocean that hadn’t yet made the leap into the twentieth century.

Photo by NASA on Unsplash

Photo by NASA on UnsplashAs we pulled up to the airport—a modern airport that puts LAX and Manila to shame, by the way—Ocha’s father made one last point about the distance he and Bali have come in the decades since humans first walked on the moon.

“For my parents and my brothers and sisters life is very hard. Very hard. I work at hotel pool. Hand out towels. Tourists teach me English. A tourist gives me a book to learn English. I learn English to make life better. I teach English to my son. His life is better than mine. That’s why thank you for coming to Bali.”

Actually, thank you, Bali, for having us!

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali edition of Situation Normal! If you’re new here, subscribe to receive one last Bali dispatch & lots more slice of life humor👇

November 18, 2022

Gili Air is chill AF and the snorkeling rules

After our escape from the mischievous monkeys of Ubud, we needed to chill the fuck out. Thankfully, the final leg of our journey takes us to an island called Gili Air, which might just be the most chill place on Earth. But first, a few words about our driver, who might just be the hardest working teenager on Bali (HWToB).

On the two-hour drive from Ubud to Padang Bai, Christina felt a little car sick, but HWToB and I talked the entire trip. HWToB told me that he was just finishing his final year of high school.

“I drive a few hour in the morning before school starts, and I drive after school too. Sometimes I do other jobs too, like in a restaurant, or help my family farm. I also take care of my parents. They’re old. I’m the youngest. My brothers all work on cruise ships.”

“How’d you get this job?” I asked.

“My uncle works for the fast boat company. They need drivers, and I can drive.”

“Will you be a full-time driver after you finish school?”

“No. I’m studying Korean so I can work in Korea.”

“What will you do in Korea?”

“I’ll work in a factory. The money is way better than here. My Korean is not good, but I just need it to be good enough to pass the exam so they’ll hire me in Korea. When I get there, I’ll use English. Everyone in the world speaks English. It’s how you get ahead. Also, YouTube is better if you know English.”

“How long will you stay in Korea?”

“A few years. I want to make some money, then come home and buy land.”

“What will you do with the land?”

“Live on it, start a business.”

“What kind of business?”

“Something that makes money.”

“So by the time we come back to Bali, you’ll own the place, huh?”

“No. Well, yeah, maybe. I hope so. But first I have to pass my Korean exam.”

Switching gears, I asked HWToB if he had ever been to the Gili Islands.

“No. But they’re beautiful. It never rains there.”

“Never?”

“Never.”

“And they’re Muslim, right?”

“Yeah, they’re part of Lombok. Lombok is Muslim, like the rest of Indonesia. But they’re chill. Lots of parties and beaches. Drugs too.”

“I thought drugs were illegal in Indonesia?”

“They are. But there are no police in Gili, so drugs are legal.”

I wasn’t sure HWToB and shared the same definition of “legal,” but I let that slide. I wanted to know what else he had heard about Gili Air.

“No cars. You walk, you bike, or you take a horse.”

We had heard about the horses. When we booked our hotel, they told us that a man with a horse-drawn cart would meet us at the docks.

“They don’t have dogs there because dogs are haram.”

OK, so dogs were out, but drugs were in. Sort of. This had to be the weirdest interpretation of Islamic law I had ever heard of.

“They have cats, but the cats have no tails. Also, no plastic. Well, they try to avoid plastic because it’s bad for the environment.”

When we reached the fast boat, I gave HWToB 300,000 rupiah, about $20. He looked shocked because that is a huge tip in Bali, where tipping is appreciated, but not expected. I told him it was a thank you for a great conversation and to put the money toward his bulgogi fund. He told me he was going to watch some YouTube videos to learn about bulgogi.

As we took the two-hour fast boat from Bali to Gili Air, I considered what I had heard about our destination. Everything HWToB told me about Gili Air tracked with what other Balinese people had told us about the island. But none of the Balinese people we met had actually ever visited Gili Air, or its sister islands, Gili Meno and Gili Trawangan. Because I want these dispatches to be more than just hilarious encounters with monkeys and beautiful travel pictures, I made a mental list of claims to verify on Gili Air.

No cars

No rain

No dogs

No plastic

Cats are cool, but their tails are out

Drugs are a maybe

Within thirty-six hours of arriving on Gili Air, I busted several myths. First, it does rain here. In fact, there was a really solid downpour our second night on the island. Second, the cats here have tails. But the claims about cars and plastic are accurate! Both are bad for the environment, the locals say, and so both cars and plastic are unwelcome. Our hotel also bans beef because of the “cow farts.”

One of the many horse-drawn carts on Gili Air

One of the many horse-drawn carts on Gili AirAs for the drugs it’s hard to say what the deal is. Some of the people getting on the boat at Gili Trawangan looked like they had come from one of Thailand’s full moon parties. If they didn’t manage to score coke, ecstasy, and magic mushrooms, I’ll come back, dunk my Dodgers hat in a bowl of sambal, and eat it. Here on Gili Air, the drug scene is chill. I’m positive I could buy weed, but there’s no way in hell I’m buying weed where my only defense is that HWToB told me it was “legal.”

Regarding all the other vices you might think are forbidden on a Muslim island, this agnostic, cultural Jew is pleased to report that Gili Air’s top three priorities are as follows:

Have fun

Have fun

Have fun

The only local woman I’ve seen wearing a hijab was also in charge of collecting the island’s 10,000 rupiah entry fee at the dock. You can get booze anywhere, anytime. When I asked a hotel staffer about modesty, he told me that it was only necessary for women to cover their legs at Hindu temples. Then again, our hotel pool has designated skinny-dipping hours. Also, the local boat captains have filthy minds, as evidenced by the names they give their boats. A few fan favorites:

SS Mama Gets Wets

SS Sex Machine

SS Fuck

The boat names gave us plenty to laugh about when we chartered an unnamed boat for a snorkeling expedition on our first full day.

Our first stop took us to a reef just off the shore of Gili Trawanga. We saw thousands of colorful fish, but the sea turtles were the highlight. I don’t know what it is, but there’s something magical about watching sea turtles doing their thing. It’s like a moment of Zen wrapped inside a warm hug.

Christina also got a great video of a sea turtle ascending toward the surface for some air. Sound on!

But climbing back onto the unnamed boat, Christina banged her leg on a ladder that, frankly, wasn’t ship shape.

“Welcome aboard the SS see you next Tuesday,” Christina said.

“Is that see, or sea?” I asked.

Christina enjoyed the pun, but she took a pass on our second stop, the underwater statues at Gili Meno.

A word about the statues. Initially, I thought they were the ruins of some ancient civilization—Lombok’s answer to Atlantis. But then I turned to Google, and Google rained on that parade.

The statues, which guide books typically describe as “haunting” and “beautiful” are actually an art installation by Jason deCaires Taylor. The piece, which features 48 life-size figures standing together and curled up on the ground, was commissioned by a luxury resort. The idea is that statues, which are made from eco-friendly material that won’t mess up the ocean, will grow coral, and hopefully, grow business too.

Before I jumped into the water, Christina gave me a quick course on how to use our GoPro. Then she remembered that she was speaking to someone of limited technological ability.

“I’m setting it to take stills,” she said. “Just point and shoot.”

“Got it.”

As soon as I jumped in the water, I realized two things. First, like all Instagramable tourist attractions, Meno’s underwater statues are a clusterfuck of amateur photographers jockeying for position so they can do it for The Gram. Second, the current is so strong that you need to kick and stroke really hard just to maintain position, while using all of your power to actually reach the statues.

After recording an epic workout on my Apple Watch, I reached the statues. I wanted to take in the beauty of an underwater art installation, but that just wasn’t in the cards. Instead, I focused on maintaining my position, dodging other swimmers, and snapping as many photos as I could.

“How’d it go?” Christina asked when I got back to the boat.

“I took a lot of photos, but I’m not sure what I got.”

Then I handed her the GoPro, along with a disclaimer.

“If I’ve got shots of people’s butts and crotches, that wasn’t intentional,” I said. “The current was so strong, and it was a total clusterfuck, so I just snapped photos like crazy.”

Christina checked the GoPro. I had indeed shot some X-rated underwater photos, but Christina deleted those. Then she picked the best unobscured shot and posted it on The Gram, naturally. Then I asked her to send me the original photo so I could share it with you!

Gili Meno’s Underwater Statues. Photo credit: Michael “the accidental porngrapher” Estrin

Gili Meno’s Underwater Statues. Photo credit: Michael “the accidental porngrapher” EstrinWe had planned to visit another snorkeling spot, but we cut short our voyage on the SS Sea U Next Tuesday.

Back at our hotel, Christina took an Advil for her leg, and the pain went away. Late in the afternoon, we walked out on the beach, and ordered some food and drinks. Then we hung out with the other guests and the hotel staff to watch the sun set over Gili Meno and the mountains of Lombok.

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali (Gili Air) edition of Situation Normal! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

November 16, 2022

Escape from monkey mountain

After more than a week in Ubud, we thought we had the local monkeys figured out. We did some “research” while visiting Ubud’s Monkey Forrest. We chatted with hotel staff about the monkeys. And in the afternoons, while waiting out the day’s rain, we observed the monkeys from the safety of our room.

Here’s a photo taken from our balcony. When the rain stopped, a troop of monkeys would descend from the trees to forage for food and look for opportunities to create mischief.

The monkeys would always begin and end their foraging expeditions by cutting across the grass. The child in me was excited to see them, because I love monkeys! But the old man who lives inside me couldn’t resist the temptation to grumble, get off my lawn, monkeys!

But not all the monkeys stayed on the grass. The bigger, bolder, boss monkeys would demonstrate their leadership bona fides by leaping onto our balcony and looking for an unlocked door or window. Evidently, bringing back minibar snacks to the monkey troop is a good way to maintain your status. Come to think of it, the wild monkeys of Ubud aren’t all that different from the U.S. Congress insofar as their operations resemble a clusterfuck, mischief is par for the course, and bringing back some sweet, sweet pork—or in the case of the monkeys, some candy bars—is a must.

But a monkey in your hotel room is dangerous, which is why the hotel staff instructed us to keep our doors and windows locked. From the behind the safety of those locked doors and windows, Christina and I spent many happy hours observing the monkeys, giving them names, and snapping photos.

Randy “Toblerone” Mardukas

Randy “Toblerone” MardukasSeveral hotel staffers told us the monkeys always come out in the afternoon. Since this tracked with our observations, we called the afternoons “Monkey Happy Hour.” But for some reason—wishful thinking, logical fallacy, stupidity—we assumed that the monkeys only came out during Monkey Happy Hour. As it turned out, we were dead-wrong.

On our last night in Ubud, Christina and I returned to our room to pack. In the distance we heard the sound of a lonely frog.

“That’s weird,” Christina said. “We’ve heard all kinds of jungle sounds, but this is the first frog.”

We listened to the frog as we packed. Then we listened to the frog some more as we got ready for bed. Then, as we read our books and tried to drift off to sleep, we listened to the frog some more.

“That mother-frogger is gonna go all night,” I said.

“How do you know?” Christina asked.

“I’m reading a book about frogs.”

“Really?”

“No. I’m reading a book called Dead in the Water: a True Story of Hijacking, Murder, and a Global Maritime Conspiracy.”

In the distance, the frog let out a long, baritone croak.

“That mother-frogger,” Christina said.

We turned out the lights and tried to sleep. We had an early call the next day in order to make the two-hour trip from Ubud to Padang Bai, where we planned to catch a fast boat to an island called Gili Air.

In the morning, we woke up about fifteen minutes before my alarm. It was still dark outside, and the frog was still making that croaking sound.

“It’s funny,” I said. “Every morning we’ve been here, we wake up to jungle sounds. Mostly birds, I guess. It’s like a lovely chorus. And at night, there are different jungle sounds, but also a lovely chorus.”

“But that fucking frog,” Christina said.

“Did you get any sleep?” I asked.

“Not much.”

“Me neither.”

“What do you think that frog wants?” Christina asked.

“What all frogs want. Someone to kiss them and turn them into a prince.”

“I think that’s a fairytale.”

“OK, fine, the frog wants to get fucked. It’s a mating call.”

“Well, someone out there needs to fuck that frog. Do you think he kept the monkeys up all night?”

“Maybe. But probably not, though. They’re probably used to having a horny, unfuckable frog for a neighbor.”

We showered, got dressed, then idiot-checked the room to make sure we didn’t leave anything behind. Then I called the front desk to see if they could send someone to help with our bags.

A few minutes later, a friendly man came to take our bags. We stayed behind to use the bathroom one last time before hitting the road.

“I think we’re ready,” I said.

“Farewell Ubud.”

We slung our backpacks over our shoulders and stepped toward the door. The open door.

“Monkey!” Christina screamed. “Holy shit, it’s a monkey!”

Just then, I saw a monkey—a big, bold, boss monkey—looming in our doorway.

“Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!”

Immediately, our flight-or-fight mechanisms kicked in. Mine went with flight because I am a coward. Christina’s went with fight because she is a badass.

Panicked, preparing to die, and willing to piss my pants, but for the fact that I had just emptied my bladder moments prior, I ran as far away as I could. Unfortunately, our room in Ubud was quite small, and after seven lightning-fast steps, my back was to the wall.

Meanwhile, Christina executed a tactical retreat with the poise of a Navy SEAL. She took three steps back to assess the situation and look for a weapon. Grabbing a nearby umbrella that the hotel provides to shelter guests from the rain (and to fend off monkeys), Christina began to advance.

“Back! Monkey back!”

Christina swung the umbrella wildly, then banged it against the floor to make a loud sound in order to frighten the monkey.

“Back!”

“Don’t look him in the eye,” I screamed.

“Back, back, back!”

As Christina advanced toward the doorway, the big, bold, boss monkey retreated.

“Back!”

Then at the steps leading up to our room, the monkey paused, turned around to face Christina, her umbrella, and her wrath.

“Back!”

For a moment, the monkey held his ground.

“If he shows his teeth, run!”

I was repeating the monkey safety advice we had been given, but Christina had the situation well in hand.

“Fuck around and find, monkey!”

Christina swung the umbrella over her head, then brought it down on the stone pavement with a mighty crash.

A second later, the big, bold, boss monkey jumped down from his perch, tucked his tail between his legs, and ran back to his troop. I’m sure he didn’t want to explain why there wouldn’t be any candy bars for breakfast, but seeing Christina brandishing that umbrella, I knew that when the monkey told the story of the Assault on Room 218 he wouldn’t have to exaggerate the badassery of the woman who saved the fucking day.

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali edition of Situation Normal! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and hear about Gili Air, where there are no monkeys.

November 14, 2022

Now we're cooking!

As far as I know, there aren’t any Balinese restaurants in Los Angeles. But my knowledge in this area is limited. So maybe I’m totally wrong about that. Maybe there’s a Little Bali in some nook or cranny of Los Angeles I’ve never explored. But I’ve never come across Balinese food back home, and I’ve certainly never heard a friend sing the praises of a hole-in-the-wall Balinese joint they know. Come to think of it, I can’t name any Indonesian restaurants in LA, either.

Before we left, Kevin, my wife’s cousin’s husband asked me what people eat in Bali. I told him I knew they ate a lot of rice, and I thought they ate satay, but beyond that I didn’t really know.

“In Amsterdam, we had an elaborate meal called Rijsttafel,” I told Kevin. “The meal consists of, like, twenty little plates. All these different Indonesian dishes. But I’m not sure if that’s legit Indonesian, or more like what Indonesian people think Dutch people want to eat when they say, let’s go for Indonesian tonight. Kind of like how American’s love General Tso’s chicken, but Chinese people have never heard of General Tso or his chicken.”

But as soon as we arrived in Bali, I realized that I had eaten Indonesian food before. In Singapore’s hawker centers, one of my go-to dishes is nasi goreng. It’s fried rice with some vegetables, maybe some crispy chicken on the side, and a fried egg, plus peanuts. At the time, I thought nasi goreng was a Malay dish. Actually, it is a Malay dish, but it’s also an Indonesian dish, as well as something you find in Sri Lanka, Brunei, and of course, Singapore. Nasi goreng varies from one country to the next, but the variations are more about the spices that flavor the dish, whereas the core ingredients stay the same, I think. So, like I said, maybe I’ve had Indonesian food before, and maybe I haven’t.

If you’re confused by this back-and-forth, know that I too am confused. Consider the confusion a disclaimer, and please proceed with caution. Because initially I thought this trip would be about discovering Indonesian food, then as I learned more about Bali and its place in the Indonesian archipelago, I realized our trip was actually about sampling Balinese food. And then today, in an effort to further confuse my palate and my readers, we took a cooking course.

Our teacher was a woman named Batum. I asked her to spell her name because I didn’t want to half-ass this dispatch, but there was a language barrier, so Batum it is. Anyway, Batum was a great teacher.

We started with the ingredients, or as a fancy-pants food snob who binge watches all of the cooking shows might say, mise en place. Some of the ingredients, like shallots, garlic, and ginger, were familiar. Other ingredients like ginger flower, candlenut, and kencur root, aren’t things I’ve seen at Trader Joe’s, Ralph’s, or even Whole (Foods) Paycheck.

As we sliced and diced, Batum explained the situation that was about to unfold.

“First, we make Bumbu Bali,” she said. “It’s paste made with garlic, shallots, ginger, kencur, galangal, turmeric, shrimp paste, black pepper, coriander seed, candlenut, and red chili.”

“Wow, that’s a lot of stuff,” I said. “Do we blend it all up?”

“We use Balinese blender.”

Did you know the Balinese invented the blender? Only their “blender” is a hand-power tool called a ulekan, which is sort of like a mortar and pestle, only the mortar part is a shallow, circular dish about a foot in diameter.

The ulekan isn’t just a kitchen essential, it’s also a great workout.

The ulekan isn’t just a kitchen essential, it’s also a great workout.“Bumbu Bali is very important,” Batum said. “We put it in everything.”

I thought she was kidding, but she wasn’t. Bumbu Bali is kind of like Bali’s answer to curry paste, and it went into everything we made, even the corn fritters.

“Is corn a traditional Balinese ingredient?” I asked.

“Yes, Balinese love corn.”

I knew that was true. Corn fritters are always on the menu here, and every farm seems to have a section for growing corn. But as an amateur historian and confused foodie, I’ve been obsessed with a corn-related mystery on this trip. I always thought corn was native to the Americas. But of course, “native” is a tricky concept on a planet that’s been doing globalization, in one form or another, for seven centuries. What I was really asking Batum was whether the Balinese had corn back in the day, or if it came here more recently, maybe on sailing ships back when Bali was part of the spice islands, or maybe in the last hundred years, thanks to American influence? But I couldn’t quite get my question across to Batum, and I haven’t quite been able to get it across to the other Balinese people we’ve met, either. So for now, I’m filing Bali’s obsession with corn under ‘D’ for delicious and cross-referencing it under ‘U’ for unsolved.

Thankfully, Batum was able to clear up the larger mystery of Indonesian-Balinese food.

“We make both,” she said. “Some dishes Indonesian, some Balinese.”

Then Batum went on to explain that at this particular moment in Bali’s history, Indonesian cuisine and Balinese cuisine coexist, much like Hinduism coexists with the animism at the core of Bali’s cultural traditions. A good example of what I’m talking about was the last dish we made.

I cooked fried rice (Balinese), while Christina made stir-fried noodles (Indonesian). The ingredients—including Bumbu Bali, naturally—were basically the same, except for the starches. Also, we cooked the rice and the noodles in woks, which of course, come from China. But then again, the historical record suggests that the people of Bali originally came from China too, so maybe it’s best not to think too rigidly about what makes for “legit” cuisine.

Michael repping Bali. Christina repping Indonesia.

Michael repping Bali. Christina repping Indonesia. In the end, we made nine dishes. Way too much food! But we also learned a few tricks.

First, it pays to make Bumbu Bali in bulk. You can even freeze it for up to a month. That’s what Batum said she does because “you don’t have time to cook it every night, but you need it for everything you cook.” Meal prep, people, am I right?

Second, everyone has their own sambal recipe. Some like it hot, some don’t. “It’s like salsa,” Batum said. “You choose.”

Third, Balinese chefs have the perfect treatment for mosquito bites: shallots. At Batum’s urging, we rubbed raw shallot on our mosquito bites and the itching vanished! That’s a total game-changer for next summer at Casa de Michael & Christina.

But back to the food. It was amazing! Christina’s favorite dish was the fried rice. For me, it was a toss-up between the chicken satay on lemongrass skewers and the sayur urap (Balinese salad). Here’s a photo of our lunch. Ten out of ten would recommend!

Minutes after this photo was taken, the food seen here was decimated by two hungry amateur cooks named Michael and Christina.

Minutes after this photo was taken, the food seen here was decimated by two hungry amateur cooks named Michael and Christina.Of course, we couldn’t have done any of this without Batum’s help. But as we finished up, Christina and I realized that we might not be able to replicate what we’d made in our kitchen back home. We hadn’t written any of this stuff down.

“Do you remember the recipe for peanut sauce?” Christina asked. “What about the steamed chicken in banana leaves? How do we do that?”

“Don’t worry,” Batum said. “I give you recipes.”

Again, amazing! Now all I have to do is figure out how to source some of these Balinese ingredients. But then again, trade has been a central part of Balinese life for more than a thousand years, and I’m sure the world’s ultimate trader, Jeff Bezos, has some people in Denpasar ready to fulfill my Balinese shopping list.

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali edition of Situation Normal! If you’re new here, make sure to subscribe for free to receive new posts.

November 13, 2022

Balinese FAQ

I travel to learn, but the farther I go from home, the more likely I am to find myself in the role of a teacher. In Bali, that cultural exchange is fairly smooth because most Balinese people speak some English in order to work in tourism, which is the island’s biggest industry.

We’ve met plenty of Balinese people on our trip. None of them have been to the U.S., but all of them have questions about America. Typically, the first question we get is, how long did it take you to get here? When we explain that it took us two flights that should’ve taken about twenty-five hours, but ended up taking two days, the reaction is amazement that any trip could take so long and gratitude that we’d make such a long journey to visit Bali.

But after the initial travel question, the real questions begin. For this dispatch I thought it might be instructive to share the frequently asked questions of our hosts. Here it goes.

What do Americans do on the weekend?

Is it true that there are homeless people in America? Why don’t those people return to their villages and live with their families?

Does it snow where you are from? Does snow hurt your skin?

When is the rainy season in America?

How far from Los Angeles to New York?

Do you have a dog, or a cat?

Do you have a gun?

Everyone still loves Obama, right?

Does Arnold Schwarzenegger still run California?

When will there be a new Arnold Schwarzenegger movie?

Have you seen Eat, Pray, Love?

How big are your roads?

Have you been to Texas? What’s it like?

Will Joe Biden come to the G-20 in Bali?

Americans are Christians, right?

Are you on Facebook?

Have you seen TikTok?

How big are your mountains?

Do you have a motorbike, or car?

When did you get electricity?

Do you eat at KFC?

I was going to close this post with some pictures, but the internet is spotty at the moment, so I’ll leave you with just one picture from one of the many temples we’ve visited. Almost every temple, and many homes, have a structure like this at the entrance. It’s known as the Gate of Heaven.

If you go on social media, you’ll see some more photogenic examples, but I chose this one for two reasons. First, it’s a fairly typical example. Second, the sarongs wrapped around the statues tell you something about how the Balinese relate to Hinduism. Just like the humans visiting the temples, the gods must also practice modesty. But rather than carving sarongs into the stone, the Balinese wrap their gods in clothing as part of a larger practice of humanizing objects.

The gods must be modest.

The gods must be modest. Thanks for reading the Situation Bali edition of Situation Normal! If you’re new here, please subscribe for more stories👇

November 12, 2022

Temples, a wedding, a royal cremation, plus dessert

Tanah Lot Temple: a postcard for you and me, a way of life for the Balinese

Tanah Lot Temple: a postcard for you and me, a way of life for the BalineseBefore we left for Bali, I bought an audiobook called History of Bali: A Captivating Guide to Balinese History and the Impact This Island Has Had on the History of Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The title is long, but the audiobook is short—about three hours. Also, it’s part of a series from a company called Captivating Guide, but if I’m being honest, the audiobook is more interesting than captivating. I bought the audiobook because I wanted to level-up my knowledge in order to ask better questions while visiting Bali. Nerd alert.

By mentioning my extracurricular reading, I’m trying to sound smart, but in the interest of full-disclosure, I need to tell you that when it comes to Bali, I am dumb. Really dumb. I know, for example, that Indonesia is a Muslim country, but that Bali is majority Hindu. I know that the Dutch colonized the Indonesian archipelago, but I had no idea that this region—wedged between the mainland of Asia and Oceania—was once part of the Majapahit Empire, which included modern day Indonesia, as well as parts of Malaysia and the Philippines. And like any good Anthony Bourdain fan, I know that Bali is one of those places where the food tells the story of a cultural exchange that has played out over more than a thousand years.

But something I didn’t quite realize before coming to Bali was that this island, which is undoubtably influenced by the cultures that have come here to conquer, to trade, to convert, and to exploit, is above all else, unwaveringly Balinese. You could fill a library with books about what it means to be Balinese. I am in no way qualified to write any of those books. But the more Christina and I explore this island, the more I’ve come to understand that even the most powerful forces the world throws at Bali—religion, war, colonialism—can’t disrupt the essential nature of what it means to be Balinese.

That lesson came to me slowly over a few days, courtesy of our guide, Giri. On our first day together, I asked Giri what impact the Dutch had on Bali.

“Not much in the grand scheme of things,” he said. “The Dutch came to trade. They didn’t convert us to Christianity. Maybe they didn’t care, or maybe we didn’t care. Bali adapted because Bali adapts, but now the Dutch are gone, and we’re still here.”

“But before the Dutch, there were Muslim traders?”

“Yes, there are a few Muslims here, but mostly no. In Indonesia, yes, lots of Muslims. But in Bali, no.”

“So Hinduism is dominant?”

“Yes and no. We are Hindu, but…”

Initially, I understood the “but” as an asterisk, like how Catholics in Spain are different from Catholics in Ireland, but nonetheless, Catholic. But in Bali, religion hits different. A Hindu from India would recognize the gods, the customs, and the stories of Balinese Hinduism, but it’s not the same. Before Indian traders brought Hinduism to Bali, the Balinese practiced an animistic religion, and honestly, they still do. I’m not a theologian or an anthropologist, but in terms anyone reading this on the internet should be able to understand, the Balinese have their own hardware and firmware, but they’re currently running a version of Hindu software.

“The genius of polytheism,” Giri explained, “is that there’s room for everything—other gods, other ideas, other myths. We are Hindu, I think, because there’s room for Balinese traditions too.”

Those traditions, I’m learning, vary from village to village across Bali. At Goa Lawah temple, for example, Giri explained that he would have to wait outside.

“I cannot enter this temple because someone from my village died recently,” Giri said. “For other Balinese, they must wait three days, but my village, for some reason, we must wait ten days. The young people want to make it three days to wait, but the old people won’t change. I think when they’re gone, we’ll change that.”

Inside Goa Lawah temple

Inside Goa Lawah templeThe more we talked to Giri, the more we realized how central religion is to his life. But when I mentioned that to him, he rejected the word religion.

“Community,” he said. “Community is the word. That is what matters. That is how we live. We don’t necessarily believe the stories. They’re myths. But we learn the values. That’s what’s most important.”

We found out what Giri meant by community and values when we asked him if he could show us around the following day.

“Sorry, no. A man in my village is getting married.”

The groom wasn’t related to Giri and they weren’t really friends, but Giri explained, everyone in the village participates. Weddings, like everything else in the village, are a community project.

“I am security,” Giri explained. “We stand outside the wedding and direct traffic.”

“So you’re not invited to the wedding?” Christina asked.

“I am invited. He invited eight hundred people. I’ll go and sit with him for a little, eat some food. But then I need to be outside to help direct traffic.”

“Do people drink at Balinese weddings?” Christina asked.

“No. Well… the security drinks. We sit outside and drink beer while we direct traffic. It’s fun.”

We got the hint. The next day, we took time off from sightseeing, got massages, swam in our hotel pool, and with talk of weddings in the air, celebrated our eleventh anniversary at Room for Dessert, Will Goldfarb’s farm-to-table restaurant in Ubud, where guests feast on a twenty-one course dessert menu.

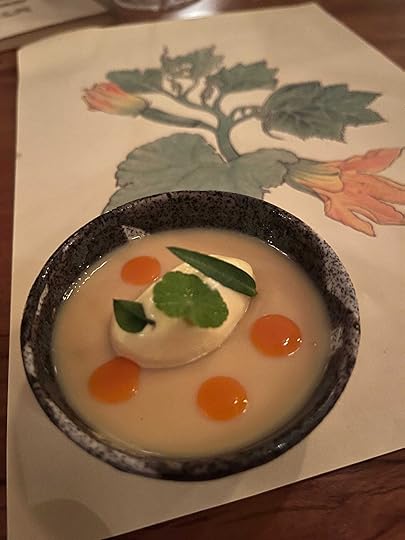

My favorite dish: sweet corn custard with chili oil.

My favorite dish: sweet corn custard with chili oil.The day after the wedding, Giri picked us up to visit some more temples. But as we pulled away from our hotel, he told us we were lucky.

“Why’s that?” I asked.

“A member of the royal family died and they will cremate him today.”

Luck didn’t quite seem like the right word, but Giri insisted that a couple of tourists stopping by wouldn’t be an imposition, or weird, or even sad. Also, he explained, the deceased was a member of the royal family of Gianyar Regency (the district where Ubud is located), and that there are a lot of royals in Bali, so it’s not like a really famous or powerful person died. Basically, it was just going to be a big-budget example of a Balinese cremation, which is the ritual for most—but not all!—Balinese villages when someone dies.

“If it won’t be weird, I guess we can go,” Christina said.

And so we went. And it wasn’t weird. Actually, it was beautiful.

The idea of the ceremony—which is known as Ngaben, Pitra Yadyna, or Pelebon, is to release the soul of a dead person so that it can enter the upper realm. Depending on how the dead person lived, their soul is either reborn, or liberated from the rebirth cycle. To release the soul, they burn a cremation tower known as a wadah.

A Balinese cremation tower. The community stayed up late the night before putting it together, and then they’ll burn it.

A Balinese cremation tower. The community stayed up late the night before putting it together, and then they’ll burn it.We were welcome to stay for the ceremony, but Giri explained that it would take all day. First, two hundred men carry the tower roughly two miles to the cremation site, then there’s praying, then they burn the tower, then everyone goes home, then the family goes to a temple in the mountains for a blessing, before taking the ashes to the sea.

There’s a lot going on here, and honestly, I’m not in any position to explain the rituals, let alone the meaning of the rituals. But what I can say is that it’s a good thing the whole community is involved because a Balinese cremation is a lot of work. It’s also something that impacts everyone in the community, even if they’re not directly involved in the cremation ceremony.

“The electric company is here,” Giri said. “Because the tower is higher than the power lines, they will cut the lines so the tower can pass.”

“They cut the lines?” I asked. “What about the people who need power?”

“They lose power,” Giri said. “But then they put a new line up right away. Maybe it takes thirty minutes, or an hour. No big deal.”

No.

Big.

Deal.

Where Christina and I come from, I’ve seen motorists honk at a funeral procession just to express their frustration at being delayed by a few minutes. Our neighbors don’t invite us to their weddings. And the temples are neither postcard-worthy, nor are they open for the community to use whenever they need to.

We come from Los Angeles, California, USA. Whatever it is we’re bringing to Bali, I get the sense that we’re just passing through, that Balinese who welcome us with open arms are happy to see what we have to offer, but if it doesn’t fit into their community, it won’t change Bali, not in any meaningful way anyway.

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali edition of Situation Normal! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

November 10, 2022

Monkey business in bat country

In Bali, it’s safe to assume that where there’s a forrest, there are monkeys. We learned this as soon as we arrived in Ubud, a mountain town surrounded by forrest. Our driver warned us about the monkeys. The woman at the hotel reception desk warned us about the monkeys. The man who helped us with our bags warned us about the monkeys. I don’t know if this is true, but I believe there’s a law here that compels the Balinese to warn every tourist they meet about the monkeys. Here are the warnings:

Monkeys will steal your shit, so make sure to shut the doors and windows to your room.

Monkeys will fuck with your shit, so make sure to keep your possessions in your pockets when in the presence of monkeys.

Monkeys will mess you up, so make sure to respect their space, avoid looking them in the eyes, and whatever you do, be prepared to back the fuck up if they show their teeth.

In theory, these warnings sound reasonable. But in practice, these warnings are difficult to abide because when you encounter monkeys they’re either too damn cute to keep at a distance, or too damn brazen to avoid. Our first monkey encounter was a case in point.

The other night, after snorkeling the wreckage of the USAT Liberty, we came back to our hotel to find two monkeys waiting on the steps leading up to our room.

“Oh my god, look at the monkeys!” Christina said. “They’re so cute!”

To be clear, the monkeys, long tale macaques, were cute. Really cute. But to me they looked like trouble.

“I think we should turn around,” I said. “This place belongs to the monkeys.”

“But this is our room. What are we gonna do, wait for the monkeys to leave?”

“Yes.”

We were both tired, and hungry, and in need of showers, but Christina was in no mood to wait.

“They’ll move,” Christina said.

But the monkeys didn’t move. The monkeys just sat there, blocking the stairs to our room. Then a second later, four or five more monkeys jumped down from the roof and joined their pals on the steps.

“It’s a damn monkey gang,” I said.

Christina took one more step, then froze. The monkeys were still cute, but clearly these monkeys meant business.

“Don’t make eye contact,” I said. “I’ll get help.”

Slowly, I backed away and found a hotel employee.

“Do you need turndown service, sir?”

“No, I need help. There’s a gang of monkeys blocking the entrance to our room.”

The man understand immediately. Seemingly out of nowhere, he grabbed a stick and told me to follow him.

As soon as the man with the stick arrived on the scene, five of the monkeys retreated. Obviously, those monkeys were cowards. But the sixth monkey, who was nothing to fuck with, held his ground.

Whap, whap, whap.

The man hit the first step three times, then advanced.

Whap, whap, whap.

The man hit the second step with the stick, then continued his advance.

Whap, whap, whap.

As soon as the man hit the third step, the monkey jumped up and scurried away.

“It’s safe,” he said.

And it was safe, for the time being.

But the next day, we were scheduled to visit the Ubud Monkey Forrest, a local sanctuary that’s home to more than 1,200 monkeys. Would these monkeys be trouble, we wondered? Would they steal my glasses? Would they jump on Christina and rip her face off? These were the questions that kept us up the night before visiting the Monkey Forrest.

In the morning, we turned to Google, a time-tested tool for amplifying fear. Christina found a story about how the monkeys of Bali had expanded their turf during the pandemic.

“A bunch of monkeys took over an entire hotel,” Christina said. “They were everywhere. They even started using the pool.”

For some reason that really shook us. We still wanted to see the monkeys because monkeys are adorable, fascinating, and endlessly entertaining. But as we pulled up to the Monkey Forrest, all we could think about was danger. As it turned out, however, the monkeys at the sanctuary were totally chill.

As soon as we arrived at the Monkey Forrest, a woman who worked there introduced herself and told us she’d be our guide. Like the man at the hotel, she carried stick, just in case. But she also carried a few bags of peanuts because monkeys love peanuts. In no time at all, we had these monkeys eating out of the palms of our hands.

We spent about thirty minutes walking around with the monkeys. None of the monkeys tried to steal our shit, or fuck with our possessions, or mess us up.

For a brief moment, one monkey got in another monkey’s face, but that was private monkey business. Then there was some very private monkey business, but I don’t think he was her type and a moment later, she ran off to join another monkey who was eating a pineapple. That was the only monkey drama. For the most part, these were family monkeys.

We were feeling pretty good about the monkeys, when our guide led us into the forrest. Since the monkeys sleep in the trees, I thought we’d see more monkeys there, but I was wrong. As it turned out, the forrest was bat country.

Just like the monkeys, the bats gotta eat.

A man we’ll call Batman told us that the bats eat fruit.

“Good for them,” I said.

“You hold one,” Batman said.

“Fruit?”

“No, hold bat.”

That was a hard pass for me. But Christina was game. She held a bat by its wings. Then Batman gave Christina a bottle and told her to feed the bat.

“Is that beer?” I asked.

“No, apple juice,” Batman said.

“Bats drink apple juice?”

“Of course.”

That sounded like some weird shit to me. But this was bat country, where weird shit is par for the course.

“Now, you feed the bat,” Batman said.

“No.”

“Yes.”

“No thanks, I’m good.”

“Feed.”

I could’ve said no again. Actually, I think I did say no again. Several times. But the next thing I knew, I was holding a bottle of apple juice in one hand and an upside down bat in the other.

I can’t say feeding the bat was fun because it was actually scary and weird and kind of icky. But eventually, we left bat country, and for that I am grateful.

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali editions of Situation Normal! Subscribe for free to see what happens next.

And if you’d be so kind, tell a friend👇

November 9, 2022

War and peace at the bottom of the sea

I read somewhere that anticipation helps us derive greater joy from our vacations. I don’t know if that’s true, or if it’s just clickbait some travel writer dreamed up to feed the content mill. What I do know is that I’ve been dreaming about today’s adventure ever since we booked our trip to Bali.

Whenever our travels take us anywhere near an ocean, Christina and I always ask the same question: how’s the snorkeling?

In Bali, the snorkeling is excellent. The water is clear, the conditions are usually calm, and the sea life is beautiful. But there’s one spot in Bali, about one hundred feet off the beach at Tulamben, that offers something unique for snorkelers: a shipwreck.

Usually, shipwrecks are too deep for a snorkeler to see. They’re popular attractions for scuba divers, but unlike Christina, I don’t dive. I’ve tried diving, and somehow I managed to experience agoraphobia and claustrophobia—at the same time! So, no diving for me. Which means no shipwrecks for me either, or so I thought. Because as it turns out, the wreckage of the USAT Liberty is perfect for snorkelers.

A little backstory. The USAT Liberty was a transport ship. It entered service at the tail end of World War One, transporting horses from the U.S. to France. After the war, USAT Liberty got into some shit. In 1929, it collided with a French tug called Dogue. The tug sank, killing two crew members. In 1933, USAT Liberty collided with the cargo ship Ohioan near the Port of New York. The Ohioan didn’t sink, but its crew was forced to beach the ship.

About a month after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the USAT Liberty was in the Pacific, tasked with transporting railway parts and rubber from Australia to the Philippines. About ten miles southwest of the Lombok Strait, the USAT Liberty encountered a Japanese submarine. But instead of colliding with the Japanese sub—USAT Liberty’s go-to move—the transport ship was struck by a Japanese torpedo.

The torpedo attack didn’t sink USAT Liberty, but it did force the transport ship out of the war and, eventually, into the tourism business. With the help of two other ships, the USS Paul Jones and the Dutch destroyer Van Ghent, the USAT Liberty made it to Bali, where its crew beached her at Tulamben. Some of the supplies were saved, but the USAT Liberty was a total loss.

The story might’ve ended there, and snorkelers like me might’ve been denied a chance to see a shipwreck, but twenty-one years later nature intervened. In 1963, a volcano called Mount Agung erupted, and the resulting lava flow pushed the USAT Liberty into the sea.

After two collisions, one torpedo attack, and two decades of rusting on the beach, USAT Liberty finally achieved its shipwreck destiny, and I got to see something I never thought I’d see!

The wreckage of the USAT Liberty

The wreckage of the USAT LibertyWe spent about an hour exploring the wreck. Without going below snorkel-depth, it was easy to make out the ship’s features, along with some of its cargo. I was fascinated by my first—and possibly only-shipwreck. But the more I explored, the more I noticed the fish, the coral, and the other sea life that has reclaimed the remains of the USAT Liberty.

A long time ago, the ship was built as an instrument of war, but today it is the foundation for a small community of life. I don’t know if that duality makes the USAT Liberty beautiful, or ugly. But seeing so much life thrive on a vessel of death, I couldn’t help but think that we are so very small, that our war to end all wars, and its sequel, and all the other destruction we bring upon ourselves is, in the grand scheme of things, a drop of water in the ocean of time.

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali editions of Situation Normal! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

November 8, 2022

Actually, it's the journey and the destination

It’s about nineteen miles from Seminyak to Ubud, as the crow flies. But we took a car, and cars in Bali use narrow, winding roads that are clogged with scooters, pedestrians, and anything else that moves. There are no traffic lights. To make a turn, the driver edges toward oncoming traffic, waves, then waits for the other motorists to let them pass. Our top speed on the journey was around thirty miles per hour. At one point, we got stuck in a traffic jam that was caused by the lunchtime rush at a really popular roadside chicken joint. The trip took about two hours.

As Angelenos, Christina and I are very familiar with traffic, although in LA the line at an In ‘N Out drive-thru, as opposed to a chicken joint, is often the culprit of our lunchtime traffic jams. But only tourists eat beef here, so chicken it is. Also, the traffic in LA has a grinding, soul-crushing feel. Here, the traffic is more like an invisible force field that slows everyone down and invites you to stop and look around.

On the road to Ubud, we stopped to see some women making batik fabrics. Christina bought a few meters of material. One pattern will likely serve as our tablecloth at Thanksgiving. After some YouTube tutorials, Christina plans to make the other pattern into some throw pillows, although for reasons that are unclear to me, I’m not allowed to throw them.

A few miles down the road, we stopped again to see some men carving wooden sculptures by hand. Their work is incredible, and they do it without the aid of a picture to guide them. Common sculpture subjects include monkeys, dogs, frogs, dolphins, and a big-ass Komodo dragon. There were also a variety of deities, including a ten-foot Jesus, skinny Buddhas and fat Buddhas, and Ganesh (naturally). We bought a wooden dragon mask because it spoke to us, and if I’m being honest, because we’re obsessed with HBO’s House of the Dragon. We thought about buying something bigger, like a giant wooden dong, but I didn’t want to have to explain that one to the customs agents at LAX.

Eventually, we made it to Ubud, a town high up in the mountains that many call the cultural center of Bali. Ubud will be our base of operations for the next eight days, so I’m hoping to learn more about the textiles and wood carvings we bought. I’m also hoping to see tons of monkeys because I fucking love monkeys, and Ubud is monkey central. Hopefully, I’ll also get to do some yoga because that’s big in Ubud. But for now, I’ll close with a picture of the view from our hotel.

Like I said, it’s the journey and the destination.

Somewhere in that jungle, lurk thousands of mischievous monkeys!

Somewhere in that jungle, lurk thousands of mischievous monkeys!Thanks for reading the Situation Bali edition of Situation Normal! Subscribe for free to receive new dispatches on the irregular.

November 7, 2022

Who wants to be a Balinese millionaire?

In Bali, it’s easy to feel like a million bucks. Actually, it’s more like a million rupiah, which is the local currency. At the moment, one U.S. dollar buys you about 15,500 Indonesian rupiah. The biggest bill I’ve seen is a 100,000 rupiah note—about six dollars in Yankee greenbacks. In practical terms this means two things:

We are Balinese millionaires

My wallet is stuffed

To help you visualize what I’m talking about, I took the money out of my wallet and, like a gangsta, threw my cabbage across the bed. Needless to say, Christina was impressed; she even started calling me Big Daddy Warbucks.

2.4 million rupiah, or about $150

2.4 million rupiah, or about $150With so much money burning a hole in our pockets, we decided to hit a local flea market. To get there, we took a Grab, which is Indonesia’s answer to Uber. The ride took about ten minutes and cost 43,000 rupiah, or just under $3. Actually, the ride, including taxes and Grab’s platform fee, was only 28,000 rupiah, but Big Daddy Warbucks is a generous tipper.

“You should move to Bali,” our driver told us. “Foreigners love it here because it’s so cheap.”

“But what would we do?” Christina asked.

“Open a nightclub,” he said. “All the nightclubs are owned by foreigners.”

“But there are already a lot of nightclubs,” I said. “It might be a tough market to crack.”

“No, easy,” our driver said, pointing to a rice paddy. “You can buy that land cheap and start a nightclub.”

I doubt we’re going to move to Bali to open a nightclub, but with the way things are going back home you never know. So, for shits and giggles I asked Christina what she’d to call our hypothetical nightclub.

“Sexy Fun Times,” she said.

I thought that was a good name because everyone loves sexy fun times. But if we’re expats on the run from fascism, I want a classic name like Rick’s Café Américain. Of course, Bogart gave up the love of his life for a noble cause in Casablanca, so maybe calling our nightclub Rick’s Café Américain is a bad omen for our relationship. I’ll have to noodle on it—when and if the time comes.

In the meantime, the Seminyak flea market was a lot of fun. After some good-spirited haggling, Christina got herself a “phenomenal deal” on a wicker tote bag. I tried to negotiate a deal on a friendship bracelet, but the man selling it wanted 400,000 rupiah, and I felt weird trying to buy my own friendship.

Eventually, the flea market gave way to a commercial district with a mix of trendy local shops and western brand names. Christina found a few more “great deals,” but for reasons that escape me, you’re only expected to haggle over the price if the proprietor sells their wares from an open-air establishment; inside a brick-and-mortar store, you pay the list price. But all commerce in Bali—from brand names like Polo to mom & pop stalls in the flea market—have one thing in common: Canang sari.

Canang sari: a daily offering made by Balinese Hindus

Canang sari: a daily offering made by Balinese HindusAt one of the shops we stopped at, I asked the proprietor about the offerings.

“It’s to say thank you, to be grateful for all you have,” she explained. “When you start your day, you make an offering, but this offering is old and doesn’t look very good because my day is almost over. The next person will make a new offering.”

The offerings vary, but they’re always housed inside small square baskets.

“This one has flowers, fruit, and candy,” she said.

“And a cigarette,” I added.

“Yes, but these are not like real cigarettes. They’re special for offerings.”

“Special how?”

“They’re cheap,” she said. “You don’t smoke them.”

“But the candy and flowers are real?”

“Oh yes. You offer whatever you have, but candy and flowers are best.”

I don’t know much about Hinduism, but it seemed to me that the Hindu gods have their priorities in order: fake cigarettes, real candy. Maybe when we get home, I’ll take up the practice. Lord knows I’ve got to do something with all our leftover Halloween candy.

Thanks for reading the Situation Bali edition of Situation Normal! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and see what happens when we go to Ubud.