MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 256

July 22, 2014

Going West Wasn't So Deadly for Early Mormon Pioneers

By Stephanie Pappas

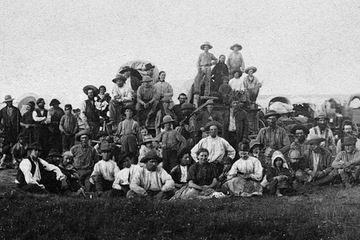

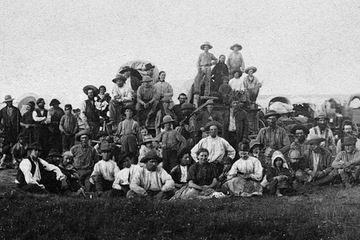

A group of Mormon pioneers pose for a photo at South Pass, Wyoming in about 1859.

A group of Mormon pioneers pose for a photo at South Pass, Wyoming in about 1859.

Credit: Charles Roscoe Savage, courtesy of the Harold B. Lee LibrarySnakebites. Disease. Wolves. Exposure.

Pioneers who headed West during the 1800s had plenty to fear, but a new study finds that at least one group of these migrants — early Mormons — did just fine on their trek to Salt Lake City.

An analysis of historical records reveals that the mortality rate for early Mormon pioneers was a mere 3.5 percent, hardly higher than the national mortality rate at the time. The average American between the 1840s and 1860s, when the Mormon pioneers were heading West, had between a 2.5 percent and 2.9 percent chance of dying in a given year.

"This is one of the first definitive analyses with the most up-to-date data regarding how many people were in this immigration, how many pioneers died and the breakdowns of these deaths," study researcher Dennis Tolley, a statistician at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, said in a statement.

Mormon migration

Joseph Smith founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (or LDS Church) in 1830. Smith and his followers were often discriminated against, and Smith himself was killed by a mob in 1844.

The founder's successor, Brigham Young, organized the fledgling religious group, calling for a western migration into what was then Mexico and what is now Utah. Between 1847 and 1868, more than 60,000 Mormons made the journey, according to LDS Church history. Many traveled by wagon train; a few walked, carrying their belongings (and sometimes their family members) in wheelbarrow-like handcarts.

These handcart travelers provide some of the most harrowing tales of the migration. Ten groups of handcart-toting pioneers made the journey to Salt Lake City between 1856 and 1860, according to church histories. Eight arrived more or less safely. The two largest, the Willie and Martin handcart companies, met with a disaster that rivaled that of the infamous "Donner Party," a group of (non-Mormon) pioneers who became stranded in California in 1846 and resorted to cannibalism.

James G. Willie and Edward Martin led 500 and 665 pioneers, respectively. The groups got a late start, however, and didn't leave the area that is now Omaha until August. By October, the companies were stranded in Wyoming, dying of cold, hunger and disease. Rescue parties from Salt Lake City saved many, but more than 200 people lost their lives.

Safe travels

The story of the Willie and Martin companies is a tragic one, and modern Mormons often memorialize it with recreations of short handcart journeys. But only 5 percent of Mormon pioneers made the passage West by handcart, Tolley and his colleagues said in a statement.

"The [Mormon] youth go out and learn that a lot of people died, and they push the handcart, and after three days they think they are practically dead,” study researcher and retired LDS Church historian Mel Bashore said in the statement. "But most people traveled in wagons to Utah. The whole Mormon trail movement that spanned 20 years was a really successful endeavor."

Bashore and Tolley analyzed 56,000 records of pioneers who traveled to Salt Lake City between 1847 and 1868. The researchers found 1,900 deaths during the journey or within the calendar year of arrival in Salt Lake, making the overall mortality rate 3.5 percent.

Disease was a major killer, followed by accidents such as being trampled by livestock or run over by a wagon, the researchers reported. Four pioneers were killed by Native Americans; two died from snakebites or scorpion stings; one was murdered, and two were — yikes — eaten by wolves.

Taken alone, the Willie and Martin companies had a 16.5 percent mortality rate, and handcart travel in general was more perilous than journeying by wagon. Handcart pioneers died at a rate of 4.7 percent, compared to a 3.5 percent mortality rate for pioneers with wagons.

"Those travelling with handcarts were presumably poorer, malnourished and all sorts of other factors," Tolley said. These factors would have affected their morality rate.

The mortality rate for women was 3.6 percent, compared to 3.3 percent for men. The youngest immigrants fared best: Those under age 20 had only a 1.75 percent mortality rate.

The findings will appear in an upcoming issue of the journal BYU Studies, which focuses on LDS Church history and teachings.

http://www.livescience.com/46834-mormon-pioneers-mortality-rate.html

A group of Mormon pioneers pose for a photo at South Pass, Wyoming in about 1859.

A group of Mormon pioneers pose for a photo at South Pass, Wyoming in about 1859.Credit: Charles Roscoe Savage, courtesy of the Harold B. Lee LibrarySnakebites. Disease. Wolves. Exposure.

Pioneers who headed West during the 1800s had plenty to fear, but a new study finds that at least one group of these migrants — early Mormons — did just fine on their trek to Salt Lake City.

An analysis of historical records reveals that the mortality rate for early Mormon pioneers was a mere 3.5 percent, hardly higher than the national mortality rate at the time. The average American between the 1840s and 1860s, when the Mormon pioneers were heading West, had between a 2.5 percent and 2.9 percent chance of dying in a given year.

"This is one of the first definitive analyses with the most up-to-date data regarding how many people were in this immigration, how many pioneers died and the breakdowns of these deaths," study researcher Dennis Tolley, a statistician at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, said in a statement.

Mormon migration

Joseph Smith founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (or LDS Church) in 1830. Smith and his followers were often discriminated against, and Smith himself was killed by a mob in 1844.

The founder's successor, Brigham Young, organized the fledgling religious group, calling for a western migration into what was then Mexico and what is now Utah. Between 1847 and 1868, more than 60,000 Mormons made the journey, according to LDS Church history. Many traveled by wagon train; a few walked, carrying their belongings (and sometimes their family members) in wheelbarrow-like handcarts.

These handcart travelers provide some of the most harrowing tales of the migration. Ten groups of handcart-toting pioneers made the journey to Salt Lake City between 1856 and 1860, according to church histories. Eight arrived more or less safely. The two largest, the Willie and Martin handcart companies, met with a disaster that rivaled that of the infamous "Donner Party," a group of (non-Mormon) pioneers who became stranded in California in 1846 and resorted to cannibalism.

James G. Willie and Edward Martin led 500 and 665 pioneers, respectively. The groups got a late start, however, and didn't leave the area that is now Omaha until August. By October, the companies were stranded in Wyoming, dying of cold, hunger and disease. Rescue parties from Salt Lake City saved many, but more than 200 people lost their lives.

Safe travels

The story of the Willie and Martin companies is a tragic one, and modern Mormons often memorialize it with recreations of short handcart journeys. But only 5 percent of Mormon pioneers made the passage West by handcart, Tolley and his colleagues said in a statement.

"The [Mormon] youth go out and learn that a lot of people died, and they push the handcart, and after three days they think they are practically dead,” study researcher and retired LDS Church historian Mel Bashore said in the statement. "But most people traveled in wagons to Utah. The whole Mormon trail movement that spanned 20 years was a really successful endeavor."

Bashore and Tolley analyzed 56,000 records of pioneers who traveled to Salt Lake City between 1847 and 1868. The researchers found 1,900 deaths during the journey or within the calendar year of arrival in Salt Lake, making the overall mortality rate 3.5 percent.

Disease was a major killer, followed by accidents such as being trampled by livestock or run over by a wagon, the researchers reported. Four pioneers were killed by Native Americans; two died from snakebites or scorpion stings; one was murdered, and two were — yikes — eaten by wolves.

Taken alone, the Willie and Martin companies had a 16.5 percent mortality rate, and handcart travel in general was more perilous than journeying by wagon. Handcart pioneers died at a rate of 4.7 percent, compared to a 3.5 percent mortality rate for pioneers with wagons.

"Those travelling with handcarts were presumably poorer, malnourished and all sorts of other factors," Tolley said. These factors would have affected their morality rate.

The mortality rate for women was 3.6 percent, compared to 3.3 percent for men. The youngest immigrants fared best: Those under age 20 had only a 1.75 percent mortality rate.

The findings will appear in an upcoming issue of the journal BYU Studies, which focuses on LDS Church history and teachings.

http://www.livescience.com/46834-mormon-pioneers-mortality-rate.html

Published on July 22, 2014 16:02

Tooth Tales: Prehistoric Plaque Reveals Early Humans Ate Weeds

By Laura Geggel

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.

Credit: Donatella Usai/Centro Studi Sudanesi and Sub-Sahariani (CSSeS)

When looking for a meal, prehistoric people in Africa munched on the tuberous roots of weeds such as the purple nutsedge, according to a new study of hardened plaque on samples of ancient teeth.

Researchers examined the dental buildup of 14 people buried at Al Khiday, an archeological site near the Nile River in central Sudan. The skeletons date back to between about 6,700 B.C., when prehistoric people relied on hunting and gathering, to agricultural times, at about the beginning of the first millennium B.C.

The researchers collected samples of the individuals' dental calculus, the hardened grime that forms when plaque accumulates and mineralizes on teeth. Such buildup is fairly common in prehistoric skeletons, the researchers said

[image error]

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.

Credit: Donatella Usai/Centro Studi Sudanesi and Sub-Sahariani (CSSeS) View full size image

When looking for a meal, prehistoric people in Africa munched on the tuberous roots of weeds such as the purple nutsedge, according to a new study of hardened plaque on samples of ancient teeth.

Researchers examined the dental buildup of 14 people buried at Al Khiday, an archeological site near the Nile River in central Sudan. The skeletons date back to between about 6,700 B.C., when prehistoric people relied on hunting and gathering, to agricultural times, at about the beginning of the first millennium B.C.

The researchers collected samples of the individuals' dental calculus, the hardened grime that forms when plaque accumulates and mineralizes on teeth. Such buildup is fairly common in prehistoric skeletons, the researchers said. [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

"The oral hygiene activities were not as good as they are today," lead researcher Karen Hardy, a professor of prehistoric archeology at the Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain, told Live Science.

An analysis of the chemical compounds and microfossils in the dental calculus point to the purple nutsedge (Cyperus rotundus), Hardy said. In the teeth of each of the skeletons, Harder and her colleagues found starch granules that share a chemical composition with nutsedge. A close look at the granules also revealed how these people likely prepared their food: Those from the earlier time period likely ate the plant raw or lightly heated, which would have helped make the roots easier to peel.

In contrast, granules from the Neolithic period, beginning in about 4,500 B.C. in central Sudan, are cracked and enlarged, suggesting that people may have ground or roasted these granules over a fire.

[image error] The hardened dental calculus on prehistoric teeth suggests that people ate purple nutsedge, a weedy plant rich in carbohydrates.

The hardened dental calculus on prehistoric teeth suggests that people ate purple nutsedge, a weedy plant rich in carbohydrates.

Credit: Buckley S, Usai D, Jakob T, Radini A, Hardy K (2014) Dental Calculus Reveals Unique Insights into Food Items, Cooking and Plant Processing in Prehistoric Central Sudan. PLoS ONE 9(7): e100808. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100808

View full size imageIt's difficult, however, to determine how prehistoric people prepared their meals based on the present appearance of starch granules, said John Dudgeon, an associate professor of anthropology at Idaho State University in Pocatello, who was not involved in the study. Further research may help scientists determine whether the food was roasted or boiled, or if it simply degraded on its own.

"Starches are particularly sensitive," Dudgeonsaid. They fall apart as soon a person begins chewing on them. "The fact that they even survive in the dental calculus in the teeth is amazing."

However, he commended the researchers for their detailed work in matching the chemical analysis of the purple nutsedge to the fragments found in the dental calculus. "It provides a novel way to look at the micro-residues on the skeleton," Dudgeon said. "This a pretty good way to fingerprint what that material is that is coming out of the calculus."

It's unclear why prehistoric people chewed on the tubers, but other ancient societies have benefited from the plant's many uses. Hunter-gatherer societies, such as the Aboriginals in central Australia, relied on these tubers for carbohydrates, and studies show that the plant contains lysine, an essential amino acid that the human body cannot produce on its own.

The ancient Egyptians and Greeks used purple nutsedge for water purification, perfume and medical purposes, records suggest. What's more, the plant has antimicrobial, antimalarial, antioxidant and anti-diabetic compounds, studies have found.

In high concentrations, purple nutsedge also inhibits atype of bacteria that leads to tooth decay.This may explain why researchers have found fewer cavities in the Al Khiday individuals at the turn of the first millennium B.C., compared to their counterparts at Gabati, an archeological site to the north, Hardy said. Still, more research is needed to examine indicators of dental hygiene in these areas.

Though purple nutsedge and its related sedge species are rich in carbohydrates, modern-day farmers consider these plants a nuisance. The slender-stemmed, flowering nutsedge has deep, tuberous roots that are hard to pull out of soil.

"It’s a veggie, weedy thing," Hardy says. "It’s very prolific. That's why it's such a problem for farmers today."

Purple nutsedge typically grows in tropical areas. In the 1980s, researchers found that the plant's tubers taste bitter when grown in wet areas, but reported that the taste improved when the weed was planted in drier places. Though the plant is no longer a common carbohydrate snack, people still use it today for herbal medicine in the Middle East, Far East and India, Hardy said.

http://www.livescience.com/46836-prehistoric-tooth-plaque-diet.html

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.Credit: Donatella Usai/Centro Studi Sudanesi and Sub-Sahariani (CSSeS)

When looking for a meal, prehistoric people in Africa munched on the tuberous roots of weeds such as the purple nutsedge, according to a new study of hardened plaque on samples of ancient teeth.

Researchers examined the dental buildup of 14 people buried at Al Khiday, an archeological site near the Nile River in central Sudan. The skeletons date back to between about 6,700 B.C., when prehistoric people relied on hunting and gathering, to agricultural times, at about the beginning of the first millennium B.C.

The researchers collected samples of the individuals' dental calculus, the hardened grime that forms when plaque accumulates and mineralizes on teeth. Such buildup is fairly common in prehistoric skeletons, the researchers said

[image error]

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.

Researchers studied the dental calculus of skeletons, such as this one of a young man, found at a prehistoric gravesite in central Sudan.Credit: Donatella Usai/Centro Studi Sudanesi and Sub-Sahariani (CSSeS) View full size image

When looking for a meal, prehistoric people in Africa munched on the tuberous roots of weeds such as the purple nutsedge, according to a new study of hardened plaque on samples of ancient teeth.

Researchers examined the dental buildup of 14 people buried at Al Khiday, an archeological site near the Nile River in central Sudan. The skeletons date back to between about 6,700 B.C., when prehistoric people relied on hunting and gathering, to agricultural times, at about the beginning of the first millennium B.C.

The researchers collected samples of the individuals' dental calculus, the hardened grime that forms when plaque accumulates and mineralizes on teeth. Such buildup is fairly common in prehistoric skeletons, the researchers said. [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

"The oral hygiene activities were not as good as they are today," lead researcher Karen Hardy, a professor of prehistoric archeology at the Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain, told Live Science.

An analysis of the chemical compounds and microfossils in the dental calculus point to the purple nutsedge (Cyperus rotundus), Hardy said. In the teeth of each of the skeletons, Harder and her colleagues found starch granules that share a chemical composition with nutsedge. A close look at the granules also revealed how these people likely prepared their food: Those from the earlier time period likely ate the plant raw or lightly heated, which would have helped make the roots easier to peel.

In contrast, granules from the Neolithic period, beginning in about 4,500 B.C. in central Sudan, are cracked and enlarged, suggesting that people may have ground or roasted these granules over a fire.

[image error]

The hardened dental calculus on prehistoric teeth suggests that people ate purple nutsedge, a weedy plant rich in carbohydrates.

The hardened dental calculus on prehistoric teeth suggests that people ate purple nutsedge, a weedy plant rich in carbohydrates.Credit: Buckley S, Usai D, Jakob T, Radini A, Hardy K (2014) Dental Calculus Reveals Unique Insights into Food Items, Cooking and Plant Processing in Prehistoric Central Sudan. PLoS ONE 9(7): e100808. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100808

View full size imageIt's difficult, however, to determine how prehistoric people prepared their meals based on the present appearance of starch granules, said John Dudgeon, an associate professor of anthropology at Idaho State University in Pocatello, who was not involved in the study. Further research may help scientists determine whether the food was roasted or boiled, or if it simply degraded on its own.

"Starches are particularly sensitive," Dudgeonsaid. They fall apart as soon a person begins chewing on them. "The fact that they even survive in the dental calculus in the teeth is amazing."

However, he commended the researchers for their detailed work in matching the chemical analysis of the purple nutsedge to the fragments found in the dental calculus. "It provides a novel way to look at the micro-residues on the skeleton," Dudgeon said. "This a pretty good way to fingerprint what that material is that is coming out of the calculus."

It's unclear why prehistoric people chewed on the tubers, but other ancient societies have benefited from the plant's many uses. Hunter-gatherer societies, such as the Aboriginals in central Australia, relied on these tubers for carbohydrates, and studies show that the plant contains lysine, an essential amino acid that the human body cannot produce on its own.

The ancient Egyptians and Greeks used purple nutsedge for water purification, perfume and medical purposes, records suggest. What's more, the plant has antimicrobial, antimalarial, antioxidant and anti-diabetic compounds, studies have found.

In high concentrations, purple nutsedge also inhibits atype of bacteria that leads to tooth decay.This may explain why researchers have found fewer cavities in the Al Khiday individuals at the turn of the first millennium B.C., compared to their counterparts at Gabati, an archeological site to the north, Hardy said. Still, more research is needed to examine indicators of dental hygiene in these areas.

Though purple nutsedge and its related sedge species are rich in carbohydrates, modern-day farmers consider these plants a nuisance. The slender-stemmed, flowering nutsedge has deep, tuberous roots that are hard to pull out of soil.

"It’s a veggie, weedy thing," Hardy says. "It’s very prolific. That's why it's such a problem for farmers today."

Purple nutsedge typically grows in tropical areas. In the 1980s, researchers found that the plant's tubers taste bitter when grown in wet areas, but reported that the taste improved when the weed was planted in drier places. Though the plant is no longer a common carbohydrate snack, people still use it today for herbal medicine in the Middle East, Far East and India, Hardy said.

http://www.livescience.com/46836-prehistoric-tooth-plaque-diet.html

Published on July 22, 2014 15:57

Clay Tokens Used As 'Contracts' Even After Invention of Writing

By Elizabeth Palermo

These clay tokens were found at a dig site in Turkey. Archaeologists think they were used as part of ancient system of record-keeping.

These clay tokens were found at a dig site in Turkey. Archaeologists think they were used as part of ancient system of record-keeping.

Credit: Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project

Archaeologists in Turkey recently unearthed what they say is proof that, thousands of years after the invention of a formal writing system, the ancient people of the Middle East continued to use a more primitive way of recording information: clay tokens.

Researchers at Ziyaret Tepe — the site of the ancient provincial capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — recently discovered nearly 500 of these tokens, which they think were once used by administrators as part of an ancient "bookkeeping" system.

It has long been believed that clay tokens, which were often used to represent units of commodities such as livestock or grain, were only circulated in the period leading up to around 3,000 B.C., when they were replaced by a more elaborate writing system, called cuneiform script. However, the tokens that researchers found at Ziyaret Tepe date back as early as around 1,000 B.C., which suggests that these ancient artifacts were still in use thousands of years after cuneiform was invented

The Neo-Assyrian Empire lasted from about 900 B.C. to 600 B.C., and at its height, grew to become a vast and powerful state.

Ancient record-keeping

John MacGinnis, a research fellow with the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom and lead researcher for the study, said this simultaneous use of both a writing system and a more primitive recording system isn't as strange as one might think. He compared it to the continued use of pens in the age of the computer.

"Complex writing didn't stop the use of the abacus, just as the digital age hasn't wiped out pencils and pens," MacGinnis said in a statement. "In fact, in a literate society, there are multiple channels of recording information that can be complementary to each other. In this case, both prehistoric clay tokens and cuneiform writing [were] used together."

Cinzia Pappi, an archaeologist at Leipzig Universityin Germany, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the discovery of tokens at Ziyaret Tepe is a reminder that major historical developments, such as the invention of writing systems, are not always linear.

"The Neo-Assyrian empire at this time [the first millennium] had reached an almost unprecedented level of social and economic complexity, during which cuneiform began to compete with alphabetic writing to record any number of languages in use," Pappi said. "The new evidence shows not only that all of these recording systems can occur side by side and fulfill complementary roles, but promises a new view of the ways in which the various peoples of the Neo-Assyrian Empire interacted and participated in economic life."

Exchanging tokens

MacGinnis and a team of researchers associated with the Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project think that originally, the Assyrians used clay tokens to establish a kind of contract between buyers and sellers.

"The use of tokens in what were certified records (perhaps indeed, effectively contracts), is from the late fourth millennium," MacGinnis told Live Science in an email. He went on to say that these early tokens were typically sealed in bullae, or clay containers, where they served as a permanent record of a transaction.

Previous research on the use of clay tokens supports this belief, and focuses on their role as antecedents to cuneiform writing. According to MacGinnis, scholars of ancient near-Eastern societies maintain that the use of such tokens for this purpose dropped off after the fourth millennium B.C. [Album: The Seven Ancient Wonders of the World]

The tokens were typically seen as a sort of "direct evolutionary precursor to writing," Pappi said.

"What remains unclear," Pappi said, "is what their exact role might have been within complex societies where writing was long established."

But MacGinnis and his fellow researchers think they have solved this puzzle. The archaeologists say the new findings provide evidence that clay tokens were being used alongside cuneiform writing in the first millennium B.C., and that their role was distinctly administrative.

A way to trade

The tokens were found in what is believed to have been the main administrative building in the lower town of Tušhan, MacGinnis said. More than 300 tokens were found in two rooms near the back of the building, which MacGinnis said resembles a delivery area or ancient loading bay. Along with the tokens, MacGinnis' team uncovered weights, storage vessels, clay sealing and cuneiform archives.

While archaeologists are still not entirely sure what the tokens represented, they think the clay pieces likely signified various quantities of grain or heads of livestock.

"We think one of two things happened here," MacGinnis said. "You either have information about livestock coming though here, or flocks of animals themselves. Each farmer or herder would have a bag with tokens to represent their flock."

Most of the cuneiform tablets that correspond with the recently unearthed tokens deal with trades of grain, MacGinnis said. As he explained, by using tokens in conjunction with cuneiform tablets or records, the ancient Assyrians developed a system of recording information that was ideal for administrative purposes.

"The tokens provided a system of movable numbers that allowed for stock to be moved, and accounts to be modified and updated, without committing to writing — a system that doesn't require everyone involved to be literate," MacGinnis said.

Such a system may have also been ideal in a society in which writing required a sophisticated education and was generally restricted to elites, according to Pappi.

"It is possible that these tokens thus reflect administrative systems at different levels of literate and nonliterate society," Pappi said.

Place in history

Both MacGinnis and Pappi noted a previous discovery of clay tokens at Nuzi, an excavation site near Kirkuk, Iraq, that dated back to the late second millennium B.C., after the advent of writing.

But the new research, MacGinnis said, is the first to put forth the idea that, as early as the first millennium B.C., the use of tokens in the Assyrian Empire was flourishing.

And while most scholars have focused on the role of tokens in earlier periods, the artifacts from the Ziyaret Tepe site add an exciting dimension to the discussion of Assyrian administrative systems, MacGinnis said.

"The inventions of recording systems are milestones in the human journey, and any finds which contribute to the understanding of how they came about makes a basic contribution to mapping the progress of mankind," MacGinnis said.

Details of the new finding will be published in an upcoming issue of the Cambridge Archaeological Journal. The Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project, which led the study, is directed by Timothy Matney of the University of Akron in Ohio. Dirk Wicke, of the University of Mainz in Germany; and Willis Monroe, of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, also contributed to the research.

http://www.livescience.com/46832-clay-tokens-ancient-bookkeeping.html

These clay tokens were found at a dig site in Turkey. Archaeologists think they were used as part of ancient system of record-keeping.

These clay tokens were found at a dig site in Turkey. Archaeologists think they were used as part of ancient system of record-keeping.Credit: Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project

Archaeologists in Turkey recently unearthed what they say is proof that, thousands of years after the invention of a formal writing system, the ancient people of the Middle East continued to use a more primitive way of recording information: clay tokens.

Researchers at Ziyaret Tepe — the site of the ancient provincial capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire — recently discovered nearly 500 of these tokens, which they think were once used by administrators as part of an ancient "bookkeeping" system.

It has long been believed that clay tokens, which were often used to represent units of commodities such as livestock or grain, were only circulated in the period leading up to around 3,000 B.C., when they were replaced by a more elaborate writing system, called cuneiform script. However, the tokens that researchers found at Ziyaret Tepe date back as early as around 1,000 B.C., which suggests that these ancient artifacts were still in use thousands of years after cuneiform was invented

The Neo-Assyrian Empire lasted from about 900 B.C. to 600 B.C., and at its height, grew to become a vast and powerful state.

Ancient record-keeping

John MacGinnis, a research fellow with the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom and lead researcher for the study, said this simultaneous use of both a writing system and a more primitive recording system isn't as strange as one might think. He compared it to the continued use of pens in the age of the computer.

"Complex writing didn't stop the use of the abacus, just as the digital age hasn't wiped out pencils and pens," MacGinnis said in a statement. "In fact, in a literate society, there are multiple channels of recording information that can be complementary to each other. In this case, both prehistoric clay tokens and cuneiform writing [were] used together."

Cinzia Pappi, an archaeologist at Leipzig Universityin Germany, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the discovery of tokens at Ziyaret Tepe is a reminder that major historical developments, such as the invention of writing systems, are not always linear.

"The Neo-Assyrian empire at this time [the first millennium] had reached an almost unprecedented level of social and economic complexity, during which cuneiform began to compete with alphabetic writing to record any number of languages in use," Pappi said. "The new evidence shows not only that all of these recording systems can occur side by side and fulfill complementary roles, but promises a new view of the ways in which the various peoples of the Neo-Assyrian Empire interacted and participated in economic life."

Exchanging tokens

MacGinnis and a team of researchers associated with the Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project think that originally, the Assyrians used clay tokens to establish a kind of contract between buyers and sellers.

"The use of tokens in what were certified records (perhaps indeed, effectively contracts), is from the late fourth millennium," MacGinnis told Live Science in an email. He went on to say that these early tokens were typically sealed in bullae, or clay containers, where they served as a permanent record of a transaction.

Previous research on the use of clay tokens supports this belief, and focuses on their role as antecedents to cuneiform writing. According to MacGinnis, scholars of ancient near-Eastern societies maintain that the use of such tokens for this purpose dropped off after the fourth millennium B.C. [Album: The Seven Ancient Wonders of the World]

The tokens were typically seen as a sort of "direct evolutionary precursor to writing," Pappi said.

"What remains unclear," Pappi said, "is what their exact role might have been within complex societies where writing was long established."

But MacGinnis and his fellow researchers think they have solved this puzzle. The archaeologists say the new findings provide evidence that clay tokens were being used alongside cuneiform writing in the first millennium B.C., and that their role was distinctly administrative.

A way to trade

The tokens were found in what is believed to have been the main administrative building in the lower town of Tušhan, MacGinnis said. More than 300 tokens were found in two rooms near the back of the building, which MacGinnis said resembles a delivery area or ancient loading bay. Along with the tokens, MacGinnis' team uncovered weights, storage vessels, clay sealing and cuneiform archives.

While archaeologists are still not entirely sure what the tokens represented, they think the clay pieces likely signified various quantities of grain or heads of livestock.

"We think one of two things happened here," MacGinnis said. "You either have information about livestock coming though here, or flocks of animals themselves. Each farmer or herder would have a bag with tokens to represent their flock."

Most of the cuneiform tablets that correspond with the recently unearthed tokens deal with trades of grain, MacGinnis said. As he explained, by using tokens in conjunction with cuneiform tablets or records, the ancient Assyrians developed a system of recording information that was ideal for administrative purposes.

"The tokens provided a system of movable numbers that allowed for stock to be moved, and accounts to be modified and updated, without committing to writing — a system that doesn't require everyone involved to be literate," MacGinnis said.

Such a system may have also been ideal in a society in which writing required a sophisticated education and was generally restricted to elites, according to Pappi.

"It is possible that these tokens thus reflect administrative systems at different levels of literate and nonliterate society," Pappi said.

Place in history

Both MacGinnis and Pappi noted a previous discovery of clay tokens at Nuzi, an excavation site near Kirkuk, Iraq, that dated back to the late second millennium B.C., after the advent of writing.

But the new research, MacGinnis said, is the first to put forth the idea that, as early as the first millennium B.C., the use of tokens in the Assyrian Empire was flourishing.

And while most scholars have focused on the role of tokens in earlier periods, the artifacts from the Ziyaret Tepe site add an exciting dimension to the discussion of Assyrian administrative systems, MacGinnis said.

"The inventions of recording systems are milestones in the human journey, and any finds which contribute to the understanding of how they came about makes a basic contribution to mapping the progress of mankind," MacGinnis said.

Details of the new finding will be published in an upcoming issue of the Cambridge Archaeological Journal. The Ziyaret Tepe Archaeological Project, which led the study, is directed by Timothy Matney of the University of Akron in Ohio. Dirk Wicke, of the University of Mainz in Germany; and Willis Monroe, of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, also contributed to the research.

http://www.livescience.com/46832-clay-tokens-ancient-bookkeeping.html

Published on July 22, 2014 15:50

Ancient priest's tomb painting discovered near Great Pyramid at Giza

A painting discovered in the tomb of a priest, just 1,000 feet from the Great Pyramid at Giza in Egypt depicts scenes of ancient life.Photo courtesy Maksim Lebedev http://www.foxnews.com/science/2014/07/16/ancient-priest-tomb-painting-discovered-near-great-pyramid-at-giza/

A painting discovered in the tomb of a priest, just 1,000 feet from the Great Pyramid at Giza in Egypt depicts scenes of ancient life.Photo courtesy Maksim Lebedev http://www.foxnews.com/science/2014/07/16/ancient-priest-tomb-painting-discovered-near-great-pyramid-at-giza/By Owen Jarus

A wall painting, dating back over 4,300 years, has been discovered in a tomb located just east of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The painting shows vivid scenes of life, including boats sailing south on the Nile River, a bird hunting trip in a marsh and a man named Perseneb who's shown with his wife and dog.

While Giza is famous for its pyramids, the site also contains fields of tombs that sprawl to the east and west of the Great Pyramid. These tombs were created for private individuals who held varying degrees of rank and power during the Old Kingdom (2649-2150 B.C.), the age when the Giza pyramids were built. [See Images of the Painting and Giza Tomb]

The new painting was discovered in 2012 by a team from the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, which has been excavating these tombs since 1996.

A surprise discovery

Scientists discovered the painting when they began restoring the tomb of Perseneb, a man who was a "priest" and "steward," according to the tomb's inscriptions.

His tomb, located 1,000 feet east of the Great Pyramid of Giza, contains an offering room, central room and burial chamber. The three rooms contain 11 statues showing depictions of Perseneb and members of his family. First recorded in the 19th century by the German explorer Karl Richard Lepsius and French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, the tomb is believed to date to the middle or late fifth dynasty (ca. 2450-2350 B.C.). The fifth dynasty is a time period within the Old Kingdom.

"Known since the 19thcentury, the [tomb] could hardly present any new principal features. Therefore, it was a real surprise to discoveran Old Kingdom painting on the eastern wall of the central room," wrote Maksim Lebedev, a reader (the American equivalent is a professor) at the Russian State University for the Humanities, in an email to Live Science.

"The painting was made on a thin layer of fine white plaster darkened with 19th-century soot and dirt.By the time of recording, only about 30 percent of the original plaster had preserved on the wall," Lebedev said.

Since the 19th century, the growth and industrialization of Cairo has led to problems with pollution at Giza. And the fact that people were actually living inside the tomb in some periods (including the Middle Ages) also damaged the painting, Lebedev said.

Nevertheless, "none of the scenes has been lost completely. The remaining traces allow [for the] reconstruction [of] the whole composition," Lebedev said.

Scenes of life

The reconstructed painting reflects ancient life. At the top of the painting there are images of boats sailing the Nile River, their sails pointing south. They "probably represent the return of the owner from the north after a pilgrimage or inspection of his funerary estates," Lebedev said. Funerary estates were tax-exempt property left by the deceased to help support surviving dependents and the upkeep of his tomb. [Photos: Amazing Discoveries at Egypt's Giza Pyramids]

The painting's "two lower registers preserved representations of various agricultural scenes: plowing, sowing, workers driving sheep over sown seed, driving donkeys laden with sheaves to the threshing floor," Lebedev said.

The painting also shows an image of Perseneb, his wife and what appears to be his dog. There is also a marsh scene with a man on a boat who appears to be bird hunting.

"All the depicted scenes had important symbolic meanings. Fowling (bird hunting) in the marshland could refer to the ideas of rebirth and taming of chaotic forces," Lebedev said. "The full agricultural sequence relating to crops represents the most crucial event in the life of ancient Egyptian society," he added. Also, the representation of "boats with sails going southwards is another important tomb subject, which reflected the high status of the person."

More discoveries to come

The area the Russian team has been excavating contains a number of tombs that may hold undiscovered wall paintings. The team has found indirect evidence for paintings in some tombs, such as very smooth walls and remains of wall plaster and paint, Lebedev said.

"Since many rock-cut chapels of the eastern edge of the Giza plateau were rapidly excavated or just recorded [without excavation] in the first half of the 20th century, sometimes without sufficient documentation, and still covered with thick layers of rough plaster left from later inhabitants [who lived in the tombs], one may expect that more paintings will be discovered in this part of the necropolis."

The tomb of Perseneb was partly restored by the Russian mission in 2013. The work was supported by a donation from the Thames Valley Ancient Egyptian Society in the United Kingdom.

The painting reconstructions will be published, in full, in a scholarly publication in the future. The images on Live Science show just a few of the reconstructed scenes.

Published on July 22, 2014 15:44

Mr. Chuckles has his paws on The Evolution Trilogy by Vanessa Wester whilst stirring the Wizard's Cauldron

The Wizard speaks

WARNING - This is an EXCLUSIVE!!!! "It has only had one edit and the book is nowhere near completion yet… "

Read the extract and more about Vanessa at:

http://greenwizard62.blogspot.co.uk/2014/07/evolution-trilogy-author-vanessa-wester.html

Published on July 22, 2014 15:31

Mr. Chuckles has his paws on The Evolution Trilogy by Vanessa Webster whilst stirring the Wizard's Cauldron

The Wizard speaks

WARNING - This is an EXCLUSIVE!!!! "It has only had one edit and the book is nowhere near completion yet… "

Read the extract and more about Vanessa at:

http://greenwizard62.blogspot.co.uk/2014/07/evolution-trilogy-author-vanessa-wester.html

Published on July 22, 2014 15:31

Diane Turner - London Rocks - 19.07.2014

Published on July 22, 2014 14:18

History Trivia - King Edward I of England defeates William Wallace at Battle of Falkirk

July 22

259 Dionysius was elected as bishop of Rome, succeeding Sixtus II.

838 Battle of Anzen: the Byzantine emperor Theophilos suffered a heavy defeat by the Abbasid Caliphate.

1099 First Crusade: Godfrey of Bouillon was elected the first Defender of the Holy Sepulchre of The Kingdom of Jerusalem.

1298 Wars of Scottish Independence: Battle of Falkirk – King Edward I of England and his longbowmen defeated William Wallace and his Scottish schiltrons outside the town of Falkirk.

1484 Battle of Lochmaben Fair A 500-man raiding party led by Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany and James Douglas, 9th Earl of Douglas were defeated by Scots forces loyal to Albany's brother James III of Scotland; Douglas was captured.

259 Dionysius was elected as bishop of Rome, succeeding Sixtus II.

838 Battle of Anzen: the Byzantine emperor Theophilos suffered a heavy defeat by the Abbasid Caliphate.

1099 First Crusade: Godfrey of Bouillon was elected the first Defender of the Holy Sepulchre of The Kingdom of Jerusalem.

1298 Wars of Scottish Independence: Battle of Falkirk – King Edward I of England and his longbowmen defeated William Wallace and his Scottish schiltrons outside the town of Falkirk.

1484 Battle of Lochmaben Fair A 500-man raiding party led by Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany and James Douglas, 9th Earl of Douglas were defeated by Scots forces loyal to Albany's brother James III of Scotland; Douglas was captured.

Published on July 22, 2014 08:01

July 21, 2014

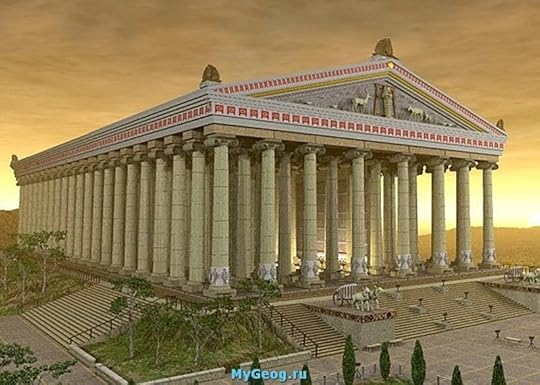

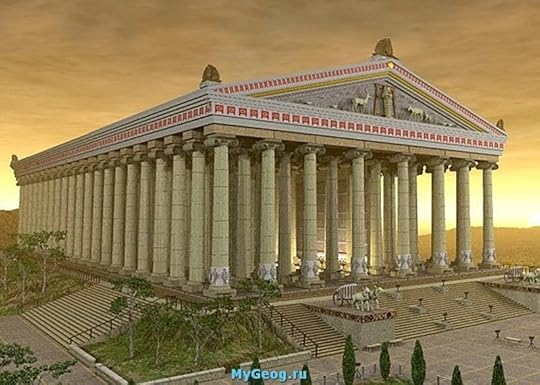

History Trivia - The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus destroyed by arson

July 21

356 BC The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, was destroyed by arson.

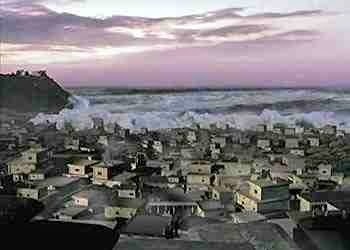

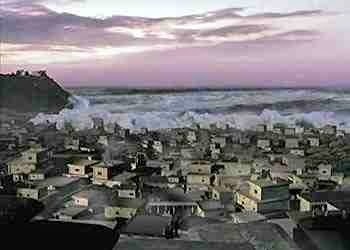

365 A tsunami devastated the city of Alexandria, Egypt. The tsunami was caused by an earthquake estimated to be 8.0 on the Richter Scale. 5,000 people perished in Alexandria, and 45,000 more died outside the city.

1403 Battle of Shrewsbury: King Henry IV of England defeated rebels to the north of the county town of Shropshire, England.

1545 The first landing of French troops on the coast of the Isle of Wight during the French invasion of the Isle of Wight.

1588 The Armada - an invasion fleet sent by Philip II of Spain - was sighted off the coast of Cornwall.

356 BC The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, was destroyed by arson.

365 A tsunami devastated the city of Alexandria, Egypt. The tsunami was caused by an earthquake estimated to be 8.0 on the Richter Scale. 5,000 people perished in Alexandria, and 45,000 more died outside the city.

1403 Battle of Shrewsbury: King Henry IV of England defeated rebels to the north of the county town of Shropshire, England.

1545 The first landing of French troops on the coast of the Isle of Wight during the French invasion of the Isle of Wight.

1588 The Armada - an invasion fleet sent by Philip II of Spain - was sighted off the coast of Cornwall.

Published on July 21, 2014 03:51

July 20, 2014

History Trivia - Norse nobleman Rollo captures and burns Chartres.

July 20

356 BC Alexander the Great was born.

70 First Jewish-Roman War: Siege of Jerusalem -Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, stormed the Fortress of Antonia north of the Temple Mount. The Roman army was drawn into street fights with the Zealots.

911 Norman incursions: Norse nobleman Rollo captured and burnt Chartres.

1304 Wars of Scottish Independence: Fall of Stirling Castle – King Edward I of England took the stronghold using the WarWolf (siege engine).

1304 Petrarch (Francisco Petracco) the Italian poet, scholar, and humanist was born.

1398 Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, heir to the throne of England died.

1553 British Government leader John Dudley was captured in Cambridge and later executed for treason for his part in putting Lady Jane Grey on the throne after the death of King Edward VI.

356 BC Alexander the Great was born.

70 First Jewish-Roman War: Siege of Jerusalem -Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian, stormed the Fortress of Antonia north of the Temple Mount. The Roman army was drawn into street fights with the Zealots.

911 Norman incursions: Norse nobleman Rollo captured and burnt Chartres.

1304 Wars of Scottish Independence: Fall of Stirling Castle – King Edward I of England took the stronghold using the WarWolf (siege engine).

1304 Petrarch (Francisco Petracco) the Italian poet, scholar, and humanist was born.

1398 Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, heir to the throne of England died.

1553 British Government leader John Dudley was captured in Cambridge and later executed for treason for his part in putting Lady Jane Grey on the throne after the death of King Edward VI.

Published on July 20, 2014 04:47