MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 282

May 14, 2014

History Trivia - English physician Edward Jenner gives the first successful smallpox vaccination.

May 14

1264 Barons War: Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, defeated English king Henry III.

1572 Gregory XIII, best known for his calendar reform, was elected pope.

1796 English physician Edward Jenner gave the first successful smallpox vaccination.

1264 Barons War: Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, defeated English king Henry III.

1572 Gregory XIII, best known for his calendar reform, was elected pope.

1796 English physician Edward Jenner gave the first successful smallpox vaccination.

Published on May 14, 2014 06:03

May 13, 2014

History Trivia - Cardinal Richelieu of France created the table knife.

May 13

1497 Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) excommunicated Girolamo Savonarola (Italian Dominican friar and an influential contributor to the politics of Florence. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Rodrigo Borgia).

1515 Mary Tudor, Queen of France and Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk were officially married at Greenwich.

1568 Battle of Langside: the forces of Mary, Queen of Scots, were defeated by a confederacy of Scottish Protestants under James Stewart, Earl of Moray, her half-brother.

1637 Cardinal Richelieu of France created the table knife.

1497 Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) excommunicated Girolamo Savonarola (Italian Dominican friar and an influential contributor to the politics of Florence. He vehemently preached against the moral corruption of much of the clergy at the time, and his main opponent was Rodrigo Borgia).

1515 Mary Tudor, Queen of France and Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk were officially married at Greenwich.

1568 Battle of Langside: the forces of Mary, Queen of Scots, were defeated by a confederacy of Scottish Protestants under James Stewart, Earl of Moray, her half-brother.

1637 Cardinal Richelieu of France created the table knife.

Published on May 13, 2014 05:34

May 12, 2014

The Ancient Greek Riddle That Helps Us Understand Modern Disease Threats (Op-Ed)

By Adam Kucharski, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Finding an Achilles' heelCredit: Γιάννης Ζήσης Even in the face of death, Zeno of Elea knew how to frustrate people. Arrested for plotting against the tyrant Demylus, the ancient Greek philosopher refused to co-operate. The story goes that, rather than talk, he bit off his own tongue and spat it at his captor.

By Adam Kucharski, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Finding an Achilles' heelCredit: Γιάννης Ζήσης Even in the face of death, Zeno of Elea knew how to frustrate people. Arrested for plotting against the tyrant Demylus, the ancient Greek philosopher refused to co-operate. The story goes that, rather than talk, he bit off his own tongue and spat it at his captor.Zeno spent his life exasperating others. Prior to his demise, he had a reputation for creating baffling puzzles. He conjured up a series of apparently contradictory situations known as Zeno’s Paradoxes, which have inspired centuries of debate among philosophers and mathematicians. Now the ideas are helping researchers tackle a far more dangerous problem.

Never-ending race

The most famous of Zeno’s riddles is “Achilles and the tortoise”. Trojan war hero Achilles lines up for a long-distance race against a tortoise (who presumably is still gloating after beating Aesop’s hare). In the interests of fairness, Achilles gives the tortoise a head start – let’s say of one mile. When the race starts, Achilles soon reaches the tortoise’s starting position. However, in the time it takes him to arrive at this point, the tortoise has lumbered forward, perhaps by one tenth of a mile. Achilles quickly covers this ground, but the tortoise has again moved on.

Zeno argued that because the tortoise is always ahead by the time Achilles arrives at its previous position, the hero will never catch up. While the total distance Achilles has to run decreases each time, there are an infinite number of gaps to cover:

1 + 1/10 + 1/100 + 1/1000 + …

And according to Zeno, “It is impossible to traverse an infinite number of things in a finite time.”

It wasn’t until the 19th Century that mathematicians proved Zeno wrong. As the distance between Achilles and the tortoise gets smaller and smaller, Achilles makes up ground faster and faster. In fact, the distance eventually becomes infinitesimally small – so small that Achilles runs it instantly. As a result, he catches up with the tortoise, and overtakes him.

At what point does Achilles reach the tortoise? Thanks to the work of 19th Century mathematicians such as Karl Weierstrass, there is a neat rule for this. For any number n between 0 and 1,

1 + n + n2 + n3 + … = 1/(n-1)

In Zeno’s problem n=1/10, which means that Achilles will catch the tortoise after 1.11 miles or so.

This result might seem like no more than a historical curiosity – a clever solution to an ancient puzzle. But the idea is still very much relevant today. Rather than using it to study a race between a runner and a reptile, mathematicians are now putting it to work in the fight against diseases.

Since Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) was first reported in September 2012, over 400 cases have appeared around the globe. Some outbreaks consist of a single person, infected by an external, but often unknown, source. On other occasions there is a cluster of infected people who had contact with each other.

One way to measure disease transmission is with the reproduction number, denoted R. This is the average number of secondary cases generated by a typical infectious person. If R is greater than one, each infectious person will produce at least one secondary case, and the infection could cause a major epidemic. If R is less than one, the outbreak will eventually fade away.

Even if the infection has so far failed to cause an epidemic, it is still important to know what the reproduction number is. The closer the virus is to that crucial threshold of one, the smaller the hurdle it needs to overcome to spread efficiently.

Using the reproduction number, we can estimate what might happen when a new infection enters a human population. On average, the initial case will generate R secondary cases. These R infections will then generate R more, which means R2 new cases, and so on.

If R is less than one, this will create a pattern just like Achilles and the tortoise. So if we know what the reproduction number is, we can use the same formula to work out how large an outbreak will be on average:

Average size of an outbreak = 1 + R + R2 + R3 + … = 1/(1-R)

The problem is that we don’t know the reproduction number for MERS. Fortunately, we do know how many cases have been reported in each outbreak. Which means to estimate the reproduction number (assuming that it is below 1), we just have to flip the equation around:

R = 1 - 1/(average size)

In the first year of reported MERS cases, disease clusters ranged from a single case to a group of more than 20 people, with an average outbreak size of 2.7 cases. According to the above back-of-the-envelope calculation, the reproduction number could therefore have been around 0.6.

In contrast, there were only two reported clusters of cases in Shanghai during the outbreaks of avian influenza H7N9 in spring 2013. The average outbreak size was therefore 1.1 cases, which gives an estimated reproduction number of 0.1 – much smaller than that for MERS.

Although techniques like these only provide very rough estimates, they give researchers a way to assess disease risk without detailed datasets. Such methods are especially valuable during an outbreak. From avian influenza to MERS, information is at a premium when faced with infections that, much like Zeno, do not give up their secrets easily.

Adam Kucharski does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

http://www.livescience.com/45521-the-ancient-greek-riddle-that-helps-us-understand-modern-disease-threats.html

Published on May 12, 2014 13:15

The Adventures of Cecilia Spark Dragon's Star now available on iTunes

The Adventures of Cecilia Spark Dragon's Star “The creature had been disturbed. Swishing its tail, it sailed effortlessly towards the noise source. It could clearly see something at the edge of the water... The giant water creature was getting closer and closer to its substantial meal. With one final flick of its powerful tail, it would be over.”Cecilia Spark is in a race against time. Her challenge is to save the last Millennium Dragon, captured by a hideous knight of darkness, and reunite him with the star that gives him his power. With Orson, Ractus and Pacha by her side, Cecilia must rescue Fuego and save the Land of Dragons from an endless, desperate gloom. Harassed by crooked imps, captured in the lair of a giant spider, lost in the darkest of dungeons and threatened by a hidden river monster, will Cecilia and her brave friends succeed in their quest?

To listen to an audio sample of Dragon's Star click on the link ...

Audio Book Link from Audible

Audio Book Link from Audiblehttp://www.audible.com/pd/Kids/Dragons-Star-Audiobook/B00K1NBZ1E/ref=a_search_c4_1_

Audio book available from iTunes

Audio book available from iTuneshttps://itunes.apple.com/us/audiobook/dragons-star-adventures-cecilia/id872717713

Published on May 12, 2014 05:18

History Trivia - Richard I of England marries Berengaria of Navarre.

May 12

254 Pope Stephen I succeeded Pope Lucius I as the 23rd pope. He was beheaded while celebrating Mass during Emperor Valerian's persecution of Christians.

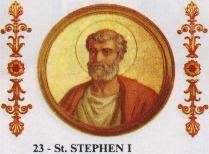

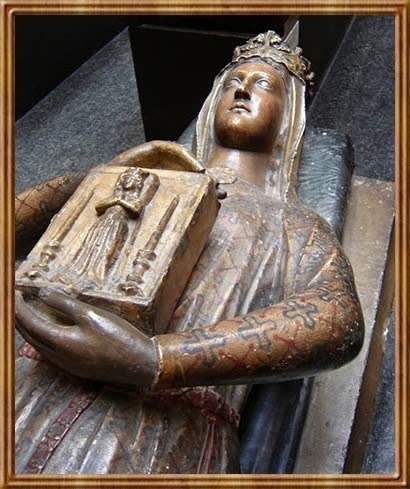

1191 Richard I of England married Berengaria of Navarre.

1215 English barons served an ultimatum on King John.

1264 The Battle of Lewes, between King Henry III of England and the rebel Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, began.

1588 King Henry III fled Paris after Henry of Guise triumphantly entered the city.

1588 King Henry III fled Paris after Henry of Guise triumphantly entered the city.

1641 Thomas Wentworth, chief advisor to Charles I, was beheaded in the Tower of London.

1641 Thomas Wentworth, chief advisor to Charles I, was beheaded in the Tower of London.

254 Pope Stephen I succeeded Pope Lucius I as the 23rd pope. He was beheaded while celebrating Mass during Emperor Valerian's persecution of Christians.

1191 Richard I of England married Berengaria of Navarre.

1215 English barons served an ultimatum on King John.

1264 The Battle of Lewes, between King Henry III of England and the rebel Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, began.

1588 King Henry III fled Paris after Henry of Guise triumphantly entered the city.

1588 King Henry III fled Paris after Henry of Guise triumphantly entered the city. 1641 Thomas Wentworth, chief advisor to Charles I, was beheaded in the Tower of London.

1641 Thomas Wentworth, chief advisor to Charles I, was beheaded in the Tower of London.

Published on May 12, 2014 05:17

May 10, 2014

History Trivia - Religious reformer John Knox ignites the Scottish Reformation

May 11

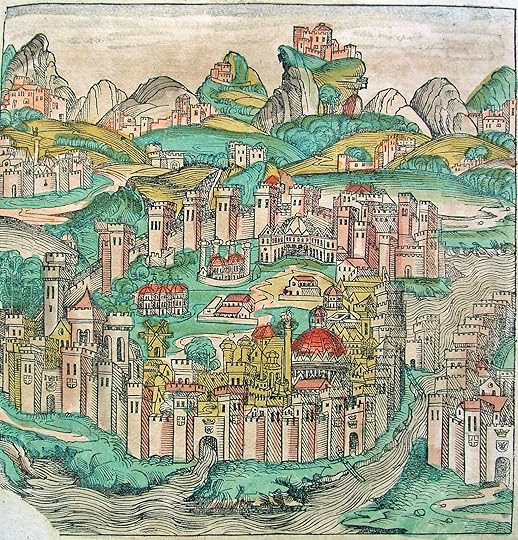

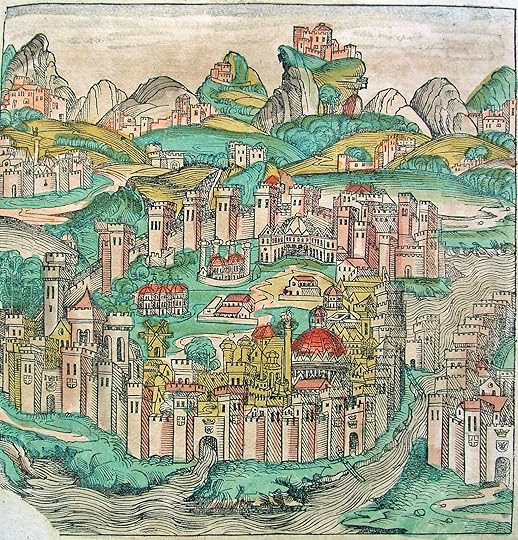

330 Constantinople was dedicated as the new capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great.

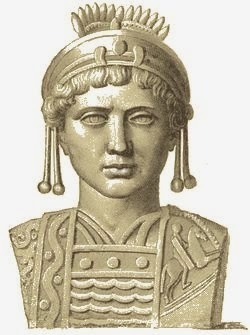

482 Justinian I (the Great) was born. He was Byzantine (East Roman) emperor AD 527-565 who collected Roman laws under one code known as the Justinian Code.

1310 In France fifty-four members of the Knights Templar were burned at the stake as heretics.

1559 Religious reformer John Knox ignited the Scottish Reformation with a sermon at Perth, Scotland.

330 Constantinople was dedicated as the new capital of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine the Great.

482 Justinian I (the Great) was born. He was Byzantine (East Roman) emperor AD 527-565 who collected Roman laws under one code known as the Justinian Code.

1310 In France fifty-four members of the Knights Templar were burned at the stake as heretics.

1559 Religious reformer John Knox ignited the Scottish Reformation with a sermon at Perth, Scotland.

Published on May 10, 2014 17:23

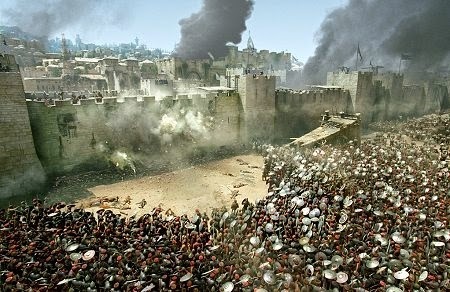

History Trivia - Siege of Jerusalem

May 10

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, opened a full-scale assault on Jerusalem and attacked the city's Third Wall to the northwest.

238 Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus, the Thracian, Roman Emperor, was murdered.

946 Agapetus II elected pope. His pontificate is noted for the spread of Christianity in Denmark.

1291 Scottish nobles recognized the authority of Edward I of England.

70 Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, opened a full-scale assault on Jerusalem and attacked the city's Third Wall to the northwest.

238 Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus, the Thracian, Roman Emperor, was murdered.

946 Agapetus II elected pope. His pontificate is noted for the spread of Christianity in Denmark.

1291 Scottish nobles recognized the authority of Edward I of England.

Published on May 10, 2014 04:14

May 9, 2014

It Got Better: Life Improved After Black Death, Study Finds

By Stephanie Pappas, Senior Writer

This 1977 image shows the necrotic flesh that gave the Black Death its name. This symptom is known as acral gangrene.

This 1977 image shows the necrotic flesh that gave the Black Death its name. This symptom is known as acral gangrene.

Credit: CDC/ William Archibald The Black Death, a plague that first devastated Europe in the 1300s, had a silver lining. After the ravages of the disease, surviving Europeans lived longer, a new study finds.An analysis of bones in London cemeteries from before and after the plague reveals that people had a lower risk of dying at any age after the first plague outbreak compared with before. In the centuries before the Black Death, about 10 percent of people lived past age 70, said study researcher Sharon DeWitte, a biological anthropologist at the University of South Carolina. In the centuries after, more than 20 percent of people lived past that age.

"It is definitely a signal of something very important happening with survivorship," DeWitte told Live Science The plague yearsThe Black Death, caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, first exploded in Europe between 1347 and 1351. The estimated number of deaths ranges from 75 million to 200 million, or between 30 percent and 50 percent of Europe's population. Sufferers developed hugely swollen lymph nodes, fevers and rashes, and vomited blood. The symptom that gave the disease its name was black spots on the skin where the flesh had died.

Scientists long believed that the Black Death killed indiscriminately. But DeWitte's previous research found the plague was like many sicknesses: It preferentially killed the very old and those already in poor health.

That discovery raised the question of whether the plague acted as a "force of selection, by targeting frail people," DeWitte said. If people's susceptibility to the plague was somehow genetic — perhaps they had weaker immune systems, or other health problems with a genetic basis — then those who survived might pass along stronger genes to their children, resulting in a hardier post-plague population.

In fact, research published in February in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that the plague did write itself into human genomes: The descendants of plague-affected populations share certain changes in some immune genes.

Post-plague comeback

To test the idea, DeWitte analyzed bones from London cemeteries housed at the Museum of London's Centre for Human Bioarchaeology. She studied 464 skeletons from three burial grounds dating to the 11th and 12th centuries, before the plague. Another 133 skeletons came from a cemetery used after the Black Death, from the 14th into the 16th century.

These cemeteries provided a mix of people from different socioeconomic classes and ages.

The longevity boost seen after the plague could have come as a result of the plague weeding out the weak and frail, DeWitte said, or it could have been because of another plague side effect. With as much as half of the population dead, survivors in the post-plague era had more resources available to them. Historical documentation records an improvement in diet, especially among the poor, DeWitte said.

"They were eating more meat and fish and better-quality bread, and in greater quantities," she said.

Or the effect could be a combination of both natural selection and improved diet, DeWitte said. She's now starting a project to find out whether Europe's population was particularly unhealthy prior to the Black Death, and if health trends may have given the pestilence a foothold.

The Black Death was an emerging disease in the 14th century, DeWitte said, not unlike HIV or Ebola today. Understanding how human populations responded gives us more knowledge about how disease and humanity interact, she said. Y. pestis strains still cause bubonic plague today, though not at the pandemic levels seen in the Middle Ages.

"Diseases like the Black Death have the ability to powerfully shape human demography and human biology," DeWitte said.

http://www.livescience.com/45428-health-improved-black-death.html

This 1977 image shows the necrotic flesh that gave the Black Death its name. This symptom is known as acral gangrene.

This 1977 image shows the necrotic flesh that gave the Black Death its name. This symptom is known as acral gangrene. Credit: CDC/ William Archibald The Black Death, a plague that first devastated Europe in the 1300s, had a silver lining. After the ravages of the disease, surviving Europeans lived longer, a new study finds.An analysis of bones in London cemeteries from before and after the plague reveals that people had a lower risk of dying at any age after the first plague outbreak compared with before. In the centuries before the Black Death, about 10 percent of people lived past age 70, said study researcher Sharon DeWitte, a biological anthropologist at the University of South Carolina. In the centuries after, more than 20 percent of people lived past that age.

"It is definitely a signal of something very important happening with survivorship," DeWitte told Live Science The plague yearsThe Black Death, caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, first exploded in Europe between 1347 and 1351. The estimated number of deaths ranges from 75 million to 200 million, or between 30 percent and 50 percent of Europe's population. Sufferers developed hugely swollen lymph nodes, fevers and rashes, and vomited blood. The symptom that gave the disease its name was black spots on the skin where the flesh had died.

Scientists long believed that the Black Death killed indiscriminately. But DeWitte's previous research found the plague was like many sicknesses: It preferentially killed the very old and those already in poor health.

That discovery raised the question of whether the plague acted as a "force of selection, by targeting frail people," DeWitte said. If people's susceptibility to the plague was somehow genetic — perhaps they had weaker immune systems, or other health problems with a genetic basis — then those who survived might pass along stronger genes to their children, resulting in a hardier post-plague population.

In fact, research published in February in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggested that the plague did write itself into human genomes: The descendants of plague-affected populations share certain changes in some immune genes.

Post-plague comeback

To test the idea, DeWitte analyzed bones from London cemeteries housed at the Museum of London's Centre for Human Bioarchaeology. She studied 464 skeletons from three burial grounds dating to the 11th and 12th centuries, before the plague. Another 133 skeletons came from a cemetery used after the Black Death, from the 14th into the 16th century.

These cemeteries provided a mix of people from different socioeconomic classes and ages.

The longevity boost seen after the plague could have come as a result of the plague weeding out the weak and frail, DeWitte said, or it could have been because of another plague side effect. With as much as half of the population dead, survivors in the post-plague era had more resources available to them. Historical documentation records an improvement in diet, especially among the poor, DeWitte said.

"They were eating more meat and fish and better-quality bread, and in greater quantities," she said.

Or the effect could be a combination of both natural selection and improved diet, DeWitte said. She's now starting a project to find out whether Europe's population was particularly unhealthy prior to the Black Death, and if health trends may have given the pestilence a foothold.

The Black Death was an emerging disease in the 14th century, DeWitte said, not unlike HIV or Ebola today. Understanding how human populations responded gives us more knowledge about how disease and humanity interact, she said. Y. pestis strains still cause bubonic plague today, though not at the pandemic levels seen in the Middle Ages.

"Diseases like the Black Death have the ability to powerfully shape human demography and human biology," DeWitte said.

http://www.livescience.com/45428-health-improved-black-death.html

Published on May 09, 2014 13:03

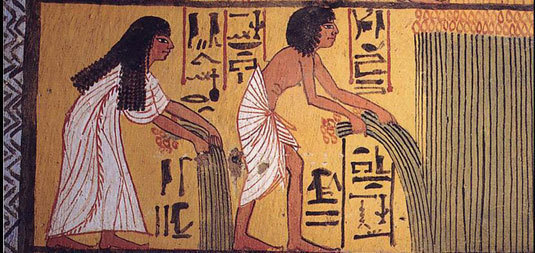

What Did Ancient Egyptians Really Eat?

Alexander Hellemans, ISNS Contributor

(ISNS) -- Did the ancient Egyptians eat like us? If you're a vegetarian, tucking in along the Nile thousands of years ago would have felt just like home.In fact, eating lots of meat is a recent phenomenon. In ancient cultures vegetarianism was much more common, except in nomadic populations. Most sedentary populations ate fruit and vegetables.

(ISNS) -- Did the ancient Egyptians eat like us? If you're a vegetarian, tucking in along the Nile thousands of years ago would have felt just like home.In fact, eating lots of meat is a recent phenomenon. In ancient cultures vegetarianism was much more common, except in nomadic populations. Most sedentary populations ate fruit and vegetables.

Although previous sources found the ancient Egyptians to be pretty much vegetarians, until this new research it wasn't possible to find out the relative amounts of the different foods they ate. Was their daily bread really daily? Did they binge on eggplants and garlic? Why didn't someone spear a fish?

A French research team figured out that by looking at the carbon atoms in mummies that had lived in Egypt between 3500 B.C. and 600 A.D. you could find out what they ate.

All carbon atoms are taken in by plants from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by the process of photosynthesis. By eating plants, and the animals that had eaten plants, the carbon ends up in our bodies.

The sixth-lightest element on the periodic table – carbon – exists in nature as two stable isotopes: carbon-12 and carbon-13. Isotopes of the same element behave the same in chemical reactions but have slightly different atomic masses, with the carbon-13 being slightly heavier than the carbon-12. Plants are categorized into two groups. The first group, C3, is most common in plants such as garlic, eggplants, pears, lentils and wheat. The second smaller group, C4, comprises foodstuffs like millet and sorghum.

The common C3 plants take in less of the heavier isotope carbon-13, while the C4 plants take in more. By measuring the ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12 you can distinguish between these two groups. If you eat a lot of C3 plants, the concentration of carbon-13 isotopes in your body will be lower than if your diet consisted mainly of C4 plants.

The mummies that the French researchers studied were the remains of 45 people that had been shipped to two museums in Lyon, France during the 19th century. "We had an approach that was a little different," explained Alexandra Touzeau, who led the research team at the University of Lyon. "We worked a lot with bones and teeth, while most researchers study hair, collagen and proteins. We also worked on many different periods, with not many individuals for each period, so we could cover a very long time span."

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science . They measured carbon-13 to carbon-12 ratios (and also some other isotope ratios) in bone, enamel and hair in these remains, and compared them to similar measurements performed on pigs that had received controlled diets consisting of different proportions of C3 and C4 foodstuffs. As pigs have a similar metabolism to humans, their carbon isotope ratios could be compared to what was found in the mummies.

Hair absorbs a higher rate of animal proteins than bone or teeth, and the isotope ratios in hair of the mummies corresponded to that found in hair of modern European vegetarians, confirming that the ancient Egyptians were also mainly vegetarians. As is the case with many modern people, their diet was wheat- and barley-based. A main conclusion of the research was that C4 cereals, like millet and sorghum, were only a minor part of the diet, less than 10 percent.

But there were a few surprises.

"We found that the diet was constant over time; we had expected changes," said Touzeau. This showed that the ancient Egyptians adapted well to the environment while the Nile region became increasingly arid between 3500 B.C. and 600 A.D.

To Kate Spence, an archeologist and specialist in ancient Egypt at the U.K.'s University of Cambridge, this could be expected: "Although the area is very arid, they were cultivating crops along the river just by managing irrigation, which is very effective," she said. When the level of the Nile decreased, farmers just came closer to the river and kept on cultivating in the same way.

The real mystery is the fish. Most people would probably expect the ancient Egyptians living along the Nile to have eaten loads of fish. However, despite considerable cultural evidence, there seems to have been little fish in their diet.

"There is abundant evidence for fishing in Egyptian wall reliefs and models (both spear and net fishing), and fish shows up in offering lists. There is also a lot of archeological evidence for fish consumption from sites such as Gaza and Amama," said Spence, who added that some texts indicated that a few fish species were not consumed due to religious associations. "All this makes it a bit surprising that the isotopes should suggest that fish was not widely consumed."

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics. Alexander Hellemans is a freelance science writer who has written for Science, Nature, Scientific American, and many others.

http://www.livescience.com/45450-what-did-ancient-egyptians-really-eat.html

(ISNS) -- Did the ancient Egyptians eat like us? If you're a vegetarian, tucking in along the Nile thousands of years ago would have felt just like home.In fact, eating lots of meat is a recent phenomenon. In ancient cultures vegetarianism was much more common, except in nomadic populations. Most sedentary populations ate fruit and vegetables.

(ISNS) -- Did the ancient Egyptians eat like us? If you're a vegetarian, tucking in along the Nile thousands of years ago would have felt just like home.In fact, eating lots of meat is a recent phenomenon. In ancient cultures vegetarianism was much more common, except in nomadic populations. Most sedentary populations ate fruit and vegetables.Although previous sources found the ancient Egyptians to be pretty much vegetarians, until this new research it wasn't possible to find out the relative amounts of the different foods they ate. Was their daily bread really daily? Did they binge on eggplants and garlic? Why didn't someone spear a fish?

A French research team figured out that by looking at the carbon atoms in mummies that had lived in Egypt between 3500 B.C. and 600 A.D. you could find out what they ate.

All carbon atoms are taken in by plants from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by the process of photosynthesis. By eating plants, and the animals that had eaten plants, the carbon ends up in our bodies.

The sixth-lightest element on the periodic table – carbon – exists in nature as two stable isotopes: carbon-12 and carbon-13. Isotopes of the same element behave the same in chemical reactions but have slightly different atomic masses, with the carbon-13 being slightly heavier than the carbon-12. Plants are categorized into two groups. The first group, C3, is most common in plants such as garlic, eggplants, pears, lentils and wheat. The second smaller group, C4, comprises foodstuffs like millet and sorghum.

The common C3 plants take in less of the heavier isotope carbon-13, while the C4 plants take in more. By measuring the ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12 you can distinguish between these two groups. If you eat a lot of C3 plants, the concentration of carbon-13 isotopes in your body will be lower than if your diet consisted mainly of C4 plants.

The mummies that the French researchers studied were the remains of 45 people that had been shipped to two museums in Lyon, France during the 19th century. "We had an approach that was a little different," explained Alexandra Touzeau, who led the research team at the University of Lyon. "We worked a lot with bones and teeth, while most researchers study hair, collagen and proteins. We also worked on many different periods, with not many individuals for each period, so we could cover a very long time span."

The researchers reported their findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science . They measured carbon-13 to carbon-12 ratios (and also some other isotope ratios) in bone, enamel and hair in these remains, and compared them to similar measurements performed on pigs that had received controlled diets consisting of different proportions of C3 and C4 foodstuffs. As pigs have a similar metabolism to humans, their carbon isotope ratios could be compared to what was found in the mummies.

Hair absorbs a higher rate of animal proteins than bone or teeth, and the isotope ratios in hair of the mummies corresponded to that found in hair of modern European vegetarians, confirming that the ancient Egyptians were also mainly vegetarians. As is the case with many modern people, their diet was wheat- and barley-based. A main conclusion of the research was that C4 cereals, like millet and sorghum, were only a minor part of the diet, less than 10 percent.

But there were a few surprises.

"We found that the diet was constant over time; we had expected changes," said Touzeau. This showed that the ancient Egyptians adapted well to the environment while the Nile region became increasingly arid between 3500 B.C. and 600 A.D.

To Kate Spence, an archeologist and specialist in ancient Egypt at the U.K.'s University of Cambridge, this could be expected: "Although the area is very arid, they were cultivating crops along the river just by managing irrigation, which is very effective," she said. When the level of the Nile decreased, farmers just came closer to the river and kept on cultivating in the same way.

The real mystery is the fish. Most people would probably expect the ancient Egyptians living along the Nile to have eaten loads of fish. However, despite considerable cultural evidence, there seems to have been little fish in their diet.

"There is abundant evidence for fishing in Egyptian wall reliefs and models (both spear and net fishing), and fish shows up in offering lists. There is also a lot of archeological evidence for fish consumption from sites such as Gaza and Amama," said Spence, who added that some texts indicated that a few fish species were not consumed due to religious associations. "All this makes it a bit surprising that the isotopes should suggest that fish was not widely consumed."

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics. Alexander Hellemans is a freelance science writer who has written for Science, Nature, Scientific American, and many others.

http://www.livescience.com/45450-what-did-ancient-egyptians-really-eat.html

Published on May 09, 2014 12:56

Egyptian Mummy Find Sheds Light on Lesser Royals

by Rossella Lorenzi

Dozens of smashed and broken mummies were discovered in a rock-hewn tomb during recent excavations in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Hailed as exceptional, the finding helps answer a key question: Who had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River?

Dozens of smashed and broken mummies were discovered in a rock-hewn tomb during recent excavations in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Hailed as exceptional, the finding helps answer a key question: Who had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River?

Princesses, children, infants and also foreign ladies were among those entombed in the exclusive gateway to the afterlife that once held most of the treasures of Egypt.

The valley became important about 3,500 years ago, when New Kingdom rulers chose it as their final resting place. So far, 65 tombs, built over a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th century B.C., have been unearthed. Often numbered in the order of their discovery, they are labeled from KV1 (built for Ramses VII) to KV65, an unexcavated, possible tomb whose discovery was announced in 2008.

But not all burials were meant for mummy pharaohs.

“Over two-thirds of the tombs in the valley were not prepared for kings, but very little is known about the the identity of those for whom they were made,” Susanne Bickel, professor of Egyptology at the University of Basel, told Discovery News.

Related GalleryWeirdFactsAboutKingTutandHisMummyWho had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River?

Related GalleryWeirdFactsAboutKingTutandHisMummyWho had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River?

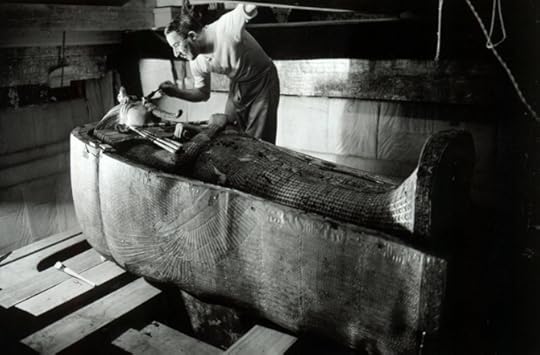

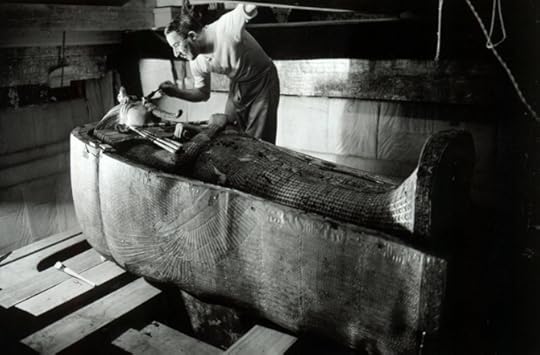

Matjaz Kacicnik, Universität Basel/Ägyptologie View Caption +#1: British archaeologist Howard Carter in the tomb of King Tut Harry Burton/Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#1: British archaeologist Howard Carter in the tomb of King Tut Harry Burton/Wikimedia Commons View Caption +#2: Howard Carter opens the coffin of King Tut. Wikimedia Commons

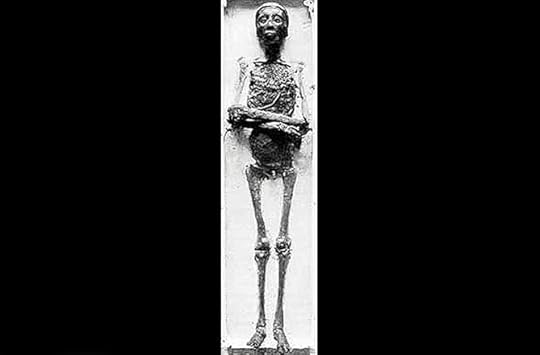

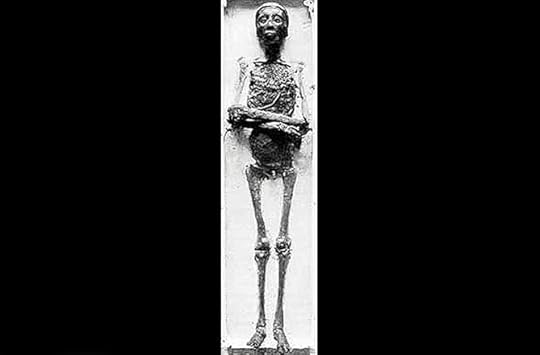

View Caption +#2: Howard Carter opens the coffin of King Tut. Wikimedia Commons View Caption +#3: The mummy of King Tut unwrapped. Wikimedia Commons

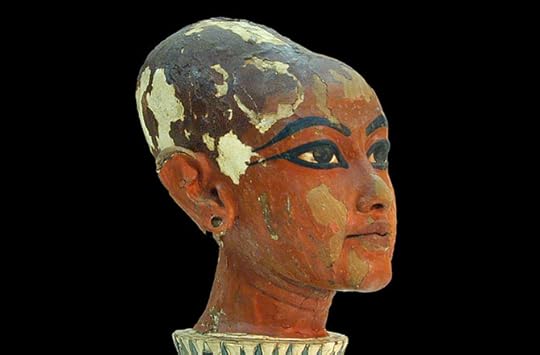

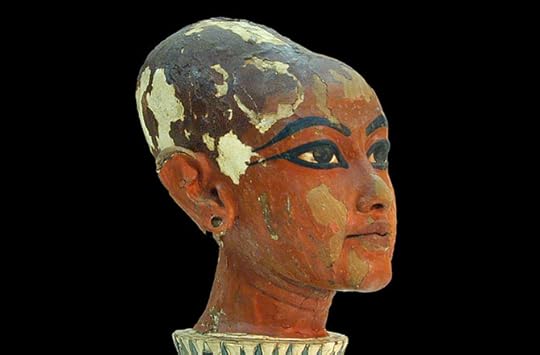

View Caption +#3: The mummy of King Tut unwrapped. Wikimedia Commons View Caption + A head statue of Tutankhamun representing the pharaoh with an elongated skull.

View Caption + A head statue of Tutankhamun representing the pharaoh with an elongated skull.

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra /Wikimedia Commons View Caption +#5: King Tutanhkamun's innermost coffin. Jon Bodsworth /Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#5: King Tutanhkamun's innermost coffin. Jon Bodsworth /Wikimedia Commons View Caption +#6: King Tut's custom-made bandages look like modern gauze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift

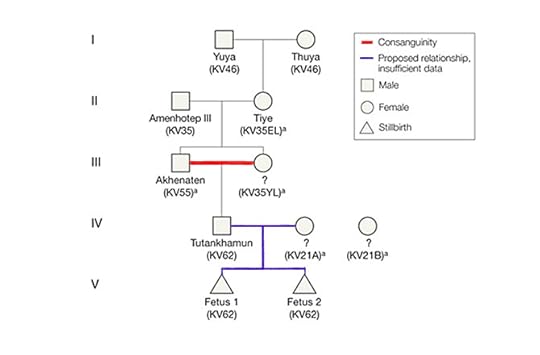

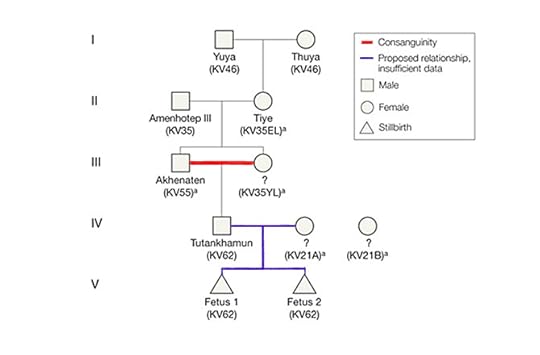

View Caption +#6: King Tut's custom-made bandages look like modern gauze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift View Caption +#7: King Tut's family tree. Zahi Hawass

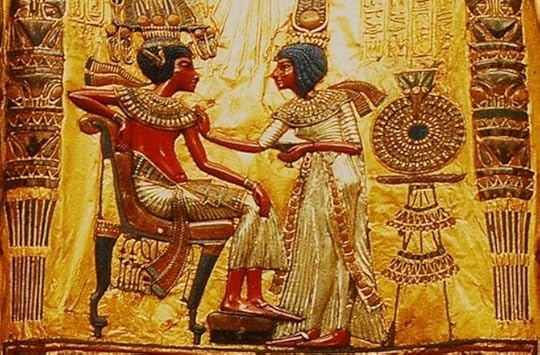

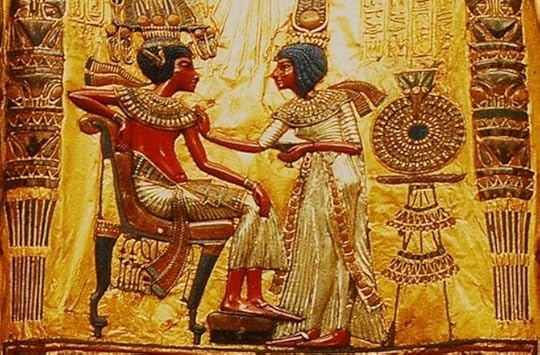

View Caption +#7: King Tut's family tree. Zahi Hawass  View Caption +#8: King Tut and his wife Ankhesenamun H.P.Haack/Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#8: King Tut and his wife Ankhesenamun H.P.Haack/Wikimedia Commons View Caption + The extraterrestrial amulet found in a chest by King Tut's mummy.

View Caption + The extraterrestrial amulet found in a chest by King Tut's mummy.

Roland Unger/Wikimedia Commons Next ickel led a Swiss-Egyptian team at KV 40, a tomb that was first discovered and opened in 1899 by French archaeologist Victor Loret, who did not publish any report about the finding.“Up to now, nothing was known about the layout of the tomb, nor for whom it was built and who was buried there,” Bickel said.

As the archaeologists cleared the 20-foot-deep shaft that provided access to the tomb, they stumbled into five subterranean chambers, filled with fragments of funerary equipment and the mummified remains, mostly decimated by grave robbers, of at least 50 people.

Based on inscriptions on storage jars, Bickel and colleagues were able to identify and name over 30 people related to the families of 18th Dynasty Pharaohs Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III, who are also buried in the Valley of Kings.

The hieratic inscriptions name at least eight hitherto-unknown royal daughters, four princes and several foreign ladies. Most interestingly, carefully mummified children were also found.

“The find does confirm that the Valley of the Kings was used for the burials of members of the immediate entourage of the pharaoh, their large families, to which probably the foreign ladies also belonged,” Bickel said.

http://news.discovery.com/history/archaeology/egyptian-mummy-find-sheds-light-on-lesser-royals-140506.htm

Dozens of smashed and broken mummies were discovered in a rock-hewn tomb during recent excavations in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Hailed as exceptional, the finding helps answer a key question: Who had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River?

Dozens of smashed and broken mummies were discovered in a rock-hewn tomb during recent excavations in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Hailed as exceptional, the finding helps answer a key question: Who had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River?Princesses, children, infants and also foreign ladies were among those entombed in the exclusive gateway to the afterlife that once held most of the treasures of Egypt.

The valley became important about 3,500 years ago, when New Kingdom rulers chose it as their final resting place. So far, 65 tombs, built over a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th century B.C., have been unearthed. Often numbered in the order of their discovery, they are labeled from KV1 (built for Ramses VII) to KV65, an unexcavated, possible tomb whose discovery was announced in 2008.

But not all burials were meant for mummy pharaohs.

“Over two-thirds of the tombs in the valley were not prepared for kings, but very little is known about the the identity of those for whom they were made,” Susanne Bickel, professor of Egyptology at the University of Basel, told Discovery News.

Related GalleryWeirdFactsAboutKingTutandHisMummyWho had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River?

Related GalleryWeirdFactsAboutKingTutandHisMummyWho had the privilege to be buried in the desert valley on the west bank of the Nile River? Matjaz Kacicnik, Universität Basel/Ägyptologie

View Caption +#1: British archaeologist Howard Carter in the tomb of King Tut Harry Burton/Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#1: British archaeologist Howard Carter in the tomb of King Tut Harry Burton/Wikimedia Commons View Caption +#2: Howard Carter opens the coffin of King Tut. Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#2: Howard Carter opens the coffin of King Tut. Wikimedia Commons View Caption +#3: The mummy of King Tut unwrapped. Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#3: The mummy of King Tut unwrapped. Wikimedia Commons View Caption + A head statue of Tutankhamun representing the pharaoh with an elongated skull.

View Caption + A head statue of Tutankhamun representing the pharaoh with an elongated skull. Jean-Pierre Dalbéra /Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#5: King Tutanhkamun's innermost coffin. Jon Bodsworth /Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#5: King Tutanhkamun's innermost coffin. Jon Bodsworth /Wikimedia Commons View Caption +#6: King Tut's custom-made bandages look like modern gauze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift

View Caption +#6: King Tut's custom-made bandages look like modern gauze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift View Caption +#7: King Tut's family tree. Zahi Hawass

View Caption +#7: King Tut's family tree. Zahi Hawass  View Caption +#8: King Tut and his wife Ankhesenamun H.P.Haack/Wikimedia Commons

View Caption +#8: King Tut and his wife Ankhesenamun H.P.Haack/Wikimedia Commons View Caption + The extraterrestrial amulet found in a chest by King Tut's mummy.

View Caption + The extraterrestrial amulet found in a chest by King Tut's mummy.Roland Unger/Wikimedia Commons Next ickel led a Swiss-Egyptian team at KV 40, a tomb that was first discovered and opened in 1899 by French archaeologist Victor Loret, who did not publish any report about the finding.“Up to now, nothing was known about the layout of the tomb, nor for whom it was built and who was buried there,” Bickel said.

As the archaeologists cleared the 20-foot-deep shaft that provided access to the tomb, they stumbled into five subterranean chambers, filled with fragments of funerary equipment and the mummified remains, mostly decimated by grave robbers, of at least 50 people.

Based on inscriptions on storage jars, Bickel and colleagues were able to identify and name over 30 people related to the families of 18th Dynasty Pharaohs Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III, who are also buried in the Valley of Kings.

The hieratic inscriptions name at least eight hitherto-unknown royal daughters, four princes and several foreign ladies. Most interestingly, carefully mummified children were also found.

“The find does confirm that the Valley of the Kings was used for the burials of members of the immediate entourage of the pharaoh, their large families, to which probably the foreign ladies also belonged,” Bickel said.

http://news.discovery.com/history/archaeology/egyptian-mummy-find-sheds-light-on-lesser-royals-140506.htm

Published on May 09, 2014 12:48