MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 276

May 28, 2014

'Extraordinarily Rare' Crusade-Era Seal Discovered in Jerusalem

By Megan Gannon

The seal bears the image of the bearded Saint Sabas (also known as Mar Saba) holding a cross.

The seal bears the image of the bearded Saint Sabas (also known as Mar Saba) holding a cross.

Credit: Israel Antiquities Authority

A rare Crusade-era lead seal used to secure a letter was uncovered in an ancient farmstead in Jerusalem, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced today (May 27).

The 800-year-old seal was likely once fixed to a document delivered to the farm from a sprawling cliffside monastery in the Judean Desert that was founded by Saint Sabas ("Mar Saba" in Aramaic) and once housed hundreds of monks.

"This is an extraordinarily rare find, because no such seal has ever been discovered to date," Benyamin Storchan and Benyamin Dolinka, excavation directors from the Israel Antiquities Authority, said in a statement.

This type of ancient seal was also known as a bulla in Latin. It consisted of two blank lead disks that would have been hammered together with a string between them. Opening the letter would cause obvious damage to the bulla, which was intended to discourage unauthorized people from breaking the seal.

One side of the seal bears the image of the bearded Byzantine-era Saint Sabas, who is wearing a himation (essentially a Greek version of a toga), brandishing a cross in his right hand and perhaps holding a copy of the gospel in his left hand. The other side of the seal is etched with a Greek inscription, translated as: "This is the seal of the Laura of the Holy Sabas." (The monastery was also called the "Great Laura" of Mar Saba. A laura, or lavra, is a type of Orthodox Christian monastery that has a cluster of caves for hermit monks.)

[image error] One side of the seal was impressed with Greek text that read: "This is the seal of the Laura of the Holy Sabas."

[image error] One side of the seal was impressed with Greek text that read: "This is the seal of the Laura of the Holy Sabas."

Credit: Israel Antiquities AuthorityView full size image"The Mar Saba monastery apparently played an important role in the affairs of the Kingdom of Jerusalem during the Crusader period, maintaining a close relationship with the ruling royal family," Robert Kool, a researcher with the Israel Antiquities Authority who examined the seal, said in a statement. "The monastery had numerous properties, and this farm may have been part of the monastery's assets during the Crusader period."

The seal was uncovered during excavations in 2012 in southwestern Jerusalem's Bayit VeGan quarter. The farm site was established during the Byzantine period (5th–6th centuries A.D.) and resettled during the Crusader period (11th–12th centuries A.D.).

A document in the archives of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem refers to a farming settlement known as Thora that was sold to the Mar Saba monastery in 1163–1164. The location of that farm was lost to history, but the Mar Saba seal could link the recently excavated farm to Thora, explained Storchan and Dolinka in a statement.

http://www.livescience.com/45893-rare-lead-seal-discovered-ancient-jerusalem.html

The seal bears the image of the bearded Saint Sabas (also known as Mar Saba) holding a cross.

The seal bears the image of the bearded Saint Sabas (also known as Mar Saba) holding a cross.Credit: Israel Antiquities Authority

A rare Crusade-era lead seal used to secure a letter was uncovered in an ancient farmstead in Jerusalem, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced today (May 27).

The 800-year-old seal was likely once fixed to a document delivered to the farm from a sprawling cliffside monastery in the Judean Desert that was founded by Saint Sabas ("Mar Saba" in Aramaic) and once housed hundreds of monks.

"This is an extraordinarily rare find, because no such seal has ever been discovered to date," Benyamin Storchan and Benyamin Dolinka, excavation directors from the Israel Antiquities Authority, said in a statement.

This type of ancient seal was also known as a bulla in Latin. It consisted of two blank lead disks that would have been hammered together with a string between them. Opening the letter would cause obvious damage to the bulla, which was intended to discourage unauthorized people from breaking the seal.

One side of the seal bears the image of the bearded Byzantine-era Saint Sabas, who is wearing a himation (essentially a Greek version of a toga), brandishing a cross in his right hand and perhaps holding a copy of the gospel in his left hand. The other side of the seal is etched with a Greek inscription, translated as: "This is the seal of the Laura of the Holy Sabas." (The monastery was also called the "Great Laura" of Mar Saba. A laura, or lavra, is a type of Orthodox Christian monastery that has a cluster of caves for hermit monks.)

[image error] One side of the seal was impressed with Greek text that read: "This is the seal of the Laura of the Holy Sabas."

[image error] One side of the seal was impressed with Greek text that read: "This is the seal of the Laura of the Holy Sabas."Credit: Israel Antiquities AuthorityView full size image"The Mar Saba monastery apparently played an important role in the affairs of the Kingdom of Jerusalem during the Crusader period, maintaining a close relationship with the ruling royal family," Robert Kool, a researcher with the Israel Antiquities Authority who examined the seal, said in a statement. "The monastery had numerous properties, and this farm may have been part of the monastery's assets during the Crusader period."

The seal was uncovered during excavations in 2012 in southwestern Jerusalem's Bayit VeGan quarter. The farm site was established during the Byzantine period (5th–6th centuries A.D.) and resettled during the Crusader period (11th–12th centuries A.D.).

A document in the archives of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem refers to a farming settlement known as Thora that was sold to the Mar Saba monastery in 1163–1164. The location of that farm was lost to history, but the Mar Saba seal could link the recently excavated farm to Thora, explained Storchan and Dolinka in a statement.

http://www.livescience.com/45893-rare-lead-seal-discovered-ancient-jerusalem.html

Published on May 28, 2014 14:27

Mystical Paintings Suddenly Appear at Angkor Wat

by Jennifer Viegas

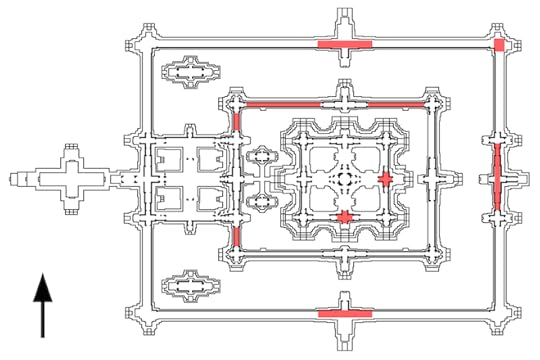

The Locations of the Uncovered Paintings

Over 200 paintings dating to the 16th century were recently discovered at Cambodia’s Temple of Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious monument.

Angkor Wat is already famous for its spectacular bas-relief friezes depicting ceremonial and religious scenes, so this newly uncovered series of images only adds to the temple’s importance. This map of the temple shows, in red, where the newly found paintings are located.

“The paintings found at Angkor Wat seem to belong to a specific phase of the temple’s history in the 16th century A.D. when it was converted from a Vishnavaite Hindu use to Theravada Buddhist,” wrote Noel Hidalgo Tan and colleagues in a paper published in the latest issue of the journal Antiquity. Tan is a researcher in the College of Asia and the Pacific at Australian National University.

“Vishnavaite” refers to the fact that the temple was originally dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. It might have served as a mausoleum when it was first built during the 12th century reign of Suryavarman II (1113–1150 A.D.). “Theravada” refers to the oldest surviving branch of Buddhism.

http://news.discovery.com/history/art-history/mystical-paintings-suddenly-appear-at-angkor-wat-140527.htm

The Locations of the Uncovered Paintings

Over 200 paintings dating to the 16th century were recently discovered at Cambodia’s Temple of Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious monument.

Angkor Wat is already famous for its spectacular bas-relief friezes depicting ceremonial and religious scenes, so this newly uncovered series of images only adds to the temple’s importance. This map of the temple shows, in red, where the newly found paintings are located.

“The paintings found at Angkor Wat seem to belong to a specific phase of the temple’s history in the 16th century A.D. when it was converted from a Vishnavaite Hindu use to Theravada Buddhist,” wrote Noel Hidalgo Tan and colleagues in a paper published in the latest issue of the journal Antiquity. Tan is a researcher in the College of Asia and the Pacific at Australian National University.

“Vishnavaite” refers to the fact that the temple was originally dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. It might have served as a mausoleum when it was first built during the 12th century reign of Suryavarman II (1113–1150 A.D.). “Theravada” refers to the oldest surviving branch of Buddhism.

http://news.discovery.com/history/art-history/mystical-paintings-suddenly-appear-at-angkor-wat-140527.htm

Published on May 28, 2014 14:20

Earliest Evidence of Flower Pollination by Birds Unearthed

By Joseph Castro,

A 47-million-year-old skeleton of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus, which likely pollinated flowers when alive.

A 47-million-year-old skeleton of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus, which likely pollinated flowers when alive.

Credit: © Senckenberg

Birds have been visiting and pollinating flowers for at least 47 million years, fossil evidence now suggests. The new find pushes back the onset of ornithophily, or bird pollination, by about 17 million years, researchers say.

To pollinate, most species of angiosperms (flowering plants) require assistance from animals, particularly insects and birds. Though research suggests that insects have been pollinating flowers since the early Cretaceous period, over 100 million years ago, the onset of ornithophily has long remained elusive. Previously, fossils of modern-type hummingbirds suggested ornithophily began as early as 30 million years ago, but this conclusion was only inferred indirectly from the birds' long beaks and presumed hovering capabilities.

However, researchers have now analyzed a well-preserved, 47-million-year-old fossil of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus, and found that the animal's stomach contents contain numerous angiosperm pollen grains. The discovery is the first direct fossil evidence of flower visitation by birds, and suggests that ornithophily is far older than previously believed. [See Beautiful Images of the World's Hummingbirds]

"We don't just have a fossil that can tell us about the birds. We have a unique sign that tells us about the special ecosystem it lived in," said study lead author Gerald Mayr, an ornithologist at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt, Germany. "There's a bigger story that this single skeleton can tell."

[image error] A 47-million-year-old fossil of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus had pollen grains from flowering plants in its stomach, researchers found.

A 47-million-year-old fossil of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus had pollen grains from flowering plants in its stomach, researchers found.

Credit: Gerald Mayr and Volker Wilde

View full size imageScientists from the institute originally found the skeleton in 2012 in Germany's Messel Pit, an oil shale pit known for its rich fossil collection, which includes mating turtlesand very early primates. The new fossil is one of just three specimens of P. tessellatus, an extinct bird whose family tree is unresolved (experts believe the birds may be related to cuckoos or parrots).

The fossil is a complete skeleton with a lot of preserved soft tissues, including plumage and claw sheaths. In the bird's stomach, Mayr and his colleague, paleobotanist Volker Wilde, discovered hundreds of pollen grains of different sizes, some of which were clumped together. The pollen doesn't appear to match any fossil or extant pollen the researchers are familiar with. "We're not sure what exactly it is," Mayr told Live Science, adding that the pollen species hasn't been found in the Messel Pit before.

The bird's stomach also contained unidentifiable insect remains. Though insects also ingest pollen grains, the researchers believe there are not enough insect remains in the bird's stomach for the pollen to have come from the insects' intestinal tracts. What's more, the large size of some of the grains and their clumping suggest that the bird directly ingested the pollen from flowers, likely while hunting for nectar.

The scientists also analyzed the morphology, or physical characteristics, of the fossilized P. tessellatus. The bird had a long, slender beak with elongated nasal openings, an adaptation that increases the flexibility of the beak tip — this feature is also seen in hummingbirds, which feed off the nectar located deep in flowers. It also had a fourth toe that could be turned backward, a morphology that may have allowed the bird to clasp or climb branches, helping it visit flowers.

The results suggest that flowering plants able to take advantage of bird pollination likely existed before 47 million years ago, Mayr said. What's more, because the fossil predates any extant nectarivorous bird groups, or those that feed on a flower's nectar, the find suggests that plants likely evolved the morphology for ornithophily before modern nectarivorous birds evolved.

"When you read about the flower-bird interaction, you always read that the bird-pollinated plants coevolved with modern birds," Mayr said. "But it's actually much more complex than that."

http://www.livescience.com/45901-earliest-flower-pollination-by-birds.html

A 47-million-year-old skeleton of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus, which likely pollinated flowers when alive.

A 47-million-year-old skeleton of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus, which likely pollinated flowers when alive.Credit: © Senckenberg

Birds have been visiting and pollinating flowers for at least 47 million years, fossil evidence now suggests. The new find pushes back the onset of ornithophily, or bird pollination, by about 17 million years, researchers say.

To pollinate, most species of angiosperms (flowering plants) require assistance from animals, particularly insects and birds. Though research suggests that insects have been pollinating flowers since the early Cretaceous period, over 100 million years ago, the onset of ornithophily has long remained elusive. Previously, fossils of modern-type hummingbirds suggested ornithophily began as early as 30 million years ago, but this conclusion was only inferred indirectly from the birds' long beaks and presumed hovering capabilities.

However, researchers have now analyzed a well-preserved, 47-million-year-old fossil of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus, and found that the animal's stomach contents contain numerous angiosperm pollen grains. The discovery is the first direct fossil evidence of flower visitation by birds, and suggests that ornithophily is far older than previously believed. [See Beautiful Images of the World's Hummingbirds]

"We don't just have a fossil that can tell us about the birds. We have a unique sign that tells us about the special ecosystem it lived in," said study lead author Gerald Mayr, an ornithologist at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Frankfurt, Germany. "There's a bigger story that this single skeleton can tell."

[image error]

A 47-million-year-old fossil of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus had pollen grains from flowering plants in its stomach, researchers found.

A 47-million-year-old fossil of the extinct bird Pumiliornis tessellatus had pollen grains from flowering plants in its stomach, researchers found.Credit: Gerald Mayr and Volker Wilde

View full size imageScientists from the institute originally found the skeleton in 2012 in Germany's Messel Pit, an oil shale pit known for its rich fossil collection, which includes mating turtlesand very early primates. The new fossil is one of just three specimens of P. tessellatus, an extinct bird whose family tree is unresolved (experts believe the birds may be related to cuckoos or parrots).

The fossil is a complete skeleton with a lot of preserved soft tissues, including plumage and claw sheaths. In the bird's stomach, Mayr and his colleague, paleobotanist Volker Wilde, discovered hundreds of pollen grains of different sizes, some of which were clumped together. The pollen doesn't appear to match any fossil or extant pollen the researchers are familiar with. "We're not sure what exactly it is," Mayr told Live Science, adding that the pollen species hasn't been found in the Messel Pit before.

The bird's stomach also contained unidentifiable insect remains. Though insects also ingest pollen grains, the researchers believe there are not enough insect remains in the bird's stomach for the pollen to have come from the insects' intestinal tracts. What's more, the large size of some of the grains and their clumping suggest that the bird directly ingested the pollen from flowers, likely while hunting for nectar.

The scientists also analyzed the morphology, or physical characteristics, of the fossilized P. tessellatus. The bird had a long, slender beak with elongated nasal openings, an adaptation that increases the flexibility of the beak tip — this feature is also seen in hummingbirds, which feed off the nectar located deep in flowers. It also had a fourth toe that could be turned backward, a morphology that may have allowed the bird to clasp or climb branches, helping it visit flowers.

The results suggest that flowering plants able to take advantage of bird pollination likely existed before 47 million years ago, Mayr said. What's more, because the fossil predates any extant nectarivorous bird groups, or those that feed on a flower's nectar, the find suggests that plants likely evolved the morphology for ornithophily before modern nectarivorous birds evolved.

"When you read about the flower-bird interaction, you always read that the bird-pollinated plants coevolved with modern birds," Mayr said. "But it's actually much more complex than that."

http://www.livescience.com/45901-earliest-flower-pollination-by-birds.html

Published on May 28, 2014 14:10

King Richard III will be reburied in Leicester, High Court rules

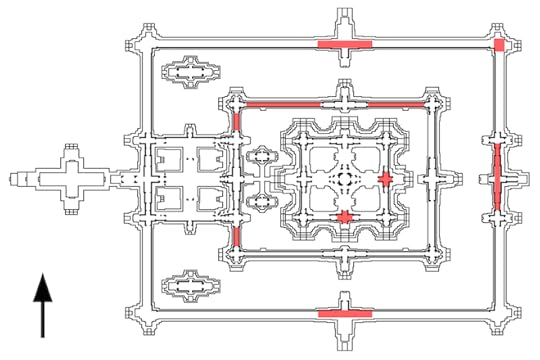

By Stephanie PappasFeb. 4 2013: The curved spine and other long lost remains of England's King Richard III, missing for 500 years. Richard was immortalized in a play by Shakespeare as a hunchbacked usurper who left a trail of bodies including those of his two young nephews, murdered in the Tower of London on his way to the throne.AP Photo/ University of LeicesterA judicial review concerning the final resting place of King Richard III has determined that the University of Leicester has the right to reinter the King's remains at Leicester Cathedral in England.

By Stephanie PappasFeb. 4 2013: The curved spine and other long lost remains of England's King Richard III, missing for 500 years. Richard was immortalized in a play by Shakespeare as a hunchbacked usurper who left a trail of bodies including those of his two young nephews, murdered in the Tower of London on his way to the throne.AP Photo/ University of LeicesterA judicial review concerning the final resting place of King Richard III has determined that the University of Leicester has the right to reinter the King's remains at Leicester Cathedral in England.Richard III, who ruled England from 1483 to 1485, died at the Battle of Bosworth Field and was buried in a hasty grave in Leicester. The exact location was lost to history until 2012, when archaeologists on the hunt for the king's bones excavated a parking lot and found the skeleton, its spine bent with scoliosis and skull marred by battle wounds.

ADVERTISEMENTADVERTISEMENTThe decision, released May 23, is a response to a legal challenge by the Plantagenet Alliance, a group of indirect descendants and supporters who want a say in where King Richard III is reburied. The University of Leicester holds the excavation license for the King's grave, giving it the authority to reinter the bones under standard archaeological practice. [See Photos of the Search of King Richard III]

"I am absolutely delighted that the High Court has ruled that our exhumation license is valid," archaeologist Richard Buckley, who led the dig that made the discovery, said in a statement. "We may now make arrangements for the transfer of Richard III's remains from the University of Leicester to Leicester Cathedral where they may be reinterred with dignity and honor as befitting the last Plantagenet King of England."

The Ministry of Justice Secretary Chris Grayling echoed that delight in a statement today, though said he is "frustrated and angry that the Plantagenet Alliance a group with tenuous claims to being relatives of Richard III have taken up so much time and public money."

The Alliance, on their Facebook page today, responded to the decision: "

We are naturally disappointed at the decision reached, but we are grateful to have had the opportunity to raise this nationally significant matter before the courts."

Rightful grave?

The University's plan has long been to rebury Richard's bones in the Leicester Cathedral, and has released plans showing a spare raise tomb surrounded by stained-glass windows.

But the Plantagenet Alliance and others disapproved. Many said they would like to see the King reburied in York, a town where he spent much of his life.

"We believe that such an interment was the desire of King Richard in life," the Alliance wrote in a statement explaining their "King Richard III Campaign."

Richard III's posthumous fate raises passions, because the man himself has a bit of a cult following. Richard III enthusiasts, or Ricardians, are fascinated by the King and his reign and are often adamant about reclaiming him from the Shakespearian portrayal as a heartless, wicked villain.

"When you read about what Richard did with his parliament and how he behaved in military matters, you find quite an extraordinary character," Wendy Moorhen, the deputy chair of the Richard III Society, told Live Science last year.

Controversial king

Today's High Court decision comes after much debate.

Hearings regarding the University's reburial rights began in March. Advocates for not burying the King in Leicester requested a public consultation with views from the royal family, churches and those who claim to be the king's relatives. Richard III left no direct descendants, though DNA from his bones matched DNA from living descendants along his maternal line.

The King's genetic material is another source of controversy. The University of Leicester has announced plans to fully sequence Richard III's genome, which has some historians balking.

"Her Majesty the Queen would not allow exhumation of other royal remains, or the testing of them," John Ashdown-Hill, an independent historian involved with the search for the bones, told Live Science in February.

http://www.foxnews.com/science/2014/05/27/king-richard-iii-will-be-reburied-in-leicester-high-court-rules/

Published on May 28, 2014 14:05

2,300-year-old false tooth removed in northern France

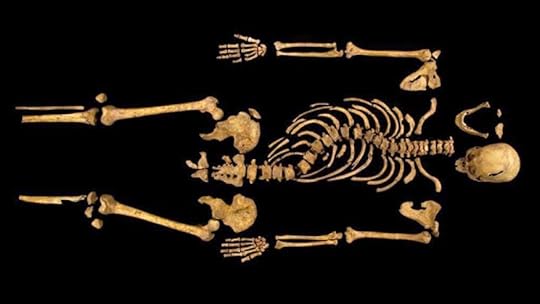

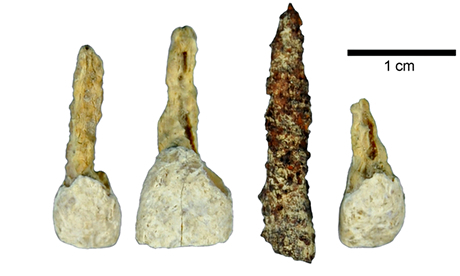

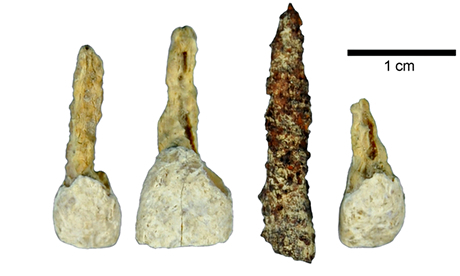

Iron implant is same size and shape as incisors found with Celtic woman's remains – and was likely added after death Maev Kennedy  An iron false tooth found with real teeth at a Celtic grave at Le Chene, France. The implant is the oldest of its kind so far discovered in western Europe. Photograph: Antiquity Publications LtdAn iron tooth implant fitted about 2,300 years ago has been found in the grave of a young woman in northern France. Archaeologists believe it may have been fitted to beautify her corpse, as it would have been too excruciating to have had it hammered into the living jaw.

An iron false tooth found with real teeth at a Celtic grave at Le Chene, France. The implant is the oldest of its kind so far discovered in western Europe. Photograph: Antiquity Publications LtdAn iron tooth implant fitted about 2,300 years ago has been found in the grave of a young woman in northern France. Archaeologists believe it may have been fitted to beautify her corpse, as it would have been too excruciating to have had it hammered into the living jaw.

The corroded piece of metal is the same size and shape as the other incisors from her upper jaw – which did not survive as the timber tomb collapsed and crushed her skull – and its appearance may originally have been improved by a wooden or ivory covering.

The implant, the oldest of its kind discovered in western Europe, is 400 years older than one from another grave in France, found in the 1990s at Essonne. That unfortunate young man had lost all his top left molars, so the iron implant was probably to help him chew.

The new find replaced the only tooth lost by the woman, which would have caused her no practical problems but would have been very visible.

The French archaeologists, who report their discovery in the June edition of the Antiquity journal, say the discovery was totally unexpected.

Although the Celts were renowned for their craftsmanship in metal and timber, the team says little is known about their medical knowledge before the Romans overran their territories.

The woman was buried in a richly furnished timber chamber, originally surrounded by a wooden fence, near the graves of three other women, at Le Chene, south-east of Paris.

Buried with her were bronze torcs, anklets and bracelets, brooches and belt ornaments, coral and amber necklaces, and an iron currency bar, all in an elaborately constructed burial chamber and enclosure – all signs of wealth "of a refined and ostentatious elite".

The items were found among a small heap of crushed bones, all that survived of the skeleton apart from the perfectly preserved teeth – and the iron implant.

False or replacement teeth have been discovered in skulls from ancient Egypt, including a 5,500-year-old one made of shell, intended to make the body as complete as possible for the afterlife. False teeth made of bone, or recycled animal teeth, were used by elite Etruscan women in Italy, where the Celts had trading connections and may have got the idea.

The archaeologists made some gruesome calculations about how far the spike would have been hammered into the pulp canal of nerves and blood vessels to anchor it soundly.

She may already have been dead when it was done, to improve the appearance of her corpse for the funeral service. If she was still alive it would have been an agonising process, and could have resulted in a fatal infection. "Iron is not biocompatible and the absence of sterile conditions would have provoked an unfavourable host response," said the team of archaeologists.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/28/2300-year-old-false-tooth-france-iron-implant

An iron false tooth found with real teeth at a Celtic grave at Le Chene, France. The implant is the oldest of its kind so far discovered in western Europe. Photograph: Antiquity Publications LtdAn iron tooth implant fitted about 2,300 years ago has been found in the grave of a young woman in northern France. Archaeologists believe it may have been fitted to beautify her corpse, as it would have been too excruciating to have had it hammered into the living jaw.

An iron false tooth found with real teeth at a Celtic grave at Le Chene, France. The implant is the oldest of its kind so far discovered in western Europe. Photograph: Antiquity Publications LtdAn iron tooth implant fitted about 2,300 years ago has been found in the grave of a young woman in northern France. Archaeologists believe it may have been fitted to beautify her corpse, as it would have been too excruciating to have had it hammered into the living jaw.The corroded piece of metal is the same size and shape as the other incisors from her upper jaw – which did not survive as the timber tomb collapsed and crushed her skull – and its appearance may originally have been improved by a wooden or ivory covering.

The implant, the oldest of its kind discovered in western Europe, is 400 years older than one from another grave in France, found in the 1990s at Essonne. That unfortunate young man had lost all his top left molars, so the iron implant was probably to help him chew.

The new find replaced the only tooth lost by the woman, which would have caused her no practical problems but would have been very visible.

The French archaeologists, who report their discovery in the June edition of the Antiquity journal, say the discovery was totally unexpected.

Although the Celts were renowned for their craftsmanship in metal and timber, the team says little is known about their medical knowledge before the Romans overran their territories.

The woman was buried in a richly furnished timber chamber, originally surrounded by a wooden fence, near the graves of three other women, at Le Chene, south-east of Paris.

Buried with her were bronze torcs, anklets and bracelets, brooches and belt ornaments, coral and amber necklaces, and an iron currency bar, all in an elaborately constructed burial chamber and enclosure – all signs of wealth "of a refined and ostentatious elite".

The items were found among a small heap of crushed bones, all that survived of the skeleton apart from the perfectly preserved teeth – and the iron implant.

False or replacement teeth have been discovered in skulls from ancient Egypt, including a 5,500-year-old one made of shell, intended to make the body as complete as possible for the afterlife. False teeth made of bone, or recycled animal teeth, were used by elite Etruscan women in Italy, where the Celts had trading connections and may have got the idea.

The archaeologists made some gruesome calculations about how far the spike would have been hammered into the pulp canal of nerves and blood vessels to anchor it soundly.

She may already have been dead when it was done, to improve the appearance of her corpse for the funeral service. If she was still alive it would have been an agonising process, and could have resulted in a fatal infection. "Iron is not biocompatible and the absence of sterile conditions would have provoked an unfavourable host response," said the team of archaeologists.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/28/2300-year-old-false-tooth-france-iron-implant

Published on May 28, 2014 13:58

Blog Tour - My Writing Process

Many thanks to author and blogger, Celia Kennedy, who asked me to join in the blog tag tour. Please make sure to check out Celia's answers on her blog . http://womanreinventsself.blogspot.com/

Kindly visit her site and learn more about her books, Charlotte's Restrained and Venus Rising

Now to the good stuff - answering the questions:

What am I working on?

Currently, I am producing audio editions of my published works. The Briton and the Dane and The Briton and the Dane: Timeline are in production and should be available on Audible and iTunes by mid-July. The audio version of the remaining titles in the franchise will be available in the near future.

How does my writing process work?

Once I've completed the story, I set it aside for a week before reading it again, but wearing my editor's cap. I then submit the manuscript to my editor for a final review. Next step is Whispering Legends Press publishing the work.

How does my work differ from others of its genre?

I delve into the mindset of the characters, presenting two sides of the coin, creating a gray area, which might have the reader becoming sympathetic to the villain's plight. There are many conflicting emotions throughout my novels pertaining to religion, paternal approval and the effect deployment has on military families.

Why do I write what I do?

After reading Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe, I became enthralled with early British history, and admit to being an incurable romantic Anglophile, and less nobly, and much more irritatingly, a Romanphile, according to some Brit friends.

Who's up next? That would be author K. Meador, noted for not only her novels set during America's Civil War, but also for her children's stories, notably, On Top of the Rainbow and Princess Alexia and the Dragon Don't forget to swing by her blog http://inthemidst-km.blogspot.com/

Published on May 28, 2014 04:27

History Trivia - The Spanish Armada sets sail from Lisbon, heading for the English Channel.

May 28,

585 BC A solar eclipse occurred, as predicted by Greek philosopher and scientist Thales, while Alyattes was battling Cyaxares in the Battle of the Eclipse, leading to a truce. This was one of the cardinal dates from which other dates can be calculated.

1291 Acre, in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, fell to the Moslems, ending the Crusades.

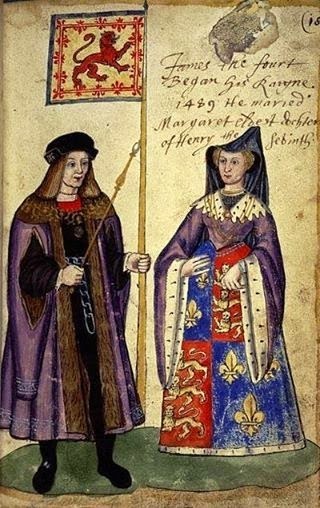

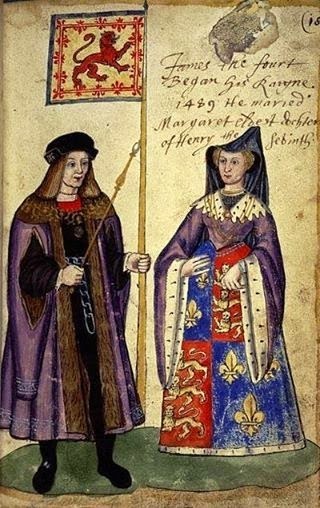

1503 James IV of Scotland and Margaret Tudor were married according to a Papal Bull by Pope Alexander VI. A Treaty of Everlasting Peace between Scotland and England signed on that occasion resulted in a peace that lasted ten years.

1588 The Spanish Armada, with 130 ships and 30,000 men, set sail from Lisbon heading for the English Channel. (It would take until May 30 for all ships to leave port).

585 BC A solar eclipse occurred, as predicted by Greek philosopher and scientist Thales, while Alyattes was battling Cyaxares in the Battle of the Eclipse, leading to a truce. This was one of the cardinal dates from which other dates can be calculated.

1291 Acre, in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, fell to the Moslems, ending the Crusades.

1503 James IV of Scotland and Margaret Tudor were married according to a Papal Bull by Pope Alexander VI. A Treaty of Everlasting Peace between Scotland and England signed on that occasion resulted in a peace that lasted ten years.

1588 The Spanish Armada, with 130 ships and 30,000 men, set sail from Lisbon heading for the English Channel. (It would take until May 30 for all ships to leave port).

Published on May 28, 2014 04:22

May 27, 2014

Battered pot found in Cornish garage unlocks Egypt excavation secrets

Pot sheds light on the work of archeologist Flinders Petrie whose finds scattered across the world in the late 19th century

Maev Kennedy

Little ancient Egyptian pot found in a garage in Cornwall, being conserved by the Petrie for display with other objects excavated from the same grave. Photograph: Christian Sinibaldi for the Guardian

Little ancient Egyptian pot found in a garage in Cornwall, being conserved by the Petrie for display with other objects excavated from the same grave. Photograph: Christian Sinibaldi for the Guardian

A battered pot found in a garage in Cornwall, broken in antiquity and broken again and mended with superglue some 5,500 years later, was treasure – but the scruffy little cardboard label it held is now unlocking a lost history of finds from excavations in Egypt scattered across the world in the late 19th century.

The pot came with an odd family legend that back in the 1950s it was accepted in lieu of a fare by a taxi driver in High Wycombe. Alice Stevenson, curator at the Petrie Museum in London, which among its 80,000 objects has the original excavation records and hundreds of pieces from the same Egyptian cemetery, believes the story is true and may even have identified the mysterious passenger.

"I got the email from them on my second week in this job," Stevenson said. "I could hardly believe what they'd found. I literally jumped up and down in excitement. The pot is wonderful, a rare find indeed. The label is absolutely fantastic."

When Guy Funnell and Amanda Hawkins found the pot while clearing a garage stacked with his father's possessions, they made the connection with a BBC documentary they had recently seen, The Man Who Discovered Egypt, about the archaeologist Flinders Petrie.

Petrie's meticulous records and scientifically based excavations in the region transformed archaeology, and he created a timeline still in use today through sorting thousands of pots by date, enabling tombs, temples and entire towns to be dated from the fragments of broken pottery on the sites.

The little black and red pot was one of the few occasions when he was not only completely wrong, but admitted that, mortifyingly, a French rival was right.

Petrie, like his 19th-century contemporaries, sent back tons of material from Egypt to universities and museums funding his excavations, and later sold a huge collection that became the basis of the Petrie Museum – the most difficult to find in London, "temporarily" housed in an old stables on the UCL Bloomsbury campus alleyway since the 1950s, but with the finest collection of material from the region outside Egypt.

It was known that he gave pieces to individuals, at a time when a visit to a celebrity archaeologist's dig was the highlight of any tourist or VIP trip down the Nile. The little label proves this was done on a systematic basis not previously guessed at. It is a neat commercially printed card, with an Egyptianate border, boasting that the "Libyan Pottery" from 3,000 BC was discovered by Prof WM Flinders Petrie in 1894-5. The card was clearly one of many, but pot, card, and excavation record are linked by the faintly pencilled number 1754.

"There were obviously many such cards, but I have never seen or heard of one before – there must be more out there, which would help us trace the distribution of this material through museums and private collections," Stevenson said.

The pot is now being conserved for display at the museum, on loan for a year. Funnell dimly remembers it in childhood, and his mother remembered the story that his grandfather, Charles Funnell, was given it to settle not just one but several unpaid taxi fares.

Stevenson believes the mystery customer may have been a curator at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, Joseph Grafton Milne, who died in 1951, but was recorded as visiting Petrie in Egypt in the 1890s. The link between the distinctive pots: the Ashmolean has a bowl from Milne's collection from the same grave as Funnell's pot, and she thinks it is probable Milne obtained both from Petrie.

The Petrie has some tiny shells, pierced as beads, and a piece of rock crystal from the same grave, but the records show many more pots came from the same grave, and thousands from the cemetery, and the card may help to trace them.

Petrie was wrong about the pots: they were Egyptian, not Libyan. He was fooled because their distinctive black fire-scorched rims were so different from the others he found. However, a French scholar, Jacques de Morgan, established that they were Egyptian but pre-Dynastic, 600 years older than Petrie first believed.

"It was one of the few occasions when Petrie was not only wrong, but admitted it publicly," Stevenson said, "a very unusual occurrence."

After conservation work, the treasure from the Cornish garage will go on display next month, a scruffy star of the museum's Festival of Pots.

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/may/26/pot-found-cornwall-garage-reveals-egypt-excavation-history

Maev Kennedy

Little ancient Egyptian pot found in a garage in Cornwall, being conserved by the Petrie for display with other objects excavated from the same grave. Photograph: Christian Sinibaldi for the Guardian

Little ancient Egyptian pot found in a garage in Cornwall, being conserved by the Petrie for display with other objects excavated from the same grave. Photograph: Christian Sinibaldi for the GuardianA battered pot found in a garage in Cornwall, broken in antiquity and broken again and mended with superglue some 5,500 years later, was treasure – but the scruffy little cardboard label it held is now unlocking a lost history of finds from excavations in Egypt scattered across the world in the late 19th century.

The pot came with an odd family legend that back in the 1950s it was accepted in lieu of a fare by a taxi driver in High Wycombe. Alice Stevenson, curator at the Petrie Museum in London, which among its 80,000 objects has the original excavation records and hundreds of pieces from the same Egyptian cemetery, believes the story is true and may even have identified the mysterious passenger.

"I got the email from them on my second week in this job," Stevenson said. "I could hardly believe what they'd found. I literally jumped up and down in excitement. The pot is wonderful, a rare find indeed. The label is absolutely fantastic."

When Guy Funnell and Amanda Hawkins found the pot while clearing a garage stacked with his father's possessions, they made the connection with a BBC documentary they had recently seen, The Man Who Discovered Egypt, about the archaeologist Flinders Petrie.

Petrie's meticulous records and scientifically based excavations in the region transformed archaeology, and he created a timeline still in use today through sorting thousands of pots by date, enabling tombs, temples and entire towns to be dated from the fragments of broken pottery on the sites.

The little black and red pot was one of the few occasions when he was not only completely wrong, but admitted that, mortifyingly, a French rival was right.

Petrie, like his 19th-century contemporaries, sent back tons of material from Egypt to universities and museums funding his excavations, and later sold a huge collection that became the basis of the Petrie Museum – the most difficult to find in London, "temporarily" housed in an old stables on the UCL Bloomsbury campus alleyway since the 1950s, but with the finest collection of material from the region outside Egypt.

It was known that he gave pieces to individuals, at a time when a visit to a celebrity archaeologist's dig was the highlight of any tourist or VIP trip down the Nile. The little label proves this was done on a systematic basis not previously guessed at. It is a neat commercially printed card, with an Egyptianate border, boasting that the "Libyan Pottery" from 3,000 BC was discovered by Prof WM Flinders Petrie in 1894-5. The card was clearly one of many, but pot, card, and excavation record are linked by the faintly pencilled number 1754.

"There were obviously many such cards, but I have never seen or heard of one before – there must be more out there, which would help us trace the distribution of this material through museums and private collections," Stevenson said.

The pot is now being conserved for display at the museum, on loan for a year. Funnell dimly remembers it in childhood, and his mother remembered the story that his grandfather, Charles Funnell, was given it to settle not just one but several unpaid taxi fares.

Stevenson believes the mystery customer may have been a curator at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, Joseph Grafton Milne, who died in 1951, but was recorded as visiting Petrie in Egypt in the 1890s. The link between the distinctive pots: the Ashmolean has a bowl from Milne's collection from the same grave as Funnell's pot, and she thinks it is probable Milne obtained both from Petrie.

The Petrie has some tiny shells, pierced as beads, and a piece of rock crystal from the same grave, but the records show many more pots came from the same grave, and thousands from the cemetery, and the card may help to trace them.

Petrie was wrong about the pots: they were Egyptian, not Libyan. He was fooled because their distinctive black fire-scorched rims were so different from the others he found. However, a French scholar, Jacques de Morgan, established that they were Egyptian but pre-Dynastic, 600 years older than Petrie first believed.

"It was one of the few occasions when Petrie was not only wrong, but admitted it publicly," Stevenson said, "a very unusual occurrence."

After conservation work, the treasure from the Cornish garage will go on display next month, a scruffy star of the museum's Festival of Pots.

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/may/26/pot-found-cornwall-garage-reveals-egypt-excavation-history

Published on May 27, 2014 16:19

History Trivia - King John I of England crowned.

May 27

366 Procopius, Roman usurper against Valens, and member of the Constantinian dynasty was executed.

1153 Malcolm IV became King of Scotland.

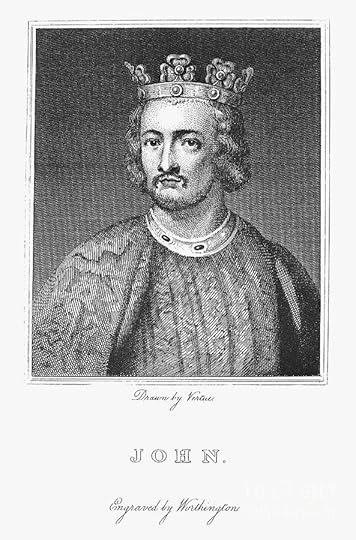

1199 King John I of England crowned.

1328 King Philip VI of France crowned.

1564 John Calvin, one of the dominant figures of the Protestant Reformation, died in Geneva.

366 Procopius, Roman usurper against Valens, and member of the Constantinian dynasty was executed.

1153 Malcolm IV became King of Scotland.

1199 King John I of England crowned.

1328 King Philip VI of France crowned.

1564 John Calvin, one of the dominant figures of the Protestant Reformation, died in Geneva.

Published on May 27, 2014 04:58

May 26, 2014

The mammoth that trampled on the history of mankind

Next month, scientists will meet in the Dordogne to mark the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the La Madeleine mammoth – an engraving on ivory that proves man had lived alongside these prehistoric creatures Robin McKie  Mammoth researcher Professor Adrian Lister with Lyuba, a baby woolly mammoth considered to be the most complete example of the species ever found, at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: Matt Dunham/AP Just a few weeks from now, scientists from across the globe will gather in the town of Les Eyzies in the Dordogne to commemorate one of the most important – and fortuitous – events in the study of human origins. They will congregate to mark the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the Madeleine mammoth, a small piece of ancient art that provided unequivocal proof of the deep antiquity of Homo sapiens.

Mammoth researcher Professor Adrian Lister with Lyuba, a baby woolly mammoth considered to be the most complete example of the species ever found, at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: Matt Dunham/AP Just a few weeks from now, scientists from across the globe will gather in the town of Les Eyzies in the Dordogne to commemorate one of the most important – and fortuitous – events in the study of human origins. They will congregate to mark the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the Madeleine mammoth, a small piece of ancient art that provided unequivocal proof of the deep antiquity of Homo sapiens.

The uncovering of the engraving, in 1864, was the handiwork of a joint British-French archaeological expedition and it provided the first, unambiguous evidence that human beings had once shared this planet with long-extinct animals such as the mammoth. Its discovery was also an act of extraordinary good fortune, it transpires.

"On the day the engraving was found, two of the world's leading palaeontologists happened to be at the site," says Jill Cook, an ice age art expert at the British Museum. "The piece had been fragmented and workmen carrying out the excavations would never have realised this. They would have simply dumped the bits into a bag and forgotten about them."

But by extraordinary good fortune, Edouard Lartet, who was overall director of the dig, and Hugh Falconer, a Scot who was visiting him, were present that day and realised that the bits formed a single item.

"It could so easily have been missed," says Cook. "Indeed, if science could ever be said to have been blessed with a miracle, this would be it."

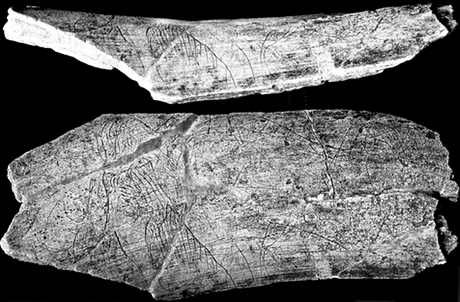

The pieces found at La Madeleine, once glued together, formed a solid, two-inch-thick chunk of mammoth ivory that measured about 9in x 4in. On one side, the ivory had been carefully engraved with lines that Lartet and Falconer realised formed a picture of a mammoth. The discovery was just what Lartet and Falconer – and the excavation's backer, the British philanthropist Henry Christy – had been looking for: proof that Homo sapiens had once shared the planet with these huge, long-extinct creatures, and so must possess deep ancestry as a species.

Evidence had been mounting throughout the 18th century that our planet was incredibly old and that life had existed on it for a very long time – much, much longer than the figure of under 6,000 years that Bishop Ussher had derived in the 17th century for the date of the Earth and all living things. For example, in the 1840s, scientists had begun to realise that rock and gravel deposits found in the Alps and other regions had not been laid down by the flood but were the leftovers of the glaciers and giant icecaps that had covered much of Europe.

Today, we know these events as ice ages, but at the time the period was simply called the reindeer age, because remains of these north dwelling creatures were being found at digs in southern Europe, an indication of the intense cold that must then have enveloped the continent in the distant past, it was argued.

In addition, at several riverbank sites, including one key dig on the banks of the river Somme, in northern France, scientists had excavated human artefacts mixed with the bones of extinct animals such as the mammoth and the woolly rhino. The finds suggested that during the last ice age we might once have shared the landscape with these creatures.

But other scientists disagreed. They argued that the mixing of mammoth fossils and human tools had actually been caused by rivers and flood waters sweeping together different deposits. The mammoth bones had actually been laid down aeons before the human artefacts, they argued, but they had been mixed together by natural forces. In other words, humans did not appear on the scene until long after the mammoth had gone.

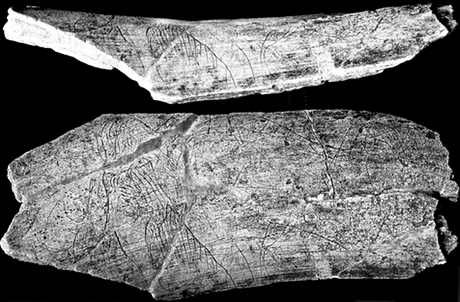

The fragment of ivory, unearthed in 1864, whose fine detail convinced palaeontologists that man had existed far earlier than was previously known. Photograph: Patrick Paillet The excavation at La Madeleine would demolish that notion. The site at Abri de la Madeleine, in the Dordogne, a prehistoric shelter that lies under an overhanging cliff, is made up of well-preserved, distinct layers of deposits that have since been found to contain rich amounts of ancient tools, carvings and fossils of mammoths, woolly rhinos, reindeer and wolverines.

The fragment of ivory, unearthed in 1864, whose fine detail convinced palaeontologists that man had existed far earlier than was previously known. Photograph: Patrick Paillet The excavation at La Madeleine would demolish that notion. The site at Abri de la Madeleine, in the Dordogne, a prehistoric shelter that lies under an overhanging cliff, is made up of well-preserved, distinct layers of deposits that have since been found to contain rich amounts of ancient tools, carvings and fossils of mammoths, woolly rhinos, reindeer and wolverines.

You can see a fine example of a Madeleine carving – of reindeer drawn on a bone – at the British Museum, for example. In addition, at the Natural History Museum's current Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story exhibition, two beautifully engraved bones, found at La Madeleine by Lartet and Christy, are also on display.

"The site has since lent its name to a period known as the Magdalenian era, which thrived across Europe between 12,000 and 16,000 years ago, and which we now appreciate was a time of incredible artistic creativity," says Professor Chris Stringer, curator of the Natural History Museum exhibition.

The site has certainly produced many wonders, but in terms of their sheer scientific importance none can match the splintered mammoth figurine that was spotted by Lartet and Falconer on that day in May 1864. In their hands lay fragments, freshly dug from the earth, of a beautiful engraving of a mammoth, with its distinctive domed head, that was, for good measure, made of mammoth ivory.

"You couldn't really top that in terms of proving that humans had lived at the same time as mammoths," says Stringer. "Indeed, when you examine the piece you can see details of the mammoth's anatomy that we only know about today from the frozen mammoth carcasses that we have found in Siberia."

In other words, only an artist who had shared that ancient landscape (the Madeleine mammoth was carved about 14,000 years ago) with these creatures would have been able to record one with such precision and flair – and on a piece of the animal's own ivory.

"There is no record what the two men said when they realised what they had found, or what they said to Christy when they revealed their discovery to him," adds Cook. "I suspect a lot of claret was drunk in celebration, however."

Certainly, within days, Christy and Lartet had prepared a paper announcing what their expedition had found. This was presented in Paris in June 1864, the event that will be celebrated by the scientists who will gather at Les Eyzies next month.

An illustration of a mammoth hunt, on display at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: The Natural History Museum And there is no doubt that the Madeleine figure is a remarkable work. It has suffered over the millennia, of course – having been broken into fragments before having to endure the indignities of 19th-century conservation, which was not always of the highest standard, says Cook. Nevertheless, it is still clear that the piece was created with confidence and skill by an artist who knew mammoths and understood their behaviour.

An illustration of a mammoth hunt, on display at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: The Natural History Museum And there is no doubt that the Madeleine figure is a remarkable work. It has suffered over the millennia, of course – having been broken into fragments before having to endure the indignities of 19th-century conservation, which was not always of the highest standard, says Cook. Nevertheless, it is still clear that the piece was created with confidence and skill by an artist who knew mammoths and understood their behaviour.

"The large tusks are proportionate and shown in correct perspective," Cook notes in her book, Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind (British Museum Press). "The alert eye is accurately positioned, the trunk is realistic and the lines of the jaw, as well as the dome of the skull, are appropriately massive."

The carving is an example of portable art, which contrasts with the great paintings of horses, rhinos, deer and other animals that were made in situ in caves in the Dordogne and other regions of southern Europe during the palaeolithic period. It was, nevertheless, pretty hefty and was probably kept at the site at La Madeleine, though its exact purpose remains unclear.

"One idea is that the carving was created as a sort of warning," says Cook. "Male elephants go through a period called musth, in which their testosterone levels soar and they become highly aggressive. Mammoths, which were closely related to elephants, probably went through similar bouts of behaviour. The interesting thing about the Madeleine figure is that it has been crafted to suggest movement, possibly as a reminder to fellow tribe members that these could be very dangerous animals.

"Its purpose will never be known for sure, however. On the other hand," says Cook, "there is no doubt about its impact on science and on our understanding of the deep antiquity of our origins. It was overwhelming."

Meanwhile, at the Natural History Museum…The mammoth first appeared in Europe about three million years ago, having evolved from a common ancestor that it shared with the Asian elephant, says Professor Adrian Lister (above), scientific adviser to the Natural History Museum's Mammoth: Ice Age Giants exhibition. "When mammoths arrived here they most probably did not have hair," adds Lister. "That evolved as the planet headed into its recent Quaternary cooling period, which intensified to produce, in the past million years, six major ice ages. Fur would have become very handy then."

Intriguingly, mammoths survived these episodes of intense cooling even though most of Europe was covered with thick sheets of ice. "We have more data about the woolly mammoth than any other extinct creature," says Lister. "We have about 2,000 separate radiocarbon dates for mammoth finds and these show how they responded to the cycles of intense cooling and slow warming."

At the end of each ice age, small clusters of mammoths still clung on in different parts of Euroasia, scientists have found. Numbers slowly recovered as conditions improved. The exception was the last ice age, which began 100,000 years ago and ended about 12,000 years ago. "Mammoth numbers would probably have been very low but would have recovered as they usually did – had it not been for the fact that this time, Europe was populated by tribes of modern human hunters. They probably killed off those endangered survivors."

The star of the Natural History Museum exhibition is undoubtedly Lyuba, a month-old baby woolly mammoth, which died in the Yamal peninsula of Siberia around 42,000 years ago. Her body was buried in wet clay and mud, which then froze, preserving her perfectly until she was found by reindeer herder Yuri Khudi and his sons in 2007. "She is in an absolutely perfect condition," says Lister. "You can see the wonderful detail of her anatomy. It is remarkable."

An example of this anatomical detail is provided by Lyuba's trunk. An elephant's trunk has a D-shaped cross-section but she also has two extra flanges of skin running down the outside of her trunk. "You cannot see that in fossils," added Lister. "You can only see it in these rare examples where soft tissue has been preserved. As to the skin flanges, one speculation is that mammoths used them to scoop snow into their mouths when they were thirsty."

Mammoths: Ice Age Giants runs until 7 September

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/may/25/mammoth-trampled-on-history-of-mankind

Mammoth researcher Professor Adrian Lister with Lyuba, a baby woolly mammoth considered to be the most complete example of the species ever found, at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: Matt Dunham/AP Just a few weeks from now, scientists from across the globe will gather in the town of Les Eyzies in the Dordogne to commemorate one of the most important – and fortuitous – events in the study of human origins. They will congregate to mark the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the Madeleine mammoth, a small piece of ancient art that provided unequivocal proof of the deep antiquity of Homo sapiens.

Mammoth researcher Professor Adrian Lister with Lyuba, a baby woolly mammoth considered to be the most complete example of the species ever found, at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: Matt Dunham/AP Just a few weeks from now, scientists from across the globe will gather in the town of Les Eyzies in the Dordogne to commemorate one of the most important – and fortuitous – events in the study of human origins. They will congregate to mark the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the Madeleine mammoth, a small piece of ancient art that provided unequivocal proof of the deep antiquity of Homo sapiens.The uncovering of the engraving, in 1864, was the handiwork of a joint British-French archaeological expedition and it provided the first, unambiguous evidence that human beings had once shared this planet with long-extinct animals such as the mammoth. Its discovery was also an act of extraordinary good fortune, it transpires.

"On the day the engraving was found, two of the world's leading palaeontologists happened to be at the site," says Jill Cook, an ice age art expert at the British Museum. "The piece had been fragmented and workmen carrying out the excavations would never have realised this. They would have simply dumped the bits into a bag and forgotten about them."

But by extraordinary good fortune, Edouard Lartet, who was overall director of the dig, and Hugh Falconer, a Scot who was visiting him, were present that day and realised that the bits formed a single item.

"It could so easily have been missed," says Cook. "Indeed, if science could ever be said to have been blessed with a miracle, this would be it."

The pieces found at La Madeleine, once glued together, formed a solid, two-inch-thick chunk of mammoth ivory that measured about 9in x 4in. On one side, the ivory had been carefully engraved with lines that Lartet and Falconer realised formed a picture of a mammoth. The discovery was just what Lartet and Falconer – and the excavation's backer, the British philanthropist Henry Christy – had been looking for: proof that Homo sapiens had once shared the planet with these huge, long-extinct creatures, and so must possess deep ancestry as a species.

Evidence had been mounting throughout the 18th century that our planet was incredibly old and that life had existed on it for a very long time – much, much longer than the figure of under 6,000 years that Bishop Ussher had derived in the 17th century for the date of the Earth and all living things. For example, in the 1840s, scientists had begun to realise that rock and gravel deposits found in the Alps and other regions had not been laid down by the flood but were the leftovers of the glaciers and giant icecaps that had covered much of Europe.

Today, we know these events as ice ages, but at the time the period was simply called the reindeer age, because remains of these north dwelling creatures were being found at digs in southern Europe, an indication of the intense cold that must then have enveloped the continent in the distant past, it was argued.

In addition, at several riverbank sites, including one key dig on the banks of the river Somme, in northern France, scientists had excavated human artefacts mixed with the bones of extinct animals such as the mammoth and the woolly rhino. The finds suggested that during the last ice age we might once have shared the landscape with these creatures.

But other scientists disagreed. They argued that the mixing of mammoth fossils and human tools had actually been caused by rivers and flood waters sweeping together different deposits. The mammoth bones had actually been laid down aeons before the human artefacts, they argued, but they had been mixed together by natural forces. In other words, humans did not appear on the scene until long after the mammoth had gone.

The fragment of ivory, unearthed in 1864, whose fine detail convinced palaeontologists that man had existed far earlier than was previously known. Photograph: Patrick Paillet The excavation at La Madeleine would demolish that notion. The site at Abri de la Madeleine, in the Dordogne, a prehistoric shelter that lies under an overhanging cliff, is made up of well-preserved, distinct layers of deposits that have since been found to contain rich amounts of ancient tools, carvings and fossils of mammoths, woolly rhinos, reindeer and wolverines.

The fragment of ivory, unearthed in 1864, whose fine detail convinced palaeontologists that man had existed far earlier than was previously known. Photograph: Patrick Paillet The excavation at La Madeleine would demolish that notion. The site at Abri de la Madeleine, in the Dordogne, a prehistoric shelter that lies under an overhanging cliff, is made up of well-preserved, distinct layers of deposits that have since been found to contain rich amounts of ancient tools, carvings and fossils of mammoths, woolly rhinos, reindeer and wolverines.You can see a fine example of a Madeleine carving – of reindeer drawn on a bone – at the British Museum, for example. In addition, at the Natural History Museum's current Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story exhibition, two beautifully engraved bones, found at La Madeleine by Lartet and Christy, are also on display.

"The site has since lent its name to a period known as the Magdalenian era, which thrived across Europe between 12,000 and 16,000 years ago, and which we now appreciate was a time of incredible artistic creativity," says Professor Chris Stringer, curator of the Natural History Museum exhibition.

The site has certainly produced many wonders, but in terms of their sheer scientific importance none can match the splintered mammoth figurine that was spotted by Lartet and Falconer on that day in May 1864. In their hands lay fragments, freshly dug from the earth, of a beautiful engraving of a mammoth, with its distinctive domed head, that was, for good measure, made of mammoth ivory.

"You couldn't really top that in terms of proving that humans had lived at the same time as mammoths," says Stringer. "Indeed, when you examine the piece you can see details of the mammoth's anatomy that we only know about today from the frozen mammoth carcasses that we have found in Siberia."

In other words, only an artist who had shared that ancient landscape (the Madeleine mammoth was carved about 14,000 years ago) with these creatures would have been able to record one with such precision and flair – and on a piece of the animal's own ivory.

"There is no record what the two men said when they realised what they had found, or what they said to Christy when they revealed their discovery to him," adds Cook. "I suspect a lot of claret was drunk in celebration, however."

Certainly, within days, Christy and Lartet had prepared a paper announcing what their expedition had found. This was presented in Paris in June 1864, the event that will be celebrated by the scientists who will gather at Les Eyzies next month.

An illustration of a mammoth hunt, on display at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: The Natural History Museum And there is no doubt that the Madeleine figure is a remarkable work. It has suffered over the millennia, of course – having been broken into fragments before having to endure the indignities of 19th-century conservation, which was not always of the highest standard, says Cook. Nevertheless, it is still clear that the piece was created with confidence and skill by an artist who knew mammoths and understood their behaviour.

An illustration of a mammoth hunt, on display at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: The Natural History Museum And there is no doubt that the Madeleine figure is a remarkable work. It has suffered over the millennia, of course – having been broken into fragments before having to endure the indignities of 19th-century conservation, which was not always of the highest standard, says Cook. Nevertheless, it is still clear that the piece was created with confidence and skill by an artist who knew mammoths and understood their behaviour."The large tusks are proportionate and shown in correct perspective," Cook notes in her book, Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind (British Museum Press). "The alert eye is accurately positioned, the trunk is realistic and the lines of the jaw, as well as the dome of the skull, are appropriately massive."

The carving is an example of portable art, which contrasts with the great paintings of horses, rhinos, deer and other animals that were made in situ in caves in the Dordogne and other regions of southern Europe during the palaeolithic period. It was, nevertheless, pretty hefty and was probably kept at the site at La Madeleine, though its exact purpose remains unclear.

"One idea is that the carving was created as a sort of warning," says Cook. "Male elephants go through a period called musth, in which their testosterone levels soar and they become highly aggressive. Mammoths, which were closely related to elephants, probably went through similar bouts of behaviour. The interesting thing about the Madeleine figure is that it has been crafted to suggest movement, possibly as a reminder to fellow tribe members that these could be very dangerous animals.

"Its purpose will never be known for sure, however. On the other hand," says Cook, "there is no doubt about its impact on science and on our understanding of the deep antiquity of our origins. It was overwhelming."

Meanwhile, at the Natural History Museum…The mammoth first appeared in Europe about three million years ago, having evolved from a common ancestor that it shared with the Asian elephant, says Professor Adrian Lister (above), scientific adviser to the Natural History Museum's Mammoth: Ice Age Giants exhibition. "When mammoths arrived here they most probably did not have hair," adds Lister. "That evolved as the planet headed into its recent Quaternary cooling period, which intensified to produce, in the past million years, six major ice ages. Fur would have become very handy then."

Intriguingly, mammoths survived these episodes of intense cooling even though most of Europe was covered with thick sheets of ice. "We have more data about the woolly mammoth than any other extinct creature," says Lister. "We have about 2,000 separate radiocarbon dates for mammoth finds and these show how they responded to the cycles of intense cooling and slow warming."

At the end of each ice age, small clusters of mammoths still clung on in different parts of Euroasia, scientists have found. Numbers slowly recovered as conditions improved. The exception was the last ice age, which began 100,000 years ago and ended about 12,000 years ago. "Mammoth numbers would probably have been very low but would have recovered as they usually did – had it not been for the fact that this time, Europe was populated by tribes of modern human hunters. They probably killed off those endangered survivors."

The star of the Natural History Museum exhibition is undoubtedly Lyuba, a month-old baby woolly mammoth, which died in the Yamal peninsula of Siberia around 42,000 years ago. Her body was buried in wet clay and mud, which then froze, preserving her perfectly until she was found by reindeer herder Yuri Khudi and his sons in 2007. "She is in an absolutely perfect condition," says Lister. "You can see the wonderful detail of her anatomy. It is remarkable."

An example of this anatomical detail is provided by Lyuba's trunk. An elephant's trunk has a D-shaped cross-section but she also has two extra flanges of skin running down the outside of her trunk. "You cannot see that in fossils," added Lister. "You can only see it in these rare examples where soft tissue has been preserved. As to the skin flanges, one speculation is that mammoths used them to scoop snow into their mouths when they were thirsty."

Mammoths: Ice Age Giants runs until 7 September

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/may/25/mammoth-trampled-on-history-of-mankind

Published on May 26, 2014 14:13