MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 239

September 12, 2014

3,000-Year-Old Golden Bowl Hides a Grisly Archaeological Tale

By Megan Gannon

The flattened golden bowl found at Hasanlu in 1958.

Credit: Antiquity Publications Ltd.

In 1958, archaeologists were digging through the ruins of a burned Iron Age citadel called Hasanlu in northwestern Iran when they pulled a spectacular, albeit crushed, golden bowl from the layers of destruction.

The 3,000-year-old bowl became an object of fascination once word got to the press. The next year, it graced the pages of Life magazine in a full-color spread alongside an article about the discoveries at Hasanlu.

But the story behind the prized find is less glossy. The bowl was uncovered just beyond the fingertips of a dead soldier and two of his comrades, who were crushed under bricks and burned building material around 800 B.C. Scholars have debated whether these three men were defenders of the citadel or enemy invaders running off with looted treasures. A new interpretation suggests the soldiers were no heroes.

Hasanlu is sometimes described as the Pompeii of the ancient Near East, because of its so-called "burn layer," which contains more than 200 bodies preserved in ash and rubble, explained Michael Danti, an archaeologist at Boston University. The archaeological evidence provides a rather disturbing snapshot of the closing hours of the siege of the citadel. [Preserved Pompeii: See Images of a City in Ash]

Located on the shores of Lake Urmia, Hasanlu seems to have been first occupied about 8,000 years ago. But by the ninth or 10th century B.C., there was a bustling, fortified town at the site.

Within the town's walls were houses, treasuries, horse stables, military arsenals and temples, many of which had towers or multiple stories. The mudbrick architecture likely resembled the adobe buildings of the American Southwest, but many roofs, floors and structural supports at Hasanlu consisted of timber and reed matting — all of which would have been tinder in a blaze, Danti said.

Other central details about life at Hasanlu are less clear. Archaeologists don't know the ethnicity of the people who lived there or what language they spoke.

"Despite the really rich material record, they didn't really find any indigenous writing at all," Danti said.

The burn layer at Hasanlu suggests a surprise attack destroyed the citadel. Archaeologists who excavated the site in the 1950s, '60s and '70s found corpses that were beheaded and others that were missing hands. Danti said he has seen a fairly clear example of a person who was cut in half. [8 Other Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

"The students that were working there would have nightmares at night, because they were spending hours and hours out there excavating murder victims," Danti told Live Science. Many of the victims were women and children. And in mass graves on top of the burned layer, excavators found the remains of people who tended to be very young or old and seemed to have suffered fatal, blunt-force trauma head wounds. These victims likely survived the initial attack only to be killed when their captors realized they would be of little use as slaves, Danti said.

"This was warfare that was designed to wipe out people's identity and terrify people into submission," Danti said.

Danti, who has been piecing together a history of the site from excavation archives as part of a larger, more daunting project, published a study on Hasanlu in the September 2014 issue of the journal Antiquity. The site was primarily excavated between 1956 and 1977 under the direction of Robert H. Dyson, who led a team from the University of Pennsylvania, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Archaeological Service of Iran. Because of security pressures and the overwhelming amount of material found at the site, the pace of their work was often hurried, and their record-keeping methods were not always meticulous. Some artifacts were pulled from the ground before they were documented or photographed in situ. There are no photographs of the gold bowl before it was taken out of the ground, for example.

In revisiting Hasanlu, Danti has taken a closer look at the three warriors. He said it seems likely they were climbing up a wooden staircase inside of a home when the building collapsed. The men fell through what was probably a waste-disposal chute and were buried by debris. Besides the gold bowl, there are other treasures scattered around their bodies, including textiles, fancy armored belts, metal vessels and delicately carved cylinder seals.

The outfits and weapons of the warriors look like standardized military equipment, Danti said. The men wore crested helmets with earflaps, and they carried spiked maces. They appear to have been well-prepared for battle.

"I doubt these men were rescuing a valued bowl and many other fine objects with little hope of egress as the citadel burned and its remaining occupants were slaughtered or taken captive," Danti wrote in his conclusion.

Danti's interpretation supports a hypothesis that the warriors hailed from the Urartu kingdom that grew out of an area in modern-day Turkey. Historical texts indicate the ancient Urartu kingdom was expanding into the region around Hasanlu during the Iron Age through a brutal military campaign. Sometime after the citadel was abandoned, an Urartian fortification wall was built on top of the ruins of Hasanlu.

Still, Danti said he hopes other researchers will test his hypothesis and perform bioarchaeological analyses on the skeletons of both the warriors and the slain people who lived at Hasanlu. Diet and drinking water leave telltale biomarkers in a person's skeleton, and a bone analysis could help confirm where the warriors came from, and whether they died trying to protect or steal the town's riches.

Live Science

The flattened golden bowl found at Hasanlu in 1958.

Credit: Antiquity Publications Ltd.

In 1958, archaeologists were digging through the ruins of a burned Iron Age citadel called Hasanlu in northwestern Iran when they pulled a spectacular, albeit crushed, golden bowl from the layers of destruction.

The 3,000-year-old bowl became an object of fascination once word got to the press. The next year, it graced the pages of Life magazine in a full-color spread alongside an article about the discoveries at Hasanlu.

But the story behind the prized find is less glossy. The bowl was uncovered just beyond the fingertips of a dead soldier and two of his comrades, who were crushed under bricks and burned building material around 800 B.C. Scholars have debated whether these three men were defenders of the citadel or enemy invaders running off with looted treasures. A new interpretation suggests the soldiers were no heroes.

Hasanlu is sometimes described as the Pompeii of the ancient Near East, because of its so-called "burn layer," which contains more than 200 bodies preserved in ash and rubble, explained Michael Danti, an archaeologist at Boston University. The archaeological evidence provides a rather disturbing snapshot of the closing hours of the siege of the citadel. [Preserved Pompeii: See Images of a City in Ash]

Located on the shores of Lake Urmia, Hasanlu seems to have been first occupied about 8,000 years ago. But by the ninth or 10th century B.C., there was a bustling, fortified town at the site.

Within the town's walls were houses, treasuries, horse stables, military arsenals and temples, many of which had towers or multiple stories. The mudbrick architecture likely resembled the adobe buildings of the American Southwest, but many roofs, floors and structural supports at Hasanlu consisted of timber and reed matting — all of which would have been tinder in a blaze, Danti said.

Other central details about life at Hasanlu are less clear. Archaeologists don't know the ethnicity of the people who lived there or what language they spoke.

"Despite the really rich material record, they didn't really find any indigenous writing at all," Danti said.

The burn layer at Hasanlu suggests a surprise attack destroyed the citadel. Archaeologists who excavated the site in the 1950s, '60s and '70s found corpses that were beheaded and others that were missing hands. Danti said he has seen a fairly clear example of a person who was cut in half. [8 Other Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

"The students that were working there would have nightmares at night, because they were spending hours and hours out there excavating murder victims," Danti told Live Science. Many of the victims were women and children. And in mass graves on top of the burned layer, excavators found the remains of people who tended to be very young or old and seemed to have suffered fatal, blunt-force trauma head wounds. These victims likely survived the initial attack only to be killed when their captors realized they would be of little use as slaves, Danti said.

"This was warfare that was designed to wipe out people's identity and terrify people into submission," Danti said.

Danti, who has been piecing together a history of the site from excavation archives as part of a larger, more daunting project, published a study on Hasanlu in the September 2014 issue of the journal Antiquity. The site was primarily excavated between 1956 and 1977 under the direction of Robert H. Dyson, who led a team from the University of Pennsylvania, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Archaeological Service of Iran. Because of security pressures and the overwhelming amount of material found at the site, the pace of their work was often hurried, and their record-keeping methods were not always meticulous. Some artifacts were pulled from the ground before they were documented or photographed in situ. There are no photographs of the gold bowl before it was taken out of the ground, for example.

In revisiting Hasanlu, Danti has taken a closer look at the three warriors. He said it seems likely they were climbing up a wooden staircase inside of a home when the building collapsed. The men fell through what was probably a waste-disposal chute and were buried by debris. Besides the gold bowl, there are other treasures scattered around their bodies, including textiles, fancy armored belts, metal vessels and delicately carved cylinder seals.

The outfits and weapons of the warriors look like standardized military equipment, Danti said. The men wore crested helmets with earflaps, and they carried spiked maces. They appear to have been well-prepared for battle.

"I doubt these men were rescuing a valued bowl and many other fine objects with little hope of egress as the citadel burned and its remaining occupants were slaughtered or taken captive," Danti wrote in his conclusion.

Danti's interpretation supports a hypothesis that the warriors hailed from the Urartu kingdom that grew out of an area in modern-day Turkey. Historical texts indicate the ancient Urartu kingdom was expanding into the region around Hasanlu during the Iron Age through a brutal military campaign. Sometime after the citadel was abandoned, an Urartian fortification wall was built on top of the ruins of Hasanlu.

Still, Danti said he hopes other researchers will test his hypothesis and perform bioarchaeological analyses on the skeletons of both the warriors and the slain people who lived at Hasanlu. Diet and drinking water leave telltale biomarkers in a person's skeleton, and a bone analysis could help confirm where the warriors came from, and whether they died trying to protect or steal the town's riches.

Live Science

Published on September 12, 2014 15:30

Hidden Monuments Reveal 'Stonehenge Is Not Alone'

By Megan Gannon

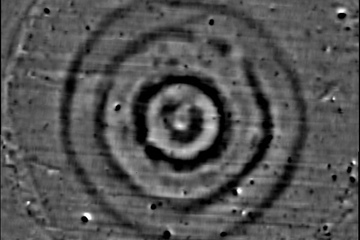

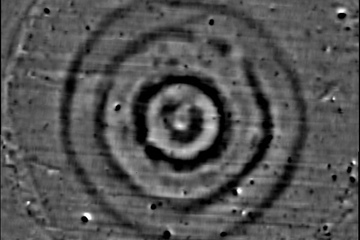

Data obtained from magnetometer surveys revealed impressions left by prehistoric monuments around Stonehenge. Some of the smaller monuments, researchers found, had a concentric circle design similar to Stonehenge.

Credit: © LBI ArchPro, Mario Wallner

The megaliths of Stonehenge, which were raised above England's Salisbury Plain some 5,000 years ago, may be among the most extensively studied archaeological features in the world. Still, the monument is keeping secrets.

Scientists have just unveiled the results of a four-year survey of the landscape around Stonehenge. Using non-invasive techniques like ground-penetrating radar, the researchers detected signs of at least 17 previously unknown Neolithic shrines.

"Stonehenge is undoubtedly a major ritual monument, which people may have traveled considerable distances to come to, but it isn't just standing there by itself," project leader Vincent Gaffney, an archaeologist at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., told Live Science. "It's part of a much more complex landscape with processional and ritual activities that go around it. That's very different from how this has been viewed before. The important point is Stonehenge is not alone. There was lots of other associated ritual activity going on around it." [See Images of Hidden Stonehenge Monuments]

Scholars still aren't sure why Stonehenge was built, as the monument's Neolithic creators left behind no written records. But the ruins, which align with the sun during the solstices, stand as an impressive feat of prehistoric engineering. The biggest stones at the site, known as sarsens, are up to 30 feet (9 meters) tall and weigh 25 tons (22.6 metric tons); they are believed to have been dragged from Marlborough Downs, 20 miles (32 kilometers) to the north.

[image error] The red circles mark the spots where archaeologists found satellite shrines around Stonehenge.

Credit: © LBI ArchPro, Wolfgang Neubauer

View full size imageAt the newfound satellite shrines around Stonehenge, Gaffney and his team revealed underground impressions, presumably left by wooden post holes, stones and ditches — some of which extend up to 13 feet (4 m) deep. Images created with geophysical prospecting tools show that some of these smaller monuments had a concentric circle design, much like Stonehenge.

The researchers also peered inside the Cursus, an immense prehistoric enclosure to the north of Stonehenge that dates back to about 3500 B.C. Stretching about 1.8 miles (3 km) long and 330 feet (100 m) wide, the Cursus had been deemed a barrier to Stonehenge, but it was so big that no one really knew what was inside of it, said Gaffney.

When the researchers surveyed this area, they found a large pit buried on the eastern end of the Cursus. This pit was aligned with Stonehenge's "avenue," a processional path that lines up with the sun at dawn during the mid-summer solstice. The team also found a matching pit at the other end of the Cursus. This pit is aligned with the Heel Stone at the entrance to Stonehenge, which is aligned with sunset during the solstice, Gaffney said.

"Suddenly, you've got a link between this very large monument and Stonehenge through two massive pits, which appear to be aligned on the sunrise and sunset on the mid-summer solstice," Gaffney said.

The researchers also mapped dozens of burial mounds in the area, including a long barrow that dates back to an era before Stonehenge. The team detected a timber building buried inside the mound, and the project leaders think this structure might have been used for the ritual inhumation and defleshing of the dead.

Gaffney said it will take his team about a year just to process all the data they collected during their 120 days of fieldwork over the span of four years. And then it will likely be up to English Heritage (the government body in charge of archaeological and historic sites) to decide which features to dig up in a more traditional excavation. Further study should help reveal the ages of these monuments, pits and burial mounds, and help explain how Stonehenge evolved over time.

The findings were revealed as part of the British Science Festival and will be featured in a new BBC Two series, "Operation Stonehenge: What Lies Beneath," which will air in the U.K. Thursday (Sept. 11) at 8 p.m. BST. A U.S. version of the special, dubbed "Stonehenge Empire," will air on the Smithsonian Channel Sept. 21 at 8 p.m. ET/PT. The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project is led by the University of Birmingham with the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology.

Live Science

Data obtained from magnetometer surveys revealed impressions left by prehistoric monuments around Stonehenge. Some of the smaller monuments, researchers found, had a concentric circle design similar to Stonehenge.

Credit: © LBI ArchPro, Mario Wallner

The megaliths of Stonehenge, which were raised above England's Salisbury Plain some 5,000 years ago, may be among the most extensively studied archaeological features in the world. Still, the monument is keeping secrets.

Scientists have just unveiled the results of a four-year survey of the landscape around Stonehenge. Using non-invasive techniques like ground-penetrating radar, the researchers detected signs of at least 17 previously unknown Neolithic shrines.

"Stonehenge is undoubtedly a major ritual monument, which people may have traveled considerable distances to come to, but it isn't just standing there by itself," project leader Vincent Gaffney, an archaeologist at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., told Live Science. "It's part of a much more complex landscape with processional and ritual activities that go around it. That's very different from how this has been viewed before. The important point is Stonehenge is not alone. There was lots of other associated ritual activity going on around it." [See Images of Hidden Stonehenge Monuments]

Scholars still aren't sure why Stonehenge was built, as the monument's Neolithic creators left behind no written records. But the ruins, which align with the sun during the solstices, stand as an impressive feat of prehistoric engineering. The biggest stones at the site, known as sarsens, are up to 30 feet (9 meters) tall and weigh 25 tons (22.6 metric tons); they are believed to have been dragged from Marlborough Downs, 20 miles (32 kilometers) to the north.

[image error] The red circles mark the spots where archaeologists found satellite shrines around Stonehenge.

Credit: © LBI ArchPro, Wolfgang Neubauer

View full size imageAt the newfound satellite shrines around Stonehenge, Gaffney and his team revealed underground impressions, presumably left by wooden post holes, stones and ditches — some of which extend up to 13 feet (4 m) deep. Images created with geophysical prospecting tools show that some of these smaller monuments had a concentric circle design, much like Stonehenge.

The researchers also peered inside the Cursus, an immense prehistoric enclosure to the north of Stonehenge that dates back to about 3500 B.C. Stretching about 1.8 miles (3 km) long and 330 feet (100 m) wide, the Cursus had been deemed a barrier to Stonehenge, but it was so big that no one really knew what was inside of it, said Gaffney.

When the researchers surveyed this area, they found a large pit buried on the eastern end of the Cursus. This pit was aligned with Stonehenge's "avenue," a processional path that lines up with the sun at dawn during the mid-summer solstice. The team also found a matching pit at the other end of the Cursus. This pit is aligned with the Heel Stone at the entrance to Stonehenge, which is aligned with sunset during the solstice, Gaffney said.

"Suddenly, you've got a link between this very large monument and Stonehenge through two massive pits, which appear to be aligned on the sunrise and sunset on the mid-summer solstice," Gaffney said.

The researchers also mapped dozens of burial mounds in the area, including a long barrow that dates back to an era before Stonehenge. The team detected a timber building buried inside the mound, and the project leaders think this structure might have been used for the ritual inhumation and defleshing of the dead.

Gaffney said it will take his team about a year just to process all the data they collected during their 120 days of fieldwork over the span of four years. And then it will likely be up to English Heritage (the government body in charge of archaeological and historic sites) to decide which features to dig up in a more traditional excavation. Further study should help reveal the ages of these monuments, pits and burial mounds, and help explain how Stonehenge evolved over time.

The findings were revealed as part of the British Science Festival and will be featured in a new BBC Two series, "Operation Stonehenge: What Lies Beneath," which will air in the U.K. Thursday (Sept. 11) at 8 p.m. BST. A U.S. version of the special, dubbed "Stonehenge Empire," will air on the Smithsonian Channel Sept. 21 at 8 p.m. ET/PT. The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project is led by the University of Birmingham with the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology.

Live Science

Published on September 12, 2014 15:25

Female Stone Statues Revealed in Ancient Greek Tomb

By Megan Gannon

A wall of sealing stones was removed to reveal the robe-covered bodies of two caryatids.

Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture

Archaeologists have uncovered the expertly crafted robes of two female stone statues standing guard at the entrance of a huge Macedonian tomb, dating back to the era of Alexander the Great, under excavation in Greece.

Excavators got their first glimpse of the wavy-haired statues — known as caryatids — last weekend, when the stone heads and torsos were unearthed at the ancient burial complex known as Kasta Hill in Amphipolis, 65 miles (104 kilometers) east of Thessaloniki. Archaeologists had to remove a wall of sealing stones to reveal the rest of the statues' bodies.

Anyone who has visited the Acropolis in Athens and stood in front of the Erechtheion would be familiar with caryatids, or female statues that take the place of columns or pillars. Though carved from stone, the diaphanous robes of the caryatids at Amphipolis have "exceptional" folds, officials with the Greek Ministry of Culture said in a statement yesterday (Sept. 11). [See Photos of the Alexander-Era Tomb Excavation]

The ongoing excavations at Amphipolis have been watched with excitement over the past several weeks. Two headless sphinxes were uncovered at the entrance of the huge burial mound, which is enclosed by a marble wall measuring some 1,600 feet (490 meters) in perimeter. Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras toured the site last month and hailed it as an "extremely important discovery."

As archaeologists venture deeper into the tomb, clearing sealing stones and sandy soil, they have revealed traces of paint and frescoes on the walls and door frames. The excavators have also found mosaics, some made with black and white pebbles arranged in a diamond pattern.

The discovery of the caryatids, partially covered by a sealing wall, suggests Kasta Hill is "an outstanding monument of particular importance," officials with the Greek Ministry of Culture said in a statement earlier this week.

"The right arm of the western caryatid and the left arm of the eastern one are both outstretched, as if to symbolically prevent anyone attempting to enter the grave," the statement added.

Katerina Peristeri, the lead archaeologist on the project, has said the team believes the tomb dates back to the fourth century B.C. and was built by Dinocrates, Alexander the Great's chief architect. The excavators have been tight-lipped about who they think might be buried inside. Some experts have speculated that the tomb might belong to one of Alexander's generals or immediate family members. But it likely won't contain the body of Alexander the Great himself — historical accounts indicate he was buried in Alexandria, though his remains have never been found.

Live Science

A wall of sealing stones was removed to reveal the robe-covered bodies of two caryatids.

Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture

Archaeologists have uncovered the expertly crafted robes of two female stone statues standing guard at the entrance of a huge Macedonian tomb, dating back to the era of Alexander the Great, under excavation in Greece.

Excavators got their first glimpse of the wavy-haired statues — known as caryatids — last weekend, when the stone heads and torsos were unearthed at the ancient burial complex known as Kasta Hill in Amphipolis, 65 miles (104 kilometers) east of Thessaloniki. Archaeologists had to remove a wall of sealing stones to reveal the rest of the statues' bodies.

Anyone who has visited the Acropolis in Athens and stood in front of the Erechtheion would be familiar with caryatids, or female statues that take the place of columns or pillars. Though carved from stone, the diaphanous robes of the caryatids at Amphipolis have "exceptional" folds, officials with the Greek Ministry of Culture said in a statement yesterday (Sept. 11). [See Photos of the Alexander-Era Tomb Excavation]

The ongoing excavations at Amphipolis have been watched with excitement over the past several weeks. Two headless sphinxes were uncovered at the entrance of the huge burial mound, which is enclosed by a marble wall measuring some 1,600 feet (490 meters) in perimeter. Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras toured the site last month and hailed it as an "extremely important discovery."

As archaeologists venture deeper into the tomb, clearing sealing stones and sandy soil, they have revealed traces of paint and frescoes on the walls and door frames. The excavators have also found mosaics, some made with black and white pebbles arranged in a diamond pattern.

The discovery of the caryatids, partially covered by a sealing wall, suggests Kasta Hill is "an outstanding monument of particular importance," officials with the Greek Ministry of Culture said in a statement earlier this week.

"The right arm of the western caryatid and the left arm of the eastern one are both outstretched, as if to symbolically prevent anyone attempting to enter the grave," the statement added.

Katerina Peristeri, the lead archaeologist on the project, has said the team believes the tomb dates back to the fourth century B.C. and was built by Dinocrates, Alexander the Great's chief architect. The excavators have been tight-lipped about who they think might be buried inside. Some experts have speculated that the tomb might belong to one of Alexander's generals or immediate family members. But it likely won't contain the body of Alexander the Great himself — historical accounts indicate he was buried in Alexandria, though his remains have never been found.

Live Science

Published on September 12, 2014 15:18

Ancient Viking Fortress Reveals 'Fierce Warriors' Were Decent Architects

By Elizabeth Palermo

Researchers explore the Viking fortress, discovered on the Vallø estate, near Køge, Denmark.

Researchers explore the Viking fortress, discovered on the Vallø estate, near Køge, Denmark.

Credit: The Danish Castle Centre The Vikings weren't just a fierce band of warriors with cool headgear. A new archaeological discovery in Denmark suggests that these notorious fighters were also decent builders.

Archaeologists on the Danish island of Zealand recently discovered a Viking fortress that likely dates back to the 10th century A.D. It's the first time in 60 years that such a fortress has been unearthed in Denmark, the researchers said.

"The Vikings have a reputation as [fierce Norse warriors] and pirates. It comes as a surprise to many that they were also capable of building magnificent fortresses," Søren Sindbæk, a professor of medieval archeology at Aarhus University in Denmark, said in a statement. The discovery of the new fortress provides an opportunity for archaeologists to gain even more knowledge about Viking wars and conflicts, Sindbæk added. [Fierce Fighters: 7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

Prior to this latest discovery, three other Viking fortresses were discovered in Denmark. These structures, named Fyrkat, Aggersborg and Trelleborg, are known collectively as the "Trelleborg" fortresses.

"We recognize the 'Trelleborg' fortresses by the precise circular shape of the ramparts and by the four massive gates that are directed at the four corners of the compass," said Nanna Holm, curator of the Danish Castle Centre in Denmark, who helped identify the site of the newly unearthed fortress. "Our investigations show that the new fortress was perfectly circular and had sturdy timber along the front. We have so far examined two gates, and they agree exactly with the 'Trelleborg' plan."

The fortress, located south of the capital city of Copenhagen, is huge, Holm said. It spans nearly 476 feet (145 meters) across, longer than 1.5 football fields.

Archaeologists long suspected that a fourth Trelleborg fortress might exist on the island of Zealand, according to Sindbæk, who has studied these structures for years. And the site of Vallø, now part of the Zealand Region on the east coast of Zealand, is an ideal place for the Vikings to have built such a structure, Sindbæk said.

During the 10th century, Vallø marked the spot where two main roads met, Sindbæk said. It also overlooked the Køge river valley, which at that time was a navigable fjord and one of the best natural harbors on the island, Sindbæk added.

Suspecting a fortress might be buried beneath Vallø, the team of archaeologists used advanced laser and magnetic tools to determine the structure's exact location. The team included Helen Goodchild from the University of York, in the United Kingdom.

"By measuring small variation[s] in the Earth's magnetism, we can identify old pits or features without destroying anything," Sindbæk said. "In this way, we achieved an amazingly detailed 'ghost image' of the fortress in a few days. Then we knew exactly where we had to put in excavation trenches to get as much information as possible about the mysterious fortress."

Once the team had uncovered the hidden structure, Holm said the researchers noticed a telltale sign that the fortress they had suspected was indeed buried there: At the north end of the site, the team found massive, charred oak posts, which the archaeologists said they think were once gates that had been burned down. The team is using radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, to determine the precise age of the charred wood, an effort that could help archaeologists figure out exactly when the fortress was constructed.

"We are eager to establish if the castle will turn out to be from the time of King Harald Bluetooth, like the previously known fortresses, or perhaps a former king's work," said Holm. "If we can establish exactly when the fortress was built, we may be able to understand the historic events which the fortress was part of."

Live Science

Researchers explore the Viking fortress, discovered on the Vallø estate, near Køge, Denmark.

Researchers explore the Viking fortress, discovered on the Vallø estate, near Køge, Denmark.Credit: The Danish Castle Centre The Vikings weren't just a fierce band of warriors with cool headgear. A new archaeological discovery in Denmark suggests that these notorious fighters were also decent builders.

Archaeologists on the Danish island of Zealand recently discovered a Viking fortress that likely dates back to the 10th century A.D. It's the first time in 60 years that such a fortress has been unearthed in Denmark, the researchers said.

"The Vikings have a reputation as [fierce Norse warriors] and pirates. It comes as a surprise to many that they were also capable of building magnificent fortresses," Søren Sindbæk, a professor of medieval archeology at Aarhus University in Denmark, said in a statement. The discovery of the new fortress provides an opportunity for archaeologists to gain even more knowledge about Viking wars and conflicts, Sindbæk added. [Fierce Fighters: 7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

Prior to this latest discovery, three other Viking fortresses were discovered in Denmark. These structures, named Fyrkat, Aggersborg and Trelleborg, are known collectively as the "Trelleborg" fortresses.

"We recognize the 'Trelleborg' fortresses by the precise circular shape of the ramparts and by the four massive gates that are directed at the four corners of the compass," said Nanna Holm, curator of the Danish Castle Centre in Denmark, who helped identify the site of the newly unearthed fortress. "Our investigations show that the new fortress was perfectly circular and had sturdy timber along the front. We have so far examined two gates, and they agree exactly with the 'Trelleborg' plan."

The fortress, located south of the capital city of Copenhagen, is huge, Holm said. It spans nearly 476 feet (145 meters) across, longer than 1.5 football fields.

Archaeologists long suspected that a fourth Trelleborg fortress might exist on the island of Zealand, according to Sindbæk, who has studied these structures for years. And the site of Vallø, now part of the Zealand Region on the east coast of Zealand, is an ideal place for the Vikings to have built such a structure, Sindbæk said.

During the 10th century, Vallø marked the spot where two main roads met, Sindbæk said. It also overlooked the Køge river valley, which at that time was a navigable fjord and one of the best natural harbors on the island, Sindbæk added.

Suspecting a fortress might be buried beneath Vallø, the team of archaeologists used advanced laser and magnetic tools to determine the structure's exact location. The team included Helen Goodchild from the University of York, in the United Kingdom.

"By measuring small variation[s] in the Earth's magnetism, we can identify old pits or features without destroying anything," Sindbæk said. "In this way, we achieved an amazingly detailed 'ghost image' of the fortress in a few days. Then we knew exactly where we had to put in excavation trenches to get as much information as possible about the mysterious fortress."

Once the team had uncovered the hidden structure, Holm said the researchers noticed a telltale sign that the fortress they had suspected was indeed buried there: At the north end of the site, the team found massive, charred oak posts, which the archaeologists said they think were once gates that had been burned down. The team is using radiocarbon dating and dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, to determine the precise age of the charred wood, an effort that could help archaeologists figure out exactly when the fortress was constructed.

"We are eager to establish if the castle will turn out to be from the time of King Harald Bluetooth, like the previously known fortresses, or perhaps a former king's work," said Holm. "If we can establish exactly when the fortress was built, we may be able to understand the historic events which the fortress was part of."

Live Science

Published on September 12, 2014 15:12

Armor Made of Bones Found in Bronze Age Grave

by Rossella Lorenzi

Archaeologists in Siberia have unearthed Bronze Age armor crafted from bones in an outfit that George R.R. Martin's epic fantasy character "Rattleshirt" might have worn.

Dating to between 3,900 and 3,500 years old, the armor was buried without its owner at a depth of 5 feet near the Irtysh River in Omsk. Analysis is underway to determine what kind of animal bones were used for the protective outfit, but it was likely assembled with bones from elk, deer and horse.

A reconstruction of the Bronze Age bone armor. Polina Volf, Yuri Gerasimov, A.Solovyev-The Siberian Times "At the moment we can only fantasize — who dug it into the ground and for what purpose. Was it some ritual or sacrifice? We do not know yet," Yury Gerasimov of the Omsk branch of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography told The Siberian Times.

A reconstruction of the Bronze Age bone armor. Polina Volf, Yuri Gerasimov, A.Solovyev-The Siberian Times "At the moment we can only fantasize — who dug it into the ground and for what purpose. Was it some ritual or sacrifice? We do not know yet," Yury Gerasimov of the Omsk branch of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography told The Siberian Times.

Laminated Linen Protected Alexander the Great

He believes it's possible the site was a place of worship.

"Armor had great material value. There was no sense to dig it in the ground or hide it for a long time — because the fixings and the bones would be ruined," Gerasimov said.

The archaeological site is known for findings dating from the Early Neolithic to the Middle Ages.

During the Bronze Age, the region was inhabited by animal breeder members of the Krotov culture.

The armor, however, resembles artifacts from the Samus-Seyminskaya culture, whose members originated in the Altai Mountain, about 620 miles to the south east, and who later migrated to Omsk.

Bronze-Age Battle Frozen in Time

If this is the case, the bone outfit could have been a gift, an item obtained through trade, or a spoil of war.

Most likely it belonged to an elite warrior and would have offered protection from Bronze Age weapons such as bone and stone arrowheads, bronze knives, spears tipped with bronze, and bronze axes.

"It was more precious than life, because it saved life," Boris Konikov, curator of the excavations, said.

Video: Mythical Viking Sunstone is Real

The fragile armor is now undergoing restoration. Fragments of bone plates are carefully extracted from blocks of soil in the lab; once cleaned, they will be glued in a full plate.

"It's a long, painstaking process. As a result we hope to reconstruct an exact copy of the armor," Konikov said.

Image: The Bronze Age bone armor. Credit: The Siberan Times.

Discovery News

Archaeologists in Siberia have unearthed Bronze Age armor crafted from bones in an outfit that George R.R. Martin's epic fantasy character "Rattleshirt" might have worn.

Dating to between 3,900 and 3,500 years old, the armor was buried without its owner at a depth of 5 feet near the Irtysh River in Omsk. Analysis is underway to determine what kind of animal bones were used for the protective outfit, but it was likely assembled with bones from elk, deer and horse.

A reconstruction of the Bronze Age bone armor. Polina Volf, Yuri Gerasimov, A.Solovyev-The Siberian Times "At the moment we can only fantasize — who dug it into the ground and for what purpose. Was it some ritual or sacrifice? We do not know yet," Yury Gerasimov of the Omsk branch of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography told The Siberian Times.

A reconstruction of the Bronze Age bone armor. Polina Volf, Yuri Gerasimov, A.Solovyev-The Siberian Times "At the moment we can only fantasize — who dug it into the ground and for what purpose. Was it some ritual or sacrifice? We do not know yet," Yury Gerasimov of the Omsk branch of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography told The Siberian Times.Laminated Linen Protected Alexander the Great

He believes it's possible the site was a place of worship.

"Armor had great material value. There was no sense to dig it in the ground or hide it for a long time — because the fixings and the bones would be ruined," Gerasimov said.

The archaeological site is known for findings dating from the Early Neolithic to the Middle Ages.

During the Bronze Age, the region was inhabited by animal breeder members of the Krotov culture.

The armor, however, resembles artifacts from the Samus-Seyminskaya culture, whose members originated in the Altai Mountain, about 620 miles to the south east, and who later migrated to Omsk.

Bronze-Age Battle Frozen in Time

If this is the case, the bone outfit could have been a gift, an item obtained through trade, or a spoil of war.

Most likely it belonged to an elite warrior and would have offered protection from Bronze Age weapons such as bone and stone arrowheads, bronze knives, spears tipped with bronze, and bronze axes.

"It was more precious than life, because it saved life," Boris Konikov, curator of the excavations, said.

Video: Mythical Viking Sunstone is Real

The fragile armor is now undergoing restoration. Fragments of bone plates are carefully extracted from blocks of soil in the lab; once cleaned, they will be glued in a full plate.

"It's a long, painstaking process. As a result we hope to reconstruct an exact copy of the armor," Konikov said.

Image: The Bronze Age bone armor. Credit: The Siberan Times.

Discovery News

Published on September 12, 2014 15:04

Egyptian heritage group raises concerns over Djoser pyramid restorations

Patrick Kingsley

Outside of pyramid looks very different to how it should, and structure may have suffered internal damage, archaeologists say

The Djoser Pyramid in Cairo, Egypt after conservation and restoration works. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task ForceEgypt's oldest pyramid may have been ruined by conservators, a group of heritage campaigners has warned.

The Djoser Pyramid in Cairo, Egypt after conservation and restoration works. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task ForceEgypt's oldest pyramid may have been ruined by conservators, a group of heritage campaigners has warned.

The step-shaped pyramid of Djoser, a few miles south of the better-known pyramids of Giza, is more than 4,600 years old and is considered the oldest stone structure of its size in the world.

After a decade of restoration attempts, the outside of the pyramid now looks very different to how it should, and the structure may also have suffered internal damage, according to Egypt's Heritage Task Force (EHTF), an archaeological pressure group.

Egypt's antiquities minister, Mamdouh el-Damaty, denies the allegations. EHTF has called for an international inquiry led by Unesco and Iccrom – a champion of global restoration efforts – to determine whether the claims have merit.

"The problem is a very bad procedure of conservation," said Monica Hanna, a spokesman for the taskforce. "If you compare images of the pyramid from 10 years ago, it looks very different. The colour and texture is very different."

Recent photographs confirm that the base of the pyramid has been given a jarring contemporary appearance, and now looks markedly smoother and lighter than it did a decade ago.

A closer up view of the Pyramid base. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task Force As archaeologists rather than conservators, EHTF admit they cannot themselves judge the quality of the external work, nor the allegations of internal collapse. But they want an independent panel of Egyptian and international restorers "to tell us if the work was good or bad and how we can save the pyramid", says Hanna.

A closer up view of the Pyramid base. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task Force As archaeologists rather than conservators, EHTF admit they cannot themselves judge the quality of the external work, nor the allegations of internal collapse. But they want an independent panel of Egyptian and international restorers "to tell us if the work was good or bad and how we can save the pyramid", says Hanna.

Damaty has said the restoration is of the highest quality, and says attempts to suggest otherwise originate from supporters of the ousted president Mohamed Morsi. "There is nothing wrong, the company is doing a very professional job," Damaty said this week. "I went to the place which they said was collapsing. I went 28 metres down and I came out again without any rock falling on me."

Campaigners argue that the construction company commissioned to restore the pyramid, el-Shorbagy, is too inexperienced to be involved in the project – allegations that led to the project's suspension two years ago.

El-Shorbagy could not be reached by telephone for comment. Damaty said the company had been given the all-clear by his deputies, and could restart work again. "The manager of the antiquities sector went to see what was going on, and after checking the operations at the pyramids he declared that the restoration was one of the best in the world," he said.

The Guardian

Outside of pyramid looks very different to how it should, and structure may have suffered internal damage, archaeologists say

The Djoser Pyramid in Cairo, Egypt after conservation and restoration works. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task ForceEgypt's oldest pyramid may have been ruined by conservators, a group of heritage campaigners has warned.

The Djoser Pyramid in Cairo, Egypt after conservation and restoration works. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task ForceEgypt's oldest pyramid may have been ruined by conservators, a group of heritage campaigners has warned.The step-shaped pyramid of Djoser, a few miles south of the better-known pyramids of Giza, is more than 4,600 years old and is considered the oldest stone structure of its size in the world.

After a decade of restoration attempts, the outside of the pyramid now looks very different to how it should, and the structure may also have suffered internal damage, according to Egypt's Heritage Task Force (EHTF), an archaeological pressure group.

Egypt's antiquities minister, Mamdouh el-Damaty, denies the allegations. EHTF has called for an international inquiry led by Unesco and Iccrom – a champion of global restoration efforts – to determine whether the claims have merit.

"The problem is a very bad procedure of conservation," said Monica Hanna, a spokesman for the taskforce. "If you compare images of the pyramid from 10 years ago, it looks very different. The colour and texture is very different."

Recent photographs confirm that the base of the pyramid has been given a jarring contemporary appearance, and now looks markedly smoother and lighter than it did a decade ago.

A closer up view of the Pyramid base. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task Force As archaeologists rather than conservators, EHTF admit they cannot themselves judge the quality of the external work, nor the allegations of internal collapse. But they want an independent panel of Egyptian and international restorers "to tell us if the work was good or bad and how we can save the pyramid", says Hanna.

A closer up view of the Pyramid base. Photograph: Egypt's Heritage Task Force As archaeologists rather than conservators, EHTF admit they cannot themselves judge the quality of the external work, nor the allegations of internal collapse. But they want an independent panel of Egyptian and international restorers "to tell us if the work was good or bad and how we can save the pyramid", says Hanna.Damaty has said the restoration is of the highest quality, and says attempts to suggest otherwise originate from supporters of the ousted president Mohamed Morsi. "There is nothing wrong, the company is doing a very professional job," Damaty said this week. "I went to the place which they said was collapsing. I went 28 metres down and I came out again without any rock falling on me."

Campaigners argue that the construction company commissioned to restore the pyramid, el-Shorbagy, is too inexperienced to be involved in the project – allegations that led to the project's suspension two years ago.

El-Shorbagy could not be reached by telephone for comment. Damaty said the company had been given the all-clear by his deputies, and could restart work again. "The manager of the antiquities sector went to see what was going on, and after checking the operations at the pyramids he declared that the restoration was one of the best in the world," he said.

The Guardian

Published on September 12, 2014 14:57

Stonehenge Was Actually Part of a Huge Ancient Complex, Researchers Discover

Sam Frizell

Sam FrizellBurial mounds, sun-aligned pits and ancient delights galoreFor a disenchanted visitor to Stonehenge in the south of England, the iconic array of 4,000-year-old pillars may have signified little more than a pile of rocks. But a new discovery that Stonehenge was actually the heart of a huge complex of ancient burial mounds and shrines could win over even the most cynical observer

Researchers at the University of Birmingham have found a host of previously unknown monuments, including ritual structures and a massive timber building that was likely used for burial of the dead during a complicated sequence of exposure and de-fleshing.

“New monuments have been revealed, as well as new types of monument that have previously never been seen by archaeologists,” Professor Vincent Gaffney, the project leader, said in a statement Wednesday. “Stonehenge may never be the same again.”

The project, which made use of remote sensing techniques and geophysical surveys, discovered large prehistoric pits, some of which are aligned with the sun, and new information on Bronze Age, Iron Age and Roman settlements and fields.

Stonehenge draws more than 1.2 million visitors a year, including President Barack Obama last week, the Associated Press reports.

Time Discovery

Published on September 12, 2014 09:41

My review of Shattered Reality by Brenda Perlin

Shattered Reality is a story about a woman named Brooklyn who was in a loveless marriage until a lift-altering experience leaves her contemplating her future. The author shares her childhood memories, the good and the bad, and the reasons why she married a man she did not really love. After surviving a debilitating illness, she meets by chance, Bo, who would eventually steal her heart. While the reader may not condone infidelity, it is not difficult to understand why Brooklyn made the decision to radically change her life. A heart-wrenching confession, honestly written.Amazon Purchase Link

Published on September 12, 2014 06:35

History Trivia - Simon de Montfort, 5th Earl of Leicester, defeats Peter II of Aragon at the Battle of Muret.

Sept 12

1185 Byzantine emperor Andronicus I was tortured and executed by the Greek nobility, led by Isaac Angelus, during a war between the Byzantines and Norman invaders of the empire.

1213 Albigensian Crusade (directed against Christian heretics in southern France) Simon de Montfort, 5th Earl of Leicester, defeated Peter II of Aragon at the Battle of Muret.

1362 Pope Innocent VI died. With a background in civil law, Innocent took an interest in reform and in the possibility of ending the Avignon Papacy.

1185 Byzantine emperor Andronicus I was tortured and executed by the Greek nobility, led by Isaac Angelus, during a war between the Byzantines and Norman invaders of the empire.

1213 Albigensian Crusade (directed against Christian heretics in southern France) Simon de Montfort, 5th Earl of Leicester, defeated Peter II of Aragon at the Battle of Muret.

1362 Pope Innocent VI died. With a background in civil law, Innocent took an interest in reform and in the possibility of ending the Avignon Papacy.

Published on September 12, 2014 06:34

September 11, 2014

Remembering September 11, 2001

Published on September 11, 2014 05:44